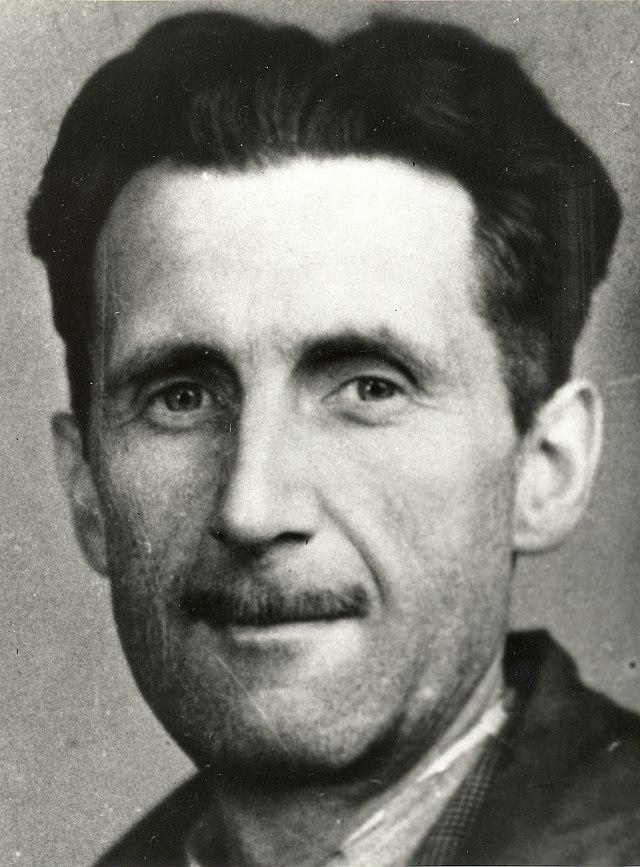

George Orwell (1903—1950)

Eric Arthur Blair, better known by his pen name George Orwell, was a British essayist, journalist, and novelist. Orwell is most famous for his dystopian works of fiction, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, but many of his essays and other books have remained popular as well. His body of work provides one of the twentieth century’s most trenchant and widely recognized critiques of totalitarianism.

Eric Arthur Blair, better known by his pen name George Orwell, was a British essayist, journalist, and novelist. Orwell is most famous for his dystopian works of fiction, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, but many of his essays and other books have remained popular as well. His body of work provides one of the twentieth century’s most trenchant and widely recognized critiques of totalitarianism.

Orwell did not receive academic training in philosophy, but his writing repeatedly focuses on philosophical topics and questions in political philosophy, epistemology, philosophy of language, ethics, and aesthetics. Some of Orwell’s most notable philosophical contributions include his discussions of nationalism, totalitarianism, socialism, propaganda, language, class status, work, poverty, imperialism, truth, history, and literature.

Orwell’s writings map onto his intellectual journey. His earlier writings focus on poverty, work, and money, among other themes. Orwell examines poverty and work not only from an economic perspective, but also socially, politically, and existentially, and he rejects moralistic and individualistic accounts of poverty in favor of systemic explanations. In so doing, he provides the groundwork for his later championing of socialism.

Orwell’s experiences in the 1930s, including reporting on the living conditions of the poor and working class in Northern England as well as fighting as a volunteer soldier in the Spanish Civil War, further crystalized Orwell’s political and philosophical outlook. This led him to write in 1946 that, “Every line of serious work I have written since 1936 has been, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism” (“Why I Write”).

For Orwell, totalitarianism is a political order focused on power and control. Much of Orwell’s effectiveness in writing against totalitarianism stems from his recognition of the epistemic and linguistic dimensions of totalitarianism. This is exemplified by Winston Smith’s claim as the protagonist in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two makes four. If that is granted, all else follows.” Here Orwell uses, as he often does, a particular claim to convey a broader message. Freedom (a political state) rests on the ability to retain the true belief that two plus two makes four (an epistemic state) and the ability to communicate that truth to others (via a linguistic act).

Orwell also argues that political power is dependent upon thought and language. This is why the totalitarian, who seeks complete power, requires control over thought and language. In this way, Orwell’s writing can be viewed as philosophically ahead of its time for the way it brings together political philosophy, epistemology, and philosophy of language.

Table of Contents

- Biography

- Political Philosophy

- Epistemology and Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Art and Literature

- Orwell’s Relationship to Academic Philosophy

- References and Further Reading

1. Biography

Eric Arthur Blair was born on June 25, 1903 in India. His English father worked as a member of the British specialized services in colonial India, where he oversaw local opium production for export to China. When Blair was less than a year old, his mother, of English and French descent, returned to England with him and his older sister. He saw relatively little of his father until he was eight years old.

Blair described his family as part of England’s “lower-upper-middle class.” Blair had a high degree of class consciousness, which became a common theme in his work and a central concern in his autobiographical essay, “Such, Such Were the Joys” (facetiously titled) about his time at the English preparatory school St. Cyprian’s, which he attended from ages eight to thirteen on a merit-based scholarship. After graduating from St. Cyprian’s, from ages thirteen to eighteen Orwell attended the prestigious English public school, Eton, also on a merit-based scholarship.

After graduating from Eton, where he had not been a particularly successful student, Blair decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and join the specialized services of the British Empire rather than pursue higher education. Blair was stationed in Burma (now Myanmar) where his mother had been raised. He spent five unhappy years with the Imperial Police in Burma (1922-1927) before leaving the position to return to England in hopes of becoming a writer.

Partly out of need and partly out of desire, Blair spent several years living in or near poverty both in Paris and London. His experiences formed the basis for his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London, which was published in 1933. Blair published the book under the pen name George Orwell, which became the moniker he would use for his published writings for the rest of his life.

Orwell’s writing was often inspired by personal experience. He used his experiences working for imperial Britain in Burma as the foundation for his second book, Burmese Days, first published in 1934, and his frequently anthologized essays, “A Hanging” and “Shooting an Elephant,” first published in 1931 and 1936 respectively.

He drew on his experiences as a hop picker and schoolteacher in his third novel, A Clergyman’s Daughter, first published in 1935. His next novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, published in 1936, featured a leading character who had given up a middle-class job for the subsistence pay of a book seller and the chance to try to make it as a writer. At the end of the novel, the protagonist gets married and returns to his old middle-class job. Orwell wrote this book while he himself was working as a book seller who would soon be married.

The years 1936-1937 included several major events for Orwell, which would influence his writing for the rest of his life. Orwell’s publisher, the socialist Victor Gollancz, suggested that Orwell spend time in the industrial north of England in order to gather experience about the conditions there for journalistic writing. Orwell did so during the winter of 1936. Those experiences formed the foundation for his 1937 book, The Road to Wigan Pier. The first half of Wigan Pier reported on the poor working conditions and poverty that Orwell witnessed. The second half focused on the need for socialism and the reasons why Orwell thought the British left intelligentsia had failed in convincing the poor and working class of the need for socialism. Gollancz published Wigan Pier as part of his Left Book Club, which provided Wigan Pier with a larger platform and better sales than any of his previous books.

In June 1936, Orwell married Eileen O’Shaughnessy, an Oxford graduate with a degree in English who had worked various jobs including those of teacher and secretary. Shortly thereafter, Orwell became a volunteer soldier fighting on behalf of the left-leaning Spanish Republicans against Francisco Franco and the Nationalist right in the Spanish Civil War. His wife joined him in Spain later. Orwell’s experiences in Spain further entrenched his shift towards overtly political writing. He experienced first-hand the infighting between various factions opposed to Franco on the political left. He also witnessed the control that the Soviet Communists sought to exercise over both the war, and perhaps more importantly, the narratives told about the war.

Orwell fought with the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista) militia that was later maligned by Soviet propaganda. The Soviets leveled a range of accusations against the militia, including that its members were Trotskyists and spies for the other side. As a result, Spain became an unsafe place for him and Eileen. They escaped Spain by train to France in the summer of 1937. Orwell later wrote about his experiences in the Spanish Civil War in Homage to Catalonia, published in 1938.

While Wigan Pier had signaled the shift to an abiding focus on politics and political ideas in Orwell’s writing, similarly, Homage to Catalonia signaled the shift to an abiding focus on epistemology and language in his work. Orwell’s time in Spain helped him understand how language shapes beliefs and how beliefs, in turn, shape the contours of power. Thus, Homage to Catalonia does not mark a mere epistemic and linguistic turn in Orwell’s thinking. It also marks a significant development in Orwell’s views about the complex relationship between language, thought, and power.

Orwell’s experiences in Spain also further cemented his anti-Communism and his role as a critic of the left operating within the left. After a period of ill health upon returning from Spain due to his weak lungs from having been shot in his throat during battle, Orwell took on a grueling pace of literary production, publishing Coming Up for Air in 1939, Inside the Whale and Other Essays in 1940, and his lengthy essay on British Socialism, “The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius” in 1941, as well as many other essays and reviews.

Orwell would have liked to have served in the military during the Second World War, but his ill health prevented him from doing so. Instead, between 1941-1943 he worked for the British Broadcasting Company (BBC). His job was meant, in theory, to aid Britain’s war efforts. Orwell was tasked with creating and delivering radio content to listeners on the Indian subcontinent in hopes of creating support for Britain and the Allied Powers. There were, however, relatively few listeners, and Orwell came to consider the job a waste of his time. Nevertheless, his experiences of bureaucracy and censorship at the BBC would later serve as one of the inspirations for the “Ministry of Truth,” which played a prominent role in the plot of Nineteen Eighty-Four (Sheldon 1991, 380-381).

Orwell’s final years were a series of highs and lows. After leaving the BBC, Orwell was hired as the literary editor at the democratic socialist magazine, the Tribune. As part of his duties, he wrote a regular column titled “As I Please.” He and Eileen, who herself was working for the BBC, adopted a baby boy named Richard in 1944. Shortly before they adopted Richard, Orwell had finished work on what was to be his breakthrough work, Animal Farm. Orwell originally had trouble finding someone to publish Animal Farm due to its anti-Communist message and publishers’ desires not to undermine Britain’s war effort, given that the United Kingdom was allied with the USSR against Nazi Germany at the time. The book was eventually published in August 1945, a few months after Eileen had died unexpectedly during an operation at age thirty-nine.

Animal Farm was a commercial success in both the United States and the United Kingdom. This gave Orwell both wealth and literary fame. Orwell moved with his sister Avril and Richard to the Scottish island of Jura, where Orwell hoped to be able to write with less interruption and to provide a good environment in which to raise Richard. During this time, living without electricity on the North Atlantic coast, Orwell’s health continued to decline. He was eventually diagnosed with tuberculosis.

Orwell pressed ahead on completing what was to be his last book, Nineteen Eighty-Four. In the words of one of Orwell’s biographers, Michael Sheldon, Nineteen Eighty-Four is a book in which “Almost every aspect of Orwell’s life is in some way represented.” Published in 1949, Nineteen Eighty-Four was in many ways the culmination of Orwell’s life work: it dealt with all the major themes from his writing—poverty, social class, war, totalitarianism, nationalism, censorship, truth, history, propaganda, language, and literature, among others.

Orwell died less than a year after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Shortly before his death, he had married Sonia Brownell, who had worked for the literary magazine Horizons. Brownell, who later went by Sonia Brownell Orwell, became one of Orwell’s literary executors. Her efforts to promote her late husband’s work included establishing the George Orwell Archive at University College London and co-editing with Ian Angus a four-volume collection of Orwell’s essays, journalism, and letters, first published in 1968. The publication of this collection further increased interest in Orwell and his work, which has yet to abate in the over seventy years since his death.

2. Political Philosophy

Orwell’s claim that “Every line of serious work I have written since 1936 has been, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism,” divides Orwell’s work into two parts: pre-1936 and 1936-and-after.

Orwell’s second period (1936-and-after) is characterized by his strong views on politics and his focus on the interconnections between language, thought, and power. Orwell’s first period (pre-1936) focuses on two sets of interrelated themes: (1) poverty, money, work, and social status, and (2) imperialism and its ethical costs.

a. Poverty, Money, and Work

Orwell frequently wrote about poverty. It is a central topic in his books Down and Out and Wigan Pier and many of his essays, including “The Spike” and “How the Poor Die.” In writing about poverty, Orwell does not adopt an objective “view from nowhere”: rather, he writes as a member of the middle class to readers in the upper and middle classes. In doing so, he seeks to correct common misconceptions about poverty held by those in the upper and middle classes. These correctives deal with both the phenomenology of poverty and its causes.

His overall picture of poverty is less dramatic but more benumbing than his audience might initially imagine: one’s spirit is not crushed by poverty but rather withers away underneath it.

Orwell’s phenomenology of poverty is exemplified in the following passage from Down and Out:

It is altogether curious, your first contact with poverty. You have thought so much about poverty it is the thing you have feared all your life, the thing you knew would happen to you sooner or later; and it, is all so utterly and prosaically different. You thought it would be quite simple; it is extraordinarily complicated. You thought it would be terrible; it is merely squalid and boring. It is the peculiar lowness of poverty that you discover first; the shifts that it puts you to, the complicated meanness, the crust-wiping (Down and Out, 16-17).

This account tracks Orwell’s own experiences by assuming the perspective of one who encounters poverty later in life, rather than the perspective of someone born into poverty. At least for those who “come down” into poverty, Orwell identifies a silver lining in poverty: that the fear of poverty in a hierarchical capitalist society is perhaps worse than poverty itself. Once you realize that you can survive poverty (which is something Orwell seemed to think most middle-class people in England who later become impoverished could), there is “a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out” (Down and Out, 20-21). This silver lining, however, seems to be limited to those who enter poverty after having received an education. Orwell concludes that those who have always been down and out are the ones who deserve pity because such a person “faces poverty with a blank, resourceless mind” (Down and Out, 180). This latter statement invokes controversial assumptions in the philosophy of mind and is indicative of the ways in which Orwell was never able to overcome certain class biases from his own education. Orwell’s views on the working class and the poor have been critiqued by some scholars, including Raymond Williams (1971) and Beatrix Campbell (1984).

Much of Orwell’s discussion about poverty is aimed at humanizing poor people and at rooting out misconceptions about poor people. Orwell saw no inherent difference of character between rich and poor. It was their circumstances that differed, not their moral goodness. He identifies the English as having a “a strong sense of the sinfulness of poverty” (Down and Out, 202). Through personal narratives, Orwell seeks to undermine this sense, concluding instead that “The mass of the rich and the poor are differentiated by their incomes and nothing else, and the average millionaire is only the average dishwasher dressed in a new suit” (Down and Out, 120). Orwell blames poverty instead on systemic factors, which the rich have the ability to change. Thus, if Orwell were to pass blame for the existence of poverty, it is not the poor on whom he would pass blame.

If poverty is erroneously associated with vice, Orwell notes that money is also erroneously associated with virtue. This theme is taken up most directly in his 1936 novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, which highlights the central role that money plays in English life through the failures of the novel’s protagonist to live a fulfilling life that does not revolve around money. Orwell is careful to note that the significance of money is not merely economic, but also social. In Wigan Pier, Orwell notes that English class stratification is a “money-stratification” but that it is also a “shadowy caste-system” that “is not entirely explicable in terms of money” (122). Thus, both money and culture seem to play a role in Orwell’s account of class stratification in England.

Orwell’s view on the social significance of money helped shape his views about socialism. For example, in “The Lion and the Unicorn,” Orwell argued in favor of a socialist society in which income disparities were limited on the grounds that a “man with £3 a week and a man with £1500 a year can feel themselves fellow creatures, which the Duke of Westminster and the sleepers on the Embankment benches cannot.”

Orwell was attuned to various ways in which money impacts work and vice versa. For example, in Keep the Aspidistra Flying, the protagonist, Gordon Comstock, leaves his job in order to have time to write, only to discover that the discomforts of living on very little money have drained him of the motivation and ability to write. This is in keeping with Orwell’s view that creative work, such as making art or writing stories, requires a certain level of financial comfort. Orwell expresses this view in Wigan Pier, writing that, “You can’t command the spirit of hope in which anything has got to be created, with that dull evil cloud of unemployment hanging over you” (82).

Orwell sees this inability to do creative or other meaningful work as itself one of the harmful consequences of poverty. This is because Orwell views engaging in satisfying work as a meaningful part of human experience. He argues that human beings need work and seek it out (Wigan Pier, 197) and even goes so far as to claim that being cut off from the chance to work is being cut off from the chance of living (Wigan Pier, 198). But this is because Orwell sees work as a way in which we can meaningfully engage both our bodies and our minds. For Orwell, work is valuable when it contributes to human flourishing.

But this does not mean that Orwell thinks all work has such value. Orwell is often critical of various social circumstances that require people to engage in work that they find degrading, menial, or boring. He shows particular distaste for working conditions that combine undesirability with inefficiency or exploitation, such as the conditions of low-level staff in Paris restaurants and coal miners in Northern England. Orwell recognizes that workers tolerate such conditions out of necessity and desperation, even though such working conditions often rob the workers of many aspects of a flourishing human life.

b. Imperialism and Oppression

By the time he left Burma at age 24, Orwell had come to strongly oppose imperialism. His anti-imperialist works include his novel Burmese Days, his essays “Shooting an Elephant” and “A Hanging,” and chapter 9 of Wigan Pier, in which he wrote that by the time he left his position with the Imperial Police in Burma that “I hated the imperialism I was serving with a bitterness which I probably cannot make clear” (Wigan Pier, 143).

In keeping with Orwell’s tendency to write from experience, Orwell focused mostly on the damage that he saw imperialism causing the imperialist oppressor rather than the oppressed. One might critique Orwell for failing to better account for the damage imperialism causes the oppressed, but one might also credit Orwell for discussing the evils of imperialism in a manner that might make its costs seem real to his audience, which, at least initially, consisted mostly of beneficiaries of British imperialism.

In writing about the experience of imperialist oppression from the perspective of the oppressor, Orwell often returns to several themes.

The first is the role of experience. Orwell argues that one can only really come to hate imperialism by being a part of imperialism (Wigan Pier, 144). One can doubt this is true, while still granting Orwell the emotional force of the point that experiencing imperialism firsthand can give one a particularly vivid understanding of imperialism’s “tyrannical injustice,” because one is, as Orwell put it, “part of the actual machinery of despotism” (Wigan Pier, 145).

Playing such a role in the machinery of despotism connects to a second theme in Orwell’s writing on imperialism: the guilt and moral damage caused by being an imperialist oppressor. In Wigan Pier, for example, Orwell writes the following about his state of mind after working for five years for the British Imperial Police in Burma:

I was conscious of an immense weight of guilt that I had got to expiate. I suppose that sounds exaggerated; but if you do for five years a job that you thoroughly disapprove of, you will probably feel the same. I had reduced everything to a simple theory that the oppressed are always right and the oppressors always wrong: a mistaken theory, but the natural result of being one of the oppressors yourself (Wigan Pier, 148).

A third theme in Orwell’s writing about imperialism is about ways in which imperialist oppressors—despite having economic and political power over the oppressed—themselves become controlled, in some sense, by those whom they oppress. For example, in “Shooting an Elephant” Orwell presents himself as having shot an elephant that got loose in a Burmese village merely in order to satisfy the local people’s expectations, even though he doubted shooting the elephant was necessary. Orwell writes of the experience that “I perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own freedom that he destroys…For it is the condition of his rule that he shall spend his life trying to impress the ‘natives’ and so in every crisis he has got to do what the ‘natives’ expect of him.”

Thus, on Orwell’s account, no one is free under conditions of imperialist oppression—neither the oppressors nor the oppressed. The oppressed experience what Orwell calls in Wigan Pier “double oppression” because imperialist power not only leads to substantive injustice being committed against oppressed people, but to injustices committed by unwanted foreign invaders (Wigan Pier, 147). Oppressors, on the other hand, feel the need to conform to their role as oppressors despite their guilt, shame, and a desire to do otherwise (which Orwell seemed to think were near universal feelings among the British imperialists of his day).

Notably, some of Orwell’s earliest articulations of how pressures to socially conform can lead to suppression of freedom of speech occur in the context of his discussions of the lack of freedom experienced by imperialist oppressors. For example, in “Shooting an Elephant,” Orwell wrote that he “had to think out [his] problems in the utter silence that is imposed on every Englishman in the East.” And in Wigan Pier, he wrote that for British imperialists in India there was “no freedom of speech” and that “merely to be overheard making a seditious remark may damage [one’s] career” (144).

c. Socialism

From the mid-1930s until the end of his life, Orwell advocated for socialism. In doing so, he sought to defend socialism against mischaracterization. Thus, to understand Orwell’s views on socialism, one must understand both what Orwell thought socialism was and what he thought it was not.

Orwell offers his most succinct definition of socialism in Wigan Pier as meaning “justice and liberty.” The sense of justice he had in mind included not only economic justice, but also social and political justice. Inclusion of the word “liberty” in his definition of socialism helps explain why elsewhere Orwell specifies that he is a democratic socialist. For Orwell, democratic socialism is a political order that provides social and economic equality while also preserving robust personal freedom. Orwell was particularly concerned to preserve what we might call the intellectual freedoms: freedom of thought, freedom of expression, and freedom of the press.

Orwell’s most detailed account of socialism, at least as he envisioned it for Great Britain, is included in his essay “The Lion and the Unicorn.” Orwell notes that socialism is usually defined as “common ownership of the means of production” (Part II, Section I), but he takes this definition to be insufficient. For Orwell, socialism also requires political democracy, the removal of hereditary privilege in the United Kingdom’s House of Lords, and limits on income inequality (Part II, Section I).

For Orwell, one of the great benefits of socialism seems to be the removal of class-based prejudice. Orwell saw this as necessary for the creation of fellow feeling between people within a society. Given his experiences within socially stratified early twentieth century English culture, Orwell saw the importance of removing both economic and social inequality in achieving a just and free society.

This is reflected in specific proposals that Orwell suggested England adopt going into World War II. (In “The Lion and the Unicorn,” Orwell typically refers to England or Britain, rather than the United Kingdom as a whole. This is true of much of Orwell’s work.) These proposals included:

I. Nationalization of land, mines, railways, banks and major industries.

II. Limitation of incomes, on such a scale that the highest tax-free income in Britain does not exceed the lowest by more than ten to one.

III. Reform of the educational system along democratic lines.

IV. Immediate Dominion status for India, with power to secede when the war is over.

V. Formation of an Imperial General Council, in which the colored peoples are to be represented.

VI. Declaration of formal alliance with China, Abyssinia and all other victims of the Fascist powers. (Part III, Section II)

Orwell viewed these as steps that would turn England into a “socialist democracy.”

In the latter half of Wigan Pier, Orwell argues that many people are turned off by socialism because they associate it with things that are not inherent to socialism. Orwell contends that socialism does not require the promotion of mechanical progress, nor does it require a disinterest in parochialism or patriotism. Orwell also views socialism as distinct from both Marxism and Communism, viewing the latter as a form of totalitarianism that at best puts on a socialist façade.

Orwell contrasts socialism with capitalism, which he defines in “The Lion and the Unicorn” as “an economic system in which land, factories, mines and transport are owned privately and operated solely for profit.” Orwell’s primary reason for opposing capitalism is his contention that capitalism “does not work” (Part II, Section I). Orwell offers some theoretical reasons to think capitalism does not work (for example, “It is a system in which all the forces are pulling in opposite directions and the interests of the individual are as often as not totally opposed to those of the State” (Part II, Section I). But the core of Orwell’s argument against capitalism is grounded in claims about experience. In particular, he argues that capitalism left Britain ill-prepared for World War II and led to unjust social inequality.

d. Totalitarianism

Orwell conceives of totalitarianism as a political order focused on absolute power and control. The totalitarian attitude is exemplified by the antagonist, O’Brien, in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The fictional O’Brien is a powerful government official who uses torture and manipulation to gain power over the thoughts and actions of the protagonist, Winston Smith, a low-ranking official working in the propaganda-producing “Ministry of Truth.” Significantly, O’Brien treats his desire for power as an end in itself. O’Brien represents power for power’s sake.

Orwell recognized that because totalitarianism seeks complete power and total control, it is incompatible with the rule of law—that is, that totalitarianism is incompatible with stable laws that apply to everyone, including political leaders themselves. In “The Lion and the Unicorn,” Orwell writes of “[t]he totalitarian idea that there is no such thing as law, there is only power.” While law limits a ruler’s power, totalitarianism seeks to obliterate the limits of law through the uninhibited exercise of power. Thus, the fair and consistent application of law is incompatible with the kind of complete centralized power and control that is the final aim of totalitarianism.

Orwell sees totalitarianism as a distinctly modern phenomenon. For Orwell, Soviet Communism, Italian Fascism, and German Nazism were the first political orders seeking to be truly totalitarian. In “Literature and Totalitarianism,” Orwell describes the way in which totalitarianism differs from previous forms of tyranny and orthodoxy as follows:

The peculiarity of the totalitarian state is that though it controls thought, it doesn’t fix it. It sets up unquestionable dogmas, and it alters them from day to day. It needs the dogmas, because it needs absolute obedience from its subjects, but it can’t avoid the changes, which are dictated by the needs of power politics (“Literature and Totalitarianism”).

In pursuing complete power, totalitarianism seeks to bend reality to its will. This requires treating political power as prior to objective truth.

But Orwell denies that truth and reality can bend in the ways that the totalitarian wants them to. Objective truth itself cannot be obliterated by the totalitarian (although perhaps the belief in objective truth can be). It is for this reason that Orwell writes in “Looking Back on the Spanish War” that “However much you deny the truth, the truth goes on existing, as it were, behind your back, and you consequently can’t violate it in ways that impair military efficiency.” Orwell considers this to be one of the two “safeguards” against totalitarianism. The other safeguard is “the liberal tradition,” by which Orwell means something like classical liberalism and its protection of individual liberty.

Orwell understood that totalitarianism could be found on the political right and left. For Orwell, both Nazism and Communism were totalitarian (see, for example, “Raffles and Miss Blandish”). What united both the Soviet Communist and the German Nazi under the banner of totalitarianism was a pursuit of complete power and the ideological conformity that such power requires. Orwell recognized that such power required extensive capacity for surveillance, which explains why means of surveillance such as the “telescreen” and the “Thought Police” play a large role in the plot of Nineteen Eighty-Four. (For a discussion of Orwell as an early figure in the ethics of surveillance, see the article on surveillance ethics.)

e. Nationalism

One of Orwell’s more often cited contributions to political thought is his development of the concept of nationalism. In “Notes on Nationalism,” Orwell describes nationalism as “the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil and recognizing no other duty than that of advancing its interests.” In “The Sporting Spirit,” Orwell adds that nationalism is “the lunatic modern habit of identifying oneself with large power units and seeing everything in terms of competitive prestige.”

In both these descriptions Orwell describes nationalism as a “habit.” Elsewhere, he refers to nationalism more specifically as a “habit of mind.” This habit of mind has at least two core features for Orwell—namely, (1) rooting one’s identity in group membership rather than in individuality, and (2) prioritizing advancement of the group one identifies with above all other goals. It is worth examining each of these features in more detail.

For Orwell, nationalism requires subordination of individual identity to group identity, where the group one identifies with is a “large power unit.” Importantly, for Orwell this large power unit need not be a nation. Orwell considered nationalism to be prevalent in movements as varied as “Communism, political Catholicism, Zionism, Antisemitism, Trotskyism and Pacifism” (“Notes on Nationalism”). What is required is that the large power unit be something that individuals can adopt as the center of their identity. This can happen both via a positive attachment (that is, by identifying with a group), but it can also happen via negative rejection (that is, by identifying as against a group). This is how, for example, Orwell’s list of movements with nationalistic tendencies could include both Zionism and Antisemitism.

But making group membership the center of one’s identity is not on its own sufficient for nationalism as Orwell understood it. Nationalists make advancement of their group their top priority. For this reason, Orwell states that nationalism “is inseparable from the desire for power” (“Notes on Nationalism”). The nationalist stance is aggressive. It seeks to overtake all else. Orwell contrasts the aggressive posture taken by nationalism with a merely defensive posture that he refers to as patriotism. For Orwell, patriotism is “devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people” (“Notes on Nationalism”). He sees patriotism as laudable but sees nationalism as dangerous and harmful.

In “Notes on Nationalism,” Orwell writes that the “nationalist is one who thinks solely, or mainly, in terms of competitive prestige.” As a result, the nationalist “may use his mental energy either in boosting or in denigrating—but at any rate his thoughts always turn on victories, defeats, triumphs and humiliations.” In this way, Orwell’s analysis of nationalism can be seen as a forerunner for much of the contemporary discussion about political tribalism and negative partisanship, which occurs when one’s partisan identity is primarily driven by dislike of one’s outgroup rather than support for one’s ingroup (Abramowitz and Webster).

It is worth noting that Orwell takes his own definition of nationalism to be somewhat stipulative. Orwell started with a concept that he felt needed to be discussed and decided that nationalism was the best name for this concept. Thus, his discussions of nationalism (and patriotism) should not be considered conceptual analysis: rather, these discussions are more akin to what is now often called conceptual ethics or conceptual engineering.

3. Epistemology and Philosophy of Mind

Just as 1936-37 marked a shift toward the overtly political in Orwell’s writing, so too those years marked a shift toward the overtly epistemic. Orwell was acutely aware of how powerful entities, such as governments and the wealthy, were able to influence people’s beliefs. Witnessing both the dishonesty and success of propaganda about the Spanish Civil War, Orwell worried that these entities had become so successful at controlling others’ beliefs that “The very concept of objective truth [was] fading out of the world” (“Looking Back at the Spanish War”). Orwell’s desire to defend truth, alongside his worries that truth could not be successfully defended in a completely totalitarian society, culminate in the frequent epistemological ruminations of Winston Smith, the fictional protagonist in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

a. Truth, Belief, Evidence, and Reliability

Orwell’s writing routinely employs many common epistemic terms from philosophy, including “truth,” “belief,” “knowledge,” “facts,” “evidence,” “testimony,” “reliability,” and “fallibility,” among others, yet he also seems to have taken for granted that his audience would understand these terms without defining them. Thus, one must look at how Orwell uses these terms in context in order to figure out what he meant by them.

To start with the basics, Orwell distinguishes between belief and truth and rejects the view that group consensus makes something true. For example, in his essay on Rudyard Kipling, Orwell writes “I am not saying that that is a true belief, merely that it is a belief which all modern men do actually hold.” Such a statement assumes that truth is a property that can be applied to beliefs, that truth is not grounded on acceptance by a group, and that just because someone believes something does not make it true.

On the contrary, Orwell seems to think that truth is, in an important way, mind-independent. For example, he writes that, “However much you deny the truth, the truth goes on existing, as it were, behind your back, and you consequently can’t violate it in ways that impair military efficiency” (“Looking Back on the Spanish War”). For Orwell, truth is derived from the way the world is. Because the world is a certain way, when our beliefs fail to accord with reality, our actions fail to align with the way the world is. This is why rejecting objective truth wholesale would, for instance, “impair military efficiency.” You can claim there are enough rations and munitions for your soldiers, but if, in fact, there are not enough rations and munitions for your soldiers, you will suffer military setbacks. Orwell recognizes this as a pragmatic reason to pursue objective truth.

Orwell does not talk about justification for beliefs as academic philosophers might. However, he frequently appeals to quintessential sources of epistemic justification—such as evidence and reliability—as indicators of a belief’s worthiness of acceptance and its likelihood of being true. For example, Orwell suggests that if one wonders whether one harbors antisemitic attitudes that one should “start his investigation in the one place where he could get hold of some reliable evidence—that is, in his own mind” (“Antisemitism”). Regardless of what one thinks of Orwell’s strategy for detecting antisemitism, this passage shows Orwell’s assumption that, at least some of the time, we can obtain reliable evidence via introspection.

Orwell’s writings on the Spanish Civil War provide a particularly rich set of texts from which to learn about the conditions under which Orwell thinks we can obtain reliable evidence. This is because Orwell was seeking to help readers (and perhaps also himself) separate truth from lies about what happened during that war. In so doing, Orwell offers an epistemology of testimony. For example, he writes:

Nor is there much doubt about the long tale of Fascist outrages during the last ten years in Europe. The volume of testimony is enormous, and a respectable proportion of it comes from the German press and radio. These things really happened, that is the thing to keep one’s eye on (“Looking Back on the Spanish War”).

Here, Orwell appeals to both the volume and the source of testimony as reason to have little doubt that fascist outrages had been occurring in Europe. Orwell also sometimes combines talk of evidence via testimony with other sources of evidence—like first-hand experience—writing, for example, “I have had accounts of the Spanish jails from a number of separate sources, and they agree with one another too well to be disbelieved; besides I had a few glimpses into one Spanish jail myself” (Homage to Catalonia, 179).

While recognizing the epistemic challenges posed by propaganda and self-interest, Orwell was no skeptic about knowledge. He was comfortable attributing knowledge to agents and referring to states of affairs as facts, writing, for example: “These facts, known to many journalists on the spot, went almost unmentioned to the British press” (“The Prevention of Literature”). Orwell was less sanguine about our ability to know with certainty, writing, for example, “[It] is difficult to be certain about anything except what you have seen with your own eyes, and consciously or unconsciously everyone writes as a partisan” (Homage to Catalonia, 195). This provides reason to think that Orwell was a fallibilist about knowledge—that is, someone who thinks you can know a proposition even while lacking certainty about the truth of that proposition. (For example, a fallibilist might claim to know she has hands but still deny that she is certain that she has hands.)

Orwell saw democratic socialism as responsive to political and economic facts, whereas he saw totalitarianism as seeking to bend the facts to its will. Thus, Orwell’s promotion of objective truth is closely tied to his promotion of socialism over totalitarianism. This led Orwell to confess that he was frightened by “the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world.” For Orwell, acknowledging objective truth requires acknowledging reality and the limitations reality places on us. Reality says that 2 + 2 = 4 and not that 2 + 2 = 5.

In this way, Orwell uses the protagonist of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith, to express his views on the relationship between truth and freedom. An essential part of freedom for Orwell is the ability to think and to speak the truth. Orwell was especially prescient in identifying hindrances to the recognition of truth and the freedom that comes with it. These threats include nationalism, propaganda, and technology that can be used for constant surveillance.

b. Ignorance and Experience

Writing was a tool Orwell used to try to dispel his readers’ ignorance. He was a prolific writer who wrote many books, book reviews, newspaper editorials, magazine articles, radio broadcasts, and letters during a relatively short career. In his writing, he sought to disabuse the rich of ignorant notions about the poor; he sought to correct mistaken beliefs about the Spanish Civil War that had been fueled by fascist propaganda; and he sought to counteract inaccurate portrayals of democratic socialism and its relationship to Soviet Communism.

Orwell’s own initial ignorance on these matters had been dispelled by life experience. As a result, he viewed experience as capable of overcoming ignorance. He seemed to believe that testimony about experience also had the power to help those who received testimony to overcome their ignorance. Thus, Orwell sought to testify to his experiences in a way that might help counteract the inaccurate perceptions of those who lacked experience about matters to which he testified in his writing.

As discussed earlier, Orwell believed that middle- and upper-class people in Britain were largely ignorant about the character and circumstances of those living in poverty, and that what such people imagined poverty to be like was often inaccurate. Concerning his claim that the rich and poor do not have different natures or different moral character, Orwell writes that “Everyone who has mixed on equal terms with the poor knows this quite well. But the trouble is that intelligent, cultivated people, the very people who might be expected to have liberal opinions, never do mix with the poor” (Down and Out, 120).

Orwell made similar points about many other people and circumstances. He argued that the job of low-level kitchen staff in French restaurants that appeared easy from the outside was actually “astonishingly hard” (Down and Out, 62), that actually watching coal miners work could cause a member of the English to doubt their status as “a superior person” (Wigan Pier, 35), and that working in a bookshop was a good way to disabuse oneself of the fantasy that working in a bookshop was a paradise (see “Bookshop Memories”).

There is an important metacommentary that is hard to overlook concerning Orwell’s realization that experience is often necessary to correct ignorance. During his lifetime, Orwell amassed an eclectic set of experiences that helped him to understand better the perspective of those in a variety of professions and social classes. This allowed him to empathize with the plight of a wide variety of white men. However, try as he might, Orwell could not ever experience what it was like to be a woman, person of color, or queer-identified person in any of these circumstances. Feminist critics have rightfully called attention to the misogyny and racism that is common in Orwell’s work (see, for example, Beddoe 1984, Campbell 1984, and Patai 1984). Orwell’s writings were also often homophobic (see, for example, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, chapter 1; Taylor 2003, 245). In addition, critics have pointed to antisemitism and anti-Catholicism in his writing (see, for example, Brennan 2017). Thus, Orwell’s insights about the epistemic power of experience also help explain significant flaws in his corpus, due to the limits of his own experience and imagination, or perhaps more simply due to his own prejudices.

c. Embodied Cognition

Orwell’s writing is highly consonant with philosophical work emphasizing that human cognition is embodied. For Orwell, unlike Descartes, we are not first and foremost a thinking thing. Rather, Orwell writes that “A human being is primarily a bag for putting food into; the other functions and faculties may be more godlike, but in point of time they come afterwards” (Wigan Pier, 91-92).

The influence of external circumstances and physical conditions on human cognition plays a significant role in all of Orwell’s nonfiction books as well as in Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. In Homage to Catalonia, Orwell relays how, due to insufficient sleep as a soldier in the Spanish Republican Army, “One grew very stupid” (43). In Down and Out, Orwell emphasized how the physical conditions of a poor diet make it so that you can “interest yourself in nothing” so that you become “only a belly with a few accessory organs” (18-19). And in Wigan Pier, Orwell argues that even the “best intellect” cannot stand up against the “debilitating effect of unemployment” (81). This, he suggests, is why it is hard for the unemployed to do things like write books. They have the time, but according to Orwell, writing books requires peace of mind in addition to time. And Orwell believed that the living conditions for most unemployed people in early twentieth century England did not afford such peace of mind.

Orwell’s emphasis on embodied cognition is another way in which he recognizes the tight connection between the political and the epistemic. In Animal Farm, for example, the animals are initially pushed toward their rebellion against the farmer after they are left unfed, and their hunger drives them to action. And Napoleon, the aptly named pig who eventually gains dictatorial control over the farm, keeps the other animals overworked and underfed as a way of making them more pliable and controllable. Similarly, in Nineteen Eighty-Four, while food is rationed, gin is in abundance for party members. And the physical conditions of deprivation and torture are used to break the protagonist Winston Smith’s will to the point that his thoughts become completely malleable. Epistemic control over citizens’ minds gives the Party power over the physical conditions of the citizenry, with control over the physical conditions of the citizenry in turn helping cement the Party’s epistemic control over citizens.

d. Memory and History

Orwell treats memory as a deeply flawed yet invaluable faculty, because it is often the best or only way to obtain many truths about the past. The following passage is paradigmatic of his position: “Treacherous though memory is, it seems to me the chief means we have of discovering how a child’s mind works. Only by resurrecting our own memories can we realize how incredibly distorted is the child’s vision of the world” (“Such, Such Were the Joys”).

In his essay “My Country Right or Left,” Orwell expresses wariness about the unreliability of memories, yet he also seems optimistic about our ability to separate genuine memories form false interpolations with concentration and reflection. Orwell argued that over time British recollection of World War I had become distorted by nostalgia and post hoc narratives. He encouraged his readers to “Disentangle your real memories from later accretions,” which suggests he thinks such disentangling is at least possible. This is reinforced by his later claim that he was able to “honestly sort out my memories and disregard what I have learned since” about World War I (“My Country Right or Left”).

As these passages foreshadow, Orwell sees both the power and limitation of memory as politically significant. Accurate memories can refute falsehoods and lies, including falsehoods and lies about history. But memories are also susceptible to corruption, and cognitive biases may allow our memories to be corrupted in predictable and useful ways by those with political power. Orwell worried that totalitarian governments were pushing a thoroughgoing skepticism about the ability to write “true history.” At the same time, Orwell also noted that these same totalitarian governments used propaganda to try to promote their own accounts of history—accounts which often were wildly discordant with the facts (see, for example, “Looking Back at the Spanish War,” Section IV).

The complex relationship between truth, memory, and history in a totalitarian regime is a central theme in Nineteen Eighty-Four. One of the protagonist’s primary ways of resisting the patent lies told by the Party was clinging to memories that contradicted the Party’s false claims about the past. The primary antagonist, O’Brien, sought to eliminate Winston’s trust in his own memories by convincing him to give up on the notion of objective truth completely. Like many of the key themes in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell discussed the relationship between truth, memory, and history under totalitarianism elsewhere. Notable examples include his essays “Looking Back on the Spanish War,” “Notes on Nationalism,” and “The Prevention of Literature.”

4. Philosophy of Language

Orwell had wide-ranging interests in language. These interests spanned the simple “joy of mere words” to the political desire to use language “to push the world in a certain direction” (“Why I Write”). Orwell studied how language could both obscure and clarify, and he sought to identify the political significance language had as a result.

a. Language and Thought

For Orwell, language and thought significantly influence one another. Our thought is a product of our language, which in turn is a product of our thought.

“Politics and the English Language” contains Orwell’s most explicit writing about this relationship. In the essay, Orwell focuses primarily on language’s detrimental effects on thought and vice versa, writing, for example, that the English language “becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts” and that “If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” But despite this focus on detrimental effects, Orwell’s purpose in “Politics and the English Language” is ultimately positive. His “point is that the process [of corruption] is reversible.” Orwell believed the bad habits of thought and writing he observed could “be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble.” Thus, the essay functions, in part, as a guide for doing just that.

This relationship between thought and language is part of a larger three-part relationship Orwell identified between language, thought, and politics (thus why the article is entitled “Politics and the English Language”). Just as thought and language mutually influence one another, so too do thought and politics. Thus, through the medium of thought, politics and language influence one another too. Orwell argues that if one writes well, “One can think more clearly,” and in turn that “To think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration.” This makes good writing a political task. Therefore, Orwell concludes that for those in English-speaking political communities, “The fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.” An analogous principle holds for those living in political communities that use other languages. For example, based on his theory about the bi-directional influence that language, thought, and politics have upon one another, Orwell wrote that he expected “that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.” (“Politics and the English Language” was published shortly after the end of World War II.)

Orwell’s desire to avoid bad writing is not the desire to defend “standard English” or rigid rules of grammar. Rather, Orwell’s chief goal is for language users to aspire “to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way about.” Communicating clearly and precisely requires conscious thought and intention. Writing in a way that preserves one’s meaning takes work. Simply selecting the words, metaphors, and phrases that come most easily to mind can obscure our meaning from others and from ourselves. Orwell describes a speaker who is taken over so completely by stock phrases, stale metaphors, and an orthodox party line as someone who:

Has gone some distance toward turning himself into a machine. The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved, as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. If the speech he is making is one that he is accustomed to make over and over again, he may be almost unconscious of what he is saying.

Orwell explores this idea in Nineteen Eighty-Four with the concept of “duckspeak,” which is defined as a speaker who merely quacks like a duck when repeating orthodox platitudes.

b. Propaganda

Like many terms that were important to him, Orwell never defines what he means by “propaganda,” and it is not clear that he always used the term consistently. Still, Orwell was an insightful commentator on how propaganda functioned and why understanding it mattered.

Orwell often used the term “propaganda” pejoratively. But this does not mean that Orwell thought propaganda was always negative. Orwell wrote that “All art is propaganda,” while denying that all propaganda was art (“Charles Dickens”). He held that the primary aim of propaganda is “to influence contemporary opinion” (“Notes on Nationalism”). Thus, Orwell’s sparsest conception of propaganda seems to be messaging aimed at influencing opinion. Such messages need not be communicated only with words. For example, Orwell frequently pointed out the propagandistic properties of posters, which likely inspired his prose about the posters of Big Brother in Nineteen Eighty-Four. This sparse conception of propaganda does not include conditions that other accounts may include, such as that the messaging must be in some sense misleading or that the attempt to influence must be in some sense manipulative (compare with Stanley 2016).

Orwell found much of the propaganda of his age troubling because of the deleterious effects he believed propaganda was having on individuals and society. Propaganda functions to control narratives and, more broadly, thought. Orwell observed that sometimes this was done by manipulating the effect language was apt to have on audiences.

He noted that dictators like Hitler and Stalin committed callous murders, but never referred to them as such, preferring instead to use terms like “liquidation,” “elimination,” or “some other soothing phrase” (“Inside the Whale”). But at other times, he noted that propaganda consisted of outright lies. In lines reminiscent of the world he would create in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell described the situation he observed as follows: “Much of the propagandist writing of our time amounts to plain forgery. Material facts are suppressed, dates altered, quotations removed from their context and doctored so as to change their meaning” (“Notes on Nationalism”). Orwell also noted that poorly done propaganda could not only fail but could also backfire and repel the intended audience. He was often particularly hard on his allies on the political left for propaganda that he thought most working-class people found off-putting.

5. Philosophy of Art and Literature

Orwell viewed aesthetic value as distinct from other forms of value, such as moral and economic. He most often discussed aesthetic value while discussing literature, which he considered a category of art. Importantly, Orwell did not think that the only way to assess literature was on its aesthetic merits. He thought literature (along with other kinds of art and writing) could be assessed morally and politically as well. This is perhaps unsurprising given his desire “to make political writing into an art” (“Why I Write”).

a. Value of Art and Literature

That Orwell views aesthetic value as distinct from moral value is clear. Orwell wrote in an essay on Salvador Dali that one “ought to be able to hold in one’s head simultaneously the two facts that Dali is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being” (“Benefit of Clergy”). What is less clear is what Orwell considers the grounds for aesthetic value. Orwell appears to have been of two minds about this. At times, Orwell seemed to view aesthetic values as objective but ineffable. At other times, he seemed to view aesthetic value as grounded subjectively on the taste of individuals.

For example, Orwell writes that his own age was one “in which the average human being in the highly civilized countries is aesthetically inferior to the lowest savage” (“Poetry and the Microphone”). This suggests some culturally neutral perspective from which aesthetic refinement can be assessed. In fact, Orwell seems to think that one’s cultural milieu can enhance or corrupt one’s aesthetic sensitivity, writing that the “ugliness” of his society had “spiritual and economic causes,” and that “Aesthetic judgements, especially literary judgements, are often corrupted in the same way as political ones” (“Poetry and the Microphone”; “Notes on Nationalism”). Orwell even held that some people “have no aesthetic feelings whatever,” a condition to which he thought the English were particularly susceptible (“The Lion and the Unicorn”). On the other hand, Orwell also wrote that “Ultimately there is no test of literary merit except survival, which is itself an index to majority opinion” (“Lear, Tolstoy, and the Fool”). This suggests that perhaps aesthetic value bottoms out in intersubjectivity.

There are ways of softening this tension, however, by noting the different ways in which Orwell thinks literary merit can be assessed. For example, Orwell writes the following:

Supposing that there is such a thing as good or bad art, then the goodness or badness must reside in the work of art itself—not independently of the observer, indeed, but independently of the mood of the observer. In one sense, therefore, it cannot be true that a poem is good on Monday and bad on Tuesday. But if one judges the poem by the appreciation it arouses, then it can certainly be true, because appreciation, or enjoyment, is a subjective condition which cannot be commanded (“Politics vs. Literature”).

This suggests literary merit can be assessed either in terms of artistic merit or in terms of subjective appreciation and that these two forms of assessment need not generate matching results.

This solution, however, still leaves the question of what justifies artistic merit unanswered. Perhaps the best answer available comes in Orwell’s essay on Charles Dickens. There, Orwell concluded that “As a rule, an aesthetic preference is either something inexplicable or it is so corrupted by non-aesthetic motives as to make one wonder whether the whole of literary criticism is not a huge network of humbug.” Here, Orwell posits two potential sources of aesthetic preference: one of which is humbug and one of which is inexplicable. This suggests that Orwell may favor a view of aesthetic value that is ultimately ineffable. But even if the grounding of aesthetic merit is inexplicable, Orwell seems to think we can still judge art on aesthetic, as well as moral and political, grounds.

b. Literature and Politics

Orwell believed that there was “no such thing as genuinely non-political literature” (“The Prevention of Literature”). This is because Orwell thought that all literature sent a political message, even if the message was as simple as reinforcing the status quo. This is part of what Orwell means when he says that all art is propaganda. For Orwell, all literature—like all art—seeks to influence contemporary opinion. For this reason, all literature is political.

Because all literature is political, Orwell thought that a work of literature’s political perspective often influenced the level of merit a reader assigned to it. More specifically, people tend to think well of literature that agrees with their political outlook and think poorly of literature that disagrees with it. Orwell defended this position by pointing out “the extreme difficulty of seeing any literary merit in a book that seriously damages your deepest beliefs” (“Inside the Whale”).

But just as literature could influence politics through its message, so too politics could and did influence literature. Orwell argued that all fiction is “censored in the interests of the ruling class” (“Boys’ Weeklies”). For Orwell, this was troubling under any circumstances, but was particularly troublesome when the state exhibited totalitarian tendencies. Orwell thought that the writing of literature became impossible in a state that was genuinely authoritarian. This was because in a totalitarian regime there is no intellectual freedom and there is no stable set of shared facts. As a result, Orwell held that “The destruction of intellectual liberty cripples the journalist, the sociological writer, the historian, the novelist, the critic, and the poet, in that order” (“The Prevention of Literature”).

Thus, Orwell’s views on the mutual connections between politics, thought, and language extend to art—especially written art. These things affect literature so thoroughly that certain political orders make writing literature impossible. But literature, in turn, has the power to affect these core aspects of human life.

6. Orwell’s Relationship to Academic Philosophy

Orwell’s relationship to academic philosophy has never been a simple matter. Orwell admired Bertrand Russell, yet he wrote in response to a difficulty he encountered reading one of Russell’s books that it was “the sort of thing that makes me feel that philosophy should be forbidden by law” (Barry 2021). Orwell considered A. J. Ayer a “great friend,” yet Ayer said that Orwell “wasn’t interested in academic philosophy in the very least” and believed that Orwell thought academic philosophy was “rather a waste of time” (Barry 2022; Wadhams 2017, 205). And Orwell referred to Jean Paul Sartre as “a bag of wind” to whom he was going to give “a good [metaphorical] boot” (Tyrrell 1996).

Some have concluded that Orwell was uninterested in or incapable of doing rigorous philosophical work. Bernard Crick, one of Orwell’s biographers who was himself a philosopher and political theorist, concluded that Orwell would “have been incapable of writing a contemporary philosophical monograph, scarcely of understanding one,” observing that “Orwell chose to write in the form of a novel, not in the form of a philosophical tractatus” (Crick 1980, xxvii). This is probably all true. But this does not mean that Orwell’s work was not influenced by academic philosophy. It was. This also does not mean that Orwell’s work is not valuable for academic philosophers. It is.

Aside from critical comments about Marx, Orwell tended not to reference philosophers by name in his work (compare with Tyrrell 1996). As such, it can be hard to determine the extent to which he was familiar with or was influenced by such thinkers. Crick concludes that Orwell was “innocent of reading either J.S. Mill or Karl Popper,” yet seemed independently to reach some similar conclusions (Crick 1980, 351). But while there is little evidence of Orwell’s knowledge of the history of philosophy, there is plenty of evidence of his familiarity with at least some philosophical work written during his own lifetime. Orwell reviewed books by both Sartre and Russell (Tyrrell 1996, Barry 2021), and Orwell’s library at the time of his death included several of Russell’s books (Barry 2021). By examining Orwell’s knowledge of, interactions with, and writing about Russell, Peter Brian Barry has offered compelling arguments that Russell influenced Orwell’s views on moral psychology, metaethics, and metaphysics (Barry 2021; Barry 2022). And as others have noted, there is a clear sense in which Orwell’s writing deals with philosophical themes and seeks to work through philosophical ideas (Tyrrell 1996; Dwan 2010, 2018; Quintana 2018, 2020; Satta 2021a, 2021c).

These claims can be made consistent by distinguishing being an academic philosopher and being a philosophical thinker in some other sense. Barry puts the point well, noting that Orwell’s lack of interest in “academic philosophy” is “consistent with Orwell being greatly interested in normative public philosophy, including social and political philosophy.” David Dwan makes a similar point, preferring to call Orwell a “political thinker” rather than a “political philosopher” and arguing that we “can map the challenges he [Orwell] presents for political philosophy without ascribing to him a rigour to which he never aspired” (Dwan 2018, 4).

Philosophers working in political philosophy, philosophy of language, epistemology, ethics, and metaphysics, among other fields, have used and discussed Orwell’s writing. Richard Rorty, for example, devoted a chapter to Orwell in his 1989 book Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, where he claimed that Orwell’s “description of our political situation—of the dangers and options at hand—remains as useful as any we possess” (Rorty 1989, 170). For Rorty, part of Orwell’s value was that he “sensitized his [readers] to a set of excuses for cruelty,” which helped reshape our political understanding (Rorty 1989, 171). Rorty also saw Orwell’s work as helping show readers that totalitarian figures like 1984’s O’Brien were possible (Rorty 1989, 175-176).

But perhaps the chief value Rorty saw in Orwell’s work was the way in which it showed the deep human value in having the ability to say what you believe and the “ability to talk to other people about what seems true to you” (Rorty 1989, 176). That is to say, Rorty recognized the value that Orwell placed on intellectual freedom. That said, Rorty here seeks to morph Orwell into his own image by suggesting that Orwell cares merely about intellectual freedom and not about truth. Rorty argues that, for Orwell, “It does not matter whether ‘two plus two is four’ is true” and that Orwell’s “question about ‘the possibility of truth’ is a red herring” (Rorty 1989, 176, 182). Rorty’s claims that Orwell was not interested in truth have not been widely adopted. In fact, his position has prompted philosophical defense of the much more plausible view that Orwell cared about truth and considered truth to be, in some sense, real and objective (see, for example, van Inwagen 2008; Dwan 2018, 160-163; confer Conant 2020).

In philosophy of language, Derek Ball has identified Orwell as someone who recognized that “A particular metasemantic fact might have certain social and political consequences” (Ball 2021, 45). Ball also notes that on one plausible reading, Orwell seems to accept both linguistic determinism—“the claim that one’s language influences or determines what one believes, in such a way that speakers of different languages will tend to possess different (and potentially incompatible) beliefs precisely because they speak different languages”—and linguistic relativism—”the claim that one’s language influences or determines what concepts one possesses, and hence what thoughts one is capable of entertaining, in such a way that speakers of different languages frequently possess entirely different conceptual repertoires precisely because they speak different languages” (Ball 2021, 47).

Ball’s points are useful ways to frame some of Orwell’s key philosophical commitments about the interrelationship between language, thought, and politics. Ball’s observations accord with Judith Shklar’s claim that the plot of 1984 “is not really just about totalitarianism but rather about the practical implications of the notion that language structures all our knowledge of the phenomenal world” (Shklar 1984). Similarly, in his work on manipulative speech, Justin D’Ambrosio has noted the significance of Orwell’s writing for politically relevant philosophy of language (D’Ambrosio unpublished manuscript). These kinds of observations about Orwell’s views may become increasingly significant in academic philosophy, given the current development of political philosophy of language as an area of study (see, for example, Khoo and Sterken 2021).

Philosophers have also noted the value of Orwell’s work for epistemology. Martin Tyrrell argues that much of Orwell’s “later and better writing amounts to an attempt at working out the political consequences of what are essentially philosophical questions,” citing specifically epistemological questions like “When and what should we doubt?” and “When and what should we believe?” (Tyrrell 1996). Simon Blackburn has noted the significance of Orwell’s worries about truth for political epistemology, concluding that “The answer to Orwell’s worry [about the possibility of truth] is not to give up inquiry, but to conduct it with even more care, diligence, and imagination” (Blackburn 2021, 70). Mark Satta has documented Orwell’s recognition of the epistemic point that our physical circumstances as embodied beings influence our thoughts and beliefs (Satta 2021a).

As noted earlier, Orwell treats moral value as a domain distinct from other types of value, such as the aesthetic. Academic philosophers have studied and productively used Orwell’s views in the field of ethics. Barry argues that Orwell’s moral views are a form of threshold deontology, on which certain moral norms (such as telling the truth) must be followed, except on occasions where not following such norms is necessary to prevent horrendous results. Barry also argues that Orwell’s moral norms come from Orwell’s humanist account of moral goodness, which grounds moral goodness in what is good for human beings. This account of Orwell’s ethical commitments accords with Dwan’s view that, while Orwell engaged in broad criticism of moral consequentialism, there were limits to Orwell’s rejection of consequentialism, such as Orwell’s acceptance that some killing is necessary in war (Dwan 2018, 17-19).

Philosophers have also employed Orwell’s writing at the intersection of ethics and political philosophy. For example, Martha Nussbaum identifies the ethical and political importance given to emotions in 1984. She examines how Winston Smith looks back longingly at a world which contained free expression of emotions like love, compassion, pity, and fellow feeling, while O’Brien seeks to establish a world in which the dominant (perhaps only) emotions are fear, rage, triumph, and self-abasement (Nussbaum 2005). Oriol Quintana has identified the importance of human recognition in Orwell’s corpus and has used this in an account of the ethics of solidarity (Quintana 2018). Quintana has also argued that there are parallels between the work of George Orwell and the French philosopher Simone Weil, especially the importance they both attached to “rootedness”—that is, “a feeling of belonging in the world,” in contrast to asceticism or detachment (Quintana 2020, 105). Felicia Nimue Ackerman has emphasized the ways in which 1984 is a novel about a love affair, which addresses questions about the nature of human agency and human relationships under extreme political circumstances (Ackerman 2019). David Dwan examines Orwell’s understanding of and frequent appeals to several important moral and political terms including “equality,” “liberty,” and “justice” (Dwan 2012, 2018). Dwan holds that Orwell is “a great political educator, but less for the solutions he proffered than for the problems he embodied and the questions he allows us to ask” (Dwan 2018, 2).

Thus, although he was never a professional philosopher or member of the academy, Orwell has much to offer those interested in philosophy. An increasing number of philosophers seem to have recognized this in recent years. Although limited by his time and his prejudices, Orwell was an insightful critic of totalitarianism and many other ways in which political power can be abused. Part of his insight was the interrelationship between our political lives and other aspects of our individual and collective experiences, such as what we believe, how we communicate, and what we value. Both Orwell’s fiction and his essays provide much that is worthy of reflection for those interested in such aspects of human experience and political life.

7. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

- Down and Out in Paris and London. New York: Harcourt Publishing Company, 1933/1961.

- Burmese Days. Boston: Mariner Books, 1934/1974.

- “Shooting an Elephant.” New Writing, 1936 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/shooting-an-elephant/).

- Keep the Aspidistra Flying. New York: Harcourt Publishing Company, 1936/1956.

- The Road to Wigan Pier. New York: Harcourt Publishing Company, 1937/1958.

- Homage to Catalonia. Boston: Mariner Books, 1938/1952.

- “My Country Right or Left.” Folios of New Writing, 1940 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/my-country-right-or-left/).

- “Inside the Whale.” Published in Inside the Whale and Other Essays. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1940 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/inside-the-whale/).

- “Boys’ Weeklies.” Published in Inside the Whale and Other Essays. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1940 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/boys-weeklies/).

- “Charles Dickens.” Published in Inside the Whale and Other Essays. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1940 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/charles-dickens/).

- “Rudyard Kipling.” Horizon, 1941 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/rudyard-kipling/).

- “The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius.” Searchlight Books, 1941 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/the-lion-and-the-unicorn-socialism-and-the-english-genius/.

- “Literature and Totalitarianism.” Listener (originally broadcast on the BBC Overseas Service). June 19, 1941. (Reprinted in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Vol 2. Massachusetts: Nonpareil Books, 2007.)

- “Looking Back on the Spanish War.” New Road, 1943 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/looking-back-on-the-spanish-war/.

- “Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali.” 1944. https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/benefit-of-clergy-some-notes-on-salvador-dali/.

- “Antisemitism in Britain.” Contemporary Jewish Record, 1945 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/antisemitism-in-britain/.

- “Notes on Nationalism.” Polemic, 1945 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/notes-on-nationalism/.

- “The Sporting Spirit.” Tribune, 1945 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/the-sporting-spirit/.

- “Poetry and the Microphone.” The New Saxon Pamphlet, 1945 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/poetry-and-the-microphone/.

- “The Prevention of Literature.” Polemic, 1946 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/the-prevention-of-literature/.

- “Why I Write.” Gangrel, 1946 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/why-i-write/.

- “Politics and the English Language.” Horizon, 1946 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/politics-and-the-english-language/.

- “Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver’s Travels.” Polemic, 1946 https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/politics-vs-literature-an-examination-of-gullivers-travels/.

- “Lear, Tolstoy, and the Fool.” Polemic, 1947 (Reprinted in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Vol 4. Massachusetts: Nonpareil Books, 2002.)

- Animal Farm. New York: Signet Classics, 1945/1956.

- 1984. New York: Signet Classics, 1949/1950.

- “Such, Such Were the Joys.” Posthumously published in Partisan Review, 1952.

b. Secondary Sources

- Abramowitz, Alan I. and Steven W. Webster. (2018). “Negative Partisanship: Why Americans Dislike Parties but Behave Like Rabid Partisans.” Advances in Political Psychology 39 (1): 119-135.

- Ackerman, Felicia Nimue. (2019). “The Twentieth Century’s Most Underrated Novel.” George Orwell: His Enduring Legacy. University of New Mexico Honors College / University of New Mexico Libraries: 46-52.

- Ball, Derek. (2021). “An Invitation to Social and Political Metasemantics.” The Routledge Handbook of Social and Political Philosophy of Language, Justin and Rachel Katharine Sterken). New York and Abingdon: Routledge.