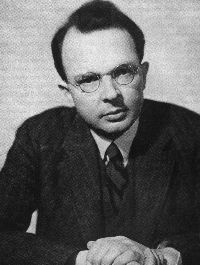

Rudolf Carnap: Modal Logic

In two works, a paper in The Journal of Symbolic Logic in 1946 and the book Meaning and Necessity in 1947, Rudolf Carnap developed a modal predicate logic containing a necessity operator N, whose semantics depends on the claim that, where α is a formula of the language, Nα represents the proposition that α is logically necessary. Carnap’s view was that Nα should be true if and only if α itself is logically valid, or, as he put it, is L-true. In the light of the criticisms of modal logic developed by W.V. Quine from 1943 on, the challenge for Carnap was how to produce a theory of validity for modal predicate logic in a way which enables an answer to be given to these criticisms. This article discusses Carnap’s motivation for developing a modal logic in the first place; and it then looks at how the modal predicate logic developed in his 1946 paper might be adapted to answer Quine’s objections. The adaptation is then compared with the way in which Carnap himself tried to answer Quine’s complaints in the 1947 book. Particular attention is paid to the problem of how to treat the meaning of formulas which contain a free individual variable in the scope of a modal operator, that is, to the problem of how to handle what Quine called the third grade of ‘modal involvement’.

In two works, a paper in The Journal of Symbolic Logic in 1946 and the book Meaning and Necessity in 1947, Rudolf Carnap developed a modal predicate logic containing a necessity operator N, whose semantics depends on the claim that, where α is a formula of the language, Nα represents the proposition that α is logically necessary. Carnap’s view was that Nα should be true if and only if α itself is logically valid, or, as he put it, is L-true. In the light of the criticisms of modal logic developed by W.V. Quine from 1943 on, the challenge for Carnap was how to produce a theory of validity for modal predicate logic in a way which enables an answer to be given to these criticisms. This article discusses Carnap’s motivation for developing a modal logic in the first place; and it then looks at how the modal predicate logic developed in his 1946 paper might be adapted to answer Quine’s objections. The adaptation is then compared with the way in which Carnap himself tried to answer Quine’s complaints in the 1947 book. Particular attention is paid to the problem of how to treat the meaning of formulas which contain a free individual variable in the scope of a modal operator, that is, to the problem of how to handle what Quine called the third grade of ‘modal involvement’.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Carnap’s Propositional Modal Logic

- Carnap’s (Non-Modal) Predicate Logic

- Carnap’s 1946 Modal Predicate Logic

- De Re Modality

- Individual Concepts

- References and Further Reading

1. Introduction

In an important article (Carnap 1946) and in a book a year later, (Carnap 1947), Rudolf Carnap articulated a system of modal logic. Carnap took himself to be doing two things; the first was to develop an account of the meaning of modal expressions; the second was to extend it to apply to what he called “modal functional logic” — that is, what we would call modal predicate logic or modal first-order logic. Carnap distinguishes between a logic or a ‘semantical system’, and a ‘calculus’, which is an axiomatic system, and states on p. 33 of 1946 that “So far, no forms of MFC [modal functional calculus] have been constructed, and the construction of such a system is our chief aim.” In fact, in the preceding issue of The Journal of Symbolic Logic, the first presentation of Ruth Barcan’s axiomatic systems of modal predicate logic had already appeared, although they contained only an axiomatic presentation. (Barcan 1946.) The principal importance of Carnap’s work is thus his attempt to produce a semantics for modal predicate logic, and it is that concern that this article will focus on.

Nevertheless, first-order logic is founded on propositional logic, and Carnap first looks at non-modal propositional logic and modal propositional logic. I shall follow Carnap in using ~ and ∨ for negation and disjunction, though I shall use ∧ in place of Carnap’s ‘.’ for conjunction. Carnap takes these as primitive together with ‘t’ which stands for an arbitrary tautologous sentence. He recognises that ∧ and t can be defined in terms of ~ and ∨, but prefers to take them as primitive because of the importance to his presentation of conjunctive normal form. Carnap adopts the standard definitions of ⊃ and ≡. I will, however, deviate from Carnap’s notation by using Greek in place of German letters for metalinguistic symbols. In place of ‘valid’ Carnap speaks of L-true, and in place of ‘unsatisfiable’, L-false. α L-implies β iff (if and only if) α ⊃ β is valid. α and β are L-equivalent iff α ≡ β is valid.

One might at this stage ask what led Carnap to develop a modal logic at all. The clue here seems to be the influence of Wittgenstein. In his philosophical autobiography Carnap writes:

For me personally, Wittgenstein was perhaps the philosopher who, besides Russell and Frege, had the greatest influence on my thinking. The most important insight I gained from his work was the conception that the truth of logical statements is based only on their logical structure and on the meaning of the terms. Logical statements are true under all conceivable circumstances; thus their truth is independent of the contingent facts of the world. On the other hand, it follows that these statements do not say anything about the world and thus have no factual content. (Carnap 1963, p. 25)

Wittgenstein’s account of logical truth depended on the view that every (cognitively meaningful) sentence has truth conditions. (Wittgenstein 1921, 4.024.) Carnap certainly appears to have taken Wittgenstein’s remark as endorsing the truth-conditional theory of meaning. (See for instance Carnap 1947 p. 9.) If all logical truths are tautologies, and all tautologies are contentless, then you don’t need metaphysics to explain (logical) necessity.

One of the features of Wittgenstein’s view was that any way the world could be is determined by a collection of particular facts, where each such fact occupies a definite position in logical space, and where the way that position is occupied is independent of the way any other position of logical space is occupied. Such a world may be described in a logically perfect language, in which each atomic formula describes how a position of logical space is occupied. So suppose that we begin with this language, and instead of asking whether it reflects the structure of the world, we ask whether it is a useful language for describing the world. From Carnap’s perspective, (Carnap 1950) one might describe it in such a way as this. Given a language £ we may ask whether £ is adequate, or perhaps merely useful, for describing the world as we experience it. It is incoherent to speak about what the world in itself is like without presupposing that one is describing it. What makes £ a Carnapian equivalent of a logically perfect language would be that each of its atomic sentences is logically independent of any other atomic sentence, and that every possible world can be described by a state-description.

2. Carnap’s Propositional Modal Logic

In (non-modal) propositional logic the truth value of any well-formed formula (wff) is determined by an assignment of truth values to the atomic sentences. For Carnap an assignment of truth values to the atomic sentences is represented by what he calls a ‘state-description’. This term, like much in what follows, is only introduced at the predicate level (1946, p. 50) but it is less confusing to present it first for the propositional case, where a state-description, which I will refer to as s, is a class consisting of atomic wff or their negations, such that for each atomic wff p, exactly one of p or ~p is in s. (Here we may think of p as a propositional variable, or as a metalinguistic variable standing for an atomic wff.) Armed with a state-description s we may determine the truth of a wff α at s in the usual way, where s ╞ α means that α is true according to s, and s ╡ α means that not s ╞ α:

If α is atomic, then s ╞ α if α ∈ s, and s ╡ α if ~α ∈ s

s ╞ ~α iff s ╡ α

s ╞ α ∨ β iff s ╞ α or s ╞ β

s ╞ α ∧ β iff s ╞ α and s ╞ β

s ╞ t

This is not the way Carnap describes it. Carnap speaks of the range of a wff (p. 50). In Carnap’s terms the truth rules would be written:

If α is atomic then the range of α is those state-descriptions s such that α ∈ s.

Where V is the set of all state-descriptions, the range of ~α is V minus the range of α, that is, it is the class of those state-descriptions which are not in the range of α.

The range of α ∨ β is the range of α ∪ the range of β, that is, the class of state-descriptions which are either in the range of α or the range of β.

The range of α ∧ β is the range of α ∩ the range of β, that is, the class of state-descriptions which are in both the range of α and the range of β.

The range of t is V.

It should I hope be easy to see, first that Carnap’s way of putting things is equivalent to my use of s ╞ α, and second that these are in turn equivalent to the standard definitions of validity in terms of assignments of truth values.

By a ‘calculus’ Carnap means an axiomatic system, and he uses ‘PC’ to indicate any axiomatic system which is closed under modus ponens (the ‘rule of implication’, p. 38) and contains “‘t’ and all sentences formed by substitution from Bernays’s four axioms [See Hilbert and Ackermann, 1950, p. 28f] of the propositional calculus”. (loc cit.) Carnap notes that the soundness of this axiom system may be established in the usual way, and then shows how the possibility of reduction to conjunctive normal form (a method which Carnap, p. 38, calls P-reduction) may be used to prove completeness.

Modal logic is obtained by the addition of the sentential operator N. Carnap notes that N is equivalent to Lewis’s ~◊~. (Note that the □ symbol was not used by Lewis, but was invented by F.B. Fitch in 1945, and first appeared in print in Barcan 1946. It was not then known to Carnap.) Carnap tells us early in his article that “the guiding idea in our construction of systems of modal logic is this: a proposition p is logically necessary if and only if a sentence expressing p is logically true.” When this is turned into a definition in terms of truth in a state-description we get the following:

s ╞ Nα iff sʹ ╞ α for every state-description sʹ.

This is because L-truth, or validity, means truth in every state-description. I shall refer to validity when N is interpreted in this way, as Carnap-validity, or C-validity. This account enables Carnap to address what was an important question at the time — what is the correct system of modal logic? While Carnap is clear that different systems of modal logic can reflect different views of the meaning of the necessity operators he is equally clear that, as he understands it, principles like Np ⊃ NNp and ~Np ⊃ N~Np are valid. It is easy to see that the validity of both these formulae follows easily from Carnap’s semantics for N. From this it is a short step to establishing that Carnap’s modal logic includes the principles of Lewis’s system S5, provided one takes the atomic wff to be propositional variables. However, we immediately run into a problem. Suppose that p is an atomic wff. Then there will be a state-description sʹ such that ~p ∈ sʹ. And this means that for every state-description s, s ╡ Np, and so s ╞ ~Np. But this means that ~Np will be L-true. One can certainly have a system of modal logic in which this is so. An axiomatic basis and a completeness proof for the logic of C-validity occurs in Thomason 1973. (For comments on this feature of C-validity see also Makinson 1966 and Schurz 2001.) However, Carnap is clear that his system is equivalent to S5 (footnote 8, p. 41, and on p. 46.); and ~Np is not a theorem of S5. Further, the completeness theorem that Carnap proves, using normal forms, is a completeness proof for S5, based on Wajsberg 1933.

How then should this problem be addressed? Part of the answer is to look at Carnap’s attitude to propositional variables:

We here make use of ‘p’, ‘q’, and so forth, as auxiliary variables; that is to say they are merely used (following Quine) for the description of certain forms of sentences. (1946, p.41)

Quine 1934 suggests that the theorems of logic are always schemata. If so then we can define a wff α as what we might call QC-valid (Quine/Carnap valid) iff every substitution instance of α is C-valid. Wffs which are QC-valid are precisely the theorems of S5.

3. Carnap’s (Non-Modal) Predicate Logic

In presenting Carnap’s 1946 predicate logic (or as he prefers to call it ‘functional logic’, FL or FC depending on whether we are considering it semantically or axiomatically) I shall use ∀x in place of (x), and ∃x in place of (∃x). FL contains a denumerable infinity of individual constants, which I will often refer to simply as ‘constants’. Carnap uses the term ‘matrix’ for wff, and the term ‘sentence’ for closed wff, that is wff with no free variables. A state-description is as for propositional logic in containing only atomic sentences or their negations. Each of these will be a wff of the form Pa1…an or ~Pa1…an, where P is an n-place predicate and a1,…, an are n individual constants, not necessarily distinct.

To define truth in such a state-description Carnap proceeds a little differently from what is now common. In place of relativising the truth of an open formula to an assignment to the variables of individuals from a domain, Carnap assumes that every individual is denoted by one and only one individual constant, and he only defines truth for sentences. If s is any state-description, and α and β are any sentences, the rules for propositional modal logic can be extended by adding the following:

s ╞ Pa1…an if Pa1…an ∈ s and s ╡ Pa1…an if ~Pa1…an ∈ s

s ╞ a = b iff a and b are the same constant

s ╞ ∀xα iff s ╞ α[a/x] for every constant a, where [α/x] is α with a replacing every free x.

Carnap produces the following axiomatic basis for first-order predicate logic, which he calls ‘FC’. In place of Carnap’s ( ) to indicate the universal closure of a wff, I shall use ∀, so that Carnap’s D8-1a (1946, p. 52) can be written as:

PC ∀α where α is a PC-tautology

and so on. Carnap refers to axioms as ‘primitive sentences’ and in addition to PC, using more current names, we have:

∀⊃ ∀(∀x(α ⊃ β) ⊃ (∀xα ⊃ ∀xβ))

VQ ∀(α ⊃ ∀xα), where x is not free in α.

∀1a ∀(∀x ⊃ α[y/x]), where α[y/x] is just like α except in having y in place of free x, where y is any variable for which x is free

∀1b ∀(∀x ⊃ α[b/x]), where α[b/x] is just like α except in having b in place of free x, where b is any constant

I1 ∀x x = x

I2 ∀(x = y ⊃ (α ⊃ β)), where α and β are alike except that α has free x in 0 or more places where β has free y.

I3 a ≠ b where a and b are different constants.

The only transformation rule is modus ponens:

MP ├ α, ├ α ⊃ β therefore ├ β

The only thing non-standard here, except perhaps for the restriction of theorems to closed wffs, is I3, which ensures that all state-descriptions are infinite, and, as Carnap points out on p. 53, validates ∃x∃y x ≠ y. It is possible to prove the completeness of this axiomatic system with respect to Carnap’s semantics.

4. Carnap’s 1946 Modal Predicate Logic

Perhaps the most important issue in Carnap’s modal logic is its connection with the criticisms of W.V. Quine. These criticisms were well known to Carnap who cites Quine 1943. Some years later, in Quine 1953b, Quine distinguishes three grades of what he calls ‘modal involvement’. The first grade he regards as innocuous. It is no more than the metalinguistic attribution of validity to a formula of non-modal logic. In the second grade we say that where α is any sentence then Nα is true iff α itself is valid — or logically true. On pp. 166-169 Quine argues that while such a procedure is possible it is unilluminating and misleading. The third grade applies to modal predicate logic, and allows free individual variables to occur in the scope of modal operators. It is this grade that Quine finds objectionable. One of the points at issue between Quine and Carnap arises when we introduce what are called definite descriptions into the language. Much of Carnap’s discussion in his other works — see especially Carnap 1947 — elevates descriptions to a central role, but in the 1946 paper these are not involved.

The extension of Carnap’s semantics to modal logic is exactly as in the propositional case:

s ╞ Nα iff sʹ ╞ α for every state-description sʹ.

As before, a wff can be called C-valid iff it is true in every state-description, when ╞ satisfies the principle just stated. As in the propositional case if α is S5-valid then α is C-valid. However, also as in the propositional case, (quantified) S5 is not complete for C-validity. This is because, where Pa is an atomic wff, ~NPa is C-valid even though it is not a theorem of S5 — and similarly with any atomic wff. Unlike the propositional case it seems that this is a feature which Carnap welcomed in the predicate case, since he introduces some non-standard axioms.

The first set of axioms all form part of a standard basis for S5. They are as follows (p. 54, but with current names and notation):

LPCN Where α is one of the LPC axioms PC-I3 then both α and Nα are axioms of MFC.

K N∀(N(α ⊃ β) ⊃ (Nα ⊃ Nβ))

T ∀(Nα ⊃ α)

5 N∀(Nα ∨ N~Nα)

BFC N∀(N∀xα ⊃ ∀xNα)

BF N∀(∀xNα ⊃ N∀xα)

The non-standard axioms, which show that he is attempting to axiomatise C-validity, are what Carnap calls ‘Assimilation’, ‘Variation and Generalization’ and ‘Substitution for Predicates’. (Carnap 1946, p. 54f.) In our notation these can be expressed as follows:

Ass N∀x∀y∀z1…∀zn((x ≠ z1 ∧ … ∧ x ≠ zn) ⊃ (Nα ⊃ N α[y/x])), where α contains no free variables other than x, y, z1,…, zn, and no constants and no occurrences of =.

VG N∀x∀y∀z1…∀zn((x ≠ z1 ∧ … ∧ x ≠ zn ∧ y ≠ z1 ∧ … ∧ y ≠ zn) ⊃ (Nα ⊃ N α[y/x]), where α contains no free variables other than x, y, z1,…, zn, and no constants.

SP N∀(Nα ⊃ Nβ), where β is obtained from α by uniform substitution of a complex expression for a predicate.

None of these axiom schemata is easy to process, but it is not difficult to see what the simplest instances would look like. A very simple instance, which is of both Ass and VG is

AssP N∀x∀y∀z(x ≠ z ⊃ (NPxyz ⊃ NPyyz))

To establish the validity of AssP it is sufficient to show that if a and c are distinct constants then NPabc ⊃ NPbbc is valid. This is trivially so, since there is some s such that s ╡ Pabc, and therefore for every s, s ╡ NPabc, and so, for every s, s ╞ NPabc ⊃ Pbbc. More telling is the case of SP. Let P be a one-place predicate and consider

SPP N∀x(NPx ⊃ N(Px ∧ ~Px))

In this case α is Px, while β is Px ∧ ~Px, so that, in Carnap’s words, β ‘is formed from α by replacing every atomic matrix containing P by the current substitution form of β’. That is, where β is Px ∧ ~Px, it replaces α’s Px. If α had been more complex and contained Py as well as Px, then the replacement would have given Py ∧ ~ Py, and so on, where care needs to be taken to prevent any free variable being bound as a result of the replacement. In this case we have ├ ~N(Pa ∧ ~ Pa), and so ├ ~NPa.

In fact, although Carnap appears to have it in mind to axiomatise C-validity, it is easy to see that the predicate version is not recursively axiomatisable. For, where α is any LPC wff, α is not LPC-valid iff ~Nα is C-valid, and so, if C-validity were axiomatisable then LPC would be decidable. There is a hint on p. 57 that Carnap may have recognised this. He is certainly aware that the kind of reduction to normal form, with which he achieves the completeness of propositional S5, is unavailable in the predicate case, since it would lead to the decidability of LPC.

5. De Re Modality

What then can be said on the basis of Carnap 1946 to answer Quine’s complaints about modal predicate logic? Quine illustrates the problem in Quine 1943, pp. 119-121, and repeats versions of his argument many times, most famously perhaps in Quine 1953a, 1953b and 1960. The example goes like this:

(1) 9 is necessarily greater than 7

(2) The number of planets = 9

therefore

(3) The number of planets is necessarily greater than 7.

Carnap 1946 does not introduce definite descriptions into the language, so I shall present the argument in a formalisation which only uses the resources found there. I shall also simplify the discussion by using the predicate O, where Ox means ‘x is odd’, rather than the complex predicate ‘is greater than 7’. This will avoid reference to ‘7’, which is of no relevance to Quine’s argument. P means ‘is the number of the planets’, so that Px means ‘there are x-many planets’. With this in mind I take ‘9’ to be an individual constant, and use O and P to express (1) and (2) by

(4) NO9

(5) ∃x(Px ∧ x = 9)

One could account for (4) by adding O9 as a meaning postulate in the sense of Carnap 1952, which would restrict the allowable state-descriptions to those which contain O9, though from some remarks on p. 201 of Carnap 1947 it seems that Carnap might have regarded both O and 9 as complex expressions defined by the resources of the Frege/Russell account of the natural numbers and their arithmetical properties. It also seems that he might have treated the numbers as higher-order entities referred to by higher-order expressions. If so then the necessity of arithmetical truths like (4) would derive from their analysis into logical truths. In my exposition I shall take the numerals as individual constants, and assume somehow that O9 is a logical truth, true in every state-description, and that therefore (4) is true.

In this formalisation I am ignoring the claim that the description ‘the number of the planets’ is intended to claim that there is only one such number. So much for the premises. But what about the conclusion? The problem is where to put the N. There are at least three possibilities:

(6) N∃x(Px ∧ Ox)

(7) ∃xN(Px ∧ Ox)

(8) ∃x(Px ∧ NOx)

It is not difficult to show that (6) and (7) do not follow from (4) and (5). In contrast to (6) and (7), (8) does follow from (4) and (5), but there is no problem here, since (8) says that there is a necessarily odd number which is such that there happen to be that many planets. And this is true, because 9 is necessarily odd, and there are 9 planets. All of this should make clear how the phenomenon which upset Quine can be presented in the formal language of the 1946 article. Quine of course claims not to make sense of quantifying in. (See for instance the comments on Smullyan 1948 in Quine 1969, p. 338.)

6. Individual Concepts

Even if something like what has just been said might be thought to enable Carnap to answer Quine’s complaints about de re modality, it seems clear that Carnap had not availed himself of it in the 1947 book, and I shall now look at the modal logic presented in Carnap 1947. On p. 193f Carnap cites the argument (1)(2)(3) from Quine 1943 discussed above. He does not appear to recognise any potential ambiguity in the conclusion, and characterises (3) as false. Carnap doesn’t consider (8), and on p. 194 simply says:

“we obtain the false statement [(3)]”

In Carnap’s view the problem with Quine’s argument is that it assumes an unrestricted version of what is sometimes called ‘Leibniz’ Law’:

I2 ∀x∀y(x = y ⊃ (α ⊃ β)), where α and β differ only in that α has free x in 0 or more places where β has free y.

In the 1946 paper this law holds in full generality, as does a consequence of it which asserts the necessity of true identities.

LI ∀x∀y(x = y ⊃ Nx = y)

For suppose LI fails. Then there would have to be a state-description ss in which for some constants a and b, s ╞ a = b but s ╡ Na = b. So there is a state-description sʹ such that sʹ ╡ a = b, but then, a and b are different constants, and so, s ╡ a = b, which gives a contradiction.

In the 1947 book Carnap holds that I2 must be restricted so that neither x nor y occur free in the scope of a modal operator. In particular the following would be ruled out as an allowable instance of I2:

(1) x = y ⊃ (NOx ⊃ NOy)

In order to explain how this failure comes about, and solve the problems posed by co-referring singular terms, Carnap modifies the semantics of the 1946 paper. The principal difference from the modal logic of the 1946 paper, as Carnap tells us on p. 183, is that the domain of quantification for individual variables now consists of individual concepts, where an individual concept i is a function from state-descriptions to individual constants. Where s is a state-description, let is denote the constant which is the value of the function i for the state-description s. Carnap is clear that the quantifiers range over all individual concepts, not just those expressible in the language.

Using this semantics it is easy to see how (9) can fail. For let x have as its value the individual concept i, which is the function such that is is 9 for every state-description s, while the value of y is the function j such that, in any state-description s, js is the individual which is the number of the planets in s, that is, js is the (unique) constant a such that Pa is in s. (Assume that in each state-description there is a unique number, possibly 0, which satisfies P.) Assume that x = y is true in any state-description s iff, where i is the individual concept which is the value of x, and j is the individual concept which is the value of y, then is is the same individual constant as js. In the present example it happens that when s is the state-description which represents the actual world, is and js are indeed the same, for in s there are nine planets, making x = y true at s. Now NOx will be true if Ox is true in every state-description sʹ, which is to say if isʹ satisfies O in every sʹ. Since isʹ is 9 in every state-description then isʹ does satisfy O in every sʹ, and so NOx is true at s. But suppose sʹ represents a situation in which there are six planets. Then jsʹ will be 6 and so Oy will be false in sʹ, and for that reason NOy will be false in s, thus falsifying (9). (It is also easy to see that LI is not valid, since it is easy to have is = js even though i ≠ j.)

The difference between the modal semantics of Carnap 1946 and Carnap 1947 is that in the former the only individuals are the genuine individuals, represented by the constants of the language ℒ. In the proof of the invalidity of (9) it is essential that the semantics of identity require that when x is assigned an individual concept i and y is assigned an individual concept j that x = y be true at a state-description s iff is and js are the same individual. And now we come to Quine’s complaint (Quine 1953a, p. 152f). It is that Carnap replaces the domain of things as the range of the quantifiers with a domain of individual concepts. Quine then points out that the very same paradoxes arise again at the level of individual concepts. Thus for instance it might be that the individual concept which represents the number of planets in each state-description is identical with the first individual concept introduced on p. 193 of Meaning and Necessity. Carnap is alive to Quine’s criticism that ordinary individuals have been replaced in his ontology by individual concepts. In essence Carnap’s reply to Quine on pp. 198- 200 of Carnap 1947 is that if we restrict ourselves to purely extensional contexts then the entities which enter into the semantics are precisely the same entities as are the extensions of the intensions involved. What this amounts to is that although the domain of quantification consists of individual concepts, the arguments of the predicates are only the genuine individuals. For suppose, as Quine appears to have in mind, we permit predicates which apply to individual concepts. Then suppose that i and j are distinct individual concepts. Let P be a predicate which can apply to individual concepts, and let s be a state-description in which P applies to i but not to j but in which is and js are the same individual. We now have two options depending on how = is to be understood. If we take x = y to be true in s when is and js are the same individual then if x is assigned i and y is assigned j we would have that x = y and Px are both true in s, but Py is not. So that even the simplest instance of I2

I2P x = y ⊃ (Px ⊃ Py)

fails, and here there are no modal operators involved. The second option is to treat = as expressing a genuine identity. That is to say x = y is true only when the individual concept assigned to x is the same individual concept as the one assigned to y. In the example I have been discussing, since i and j are distinct individual concepts if i is assigned to x and j to y, then x = y will be false. But on this option the full version of I2 becomes valid even when α and β contain modal operators. This is just another version of Quine’s complaint that if an operator expresses identity then the terms of a true identity formula must be interchangeable in all contexts. Presumably Carnap thought that the use of individual concepts could address these worries. The present article makes no claims on whether or not an acceptable treatment of individual concepts is desirable, and if it is whether one can be developed.

7. References and Further Reading

This list contains all items referred to in the text, together with some other articles relevant to Carnap’s modal logic.

- Barcan, (Marcus) R.C., 1946, A functional calculus of first order based on strict implication. The Journal of Symbolic Logic, 11, 1–16.

- Burgess, J.P., 1999, Which modal logic is the right one? Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 40, 81–93.

- Carnap, R., 1937, The Logical Syntax of Language, London, Kegan Paul, Trench Truber.

- Carnap, R., 1946, Modalities and quantification. The Journal of Symbolic Logic, 11, 33–64.

- Carnap, R., 1947, Meaning and Necessity, Chicago, University of Chicago Press (Second edition 1956, references are to the second edition.).

- Carnap, R., 1950, Empiricism, semantics and ontology. Revue Intern de Phil. 4, pp. 20–40 (Reprinted in the second edition of Carnap 1947, pp. 2052–2221. Page references are to this reprint.).

- Carnap, R., 1952, Meaning postulates. Philosophical Studies, 3, pp. 65–73. (Reprinted in the second edition of Carnap 1947, pp. 222–229. Page references are to this reprint.)

- Carnap, R., 1963, The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap, ed P.A. Schilpp, La Salle, Ill., Open Court, pp. 3–84.

- Church, A., 1973, A revised formulation of the logic of sense and denotation (part I). Noũs, 7, pp. 24–33.

- Cocchiarella, N.B., 1975a, On the primary and secondary semantics of logical necessity. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 4, pp. 13–27..

- Cocchiarella, N.B.,1975b, Logical atomism, nominalism, and modal logic. Synthese, 31, pp. 23−67.

- Cresswell, M.J., 2013, Carnap and McKinsey: Topics in the pre–history of possible worlds semantics. Proceedings of the 12th Asian Logic Conference, J. Brendle, R. Downey, R. Goldblatt and B. Kim (eds), World Scientific, pp. 53-75.

- Garson, J.W., 1980, Quantification in modal logic. Handbook of Philosophical Logic, ed. D.M. Gabbay and F. Guenthner, Dordrecht, Reidel, Vol. II, Ch. 5, 249-307

- Gottlob, G., 1999, Remarks on a Carnapian extension of S5. In J. Wolenski, E. Köhler (eds.), Alfred Tarski and the Vienna Circle, Kluwer, Dordrecht, 243−259.

- Hilbert, D., and W. Ackermann, 1950, Mathematical Logic, New York, Chelsea Publishing Co., (Translation of Grundzüge der Theoretischen Logik.).

- Hughes, G.E., and M.J. Cresswell, 1996, A New Introduction to Modal Logic, London, Routledge.

- Lewis, C.I., and C.H. Langford, 1932, Symbolic Logic, New York, Dover publications.

- Makinson, D., 1966, How meaningful are modal operators? Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 44, 331−337.

- Quine, W.V.O., 1934, Ontological remarks on the propositional calculus. Mind, 433, pp. 473– 476.

- Quine, W.V.O., 1943, Notes on existence and necessity, The Journal of Philosophy, Vol 40, pp. 113-127.

- Quine, W.V.O., 1953a, Reference and modality. From a Logical Point of View, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, second edition 1961, pp. 139–59.

- Quine, W.V.O., 1953b, Three grades of modal involvement, The Ways of Paradox, Cambridge Mass., Harvard University Press, 1976, pp. 158–176.

- Quine, W.V.O., 1960, Word and Object, Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press.

- Quine, W.V.O., 1969, Reply to Sellars. Words and Objections, (ed D. Davidson and K.J.J. Hintikka), Dordrecht, Reidel, 1969, pp. 337–340.

- Schurz, G., 2001, Carnap’s modal logic. In W. Stelzner and M. Stockler (eds.), Zwischen traditioneller und moderner Logik. Paderborn, Mentis, pp. 365–380.

- Smullyan, A.F., 1948, Modality and description. The Journal of Symbolic Logic, 13, 31–7.

- Thomason, S. K.,1973, New Representation of S5. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 14, 281−284.

- Wajsberg, M., 1933, Ein erweiteter Klassenkalkül. Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik, Vol. 40, 113–26.

- Wittgenstein, L., 1921, Tractatus Logic-Philosophicus. (Translated by D.F.Pears and B.F.McGinness), 2nd printing 1963. London, Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Author Information

M. J. Cresswell

Email: max.cresswell@msor.vuw.ac.nz

Victoria University of Wellington

New Zealand