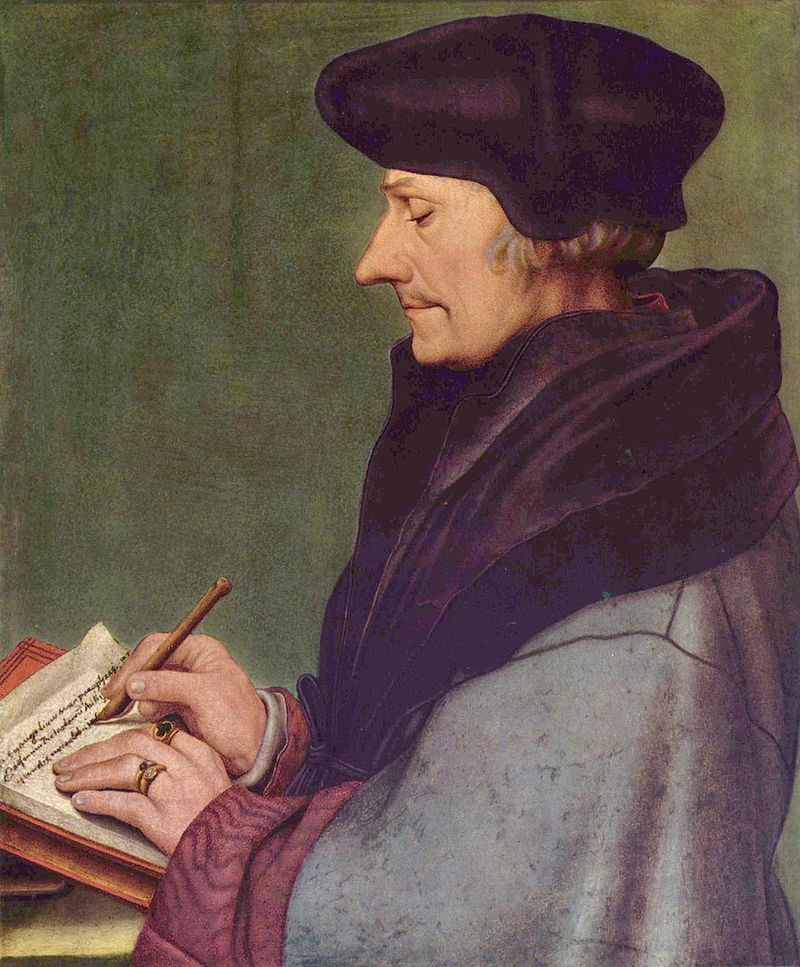

Desiderius Erasmus (1468?—1536)

Desiderius Erasmus was one of the leading activists and thinkers of the European Renaissance. His main activity was to write letters to the leading statesmen, humanists, printers, and theologians of the first three and a half decades of the sixteenth century. Erasmus was an indefatigable correspondent, controversialist, self-publicist, satirist, translator, commentator, editor, and provocateur of Renaissance culture. He was perhaps above all renowned and repudiated for his work on the Christian New Testament. He was not a systematic thinker, and he did not found a system or school of philosophy. In fact, his profound contempt for the scholastic philosophers of the Middle Ages and Renaissance puts him at odds with the institution of philosophy. Perhaps Erasmus’ most important role in the history of philosophy is to have challenged and expanded the disciplinary boundaries of the field. He did so by propounding his philosophy of Christ, which displays some affinities for prior traditions including Platonism and Epicureanism, but which depends primarily on the understanding that philosophy is not an exclusive university discipline, but rather a moral obligation incumbent upon all believers. In this context he founded an ethics of speech to guide himself and others to what he regarded as the true love of wisdom.

Desiderius Erasmus was one of the leading activists and thinkers of the European Renaissance. His main activity was to write letters to the leading statesmen, humanists, printers, and theologians of the first three and a half decades of the sixteenth century. Erasmus was an indefatigable correspondent, controversialist, self-publicist, satirist, translator, commentator, editor, and provocateur of Renaissance culture. He was perhaps above all renowned and repudiated for his work on the Christian New Testament. He was not a systematic thinker, and he did not found a system or school of philosophy. In fact, his profound contempt for the scholastic philosophers of the Middle Ages and Renaissance puts him at odds with the institution of philosophy. Perhaps Erasmus’ most important role in the history of philosophy is to have challenged and expanded the disciplinary boundaries of the field. He did so by propounding his philosophy of Christ, which displays some affinities for prior traditions including Platonism and Epicureanism, but which depends primarily on the understanding that philosophy is not an exclusive university discipline, but rather a moral obligation incumbent upon all believers. In this context he founded an ethics of speech to guide himself and others to what he regarded as the true love of wisdom.

Table of Contents

- Life and Works

- Erasmus and Philosophy

- The Word

- A Controversial Legacy

- References and Further Reading

1. Life and Works

Erasmus was born in the city of Rotterdam in the late 1460s and was educated by the Brethren of the Common Life, first at Deventer and then at s’Hertogenbosch. Orphaned at an early age, he took monastic vows and entered the Augustinian monastery at Steyn in 1486. In 1492 he was ordained a priest and in 1493 he entered the service of Hendrik van Bergen, the Bishop of Cambrai, who had just been named chancellor of the order of the Golden Fleece by the court of Burgundy. Service as secretary to an ambitious prelate delivered Erasmus from the tedium of monastic life and offered the prospect of travel and advancement. When the bishop’s career stalled, Erasmus left to study theology at the University of Paris in 1495, where he remained long enough to contract a lifelong aversion to the professional study of theology and its addiction to dialectic.

It was in Paris that Erasmus became attached to his first important patron, William Blount, Lord Mountjoy, whom he accompanied to England as tutor in 1499. This first English sojourn, though brief, proved crucial to Erasmus’ subsequent career since it was during this visit that he became acquainted with Thomas More and John Colet, founder of St. Paul’s School in London. Erasmus returned to Paris in 1500 to publish his first collection of proverbs, the Adagiorum Collectanea, whose dedicatory epistle, addressed to Mountjoy, remains a crucial statement of Erasmian poetics. After further itineracy in France and the Low Countries, he returned to England, where he was the guest of Thomas More, with whom he collaborated on a translation of selected dialogues by Lucian of Samosata. He embarked in 1506 on a long awaited voyage to Italy. In Venice,Erasmus worked with the humanist printer Aldus Manutius to publishthe first great collection of adages, the Adagiorum Chiliades in 1508. It was completed with the generous collaboration of numerous Italian humanists, as gratefully recorded in the adage Festina lente. From Italy, he went back to England, where he stayed long enough to compose the Praise of Folly (1511) and several educational writings including the De ratione studii of 1511, a preliminary version of his manual on letter writing De conscribendis epistolis, which was not published until 1522, and the completed version of De copia or On abundance in style (1512).

Having returned to the European continent in 1514, Erasmus began his association with the Swiss printer Johann Froben, for whom he prepared an expanded version of the adages in 1515. The following year brought forth from the Froben press (of Basel, Switzerland) the two works which Erasmus regarded as the twin masterpieces of his career. First came the Novum Instrumentum consisting of the Greek text and Erasmus’ own Latin translation of the New Testament, with Erasmus’ annotations keyed to the Latin text of the Vulgate. Next came, in nine volumes, the complete works of Saint Jerome, including four volumes of Jerome’s letters, edited by Erasmus himself and dedicated to William Warham, the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the beginning of Volume One stands Erasmus’ Life of Jerome. In 1517 Erasmus took up residence in Louvain. There he quickly became embroiled in a controversy with the faculty of theology at the university, over the role of the three languages–Greek, Latin, and Hebrew–in the study of theology. This was upon the immediate occasion of the foundation of a trilingual college in Louvain from the bequest of Erasmus’ friend Jérôme de Busleyden. Erasmus championed humanist theology, based on study of ancient languages, against the reactionary stance of the Louvain theologians who were intent on preserving their professional prerogatives. At the same time Erasmus launched another important scholarly venture, the Paraphrases on the New Testament, starting with the Epistle to the Romans in 1517.

In 1521, Erasmus moved to Basel where he collaborated closely with the Froben press on a succession of expanded editions of the Adages while continuing the Paraphrases on the New Testament. As the decade wore on Erasmus became involved in a reluctant and debilitating quarrel with Martin Luther over the competing doctrines of free will and predestination. Erasmus published his Diatribe on Free Will in 1524, to which Luther answered in 1525 with his treatise The Enslaved Will, which elicited from Erasmus the Hyperaspistes or Shieldbearer issued in two parts in 1526 and 1527. From this quarrel, Richard Popkin dated the advent of modern skepticism in his authoritative History of Scepticism. Having alienated many Catholic clerics with his trenchant criticism of Church hierarchy and Catholic devotion, Erasmus refused to join the Protestant reformers and found himself increasingly isolated as an advocate of Church unity through conciliation rather than persecution or reform. Towards the end of the decade, in the wake of the 1527 Sack of Rome, the Spanish Inquisition convened a conference in the city of Valladolid in order to deliberate on suspect passages in Erasmus’ work and to determine whether his books should be banned in Spain. Though the plague interrupted the Conference of Valladolid in August 1527 before it could reach a verdict, this did not deter Erasmus from composing a lengthy Apology addressed to the Spanish monks who had challenged his orthodoxy. The following year, 1528, Erasmus published his dialogue Ciceronianus (1528), attacking the pagan instincts of Cicero’s strictest humanist disciples, thereby ensuring himself continued notoriety among European men of letters. Erasmus finally left Basel in 1529 when the city officially declared its allegiance to the Reform, and took up residence in the Catholic city of Freiburg. In the few moments of leisure left to him by his interminable polemics and his voluminous correspondence, Erasmus composed his last masterpiece, his treatise on the rhetoric of preaching, entitled Ecclesiastes, which he completed and published in 1535. Erasmus’ travels came to an end on July 12, 1536 in Basel, where he had stopped on his way back to the Low Countries.

2. Erasmus and Philosophy

Scholarship has long recognized Erasmus’ problematic standing in the history of philosophy. For Craig Thompson, Erasmus cannot be called philosopher in the technical sense, since he disdained formal logic and metaphysics and cared only for moral philosophy. Similarly, John Monfasani reminds us that Erasmus never claimed to be a philosopher, was not trained as a philosopher, and wrote no explicit works of philosophy, although he repeatedly engaged in controversies that crossed the boundary from philosophy to theology. His relation to philosophy bears further scrutiny.

a. Humanism

To evaluate Erasmus’ relationship to philosophy, we have to understand his identity as a humanist. One of his earliest works, begun in his monastic youth, though not published until 1520, was the Antibarbari. It proposes a defense of the humanities, then essentially the study of classical languages and literature, against detractors who were scorned as barbarians. One of the key themes of the work is the vital role of classical culture in a Christian society, and this theme entails a redefinition of philosophy, in contrast to the prevailing university discipline of philosophy. Everything of value in pagan culture, insists the main interlocutor in the dialogue, was intended by Christ to enrich Christian society, and this includes philosophy, since Christ himself was “the very father of philosophy” (CWE 23:102; ASD I-1:121). The philosophy he fathered is the philosophy that Erasmus professed throughout his life and work, the philosophia Christi. This philosophy is not so much a set of dogmas as it is a way of life or an ethical commitment.

b. Platonism

One of Erasmus’ first published works and one of his most enduringly popular ones was the Enchiridion militis Christiani, or Manual of the Christian Soldier, of 1503. Written to an anonymous friend at court who had asked Erasmus to compose for him a guide to life, or ratio vivendi, that would lead him to a state of mind worthy of Christ. The Enchiridion gained immediate notoriety for its repudiation of monasticism and its insistence that true piety consists not in outward ceremonies but inward conversion. In the course of events, these themes would become associated with the Protestant Reformation. The Enchiridion espouses a philosophy of duality, the duality of body and soul, letter and spirit, that is explicitly modeled on Platonism. The author deplores the fact that professional philosophers, obsessed with Aristotle, have banished Platonists and Pythagoreans from the classroom, and he cites approvingly St. Augustine’s preference of Plato over Aristotle. Of the two classical philosophers, Plato’s doctrines are closer to Christianity and his allegorical style is better suited to the exposition of scripture.

When the Enchiridion defines philosophy, it invokes a Socratic precedent. Socrates, in Plato’s dialogue Phaedo, said that philosophy was nothing other than meditation on death because it gradually alienates us from the material and corporeal concerns of life. Philosophy takes us out of the world, the mundus, and into Christ. This withdrawal from the world is not just for religious professionals, such as priests or monks, but for everyone in every walk of life. Philosophy is a spiritual state rather than a professional identity.

c. Philosopher Kings

Among the many Platonic topoi that appealed to Erasmus, none feature more consistently in his work than the ideal of the philosopher king, first introduced in Plato’s Republic. Often this serves as an epideictic topos, as when Erasmus hails Charles V’s brother Ferdinand as a philosopher king (in the conclusion to his treatise on the Christian concord De sarcienda ecclesiae concordia) (ASD V-3:313), or when he similarly acclaims King Sigismund of Poland in a letter to a Polish correspondent (Ep. 2533). Yet, the topic also sponsors some provocative thinking on philosophy. When Erasmus published his Education of a Christian Prince in 1516, he dedicated the treatise to Prince Charles, King of Spain, who was soon to succeed his grandfather Maximilian as Holy Roman Emperor, under the title Charles V. The dedicatory epistle evokes the familiar Platonic claim that no republic will be fortunate until philosophers are kings or kings embrace philosophy. By philosophy, Erasmus understands not the Aristotelian physics and metaphysics that dominated the university curriculum, but rather that kind of philosophy that frees our mind from errors and vices, and demonstrates correct government on the model of the eternal power. This model, or aeterni numinis exemplar, (ASD IV-1:133) is Christ, and the new philosopher king is a disciple of Christ.

Erasmus returns to the philosopher king in the text of his treatise on political philosophy when he again qualifies the meaning of “philosophy.” To be a philosopher does not mean to be skilled at dialectic or physics, but rather to prefer truth to illusion. In sum, to be a philosopher is the same as to be a Christian: “idem esse philosophum et esse Christianum” (ASD IV-1:145). This is the most compact and emphatic statement of Erasmus’s philosophy of Christ. His most mature and complete statement can be found in the Paraclesis, one of the forewords or prefaces he composed for his edition of the New Testament, also from 1516. In its opening lines, the Paraclesis exhorts all mortals to the holiest and most salubrious study of Christian philosophy, insisting that this type of wisdom can be learned from fewer books and with less effort than the arcane doctrines of Aristotle. The philosophy of Christ is a straight road open to all who are endowed with pure and simple faith, and not an exclusive discipline reserved for specialists. In this context, Erasmus adds a controversial endorsement of vernacular translations of the Bible, so that everyone can share in the message of Christ.

d. Paradox

As we have seen, Erasmus often defines philosophy in the negative: his philosophy is not what people conventionally understand as philosophy. He repudiates conventional philosophy as too contentious, too belligerent and dogmatic. He prefers instead to experiment with a non-assertive form of philosophy that relies on paradox and on the neutralizing force of opposing arguments. His best known experiment in extended paradox, and his best claim to permanence in school curriculum, is the Praise of Folly, first published in Paris in 1511, and accompanied in subsequent editions by a commentary attributed to Gerhard Lister but thought to have been dictated by Erasmus himself. Folly, or Moria, delivers her own encomium, proudly invoking the inspiration of the ancient Greek sophists and seemingly disqualifying her every claim, except perhaps for her satire of the clergy and the learned professions; this is followed by a deceptively earnest exposition of Pauline spirituality, where we detect the same stylistic devices and profusion of proverbs as in the rest of the text. Erasmus labeled his text a declamation, in the sense of a thesis meant to provoke a counter-thesis rather than to assert a dogma. After all, the speaker is Folly, a notoriously unreliable authority on all matters secular and religious and from whom it is no dishonor to differ in views. Rather, we should be ashamed to agree with her. By resorting to this subterfuge, rather than positively asserting his beliefs in his own name, Erasmus was able to intervene in a number of intellectual, political, and spiritual debates in contemporary Christendom without affirming or denying anything.

Though voiced by Folly herself, the critique of church and clergy contained in the Praise of Folly provoked a bitter resentment among doctors of theology, as we know from correspondence between Erasmus and the Louvain theologian Martin Dorp. In a letter dated September 1514, Dorp testifies to the hostile reaction of the professional theologians to the Moriae Encomium and their apprehension of Erasmus’ new project to edit the New Testament, of which word had already begun to circulate largely due to Erasmus’ own public relations campaign. Erasmus’ response to Dorp in epistle 337 recapitulates many of the themes of his life-long tirade against scholasticism. One of the key themes here is the stark contrast drawn between the recent style of theology exemplified by the scholastics, and the old style of theology associated with the Church Fathers, many of whose works Erasmus edited. The passage from old to new has hardly been an improvement. The upstarts or recentiores are so engrossed in their factional disputes and dialectical quibbles that they do not have time to read the Bible. Erasmus makes his case most succinctly when he asks, “What does Aristotle have to do with Christ?” In effect, he accuses the schoolmen of idolatry in their substitution of pagan for Christian authority. The letter to Dorp, which was revised for publication with the Praise of Folly beginning with the Basel edition of 1516, offers a powerful and insidious repudiation of university theology and philosophy.

e. Epicureanism

Erasmus thus had little enthusiasm for the various philosophic orthodoxies prevailing among the ancients or the moderns. However, fairly late in life, and only belatedly acknowledged by criticism, he did turn in sympathy to one of the Hellenistic schools of philosophy, namely Epicureanism. Erasmus never espoused Epicureanism as a comprehensive system of thought, and he could not endorse the central tenet of the mortality of the human soul. He was, however, attracted to the Epicurean ideal of peace of mind through the retreat from worldly cares and the cultivation of a clear moral conscience. As Reinier Leushuis writes, Erasmus’ very last familiar colloquy, The Epicurean, published in 1533, contains the startling claim that no one better deserves the name “Epicurean” than the revered prince of Christian philosophy, Christ himself (CWE 40:1086; ASD I-3:731). Christ teaches his followers how to attain a state of complete tranquility, and freedom from the torments of a guilty conscience, that corresponds to the Epicurean ideal of ataraxia. This ideal, it is worth noting, is not the same as Stoic apathy, which Erasmus carefully disassociates from Christianity in various places including the Ecclesiastes. He points out that apathy would defeat the purpose of the Christian preacher who tries to arouse the emotions of the audience. The Christian ought to combine compassion with a clear conscience in order to achieve tranquility. This understanding of Christianity has little in common with the sterner tenor of Protestant thought, and may explain why Martin Luther labeled Erasmus an Epicurean in the vulgar sense of an atheist or unbeliever. Finally, it may not be out of place here to point out that, through his mature, non-dogmatic embrace of Epicureanism, Erasmus shows some affinity for the late Renaissance prose writer Michel de Montaigne.

3. The Word

Speech, for Erasmus, is not only a defining attribute of humanity but also a key to the relation between humanity and divinity, which was a central preoccupation of his thought. The Gospel of John declares that in the beginning was the logos, which Erasmus famously, or infamously, retranslated as sermo in preference to the reading of the Vulgate, verbum. Erasmus felt justified in changing the reading of the Vulgate, but only in the second edition of his New Testament published in 1519, because the received text of scripture is not divine. The words are human, or rather, a mediation between the human and the divine. The Bible is speech, and as such it must be read, interpreted, and understood according to the arts of speech. Moreover, the arts of speech are the only means we have of approaching divinity. Speech brings man close to God.

a. Humanist Theology

It is not entirely clear under what circumstances Erasmus first took an interest in biblical scholarship. His meeting with John Colet in England is known to have kindled his interest. Another factor, and perhaps an independent factor, was his discovery, in the summer of 1504 at the Praemonstratensian abbey of Parc just outside the walls of Louvain, of the manuscript of Lorenzo Valla’s Annotations on the New Testament, completed fifty years earlier. Erasmus prepared the editio princeps in Paris in 1505 with a prefatory epistle addressed to Christopher Fisher, papal protonotary and doctor of canon law. This preface in defense of Valla can be read as a sort of paradoxical encomium, or praise of invective, since Valla had a controversial reputation as a harsh critic and bitter polemicist. Erasmus compares Valla to Zoilus, a proverbial figure of odious slander for his presumptuous critique of Homeric epic, as we are reminded in the Adages; but here, in the preface he carries a positive connotation as a heroic censor. In his masterpiece on the elegance of the Latin language, Valla rescued literature from barbarity by administering the harsh medicine of criticism to the inveterate disease of scholastic Latin. Erasmus published an epitome of Valla’s work in 1531 based on an abstract he had composed many years earlier in the monastery at Steyn. Valla had collated the Vulgate with the Greek text of the New Testament and emended the translation according to grammatical criteria, including the criterion of elegance. Surely, Erasmus asks, translation, whether of sacred or profane texts, is the purview of grammar. A translator is not a prophet. The prophet requires the gift of the Holy Spirit, but the translator needs grammar and rhetoric, the arts of language. In effect, since the word of God reaches us through human intermediaries using human language, theology cannot dispense with skill in language or linguarum peritia. This is the program of humanist theology.

The fervor with which the letter to Fisher defends Valla’s biblical philology suggests that Erasmus had already begun a similar enterprise himself. Indeed, the text that Erasmus edited in 1505 was the model and impulse for his own Annotations on the New Testament first published as part of the Novum Instrumentum in 1516. Jacques Chomarat has demonstrated convincingly how much Erasmus owed to Valla’s precedent and how little he acknowledged it, often expressing severe criticism of Valla’s choices, which can be taken as a sort of mimetic tribute to Valla, the modern Momus or god of criticism. Even the substitution of sermo for verbum, which embroiled Erasmus in such endless quarrels, and earned him a denunciation from the pulpit of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, was anticipated by Valla in his notes on the Gospel of John. Often the Erasmian Annotations revisits the themes first broached in the prefatory epistle to Fisher, including the notion that the Bible, like all human language, is immersed in historical time.

Chomarat draws our attention to Erasmus’ annotation on Acts 10.38, where the apostle Peter is preaching to the Roman soldier Cornelius. Peter tells Cornelius that God anointed Jesus, which the Vulgate renders with a turn of phrase that elicits a long commentary from Erasmus, lengthened in successive editions. First of all, he observes, though the New Testament is written in Greek, it’s not clear whether Peter was speaking Greek or Hebrew, that is to say the local dialect of Hebrew. If he spoke Greek, he spoke it as a foreign language inflected by his own vernacular, which accounts for stylistic irregularities. After all, the apostles were only human, subject to error and ignorance like the rest of us. This got Erasmus in a lot of trouble. He rounds off his note with a disclaimer: “I’m not the oracle; you can take my opinion or leave it.” This pronouncement coincides with similar disclaimers throughout his biblical scholarship and his apologies. To his implacable foe Edward Lee, Erasmus insists that his opinions are not dogmas to be taken on faith but only ideas to be debated: excutienda propono non sequenda (ASD IX-4:46). In humanist theology, both the text and the exegete are fallible.

b. The Ethics of Speech

Erasmus’ main statement on human speech comes at the beginning of his Paraphrase on the Gospel of John, published in 1523 between the third and fourth editions of his Annotations. Speaking in the voice of the evangelist, he acknowledges that the nature of God surpasses human understanding, and exceeds all of our powers of representation. Consequently, it is better to believe in God than to try to understand him through human reason. Christian philosophy is a kind of fideism, and not a speculative theology. But, in order to convey some understanding of things that are neither intelligible to us nor explainable by us, we have to use names of things that are familiar to our senses, though there is nothing in reality that is truly analogous to God. Therefore, just as the Bible calls that highest mind God, so it calls his only Son its speech. For the Son, though not identical to the Father, nevertheless resembles him through perfect similitude. In the same way, speech is the true mirror of the mind. In this sense, John’s logos is the paradigm of human speech. There is something miraculous about human speech which, arising from the inner recesses of the mind and passing through the ears of the listener, by a kind of occult energy transfers the soul of the speaker to the soul of the listener. This “occult energy” is not divine but nevertheless insinuates the proximity of the human and the divine. Christ is called the logos because God wanted to make himself known to us through him, so that we might be saved. Speech is the gateway to eternity.

The topos of the mirror of speech runs throughout Erasmus’ work as a guiding thread of his ethical and religious thought. It is the figure of speech that animates his philosophy. We find the mirror in the Praise of Folly, in several adages, and in the Lingua. In the latter, it is associated with a saying of Socrates, “Speak that I may see you,” that reappears in the Apophthegmata, whose prefatory epistle to William of Cleves cites Plutarch’s claim that, more than any deeds, sayings are the true mirror of the mind. Erasmus’ last work, the Ecclesiastes devotes a rather important development to the exalted role of speech as the true mirror and image of the soul. In all these instances, we should recognize the expression not of a linguistic theory but rather of a moral imperative. Our society and our salvation depend, according to Erasmus’ favorite figure of speech, on the coincidence of our words and thoughts.

Erasmus brings out this dimension of his theme best in the Lingua of 1525, which identifies the tongue as the source of our greatest benefits and ills. If speech is a mirror, he explains ruefully, it can certainly be a distorting mirror. Christ wanted to be called the logos and the truth, so that we would be ashamed of lying, but now even Christians have become so accustomed to lying that they don’t even realize they are lying. This sad state of affairs is the occasion for a very solemn admonition: “Once lying becomes acceptable, then we can have no more trust, and without trust we lose all human society” (CWE 29:316; ASD IV-1A:83). True speech is the foundation of society, and once this foundation is cracked, the social edifice collapses. At the end of the sixteenth century Michel de Montaigne will make the very same claim in the same prophetic tones, first in his essay “On liars” and again in the essay “On giving the lie.” Both writers experienced their age as a crisis of truth and language. If we want to do justice to the prolific and multifarious achievement of Desiderius Erasmus, we might say that he devoted his life to the ethics of speech.

4. A Controversial Legacy

a. Canon Formation

Since his death in 1536, Erasmus can hardly be said to have rested in peace. His adversaries and detractors were unappeased by his earthly disappearance, and his partisans and disciples shared some of his enthusiasm for polemic. One way to assess Erasmus’ legacy is to trace the publication history of his work, or what we might call the making of his canon. Erasmus himself was thinking about an edition of his complete works as early as 1523, as we know from a letter he sent to Johann von Botzheim in which he drew up a preliminary catalogue of his works to be edited in nine separate tomes with a tenth tome pending. The first tome was to include everything that concerns literature and education including all his translations from Lucian, Euripides, and Libanius. Tome two was reserved for the adages, and tome three for his correspondence. Volume four would be devoted to moral philosophy, including his various translations from Plutarch’s Moralia, and his original works such as the Praise of Folly, the Education of a Christian Prince, and the Complaint of Peace. Volume five was to handle works of religious instruction such as the Enchiridion, his psalm commentaries, and all the prefaces to his New Testament. Eventually, his Ecclesiastes would be included in this group. Volume six would consist of the New Testament and the Annotations, while volume seven was for the Paraphrases. Volume eight was supposed, on a conservative estimate, to hold all the Apologies, or polemical writings. Volume nine was for the Letters of St. Jerome, as if Erasmus wrote them himself, and time permitting, he promised to write a commentary on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans to fill volume 10. Erasmus revised his plan in a letter addressed to the Scottish historian Hector Boece in 1530, partly to accommodate all he had written in the intervening seven years. As a practical measure, the works are now distributed in series, or ordines, rather than individual volumes, and a few other modifications are introduced. The Paraphrases join the New Testament in ordo six to make room for all of Erasmus’ translations of the Greek Fathers in ordo seven. The ninth series now includes several Latin Fathers in addition to Jerome, and the plans for a tenth volume have been shelved. When the posthumous Opera omnia finally issued, from the Froben press of Basel in the course of 1538 to 1540, the publishers followed Erasmus’ plan, but once again separated New Testament and Paraphrases into orders six and seven, while the projected volume of Latin Fathers was canceled. The Apologies occupy the ninth and final order. This is substantially the same organization adopted by the French Protestant refugee Jean Le Clerc in his ten volume edition of the Opera omnia published in Leiden during the first decade of the eighteenth century. This edition is known as LB from the Latin name for the place of publication, Lugduni Batavorum. Le Clerc had to add a tenth volume to accommodate all the Apologies. As a further innovation, he even added an Index Expurgatorius, or repertory of all the passages in Erasmus’ work that were marked out for expurgation by the Spanish and the Roman censors, keyed to the pagination of the Basel edition. From this index it appears that the censors were particularly interested in the correspondence, and that only ordo eight, consisting of Latin translations of the Greek Fathers, escaped their vigilance.

b. Censorship

Le Clerc’s index is an opportune reminder that during the century and a half intervening between the Basel edition and LB, the history of the reception of Erasmus is largely a history of censorship. The Counter-Reformation devoted a fair amount of its institutional effort to the suppression of Erasmus’ legacy in Italy. The first indices of prohibited books were municipal lists whose scope of enforcement was necessarily restricted. In 1555 the Congregation of the Index promulgated the first papal Index of Prohibited Books, which included several titles of Erasmus such as the Annotations on the New Testament, the Colloquies, the Praise of Folly, the Enchiridion, and some writings on prayer and on celibacy. This index was suspended shortly after its promulgation but it did deter Italian printers from publishing new editions of Erasmus’ work. Then in 1559 the papacy promulgated a new index which inscribed Erasmus among the first class of heretics whose works were banned in entirety. This index in turn provoked a major incidence of book burning in the capital of European printing, Venice. Pope Pius IV issued a revised index in the wake of the Council of Trent, the Tridentine Index of 1564, which relaxed the comprehensive ban on Erasmus’ work. However, it also included new provisions for enforcement that resulted in the confiscation and destruction of a considerable number of Erasmus editions in the stock of Italian booksellers. The Tridentine Index also included a new provision for the expurgation of those works by Erasmus that were not banned outright. This provision yielded, after some delay, one of the more important printing and publishing ventures of the Counter Reformation, namely the official expurgated edition of Erasmus’ Adages. This was commissioned by the Council of Trent, prepared by Paolo Manuzio, prefaced by his son Aldo, and published in Florence by the Giunti in 1575 bearing the imprimatur of Pope Gregory XIII. This was the censored edition of the Adages, purged of anything that could give offense to pious ears, and from which all traces of its author, Desiderius Erasmus, were so scrupulously removed that the work is often catalogued as the Adages of Paolo Manuzio. It’s a blessing that readers beyond Italy had access to the unexpurgated edition of the Adages, for if Montaigne had had to rely on Paolo Manuzio’s version, he never would have invented the essay form. Subsequent revisions of the Index of Prohibited Books gradually abandoned the project of further expurgation. The index of Pope Clement VIII in 1596 turned over the task of expurgation to individual readers relying on their own conscience or someone else’s directions. Eventually the papacy resigned itself to the presence of some copies of Erasmus’ literary and educational writings in private libraries in Italy.

c. Scholarship

Just as the era preceding the LB was an era of censorship, so the succeeding era has been, for the study of Erasmus, an era of burgeoning scholarship. The twentieth century in particular initiated several monuments of modern scholarship. From 1906 to 1958, P. S. Allen and his collaborators published in twelve volumes, with the Oxford University Press, the complete correspondence of Erasmus, the Opus epistolarum Desiderii Erasmi Roterodami. It has completely superseded the third ordo of his Opera omnia. In 1933, Wallace Ferguson published, as a supplement to the LB, his Erasmi opuscula, including Erasmus’ biography of St. Jerome. In the same year Hajo Holborn published an important edition of several key texts including what remains today the standard edition of the Enchiridion. In 1969 an international committee based in the Netherlands began publishing the critical edition of the complete works of Erasmus known as ASD. Finally, in 1974, the University of Toronto Press launched its complete works of Erasmus in English translation known as CWE, for Collected Works of Erasmus. Both of those projects are still under way in the spirit of that royal adage Festina lente. Every year, under the auspices of the Erasmus of Rotterdam Society (which also publishes the journal Erasmus Studies, formerly the Erasmus of Rotterdam Society Yearbook), the Margaret Mann Phillips Lecture is delivered in the Spring and the Birthday Lecture in the Fall in order to commemorate and conserve the cultural and ethical legacy of Erasmus. The Society has credited an Erasmus website at erasmussociety.org.

5. References and Further Reading

a. Editions

- Opus epistolarum Desiderii Erasmi Roterodami. Ed. P.S. Allen et al. 12 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1906-1958.

- Opera omnia Desiderii Erasmi Roterodami. Amsterdam, 1969–. ASD

- Desiderii Erasmi Roterodami opera omnia. Ed. Jean Le Clerc. 10 vols. Leiden: P. van der Aa, 1703-1706. (LB)

- Ausgewählte Werke. Ed. Hajo Holborn. Munich: C.H. Beck’sche, 1933.

- Erasmi opuscula. Ed. Wallace Ferguson. The Hague: Martin Nijhoff, 1933.

- Collected Works of Erasmus. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974-. (CWE)

b. Studies

- Boyle, Marjorie O’Rourke. Erasmus on Language and Method in Theology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977.

- Chomarat, Jacques. “Les Annotations de Valla, celles d’Erasme et la grammaire.” In Histoire de l’exégèse au XVIe siècle. Geneva: Droz, 1978.

- Grendler, Paul. “The Survival of Erasmus in Italy.” Erasmus in English 8 (1976). 2-22.

- Leushuis, Reinier. “The Paradox of Christian Epicureanism in Dialogue: Erasmus’ Colloquy The Epicurean.” Erasmus Studies 35 (2015). 113-136.

- Meer, Tineke ter. “A True Mirror of the Mind: Some Observations on the Apophthegmata of Erasmus.” Erasmus of Rotterdam Society Yearbook 23 (2003) 67-93.

- Monfasani, John. “Erasmus and the Philosophers.” Erasmus of Rotterdam Society Yearbook 32 (2012). 47-68.

- Popkin, Richard. The History of Scepticism from Erasmus to Descartes. New York: Harper and Row, 1968.

- Thompson, Craig. “Introduction.” In Erasmus, Literary and Educational Writings. Vol. 1. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1978. CWE 23.

Author Information

Eric MacPhail

Email: macphai@indiana.edu

Indiana University

U. S. A.