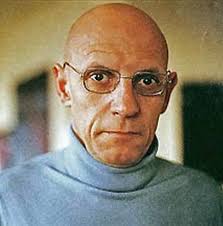

Michel Foucault (1926–1984)

Michel Foucault was a major figure in two successive waves of 20th century French thought–the structuralist wave of the 1960s and then the poststructuralist wave. By the premature end of his life, Foucault had some claim to be the most prominent living intellectual in France.

Michel Foucault was a major figure in two successive waves of 20th century French thought–the structuralist wave of the 1960s and then the poststructuralist wave. By the premature end of his life, Foucault had some claim to be the most prominent living intellectual in France.

Foucault’s work is transdisciplinary in nature, ranging across the concerns of the disciplines of history, sociology, psychology, and philosophy. At the first decade of the 21st century, Foucault is the author most frequently cited in the humanities in general. In the field of philosophy this is not so, despite philosophy being the primary discipline in which he was educated, and with which he ultimately identified. This relative neglect is because Foucault’s conception of philosophy, in which the study of truth is inseparable from the study of history, is thoroughly at odds with the prevailing conception of what philosophy is.

Foucault’s work can generally be characterized as philosophically oriented historical research; towards the end of his life, Foucault insisted that all his work was part of a single project of historically investigating the production of truth. What Foucault did across his major works was to attempt to produce an historical account of the formation of ideas, including philosophical ideas. Such an attempt was neither a simple progressive view of the history, seeing it as inexorably leading to our present understanding, nor a thoroughgoing historicism that insists on understanding ideas only by the immanent standards of the time. Rather, Foucault continually sought for a way of understanding the ideas that shape our present not only in terms of the historical function these ideas played, but also by tracing the changes in their function through history.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Early works on psychology

- Archaeology

- Genealogy

- Governmentality

- Ethics

- References and Further Reading

1. Life

Michel Foucault was born Paul-Michel Foucault in 1926 in Poitiers in western France. His father, Paul-André Foucault, was an eminent surgeon, who was the son of a local doctor also called Paul Foucault. Foucault’s mother, Anne, was likewise the daughter of a surgeon, and had longed to follow a medical career, but her wish had to wait until Foucault’s younger brother as such a career was not available for women at the time. It is surely no coincidence then that much of Foucault’s work would revolve around the critical interrogation of medical discourses.

Foucault was schooled in Poitiers during the years of German occupation. Foucault excelled at philosophy and, having from a young age declared his intention to pursue an academic career, persisted in defying his father, who wanted the young Paul-Michel to follow his forebears into the medical profession. The conflict with his father may have been a factor in Foucault’s dropping the ‘Paul’ from his name. The relationship between father and son remained cool through to the latter’s death in 1959, though Foucault remained close to his mother.

He moved to Paris in 1945, just after the end of the war, to prepare entrance examinations for the École Normale Supérieure d’Ulm, which was then (and still is) the most prestigious institution for education in the humanities in France. In this preparatory khâgne year, he was taught philosophy by the eminent French Hegelian, Jean Hyppolite. Foucault entered the École Normale in 1946, where he was taught by Maurice Merleau-Ponty and mentored by Louis Althusser. Foucault primarily studied philosophy, but also obtained qualifications in psychology. These years at the École Normale were marked by depression – and attempted suicide – which is generally agreed to have resulted from Foucault’s difficulties coming to terms with his homosexuality. While at the École Normale, Foucault also joined the French Communist Party in 1950 under the influence of Althusser, but was never active and left with Althusser’s assent thoroughly disillusioned in 1952.

Foucault aggregated in philosophy from the École Normale in 1951. The same year, he began teaching psychology there, where his students included Jacques Derrida, who would later become a philosophical antagonist of Foucault’s. Foucault also began to work as a laboratory researcher in psychology. He would continue to work in psychology in various capacities until 1955, when he took up a position as a director of the Maison de France at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. From Sweden, he moved to Poland as French cultural attaché in 1958, and then from there moved to the Institut Français in Hamburg in 1959. During these overseas postings, he wrote his first major work and primary doctoral thesis, a history of madness, which was later published in 1961. In 1960, Foucault returned to France to teach psychology in the philosophy department of the University of Clermont-Ferrand. He remained in that post until 1966, during which he lived in Paris and commuted to teach. It was in Paris in 1960 that Foucault met the militant leftist Daniel Defert, then a student and later a sociologist, with whom he would form a partnership that lasted the rest of Foucault’s life.

From 1964, Defert was posted to Tunisia for 18 months of compulsory military service, during which time Foucault visited him more than once. This led to Foucault in 1966 taking up a chair of philosophy at the University of Tunis, where he was to remain until 1968, missing the events of May 1968 in Paris for the most part. 1966 also saw the publication of Foucault’s The Order of Things, which received both praise and critical remarks. It became a bestseller despite its length and the obscurity of its argumentation, and cemented Foucault as a major figure in the French intellectual firmament.

Returning to France in 1968, Foucault presided over the creation and then running of the philosophy department at the new experimental university at Vincennes in Paris. The new university was created as an answer to the student uprising of 1968, and inherited its ferment. Foucault assembled a department composed mostly of militant Marxists, including some who have gone on to be among the most prominent French philosophers of their generation: Alain Badiou, Jacques Rancière, and Étienne Balibar. After scandals related to this militancy, the department was briefly stripped of its official accreditation. Foucault was already moving on, however; he was in 1970 elected to a chair at France’s most prestigious intellectual institution, the Collège de France, which he held for the rest of his life. The only duty of this post is to give an annual series of lectures based on one’s current research. At the time of writing, Foucault’s thirteen Collège lecture series are in the process of being published in their entirety: eight have appeared in French, seven have been published in English.

The early 1970s were a politically tumultuous period in Paris, where Foucault was again living. Foucault threw himself into political activism, primarily in relation to the prison system, as a founder of what was called the “Prisons Information Group.” It originated in an effort to aid political prisoners, but in fact sought to give a voice to all prisoners. In this connection, Foucault became close to Gilles Deleuze, during which friendship Foucault wrote an enthusiastic foreword to the English-language edition of Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus, before Foucault and Deleuze fell out.

In the late ‘70s, the political climate in France cooled considerably; Foucault largely withdrew from activism and turned his hand to journalism. He covered the Iranian Revolution first-hand in newspaper dispatches as the events unfolded in 1978 and 1979. He began to spend more and more time teaching in the United States, where he had lately found an enthusiastic audience.

It was perhaps in the United States that Foucault acquired HIV. He developed AIDS in 1984 and his health quickly declined. He finished editing two volumes on ancient sexuality which were published that year from his sick-bed, before dying on the 26th June, leaving the editing of a fourth and final volume uncompleted. He bequeathed his estate to Defert, with the proviso that there were to be no posthumous publications, a testament which has been subject to ever more elastic interpretation since.

A note on dates: Where there is any disagreement among sources as to the facts of Foucault’s biography, the chronology compiled by Daniel Defert at the start of Foucault’s Dits et écrits is considered in this article to be definitive.

2. Early works on psychology

Foucault’s earliest work lacks a distinctively “Foucauldian” perspective. In these works, Foucault displays influences typical of young French academics of the time: phenomenology, psychoanalysis, and Marxism. Foucault’s primary work of this period was his first monograph, Mental Illness and Personality, published in 1954. This slim volume, commissioned for a series intended for students, begins with an historical survey of the types of explanation put forward in psychology, before producing a synthesis of perspectives from evolutionary psychology, psychoanalysis, phenomenology and Marxism. From these perspectives, mental illness can ultimately be understood as an adaptive, defensive response by an organism to conditions of alienation, which an individual experiences under capitalism. Foucault first modified the book in 1962 in a new edition, entitled Mental Illness and Psychology. This resulted in the change of the later parts – the most Marxist material and the conclusion –to bring them into line with the theoretical perspective that he had by then expounded in his later The History of Madness. According to this view, madness is something natural, and alienation is responsible not so much for creating mental illness as such, but for making madness into mental illness. This was a perspective with which Foucault in turn later grew unhappy, and he had the book go out of print for a time in France.

Foucault’s other major publication of this early period, a long introduction (much longer than the text it introduced) to the French translation of Ludwig Binswanger’s Dream and Existence, a work of Heideggerian existential psychoanalysis, appeared in the same month in 1954 as Mental Illness and Personality. Far from merely introducing Binswanger’s text, Foucault here expounds a novel account of the relation between imagination, dream and reality. He combines Binswanger’s insights with Freud’s, but arguing that neither Binswanger nor Freud understands the fundamental role of dreaming for the imagination. Since imagination is necessary to grasp reality, dreaming is also essential to existence itself.

3. Archaeology

a. The History of Madness

Foucault’s first canonical monograph, in the sense of a work that he never repudiated, was his 1961 primary doctoral thesis, Madness and Unreason: A History of Madness in the Classical Age, which has ultimately come to be known simply as the History of Madness. It is best known in the English-speaking world by an abridged version, Madness and Civilization, since for decades the latter was the only version available in English. History of Madness is a work of some originality, showing several influences, but not slavishly following any convention. It resembles Friedrich Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy in style and form (thought greatly exceeding it in length), proposing a disjunction between reason and unreason similar to Nietzsche’s Apollonian/Dionysian distinction. It also bears the influence of French history and philosophy of science, the most prominent twentieth century representative of which was Gaston Bachelard, the developer of a notion of “epistemological rupture” to which most of Foucault’s works are indebted. Yet Georges Canguilhem’s focus on the division of the normal from the pathological is perhaps the most telling influence on Foucault in this book. Foucault’s thought continues moreover to owe something to Marxism and to social history more generally, constituting an historical analysis of social divisions.

The History of Madness follows logically enough from Foucault’s interest in psychology. The link is stronger even than the title indicates: much of the work is concerned with the birth of medical psychiatry, which Foucault associates with extraordinary changes in the treatment of the mad in modernity, meaning first their systematic exclusion from society in early modernity, followed by their pathologization in late modernity. The History of Madness thus sets the pattern for most of Foucault’s works by being concerned with discrete changes in a given area of social life at particular points in history. Like Foucault’s other major works of the 1960s, it fits broadly into the category of the history and philosophy of science. It has wider philosophical import than that, however, with Foucault ultimately finding that madness is negatively constitutive of Enlightenment reason via its exclusion. The exclusion of unreason itself, concomitant with the physical exclusion of the mad, is effectively the dark side of the valorization of reason in modernity. For this reason, the original main title of the work was Madness and Unreason. Foucault argues in effect for the recuperation of madness, via a valorization of philosophers and artists deemed mad, such as Nietzsche, a recuperation which Foucault thinks the works of such men already portend.

b. Writings on Art and Literature

Foucault’s writings on art and literature have received relatively little attention, even though Foucault’s work is widely influential among scholars of art and literature. This is surely because Foucault’s work directly in these areas is relatively minor and marginal in his corpus. Still, Foucault wrote several short treatments on artists, including Manet and Magritte, and more substantially on literature. In 1963, Foucault wrote a short book on the novelist Raymond Roussel, published in English as Death and the Labyrinth, which is exceptional as Foucault’s only book-length piece of literary or artistic criticism, and which Foucault himself never considered as of a similar importance to his other books of the 1960s. Still, the figure of Roussel offers something of a bridge from The History of Madness and the work that Foucault will now go on to do, not least because Roussel is a writer who could be categorized as rehabilitating madness in the literary sphere. Roussel was a madman – eccentrically suicidal – whose work consisted in playing games with language according to arbitrary rules, but with the utmost dedication and seriousness, the purpose of which was to investigate language itself, and its relation to extra-linguistic things. This latter theme is precisely that which comes to preoccupy Foucault in the 1960s, and in the form too of uncovering the rules of the production of discourse.

Despite that the Roussel book was the only one Foucault wrote on literature, he wrote literary essays throughout the 1960s. He wrote several studies of French literary intellectuals, such as the “Preface to Transgression” about the work of Georges Bataille in relation to that of the Marquis de Sade, the “Prose of Actaeon” about Pierre Klossowski, the “Thought of the Outside” about Maurice Blanchot. These were all figures who wrote literature or wrote about it, but they were also all philosophical thinkers too, influenced by Nietzsche and/or Martin Heidegger: it was through his contemporary Blanchot, a Heideggerian, that Foucault came to Bataille, and thus to Nietzsche, who proved to be a decisive influence on Foucault’s work at multiple points. Foucault also wrote “Language to Infinity,” about de Sade and his literary influence, and a piece on Flaubert at this time. All of these works contribute to a general engagement by Foucault with the theme of language and its relation to its exterior, a theme which is explored at greater length in his contemporaneous monographs.

c. The Birth of the Clinic

The major work of 1963 for Foucault was his follow-up to his The History of Madness, entitled The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. The Birth of the Clinic examines the emergence of modern medicine. It follows on from the History of Madness logically enough: the analysis of the psychiatric classification of madness as disease is followed by an analysis on the emergence of modern medicine itself. However, this new study is a considerably more modest work than the other, due largely to a significant methodological tightening. The preface to The Birth of the Clinic proposes to look at discourses on their own terms as they historically occur, without the hermeneutics that attempts to interpret them in their relation to fundamental reality and historical context. That is, as Foucault puts it, to treat signifiers without reference to the signified, to look at the evolution of medical language without passing judgment on the things it supposedly referred to, namely disease.

The main body of the work is an historical study of the emergence of clinical medicine around the time of the French revolution, at which time the transformation of social institutions and political imperatives combined to produce modern institutional medicine for the first time. The leitmotif of the work is the notion of a medical “gaze”: modern medicine is a matter of attentive observation of patients, without prejudging the maladies one may find, in the service of the demographic needs of society. There is some significant tension between the methodology and the rest of the book, however, with much of what is talked about in the book clearly not being signifiers themselves. The fulfillment of the intention announced at the beginning of The Birth of the Clinic is found rather in Foucault’s next book, The Order of Things, first published in 1966.

d. The Order of Things

Subtitled “An Archaeology of the Human Sciences,” this book aims to uncover the history of what today are called the “human sciences.” This is an obscure area, in fact, certainly to English-speaking readers, who are not often used to seeing the relevant disciplines grouped in this way. The human sciences do not comprise mainstream academic disciplines; they are rather an interdisciplinary space for the reflection on the “man” who is the subject of more mainstream scientific knowledge, taken now as an object, sitting between these more conventional areas, and of course associating with disciplines such as anthropology, history, and, indeed, philosophy. Disciplines identified as “human sciences” include psychology, sociology, and the history of culture.

The mainstay of the book is not concerned with this narrow area, however, but its pre-history, in the sense of the academic discourses which preceded its very existence. In dealing with these, Foucault employs a method which is certainly similar to that of his earlier works, but is now more deliberate, namely the broad procedure of looking for what in the French philosophy of science are called “epistemic breaks.” Foucault does not use this phrase, which originated with Gaston Bachelard, but uses a resonant neologism, “episteme.” In using this term, Foucault refers to the stable ensemble of unspoken rules that governs knowledge, which is itself susceptible to historical breaks. The book tracks two major changes in the Western episteme, the first being at the beginning of the “Classical” age during the seventeenth century, and the second being at the beginning of a modern era at the turn of the nineteenth. Foucault does not concern himself here with why these shifts happen, only with what has happened. This then, is now the work that he calls “archaeology.” In the original preface to The History of Madness, Foucault describes what he is doing as the “archaeology” of madness. This notion, used here apparently off-handedly, becomes the name of Foucault’s research project through the 1960s. In The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault once again uses the word “archaeology” only once, but this time in the subtitle itself. Only with The Order of Things is archaeology formulated as a methodology.

In The Order of Things, Foucault is concerned only to analyze the transformations in discourse as such, with no consideration of the concrete institutional context. The consideration of that context is now put aside until the 1970s. He shows that in each of the disciplines he looks at, the precursors of the contemporary discipline of biology, economics, and linguistics, the same general transformations occur at roughly the same time, encompassing myriad changes at a local level that might not seem connected to one another.

Before the Classical age, Foucault argues, Western knowledge was a rather disorganized mass of different kinds of knowledge (superstitious, religious, philosophical), with the work of science being to note all kinds of resemblances between things. With the advent of the Classical Age, clear distinctions between academic disciplines emerge, part of a general enthusiasm for categorizing information. The aim at this stage is for a total, definitive cataloguing and categorization of what can be observed. Science is concerned with superficial visibles, not looking for anything deeper. Language is understood as simply transparently representing things, such that the only concern with language is work of clarification. For the first time, however, there is an appreciation of the reflexive role of subjects in the enquiry they are conducting – the scientist is himself an object for enquiry, an individual conceived simultaneously as both subject and object. Then, from the beginning of the nineteenth century, a new attention to language emerges, and the search begins for precisely what is hidden from our view, hidden logics behind what we can see. To this tendency belong theories as diverse as the dialectical view of history, psychoanalysis, and Darwinian evolution. Foucault criticises all such thought as involving a division between what is “the Same” and what is other, with the latter usually excluded from scientific inquiry, focusing all the time on “man” as a privileged object of inquiry. Foucault ultimately argues, however, that there are signs of the end of “man” as an object of knowledge, as our thought, in the shape of the “counter-sciences” of psychoanalysis and ethnology, plumbs areas beyond what can be understood in terms of the concept of “man.” One sees, again, the valorization here of mad writers, such as Roussel and Nietzsche: the historico-philosophical thesis of The History of Madness, and its project of the recuperation of madness, is here inscribed in terms of the production of knowledge.

e. The Archaeology of Knowledge

Foucault followed the Order of Things with his Archaeology of Knowledge, which was published in 1969. In this work, Foucault tries to consolidate the method of archaeology: it is the only one of Foucault’s major works that does not comprise an historical study, and thus his most theoretical work. It is the most influential work of Foucault’s in literary criticism and some other applied areas.

Archaeology, Foucault now declares, means approaching language in a way that does not refer to a subject who transcends it – though he acknowledges he has not been rigorous enough in this respect in the past. That is not to say that Foucault is making a strong metaphysical claim about subjectivity, but rather only that he is proposing a mode of analysis that subordinates the role of the subject. Foucault in fact proposes to suspend acceptance not only of the notion of a subject who produces discourse but of all generally accepted discursive unities, such as the book. Instead, he wants to look only at the surface level of what is said, rather than to try to interpret language in terms of what stands behind it, be that hidden meaning, structures, or subjects. Foucault’s suggestion is to look at language in terms of discrete linguistic events, which he calls “statements,” such as to understand the multitudinous ways in which statements relate to one another. Foucault’s statement is not defined by content (a statement is not a proposition), nor by its simple materiality (the sounds made, the marks on paper). The specificity of a statement is rather determined both by such intrinsic properties and by its extrinsic relations, by context as well as content.

Foucault asserts the autonomy of discourse, that language has a power that cannot be reduced to other things, either to the will of a speaking subject, or to economic and social forces, for example. This is not to say that statements exist independently of extra-linguistic reality, however, or of larger “discursive formations” in which they occur. It is rather the opposite. Both these things in effect need to be factored into analyses of statements – the identity of the statement is conditioned both by its relation to other statements, to discourse as such, and to reality, as well as by its intrinsic form. The statement is governed by a “system of its functioning,” which Foucault calls the “archive.” Archaeology is now interpreted as the excavation of the archive. This of course retroactively includes much of what Foucault has been doing all along.

Foucault followed this work with his celebrated 1969 essay, “What is an Author?” (somewhat confusingly because many versions of this circulate, including multiple translations of the original, and Foucault’s own translation, was delivered in English many years later), which effectively concludes the series of Foucault’s writings on literature in the 1960s. This work represents an extension in literary theory of the impulse behind the Archaeology, with Foucault systematically criticizing the notion of an author, and suggesting that we can move beyond ascribing transcendent sovereignty to the subject in our understanding of discourse, understanding the subject rather as a function of discourse.

4. Genealogy

The period after May 1968 saw considerable social upheaval in France, particularly in the universities, where the revolt of that month had begun. Foucault, returning to this atmosphere from a Tunis that was also in political ferment, was politicized.

His work quickly reflected his new engagement (the Archaeology was completed early in 1968, though published the next year). His inaugural lecture at the Collège de France in 1970, published in French as The Order of Discourse (L’ordre du discours – it is available in diverse anthologized English translations under various titles, including as an appendix to the American edition of The Archaeology of Knowledge), represented an attempt to move the analysis of discourse that had preoccupied him through the 1960s onto a more political terrain, asking questions now about the institutional production of discourse. Here, Foucault announces a new project, which he designates “genealogy,” though Foucault never repudiates the archaeological method as such.

“Genealogy” implies doing what Foucault calls the “history of the present.” A genealogy is an explanation of where we have come from: while Foucault’s genealogies stop well before the present, their purpose is to tell us how our current situation originated, and is motivated by contemporary concerns. Of course, one may argue that all history has these features, but with genealogy this is intended rather than a matter of unavoidable bias. Some of Foucault’s archaeologies can be said to have had similar features, but their purpose was to look at epistemic shifts discretely, in themselves, without insisting on this practical relevance. The word “genealogy” is drawn directly from Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals: genealogy is a Nietzschean form of history, though rather more meticulously historical than anything Nietzsche ever attempted.

a. Discipline and Punish

In the early 1970s, Foucault’s involvement with the prisoners’ movement led him to lecture two years running on prisons at the Collège de France, which led to his work in 1975: Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. The subtitle here references The Birth of the Clinic, indicating some continuity of project; both titles in turn of course reference Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy.

Discipline and Punish is a book about the emergence of the prison system. The conclusion of the book in relation to this subject matter is that the prison is an institution, the objective purpose of which is to produce criminality and recidivism. The system encompasses the movement that calls for reform of the prisons as an integral and permanent part. This thesis is somewhat obscured by a particular figure from the book that has garnered much more attention, namely Jeremy Bentham’s “panopticon,” a design for a prison in which every prisoner’s every action was visible, which greatly influenced nineteenth century penal architecture, and indeed institutional architecture more generally, up to the level of city planning. Though Foucault is often presented as a theorist of “panopticism,” this is not the central claim of the book.

The more important general theme of the book is that of “discipline” in the penal sense, a specific historical form of power that was taken up by the state with professional soldiering in the 17th century, and spread widely across society, first via the panoptic prison, then via the division of labor in the factory and universal education. The purpose of discipline is to produce “docile bodies,” the individual movements of which can be controlled, and which in its turn involves the psychological monitoring and control of individuals, indeed which for Foucault produces individuals as such.

b. The Will to Knowledge

Foucault indeed focused on the concept of power so much that he remarked that he produced the analysis of power relations rather than the genealogies he had intended. Foucault began talking about power as soon as he began to do genealogy, in The Order of Discourse. In Discipline and Punish he develops a notion of “power-knowledge,” recombining the analysis of the epistemic with analysis of the political. Knowledge now for Foucault is incomprehensible apart from power, although Foucault continues to insist on the relative autonomy of discourse, introducing the notion of power-knowledge precisely as a replacement for the Marxist notion of ideology in which knowledge is seen as distorted by class power; for Foucault, there is no pure knowledge apart from power, but knowledge also has real and irreducible importance for power.

Foucault sketches a notion of power in Discipline and Punish, but his conception of power is primarily expounded only in a work published the following year in 1976, the first volume of his History of Sexuality, with the title The Will to Knowledge. The latter is a reference to Nietzsche’s Will to Power (this original French title is that of the current Penguin English edition – the English translation published in America, however, is titled simply The History of Sexuality: An Introduction).

The Will to Knowledge is an extraordinarily influential work, perhaps Foucault’s most influential. The central thesis of the book is that, contrary to popular perceptions that we are sexually repressed, the entire notion of sexual repression is part and parcel of a general imperative for us to talk about sex like never before: the production of behavior is represented simply as the liberation of innate tendencies.

The problem, says Foucault, is that we have a negative conception of power, which leads us only to call power that which prohibits, while the production of behavior is not problematized at all. Foucault claims that all previous political theory has found itself stuck in a view of power propagated in connection to absolute monarchy, and that our political thought has not caught up with the French Revolution, hence there is today a need “to cut off the head of the king” in political theory. Foucault’s point is that we imagine power as being a thing that can be possessed by individuals, as organized pyramidally, with one person at the apex, operating via negative sanctions. Foucault argues that power is in fact more amorphous and autonomous than this, and essentially relational. That is, power consists primarily not of something a person has, but rather is a matter of what people do, subsistsing in our interactions with one another in the first instance. As such, power is completely ubiquitous to social networks. People, one may say crudely, moreover, are as much products of power as they are wielders of it. Power thus has a relative autonomy apropos of people, just as they do apropos of it: power has its own strategic logics, emerging from the actions of people within a network of power relations. The carceral system and the device of sexuality are two prime examples of such strategies of power: they are not constructed deliberately by anyone or even by any class, but rather emerge out of themselves.

This leads Foucault to an analysis of the specific historical dynamics of power. He introduces the concept of “biopower,” which combines disciplinary power as discussed in Discipline and Punish, with a “biopolitics” that invests people’s live at a biological level, “making” us live according to norms, in order to regulate humanity at the level of the population, while keeping in reserve the bloody sword of “thanatopolitics,” now exaggerated into an industrial warfare that kills millions. This specific historical thesis is dealt with in more detail in the article Foucault and Feminism, in the first section. Foucault’s concerns with sexuality, bodies, and norms form a potent mix that has, via the work of Judith Butler in particular, been one of the main influences on contemporary feminist thought, as well as influential in diverse areas of the humanities and social sciences.

c. Lecture Series

After his lectures on prisons, Foucault for two years returned to the old theme of institutional psychiatry in work that effectively provides a bridge between the theme (and theory) of the genealogy of prisons, and that of sexuality. The first of these, Psychiatric Power, is a genealogical sequel to the The History of Madness. The second, Abnormal, is closer to The Will to Knowledge: as its title suggests, it is concerned with the production of norms, though again not straying far from the psyciatric context. The following year, 1976, Foucault lectured on the genealogy of racism in Society Must Be Defended, which provides a useful companion to The Will to Knowledge, and contains perhaps the clearest exposition of Foucault’s thoughts on biopower. The publication of these lecture series, and, a fortiori, of the lecture series that were given in the eight years in between the publication of The Will to Knowledge and the deathbed publication of the next volumes of The History of Sexuality are transforming our picture of Foucault’s later thought.

5. Governmentality

The notion of biopolitics, as the regulation of populations, brought Foucault’s thinking to the question of the state. Foucault’s work on power had generally been a matter of minimizing the importance of the state in the network of power relations, but now he started to ask about it specifically, via a genealogy of “government,” first in Security, Territory, Population, and then in his genealogy of neoliberalism, The Birth of Biopolitics. Foucault here coins the term “governmentality,” which has a rather shifting meaning.

The function of the notion of governmentality is to throw the focus of thinking about contemporary societies onto government as such, as a technique, rather than to focus on the state or the economy. Well before the publication of these lecture series in recent years, one of these lectures from Security, Territory, Population, dealing with this concept and published in English as “Governmentality,” had already become the basis for what is effectively an entire school of sociology and political theory.

This notion of government takes Foucault’s researches on biopower and puts them on a more human plane, in a tendential move away from the bracketing of subjectivity that had marked Foucault’s approach up to that point. The notion of government for Foucault, like that of power, straddles a gap between the statecraft that is ordinarily called “government” today, and personal conduct, so-called “government of the self.” The two are closely related inasmuch as, in a rather Aristotelian way, governing others depends on one’s relation to oneself. This thematic indeed takes Foucault in precisely the direction of Ancient Greek ethics.

6. Ethics

Foucault’s final years lecturing at the Collège de France, the early 1980s, saw Foucault’s attention move from modern reflections on government, first to Christian thought, then to Ancient. Foucault is here following the genealogy of government, but there are other factors at work. Another reason for this trajectory is the History of Sexuality project, for which Foucault found it necessary to move further and further back in time to trace the roots of contemporary thinking about sex. However, one might ask why Foucault never found it necessary to do this with any other area, for example madness, where doubtless the roots could have been traced further back. Another reason for this turn, then, at this time was a changed climate in French academe, where, the political militancy of the seventies in abeyance, there was a general “turn to ethics.”

The ultimate output of this period was the second and third volumes of the History of Sexuality, written and published at the same time, and constituting in effect a single intellectual effort. These volumes deal with Ancient sex literature, Greek and then Roman. They lack great theoretical conclusions like those of the first volume. They are patient studies of primary texts, and ones that are further from the present, both in the sense of dealing with more chronologically remote material, and in the sense of their relevance to our present-day concerns, than any others Foucault ever made. The relevance of the historical analysis is particularly unclear due to the absence of the fourth volume of the History of Sexuality. It was partially drafted but far from complete, and hence is unpublished and likely to remain so. In dealing with the Christian part of the history of the sexuality, it serves to link the second and third volumes to the first.

The extant volumes chart the changes that occurred within Ancient thinking about sex, between Greek and Roman thinking. There are certainly significant changes over the thousand years of Ancient writing about sex – an increasing attention on individuals for example – but for the purposes of the present it is the general differences between Ancient and modern attitudes that is more instructive. For the Ancients, sex was consistently a relatively minor ethical concern, simply one of many concerns relevant to diet and health more generally.

What Foucault got from studying this material, which he discussed in relation to the present primarily elsewhere than in these two books, is the notion of an ethics concerned with one’s relation to one’s self. Self-constitution is the overarching problematic of Foucault’s research in his final years. This “care for the self” Foucault manifestly finds attractive, though he is scathing of the precise modality it takes in patriarchal Ancient society, and he expresses some wish to resurrect such an ethics today, though he demurs on the question of whether such a resurrection is really possible. Thus, the point for Foucault is not to expound an ethics; it is rather the new analytical possibilities of focusing on subjectivity itself, rather than bracketing it as Foucault had tended to do previously. Foucault becomes interested increasingly in the way subjectivity is constituted precisely by the way in which subjects produce themselves via a relation to truth. Foucault now proclaims that his work was always about subjectivity. The dry investigations of the 1960s, while concerned explicitly about truth, were always about the way in which “the human subject fits into certain games of truth.”

7. References and Further Reading

Below is a list of English translations of works by Foucault that are named above, in the order they were originally written. The shorter writings and interviews of Foucault are also of extraordinary interest, particularly to philosophers. In French, these have been published in an almost complete collection, Dits et écrits, by Gallimard, both in a four volume edition and a two-volume edition. In English, however, Foucault’s shorter works are spread across many overlapping anthologies, which even between them omit much that is important. The three-volume Essential Works series of anthologies, published by Penguin and the New Press, and edited by Paul Rabinow (vol. 1 Ethics, vol. 2 Aesthetics, vol. 3 Power), are the closest to a comprehensive collection in English, although the most compendious single-volume anthology is Foucault Live. Edited by Sylvère Lotringer. New York: Semiotext(e), 1996.

a. Primary

- Mental illness and psychology. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- The History of Madness. London: Routledge, 2006.

- Death and the Labyrinth. London: Continuum, 2004.

- Birth of the Clinic. London: Routledge, 1989.

- The Order of Things. London: Tavistock, 1970.

- The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon, 1972.

- Psychiatric Power. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Discipline and Punish. London: Allen Lane, 1977.

- Abnormal. London: Verso, 2003.

- Society Must Be Defended. New York: Picador, 2003.

- An Introduction. Vol. 1 of The History of Sexuality. New York: Pantheon, 1978. Reprinted as The Will to Knowledge, London: Penguin, 1998.

- Security, Territory, Population. New York: Picador, 2009.

- The Birth of Biopolitics. New York: Picador, 2010.

b. Secondary

- Timothy J. Armstrong (ed.). Michel Foucault: Philosopher. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992.

- A particularly good collection of papers on Foucault from his contemporaries.

- Gilles Deleuze. Foucault. Trans. Seán Hand. London: Athlone, 1988.

- The best book about Foucault’s work, from one who knew him, though predictably idiosyncratic.

- Gary Gutting. Michel Foucault’s archaeology of scientific reason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- The definitive volume on Foucault’s archaeological period, and on Foucault and the philosophy of science.

- Gary Gutting (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Foucault. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Brilliant and comprehensive introductory essays on aspects of Foucault’s thought.

- David Couzens Hoy (ed.). Foucault: A Critical Reader. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986.

- Mark G. E. Kelly. The Political Philosophy of Michel Foucault. New York: Routledge, 2009.

- For the political aspect of Foucault’s thought, from a philosophical perspective.

- David Macey. The Lives of Michel Foucault. London: Hutchison, 1993.

- This is the most comprehensive and most sober of the available biographies of Foucault.

- David Macey. Michel Foucault. London : Reaktion Books, 2004.

- A readable, abbreviated biography of Foucault.

- Michael Mahon. Foucault’s Nietschean Genealogy: Truth, Power, and the Subject. Albany: SUNY Press, 1992.

- A pointedly philosophical work on the influence of Nietzsche on Foucault.

- Jeremy Moss (ed.).The Later Foucault. London: Sage, 1998.

- On Foucault’s late work.

- Barry Smart (ed.). Michel Foucault: Critical Assessments (mutli-volume). London: Routledge, 1995.

Author Information

Mark Kelly

Email: m.kelly@mdx.ac.uk

Middlesex University

United Kingdom