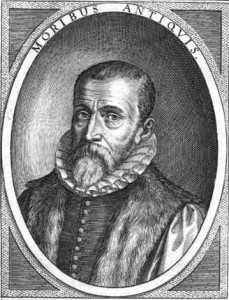

Justus Lipsius (1547—1606)

Justus Lipsius, a Belgian classical philologist and Humanist, wrote a series of works designed to revive ancient Stoicism in a form that would be compatible with Christianity. The most famous of these is De Constantia (‘On Constancy’) in which he advocated a Stoic-inspired ideal of constancy in the face of unpleasant external events, but also carefully distinguished those parts of Stoic philosophy that the orthodox Christian should reject or modify. This modified form of Stoicism influenced a number of contemporary thinkers, creating an intellectual movement that has come to be known as Neostoicism.

Justus Lipsius, a Belgian classical philologist and Humanist, wrote a series of works designed to revive ancient Stoicism in a form that would be compatible with Christianity. The most famous of these is De Constantia (‘On Constancy’) in which he advocated a Stoic-inspired ideal of constancy in the face of unpleasant external events, but also carefully distinguished those parts of Stoic philosophy that the orthodox Christian should reject or modify. This modified form of Stoicism influenced a number of contemporary thinkers, creating an intellectual movement that has come to be known as Neostoicism.

Lipsius has been described as the greatest Renaissance scholar of the Low Countries after Erasmus. The role that he played in the revival of interest in Stoicism during the late Renaissance was similar to that performed by Marsilio Ficino with regard to Platonism and Pierre Gassendi with regard to Epicureanism. As such, he stands as a key figure in the history of Renaissance philosophy and the Renaissance revival of ancient thought.

Table of Contents

1. Background

Justus Lipsius’s philosophical reputation rests upon his status as the principal figure in the Renaissance revival of Stoicism. Stoicism was one of the great Hellenistic schools of philosophy and dominated ancient intellectual life for at least 400 years. Founded by Zeno of Citium around 300 B.C.C., the school developed under Cleanthes, Chrysippus, Panaetius, and Posidonius. In the first century B.C. it appealed to high-ranking Romans including Cicero and Cato. In the first two centuries C.E. it reached its height of popularity under the influence of Musonius Rufus and Epictetus. In the second century C.E. it found its most famous exponent in the form of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. However, after the second century Stoicism was soon eclipsed in popularity by Neoplatonism.

Despite this decline in late antiquity, Stoicism continued to exert an influence. Its ideas were discussed by Church Fathers such as St. Augustine, Lactantius, and Tertullian. In the Middle Ages its impact can be seen in the ethical works of Peter Abelard and his pupil John of Salisbury, transmitted via the readily available Latin works of Seneca and Cicero. In the fourteenth century Stoicism attracted the attention of Petrarch who produced a substantial ethical work entitled De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae (‘On the Remedies of Both Kinds of Fortune’) inspired by Seneca and drawing upon an account of the Stoic theory of the passions made by Cicero. With the rediscovery of the works of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus by famous Humanists such as Perotti and Politian in the fifteenth century, interest in Stoicism continued to develop. However, the Renaissance revival of Stoicism remained somewhat limited until Justus Lipsius.

2.Life

Justus Lipsius (the Latinized version of Joest Lips) was born in Overyssche, a village near Brussels and Louvain, in 1547. He studied first with the Jesuits in Cologne and later at the Catholic University of Louvain. After completing his education he visited Rome, in his new position as secretary to Cardinal Granvelle, staying for two years in order to study the ancient monuments and explore the unsurpassed libraries of classical literature. In 1572 Lipsius’s property in Belgium was taken by Spanish troops during the civil war while he was away on a trip to Vienna (a trip that would later be used as the backdrop for the dialogue in De Constantia over a decade later). Without property, Lipsius applied for a position at the Lutheran University of Jena. This was the first of a number of institutional moves that required Lipsius to change his publicly professed faith. His new colleagues at Jena remained sceptical of this radical transformation and Lipsius was eventually forced to leave Jena after only two years in favour of Cologne. While at Cologne he prepared notes on Tacitus that he used in his critical edition of 1574.

In 1576 Lispius returned to Catholic Louvain. However after his property was looted by soldiers a second time he fled again in 1579, this time to the Calvinist University of Leiden. He remained at Leiden for thirteen years and it is to this period that his two most famous books – De Constantia Libri Duo (1584) and Politicorum sive Civilis Doctrinae Libri Sex (1589) – belong. However, Lipsius was by upbringing a Catholic and eventually he sought to return to Louvain, via a brief period in Liège. In 1592 Lipsius accepted the Chair of Latin History and Literature at Louvain. To this final period belong his editorial work on Seneca and his two detailed studies of Stoicism, the Manuductio ad Stoicam Philosophiam and Physiologia Stoicorum. The two studies were published first in 1604 and the edition of Seneca in 1605. Lipsius died in Louvain in 1606.

Among Lipsius’s friends was his publisher, the famous printer Christopher Plantin, with whom he often stayed in Antwerp. Among his pupils was Philip Rubens, brother of the painter Peter Paul Rubens who portrayed Lipsius after his death in ‘The Four Philosophers’ (c. 1611, now in the Pitti Palace, Florence). Among his admirers was Michel de Montaigne who described him as one of the most learned men then alive (Essais 2.12).

3. Works

Lipsius was a prolific author, publishing his first work Variarum Lectionum Libri IV (‘Four Books of Various Readings’) – a collection of philological comments and conjectures – in 1569, while still in his twenties. His reputation today is primarily as a Latin philologist and stands upon his critical editions of Tacitus and Seneca. He also produced a number of philological studies and a large correspondence, some of which he published. His principal philosophical works are De Constantia Libri Duo and Politicorum sive Civilis Doctrinae Libri Sex, complementing his editions of Seneca and Tacitus respectively.

a. Politicorum sive Civilis Doctrinae Libri Sex

In his Politicorum sive Civilis Doctrinae Libri Sex (‘Six Books on Politics or Civil Doctrine’) Lipsius drew upon a wide range of classical sources, with a particular emphasis upon Tacitus, and the work has been characterized, not unfairly, as not much more than a compendium of quotations. In it he argued that no State should permit more than one religion within its borders and that all dissent should be punished without mercy. Experience had taught him that civil conflict enflamed by religious intolerance was far more dangerous and destructive than despotism.

The treatise is concerned with the creation of civil life, defined as ‘that which we lead in the society of men, one with another, to mutual commodity and profit, and common use of all’ (Pol. 1.1). Such a life has two necessary conditions, virtue (virtute) and prudence (prudentia). Book One is devoted to an analysis of these two conditions: virtue requires piety and goodness; prudence is dependent upon use and memory. Book Two opens by arguing that government is necessary for civil life and that the best form of government is a principality. Civil concord requires all to submit to the will of one. ‘Principality’ (principatus) is defined as ‘rule by one for the good of all’ (Pol. 2.3). For the Prince to achieve this he himself must have both virtue and prudence. The remainder of Book Two is devoted to princely virtues, the most important being justice and clemency. Book Three moves on to consider princely prudence, and this remains the theme for the rest of the work. There are two types of prudence, one’s own and the advice of others. Book Three focuses upon prudent advisors in the form of counsellors and ministers. Book Four is concerned with a Prince’s own prudence, which must be carefully developed in the light of experience. This itself may be divided into civil and military prudence. The rest of Book Four outlines two types of civil prudence, that concerned with matters divine and that concerned with matters human. Military Prudence is the subject of Books Five and Six. Book Five deals with external military prudence (war with foreign powers), while Book Six deals with internal military prudence (civil war).

The central theme of the work is clear from the outset. Lipsius – pre-empting Hobbes – places order and peace far above civil liberties and personal freedom. Individual political rights are little consolation when surrounded by violent anarchy. The first task for politics is to secure peace for all and this can only be done if power is concentrated in one individual. It can also only be achieved if only one religion is allowed in any particular State. If one has concerns about such a concentration of power, the proper way to reduce them is to educate the holder of power, to develop his virtue and prudence, and to remind him that he holds power in order to secure peace, not to create terror. If a Prince forgets this last point and turns into a tyrant, there may be grounds to challenge his position. However Lipsius emphasizes that there is nothing more miserable than civil war which should be avoided at all costs.

b. De Constantia Libri Duo

Lipsius’s principal philosophical work is De Constantia Libri Duo (‘Two Books on Constancy’), published in 1584. The title is borrowed from Seneca’s dialogue De Constantia Sapientis. This work was immensely popular and went through numerous editions. It was translated into English four times between 1594 and 1670. It for this work that Lipsius became famous in the succeeding centuries, inspiring the intellectual movement that has come to be known as Neostoicism. This work was conceived as an attempt to revive Stoic philosophy as a living movement as it had been in antiquity and, in particular, as a practical antidote to public evils.

i. Form

The work takes the form of a dialogue between Lipsius and his friend Langius (Charles de Langhe, Canon of Liège). This no doubt fictional conversation is set within the context of a visit to Langius by Lipsius during the course of a trip to Vienna that Lipsius had actually undertaken in 1572. While some distance from his troubled homeland, the dialogue’s character Lipsius reflects upon the nature of public evils (mala publica) and is guided by the older and wiser Langius into whose mouth the positive content of the dialogue is placed.

ii. Analysis of Contents

The dialogue is divided into two books. However a single structure operates throughout the entire work. The opening chapters of Book One introduce the idea that in order to escape public evils one must change one’s mind, not one’s location (Const. 1.1-3). The concept of constancy is introduced as that which must be cultivated in the mind in order to achieve such a change (Const. 1.4-7). After a brief survey of the enemies of constancy (Const. 1.8-12), the four central arguments of the work, concerning the nature of public evil, are introduced (Const. 1.13). The first two of these arguments occupy the remainder of Book One (Const. 1.14 and 15-22). After a brief interlude at the beginning of Book Two on the nature of the philosophical project at hand (Const. 2.1-5), the remaining two arguments follow (Const. 2.6-17 and 18-26). The final chapter functions as a summary (Const. 2.27).

iii. Definition of constantia

The central concept in this work is, not surprisingly, constancy (constantia). It is introduced in Const. 1.4 and defined as a right and immovable strength of mind, neither elated nor depressed by external or chance events. The mother of constancy is patience (patientia), defined as a voluntary endurance without complaint of all things that can happen to or in a man.

However key to both of these concepts is the distinction between reason (ratio) and opinion (opinio). While opinion leads to inconstancy, it is reason that is able to form the foundation for constancy. Cultivating reason is thus the way in which one can reach the goal of constancy. Here Lipsius draws upon relatively common Stoic ideas concerning the passions or emotions (affectus; in Greek, pathê). Emotions are the product of mere opinions and lead to distress and imbalance. Analysing and rejecting those opinions in favour of rational understanding will free one from emotions and thus the inconstancy that they create. The wise man who enjoys constancy will be free from emotions such as desire (cupiditas), joy (gaudium), fear (metus), and sorrow (dolor).

iv. Four Arguments Concerning Public Evils

The core of De Constantia is the series of four arguments concerning the nature of public evils. These are outlined in Const. 1.13 and then developed, in turn, in Const. 1.14, 1.15-22, 2.6-17, and 2.18-26. It is argued that public evils are (a) imposed by God; (b) the product of necessity; (c) in reality profitable to us; (d) neither grievous nor unusual.

The first argument claims that all public evils form part of God’s divine plan. They derive form the same source as all those profitable parts of nature and it would be impious to take only part of God’s creation and criticise Him for the remainder. We are born into God’s creation and it is our duty to obey Him by accepting all of His works. In any case, even if one does not follow God’s will freely, one will nevertheless be drawn along forcibly (echoing the famous Stoic donkey and cart analogy reported in Hippolytus Refutatio 1.21). Thus the only option is to obey God (deo parere).

The second argument claims that the continual cycle of creation and destruction are the inevitable consequence of the necessary laws of Nature. If even the stars in the heavens are subject to the processes of creation and destruction, then it is only natural that man-made cities will rise and fall, for “all things run into this fatal whirlpool of ebbing and flowing” (Const. 1.16). However Lipsius is careful here to distance himself from Stoic materialism and outlines four points where Stoic doctrine must be modified in the light of Christian truth (see the next section).

The third argument is merely a variation upon traditional Christian responses to the problem of evil. Those terrible things that happen must in some sense be good if they are part of God’s divine plan and Lipsius attempts to show this by claiming that public evils constitute exercise (exercendi) for the good, correction (castigandi) for the weak-willed, and punishment (puniendi) for the bad.

The fourth argument focuses upon the particular public evils that Lipsius wanted to avoid, namely the religious civil wars in the Low Countries. He argues that these wars are neither particularly grievous nor uncommon. In order to place these present conflicts into perspective Lipsius, drawing upon his extensive classical learning, cites numerous examples of wars, plagues, and acts of cruelty from Jewish, Greek, and Roman history. The conflict from which Lipsius has fled is neither excessively brutal nor particularly unusual. What would be unusual would be an individual insulated and exempted from the cycles of birth and death, creation and destruction. It is the human lot to suffer at the hands of this continual change; the philosophical task, however, is to decide how one will face that suffering. One can do so either with sorrow (dolor) or with constancy (constantia).

v. Four Modifications of Ancient Stoicism

During the course of the second argument concerning the nature of public evils, Lipsius outlines four points where Stoicism and Christianity diverge. He is careful to distance himself from these parts of Stoic philosophy and the modification of Stoicism that he makes here (Const. 1.20) in order to reconcile it with Christianity forms the basis for the intellectual movement that has come to be known as Neostoicism. The four points in question are the Stoic claims that (a) God is submitted to fate; (b) that there is a natural order of causes (and thus no miracles); (c) that there is no contingency; (d) that there is no free will. All four of these points derive from the Stoic theory of determinism and it is this to which Lipsius primarily objects.

Stoic determinism is itself built upon Stoic materialism, which affirms that only bodies exist. These bodies act as causes and so anything that acts, including the soul, must be corporeal. Aulus Gellius reports that the Stoic Chrysippus defined fate as a natural and everlasting order of causes in which each event follows from another in an unalterable interconnection (Noctes Atticae 7.2.3). Thus, as Cicero notes, the Stoic doctrine of fate, conceived as an order and sequence of material causes, is “not the fate of superstition but rather that of physics” (De Divinatione 1.126). By rejecting this doctrine, Lipsius attempts to disengage the Stoic ethical ideas to which he is drawn from their foundations in Stoic physics. This is absolutely essential if he is to be able to present Stoic ethics in a form acceptable to a Christian audience.

vi. Summary

The central theme of De Constantia – that public evils are the product of the mind and thus must be treated rather than fled – contrasts sharply with Lipsius’s own earlier behaviour when faced with the religious wars then raging. Perhaps experience had taught him that, no matter how many geographical moves he made, he would not be able to escape the evils surrounding him until he examined himself. Only wisdom and constancy – the products of philosophical reflection – can bring true peace of mind.

c. Later Stoic Works

De Constantia was not Lipsius’s only work devoted to Stoicism. He also produced two studies of Stoic philosophy during the course of the preparation of his 1605 edition of Seneca; the Manuductio ad Stoicam Philosophiam (‘Digest of Stoic Philosophy’) and the Physiologia Stoicorum (‘Physics of the Stoics’), both published in 1604. These works offer an interpretation of every aspect of Stoic philosophy and draw together under subject headings large numbers of quotations and doxographical reports preserved in a wide range of ancient authors. These two works may be seen as the precursors to the, now standard, edition of the fragments of the early Stoics compiled by Hans von Arnm (Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta, 1903-24).

These later studies of Stoicism – based upon a more systematic survey of the surviving sources – are marked by two features which distinguish them from De Constantia. The first is a more developed awareness of the systematic inter-relation between ethics and physics in Stoic philosophy; the second is a revised and more positive attitude towards the Stoic theory of determinism. In Phys. 1.12, for instance, Lipsius demonstrates a more thorough understanding of the Stoic theory of fate, and on the basis of this he suggests that it can in fact be reconciled with Christian doctrine without modification. In order to do this, he draws upon St. Augustine’s discussion of Stoic definitions of fate in De Civitate Dei 5.8 where it is argued that fate does not impinge upon the power of God but rather is the expression of the will of God.

While De Constantia was a popular and highly readable dialogue, these later studies were primarily works of classical scholarship. They were conceived as supplementary volumes designed to complement – and perhaps even justify – Lipsius’s final great work, his 1605 critical edition of the philosophical works of Seneca. This handsome folio edition included all of Seneca’s prose works, detailed summaries for each, commentary, and a biography of the great Roman Stoic. In this final publication, Lipsius’s admiration of Stoic philosophy and his talents as a classical philologist are united so as to form a highly appropriate culmination to his intellectual career.

4. Conclusion

Lipsius has been described as the greatest Renaissance scholar of the Low Countries after Erasmus. The role that he played in the revival of interest in Stoicism during the late Renaissance was similar to that performed by Marsilio Ficino with regard to Platonism and Pierre Gassendi with regard to Epicureanism. As such, he stands as a key figure in the history of Renaissance philosophy and the Renaissance revival of ancient thought.

5. References and Further Reading

a. The Works of Justus Lipsius

All of Lipsius’s works are gathered together in his Opera Omnia of 1637. Another edition appeared in 1675. Full bibliographical details for all of his works can be found in F. Van Der Haeghen’s Bibliographie Lipsienne: Oeuvres de Juste Lipse, 2 vols (Ghent: Université de Gand, 1886).

i) Politicorum sive Civilis Doctrinae Libri Sex

- Politicorum sive Civilis Doctrinae Libri Sex (Leiden: Plantin, 1589) – the first edition.

- Sixe Bookes of Politickes or Civil Doctrine, Done into English by William Jones (London: Richard Field, 1594) – there is also a facsimile reprint of this edition (Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1970).

ii) De Constantia Libri Duo

- De Constantia Libri Duo, Qui alloquium praecipue continent in Publicis malis(Antwerp: Plantin, 1584) – the first edition.

- Traité de la constance, Traduction nouvelle précédée d’une notice sur Juste Lipse par Lucien du Bois (Brussels & Leipzig: Merzbach, 1873) – still the most recent edition of the Latin text, with a facing French translation.

- Two Bookes of Constancie Written in Latine by Iustus Lipsius, in English by Sir John Stradling, Edited with an Introduction by Rudolf Kirk (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1939) – the most recent edition in English, reprinting a translation first published in 1594.

iii) Later Stoic Works

- Manuductionis ad Stoicam Philosophiam Libri Tres, L. Annaeo Senecae, aliisque scriptoribus illustrandis (Antwerp: Plaintin-Moretus, 1604) – extracts reprinted and translated into French in Lagrée (below) – extracts also translated into English in J. Kraye, ed. Cambridge Translations of Renaissance Philosophical Texts 1: Moral Philosophy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 200-09.

- Physiologiae Stoicorum Libri Tres, L. Annaeo Senecae, aliisque scriptoribus illustrandis (Antwerp: Plantin-Moretus, 1604) – extracts reprinted and translated into French in Lagrée (below).

- Annaei Senecae Philosophi Opera, Quae Existant Omnia, A Iusto Lipsio emendata, et Scholiis illustrata (Antwerp: Plantin-Moretus, 1605) – Lipsius’s ‘Life of Seneca’ and his summaries are translated by Thomas Lodge in his The Workes of Lucius Annaeus Seneca (London: William Stansby, 1620), which is based upon Lipsius’s edition.

b. Studies

- ANDERTON, B., ‘A Stoic of Louvain: Justus Lipsius’, in Sketches from a Library Window (Cambridge: Heffer, 1922), 10-30.

- GERLO, A., ed., Juste Lipse (1547-1606), Travaux de l’Institut Interuniversitaire pour l’étude de la Renaissance et de l’Humanisme IX (Brussels: University Press, 1988)

- LAGRÉE, J., Juste Lipse et la restauration du stoïcisme: Étude et traduction des traités stoïciens De la constance, Manuel de philosophie stoïcienne, Physique des stoïciens (Paris: Vrin, 1994)

- LAGRÉE, J. ‘Juste Lipse: destins et Providence’, in P.-F, Moreau, ed., Le stoïcisme au XVIe et au XVIIe siècle (Paris: Albin Michel, 1999), 77-93.

- LAGRÉE, J. ‘La vertu stoïcienne de constance’, in P.-F, Moreau, ed., Le stoïcisme au XVIe et au XVIIe siècle (Paris: Albin Michel, 1999), 94-116.

- LAUREYS, M., ed., The World of Justus Lipsius: A Contribution Towards his Intellectual Biography, Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome LXVIII (Brussels & Rome: Brepols, 1998)

- LEVI, A. H. T., ‘The Relationship of Stoicism and Scepticism: Justus Lipsius’, in J. Kraye and M. W. F. Stone, eds, Humanism and Early Modern Philosophy (London: Routledge, 2000), 91-106.

- MARIN, M., ‘L’influence de Sénèque sur Juste Lipse’, in A. Gerlo, ed., Juste Lipse: 1547-1606 (Brussels: University Press, 1988), 119-26.

- MORFORD, M., Stoics and Neostoics: Rubens and the Circle of Lipsius (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991)

- MORFORD, M. ‘Towards an Intellectual Biography of Justus Lipsius – Pieter Paul Rubens’, Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome 68 (1998), 387-403.

- OESTREICH, G., Neostoicism and the Early Modern State, trans. D. McLintock (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982)

- SAUNDERS, J. L., Justus Lipsius: The Philosophy of Renaissance Stoicism (New York: The Liberal Arts Press, 1955)

- ZANTA, L., La renaissance du stoïcisme au XVIe siècle (Paris: Champion, 1914)

References to further works dealing with Neostoicism may be found at the end of the IEP article Neostoicism.

Author Information

John Sellars

Email: john.sellars (at) wolfson.ox.ac.uk

University of the West of England

United Kingdom