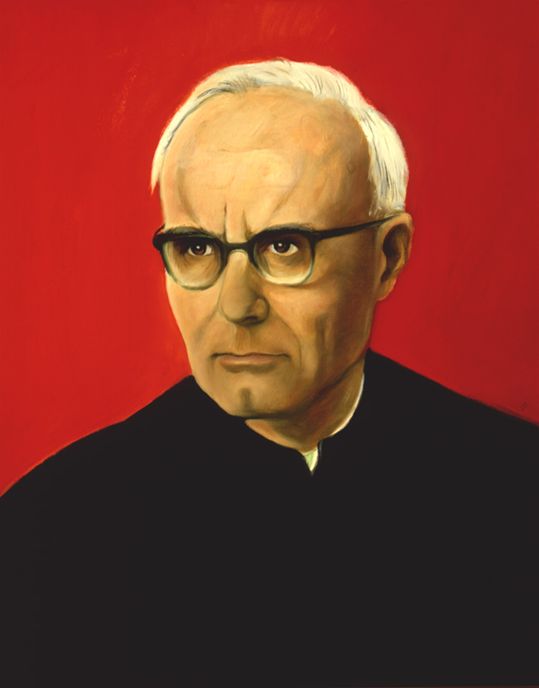

Karl Rahner (1904-1984)

Karl Rahner was one of the most influential Catholic philosophers of the mid to late twentieth century. A member of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) and a Roman Catholic priest, Rahner, as was the custom of the time, studied scholastic philosophy, through which he discovered Thomas Aquinas. From Aquinas’ epistemology and philosophical psychology Rahner was introduced to the Aristotelian-Thomistic notion of abstraction. This theory holds that human beings, as embodied souls or spirits, directly know only that which is sensed; direct sensory knowledge is physical knowledge. The intellect, through complex actions best described as abstraction, draws from sensory knowledge. This knowledge is indirect but valid knowledge of spiritual or non-physical realities. Thus, Rahner, learning from Thomas, held that it is the abstractive power of the mind that leads to indirect knowledge of the spiritual. Kant led Rahner to the philosophical work of Joseph Maréchal, a fellow Jesuit. Maréchal attempted to use Kant to create a re-vitalized Thomism. Maréchal held that the dynamic of the mind transcends the dichotomy of phenomenon and noumenon by attaining the utter unity of the Absolute. Rahner learned from Maréchal that the Kantian frustration could be overcome by the dynamic of the mind. Finally Rahner learned from Pierre Rousselot, another Jesuit, that the mind’s dynamic is drawn to the Absolute because the Absolute is the pure unity of being and spirit. So from Rousselot, Rahner understands the absolute terminus of the dynamic of mind to be the pure unity of being and spirit. It is from these strands that Rahner weaves his unique philosophical system.

Karl Rahner was one of the most influential Catholic philosophers of the mid to late twentieth century. A member of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) and a Roman Catholic priest, Rahner, as was the custom of the time, studied scholastic philosophy, through which he discovered Thomas Aquinas. From Aquinas’ epistemology and philosophical psychology Rahner was introduced to the Aristotelian-Thomistic notion of abstraction. This theory holds that human beings, as embodied souls or spirits, directly know only that which is sensed; direct sensory knowledge is physical knowledge. The intellect, through complex actions best described as abstraction, draws from sensory knowledge. This knowledge is indirect but valid knowledge of spiritual or non-physical realities. Thus, Rahner, learning from Thomas, held that it is the abstractive power of the mind that leads to indirect knowledge of the spiritual. Kant led Rahner to the philosophical work of Joseph Maréchal, a fellow Jesuit. Maréchal attempted to use Kant to create a re-vitalized Thomism. Maréchal held that the dynamic of the mind transcends the dichotomy of phenomenon and noumenon by attaining the utter unity of the Absolute. Rahner learned from Maréchal that the Kantian frustration could be overcome by the dynamic of the mind. Finally Rahner learned from Pierre Rousselot, another Jesuit, that the mind’s dynamic is drawn to the Absolute because the Absolute is the pure unity of being and spirit. So from Rousselot, Rahner understands the absolute terminus of the dynamic of mind to be the pure unity of being and spirit. It is from these strands that Rahner weaves his unique philosophical system.

Table of Contents

1. Life

Karl Rahner was born 5 March 1904 in the university town of Freiburg-im-Breisgau in the then Grand Duchy of Baden, the fourth of seven children. His father Karl was an educator; his mother Luise, a homemaker. Rahner’s mother was pious, but in a healthy sense: the atmosphere of a university town imbued that piety with openness. It can therefore be said that Rahner’s childhood laid the groundwork for his later complex philosophical and theological projects: a pious openness, seeking the most effective formulations to gain insight into the character of the world.

At age eighteen, on 20 April 1922, Karl Rahner entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus. The Jesuits had been, since their inception, an intellectual religious congregation: among their number were philosophers such as Francisco Suárez; nascent biologists such as Athanasius Kircher, discoverer of microbes; missionary-linguists such as Matteo Ricci; paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and cosmologist George LeMa”tre. It was thus the perfect environment in which Rahner might begin to develop his own thought: intellectually rigorous, pioneering, open.

After the completion of novitiate and the taking of vows Rahner entered the scholasticate, the formal program of studies. These studies were founded upon the current Neo-Scholastic manuals, much defamed but actually thorough presentations of Scholastic thought. Rahner was deeply influenced by Aquinas, of course; Aquinas had been mandated by Leo XIII as the Catholic philosopher. At the same time Rahner discovered three of the four major influences that would form his intellectual horizons: Immanuel Kant and fellow Jesuits Pierre Rousselot and Joseph Maréchal. It was, however, Maréchal, and Maréchal’s interpretation of Kant, who became the decisive impetus to Rahner’s ongoing philosophical reflections.

Rahner’s superiors soon noted the caliber of his intellect, and so he was sent to the University of Freiburg in Freiburg-im-Breisgau, his home, to begin doctoral studies in philosophy in 1934: his superiors foresaw for him a university career as a professor of philosophy. It was at Freiburg where Rahner, despite his sincere acknowledgements of the importance of Aquinas, Kant and especially Maréchal, discovered the philosopher whom he would later call his true teacher: Martin Heidegger. Until his death Rahner kept with him the list of courses he had taken with Heidegger. Heideggerian thought became the catalyst through which the transcendental philosophies of Kant, and especially Kant through Maréchal, began to coalesce into the Rahnerian philosophical system. In 1936, Rahner submitted his doctoral thesis, Geist in Welt, usually rendered Spirit in the World, which attempts a radical re-reading of Aquinas through Kant, Maréchal and Heidegger. Geist in Welt was essentially a lengthy gloss on a single question in Thomas’ Summa, an intricate, complicated, tightly woven, and impenetrable Maréchallian-Heideggerian interpretation. It was rejected as being too influenced by Heidegger. That same year Rahner was transferred to Salzburg to study theology, gaining a doctorate there.

Rahner then began his university career in 1937 at the University of Innsbruck. In that same year Rahner gave a series of lectures at Innsbruck; these became the basis for Rahner’s last purely philosophical work, his philosophy of religion and revelation, Hšrers des Wortes (Hearers of the Word).

During the war years and post-war years, 1939-1949, Rahner engaged in pastoral work in Vienna. After the war he returned to Innsbruck in 1949 and began to develop his theological system, a system rooted completely in the metaphysics of Geist in Welt and Hšrers des Wortes: human beings, finite, yet invested by an infinite and inexhaustible epistemological dynamic, are intrinsically open to the revelation of the utter mystery that is God. Thus religion is the thematization of the absolutely unthematic.

While at Innsbruck in 1962 Rahner’s superiors received a monitum from the Holy Office in Rome: Rahner was neither to lecture nor publish without Rome’s explicit permission. The irony: in that same year Pope John XXIII named Rahner a peritus to the Second Vatican Council. Rahner’s influence was profound; it was Rahner who was the principal behind the drafting of Lumen Gentium, The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church. The monitum, obviously, disappeared into bureaucratic oblivion. Rahner taught at Innsbruck until 1964. From 1964 until 1981 Rahner taught at the University of Munich. Rahner retired to Innsbruck, where he died, 30 March 1984. Karl Rahner was, and remains, a powerful influence upon the Roman Catholic Church. Rahner’s philosophy was at once the foundation and framework for his far-reaching and in some ways radically different re-reading of Roman Catholic dogma. It is important to note, however, that Rahner’s philosophical system precedes and is separable from the theological system built upon it.

2. Influences

In summary: Rahner derived the notion of the transcendental structure of knowledge from Kant, and from Rousselot and Maréchal he derived the notion of the infinite dynamic inherent in this transcendental structure. This infinite dynamic possesses an intrinsic inevitability toward the Absolute or God. Because of his exposure to Heidegger’s system of thought, Rahner ultimately came to characterize human beings as utterly finite yet as ever ordered to being.

a. Kant

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) brought to crescendo the “philosophy of the subject” that had been steadily on the rise from time of the great Scholastics. For Kant an authentic subjectivity, one that at once addressed the real, however unknowable (the noumenal), and from that address structured the known (the phenomenal), was the only answer to the radical skepticism of Hume. It was in response to this skepticism that Kant created his great work, Kritik der Reinen Vernunft (Critique of Pure Reason) in two editions: the first (A) in 1781, the second, greatly expanded edition (B), in 1787. The Kritik was the impetus for Joseph Maréchal to establish Transcendental Thomism, which, in turn, decisively influenced Rahner. This is the central concern of the Kritik: how can one gain certitude? How, in the face of radical skepticism, can one be sure of the world? Simply put, is knowledge possible, and, if so, what is the guarantee of that knowledge? Kant reasoned that the facticity of this or that experience is formed within a grid of pre-determined schemata, and from this application there emerges consistent, verifiable and, thus, dependable knowledge. These schemata are the a priori structures of reason. These a priori structures, the categories, render that which is experienced globally consistent and temporally consistent. The categories, the a priori structures of reason, are therefore frameworks to which the to-be-known must conform to be known. Thus, Kant finds the consistency and dependability of knowledge in the constant a priori schemata or categories proper to reason as reason. Kant was fully satisfied that he had established a lasting guarantee of the certainty of knowledge. Joseph Maréchal, with Heidegger serving as the decisive influence upon Rahner’s philosophical thought, would serve as mediator between Kant and Rahner. It is through Maréchal’s system that transcendental idealism is married to Aquinas’ Aristotelian epistemology. The mind, dynamic in its address of that which is to be known, structures the known through abstraction, but this abstraction is a neo-Kantian impetus to the Absolute or God.

b. Rousselot

Pierre Rousselot (1878-1915) was ordained in England in 1908. Remarkably (and in significant demonstration of his intellectual capabilities) Rousselot completed his theological preparations for ordination while simultaneously earning the customary two doctorates from the Sorbonne in 1908, the year of his ordination: the major thesis, L’intelletualisme de saint Thomas, and the minor thesis, Pour l’historie du problem de l’amour au Moyen Age. In L’intellectualisme Rousselot created an entirely unique Neo-Thomist system, one he styled as a Platonized Thomism. The entire system hinges on the identification of spirit and being in divinity as the very nature of the Godhead. This was an attempt at a defensible interpretation of Thomas. The unity of spirit and being that is God is thus the self-knowing of God as his being: in other words, God is infinite intelligibility utterly transparent in pure self-possession. Rousselot takes this as his model for all forms of knowledge. Rousselot holds that every act of comprehension, of understanding, as the discovery and appreciation of intelligibility, is in fact an affirmation of the existence of the God which is pure intelligibility. From Rousselot, Rahner came to appreciate the identity of spirit and being, and thus the intrinsic intelligibility of all which, when realized in the act of intellection, requires the co-affirmation of the existence of God. Rahner learned from Rousselot that knowing strengthens the relation to the Absolute. For Rahner the mind is an organ of the affirmation of divinity. It was Rousselot who opened Rahner to Maréchal.

c. Maréchal

Maréchal and Heidegger were the decisive influences upon Rahner’s thinking. Joseph Maréchal was a contemporary of Rousseolt, but although there was productive dialogue between the two, Maréchal pursued a deliberately Kantian path. Joseph Maréchal (1878-1944) entered the Society of Jesus in 1895 and while in England during the Great War he began work on his system, explicated in the five volume opus Le Point du Départ de la Métaphysique: Leçons sur le Développment Historique et Théorique du Problème de la Connaissance (henceforward simply Le Point du Départ de la Métaphysique). MMaréchal sought in these five volumes to trace the history of western philosophy and describe what he thought to be the true philosophical system: a Thomism rethought in the light of Kant.

It is the fifth volume of Le Point du Départ de la Métaphysique, titled Le Thomisme devant la Philosophie Critique, that deeply influenced Rahner. Maréchal appreciates Kant’s notion that the mind is an active and dynamic structuring of that which it knows. However, he believes that Kant fails to honor the character of this dynamic. Thus, Maréchal sees the dynamic as twofold. First, it is the dynamic openness of the mind, for the mind seeks to grasp all it encounters. Second, the dynamic of the mind is invested with an intrinsic direction to a specific end. The dynamic of the mind, investing all that can be known, structuring the knowable to the known, is quite literally driven to an end (in Maréchal’s scholastic vocabulary, it is possessed of an irresistible “finality”) which is its ultimate goal. Maréchal argues that Kant does not appreciate the power of mind he has discovered. Maréchal sees that the Kantian transcendental dynamic, the mind structuring the knowable to the known, must ultimately terminate in absolute being. Maréchal holds that the dynamic, searching, structuring character of the mind will structure everything knowable to the known. This Kantian impetus is ultimately rooted in its trajectory toward the absolute, toward the absolute as absolute being in which absolute being is absolute truth. For Maréchal, as for Rousselot, every act of knowing is at once an implicit affirmation of the absolute that is absolute being as absolute truth. Here Rahner found the means to go beyond Kant and give systemic form to Rousseolt’s lyrical Platonized Thomism: Maréchal gave to Rahner the Thomist framework to both appropriate Rousselot’s themes of the identity of spirit and being in the pure intelligibility that is God and the utter dynamic of human knowing grounded in that identity.

d. Heidegger

It was Heidegger who was perhaps the greatest influence on Rahner. It is the marriage of Heidegger’s thinking to that of Maréchal’s that joins Heideggerian finitude as open-ness to being-as-irreducible to the Maréchallian dynamism of knowing intrinsically ordered to the Absolute. This move firmly established the foundation of Rahner’s philosophical system. Martin Heidegger’s (1889-1976) Sein und Zeit is the final and decisive influence on Rahner. Its themes, melded with those of Maréchal, give the cast to Rahner’s thought. The animating principle and overarching motif of Sein und Zeit is being or being at its most irreducible. In it Heidegger seeks to discover, amongst and through and beneath the myriad kinds of beings, that uttermost manner of being-ness that underlies this myriad. To discover this being-most-irreducible it is necessary to seek this being, and it is human beings who seek being-most-irreducible. Heidegger calls this being Dasein: literally, being-there, being-emplaced, being-in-and-of-the-world-of-beings. Dasein puts being-most-irreducible in question when it gives itself over to the mystery that is being-most-irreducible. Dasein becomes the possibility of being-most-irreducible revealed as it is. But how, then, does Dasein in its questioning quest reveal being-most-irreducible? Only in the authenticity of Dasein: being authentic. How does Dasein be-authentically? Through Dasein’s realization of its utter finitude. And how is finitude disclosed to Dasein? When Dasein as being-authentically accepts being-toward-death. The complete acceptance of death, the radical finitude of being, opens Dasein to being-most-irreducible, for radical finitude recognizes that which is most irreducible as the reply to that finitude. Rahner neatly synthesizes Maréchal’s dynamic of mind inevitably ordered to absolute being with Heidegger’s notion of Dasein.

e. Summary

It is through Maréchal that Rahner understands Kant and Maréchal’s notion of the dynamic of mind thrusting to the absolute being. This becomes the core of Rahner’s system. Rousselot provides the inspiration in the identity of spirit and being in knowing, and Heidegger’s thinking brings this together. The dynamic thrust of the knowing mind understands the being-most-irreducible as God and the unity of being and spirit in knowing. God is implicitly and intrinsically affirmed in the dynamic of every act of knowing. Thus, through Maréchal Rahner appropriates the Kantian notion of the transcendental structuring of the known by the mind. Through Rousselot and most especially Maréchal, Rahner sees this structuring of the known as a drive to attain the Absolute or God, and it is through Heidegger that this drive is rooted in radically finite human beings, and he discloses God as the identity of spirit and being.

3. Rahner’s System

Rahner’s system is fully explicated in Geist in Welt. Here the foundation is meticulously and densely established. Rahner’s second work, Hšrers des Wortes, forwards a system whereby the human and the divine are intrinsically ordered one to the other. For Rahner, human being as defined in Geist in Welt is intrinsically open to God or the Absolute. It is necessarily the receptacle of revelation. In Rahner’s view even if God or the Absolute remains utterly silent and completely hidden that silence and hiddenness, are, in fact, revelations.

a. Geist in Welt

Translating Geist in Welt as Spirit in the World demonstrates Rahner’s dense use of language. Geist qua spirit denotes both spirit as the unity of being and spirit as known and knowing in human reason, as demonstrated in the thinking of Rousselot. The preposition in does not simply note location but it is also indicative of a movement-towards; Welt is the Heideggerian welt, the world as the location of Dasein as the arena of the quest for Being-most-irreducible. Geist in Welt is remarkably simple in concept and extraordinarily complex in execution. It takes a single question and a single article from Thomas’ Summa Theologiae (ST) and uses them as the fulcrum to erect the Rahnerian synthesis. The question: ST I, q 84, a 7; seven hundred words devoted to the crux of Thomastic psychology and epistemology become the cornerstone of Rahner’s philosophical system.

Thomas notes that in this life the soul is joined to its body; it is through the physicality of its body that the soul interacts with the world. Thomas, following his master Aristotle, holds that the intellect (mind) cannot directly know what the body senses and perceives. The mind is spirit, the body matter. Keep in mind Thomas is not a dualist like Descartes; soul and body, spirit and matter are united, wholly interactive and completely congruent. However a transition from the sensed and the perceived to the known is necessary for Thomas. This transition occurs within the process of intellection (the process of the mind coming to understanding). Thomas, in a manner reminiscent of Kant, also holds that the mind does not directly know the world. Thomas did not see the mind possessing a priori structures. Rahner introduces a Kantian a priori thematic through Maréchal into Thomas. Thomas sees that there is a meditative structure to knowing and this mediation occurs in the following sequential constellation. The imagination receives the impressions of the experienced from the senses and the imagination creates an image of that which is experienced or the phantasm. The phantasm is received by the active (or agent) intellect, which abstracts from the phantasm the universal(s) proper to the object(s) experienced, and thus contained in the phantasm is this intelligible species. The passive (or possible) intellect receives the intelligible species and renders it to the verbum mentis, the “mind’s word,” which is the achieved comprehension and attained understanding.

So like Kant, Thomas does not believe human beings directly experience the world as it is; unlike Kant, there are no categories to structure the perceived world as understood. Rather there is a complex translation of the perceived (which is of the body) to the understood (which is of the soul). It is important to remember that Thomas insists human beings cannot know through their spiritual essence (here the soul) as do the angels. Human beings are of the world and so all human knowledge is the result of mediation and translation. It is this thematic that Rahner appropriates as the jumping off point of Geist in Welt and it is also this thematic that, through Maréchal and Heidegger, becomes the very core of Rahner’s philosophical system. Rahner begins with the process of abstraction which is the work of the agent intellect upon the phantasm. Rahner, along with Thomas, notes the world is the arena of the metaphysical. It is in and through the world that human beings through their agent intellect encounter and grasp thematically being-most-irreducible and also the unthematically present absolute being, God.

Thus: esse—Thomas’ word for being-most-irreducible—is, via Rahner, now the woauf of the Vorgriff, which is of the agent intellect. Woauf, a compound of prepositions, means: wo, where or how; auf, toward, up to, into. Thus, woauf might be rendered, however ungrammatically, as “potential-toward.” Vorgriff is another Rahnerian coinage: vor means before, previous, ahead; and greifen (from which griff is derived) means seize, grasp, hold or comprehend. Thus the Vorgriff is that prior projectedness to comprehension. Thus esse, grasped by the agent (active) intellect, is the potential toward which the prior projectedness to comprehension is directed. It is the Vorgriff, the projectedness to comprehension (as grasping, seizing), that is key to Rahner’s system. The Vorgriff bounds and compasses being-most-irreducible. It is at once, however, non-objective in this bounding and compassing. The Vorgriff is the condition of all knowing and the Vorgriff, as the bounding and compassing of being-most-irreducible, is a directedness to the absolute being, God, which is the ground of being-most-irreducible.

It is this Vorgriff that is the condition or possibility of the knowing of all objective beings. Indeed, all objective beings, and all possible objects of knowledge, are of the index of being that is the Vorgriff. The passive (possible) intellect is the self-becoming of human beings as knowing beings. Receiving the verbum mentis, which is the appropriation of the endless scope of the Vorgriff of the agent (active) intellect, the passive intellect is therefore the human spirit as identity of being and spirit. The passive intellect realizes through the active intellect the utterness of being-most-irreducible. The passive intellect becomes all beings as rendered knowable by the agent intellect through the Vorgriff. It is the full scope of being as spirit being as known which is the dynamic of the human mind encompassing being-most-irreducible. The human spirit directed toward being-most-irreducible through the Vorgriff as the potential prior-directedness to comprehension of being-as-irreducible. In turn the being-as-irreducible is constituted human as both the identity of spirit and being in the mind knowing all possible beings because it becomes all beings rendered knowable. Through this occurs the revelation of absolute being, God. This is the knowing of absolute being as last-knowable-being but knowable only in its infinitely distant obscurity. Geist in Welt blends the following: 1.) Maréchal: the themes of dynamism; 2.) the co-affirmation of absolute being with the grasp of being-most-irreducible and all possible beings to be known in the act of knowing of the human being; 3.) Heidegger’s themes of being-most-irreducible; 4.) Dasein as unformed and thus the self-constituting embeddedness of human being in the world and 5.) the world and the beings of the world as the means to discover being-most-irreducible.

b. Hšrers des Wortes

In Hšrers des Wortes Rahner restates, more lucidly, his themes from Geist in Welt. Recasting these themes in terms of metaphysics, Rahner notes that metaphysics addresses the question of being as being-most-irreducible. Metaphysics formulates the question to the beingness of beings to being-most-irreducible. The question of the beingness of beings, being-most-irreducible, addresses the ground of this beingness, this being-most-irreducible. These questions arise because of the ultimate unity of being and being-known. Rahner called this unity of being and being known, in another neologism, Bei-sich-sein, being-present-to-itself. Beingness is analogical. There are degrees of being-present-to-itself as the unity of being and being known just as there are degrees of intensity of the self-presence, the unity. God is absolute being and therefore absolute being-present-to-itself. For Rahner God is the absolute unity of being and being-know, the absolute possession of beingness; therefore God is the ground of being-most-irreducible. Human being, through the Vorgriff, constitutes itself as the dynamic self movement of spirit, the identity of being and being-known-to the absolute compass of all possible beings-as-knowable.

This movement requires the co-affirmation of the absolute being, God, as the being characterized by absolute self-possession of being. God as God, the pinnacle of the analogy of being-present-to-itself, is the possibility of the Vorgriff. Thus, human being as spirit is the openness of the finite to god, the absolute infinite. Human being as spirit is the dynamic self-movement of transcendence to absolute being to God, and thus the possibility of the disclosure of this Absolute Being. The absolute being-present-to-itself that is God is correlated to human being as an endlessly dynamic self movement of transcendence and thus the analogy of being-present-to-itself in degrees of self-possession and the degrees of intensity of unities of being and being-known. This absolute transcendence of human being as spirit toward the infinity of beingness as the absolute self-presence of absolute being is the limitless compass of the Vorgriff. In addition, this same Vorgriff is the possibility of the appearance of the limitless God to limited human beings. The Vorgriff is not limitless in itself, but it is limitless in the endless dynamic of spirit. In this endless dynamic is the co-affirmation of absolute being in the limitless compass of the Vorgriff as it addresses all possible beings as knowable. Fundamentally, the Vorgriff is the awaiting of the disclosure of the absolute being present in that dynamism. Therefore, Rahner declares that this self-disclosure is inevitable and even the silence of refusal is disclosure of absolute being.

4. Summary

Rahner’s utterly unique reading of Thomas through Maréchal and Heidegger cost him his doctorate in philosophy at Freiburg. Yet Geist in Welt demonstrates the fecundity of Rahner’s mind. Taking a single question from the Summa and but a single article in that question, Rahner, using medieval epistemological categories, weaves Maréchal, Rousseolt, and Heidegger into a vibrant transcendental synthesis. Other Catholic philosophers remained closer to Maréchal, especially Francophone philosophers. These were the practitioners of Transcendental Thomism. Rahner’s philosophy forwards a unique transcendentalism from Thomism featuring 1.) the Heideggerian rootedness of human being in its world. This comprises the vast field of beings that is the medium through which being-most-irreducible is revealed; being-most-irreducible is the proper fulfillment of human being. 2.) The Rousselotian identity of knowing and being as spirit as the hierarchy of degrees of self-possession. 3.) The Maréchallian themes of the endless dynamism of mind and the intrinsic co-affirmation of absolute being in that dynamism. This is Rahner’s unique synthesis; it demonstrates the power of his mind as synthetic, the uniqueness of his insight to build this edifice on the alien foundation of medieval scholasticism, and the complexity and subtlety of his system-building skill.

5. References and Further Reading

a. Karl Rahner: Primary

- Karl Rahner, Geist in Welt, dritte auflage MŸnchen: Kosel, 1941

- Karl Rahner, Hšrers des Wortes, zweite auflage MŸnchen: Kosel, 1968

- Karl Rahner, Spirit in the World New York: Continuum, 1994

- Karl Rahner, Hearer of the Word New York: Continuum, 1994

b. Karl Rahner: Secondary

- Patrick Burke, Re-interpreting Rahner: A Critical Study of his Major Themes NY: Fordham, 2002

- Stephen Fields, Being as Symbol Washington DC: Georgetown, 2000

- Karen Kilby, Karl Rahner: Theology and Philosophy London: Routledge, 2003

- Thomas Sheehan, Rahner Athens OH: Ohio University Press, 1987

c. Immanuel Kant: Primary

Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Reinen Vernunft 1 & 2 (Bande III/IV, Werkausgabe in 12 Bande) Berlin: Suhrkamp, 1974

d. Pierre Rousselot: Primary

- Pierre Rousselot, L’intellectualisme de St. Thomas 2. ed Paris: Beauchesne, 1908

- Pierre Rousselot,The Intellectualism of St Thomas (translated, James Mahoney) New York: Sheed and Ward, 1935

- Pierre Rousselot, Intelligence: Sense of Being, Faculty of God (translated, Andrew Tallon) Marquette WI: Marquette University Press, 2002

e. Pierre Rousselot: Secondary

John McDermott, Love and Understanding Rome: Gregorian University, 1983

f. Joseph Maréchal: Primary

Joseph Maréchal, Le Point de Depart de la Metaphysique 5 volumes Paris: Desclee de Brouwer, 1922

g. Joseph Maréchal: Secondary

Anthony M. Matteo, Quest for the Absolute DeKalb IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1992

h. Martin Heidegger: Primary

- Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit zehnte auflage Tubingen: Max Niemeyer, 1963

- Martin Heidegger, Being and Time (translated, John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson) NY: HarperCollins, 2008

Author Information

Guy Woodward

Email: gwoodward127@gmail.com

U. S. A.