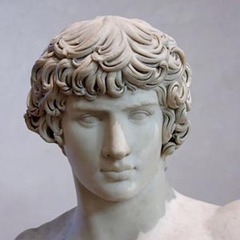

Critias (460—403 B.C.E.)

Critias, son of Callaeschrus, an Athenian philosopher, rhetorician, poet, historian, and political leader, was best known for his leading role in the pro-Spartan government of the Thirty (404-403 BC). But Critias also produced a broad range of works and was a noted poet and teacher in his own time. The fragments of three tragedies and a satyr play, a collection of elegies, books of homilies and aphorisms, a collection of epideictic speeches, and a number of constitutions of the city-states both in poetry and prose all have been passed down in the works of later authors. In spite of arguments over the authorship of certain works ascribed to him and the brevity of the fragments, few other classical Greek writers present such a breadth of literary output. Critias, the political figure, author, and philosopher, stands as one of the most controversial and enigmatic figures of fifth-century BC Athens.

Critias, son of Callaeschrus, an Athenian philosopher, rhetorician, poet, historian, and political leader, was best known for his leading role in the pro-Spartan government of the Thirty (404-403 BC). But Critias also produced a broad range of works and was a noted poet and teacher in his own time. The fragments of three tragedies and a satyr play, a collection of elegies, books of homilies and aphorisms, a collection of epideictic speeches, and a number of constitutions of the city-states both in poetry and prose all have been passed down in the works of later authors. In spite of arguments over the authorship of certain works ascribed to him and the brevity of the fragments, few other classical Greek writers present such a breadth of literary output. Critias, the political figure, author, and philosopher, stands as one of the most controversial and enigmatic figures of fifth-century BC Athens.

Critias’ one significant and original contribution appears to have been a clear distinction between perception through the senses (aisthanomai) and understanding through the mind (gnômê). While there are indications that others (e.g., Empedocles and Heraclitus) may have shared in this differentiation, Critias’ statement is the earliest extant. Apart from this one exception, Critias does not appear to have been an original thinker.

Critias commented that “if you yourself were trained, so that you were sufficient in mind (gnômê), you would thus be least wronged by your own (senses)” (fr. 40). In this statement Critias appears to be in agreement with Protagoras and many other of his contemporaries in the sophistic idea that excellence is teachable. He was furthermore a materialist in his beliefs about the soul and its role in perception. Aristotle and later writers report that Critias believed that the soul (psychê) was the blood, and, in agreement with Empedocles, that the blood around the heart was the seat of perception (noêma) (fr. 23).

Table of Contents

- Life

- Political Career

- Ancient Perspectives on Critias

- Relationship with Socrates

- Drama and Poetry

- Rhetoric

- Writings

- References and Further Reading

1. Life

Critias’ first certain appearance in the historical record is as an alleged participant in the mutilation of the herms in 415 BC. Critias was released on the testimony of Andocides (On the Mysteries 47) in the course of the investigation of the crime, and nothing further is known of his involvement in the matter. There are also sporadic references to Critias’ participation in some of the major events of the last years of the Peloponnesian war. Whether he was a participant in the oligarchic reign of the Four Hundred in 411 BC is uncertain. He posthumously prosecuted Phrynicus, the radical oligarch and ringleader of the Four Hundred (Lycurgus, Against Leocrates 113) after the regime’s collapse in 410 BC.

2. Political Career

In the years that followed, Critias was actively involved in politics as an associate of Alcibiades. Critias proclaims in one of his elegiac poems that he proposed Alcibiades’ return from exile, probably around 408 BC (fragments 4 and 5). With the turn of Athenian popular opinion against Alcibiades, Critias probably followed Alcibiades into exile in 406 BC. During this time Critias became involved in an insurrection in Thessaly, but nothing certain is known of his activities there, apart from Theramenes’ enigmatic statement that Critias was “with Prometheus setting up a democracy and arming the peasants against their masters” (Xenophon, Hellenica 2.3.36). Too little is known of Thessalian history at that time to ascertain whom “Prometheus” was, or to determine the nature of any alleged “democratic” revolution in which Critias may have been involved.

Upon his return from exile in the spring of 404 BC, Critias was one of the “five ephors” who led the various oligarchic factions of post-war Athens (Lysias, Against Eratosthenes 43). Critias was also a leading member of the Thirty, whose brutal reign of terror in 404/403 BC was vividly depicted by Xenophon (Hellenica, Book 2). The reign of terror unleashed by the Thirty saw summary executions, property confiscations, and the exile of thousands of Athenian sycophants, democrats, and metics. Even Theramenes, one of the founding members of the Thirty, was executed without a trial after he dared to openly oppose Critias. Another apparent victim of the Thirty was the still-exiled Alcibiades, who remained in his fortified estates in Thrace. According to the report of Alcibiades’ later biographers-Cornelius Nepos (Alcibiades 10) and Plutarch (Alcibiades 38.5)-it was his old supporter and fellow Socratic companion Critias who gave the assassination order in 403 BC.

There are indications that Critias had some degree of personal control over the Athenian cavalry class and over the Eleven, who acted as executioners (Xenophon, Hellenica 2.4.8). Critias also appears to have been the guiding force behind the more extreme elements of the Thirty as well as their unquestioned leader after the execution of Theramenes in 403 BC. He also appears to have been one of the chief law-givers of the oligarchy (Xenophon, Hellenica 2.3.49).

Whatever plans that Critias and the Thirty had for the establishment of a new oligarchic regime in Athens were abruptly halted by the military successes of a group of pro-democratic exiles led by Thrasybulus at the Athenian border post at Phyle and in the port town of Piraeus. On a single day in May of 403 BC, in a pitched battle between the forces under the command of Thrasybulus and Critias and the supporters of the Thirty, the mastermind of the oligarchic movement fell. At that time, Critias, commander of the phalanx, opted for a deep line of fifty shields for his hoplites. The members of the Thirty themselves stood in the front ranks on the extreme left of the phalanx. Far from shunning the violent danger of the battlefield, Critias positioned himself in the left-most corner of the line. However, the arrangement of the phalanx in a deep column failed, the fighting bloody and costly. Critias was among the more than seventy who fell (Xenophon, Hellenica 2.3.11-13). Critias’ death left the remaining members of the Thirty and the Three Thousand leaderless and in confusion. Attempts at a new oligarchic government failed and the democracy was restored soon afterwards.

A memorial was later erected to Critias and the Thirty depicting a personified Oligarchy carrying torches and setting Democracy on fire. An inscription on the monument’s base, as recorded by a scholiast, read: “This is a memorial of those noble men who restrained the hubris of the accursed Athenian Demos a short time” (scholiast on Aeschines, Against Timarchus 39). The price of this “restraint” was the lives of at least 1,500 Athenians (Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians 35.4).

As Plato admits in his Seventh Letter, the extreme behavior of his second cousin Critias-along with another cousin, Charmides, the leader of the Ten who governed the Piraeus during the rule of the Thirty-effectively ended any thoughts he had previously entertained about a future political career (Plato, Seventh Letter 324d).

3. Ancient Perspectives on Critias

Xenophon characterized Critias as a ruthless, amoral tyrant, whose crimes would eventually be the cause of Socrates’ death. This negative view of Critias was continued by Philostratus, who called him “the most evil… of all men” (Lives of the Sophists 1.16). On the other hand, Plato’s portrayal of his second cousin, Critias, in four dialogues (Lysis, Charmides, Critias, and Timaeus) presents Critias as a refined and well-educated member of one of Athens’ oldest and most distinguished aristocratic families and as a regular participant in Athenian philosophical culture.

Although these portrayals differ, they are not mutually exclusive. Critias’ family was among the most prominent of the old aristocratic Eupatrid clans that had ruled Athens before the advent of the democracy. No fewer than four of his direct ancestors had held the eponymous archonship (the highest office of the Athenian state)–one, a certain Dropides, in 645/644 BC. Solon was among his famous relatives (Plato, Charmides 155a), and both Solon and the poet Anacreon reportedly praised Critias’ ancestors in their poems (Plato, Charmides 157e and Solon, fr. 22 in Iambi et Elegi Graeci. 2nd ed. M.L. West, ed. Oxford 1992).

Although the literary tradition lacks detailed evidence about Critias’ youth, his biographer Philostratus (Lives of the Sophists 1.16) says that Critias’ “formal education was the of the most noble sort,” and Athenaeus (Deipnosophistae 4.84d) notes that his training as a flutist made him famous in his youth. A fragment of a dedication for two victories at the Isthmian games and two victories at the Nemean games in 438 BC by a [Critia]s, son of Callaeschrus, remains (IG I3 1022), but the restoration of the name remains uncertain. It does seem clear that Critias excelled in two of the most important elements of traditional Athenian education: music and athletics.

If Plato accurately reports the characters of historical figures in his dialogues–though surely in fictionalized situations that suited his philosophical ends–then perhaps these dialogues provide glimpses into Critias’ character and behavior. In Plato’s Protagoras, set in 433 BC, Critias appears among the leading sophists–Protagoras, Hippias, Prodicus, and Socrates–and the educated elite of Athens. In the Protagoras, Critias takes part in the dialogue alongside Alcibiades. This pairing is perhaps ironic, since Xenophon records that Athenian anger at the reckless and destructive behavior of Critias and Alcibiades, both associates of Socrates, was the real reason behind the execution of Socrates in 399 BC (Memoirs of Socrates 1.2.12). It is noteworthy that Critias’ only contribution to the philosophical discussion is a plea to the participants to be impartial and fair at a point in which those present increasingly appear either in favor of Socrates or Protagoras. In contrast to Xenophon’s portrayal of Critias as a ruthless tyrant, Plato’s presentation of Critias as a moderating force is a remarkable counterpoint.

Critias’ more substantial role in the Charmides, which opens with the return of Socrates from Potidaea in 432 BC, provides an equally stark contrast to the negative depiction of Xenophon and others. The dialogue centers on the meaning of sophrosyne (self-control), which Charmides–clearly following the lead of his cousin and guardian Critias–defines for Socrates at one point as “minding one’s own business” (Plato, Charmides 161b). Although this particular definition is abandoned in the discussion described in Charmides itself, it reappears in an expanded form as the ultimate meaning of dikaiosyne (justice) in the Republic (433a-b): “that each individual must act in the affairs of the city as each is best fitted by nature to do.” This definition of justice (dikaiosyne) is, of course, held by Plato to be the highest virtue and is central to his utopian conception of the ordering of the various social and political classes of the ideal state.

Critias is also a principal character in both the Timaeus and the Critias, which are set on the day after the events recorded in the Republic in 421 BC. Critias relates the story of Atlantis and its fabled war with Athens some 9,000 years earlier. He had heard this tale from his homonymous grandfather, who, in turn, had heard it from his relative the lawgiver Solon. The story, which Plato has Critias say was preserved by Egyptian priests, presents an idealized portrait of an ancient Athens that matches remarkably well the features of the utopian state described in the Republic. What is significant is that Plato has chosen Critias as the reporter of the Atlantis myth. By doing this Plato invests his second cousin with heightened importance as a man who knew the history of a past age, a time when governments resembled the utopia of the Republic and not the imperfect systems of fourth-century BC Greece.

4. Relationship with Socrates

Among the laws drafted by Critias was an edict forbidding “instruction in the art of words” (Xenophon, Memoribilia 1.2.31). Xenophon reports that Socrates responded with a sarcastic reply: “if someone was a herdsman and made his cattle fewer and more poor, would he not agree that he was a bad herdsman; yet it is a great wonder, if someone was a leader of a city and made his citizens fewer and poorer, that he would not be ashamed nor think himself a bad leader of a city” (Xenophon, Memoribilia 1.2.32). Although it is the relationship between Critias and his former teacher that Xenophon wants to deny, it is Charicles who threatens Socrates with punishment if he does not desist from making statements against the regime (Xenophon, Memoribilia 1.2.37-38). Critias remains in the background of the conversation, making only a withering remark about the philosopher’s affinity for “tanners, craftsmen, and bronze workers” (Xenophon, Memoribilia 1.2.37). In another tête-a-tête, Socrates crudely upbraids a lovestruck Critias for his apparently overzealous attraction to a handsome youth named Euthydemus by saying that he was rubbing against the young man “like a little pig scratching itself against a rock” (Xenophon, Memoribilia 1.2.29-30). These vignettes of Socrates and Critias are both amusing and make a point: Critias and Socrates knew each other, but also were often at odds with one another.

Despite the threats and obvious tension between the two, Socrates survived the terror and the subsequent civil war. Perhaps it was at Critias’ insistence that Socrates’ insubordinate behavior was overlooked during the terror. Whatever the reason, it is clear from the events of Socrates’ trial in 399 BC and the scattered rebukes in fourth- and third-century BC literature that the attachment between Critias and the philosopher held fast in the popular mind (e.g., Xenophon, Memoribilia 1.2.12; Aeschines, Against Timarchus 173; and comic fragment 3:122 in T. Kock, ed. Comicorum Atticorum Fragmenta. Teubner 1880-1888).

a. Philosophical Views

Although the tragic events of the last year of Critias’ life have left a vivid picture of a radical and brutal politician, it is important to remember that Critias was also a regular and leading participant in Athenian philosophical culture. As a scholiast on Plato’s Timaeus (20a) notes: “he was called an amateur among philosophers, and a philosopher among amateurs.” Here the term “amateur” clearly refers to Critias’ aristocratic background in the sense that aristocrats by nature are “amateurs”–or perhaps more accurately “those who do not take money for their work.”

While little remains of Critias’ philosophical writing, numerous quotations by later writers attest to multiple works on a variety of topics. Unfortunately, these fragments reflect neither a comprehensive nor a thorough understanding of his philosophy. Enough remains, however, to understand something of his practice as a philosopher, his epistemology, his conception of the soul, and his ethics.

Much of his philosophical teaching appears to have been presented in multiple books of Homilies and Aphorisms. It is tempting to imagine that the Homilies (which may be understood either as “lectures” or “conversations”) may have represented an early form of the dialogue, but an insufficient number of fragments survive to give a clear picture of their literary character. If Critias’ Homilies were indeed in dialogues, he may have influenced his cousin Plato in his choice of an innovative literary form for the presentation of philosophy.

b. Distinction Between Sense and Understanding

Critias’ one significant and original contribution appears to have been a clear distinction between perception through the senses (aisthanomai) and understanding through the mind (gnômê). While there are indications that others (e.g., Empedocles and Heraclitus) may have shared in this differentiation, Critias’ statement is the earliest extant. Apart from this one exception, Critias does not appear to have been an original thinker.

Critias commented that “if you yourself were trained, so that you were sufficient in mind (gnômê), you would thus be least wronged by your own (senses)” (fr. 40). In this statement Critias appears to be in agreement with Protagoras and many other of his contemporaries in the sophistic idea that excellence is teachable. He was furthermore a materialist in his beliefs about the soul and its role in perception. Aristotle and later writers report that Critias believed that the soul (psychê) was the blood, and, in agreement with Empedocles, that the blood around the heart was the seat of perception (noêma) (fr. 23).

A fragment of Critias’ tragedy Perithus illustrates more clearly the point of these fragments: “A noble character (chrêstos tropos) is more credible than law, for no orator can overcome it…” (fr. 22) As M. Untersteiner has argued, Critias believed that “the concrete manifestation of gnômê is realized in tropos, ‘character,’ where the idea of will and decision is included in the very root of the term.” An example of Critias putting his philosophical beliefs into practice may be found in the showdown with his political rival Theramenes before the other members of the Thirty and the Athenian councilors. At the very moment that Theramenes seems to be swaying the audience, Critias steps forward and says: “I believe the business of a leader should be that if he sees his comrades being deceived, he should not permit it.” Then, backed up by an armed bodyguard, Critias summarily sentences Theramenes to death and has him dragged from the altar in the council chamber (Xenophon, Hellenica 2.3.51).

c. Views on Law and Morals

Critias believed that law, order, and the divine are merely human creations that function as tyrants over humanity–thus, morality is relative to the individual and a trained, noble character should be regarded as superior to any law. This ethical preference for the educated individual over human law occurs in several of the other fragments of his work, but is best illustrated in the fragment from the satyr play Sisyphus, which is attributed to Critias. Authorship of the play continues to be disputed by scholars, but there is nothing in the one surviving fragment (fr. 25) that cannot be paralleled either in the other fragments or in what is known of Critias’ beliefs. In the play Critias describes the invention both of law and the gods by a clever and wise man (puknos kai sophos anêr) who wished to deceive and control the rest of humanity through fear of supernatural powers. If law and the gods are a human construct, it follows that they are no match for the learned individual. Although the quotation is clearly meant to be spoken by Sisyphus, who was condemned by the gods for his impious acts, the second-century AD medical doctor and skeptic Sextus Empiricus quotes this passage as evidence of Critias’ atheism.

Additional circumstantial evidence for Critias’ atheism may be found in his open blasphemy toward the gods at the climax of the condemnation of his political rival Theramenes (Xen. Hell. 2.3.52-55). Having taken refuge atop the sacred altar in the council house, Theramenes calls Critias and his followers “the most unholy of men.” At Critias’ behest, the herald orders the Eleven to drag Theramenes from the altar, and he is carried off to his execution “beseeching the gods to witness these events.”

5. Drama and Poetry

Apart from the surviving fragments of the plays and the elegiac and hexameter poetry attributed to him, nothing is known about Critias’ work as a playwright and poet. Only a single quote from the Tennes survives, the end of a hypothesis of the Rhadamanthys remains along with three brief fragments, and some nine fragments are extant from his Pirithous. A substantial fragment from the satyr play, Sisyphus, (discussed above) also remains.

In the sole surviving fragment of his hexameters, Critias celebrates the sixth-century BC poet Anacreon, who was reputed to be the lover of Critias’ homonymous grandfather (fr.1). This fragment also contains the earliest reference to the kottabos game, a favorite sport at aristocratic symposia; another fragment in elegaic couplets further records the Sicilian origins of the game (fr. 2). Critias’ apparent love for this drinking game, which included a brief prayer for one’s younger lover, is undoubtedly behind Theramenes’ famous last words at his execution in 403 BC. After having been compelled to drink hemlock, Theramenes reputedly tossed the dregs from his cup and in clear imitation of kottabos practice said: “This to Critias the fair” (Xenophon, Hellenica 2.3.56).

Two fragments of Critias’ elegies honor Alcibiades (fragments 4 and 5). One of the fragments, in fact, states emphatically that it was Critias who proposed the successful motion for Alcibiades’ return from exile (fr. 5).

Another brief pentameter line records the axiom: “More men are good from practice, than from nature” (fr. 9). The axiom fits well what is known of Critias’ emphasis on training in the building of character, but is perhaps striking when his own aristocratic pedigree is considered.

The remaining elegaic couplets, which record various customs and facts relating to the Spartans, apparently belonged to a “Politeia of the Lacedaemonians” in verse (fragments 5-7). Politeia is a term often best translated as “constitution,” but often refers more broadly to a “way of life” rather than strictly political matters. Critias appears to have been one of the first to compose such “constitutions” either in verse or prose. Critias reportedly believed that the Spartan politeia was the best (Xenophon, Hellenica 2.3.34), and so it is no accident that the majority of the fragments come from his constitutions of the Lacedaimonians (one in prose, the other in verse).

6. Rhetoric

In his rhetorical training, Critias was influenced by the grand, antithetical style of Gorgias and Antiphon and continued to be read by students of rhetoric such as Cicero (On Oratory 2.23.93) throughout antiquity. Furthermore, his work was remembered by later rhetoricians of the Second Sophistic as an excellent example of pure Attic oratory (see, for example, Philostratus, Lives of the Sophists 9.16 and 16.1.34-40). None of Critias’ speeches survive intact, although H.T. Wade-Gery has argued that a speech attributed to Herodes Atticus is a work of Critias. However, U. Albini’s careful and thorough study of the speech leaves no possibility for a date of composition of the “Herodes” speech earlier than the second century AD. More profitably, S. Usher has argued that the speeches given by Critias in Xenophon’s Hellenica are condensed versions of the originals. Xenophon almost certainly knew Critias and his rhetorical style personally, and may have been present to hear him attack Theramenes in the council chamber, but how precisely he recalled the words spoken must remain a matter of speculation.

7. Writings

Fragments of Constitutions of Thessaly (fr. 31) and Lacedaemon (frr. 32-37) written by Critias in prose are extant; A. Boeckh and other scholars have attributed to Critias a “Constitution of the Athenians” wrongly ascribed to Xenophon, but this argument has found little favor. Other extant fragments from unnamed prose works include biographical details of the lives of the poet Archilochus (fr. 44) and the Athenian statesmen Themistocles (fr. 45) and Cimon (fr. 52). In addition, the lexicographer Pollux cites words from Critias’ works on some twenty occasions–a testimony to Critias’ stature as a writer of pure Attic Greek and, perhaps, to his educated diction.

In the fragments from his “Constitution of the Lacedaimonians” Critias never fails to record his admiration for even the most mundane features of Spartan society. Along with Lacedaimonian moderation in drinking wine and toasting their fellows (fr. 6), Critias stated that the Laconian way of raising children (fr. 32), the shape of Laconian drinking cups, Laconian shoes, Laconian cloaks, and even Laconian furniture (fr. 34) were the best. He also recorded that “it was a Lacedaimonian, Chilon the wise, who once said, ‘Nothing too much, all beautiful things arrive at the proper moment'” (fr. 7).

Critias was one of the first to write histories of individual city states. It is likely that Xenophon used and perhaps even imitated Critias in the writing of his own “Constitution of the Lacedaemonians,” although he never says as much. It is also possible, if not certain, that Aristotle used Critias’ work in the composition of his “constitutions” of the Greek city-states, but this too must remain an open question.

The breadth of Critias’ work in philosophy, drama, poetry, historical writing, rhetoric, and politics is impressive. He was not a particularly original thinker, but generalists seldom are. His leadership of the Thirty–one of Athens’ darkest, bloodiest moments–has tended to overshadow his literary and philosophical work, but Critias was no ordinary despotic thug. A scion of one of Athens most noble families, highly-educated, cultured, a writer of poetry and prose, a powerful speaker, and brave, Critias was perhaps the greatest tragedy the city ever produced.

8. References and Further Reading

- H. Diels and W. Kranz, eds. Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker. 10th ed. Berlin 1960-1961. Fragments of Critias’ works are cited above according to the numeration of Diels-Kranz.

- U. Albini, [Erode Attico] peri politeias. introduzione, testo critico e commento. Florence 1968.

- J.K. Davies, Athenian Propertied Families 600-300 B.C. Oxford 1971.

- H.T. Wade-Gery, “Kritias and Herodes,” in Essays in Greek History. Oxford 1958 271-292.

- W. Morison, The “Amateur” as Tyrant: A Socioeconomic Study of Kritias. Unpublished Masters Thesis: California State University, Fresno 1990

- D. Stephans, Critias: Life and Literary Remains. Cincinnati 1939.

- M. Untersteiner, The Sophists. New York 1954.

- S. Usher, “Xenophon, Critias, and Theramenes,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 88 (1968) 128-135.

Author Information

William Morison

Email: morisonw@gvsu.edu

Grand Valley State University

U. S. A.