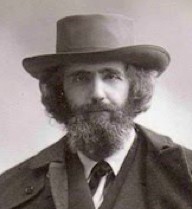

Franz Brentano (1838-1917)

Franz Brentano was a major philosopher of the second half of the 19th century who had a strong impact on the development of early phenomenology and analytic philosophy of mind. Brentano’s influence on students such as Karl Stumpf and Edmund Husserl was extensive, but Sigmund Freud was also much inspired by Brentano’s teaching and personality. Along with Bernard Bolzano, Brentano is acknowledged today as the co-founder of the Austrian tradition of philosophy.

Franz Brentano was a major philosopher of the second half of the 19th century who had a strong impact on the development of early phenomenology and analytic philosophy of mind. Brentano’s influence on students such as Karl Stumpf and Edmund Husserl was extensive, but Sigmund Freud was also much inspired by Brentano’s teaching and personality. Along with Bernard Bolzano, Brentano is acknowledged today as the co-founder of the Austrian tradition of philosophy.

Two of his theses have been the focus of important debates in 20th century philosophy: the thesis of the intentional nature of mental phenomena, and the thesis that all mental phenomena have a self-directed structure which makes them objects of inner perception. The first thesis has been taken up by proponents of the representational theory of mind, while the second thesis continues to inspire philosophers who advocate a self-representational theory of consciousness.

Brentano’s interests, however, were not limited to the philosophy of mind. His ambition was greater: to make the study of mental phenomena the basis for renewing philosophy altogether. This renewal would encompass all philosophical disciplines, but especially logic, ethics, and aesthetics. Moreover, Brentano was a committed metaphysician, much in contrast to Kant’s transcendental idealism and its further developments in German philosophy. Brentano advocated a scientific method to rival Kantianism that combined Aristotelian ideas with Cartesian rationalism and English empiricism. He was a firm believer in philosophical progress backed up by a theistic worldview.

Table of Contents

- Biography

- Philosophy of Mind

- The Triad of Truth, Goodness and Beauty

- Epistemology and Metaphysics

- History of Philosophy and Metaphilosophy

- References and Further Reading

1. Biography

Franz Brentano was born into a distinguished German family of Italian descent whose influence on Germany’s cultural and academic life was considerable. His uncle Clemens Brentano (1748-1842) and his aunt Bettina von Arnim (1785-1859) were major figures of German Romanticism, and his brother Lujo Brentano (1844-1931) became an eminent German economist and social reformer. The Brentano brothers considered their family as “zealously Catholic” (Franz Brentano) and “highly conservative” (Lujo Brentano). Brentano’s early association with the Catholic Church complicated his life and affected his academic career in Würzburg and Vienna.

a. Life

Brentano was born on January 16, 1838, in Marienberg on the Rhine. He was one of five children who reached adulthood. He studied philosophy and theology in Munich, Würzburg, Berlin, and Münster. Among his teachers were the philologist Ernst von Lasaulx (1805-1861), the Aristotle scholar Friedrich Trendelenburg (1802-1872), and the Catholic philosopher Franz Jacob Clemens (1815-1862). Under Clemens’s supervision, Brentano first began a dissertation on Francisco Suárez, but then took his doctorate at Tübingen in 1862 with a thesis on the concept of being in Aristotle. He then enrolled in theology and was ordained a priest in 1864. After his habilitation in philosophy in 1866 in Würzburg, Brentano began his teaching career there, first as a Privatdozent, and from 1872 as an Extraordinarius. Among his students in Würzburg were Anton Marty and Carl Stumpf. The fact that he left the University of Würzburg shortly thereafter was due to a falling out with the Catholic Church. In the fight between liberal and conservative groups, which took place both inside and outside the Catholic Church at the time, Brentano wrote in a letter to a Benedictine abbot that he felt himself “caught between a rock and a hard place” (quoted in Binder 2019, p. 79). A key role was played by a document he had written for the bishop of Mainz where he was critical of the dogma of the infallibility of the Pope proclaimed by the first Vatican Council in 1870.

Despite this rift, Brentano was able to continue his academic career. After he convinced the responsible authorities in Vienna that he was neither anti-clerical nor atheistic, he was appointed to a professorship of philosophy at the University of Vienna in 1874, supported among others by Hermann Lotze (1817-1881). As in Würzburg, Brentano quickly found popularity among the students in Vienna. These included Edmund Husserl, Alexius Meinong, Alois Höfler, Kasimir Twardowski, Thomas Masaryk, Christian Ehrenfels and Sigmund Freud. Privately, Brentano found connections to the society of the Viennese bourgeoisie. He met Ida von Lieben, daughter of a wealthy Jewish family, finally left the Catholic Church, and married her in Leipzig in 1880. This union was followed by a protracted legal dispute in which Brentano tried in vain to regain his professorship, which he had to give up as a married former priest in Austria. In 1894, after the unexpected death of his wife Ida, Brentano was left alone with their six-year-old son Johannes (also called “Giovanni” or “Gio”). One year later, he decided to end his teaching career, now as a Privatdozent, and left Austria first for Switzerland, then for Italy.

Although Brentano was offered several professorships in both countries, the 57-year-old decided to live as a private scholar from then on. In 1896, he acquired Italian citizenship and lived in Florence and Palermo. He continued to spend summers in Austria at his vacation home in Schönbühel on the Danube. In 1897 Brentano married his second wife, the Austrian Emilie Rüprecht. She not only took care of the household and his son, but also increasingly supported Brentano in his scientific work, since his vision had started to decrease around 1903. Due to the outbreak of World War I and the entry of Italy into the war, Brentano moved with his family to Zurich in 1915. During his time as a private scholar, he not only kept in touch with a small circle of students who had meanwhile made careers in Germany and Austria, but he was also in lively exchange with philosophers and intellectuals in Europe. Inspired by these contacts, Brentano was highly active intellectually until his death on March 17, 1917.

b. Works

Brentano’s philosophical work consists of his published writings and an extensive Nachlass, which includes a large amount of lecture notes, manuscripts, and dictates from his later years. The bequest also contains a wealth of correspondence that Brentano exchanged with his former students (notably Anton Marty) and students of his students (notably Oskar Kraus). Other correspondents of Brentano were eminent scientists and philosophers such as Ludwig Boltzmann, Gustav Theodor Fechner, Ernst Mach, John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer.

As Brentano was a prolific writer, but reluctant to prepare his works for publication, it was mostly left to his students and later generations of editors to prepare publications from his Nachlass manuscripts. In doing so, the editors often took the liberty of adapting and modifying Brentano’s original text, often without marking the changes as such. As a result, only the works published by Brentano himself are a truly reliable source, while the volumes edited after Brentano’s death vary widely in editorial quality (see the warnings in References and Further Readings, section 3).

2. Philosophy of Mind

Brentano believed that psychology should follow the example of physiology and become a full-fledged science, while continuing to play a special role within philosophy. To meet this goal, he conceived of psychology as a standalone discipline with its own subject matter, namely mental phenomena. The basic principles that inform us about these phenomena are emblematic of his conception of the mind and will be discussed in more detail below: his thesis of the intentional nature of mental phenomena; his thesis of inner perception as a secondary consciousness; and his classification of mental acts into presentations, judgements, and phenomena of love and hate.

In later years, Brentano drew an important distinction between descriptive and explanatory (“genetic”) psychology. These sub-disciplines of psychology differ both in their task and the methods they need to accomplish that task. According to Brentano, an analytical method is needed to describe psychological phenomena. We must analyze the experiences, which often only appear indistinct to us in inner perception, in order to precisely determine their characteristics. Genetic psychology, on the other hand, requires methods of explanation; it must be able to explain how the experiences that we perceive come about.

Brentano prepares the ground for that distinction in his seminal work Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint, first published in 1874, and fleshes it out fully in the second edition of the Classification of Mental Phenomena in 1911. The second edition contains several new appendices, but it is still far from completing the book project as Brentano originally conceived it. According to this plan Brentano wanted to add four more books that give a full treatment of the three main classes of mental phenomena (presentations, judgements, acts of the will and emotional phenomena), as well as a treatment of the mind-body problem, which shows that some notion of immortality is compatible with our scientific knowledge of the mind (see section 4d).

While the Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint secured Brentano’s place in the history of philosophy of mind, it is not an isolated piece in Brentano’s oeuvre. It stands somewhat in the middle between his earlier work on The Psychology of Aristotle (1867) and his lectures on Descriptive Psychology (1884-1889). If we add to this Brentano’s lectures on psychology in Würzburg (1871-1873) and the works on sensory psychology in his later years (1892-1907), we see a continuous preoccupation with questions of psychology over more than 40 years.

a. Philosophy and Psychology

Brentano’s interest in the philosophy of mind was driven by the question of how psychology can claim for itself the status of a proper science. Taking his inspiration from Aristotle’s De Anima, Brentano holds that progress in psychology depends on progress in philosophy, but he takes this dependence to go both ways. This means that we can ascribe to Brentano two programmatic ideas:

- Philosophy helps psychology to clarify its empirical basis as well as to determine its object of research

- Conversely, psychology contributes in various ways to many areas of philosophy, especially epistemology, logic, ethics, aesthetics, and metaphysics

Implementing the first idea involved Brentano in addressing thorny questions of methodology and classification: What is the proper method for studying mental phenomena? How do mental phenomena differ from non-mental phenomena? Is consciousness a characteristic of the mental? How does consciousness of outer objects differ from what Brentano calls “inner consciousness”? How can we classify mental phenomena? The first two books of the Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint provide ample answers to these questions.

During his years in Vienna (1874-1895), Brentano’s interest shifted more and more towards his second programmatic idea. In this context, Brentano found it necessary to distinguish more sharply between a “descriptive” and a “genetic” psychology. With this distinction in hand, he tried to show what psychology might contribute to various parts of philosophy. While philosophy may be autonomous from genetic psychology, it builds on the resources of descriptive psychology. How this shift towards descriptive psychology gradually took hold of Brentano’s thinking can be seen from the titles of his Vienna lectures: “Psychology” (1874-1880), “Selected questions of psychology and aesthetics” (1883-86), “Descriptive psychology” and “Psychognosy” (1887-1891).

It was only in later years that Brentano returned to questions of genetic psychology. Texts from the last decade of his life were published posthumously in a volume entitled On Sensory and Noetic Consciousness. Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint III (1928, English translation 1981). The subtitle is misleading because this volume is not a continuation of Brentano’s earlier book. How Brentano planned to continue his Psychology has been succinctly described in Rollinger (2012).

b. Inner Perception

In studying mental phenomena, philosophers often emphasize a crucial distinction between two questions:

-

- How can we obtain knowledge of our own mental acts?

- How can we obtain knowledge of mental acts in other subjects?

In dealing with these questions, Brentano rejects the idea that separating the two questions means to postulate an “inner” sense in addition to the outer senses. This old empiricist idea inherited from Locke was still popular among philosophers and psychologists of Brentano’s time. As an alternative to this old view, Brentano suggests that we access our own mental phenomena by simply having them, without the need of any extra activity such as introspection or reflection.

To appreciate the large step that Brentano takes here, one must address several much-contested questions about the nature of our self-knowledge (see Soldati 2017). To begin with, how does Brentano distinguish between “inner perception” and what he calls “inner observation”? One way to do so is to consider the role that attention and memory play in accessing our own mental states. Like John Stuart Mill, Brentano argues that attending to one’s current experiences involves the possibility of changing those very experiences. Brentano therefore suggests that inner perception involves no act of attention at all, while inner observation requires attending to past experiences as we remember them (see Brentano 1973, p. 35).

But Brentano goes further than that. According to him, we must not think of inner perception as a separate mental act that accompanies a current experience. Instead, we should think of an experience as a complex mental phenomenon that includes a self-directed perception as a necessary part. Some scholars have taken this view to imply that inner perception is an infallible source of knowledge for Brentano. But this conclusion needs to be drawn with care. Take, for instance, a sailor who mistakenly thinks he sees a piece of land on the horizon. Inner perception is telling him with self-evidence that he is having a visual experience of a piece of land. And yet he is mistaken about what he sees, if he mistakes a cloud, let’s say, for a piece of land. Still, Brentano would say that it was not inner perception that misled the sailor, but rather his interpretation of the visual content as of a piece of land. Such misinterpretations are errors of judgements, or attentional deficits that happen in observing or attending to the content of our experience. In the end, Brentano seems committed to the view that unlike observation, inner perception has no proper content and therefore has nothing it could be wrong about.

How can Brentano defend this commitment? One way to do so would be to appeal to the authority of Aristotle and his view that we are seeing objects, while at the same time experiencing seeing them. While Brentano is always happy to follow Aristotle, he also bolsters his view with new arguments. In the present case he does so by drawing on the ontology of parts and wholes. A common understanding of parts and wholes has it that a whole is constituted by detachable parts, like a heap of corn is constituted by single corns as detachable parts. But this model does not apply to inner perception, says Brentano. A conscious experience is not constituted like a heap of corn: you can’t detach the person who sees something from the subject who innerly perceives the seeing. This leads Brentano to the key insight that what appears to us in inner perception is nothing other than the entire mental act that presents itself to us.

How then does Brentano explain the immediate knowledge we have of our own mental phenomena? Having removed any appeal to a faculty of inner sense, Brentano ends up with a form of conceptual insight that could be summarized in the following way: Immediate knowledge of our present mental states comes with the insight that we can only conceptually separate what we see, feel, or think from the act of seeing, feeling or thinking. Such immediate knowledge becomes impossible when we consider the life of other people. In this case we are restricted to a form of “indirect knowledge” of their feelings and thoughts by listening to what they say or observing their behavior. This indirectness implies that we may only be certain that the other person feels or thinks something, without knowing what exactly it is that they feel or think. Here we are not just dealing with conceptual differences, but with a real difference between our own experiences and the mental phenomena we discover in the minds of others.

But are we able to “read” the minds of other people? In book II of his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint, Brentano argues that psychology could not acquire the status of a proper science merely on the basis of the data of inner perception. We need to make sure that our conception of the mind is not biased by our own experiences. The data that help us to guard against such an egocentric bias include (a) biological facts and the behavior of others indicating, for example, that they feel hunger or thirst like we do, (b) the mutual understanding of communicative acts such as gestures or linguistic behavior, as well as (c) the recognition of behavior as voluntary actions performed with certain intentions.

In drawing on these resources, Brentano shows no skepticism towards our social instincts. It is part of our daily practice to infer from the behavior of others whether someone is hungry, whether he is ashamed because he has done something wrong, and so on. For Brentano, there is no reason why a scientific psychology should dispense with such inferences. On the contrary, he acknowledges that a psychology that limits itself exclusively to the knowledge of its own mental phenomena is exposed to the danger of far-reaching self-deceptions. Psychology must face the task of tracking down such deceptions.

Brentano thus provides a thoroughly optimistic picture of the empirical basis of psychology. With inner perception, it can count on the immediate and potentially error-free access that we have to our own experiences, while the fallacies that arise in self-observation can be rectified by relying on a rich repertoire of inferences about other people’s mental states.

c. Intentionality

Psychology is a self-standing science, says Brentano, because it has a specific subject matter, namely mental phenomena. In his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874), Brentano argues that these phenomena form a single and unified class thanks to a general characteristic that distinguishes them from all other phenomena: their intentional directedness to objects.

This so-called “intentionality thesis” has sparked a wide-ranging debate among Brentano’s pupils. Husserl and Twardowski–just to mention two–came up with different readings of what Brentano describes as the “intentional directedness towards an object.” Their disagreement paved the way for an interpretation (due to Oskar Kraus and later taken up by Roderick Chisholm) that ascribes to Brentano a fundamental change of view about the nature of intentionality. According to this interpretation, we find in the early Brentano a rich ontology of intentional objects that is threatened by inconsistency. Therefore, Brentano later developed a radical critique of non-real objects that forced him to accept a non-relational theory of intentionality. In the meantime, this interpretation has been disputed for various reasons: Some scholars (for example, Barry Smith, Arkadiusz Chrudzimski) tried to resolve the alleged inconsistencies in Brentano’s early ontology, thus removing the need for a radical shift to a non-relational theory of intentionality, while other scholars (e.g. Mauro Antonelli and Werner Sauer) tried to show that Brentano’s later view is not very different from his earlier conception. Still others have discussed whether one finds at the core of Brentano’s theory a relational concept of intentionality that applies to some but not all mental phenomena, thus putting pressure on the thesis that all mental phenomena share the same feature of intentionality (see Brandl, 2023).

These different descriptions of intentionality played an important role in the reception of the concept by Brentano’s students. Following Twardowski, Husserl insisted on the distinction between the content and the object of an intentional act, stressing (against Twardowski) that some acts are intentional and are yet objectless, e.g. my presentation of a golden mountain. Following this line, Husserl developed a non-relational, semantic view of intentionality in his Logical Investigations (1900/1901), according to which intentional acts are acts of “etwas meinen” (meaning something). Going beyond Brentano and Twardowski, Husserl argues that acts of meaning instantiate ideal species that account for the objectivity of meaning. Although Brentano seemed to be aware of the semantic problem of the objectivity of meaning in some of his lectures, this was clearly not a central concern for his understanding of intentionality. Meinong, on the other hand, extends Brentano’s concept of intentionality in the opposite direction to Husserl’s: not only is there no sharp distinction between semantics and ontology in Meinong, but all mental acts, including my presentation of a golden mountain, in his view have an object, which may or may not exist, or may simply belong to the extra-ontological realm (Außersein). In any case, Meinong defends a fully relational view of intentionality.

Given the plurality of developments of the concept within his school and the plurality of descriptions offered by Brentano himself, one lesson to be drawn from this debate is that the scholastic terminology used by Brentano is much less informative than it has been taken to be. Brentano seems to use different terms for object-directedness in the same way that one uses different numerical terms to measure the temperature of a body in Celsius or Fahrenheit. In putting mental phenomena on different scales, metaphorically speaking, he highlights some of their differences and commonalities and describes these as “having the same intentional content” or “being directed at the same object.” Take sense perception, for example. If every mental phenomenon has an object, then both my seeing and my imagining an elephant have an object. While this is true according to one use of the term “object,” it is not true if we want to compare an act of perception with an act of hallucination. Then, the so-called “object” of the sensory experience might be better described as a “content” of experience. It fills the grammatical gap in the expression “I see X,” which the hallucinator might also use.

Another controversy concerns phenomena that do not appear to be intentional at all. For instance, one can simply be in a sad mood without being sad about a particular event. Or one may generally tend to jealousy, without that jealousy being triggered by any particular object. Brentano’s intentionality thesis has been defended on the grounds that all mental states fulfill a representational function. The function of being sad could be, for example, to cast any goal we are striving for in a negative light. This could explain the paralyzing effect of sadness. But there is also the possibility of allowing that some mental phenomena may have objects only in a derived sense: for instance, when a subject perceives herself as being in a certain mood. The mood or character trait in itself might be “undirected,” but it would still be an object of inner consciousness when the subject perceives herself as being sad.

Brentano was not yet concerned with the many further questions raised by a representational theory of the mind. Thus, it is not clear how he would treat activities, processes, and operations that underlie our sensory experiences, feelings or acts of the will. Would they have intentional content for him only if they are part of our consciousness? Or would Brentano regard them as non-intentional “physical” phenomena to be studied by the physiological sciences? Perhaps the best way to relate Brentano to the contemporary debate about such questions is to say that he promotes a kind of qualitative psychology that does not need to invoke unconscious mental processes (see Citlak, 2023).

d. Descriptive Psychology

In the manuscripts starting from 1875, in which Brentano worked on the continuation of his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint, one finds the first explicit mention of a separation between descriptive and genetic psychology. The basic idea behind this distinction is that a science of psychology cannot get off the ground unless it is able to identify the components of consciousness and their interrelationships. This requires something like a “geography” of mental concepts, which descriptive psychology is supposed to provide.

Although Brentano approaches this issue in the spirit of the empiricism of Locke and Hume, his objectives are somewhat closer to Descartes’, that is, to find the source of conceptual truths that are self-evident. Combining empiricism about concepts with the search for self-evident conceptual truths is the key to understanding the aim of descriptive psychology, which can be summarized as follows: Descriptive psychology aims to determine the elements of consciousness on the basis of inner perception, and thus to show how we arrive at concepts and judgements that we accept as self-evident and absolutely true. How Brentano tries to implement this plan can be seen in some examples that he discusses in his lecture courses. In one example, he asks whether it is possible to make contradictory judgements. Brentano denies that this is possible as soon as we have a clear perception of the fact that the judgements “A exists” and “A does not exist” cannot both be true. In another example, he asks whether one can feel a sensation without attributing content to that experience. Again, Brentano argues that this is impossible, and that we know this once we have a clear grasp of what “feeling a sensation” means. And we get a clear grasp of what “feeling a sensation” means by describing or analyzing the experience of feeling a sensation into its more basic constituents, by providing examples of such cases, by contrasting different cases, and so on. Doubts about the validity of these results are possible, but they can be treated as temporary. They can only arise while our knowledge of the elements of consciousness and their connections is incomplete.

In summary, we can say that Brentano conceived of descriptive psychology as an epistemological tool. It is aimed at principles which, like the axioms of mathematics, are immediately self-evident or can be traced back–in principle–to immediately self-evident truths. The caveat “in principle” reminds us that we may have good reason to believe that these self-evident truths exist even if we do not yet know what they are.

3. The Triad of Truth, Goodness and Beauty

In the second half of the 19th century the question of the objective character of logic, ethics and aesthetics became a much-contested issue in philosophy. Brentano’s answer to this question is guided by a grand idea: In these disciplines, the theoretical principles of psychology find their application. The domain of application is fixed in each case by one of the three fundamental classes of mental phenomena: logic is the art of making correct judgements, notably judgements inferred from other judgements; ethics deals with attitudes of interest, such as emotional and volitional acts, which direct us to what is good; while aesthetics examines presentations and our pleasure in having them, which makes us acquainted with what is beautiful.

Brentano thus places psychology at the base of what appears to be a philosophical system. The idea of such a system, however, was severely criticized by Husserl, who accused Brentano of psychologism. From the point of view of logic, this accusation weighs heavily since Brentano transforms the laws of logic into laws of correct thinking. But the objection here is a general one. It can also be used to deny that ethics should be based on moral psychology, and that aesthetics should be based on the psychology of imagination. If Brentano has a good answer to Husserl, it must be a general one.

a. A Philosophical System

Brentano was never convinced by Husserl’s claim that phenomenology can only play a foundational role within philosophy if it is freed from its psychological roots. His answer to Husserl’s reproach was a counter-reproach: Whoever speaks of “psychologism” really means subjectivism, which says that knowledge claims may only be valid for a single subject. For instance, an argument may be valid for me, even if others do not share my view. Pointing to his notion of self-evidence, which is not a subjective feeling at all, Brentano sees his position as shielded from this danger. He regards Husserl’s accusation as based on confusion or deliberate misunderstanding.

The jury is still out on this. While most phenomenologists tend to agree with Husserl, others see nothing wrong with the kind of psychologism that Brentano advocates. Some go even further and insist that only by reviving Brentano’s project of grounding mental concepts in experience can we hope to avoid the dead ends in the study of consciousness to which materialism and functionalism lead (see Tim Crane, 2021).

An interpretation of Brentano that also tries to make progress on the issue of psychologism has been proposed by Uriah Kriegel:

In order to understand the true, the good and the beautiful, we must get a clear idea of (i) the distinctive mental acts that aim at them, and (ii) the success of this aim. According to Brentano, the true is that which is right or fitting or appropriate to believe; the good is that which is right/appropriate to love or like or approve of; and the beautiful is that which is right/appropriate to be pleased with (U. Kriegel: The Routledge Handbook of Franz Brentano and the Brentano School. p. 21).

Kriegel’s interpretation is inspired by a tradition, going back to Moses Mendelssohn, of conceiving of truth, goodness, and beauty as closely related concepts. Brentano gives this idea a psychological twist:

It is necessary, then, to interpret this triad of the Beautiful, the True, and the Good, in a somewhat different fashion. In so doing, it will emerge that they are related to three aspects of our mental life: not, however, to knowledge, feeling and will, but to the triad that we have distinguished in the three basic classes of mental phenomena (Brentano 1995, 261).

Brentano scholars must decide how much weight to give to the idea expressed in this quotation. While Kriegel believes that the idea deserves full development, others are more sceptical. They point out that such a system-oriented interpretation goes against the spirit of Brentano’s philosophising. Wolfgang Huemer takes this line when he suggests that “Brentano’s hostility to German system philosophy and his empiricist and positivist approach made him immune to the temptation to construct a system of his own” (Huemer 2021, p.11).

Another question that arises at this point is how to integrate metaphysics into the system proposed by Kriegel. Brentano hints at a possible answer to this question by adding to the triad “the ideal of ideals,” which consists of “the unity of all truth, goodness and beauty” (Brentano 1995, 262). Ideals are achieved by the correct use of some mental faculties. Whether this also holds for the “ideal of ideals” is unclear. Perhaps Brentano is referring here to a form of wisdom that emerges from our ability to perceive, analyse and describe the facts of our mental life (see Susan Gabriel, 2013).

b. Judgement and Truth

Brentano adopts a psychological approach to logic which stands opposed to the anti-psychologistic consensus in modern logic that takes propositions, sentences, or assertions as the primary bearers of truth. Brentano’s approach starts from the observation that simple judgements can easily be divided into positive and negative ones. For Brentano, a simple judgement is correct if it makes the right choice between two responses. We can either acknowledge a presented object when we judge that it exists, or reject it when we judge that it does not exist. To illustrate this, suppose you have an auditory experience where you are presented suddenly with a gunshot. The sound wakes you up and you have no clue as to whether what you heard was real or just a dream. You are presented with content (the gunshot heard), and now you take a stance on this content, either by accepting it (“yes, it’s a gunshot”) or rejecting it (“no, it’s not a gunshot”). The stance you take will be right or wrong, and the resulting judgement will be true or false.

Now, there are two different ideas here that need to be carefully distinguished. One is the following concept acquisition principle:

We acquire the concept of truth by abstracting it from experiences of correct judgement.

The other is a definition of truth:

A judgement is true if and only if it is correct to acknowledge its object or if it is correct to reject its object.

The idea of defining truth in this way raises the question of how it relates to the classical correspondence theory of truth. The critical issue here is the concept of “object,” and the ontological commitments connected with this term. The common view is that Brentano rejected the view that facts or states of affairs could be objects standing in a correspondence relation to a judgement. In a lecture given in 1889, entitled “On the Concept of Truth,” Brentano rehearses some of the criticisms that the correspondence theory has received. He draws particular attention to the problem of negative existential judgements such as “there are no dragons.” This judgement seems to be true precisely because nothing in reality corresponds to the term “dragon.” For Brentano, this speaks not only against the introduction of negative facts, such as the fact that there are no dragons, but also against the acceptance in one’s ontology of states of affairs that might obtain if there were dragons, for example the state of affairs that dragons can sing.

But abandoning the correspondence theory has its price. How can Brentano distinguish between truth on the one hand, and the more demanding notion of correctness on the other? Correct judgements should help us to attain knowledge. If we want to know whether the noise that we heard was a gunshot, we are not engaged in a game of guessing, but rather we are trying to be as reasonable as possible about the probability that it was in fact a real gunshot. What is it that makes our judgement correct, if it is not the correspondence with a real object or fact?

Brentano tries to capture this more demanding notion of correctness with his notion of “self-evidence.” He points out that the judgement of a subject can be true even if it is not self-evident to that subject. This leaves open the possibility that it is evident to another subject whose judgement would then be correct. Suppose your judgement is that John is happy. You may have good reasons for judging so, but the truth of this judgement is not self-evident to you. There is however a person, John, who might be able to judge with self-evidence that he is happy right now. To say that your judgement is true means that it agrees with the judgement of John when asked whether he is happy or not.

But what about judgements like “Jack has won the lottery”? In this case we can ask the company running the lottery whether this assertion is true, but we will find no one in a position to resolve this question in a self-evident judgement. How then can Brentano’s definition be considered a general definition of truth that applies to all judgements?

It is at this point that the distinction between a definition of truth and a principle of concept acquisition becomes crucial. When we ask how we acquire the concept of truth, the slogan “Correctness First!” tells us that we acquire the concept of truth only later: the first step is to recognize that judging with self-evidence means to judge correctly (see Textor 2019). But we must not conclude from this that the slogan also applies when we define the concept of truth. Towards the end of his lecture “On the Concept of Truth” Brentano notices that one can remove the notion of “correspondence” from the classical Aristotelian definition of truth, without making it incomprehensible or false. “A judgement of the form ‘A exists’ is true if and only if A exists; a judgement of the form ‘A does not exist’ is true if A does not exist.” Was Brentano then a pioneer of a minimalist theory of truth? It has been argued that this is at least an interesting alternative to the epistemological interpretation described above (see Brandl, 2017). It explains why Brentano in his lecture on the concept of truth finds it unproblematic that a definition of truth may seem trivial. In doing so, he allows that a definition need not be informative about how we acquire the concept of truth.

c. Interest and the Good

The distinction between defining a concept and explaining how we acquire that concept also plays a role in Brentano’s meta-ethical theory of correctness. A few months before his lecture on the concept of truth, the Viennese Law Society had asked Brentano to present his views on whether there was such a thing as a natural sense of justice. In his lecture “On the Origin of our Knowledge of Right and Wrong” (1889), Brentano gives a positive answer to the question posed by the Society, but he makes it clear that the term “natural sense” can be understood in different ways. For him, it is not an innate ability to see what is just or unjust. Rather, what Brentano is defending is the idea that there are “rules which can be known to be right and binding, in and for themselves, and by virtue of their own nature” (Brentano, 1889, p.3).

Brentano’s meta-ethical theory of right and wrong can therefore be seen as a close cousin of his theory of truth. It is a highly original theory because it steers a middle course between the empirical sentimentalism of Hume and the a priori rationalism of Kant. Brentano carves out a third option by asking: What are the phenomena of interest (as Brentano calls them) that form the basis of our moral attitudes and decisions? Introducing the notion of “correct love,” he proposes the following principle of concept acquisition: We acquire the concept of the good by abstracting it from instances of correct love. The term “love” here stands for a positive interest, in polar opposition to “hate,” which includes for Brentano any negative dis-interest. For Brentano, these are phenomena in the same category as simple feelings of benevolence, but with a more complex structure that makes them cognitively much more powerful. By introducing these more powerful notions, Brentano hopes to show how one can take a psychological approach in meta-ethics that still “radically and completely [breaks] with ethical subjectivism” (ibid., p. xi, transl. modified).

We have already mentioned that Brentano denies that our moral attitudes and decisions are based on an innate, and in this sense “natural,” instinct. It may be true that we instinctively love children and cute pets, and that these creatures fully deserve our caring response. But such instinctive or habitual responses can also be misleading. We may instinctively or habitually love things that do not deserve our love, for example if we have become addicted to them. A theory that breaks with ethical subjectivism must be able to tell us why our love for children and pets is right and our love for a drug is wrong.

One way to approach this matter is to interpret Brentano as a precursor of a “fitting attitude” theory (see Kriegel 2017, p. 224ff). When we love an object that deserves our love, we may call this a “fitting attitude.” But to know what “fittingness” means, we have to turn to inner perception. Inner perception tells us, for example, when we love the kindness of a person, that this is a correct emotional response. Once we know that a person is kind, we know immediately that her kindness is something to be loved. This is “self-imposing,” as Kriegel says.

The question now is whether inner perception will also provide us with a list of preferences that is beyond doubt. For example, does inner perception tell us that being healthy or happy is better than being sick or sad, or as Brentano would put it: that it is correct to love health and happiness more than sickness or sadness? Such claims are open to counterexamples, or so it would seem. A person might want to get sick, or give in to sadness, or deliberately hurt herself. But there is a response Brentano can make to defend the self-imposing character of a preference-order. He could say that people have such deviant preferences only for the purpose of achieving some further goal. If we ask for good things that can be final goals, i.e. goals that we do not pursue for the sake of some other goal, then no one can reasonably doubt that health, happiness, and knowledge are better than sickness, sadness, and error.

Following this line, these cases could be treated in the same way as true judgements that are not self-evident to the subject making them: Even if it is not self-evident to a subject that health is a good, there may be subjects who take it as an ultimate goal and for whom it is a self-imposing good. Brentano can thus also claim to avoid a dilemma that threatens his meta-ethics: If goodness just depends on our emotional responses, this would make this notion fully subjective. But if it covers only those cases when the correctness of our love is self-evident to us, its domain of application would be very small indeed. Hence the idea that goodness must correlate with the responses of a perfect moral agent.

Brentano’s notion of correct love may explain how we acquire the concept of goodness, but it need not figure as part of a substantive definition of this concept. Cases of moral behavior whose correctness is self-imposing may still be informative, without comparing our moral behavior with an ideal moral agent. These cases suggest a preference order of goodness. For example, cases in which people sacrifice all their possessions to get medical treatment may help us to see why health is such a high good, perhaps even an ultimate good. And cases in which people risk their health for moral reasons may help us to see that there are goods that are ranked even higher than good health. Just as self-evident judgements lead us to the idea that truth is the highest epistemic value, so acts of love, whose correctness is self-imposing, can lead us to the idea of a supreme good.

d. Presentation and Beauty

Brentano concludes his analysis of normative concepts with an analysis of the concept of beauty. Extending his arguments against subjectivism, he attacks the common view that beauty exists only “in the eyes of the beholder.” For Brentano, beauty is a form of goodness that is no less objective than other forms of goodness. What the common view rightly points out is merely a fact about how we acquire the concept of beauty, namely by recourse to experience. Since this also holds for the concepts of truth and moral goodness, as Brentano says, beauty is no exception.

While we do not have a fully worked out version of Brentano’s aesthetic theory, its outlines are clear from lecture notes in his Nachlass (see Brentano: Grundzüge der Ästhetik, 1959). Again, taking a psychological approach, Brentano argues that it is not a simple form of pleasure that makes us see or feel the beauty of an object. Like in the case of moral judgements, it is a more complex mental state with a two-level structure. When we judge something to be beautiful, the first-level acts are acts of presentation: we perceive something or recall an image from memory. To this, we add a second-level phenomenon of interest: either “delight” or “disgust.” This gives us the following principle of concept acquisition: We acquire the concept of beauty by abstracting it from experiences of correct delight in a presentation.

Brentano’s theory nicely incorporates the fact that people differ in their aesthetic feelings. Musicians feel delight when hearing their favorite piece of music, art lovers when looking at a favorite painting, and nature lovers when enjoying a good view of the landscape. What they have in common is a particular kind of experience, which is why they can use the term “beautiful” in the same way. It is the experience of delight that underlies their understanding of beauty. Yet it is not a simple enjoyment like the pleasure we may feel when we indulge in ice cream or when we take a hot bath. Aesthetic delight is a response that requires a more reflective mode. To feel a higher-order pleasure, we must pay attention to the way objects appear to us and contemplate the peculiarities of these representations.

This reconstruction of Brentano’s aesthetic theory suggests that Brentano does not need a substantive definition of beauty. He can get by with general principles that connect the notions of beauty and delight, mimicking those that connect goodness with love, or truth with judgement and existence. As early as 1866, Brentano used this formulation of such a principle in its application to aesthetics: something is beautiful if its representation is the object of a correct emotion (see Brentano, “Habilitation Theses”). While these principles come with a sense of obviousness, interesting consequences follow from Brentano’s explanation of how we acquire our knowledge of them.

First, it follows that just as we can be mistaken in our judgements and emotional responses, so we can fail to appreciate the aesthetic qualities of an object. People may feel pleasure from things that do not warrant such pleasure, or they may fail to respond with pleasure to even the most beautiful things in front of their eyes. A plausible explanation for such cases of aesthetic incompetence is that people can perceive things very differently. They may not hear what the music lover hears, or fail to see what the nature lover sees, and therefore cannot understand why they find these things so pleasurable.

Second, Brentano’s theory implies that no relation of correspondence between mind and reality will explain what justifies aesthetic pleasure. Such justification can only come from inner perception, which provides us with exemplary cases of aesthetic delight. In such cases, like in the case of moral feelings, the correctness of the enjoyment is self-imposing. Such experiences may serve as a yardstick for judging cases whose beauty is less obvious and therefore more controversial.

4. Epistemology and Metaphysics

Brentano’s interest in questions of psychology is matched by an equally deep interest in questions of metaphysics. In both areas Brentano draws inspiration from Aristotle and the Aristotelian tradition. We can see this from his broad notion of metaphysics, encompassing ontological, cosmological, and theological questions. The central ontological question for Aristotle is the question of “being as such”; what does it mean to say that something is, is being, or has being? This is followed by questions concerning the categories of being, e.g.: What are the highest categories into which being can be divided? The second part of metaphysics, cosmology, seeks to establish the first principles of the cosmic order. It addresses questions concerning space, time and causality. Finally, the pinnacle of metaphysics is to be found in natural theology, which asks for the reason of all being: Does the world have a first cause, and does the order of the world suggest a wise and benevolent creator of the world?

For Brentano, as for Kant, these metaphysical questions pose an epistemological challenge first of all because they tend to exceed the limits of human understanding. To defend the possibility of metaphysical knowledge against skepticism, Brentano takes a preliminary step which he calls “Transcendental Philosophy,” but without adopting Kant’s Copernican turn. On the contrary, for Brentano, Kant himself counts as a skeptic because he declares things in themselves to be unknowable. What Kant overlooked, Brentano argues, is the self-evidence with which we make certain judgements. From this experience, he believes we can derive metaphysical principles whose validity is unquestionable.

a. Kinds of Knowledge

Skeptics of metaphysical knowledge often draw a contrast between metaphysical and scientific knowledge. Brentano resisted such an opposition, opting instead for an integration of scientific knowledge into metaphysics. He must therefore face the following conundrum: How can philosophy integrate the results obtained by the special sciences while at the same time making claims that go beyond the scope of any of the individual sciences?

Kant’s attempt to resolve this dilemma is based on the special nature of synthetic judgements a priori. Such judgements have empirical content, Kant holds, but we recognize them as true by the understanding alone, independently of sensory experience. Metaphysical knowledge thus becomes possible, but it is constrained by the scope of the synthetic judgements a priori. Brentano rejects this Kantian solution as inconclusive. Whatever a synthetic judgement a priori may be, it lacks what Brentano calls “self-evidence.” Metaphysics must not be constrained by such “blind prejudices,” Brentano holds.

Rejecting Kant’s view, Brentano proposes his own classification of judgements based on two distinctions: He divides judgements into those that are made with and without self-evidence, and he distinguishes between judgements that are purely assertive in character and apodictic (necessarily true or necessarily false) judgements. Knowledge in the narrow sense can only be found in judgements that are self-evident or that can be deduced from self-evident judgements. This does not mean, however, that non-evident judgements have no epistemic value for Brentano. To see this, we can replace the assertive/apodictic distinction with a distinction between purely empirical and not purely empirical judgements. Crossing this distinction with the evident/not-evident distinction gives us four possible kinds of knowledge:

- knowledge through self-evident purely empirical judgements

- knowledge through non-self-evident purely empirical judgements

- knowledge through self-evident not purely empirical judgements, and

- knowledge through non-self-evident not purely empirical judgements.

To the first category belong judgements of inner perception in which we acknowledge the existence of a current mental phenomenon. Such judgements are always made with self-evidence, according to Brentano. For instance, you immediately recognize the truth of “I am presently thinking about Socrates” when you do have such thoughts and therefore cannot reasonably doubt their existence.

Category 2 contains the non-self-evident empirical judgements, including all empirical hypotheses. These judgements differ in the degree of their confirmation, which is expressed in probability judgements. Although they lack self-evidence, Brentano allows that they may have what he calls “physical certainty.” Repeated observation may lead us to the certainty, for instance, that the sun will rise tomorrow. It is a judgement with a very high probability.

Category 3 contains apodictic universal judgements which, according to Brentano, are always negative in character. For instance, the true form of the law of excluded middle is not expressed by “for all x, either x is F or x is not-F,” but rather by the existential negative form: “there is no x which is F and not-F.” The truth of such a judgement is self-evident in a negative sense, i.e. it expresses the impossibility of acknowledging the conjunction of a property and its negation.

Finally, what about judgements in category 4? These judgements are similar to those which Kant classified as synthetic a priori. While Brentano denies that mathematical propositions fall into this category, taking them to be analytic and self-evident, he recognises a special status for judgements such as “Something red cannot possibly be blue” —that is, blue and red in the same place (see Brentano: Versuch über die Erkenntnis, p. 47). Or consider the judgement “It is impossible for parallels to cross”. These judgements are based on experiences described in the framework of commonsense psychology or Euclidean geometry. We can imagine alternative frameworks in which these judgements turn out to be false. But for practical reasons we can ignore this possibility and classify them as axioms and hence as knowledge.

Brentano’s official doctrine is that there are no degrees of evidence and that all axioms are self-evident judgements in category 3, despite the fact that many of them have been disputed. This puts a lot of pressure on explaining away these doubts as unjustified. Brentano was confident that this was a promising project and that it was the only way to show how metaphysics could aim at a form of wisdom that goes beyond the individual sciences. A more modest approach would emphasize the fact that axioms are not purely empirical judgements: they are part of conceptual frameworks like commonsense psychology or Euclidean geometry. These frameworks operate with relations (for example, of opposition or correlation) that may seem self-evident, but alternative frameworks in which other relations hold are conceivable. Treating axioms as knowledge in category 4 leads to a more modest epistemology, which might still serve metaphysics in the way Brentano conceived its role.

b. A World of Things

There are many possible answers to the question “What is the world made of?” The first task of ontology is therefore to compare the different possible answers and to provide criteria for choosing one ontology over another. After considering various options, Brentano settled on the view that the world is made of real things and nothing else. To emphasize that Brentano defends a particular version of realism, his view is called “Reism.”

To better understand Brentano’s Reism, it is necessary to follow his psychological approach. Crucial to Brentano’s view is the idea that irrealia cannot be primary objects of presentations. When we affirm something, we may mention all kinds of non-real entities. But the judgements we make must be based exclusively on presentations of real things. There are many terms that obscure this fact. Brentano calls these terms “linguistic fictions,” which give the false impression that our thoughts could also concern non-real entities. Brentano’s list of such misleading expressions is long:

One cannot make the being or nonbeing of a centaur an object [i.e. a primary object] as one can a centaur. […] Neither the present, past, nor future, neither present things, past things, nor future things, nor existence and non-existence, nor necessity, nor non-necessity, neither possibility nor impossibility, nor the necessary nor the non-necessary, neither the possible nor the impossible, neither truth nor falsity, neither the true nor the false, nor good nor bad. Nor can […] such abstractions as redness, shape, human nature, and the like, ever be the [primary] objects of a mental reference (F. Brentano: Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint, 1973, p. 294).

Commentators have spent a great deal of time examining the arguments Brentano uses to support his Reism (see Sauer 2017, p. 139). His method may be illustrated with the following example. Suppose that someone judges correctly:

Rain is likely to come.

Brentano proposes the following analysis of this statement:

Someone correctly acknowledges rain as a likely event.

This analysis shows that it is not the probability of rain that gets acknowledged, which would be something non-real. If the first statement is equivalent with the second, then the existence of a real thing is sufficient for the truth of both statements. This “truth-maker” is revealed in the second statement: It is a thinking thing that recognizes rain as an impending event, or, as Brentano says, a being that makes the judgement “rain exists” in the mode of the future and with some degree of probability.

With examples like this, Brentano inspired many philosophers in the analytic tradition to use linguistic analysis to promote ontological parsimony. Not many, however, would go as far as Brentano when it comes to analysing perceptual judgements. Brentano is committed to the view that in an act of perception there is only one real thing that must exist: the subject who enjoys the sensory experience. To defend this position, he relies on the following dictum: “What is real does not appear to us, and what appears to us is not real.”

Interpreting this dictum is a serious task. Does Brentano mean to say that all secondary qualities, such as colours, sounds and tastes, are not real because they are mere appearances? Or is he saying that secondary qualities have a special form of “phenomenal reality”? There seem to be good reasons counting against both claims. The phenomenal reality of colours, shapes and tastes counts against classifying them as “non-real,” and the deceptive character that appearances can have counts against a notion of “phenomenal reality” that applies to all appearances across the board. It is only by resolving such questions that a proper understanding of Brentano’s Reism can be achieved.

c. Substance and Accidents

Another classic theme in Aristotelian metaphysics is the relationship between substance and accidents, which include both properties as well as relations. Brentano divides substances into material and immaterial ones, and, in line with his reistic position, holds that both substances and accidents are real things in the broad sense of the word. Material substances are real because they exist independently of our sensory and mental activities. Mental substances, on the other hand, are real things because we innerly perceive them with self-evidence.

Both substances and accidents raise the question of how they exist in space and time. Let us start with space: Brentano holds on to the common view that material substances occupy portions of space (space regions), much in line with a container view of space. Extending this geometric view to mental substances, Brentano considers modeling them as points that occupy no location. To make sense of this idea, he introduces the limiting case of a zero-dimensional topology. It is a limiting case because the lack of any dimensions means that the totality of space in this topology is represented as a single point. Since, by definition, the totality of space does not exist in any other space, we get the desired result that a mental substance occupies no location. In a further step, Brentano then compares material substances with one- or multi-dimensional continua and argues that one can represent mental substances as boundaries of such continua without assigning them a location. This analogy between mental substances and points on the one hand, and material substances and one- or multidimensional continua on the other, forms the basis of Brentano’s version of substance dualism (on dualism, see below).

What about time? As in the case of space, Brentano represents points of time as boundaries of a continuum. With the exception of the now-point, they are fictions cum fundamentum in re, which Brentano sometimes also calls metaphysical parts. In contrast with space however, Brentano holds that time is not a real continuum. More precisely, it is an unfinished (unfertiges) continuum of which only the now-point is real. This makes Brentano a presentist about the reality of time. It is a view that seems counterintuitive since it implies that a temporal continuum, such as a melody, can only be perceived at the now point because, strictly speaking, your hearing and your awareness of hearing the melody cannot extend beyond the now point. Brentano’s solution to this problem was to argue for persistence in the tonal presentations of the melody through an original (that is, innate) association between these presentations. When you hear the fourth note of a melody, your presentations of the first three notes are retained, which accounts for the impression of time-consciousness (although technically there is no time consciousness). This account was very influential on Husserl (see Fréchette 2017 on Brentano’s conception of time-consciousness).

Now back to substance. We often characterize substantial change as a change of accidents inhering in a substance. For example, a substance may lose weight; a leaf on a tree may change its color from red to green, thereby losing an accident and gaining a new one. This common view is not Brentano’s view. On the contrary, for Brentano, spatial and temporal accidents are absolute accidents. This means that a substance cannot lose or gain any such properties. To make sense of this, Brentano does two things: first, he turns the traditional view of the substance-accident relation upside down. Instead of seeing the substance as a fundamental being and its accidents as inhering in it, Brentano changes the order: for him, accidents are more fundamental than substances. Second, he rejects inherence as a tie between substance and accident, and replaces it with the parthood relation: In his account, accidents are wholes of which a substance is a part. To illustrate this, take a glass of water which contains 200 ml of water at t1. After you have taken a sip from the glass, it then contains 170 ml of water at t2. According to Brentano, what changes are the wholes while the same substance is part of two different wholes at t1 and t2. Similarly, Brentano argues, when I heat the water in my cup, the water not only expands in space, but also takes up more or less “space” on a temporal continuum of thermal states. This temporal continuum of thermal states is also a continuum of wholes containing the same substance. Expansion does not require new properties to be added to a substance. It just requires an increase that is measurable on some continuum.

It did not escape Brentano that an Aristotelian realism about universals poses a serious problem. According to this view, universals exist in re, that is, not independently of the substances in which they occur. It follows, in the case of material substances, that an accident can exist in more than one place at the same time. It may also be that an accident ceases to exist altogether when all its instances disappear, but later begins to exist again as soon as there is a new instance in which it occurs.

At this point, one must consider again the role that Brentano assigns to linguistic analysis. Brentano relies on such an analysis when he interprets simple categorical judgements as existential judgements. This analysis should remove the root from which the problem of multiple existence arises. Consider, for example, the simple categorical judgement:

A. Some men are bald-headed.

Brentano reduces this judgement to the following existential judgement:

B. A bald-headed man exists.

In the categorical judgement A, the term “man” denotes a substance and the term “bald-headed” denotes an accident of that substance if the judgement is true. In the existential judgement B, we have a single complex term, “bald-headed man,” which corresponds to a complex presentation, independently of whether a bald man exists or not. The function of the judgement is to acknowledge the existence of the object presented in this way, without adding any further “tie” between substance and accident.

Brentano’s mereology provides us with an ontology that matches this semantic analysis. The idea is the following: The complex term “bald man” denotes a whole, which has two parts (“bald” and “man”), both of which seem to denote parts of this whole. Now, which is here the substance, and which is the accident? Brentano decides that only the term “man” denotes a substance, and only the complex term “bald-headed man” denotes an accident. This means a substance, say the man Socrates, can be part of a whole (e.g. the bald man Socrates) without there having to be another part which must be added to this substance in order for this whole to exist.

Brentano offers us an account of substance that is peculiar because it goes against the principle of supplementation in extensional mereology. Brentano doesn’t follow that intuition: For him, properties like “bald-headedness” are not further parts that add to the substance to make it a whole. He thereby corrects the Aristotelian form of realism about universals at the very point that raises the problem of multiple existence.

d. Dualism, Immortality, God

One of the oldest problems in metaphysics is the so-called “mind-body problem.” Brentano confronts this problem in a traditional as well as in a modern way. The traditional setting is provided by the Aristotelian doctrine that different forms of life are explained by the different kinds of souls that organisms possess. Plants and animals have embodied souls that form the lower levels of the human soul which also includes a “thinking soul” as a higher part. In this framework, the mind-body problem consists of two questions: (1) How do the lower parts of the human soul fulfil their body-bound function?; and (2) how, if at all, does the thinking soul depend on the body?

The modern setting of the mind-body problem is provided by Descartes’ arguments for the immateriality of the soul. These arguments make use of considerations that suggest that the activity of the mind is thinking, and that thinking requires a substance that thinks, but not a body with sensory organs. Following the Cartesian argument, the mind-body problem becomes primarily a problem of causation: (1) how can sensory processes have a causal effect on the thinking mind; and (2) how can our thoughts have a causal effect on our behavior?

Brentano’s ambitious aim in his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint was to bridge the gap between these two historical frameworks. If he succeeded, he would be able to use Cartesian ideas to answer questions arising within the Aristotelian framework, and he would be able to use Aristotelian ideas to answer questions about mental causation. But since Brentano left his Psychology unfinished, we do not know for sure how Brentano hoped to resolve the question, “whether it is conceivable that mental life continues after the dissolution of the body” (Brentano 1973, xxvii).

While Brentano did not get to the part of his Psychology that was meant to deal with the immortality question, he prepares this discussion in a chapter on the unity of consciousness. He begins with the following observation:

We are forced to take the multiplicity of the various acts of sensing […] as well as the inner perception which provides us with knowledge of all of them, as parts of one single phenomenon in which they are contained, as one single and unified thing (Brentano 1973, p. 97).

Here Brentano is only talking about the unity of the experience we have when, for example, we simultaneously hear and see a musician playing an instrument. But the same idea can be extended when we think about our own future. Suppose I am looking forward to a vacation trip I have planned. There is a special unity involved in this because I could be planning a trip without looking forward to it, and I could be looking forward to a trip that someone else is planning. In the present case, however, my intention and my joy are linked, and in a double way. Both phenomena relate to the same object: my future self that enjoys the trip. Using examples like this, an argument for the immortality of the soul could be made along the following lines:

- The unity I perceive between my intentions and the pleasures I feel now does not rely on any local part of my body.

- If it doesn’t rely on any part of my body now, it will not rely on my body in the future.

- Therefore, the unity I perceive now may well outlive my body.

While the question of immortality concerns the end of our life, there is also a question about its beginning: How does it come that each human being has an individual soul? Brentano takes up this question in a lengthy debate with the philologist and philosopher Eduard Zeller. The subject of this debate was whether Aristotle could be credited with the so-called “creationist” view, according to which the existence of each individual soul is due to God’s creation. Brentano affirms such an interpretation, and we may assume that it coincides with his own view of the matter. It is a view that presupposes a fundamental difference between human and non-human creatures, but also allows some continuity in the way souls enter the bodies of living creatures:

Lest this divine intercession should appear too incredible, Aristotle calls attention to the fact that the powers of the lower elements do not suffice for the genesis of any living being whatever. Rather, the forces of the heavenly substances participate in a certain way as a cause, thereby making such beings more godlike. The participation of the deity in the creation of man, therefore, has its analogy in the generation of lower life (Brentano 1978, 111ff.).

What this suggests is that individual souls of all kinds are created in such a way that God’s contribution to the process is recognisable. This is remarkable, because it means that the human soul owes its existence to a process of creation that is in many ways analogous to processes that enable the existence of plants and animals.

Such considerations fit nicely into the Aristotelian framework of the mind-body problem. Some scholars have therefore questioned whether Brentano could also advocate a Cartesian substance dualism. Dieter Münch for instance suggests that there are clear traces of a “monistic tendency” in Brentano (D. Münch, 1995/96, p. 137).

On the other hand, we also find in Brentano considerations that favor the Cartesian framework. For example, when Brentano offers a psychological proof of the existence of God, he follows closely in the footsteps of Descartes (On the Existence of God, sections 435-464). In this proof, Brentano criticizes what he calls an “Aristotelian semi-materialism,” and argues that the unity of consciousness is incompatible with any form of materialism. The tension between these arguments (which may have been modified somewhat by Brentano’s disciples) and the passages quoted above seems difficult to resolve. We may take this as a sign that the gap between the Aristotelian and Cartesian frameworks is too wide to be bridged (see Textor 2017).

5. History of Philosophy and Metaphilosophy

Brentano’s contributions to the history of philosophy are above all an expression of his metaphilosophical optimism. Brentano believed that philosophy develops according to a model that distinguishes phases of progress and phases of decline. Phases of progress are relatively rare and followed by much longer phases of decline. Only a few philosophers, such as Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, Leibniz and Descartes, fulfill the highest standards which Brentano applies. Nevertheless, he was optimistic that another phase of progress will come, and that it will provide concrete solutions to philosophical problems.

Brentano’s phase model is undoubtedly speculative. It is the result of his reflections on how to approach the history of philosophy. In his view, it makes a big difference whether one studies the history of philosophy as an historian or as a philosopher. Brentano tried to convey to his students the relevance of this distinction, and it is for this purpose that he most often invoked his phase model.

a. How to do History of Philosophy

In a lecture given to the Viennese Philosophical Society in 1888, entitled “On the Method of Historical Research in the Field of Philosophy” (a draft of which has been published in Franz Brentano: Geschichte der Philosophie der Neuzeit (1987, pp. 81-105)), Brentano hands out his recommendations for doing history of philosophy. One should “approach the author’s thought in a philosophical way,” he says. This requires two critical competences: a specific hermeneutic competence, and a broad understanding of the main currents of progress and decline in philosophy.

The hermeneutic competence Brentano requires “consists in allowing oneself to be penetrated, as it were, by the spirit of the philosopher whose teachings one is studying” (ibid., p. 90). In his debate with Zeller, Brentano uses this requirement as an argument against a purely historical interpretation of Aristotle’s texts:

One must try to resemble as closely as possible the spirit whose imperfectly expressed thoughts one wants to understand. In other words, one must prepare the way for understanding by first meeting the philosopher philosophically, before concluding as a historian (Brentano: Aristoteles’ Lehre vom Ursprung des menschlischen Geistes (1911), p. 165).

The second requirement, namely an awareness of the main currents structuring the development of philosophy, brings us back to Brentano’s phase model. Such models were popular among historians at Brentano’s time. One of these historians was Ernst von Lasaulx, whose lectures Brentano attended as a student in Munich (see Schäfer 2020). A few years later, Brentano came across Auguste Comte’s model and put it to critical examination (see Brentano’s lecture “The Four Phases of Philosophy and its Current State” (1895)).

Brentano believes that progress of philosophy results from a combination of metaphysical interest with a strictly scientific attitude. He therefore disagrees with Comte on three points. Firstly, Comte fails to notice the repetitive cycles of progress and decline. Secondly, he does not see the classical period of Greek philosophy as a phase in which philosophers were driven by a purely theoretical interest. And thirdly, Comte mistakenly believes that modern philosophy had to pass through a theological and metaphysical phase before it could enter its scientific phase.

The broad perspective that Brentano takes on the history of philosophy leads him to cast a shadow over all philosophers who belong to a phase of decline. But this is not the only form of criticism to be found in Brentano. There are also independent and highly illuminating discussions of the works of Thomas Reid and Ernst Mach, as well as profound criticisms of Windelband, Sigwart and other logicians of Brentano’s time. From today’s point of view, these are all important contributions to the history of philosophy.

b. Aristotle’s Worldview

For Brentano, the study of Aristotle’s works was a major source of inspiration and went hand in hand with the development of his own ideas. Almost all his works contain commentaries on Aristotle, often in the form of a fictitious dialogue in which Brentano tested the viability of his own ideas and sought support for his own views from a historical authority.

Brentano was concerned with Aristotle’s philosophy throughout his life, from his early writings on ontology (1862) and psychology (1867), through his debate with Eduard Zeller on the origin of the human soul (1883), to his treatise on Aristotle’s worldview a few years before his death. Throughout these studies, we can observe Brentano applying his hermeneutic method to fill in the gaps he finds in Aristotle’s argumentation and to resolve apparent contradictions.

In his final treatment of Aristotle, Brentano focuses on the doctrine of wisdom as the highest form of knowledge. He approaches this problem by not confining himself to what Aristotle says in the Metaphysics, but “by using incidental remarks from various works” (Aristotle and His World View, p. ix), and by including commentaries such as Theophrastus’s Metaphysics. With the help of Theophrastus and other sources, he hopes to resolve what he believes are only apparent contradictions in Aristotle’s writings. Brentano’s ultimate aim in these late texts is to present his own doctrine of wisdom as the highest form of knowledge (see the manuscripts published in the volume Über Aristoteles 1986).

Another thorny issue taken up by Brentano is Aristotle’s analysis of induction. Brentano praises Aristotle for having recognized the importance of induction for empirical knowledge when, for example, he discussed the question of how we can deduce the spherical shape of the moon from observing its phases. It was, however, “left for a much later age to shed full light, by means of the probability calculus, upon the theory of measure of justified confidence in induction and analogy” (Aristotle and his World View, p. 35). Brentano’s own attempt to solve the problem of induction is tentative. Its solution, he says, will depend on the extent to which the future mathematical analysis of the concept of probability coincides with the intuitive judgements of common sense (ibid.).

Brentano follows in Aristotle’s footsteps in treating metaphysics as a discipline that includes not only ontology, but also cosmology and (natural) theology. The pinnacle of metaphysics, for Brentano, would be a proof of the existence of God. Brentano already hints at this idea in his fifth habilitation thesis: “The multiplicity in the world refutes pantheism and the unity in it refutes atheism” (Brentano, 1867).

Brentano has worked extensively on a proof of God’s existence that relies both on a priori and a posteriori forms of reasoning (see Brentano: On the Existence of God. 1987). Here, too, it is not difficult to find the Aristotelian roots of Brentano’s thinking. In a manuscript from May 1901, Brentano writes: “Aristotle called theology the first philosophy because, just as God is the first among all things, the knowledge of God (in the factual, if not in the temporal order) is the first among all knowledge” (Religion and Philosophy, 90).