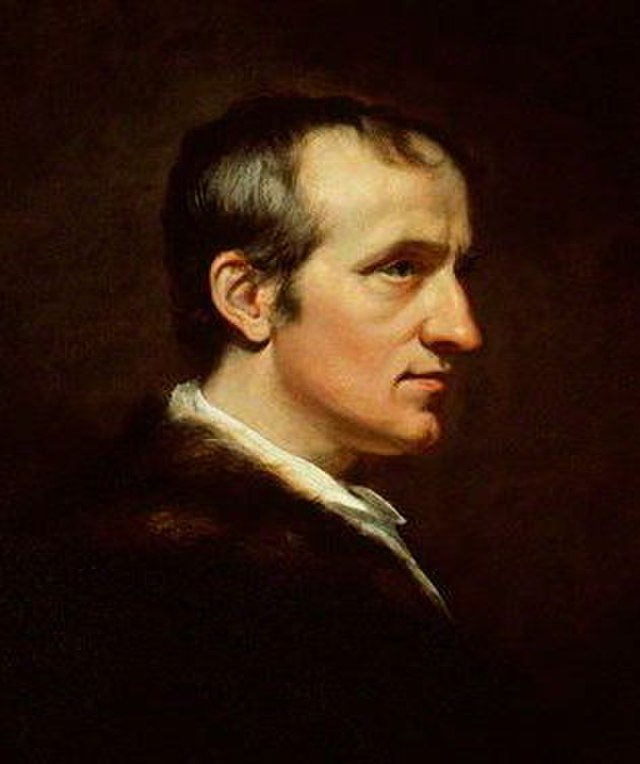

William Godwin (1756–1836)

Following the publication of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice in 1793 and his most successful novel, Caleb Williams, in 1794, William Godwin was briefly celebrated as the most influential English thinker of the age. At the time of his marriage to the writer Mary Wollstonecraft in 1797, the achievements and influence of both writers, as well as their personal happiness together, seemed likely to extend into the new century. It was not to be. The war with revolutionary France and the rise of a new spirit of patriotic fervour turned opinion against reformers, and it targeted Godwin. Following her death in September 1797, a few days after the birth of a daughter, Mary, Godwin published a candid memoir of Wollstonecraft that ignited a propaganda campaign against them both and which became increasingly strident. He published a third edition of Political Justice and a second major novel, St. Leon, but the tide was clearly turning. And while he continued writing into old age, he never again achieved the success, nor the financial security, he had enjoyed in the 1790s. Today he is most often referenced as the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft, as the father of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (the author of Frankenstein and The Last Man), and as the founding father of philosophical anarchism. He also deserves to be remembered as a significant philosopher of education.

Following the publication of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice in 1793 and his most successful novel, Caleb Williams, in 1794, William Godwin was briefly celebrated as the most influential English thinker of the age. At the time of his marriage to the writer Mary Wollstonecraft in 1797, the achievements and influence of both writers, as well as their personal happiness together, seemed likely to extend into the new century. It was not to be. The war with revolutionary France and the rise of a new spirit of patriotic fervour turned opinion against reformers, and it targeted Godwin. Following her death in September 1797, a few days after the birth of a daughter, Mary, Godwin published a candid memoir of Wollstonecraft that ignited a propaganda campaign against them both and which became increasingly strident. He published a third edition of Political Justice and a second major novel, St. Leon, but the tide was clearly turning. And while he continued writing into old age, he never again achieved the success, nor the financial security, he had enjoyed in the 1790s. Today he is most often referenced as the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft, as the father of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (the author of Frankenstein and The Last Man), and as the founding father of philosophical anarchism. He also deserves to be remembered as a significant philosopher of education.

In An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, Godwin argues that individuals have the power to free themselves from the intellectual and social restrictions imposed by government and state institutions. The argument starts with the very demanding requirement that we assess options impartially and rationally. We should act only according to a conviction that arises from a conscientious assessment of what would contribute most to the general good. Incorporated in the argument are principles of impartiality, utility, duty, benevolence, perfectionism, and, crucially, independent private judgment.

Godwin insists that we are not free, morally or rationally, to make whatever choices we like. He subscribes to a form of necessitarianism, but he also believes that choices are constrained by duty and that one’s duty is always to put the general good first. Duties precede rights; rights are simply claims we make on people who have duties towards us. Ultimately, it is the priority of the principle of independent private judgment that produces Godwin’s approach to education, to law and punishment, to government, and to property. Independent private judgment generates truth, and therefore virtue, benevolence, justice, and happiness. Anything that inhibits it, such as political institutions or modes of government, must be replaced by progressively improved social practices.

When Godwin first started An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, he intended it to explore how government can best benefit humanity. He and the publisher George Robinson wanted to catch the wave of interest created by the French Revolution itself and by Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, which so provoked British supporters of the revolution. Robinson agreed to support Godwin financially while he worked, with the understanding that he would send sections of the work as he completed them. This meant that the first chapters were printed before he had fully realised the implications of his arguments. The inconsistencies that resulted were addressed in subsequent editions. His philosophical ideas were further revised and developed in The Enquirer (1797), Thoughts Occasioned by a Perusal of Dr. Parr’s Spital Sermon (1801), Of Population (1820), and Thoughts on Man (1831), and in his novels. He also wrote several works of history and biography, and wrote or edited several texts for children, which were published by the Juvenile Library that he started with his second wife, Mary Jane Clairmont.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Godwin’s Philosophy: An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice

- Educational Implications of Godwin’s philosophy

- Godwin’s Philosophical Anarchism

- Godwin’s Fiction

- Conclusion

- References and Further Reading

1. Life

William Godwin was born in 1756 in Wisbech in Cambridgeshire, England, the seventh of thirteen children. His father was a Dissenting minister; his mother was the daughter of a successful shipowner. Godwin was fond of his lively mother, less so of his strictly Calvinist father. He was a pious and academically precocious boy, readily acquiring a close knowledge of the Old and New Testaments. After three years at a local school, where he read widely, learned some Latin and developed a passion for the classics, he moved at the age of 11 to Norwich to become the only pupil of the Reverend Samuel Newton. Newton was an adherent of Sandemanianism, a particularly strict form of Calvinism. Godwin found him pedantic and unjustly critical. The Calvinist doctrines of original sin and predestination weighed heavily. Calvinism left emotional scars, but it influenced his thinking. This was evidenced, Godwin later stated, in the errors of the first edition of Political Justice: its tendency to stoicism regarding pleasure and pain, and the inattention to feeling and private affections.

After a period as an assistant teacher of writing and arithmetic, Godwin began to develop his own ideas about education and to take an interest in contemporary politics. When William’s father died in 1772, his mother paid for her clever son to attend the New College, a Dissenting Academy in Hoxton, north of the City of London. By then Godwin had become, somewhat awkwardly, a Tory, a supporter of the aristocratic ruling class. Dissenters generally supported the Whigs, not least because they opposed the Test Acts, which prohibited anyone who was not an Anglican communicant from holding a public office. At Hoxton Godwin received a more comprehensive higher education than he would have received at Oxford or Cambridge universities (from which Dissenters were effectively barred). The pedagogy was liberal, based on free enquiry, and the curriculum was wide-ranging, covering psychology, ethics, politics, theology, philosophy, science, and mathematics. Hoxton introduced Godwin to the rational dissenting creeds, Socinianism and Unitarianism, to which philosophers and political reformers such as Joseph Priestley and Richard Price subscribed.

Godwin seems to have graduated from Hoxton with both his Sandemanianism and Toryism in place. But the speeches of Edmund Burke and Charles James Fox, the leading liberal Whigs, impressed him and his political opinions began to change. After several attempts to become a Dissenting minister, he accepted that congregations simply did not take to him; and his religious views began a journey through deism to atheism. He was influenced by his reading of the French philosophes. He settled in London, aiming to make a living from writing, and had some early encouragement. Having already completed a biography of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, he now contributed reviews to the English Review and published a collection of sermons. By 1784 he had published three minor novels, all quite favourably reviewed, and a satirical pamphlet entitled The Herald of Literature, a collection of spoof ‘extracts’ from works purporting to be by contemporary writers. He also contemplated a career in education, for in July 1783 he published a prospectus for a small school that he planned to open in Epsom, Surrey.

For the next several years Godwin was able to earn a modest living as a writer, thanks in part to his former teacher at Hoxton, Andrew Kippis, who commissioned him to write on British and Foreign History for the New Annual Register. The work built him a reputation as a competent political commentator and introduced him to a circle of liberal Whig politicians, publishers, actors, artists, and authors. Then, in 1789, events in France raised hopes for radical reform in Great Britain. On November 4 Godwin was present at a sermon delivered by Richard Price which, while primarily celebrating the Glorious Revolution of 1688, anticipated many of the themes of Political Justice: universal justice and benevolence; rationalism; and a war on ignorance, intolerance, persecution, and slavery. The special significance of the sermon is that it roused Edmund Burke to write Reflections on the Revolution in France, which was published in November 1790. Godwin had admired Burke, and he was disappointed by this furious attack on the Revolution and by its support for custom, tradition, and aristocracy.

He was not alone in his disappointment. Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, and Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Men were early responses to Burke. Godwin proposed to his publisher, George Robinson, a treatise on political principles, and Robinson agreed to sponsor him while he wrote it. Godwin’s ideas veered over the sixteen months of writing towards the philosophical anarchism for which the work is best known.

Political Justice, as Godwin declared in the preface, was the child of the French Revolution. As he finished writing it in January 1793, the French Republic declared war on the Kingdom of Great Britain. It was not the safest time for an anti-monarchist, anti-aristocracy, anti-government treatise to appear. Prime Minister William Pitt thought the two volumes too expensive to attract a mass readership; otherwise, the Government might have prosecuted Godwin and Robinson for sedition. In fact, the book sold well and immediately boosted Godwin’s fame and reputation. It was enthusiastically reviewed in much of the press and keenly welcomed by radicals and Dissenters. Among his many new admirers were young writers with whom Godwin soon became acquainted: William Wordsworth, Robert Southey, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and a very youthful William Hazlitt.

In 1794 Godwin wrote two works that were impressive and successful in different ways. The novel Things as They Are: or The Adventures of Caleb Williams stands out as an original exploration of human psychology and the wrongs of society. Cursory Strictures on the Charge delivered by Lord Chief Justice Eyre to the Grand Jury first appeared in the Morning Chronicle newspaper. Pitt’s administration had become increasingly repressive, charging supporters of British reform societies with sedition. On May 12, 1794, Thomas Hardy, the chair of the London Corresponding Society (LCS), was arrested and committed with six others to the Tower of London; then John Thelwall, a radical lecturer, and John Horne Tooke, a leading light in the Society for Constitutional Information (SCI), were arrested. The charge was High Treason, and the potential penalty was death. Habeas Corpus had been suspended, and the trials did not begin until October. Godwin had attended reform meetings and knew these men. He was especially close to Thomas Holcroft, the novelist and playwright. Godwin argued in Cursory Strictures that there was no evidence that the LCS and SCI were involved in any seditious plots, and he accused Lord Chief Justice Eyre of expanding the definition of treason to include mere criticism of the government. ‘This is the most important crisis in the history of English liberty,’ he concluded. Hardy was called to trial on October 25, and, after twelve days, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. Subsequently, Horne Tooke and Thelwall were tried and acquitted, and others were dismissed. Godwin’s article was considered decisive in undermining the charge of sedition. In Hazlitt’s view, Godwin had saved the lives of twelve innocent men (Hazlitt, 2000: 290). The collapse of the Treason Trials caused a surge of hope for reform, but a division between middle-class intellectuals and the leaders of labouring class agitation hastened the decline of British Jacobinism. This did not, however, end the anti-Jacobin propaganda campaign, nor the satirical attacks on Godwin himself.

A series of essays, published as The Enquirer: Reflections on Education, Manners and Literature (1797), developed a position on education equally opposed to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s progressivism (in Emile) and to traditional education. Other essays modified or developed ideas from Political Justice. One essay, ‘Of English Style’, describes clarity and propriety of style as the ‘transparent envelope’ of thoughts. Another essay, ‘Of Avarice and Profusion’, prompted the Rev. Thomas Malthus to respond with his An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798).

At the lodgings of a mutual friend, the writer Mary Hays, Godwin became reacquainted with a woman he had first met in 1791 at one of the publisher Joseph Johnson’s regular dinners, when he had wanted to converse with Thomas Paine rather than with her. Since then, Mary Wollstonecraft had spent time in revolutionary Paris, fallen in love with an American businessman, Gilbert Imlay, and given birth to a daughter, Fanny. Imlay first left her then sent her on a business mission to Scandinavia. This led to the publication of Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (1796). She had completed A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, a more substantial work than her earlier A Vindication of the Rights of Men. She had also recently survived a second attempt at suicide. Having previously published Mary: A Fiction in 1788, she was working on a second novel, The Wrongs of Woman: or, Maria. A friendship soon became a courtship. When Mary became pregnant, they chose to get married and to brave the inevitable ridicule, both previously having condemned the institution of marriage (in Godwin’s view it was ‘the worst of monopolies’). They were married on March 29, 1797. They worked apart during daytime, Godwin in a rented room near their apartment in Somers Town, St. Pancras, north of central London, and came together in the evening.

Godwin enjoyed the dramatic change in his life: the unfamiliar affections and the semi-independent domesticity. Their daughter was born on August 30. The birth itself went well but the placenta had broken apart in the womb; a doctor was called to remove it, and an infection took hold. Mary died on September 10. At the end she said of Godwin that he was ‘the kindest, best man in the world’. Heartbroken, he wrote that he could see no prospect of future happiness: ‘I firmly believe that there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy’. He could not bring himself to attend the funeral in the churchyard of St. Pancras Church, where just a few months earlier they had married.

Godwin quickly threw himself into writing a memoir of Wollstonecraft’s life. Within a few weeks he had completed a work for which he was ridiculed at the time, and for which he has been criticised by historians who feel that it delayed the progress of women’s rights. The Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798) is a tender tribute, and a frank attempt to explore his own feelings, but Godwin’s commitment to complete candour meant that he underestimated, or was insensitive to, the likely consequence of revealing ‘disreputable’ details of Mary’s past, not least that Fanny had been born out of wedlock. It was a gift to moralists, humourists, and government propagandists.

Godwin was now a widower with a baby, Mary, and a toddler, Fanny, to care for. With help from a nursemaid and, subsequently, a housekeeper, he settled into the role of affectionate father and patient home educator. However, he retained a daily routine of writing, reading, and conversation. A new novel was to prove almost as successful as Caleb Williams. This was St. Leon: A Tale of the Sixteenth Century. It is the story of an ambitious nobleman disgraced by greed and an addiction to gambling, then alienated from society by the character-corrupting acquisition of alchemical secrets. It is also the story of the tragic loss of an exceptional wife and of domestic happiness: it has been seen as a tribute to Wollstonecraft and as a correction to the neglect of the affections in Political Justice.

The reaction against Godwin continued into the new century, with satirical attacks coming from all sides. It was not until he read a serious attack by his friend Dr. Samuel Parr that he was stung into a whole-hearted defence, engaging also with criticisms by James Mackintosh and Thomas Malthus. Thoughts Occasioned by the Perusal of Dr. Parr’s Spital Sermon was published in 1801. His replies to Mackintosh and Malthus were measured, but his response to Parr was more problematic, making concessions that could be seen as undermining the close connection between truth and justice that is crucial to the argument of Political Justice.

Since Mary Wollstonecraft’s death, Godwin had acquired several new friends, including Charles and Mary Lamb, but he clearly missed the domesticity he had enjoyed so briefly; and he needed a mother for the girls. The story goes that Godwin first encountered his second wife in May 1801, shortly before he started work on the reply to Dr. Parr. He was sitting reading on his balcony when he was hailed from next door: ‘Is it possible that I behold the immortal Godwin?’ Mary Jane Clairmont had two children, Charles and Jane, who were similar in age to Fanny and Mary. Godwin’s friends largely disapproved – they found Mary Jane bad-tempered and artificial – but Godwin married her, and their partnership endured until his death.

Godwin had a moderate success with a Life of Chaucer, failed badly as a dramatist, and completed another novel, Fleetwood, or the New Man of Feeling (1805), but he was not earning enough to provide for his family by his pen alone. He and Mary Jane conceived the idea of starting a children’s bookshop and publishing business. For several years the Juvenile Library supplied stationery and books of all sorts for children and schools, including history books and story collections written or edited by ‘Edward Baldwin’, Godwin’s own name being considered too notorious. Despite some publishing successes, such as Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, the bookshop never really prospered. As he slipped into serious debt, Godwin felt he was slipping also into obscurity. In 1809 he wrote an Essay on Sepulchres: A Proposal for Erecting some Memorial of the Illustrious Dead in All Ages on the Spot where their Remains have been Interred. The Essay was generally well-received, but the proposal was ignored. With the Juvenile Library on the point of collapse, the family needed a benefactor who could bring them financial security.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was just twenty, recently expelled from Oxford University for atheism, and newly married and disinherited, when in January 1812 he wrote a fan letter to a philosopher he had not been sure was still living. His reading of Political Justice at school had ‘opened to my mind fresh & more extensive views’, he wrote. Shelley went off to Ireland to agitate for independence and distribute his pamphlet An Address to the Irish People. Godwin disapproved of the inflammatory tone, but invited Shelley and his wife, Harriet, to London. They eventually arrived in October and Shelley and Godwin thereafter maintained a friendly correspondence. Shelley’s first major poem, Queen Mab, with its Godwinian themes and references, was published at this time. During 1813, as he and Shelley continued to meet, Godwin saw a good deal of a new friend and admirer, Robert Owen, the reforming entrepreneur and philanthropist. Hazlitt commented that Owen’s ideas of Universal Benevolence, the Omnipotence of Truth and the Perfectibility of Human Nature were exactly those of Political Justice. Others thought Owen’s ‘socialism’ was Godwinianism by another name. As Godwin pleaded with friends and admirers for loans and deferrals to help keep the business afloat, the prospect of a major loan from Shelley was thwarted by Sir Timothy Shelley withholding his son’s inheritance when he turned twenty-one.

Godwin’s troubles took a different turn when Mary Godwin, aged sixteen, returned from a stay with friends in Scotland looking healthy and pretty. Harriet Shelley was in Bath with a baby. Shelley dined frequently with the Godwins and took walks with Mary and Jane. Soon he was dedicating an ode to ‘Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin’. On June 26th Mary declared her love as they lay together in St. Pancras Churchyard, beside her mother’s grave, Jane lingering nearby. By July Shelley had informed Harriet that he had only ever loved her as a brother. Godwin was appalled and remonstrated angrily, but early on the morning of July 28 he found a letter on his dressing table: Mary had eloped with Shelley, and they had taken Jane with them.

Godwin’s life over the next eight years, until Shelley’s tragic death in 1822, was far less dramatic or romantic than those of Mary and Shelley, or of Claire (as Jane now called herself). Their travels in Europe, the births and deaths of several children, including Claire’s daughter by Lord Byron, the precocious literary achievements (Shelley’s poems and Mary’s novel Frankenstein) are well known. Meanwhile, in London, Mary Wollstonecraft’s daughter, Fanny, was left unhappily behind. The atmosphere at home was tense and gloomy. Godwin refused to meet Mary and her lover until they were married, although the estrangement did not stop him accepting money from Shelley. A protracted struggle ensued, with neither party appearing to live up to Godwinian standards of candour and disinterestedness. Then, in October 1816, Fanny left the family home, ostensibly to travel to Ireland to visit her aunts (Wollstonecraft’s sisters). In Swansea, she killed herself by taking an overdose of laudanum. She was buried in an unnamed pauper’s grave, Godwin being fearful of further scandal connected with himself and Wollstonecraft. Shortly after this, Harriet Shelley’s body was pulled from the Serpentine in London. Shelley and Mary could now marry, and before long they escaped to Italy, with Claire (Jane) still in tow.

Despite these troubles and the precarious position of the Juvenile Library, Godwin managed to complete another novel, Mandeville, A Tale of the Seventeenth Century in England (1817). He took pride in his daughter’s novel and in his son-in-law’s use of Godwinian ideas in his poems. At the end of 1817, Godwin began his fullest response to Malthus. It took him three years of difficult research to complete Of Population. Meanwhile, his financial difficulties had reached a crisis point. He besieged Shelley in Italy with desperate requests to fulfil his promised commitments, but Shelley had lost patience and refused. The money he had already given, he complained, ‘might as well have been thrown into the sea’. A brief reprieve allowed the Godwins to move, with the Juvenile Library, to better premises. Then came the tragedy of July 8th, 1822. Shelley drowned in rough seas in the Gulf of La Spezia. Mary Shelley returned to England in 1823 to live by her pen. In 1826 she published The Last Man, a work, set in the twenty-first century, in which an English monarch becomes a popular republican leader only to survive a world-wide pandemic as the last man left alive. Godwin’s influence is seen in the ambition and originality of her speculative fiction.

Godwin himself worked for the next five years on a four-volume History of the Commonwealth—the period between the execution in 1649 of Charles I and the restoration in 1660 of Charles II. He describes the liberty that Cromwell and the Parliamentarians represented as a means, not an end in itself; the end is the interests and happiness of the whole: ‘But, unfortunately, men in all ages are the creatures of passions, perpetually prompting them to defy the rein, and break loose from the dictates of sobriety and speculation.’

In 1825, Godwin was finally declared bankrupt, and he and Mary Jane were relieved of the burden of the Juvenile Library. They moved to cheaper accommodation. Godwin had the comfort of good relations with his daughter and grandson. He hoped for an academic position with University College, which Jeremy Bentham had recently helped to establish, but was disappointed. He worked on two further novels, Cloudesley and Deloraine. In 1831 came Thoughts on Man, a collection of essays in which he revisited familiar philosophical topics. In 1834, the last work to appear in his lifetime was published. Lives of the Necromancers is a history of superstition, magic, and credulity, in which Godwin laments that we make ourselves ‘passive and terrified slaves of the creatures of our imagination’. A collection of essays on religion, published posthumously, made similar points but commended a religious sense of awe and wonder in the presence of nature.

The 1832 Reform Bill’s extension of the male franchise pleased Godwin. In 1833, the Whig government awarded him a pension of £200 a year and a residence in New Palace Yard, within the Palace of Westminster parliamentary estate—an odd residence for an anarchist. When the Palace of Westminster was largely destroyed by fire, in October 1834, the new Tory Government renewed his pension, even though he had been responsible for fire safety at Westminster and the upkeep of the fire engine. He spent the last years of his life in relative security with Mary Jane, mourning the deaths of old friends and meeting a new generation of writers. He died at the age of eighty on April 7, 1836. He was buried in St. Pancras Churchyard, in the same grave as Mary Wollstonecraft. When Mary Shelley died in 1851, her son and his wife had Godwin’s and Wollstonecraft’s remains reburied with her in the graveyard of St. Peter’s Church in Bournemouth, on the south coast.

2. Godwin’s Philosophy: An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice

Note: references to An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (PJ) give the volume number and page number of the two volume 1798 third edition, which is the same as the 1946 University of Toronto Press, ed. F. E. L. Priestley, facsimile edition. This is followed by the book and chapter number of the first edition (for example, PJ II: 497; Bk VIII, vi). Page numbers of other works are those of the first edition.

a. Summary of Principles

The first edition of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice was published in 1793. A second edition was published in 1796 and a third in 1798. Despite the modifications in the later editions, Godwin considered ‘the spirit and the great outlines of the work remain untouched’ (PJ I, xv; Preface to second edition). Arguably, he was underplaying the significance of the changes. They make clear that pleasure and pain are the only bases on which morality can rest, that feeling, rather than reason or judgment, is what motivates action, and that private affections have a legitimate place in our rational deliberations.

The modifications are incorporated in the ‘Summary of Principles’ (SP) that he added to the start of the third edition (PJ I, xxiii–xxvii). The eight principles are:

(1) ‘The true object of moral and political disquisition, is pleasure or happiness.’ Godwin divides pleasures between those of the senses and those that are ‘probably more exquisite’, such as the pleasures of intellectual feeling, sympathy, and self-approbation. The most desirable and civilized state is that in which we have access to all these diverse sources of pleasure and possess a happiness ‘the most varied and uninterrupted’.

(2) ‘The most desirable condition of the human species, is a state of society.’ Although government was intended to secure us from injustice and violence, in practice it embodies and perpetuates them, inciting passions and producing oppression, despotism, war, and conquest.

(3) ‘The immediate object of government is security.’ But, in practice, the means adopted by government restrict individual independence, limiting self-approbation and our ability to be wise, useful, or happy. Therefore, the best kind of society is one in which there is as little as possible encroachment by government upon individual independence.

(4) ‘The true standard of the conduct of one man to another is justice.’ Justice is universal, it requires us to aim to produce the greatest possible sum of pleasure and happiness and to be impartial.

(5) ‘Duty is the mode of proceeding, which constitutes the best application of the capacity of the individual, to the general advantage.’ Rights are claims which derive from duties; they include claims on the forbearance of others.

(6) ‘The voluntary actions of men are under the direction of their feelings.’ Reason is a controlling and balancing faculty; it does not cause actions but regulates ‘according to the comparative worth it ascribes to different excitements’—therefore, it is the improvement of reason that will produce social improvements.

(7) ‘Reason depends for its clearness and strength upon the cultivation of knowledge.’ As improvement in knowledge is limitless, ‘human inventions, and modes of social existence, are susceptible of perpetual improvement’. Any institution that perpetuates particular modes of thinking or conditions of existence is pernicious.

(8) ‘The pleasures of intellectual feeling, and the pleasures of self-approbation, together with the right cultivation of all our pleasures, are connected with the soundness of understanding.’ Prejudices and falsehoods are incompatible with soundness of understanding, which is connected, rather, with free enquiry and free speech (subject only to the requirements of public security). It is also connected with simplicity of manners and leisure for intellectual self-improvement: consequently, an unequal distribution of property is not compatible with a just society.

b. From Private judgment to Political Justice

Godwin claims there is a reciprocal relationship between the political character of a nation and its people’s experience. He rejects Montesquieu’s suggestion that political character is caused by external contingencies such as the country’s climate. Initially, Godwin seems prepared to argue that good government produces virtuous people. He wants to establish that the political and moral character of a nation is not static; rather, it is capable of progressive change. Subsequently, he makes clear that a society of progressively virtuous people requires progressively less governmental interference. He is contesting Burke’s arguments for tradition and stability, but readers who hoped that Godwin would go on to argue for a rapid, or violent, revolution were to be disappointed. There is even a Burkean strain in his view that sudden change can risk undoing political and social progress by breaking the interdependency between people’s intellectual and emotional worlds and the social and political worlds they inhabit. He wants a gradual march of opinions and ideas. The restlessness he argues for is intellectual, and it is encouraged in individuals by education.

Unlike Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft in their responses to Burke, Godwin rejects the language of rights. Obligations precede rights and our fundamental obligation is to do what we can to benefit society as a whole. If we do that, we act justly; if we act with a view to benefit only ourselves or those closest to us, we act unjustly. A close family relationship is not a sufficient reason for a moral preference, nor is social rank. Individuals have moral value according to their potential utility. In a fire your duty would be to rescue someone like Archbishop Fénelon, a benefactor to humankind, rather than, say, a member of your own family. (Fénelon’s 1699 didactic novel The Adventures of Telemachus, Son of Ulysses criticised European monarchies and advocated universal brotherhood and human rights; it influenced Rousseau’s philosophy of education.) It seems, then, that it is the consequences of one’s actions that make them right or wrong, that Godwin’s moral philosophy is a form of utilitarianism. However, Mark Philp (1986) argues that Godwin’s position is more accurately characterised as a form of perfectionism: one’s intentions matter and these, crucially, are improvable.

What makes our intentions improvable is our capacity for private judgment. As Godwin has often been unfairly described, both in his own day and more recently, as a cold-hearted rationalist, it is important to clarify what he means by ‘judgment’. It involves a scrupulous process of weighing relevant considerations (beliefs, feelings, pleasures, alternative opinions, potential consequences) in order to reach a reasonable conclusion. In the third edition (SP 6–8), he implies that motivating force is not restricted to feelings (passions, desires), but includes preferences of all kinds. The reason/passion binary is resisted. An existing opinion or intellectual commitment might be described as a feeling, as something which pleases us and earns a place in the deliberative process. In his Reply to Parr, Godwin mentions that the choice of saving Fénelon could be viewed as motivated by the love of the man’s excellence or by an eagerness ‘to achieve and secure the welfare and improvement of millions’ (1801: 41). Furthermore, any kind of feeling that comes to mind thereby becomes ratiocinative or cognitive; the mind could not otherwise include it in the comparing and balancing process. Godwin rejects the reason/passion binary most explicitly in Book VIII of Political Justice, ‘On Property’. The word ‘passion’, he tells us, is mischievous, perpetually shifting its meaning. Intellectual processes that compare and balance preferences and other considerations are perfectible (improvable); the idea that passions cannot be corrected is absurd, he insists. The only alternative position would be that the deliberative process is epiphenomenal, something Godwin could not accept. (For the shifting meaning of ‘passion’ in this period, and its political significance, see Hewitt, 2017.)

Judgments are unavoidably individual in the sense that the combination of relevant considerations in a particular case is bound to be unique, and also in the sense that personal integrity and autonomy are built into the concept of judgment. If we have conscientiously weighed all the relevant considerations, we cannot be blamed for trusting our own judgment over that of others or the dictates of authority. Nothing—no person or institution, certainly not the government—can provide more perfect judgments. Only autonomous acts, Godwin insists, are moral acts, regardless of actual benefit. Individual judgments are fallible, but our capacity for good judgment is perfectible (SP 6). Although autonomous and impartial judgments might not produce an immediate consensus, conversations and a conscientious consideration of different points of view help us to refine our judgment and to converge on moral truths.

In the first edition of Political Justice, it is the mind’s predisposition for truth that motivates our judgments and actions; in later editions, when it is said to be feelings that motivate, justice still requires an exercise of impartiality, a divestment of our own predilections (SP 4). Any judgment that fails the impartiality test would not be virtuous because it would not be conducive to truth. Godwin is not distinguishing knowledge from mere belief by specifying truth and justified belief conditions; rather, he is specifying the conditions of virtuous judgments: they intentionally or consciously aim at truth and impartiality. A preference for the general good is the dominant motivating passion when judgments are good and actions virtuous. The inclusion in the deliberation process of all relevant feelings and preferences arises from the complexity involved in identifying the general good in particular circumstances. Impartiality demands that we consider different options conscientiously; it does not preclude sometimes judging it best to benefit our friends or family.

Is the development of human intellect a means to an end or an end in itself? Is it intrinsically good? Is it the means to achieving the good of humankind or is the good of humankind the development of intellect? If the means and the end are one and the same, then, as Mark Philp (1986) argues, Godwin cannot be counted, straightforwardly at least, a utilitarian, even though the principle of utility plays a major role in delineating moral actions. If actions and practices with the greatest possible utility are those which promote the development of human intellect, universal benevolence and happiness must consist in providing the conditions for intellectual enhancement and the widest possible diffusion of knowledge. The happiest and most just society would be the one that achieved this for all.

When the capacity for private judgment has been enhanced, and improvements in knowledge and understanding have been achieved, individuals will no longer require the various forms of coercion and constraint that government and law impose on them, and which currently inhibit intellectual autonomy (SP 3). In time, Godwin speculates, mind could be so enhanced in its capacities, that it will conquer physical processes such as sleep, even death. At the time he was mocked for such speculations, but their boldness is impressive, and science and medicine have greatly prolonged the average lifespan, farm equipment (as he foretold) really can plough fields without human control, and research continues into the feasibility (and desirability) of immortality.

Anticipating the arguments of John Stuart Mill, Godwin argues that truth is generated by intellectual liberty and the duty to speak candidly and sincerely in robust dialogue with others whose judgments differs from one’s own. Ultimately, a process of mutual individual and societal improvement would evolve, including changes in opinion. Godwin’s anarchistic vision of future society anticipates the removal of the barriers to intellectual equality and justice and the widest possible access to education and to knowledge.

3. Educational Implications of Godwin’s philosophy

a. Progressive Education

Godwin’s interest in progressive education was revealed as early as July 1783 when the Morning Herald published An Account of the Seminary. This was the prospectus for a school—‘For the Instruction of 12 Pupils in the Greek, Latin, French and English Languages’—that he planned to open in Epsom, Surrey. It is unusually philosophical for a school prospectus. It asserts, for example, that when children are born their minds are tabula rasa, blank sheets susceptible to impressions; that by nature we are equal; that freedom can be achieved by changing our modes of thinking; that moral dispositions and character derive from education and from ignorance. The school’s curriculum would focus on languages and history, but the ‘book of nature’ would be preferred to human compositions. The prospectus criticizes Rousseau’s system for its inflexibility and existing schools for failing to accommodate children’s pursuits to their capacities. Small group tuition would be preferred to Rousseauian solitary tutoring. Teachers would not be fearsome: ‘There is not in the world,’ Godwin writes, ‘a truer object of pity than a child terrified at every glance, and watching with anxious uncertainty the caprices of a pedagogue’. Although nothing transpired because too few pupils were recruited, the episode reveals how central education was becoming to Godwin’s political and social thinking. In the Index to the third edition of Political Justice, there are references to topics such as education’s effects on the human mind, arguments for and against a national education system, the danger of education being a producer of fixed opinions and a tool of national government. Discussions of epistemological, psychological, and political questions with implications for education are frequent. What follows aims to synthesize Godwin’s ideas about education and to draw out some implications.

Many of Godwin’s ideas about education are undoubtedly radical, but they are not easily assimilated into the child-centred progressivism that traces its origin back to Rousseau. Godwin, like Wollstonecraft, admired Rousseau’s work, but they both took issue with aspects of the model of education described in Emile, or On Education (1762). Rousseau believed a child’s capacity for rationality should be allowed to grow stage by stage, not be forced. Godwin sees the child as a rational soul from birth. The ability to make and to grasp inferences is essential to children’s nature, and social communication is essential to their flourishing. Children need to develop, and to refine, the communication and reasoning skills that will allow them to participate in conversations, to learn, and to start contributing to society’s progressive improvement. A collision of opinions in discussions refines judgment. This rules out a solitary education of the kind Emile experiences. Whatever intellectual advancement is achieved, diversity of opinion will always be a condition of social progress, and discussion, debate, disagreement (‘conversation’) will remain necessary in education.

Unlike Rousseau, Godwin does not appear to be especially concerned with stages of development, with limits to learning or reading at particular ages. He is not as concerned as Rousseau is about the danger of children being corrupted by what they encounter. We know that his own children read widely and were encouraged to write, to think critically, to be imaginative. They listened and learned from articulate visitors such as Coleridge. Godwin’s interest in children’s reading encouraged him to start the Juvenile Library. One publication was an English dictionary, to which Godwin prefixed A New Guide to the English Tongue. He hoped to inspire children with the inclination to ‘dissect’ their words, to be clear about the primary and secondary ideas they represent. The implication is that the development of linguistic judgment is closely connected with the development of epistemic judgment, with the capacity for conveying truths accurately and persuasively. The kind of interactive dialogue that he believes to be truth-conducive would require mutual trust and respect. There would be little point in discussion, in a collision of ideas, if one could not trust the other participants to exercise the same linguistic and epistemic virtues as oneself. Judgment might be private but education for Godwin is interpersonal.

A point on which Godwin and Rousseau agree is that children are not born in sin, nor do they have a propensity to evil. Godwin is explicit in connecting their development with the intellectual ethos of their early environment, the opinions that have had an impact on them when they were young. Some of these opinions are inevitably false and harmful, especially in societies in which a powerful hierarchy intends children to grow up taking inequalities for granted. As their opinions and thinking develop through early childhood to adulthood, it is important that individuals learn to think independently and critically in order to protect themselves from false and corrupt opinions.

Godwin does not advocate the kind of manipulative tutoring to which Rousseau’s Emile is subjected; nor does he distinguish between the capacities or needs of boys and girls in the way that Rousseau does in his discussion of the education appropriate to Emile’s future wife, Sophie. According to Rousseau, a woman is formed to please a man, to be subjected to him, and therefore requires an education appropriate to that role. Mary Wollstonecraft, in Chapter 3 of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, had similarly rejected Rousseau’s differentiation. Another difference is that, whereas Rousseau intends education to produce citizens who will contribute to an improved system of government, Godwin intends education to produce individuals with the independence of mind to contribute to a society that requires only minimal governmental or institutional superintendence.

b. Education, Epistemology, and Language.

Underlying Godwin’s educational thinking are important epistemological principles. In acquiring skills of communication, understanding, reasoning, discussion, and judgment, children acquire the virtue of complete sincerity or truthfulness. Learning is understanding, not memorisation. Understanding is the percipience of truth and requires sincere conviction. One cannot be said to have learned or to know or to have understood something, and one’s conduct cannot properly be guided by it, unless one has a sincere conviction of its truth. The connection between reason and conduct is crucial. Correct conduct is accessible to reason, to conscientious judgment. When they are given reasons for acting one way rather than another, children must be open to being convinced. This suggests that pedagogy should emphasise explanation and persuasion rather than monological direct instruction. Moral education is important in regard to conduct, but, as all education prepares individuals to contribute to the general good, all education is moral education.

Godwin gives an interesting analysis of the concept of truth, especially in the second and third editions of Political Justice. Children will need to learn that private judgment cannot guarantee truth. Not only are judgments clearly fallible, but—at least by the third edition—‘truth’ for Godwin does not indicate a transcendental idea, with an existence independent of human minds or propositions. ‘True’ propositions are always tentative, correctable on the basis of further evidence. The probability of a proposition being true can only be assessed by an active process of monitoring available evidence. Although Godwin frequently refers to truth, misleadingly perhaps, as ‘omnipotent’, he can only mean that the concept provides a standard, a degree of probability that precludes reasonable doubt. This suggests that ‘conviction’ is an epistemic judgment that there is sufficient probability to warrant avowal.

The reason why Godwin tends to emphasize truth rather than knowledge may be that we cannot transmit knowledge because we cannot transmit the rational conviction that would turn a reception of a truth into the epistemic achievement of knowing. Each recipient of truths must supply their own conviction via their own private judgment. Godwin insists that we should take no opinions on trust without independent thought and conviction. Judgments need to be refreshed to ensure that what was in the general interest previously still is. When we bind ourselves to the wisdom of our ancestors, to articles of faith or outdated teachings, we are inhibiting individual improvement and the general progress of knowledge. Conviction comes with a duty to bear witness, to pass on the truth clearly and candidly in ‘conversations’. The term ‘conversation’ implies a two-way, open-ended exchange, with at least the possibility of challenge. Integrity would not permit a proposition with an insufficient degree of probability to be conveyed without some indication of its lesser epistemic status, as with conjectures or hearsay. In modern terms, appreciating the difference in the epistemic commitments implicated by different speech acts, such as assertions, confessions, and speculations, would be important to the child’s acquisition of linguistic and epistemic skills or virtues.

c. Education, Volition, and Necessitarianism

Another aspect of Godwin’s philosophy that makes children’s education in reasoning and discussion important is his account of volition and voluntary choice. If a judgment produced no volition, it could be overruled by hidden or unconscious feelings or desires, and there would be no prospect of developing self-control. Disinterested deliberation would be a delusion and moral education would be powerless. Although Godwin made concessions concerning reason’s role in the motivation of judgments and actions, and in time developed doubts about the potential for improving the human capacity for impartiality, he did not alter the central point that it is thoughts that are present to mind, cognitive states with content, that play a role in motivation. Not all thoughts are inferences. By the time passions or desires, or any kind of preference, become objects of awareness, they are ratiocinative; the intellect is necessarily involved in emotion and desire. This ensures there is a point in developing critical thinking skills, in learning to compare and balance conscientiously whatever preferences and considerations are present to mind.

Godwin admits that some people are more able than others to conquer their appetites and desires; nevertheless, he thinks all humans share a common nature and can, potentially, achieve the same level of self-control, allowing judgment to dominate. This suggests that learning self-control should be an educational priority. Young people are capable of being improved, not by any form of manipulative training, coercion, or indoctrination, but by an education that promotes independence of mind through reflective reading and discussion. He is confident that a society freed from governmental institutions and power interests would strengthen individuals’ resistance to self-love and allow them to identify their own interests with the good of all. It would be through education that they would learn what constitutes the general good and, therefore, what their duties are. Although actions are virtuous that are motivated by a passion for the general good, they still require a foundation in knowledge and understanding.

The accusation that Godwin had too optimistic a view of the human capacity for disinterested rationality and self-control was one made by contemporaries, including Thomas Malthus. In later editions of Political Justice, reason is represented as a capacity for deliberative prudence, a capacity that can be developed and refined even to the extent of exercising control over sexual desire. Malthus doubted that most people would ever be capable of the kind of prudence and self-control that Godwin anticipated. Malthus’s arguments pointed towards a refusal to extend benevolence to the poor and oppressed, Godwin’s pointed towards generosity and equity.

The influence on Godwin’s perfectionism of the rational Dissenters, especially Richard Price and Joseph Priestley, is most apparent in the first edition of Political Justice. He took from them, and also from David Hartley and Jonathan Edwards, the doctrine of philosophical necessity, according to which a person’s life is part of a chain of causes extending through eternity ‘and through the whole period of his existence, in consequence of which it is impossible for him to act in any instance otherwise than he has acted’ (PJ I: 385; Bk IV, vi). Thoughts, and therefore judgments, are not exceptions: they succeed each other according to necessary laws. What stops us from being mere automatons is the fact that experience creates habits of mind which compose our moral and epistemic character, the degree of perfection in our weighing of preferences in pursuit of truth. The more rational, or perfect, our wills have become, the more they subordinate other considerations to truth. But the course of our lives, including our mental deliberations, is influenced by our desires and passions and by external intrusions, including by government, so to become autonomous we need to resist distortions and diversions. Experience and active participation in candid discussion help to develop our judgment and cognitive capacities, and as this process of improvement spreads through society, the need for government intervention and coercion reduces.

In revising this account of perfectionism and necessitarianism for the second and third editions of Political Justice, Godwin attempts to keep it compatible with the more positive role he then allows desire and passion. The language shifts towards a more Humean account of causation, whereby regularity and observed concurrences are all we are entitled to use in explanations and predictions, and patterns of feeling are more completely absorbed into our intellectual character. Godwin’s shift towards empiricism and scepticism is apparent, too, in the way truth loses much of its immutability and teleological attraction. This can be viewed as a reformulation rather than a diminution of reason, at least in so far as the changes do not diminish the importance of rational autonomy. We think and act autonomously, Godwin might say, when our judgments are in accordance with our character—that is, with our individual combination of moral and epistemic virtues and vices, which we maintain or improve by conscientiously monitoring and recalibrating our opinions and preferences. Autonomy requires that we do not escape the trajectory of our character but do try to improve it.

It is important to Godwin that we can make a conceptual distinction between voluntary and involuntary actions. He would not want young people to become fatalistic as a consequence of learning about scientific determinism, and yet he did not believe people should be blamed or made to suffer for their false opinions and bad actions: the complexity in the internal and environmental determinants of character is too great for that. Wordsworth for one accepted the compatibility of these positions. ‘Throw aside your books of chemistry,’ Hazlitt reports him saying to a student, ‘and read Godwin on Necessity’ (Hazlitt, 2000: 280).

d. Government, the State, and Education

For Godwin, progress towards the general good is delineated by progressive improvement in education and the development of private judgment. The general good is sometimes referred to by Godwin in utilitarian terms as ‘happiness’, although he avoids the Benthamite notion of the greatest happiness of the greatest number; and there is no question of pushpin being as good as poetry. A just society is a happy society for all, not just because individual people are contented but because they are contented for a particular reason: they enjoy a society, an egalitarian democracy, that allows them to use their education and intellectual development for the general good, including the good of future generations. A proper appreciation of the aims of education will be sufficient inspiration for children to want to learn; they will not require the extrinsic motivation of rewards and sanctions.

Godwin’s critique of forms of government, in Book V of Political Justice, is linked to their respective merits or demerits in relation to education. The best form of government is the one that ‘least impedes the activity and application of intellectual powers’ (PJ: II: 5; Bk V, i). A monarchy gives power to someone whose judgment and understanding have not been developed by vulnerability to the vicissitudes of fortune. All individuals need an education that provides not only access to books and conversation but also to experience of the diversity of minds and characters. The pampered, protected education of a prince inculcates epistemic vices such as intellectual arrogance and insouciance. He is likely to be misled by flatterers and be saved from rebellion only by the servility, credulity, and ignorance of the populace. No one person, not even an enlightened and virtuous despot, can match a deliberative assembly for breadth of knowledge and experience. A truly virtuous monarch, even an elected one, would immediately abolish the constitution that brought him to power. Any monarch is in the worst possible position to choose the best people for public office or to take responsibility for errors, and yet his subjects are expected to be guided by him rather than by justice and truth.

Similar arguments apply to aristocracies, to presidential systems, to any constitution that invests power in one person or class, that divides rulers from the people, including by a difference in access to education. Heredity cannot confer virtue or wisdom; only education, leisure and prosperity can explain differences of that kind. In a just society no one would be condemned to stupidity and vice. ‘The dissolution of aristocracy is equally in the interest of the oppressor and the oppressed. The one will be delivered from the listlessness of tyranny, and the other from brutalising operation of servitude’ (PJ II: 99; Bk V, xi).

Godwin recognises that democracy, too, has weaknesses, especially representative democracy. Uneducated people are likely to misjudge characters, be deceived by meretricious attractions or dazzled by eloquence. The solution is not epistocracy but an education for all that allows people to trust their own judgment, to find their own voice. Representative assemblies might play a temporary role, but when the people as a whole are more confident and well-informed, a direct democracy would be more ideal. Secret ballots encourage timidity and inconstancy, so decisions and elections should be decided by an open vote.

The close connection between Godwin’s ideas about education and his philosophical anarchism is clear. Had he been less sceptical about government involvement in education, he might have embraced more immediately implementable education policies. His optimism derives from a belief that the less interference there is by political institutions, the more likely people are to be persuaded by arguments and evidence to prefer virtue to vice, impartial justice to self-love. It is not the “whatever is, is right” optimism of Leibniz, Pope, Bolingbroke, Mandeville, and others; clearly, things can and should be better than they are. Complacency about the status quo benefits only the ruling elites. The state restricts reason by imposing false standards and self-interested values that limit the ordinary person’s sense of his or her potential mental capacities and contribution to society. Godwin’s recognition of a systemic denial of a voice to all but an elite suggests that his notion of political and educational injustice compares with what Miranda Fricker (2007) calls epistemic injustice. Social injustice for Godwin just is epistemic injustice in that social evils derive from ignorance, systemic prejudices, and inequalities of power; and epistemic injustice, ultimately, is educational injustice.

A major benefit of the future anarchistic society will be the reduction in drudgery and toil, and the increase in leisure time. Godwin recognises that the labouring classes especially are deprived of time in which to improve their minds. He welcomes technology such as printing, which helps to spread knowledge and literacy, but abhors such features of industrialisation as factories, the division of labour that makes single purpose machines of men, women, and children, and a commercial system that keeps the masses in poverty and makes a few opulently wealthy. Increased leisure and longevity create time for education and help to build the stock of educated and enlightened thinkers. Social and cultural improvement results from this accretion. Freed from governmental interference, education will benefit from a free press and increased exposure to a diversity of opinion. Godwin expresses ‘the belief that once freed from the bonds of outmoded ideas and educational practices, there was no limit to human abilities, to what men could do and achieve’ (Simon, 1960: 50). It is a mistake, Godwin writes towards the end of Political Justice, to assume that inequality in the distribution of what conduces to the well-being of all, education included, is recognised only by the ‘lower orders’. The beneficiaries of educational inequality, once brought to an appreciation of what constitutes justice, will inevitably initiate change. The diffusion of education will be initiated by an educated elite, but local discussion and reading groups will play a role: the educated and the less educated bearing witness to their own knowledge, passing it on and learning from frank conversation.

Unlike Paine and Wollstonecraft, Godwin does not advocate a planned national or state system of mass education. Neither the state nor the church could be trusted to develop curricula and pedagogical styles that educate children in an unbiased way. He is wary of the possibility of a mass education system levelling down, of reducing children to a “naked and savage equality” that suits the interests of the ruling elite. Nor could we trust state-accredited teachers to be unbiased or to model open-mindedness and explorative discussion. He puts his faith, rather, in the practices of a just community, one in which a moral duty to educate all children is enacted without restraint. Presumably, each community would evolve its own practices and make progressive improvements. The education of its children, and of adults, would find a place within the community’s exploration of how to thrive without government regulation and coercion. Paine wanted governmental involvement in a mass literacy movement, and Wollstonecraft wanted a system of coeducational schools for younger children, but Godwin sees a danger in any proposal that systematizes education.

Godwin’s vision of society does not allow him to specify in any detail a particular curriculum. Again, to do so would come too close to institutionalising education, inhibiting local democratic choice and diversity. He does, however, advocate epistemic practices which have pedagogical implications. Children should be taught to venerate truth, to enquire, to present reasons for belief, to reject as prejudice beliefs unsupported by evidence, to examine objections. ‘Refer them to reading, to conversation, to meditation; but teach them neither creeds nor catechisms, neither moral nor political’ (PJ II: 300; Bk VI, viii). In The Enquirer he writes: ‘It is probable that there is no one thing that it is of eminent importance for a child to learn. The true object of juvenile education, is to provide, against the age of five and twenty, a mind well regulated, active, and prepared to learn’ (1797: 77-78).

In the essay ‘Of Public and Private Education’, Godwin considers the advantages and disadvantages of education by private tutor rather than by public schooling. He concludes by wondering whether there might be a middle way: ‘Perhaps an adventurous and undaunted philosophy would lead to the rejecting them altogether, and pursuing the investigation of a mode totally dissimilar’ (1797: 64). His criticisms of both are reinforced in his novel Mandeville, in which the main character is educated privately by an evangelical minister, and then sent, unhappily, to Winchester College; he experiences both modes as an imposition on his liberty and natural dispositions. Certainly, Godwin’s ideas rule out traditional schools, with set timetables and curricula, with authoritarian teachers, ‘the worst of slaves’, whose only mode of teaching is direct instruction, and deferential pupils who ‘learn their lessons after the manner of parrots’ (1797: 81). The first task of a teacher, Godwin suggests in the essay ‘Of the Communication of Knowledge’, is to provide pupils with an intrinsic motive to learn—that is, with ‘a perception of the value of the thing learned’ (1797: 78). This is easiest if the teacher follows the pupil’s interests and facilitates his or her enquiries. The teacher’s task then is to smooth the pupil’s path, to be a consultant and a participant in discussions and debates, modelling the epistemic and linguistic virtues required for learning with and from each other. The pupil and the ‘preceptor’ will be co-learners and the forerunners of individuals who, in successive generations, will develop increasingly wise and comprehensive views.

In Godwin’s view, there will never be a need for a national system of pay or accreditation, but there will be a need, in the short-term, for leadership by a bourgeois educated elite. It is interesting to compare this view with Coleridge’s idea of a ‘clerisy’, a permanent national intellectual elite, most fully developed by Coleridge in On the Constitution of the Church and State (1830). The term ‘clerisy’ refers to a state-sponsored group of intellectual and learned individuals who would diffuse indispensable knowledge to the nation, whose role would be to humanize, cultivate, and unify. Where Godwin anticipates an erosion of differences of rank and an equitable education for all, Coleridge wants education for the labouring classes to be limited, prudentially, to religion and civility, with a more extensive liberal education for the higher classes. The clerisy is a secular clergy, holding the balance between agricultural and landed interests on the one hand, and mercantile and professional interests on the other. Sages and scholars in the frontline of the physical and moral sciences would serve also as the instructors of a larger group whose role would be to disseminate knowledge and culture to every ‘parish’. Coleridge discussed the idea with Godwin, but very little in it could appeal to a philosopher who anticipated a withering away of the national state; nor could Godwin have agreed with the idea of a permanent intellectual class accredited and paid by the state, or with the idea of a society that depended for its unity on a permanently maintained intelligentsia. Coleridge’s idea put limits on the learning of the majority and denied them the freedom, and the capacity, to pursue their own enquiries and opinions—as did the national education system that developed in Britain in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Godwin’s educational ideas have had little direct impact. They were not as well-known as those of Rousseau to later progressivist educational theorists and practitioners. He had, perhaps, an over-intellectualised conception of children’s development, and too utopian a vision of the kind of society in which his educational ideas could flourish. Nevertheless, it is interesting that his emphasis on autonomous thinking and critical discussion, on equality and justice in the distribution of knowledge and understanding, and his awareness of how powerful interests and dominant ideologies are insinuated through education, are among the key themes of modern educational discourse. The way in which his ideas about education are completely integral to his anarchist political philosophy is one reason why he deserves attention from philosophers of education, as well as from political theorists.

4. Godwin’s Philosophical Anarchism

a. Introduction

Godwin was the first to argue for anarchism from first principles. The examination of his ideas about education has introduced important aspects of his anarchism, including the preference for local community-based practices, rather than any national systems or institutions. His anarchism is both individualistic and socially oriented. He believes that the development of private judgment enables an improved access to truth, and truth enables progression towards a just society. Monarchical and aristocratic modes of government, together with any form of authority based on social rank or religion, are inconsistent with the development of private judgment. Godwin’s libertarianism in respect of freedom of thought and expression deserves recognition, but his commitment to sincerity and candour, to speech that presumes to assert as true only what is epistemically sound, means that not all speech is epistemically responsible. Nor is all listening responsible: free speech, like persuasive argument, requires a fair-minded and tolerant reception. To prepare individuals and society for the responsible exercise of freedom of thought and expression is a task for education.

Godwin was a philosophical anarchist. He did not specify ways in which like-minded people should organise or build a mass movement. Even in the 1790s, when the enthusiasm for the French Revolution was at its height, he was cautious about precipitating unrest. With regard to the practical politics of his day, he was a liberal Whig, never a revolutionary. But the final two Books of Political Justice take Godwin’s anarchism forward with arguments concerning crime and punishment (Book VII) and property (Book VIII). It is here that some of his most striking ideas are to be found, and where he engages with practical policy issues as well as with philosophical principles.

b. Punishment

Godwin sees punishment as inhumane and cruel. In keeping with his necessitarianism, he cannot accept that criminals make a genuinely free choice to commit a crime: ‘the assassin cannot help the murder he commits any more than the dagger’ (PJ II: 324; Bk VII, i). Human beings are not born into sin, but neither are they born virtuous. Crime is caused environmentally, by social circumstances, by ignorance, inequality, oppression. When the wealthy acknowledge this, they will recognise that if their circumstances and those of the poor were reversed, so, too, would be their crimes. Therefore, Godwin rejects the notions of desert and retributive justice. Only the future benefit that might result from punishment matters, and he finds no evidence that suffering is ever beneficial. Laws, like all prescriptions and prohibitions, condemn the mind to imbecility, alienating it from truth, inviting insincerity when obedience is coerced. Laws, and all the legal and penal apparatus of states, weaken us morally and intellectually by causing us to defer to authority and to ignore our responsibilities.

Godwin considers various potential justifications of punishment. It cannot be justified by the future deterrent effect on the same offender, for a mere suspicion of criminal conduct would justify it. It cannot be justified by its reformative effect, for patient persuasion would be more genuinely effective. It cannot be justified by its deterrent effect on non-offenders, for then the greatest possible suffering would be justified because that would have the greatest deterrent effect. Any argument for proportionality would be absurd because how can that be determined when there are so many variables of motivation, intention, provocation, harm done? Laws and penal sentences are too inflexible to produce justice. Prisons are seminaries of vice, and hard labour, like slavery of any kind, is evil. Only for the purposes of temporary restraint should people ever be deprived of their liberty. A radical alternative to punishment is required.

The development of individuals’ capacities for reason and judgment will be accompanied by a gradual emancipation from law and punishment. The community will apply its new spirit of independence to advance the general good. Simpler, more humane and just practices will emerge. The development of private judgment will enable finer distinctions, and better understanding, to move society towards genuine justice. When people trust themselves and their communities to shoulder responsibility as individuals, they will learn to be ‘as perspicacious in distinguishing, as they are now indiscriminate in confounding, the merit of actions and characters’ (PJ II: 412; Bk VI, viii).

c. Property

Property, Godwin argues, is responsible for oppression, servility, fraud, malice, revenge, fear, selfishness, and suspicion. The abolition—or, at least, transformation—of property will be a key achievement of a just society. If I have a superfluity of loaves and one loaf would save a starving neighbour’s life, to whom does that loaf justly belong? Equity is determined by benefit or utility: ‘Every man has a right to that, the exclusive possession of which being awarded to him, a greater sum of benefit or pleasure will result, than could have arisen from its being otherwise appropriated’ (PJ II:423; Bk VIII, i).

It is not just a question of subsistence, but of all indispensable means of improvement and happiness. It includes the distribution of education, skills, and knowledge. The poor are kept in ignorance while the rich are honoured and rewarded for being acquisitive, dissipated, and indolent. Leisure would be more evenly distributed if the rich man’s superfluities were removed, and this would allow more time for intellectual improvement. Godwin’s response to the objection that a superfluity of property generates excellence—culture, industry, employment, decoration, arts—is that all these would increase if leisure and intellectual cultivation were evenly distributed. Free from oppression and drudgery, people would discover new pleasures and capacities. They will see the benefit of their own exertions to the general good ‘and all will be animated by the example of all’ (PJ II: 488; Bk VIII, iv).

Godwin addresses another objection to his egalitarianism in relation to property: the impossibility of its being rendered permanent: we might see equality as desirable but lack the capacity to sustain it; human nature will always reassert itself. To this Godwin’s response is that equality can be sustained if the members of the community are sufficiently convinced that it is just and that it generates happiness. Only the current ‘infestation of mind’ could see inequality dissolve, happiness increase, and be willing to sacrifice that. In time people will grow less vulnerable to greed, flattery, fame, power, and more attracted to simplicity, frugality, and truth.

But if we choose to receive no more than our just share, why should we impose this restriction on others, why should we impose on their moral independence? Godwin replies that moral error needs to be censured frankly and contested by argument and persuasion, but we should govern ourselves ‘through no medium but that of inclination and conviction’ (PJ II, 497; Bk VIII, vi). If a conflict between the principle of equality and the principle of independent judgment appears, priority should go with the latter. The proper way to respect other people’s independence of mind is to engage them in discussion and seek to persuade them. Conversation remains, for Godwin, the most fertile source of improvement. If people trust their own opinions and resist all challenges to it, they are serving the community because the worst possible state of affairs would be a clockwork uniformity of opinion. This is why education should not seek to cast the minds of children in a particular mould.

In a society built on anarchist principles, property will no longer provide an excuse for the exploitation of other people’s time and labour; but it will still exist to the extent that each person retains items required for their welfare and day-to-day subsistence. They should not be selfish or jealous of them. If two people dispute an item, Godwin writes, let justice, not law, decide between them. All will serve on temporary juries for resolving disputes or agreeing on practices, and all will have the capacity to do so without fear or favour.

d. Response to Malthus

The final objection to his egalitarian strictures on property in Political Justice is the chapter ‘Of the objection to this system from the principle of population’ (Book VIII: vii). The objection raises the possibility that an egalitarian world might become too populous to sustain human life. Godwin argues that if this were to threaten human existence, people would develop the strength of mind to overcome the urge to propagate. Combined with the banishment of disease and increased longevity—even perhaps the achievement of immortality—the nature of the world’s population would change. Long life, extended education, a progressive improvement in concentration, a reduced need for sleep, and other advances, would result in a rapid increase in wisdom and benevolence. People would find ways to keep the world’s population at a sustainable level.

This chapter, together with the essay ‘Of Avarice and Profusion’ (The Enquirer, 1797), contributed to Thomas Malthus’ decision to write An Essay on the Principle of Population, first published in 1798. He argued that Godwin was too optimistic about social progress. They met and discussed the question amicably, and a response was included in Godwin’s Reply to Dr Parr, but his major response, Of Population, was not published until 1820, by which time Malthus’s Essay was into its fifth, greatly expanded, edition. Godwin argues against Malthus’s geometrical ratio for population increase and his arithmetical ratio for the increase in food production, drawing where possible on international census figures. He looks to mechanisation, to the untapped resources of the sea, to an increase in crop cultivation rather than meat production, and to chemistry’s potential for producing new foodstuffs. With regard to sexual passions, he repeats his opinion from Political Justice that men and women are capable of immense powers of restraint, and with regard to the Poor Laws, which Malthus wished to abolish, he argued that they were better for the poor than no support at all. Where Malthus argued for lower wages for the poor, Godwin argued for higher pay, to redistribute wealth and stimulate the economy.

When Malthus read Of Population, he rather sourly called it ‘the poorest and most old-womanish performance to have fallen from a writer of note’. The work shows that Godwin remained positive about the capacity of humankind to overcome misery and to achieve individual and social improvement. He knew that if Malthus was right, hopes for radical social progress, and even short-term relief for the poor and oppressed, were futile.

5. Godwin’s Fiction

a. Caleb Williams (1794)