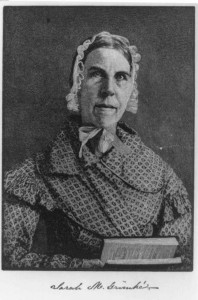

Sarah Grimké (1792—1873) and Angelina Grimké Weld (1805—1879)

Sarah Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld, sisters from a South Carolina slave-holding family, were active abolitionist public speakers and pioneer women’s rights advocates in a time when American women rarely occupied the public stage. Their personal stories about the horrors of slavery made them effective agents in the Northern abolitionist movement, and their subsequent marginalization in the leadership of that movement spurred them toward an articulation of women’s rights and duties in the public arena.

Sarah Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld, sisters from a South Carolina slave-holding family, were active abolitionist public speakers and pioneer women’s rights advocates in a time when American women rarely occupied the public stage. Their personal stories about the horrors of slavery made them effective agents in the Northern abolitionist movement, and their subsequent marginalization in the leadership of that movement spurred them toward an articulation of women’s rights and duties in the public arena.

By necessity and conviction, both sisters connected appeals for abolition of slavery with defenses of a woman’s right to political action, understanding that they could not be effective against slavery while they did not have a public voice. They are most often referenced together in historical and philosophical texts because they lived and worked together most of their lives, jointly developing their arguments and reading each other’s works. Angelina is best known for her original work in opposition to slavery and her brilliant oratory style, while Sarah Grimké developed a radical theory of women’s rights that pre-dated and influenced the beginning of the women’s right movement in Seneca Falls. Both women connected the oppression of African Americans with the oppression of women.

Table of Contents

1. Biography

a. Cultural and Formative Influences

Sarah Grimké was the sixth child born to John and Mary Grimke, plantation owners and slave holders in Charleston, South Carolina. Her father was a well-known attorney who became the chief judge of the Supreme Court of South Carolina. Sarah loved learning and studied with her older brother, hoping to go on to college and practice law like her brother, but her father forbade her from continuing her studies. At age 13, she was allowed to become the godmother of her baby sister Angelina, and was very much a part of her sister’s upbringing. In her mid-twenties, Sarah traveled with her seriously ill father to Philadelphia to be treated by a doctor, where they took up residence at a Quaker boarding house. When the treatment failed, she alone took care of him at the New Jersey seashore for the months he was dying.

Sarah and Angelina Grimké lived in an era of religious revivalism and utopian experimentalism, both of which had an impact in various times on their lives. While returning to Charleston after her father’s death, Sarah experienced a religious conversion after reading Quaker literature and began having religious mystical experiences. In 1821, at the age of 29, disillusioned with life in Charleston, Sarah moved to Philadelphia and joined the Fourth and Arch Street Meeting of the Society of Friends. Women were welcomed into the ministry in Quaker congregations; she saw the example of Lucretia Mott in the ministry in her own meeting. Sarah felt called to a role in the ministry, but her testimony in the meetings was never supported by the Quaker elders. Her conviction of a religious calling may be the reason she turned down a marriage proposal, and is evident in her early tendency to defend women’s rights using Christian theology iconography (Lerner 1998b, 4).

When Angelina Grimké came to realize the horrors of slavery, she first spoke out against it in the Presbyterian Church in Charleston where she had been an active member and teacher. She became frustrated with the Presbyterian minister who spoke privately with her against slavery but would not publicly denounce it. In 1827, Angelina, like her sister, had a religious conversion experience when Quaker minister Anna Braithwaite came to Charleston and stayed with the Grimké family. Following that event, she began worshipping in the tiny Charleston Quaker meeting. Instead of leaving Charleston, Angelina stayed on with a perceived mission to convert her family, if not to Quakerism, at least to abandon slavery. Six months of articulate and forceful discussion, intense prayer sessions, family upheavals and visits from friends and clergy did not change Angelina’s mind, nor did her arguments produce any resulting change among her family or friends. She was called to testify to Presbyterian Church leaders about her beliefs which resulted in expulsion from the church. In 1829 Angelina left South Carolina to join Sarah in Philadelphia, and began worshipping with the Fourth and Arch Street Meeting.

As women, Sarah and Angelina were sheltered and limited in both thought and action in their South Carolina culture, but joining the Society of Friends also limited their interaction with their contemporary world. In Philadelphia the only newspaper they read was The Friend, a Quaker weekly that passed along Quaker views on issues such as women’s rights. They could have benefited from larger feminist dialogue, such as in a sympathetic reading of the work of the Englishwoman, Frances Wright, who publicly campaigned for women’s rights in the U.S. in 1828-29. It seems more probable that the sisters would have known of African American activist Maria W. Stewart, the first American woman to speak publicly against slavery in 1831-33, whose work was published by William Lloyd Garrison.

In Philadelphia, Angelina taught classes at the school that her widowed sister Anna Frost had started in order to supplement her small income. Unhappy with her teaching experience there, Angelina considered attending and possibly teaching at the prestigious Hartford Female Seminary, a school founded and run by Catherine Beecher (whose views on women’s roles Angelina would later publicly criticize). Although she was impressed and excited by the opportunities she saw at Hartford, the Quaker elders would not give her permission to move there. Instead she settled into Philadelphia Quaker life, teaching at the infant school.

b. Public Activism: 1834-1837

In 1934, after the sudden death of the man Angelina expected to marry and the death of their respected brother, Thomas, who had been Sarah’s childhood companion, the two sisters found themselves growing more uncertain of the Quaker restrictions, and began looking for new ways to be “useful.” Angelina devoured news of the abolitionists’ struggles, including the persecution they suffered in nearly every northern city where they spoke. After reading about the struggles of the abolitionists, she wrote a moving letter to Garrison, which was published without her permission in his abolitionist journal, The Liberator. This letter catapulted Angelina into the public realm, and was followed in (1836) by her Appeal to the Christian Women of the Southern States. The Appeal was written in a personal tone, addressing Southern women as friends and colleagues. When copies of it reached the Grimké sisters’ home town of Charleston, they were publicly burned by the postmaster, and Mrs. Grimké was warned that her daughters would be prevented from ever visiting Charleston again.

In 1836, Angelina and Sarah moved to New York (against the advice and without the permission of the Philadelphia Quakers) to begin work as agents for the abolitionist cause. They were the only women to attend the 19-day intensive training during the Agents’ Convention of the American Anti-Slavery Convention in November. Within weeks of the training, they began offering public talks for female anti-slavery meetings in New York. In their talks they advocated practical ways that Northerners could influence slavery regulations, but also urged their audiences to locate and root out race prejudice in their own lives and communities. According to their analysis, race prejudice in the North and the South was a major support of the slave system. They understood this from their own experience with slaves and free blacks in the North, as well as through discussions with one of their mentors, the leading abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld.

Following the Agents’ Convention, both Grimké sisters began their active political campaign for the abolitionist cause. They helped organize the New York Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women which strengthened their bonds with other women activists in the anti-slavery cause and in 1837 began touring Northern cities, giving talks to packed audiences. Their work was very successful and led to the creation of more female anti-slavery associations and thousands of signatures on anti-slavery petitions. However, in every city they visited, the fact that they were women speaking before a mixed (male and female) audience created an uproar, even among abolitionist sympathizers. Many religious leaders hotly rejected the idea that women should speak from pulpits and public stages. In mid-1837, as Angelina and Sarah were on their speaking tour, the Congregational Churches issued a “Pastoral Letter” warning their congregations of “the dangers which at present seem to threaten the female character with widespread and permanent injury” and called women to remember their “appropriate duties and influence … as clearly stated in the New Testament” (Lerner 1998a, 143).

Religious leaders were not the only ones who reacted against the sisters’ work. Catherine Beecher, whom Angelina had once hoped to study with, published a critique of their approach to abolition, specifically addressed to Angelina Grimké. In her essay Beecher advocated gradualism instead of immediate emancipation, and also called women to remember their subordinate role in society. Angelina responded in the summer of 1837, publishing Letters to Catherine Beecher, defending immediate emancipation of slaves, as well as the right and responsibility of women to participate as citizens in their society. During this same period, Sarah also began writing Letters on the Equality of the Sexes.

Their speaking tour ended in late 1837 with Angelina very ill and both sisters exhausted from their grueling traveling and lecturing schedule.

c. Continuing Influence and Later Projects

The debate over women’s participation began to split the anti-slavery movement. Even the New York Executive Committee, who trained the sisters for public speaking, was unwilling to give them official “agent” status, fearing that public energy would be diverted by the women’s right issue. In letters to the Grimké sisters, abolitionist leaders Theodore Weld and Quaker John Whittier asked them to concentrate only on the anti-slavery issue. Referencing their work on women’s rights, Whittier asked, “Is it not forgetting the great and dreadful wrongs of the slave in a selfish crusade against some paltry grievances of our own?” Angelina and Sarah responded that women needed to claim free speech and other rights in order to do the work they were called to do. “What then can woman do for the slave when she is herself under the feet of man and shamed into silence?” (Lerner 1998a, 151-2)

Instead of withdrawing from the public stage, Angelina and Sarah went on to achieve even more notoriety when, in 1838, Angelina testified at a Committee of the Legislature of the State of Massachusetts, becoming the first American woman to testify in a legislative meeting. Later in 1838, at the age of 33, Angelina married abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld, and they moved with Sarah to Fort Lee, New Jersey. Although it was both Angelina’s and Sarah’s intention to continue their public activism, the pressures of running a household and raising three children, as well as the results of increasing poverty required them to withdraw from the speaking in the public arena. They continued to write and work to support abolitionist causes. One of their first projects after the marriage was to comb through back issues of Southern newspapers to gather empirical data about slavery for Weld’s book, American Slavery As It Is (1839). That text also contains essays written by the Grimké sisters which provide clear and horrifying details of the conditions of slavery from their own experiences.

Although the Grimké sisters were no longer public lecturers, the fervor they raised about the “woman question” continued to cause dissention in the abolitionist movement. That issue, joined with other divisions about utopian/anarchist withdrawal versus political action, caused the movement to split into two separate organizations in 1840. Unfortunately the organization which embraced political action – in some ways the natural choice for Weld and for the Grimké sisters – also excluded the participation of women. Weld and both of the sisters withdrew from active participation for a short time; when Theodore resumed his activist work in 1841, Angelina and Sarah were overwhelmed with caring for the young children and maintaining the farm.

In 1848, Weld and the two sisters established a co-educational boarding school out of their home, with Angelina teaching history and Sarah teaching French. Although friends and family sent their children there (two sons of Elizabeth Cady Stanton attended) the school was a struggle, and made very little money. In 1854 the Welds and Sarah joined the utopian community Raritan Bay Union, where Theodore Weld started the progressive and experiential Eagleswood School. Angelina and Sarah both taught and assisted with administration. The school continued when the Union failed two years later, with Angelina and Sarah as teachers. In 1862 the family moved to Boston to continue their teaching careers.

Angelina and Sarah remained committed to women’s issues, but their ability to be physically involved in activism was limited. Their example as women who spoke publicly against slavery and for women’s rights continued to inspire other female activists. Recognizing Angelina’s impact on women’s rights, the women’s rights leaders elected her a member of the Central Committee of the 1850 woman’s rights convention even though she was unable to attend. Both women continued to participate in future women’s rights convention and in the women’s movement, however mostly through letters and other writings. As late as 1870 they were both vice presidents of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association, and symbolically cast ballots in a local election.

In 1868, Angelina and Sarah discovered that their brother Henry had fathered children by his female slave, Nancy Weston. Those children, Archibald, John and Francis James Grimké had been sold into slavery by their half-brother. When Angelina and Sarah found out about these three young men, they established close relationships, and supported Archibald and Francis through college and graduate school. Archie studied law at Harvard, and Francis went to Princeton Theological Seminary. Both men went on to national leadership among the Black communities. As pastor of the 15th Street Presbyterian Church in Washington D.C., Francis Grimké and his wife Charlotte Forten Grimké were friends and colleagues of Anna Julia Cooper. Archibald was a vice-president of the NAACP and president of the American Negro Academy.

Sarah Grimké died in 1873, Angelina Grimké Weld died in 1879. Catherine Birney, a former student at their boarding school, published a full biography of the sisters in 1885.

2. Philosophical Writing

a. Abolitionist Reasoning

Although their early education was limited, while growing up in a family of lawyers and judges the Grimké sisters became familiar with constitutional law based on the liberal political theory of the founders of the constitution. According to historian Gerda Lerner (1998b, 22) Sarah had read Locke, Jefferson, and other Enlightenment thinkers, and her writing consistently integrates these Enlightenment ideals with Biblical analysis. In Sarah’s first major writing, An Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States (1836), she combines a scholarly interpretation of the Old Testament with language from Bill of Rights. It is written in the style of the apostolic letters in the New Testament, and as such seems odd to modern ears. In this essay, Sarah’s first claim is that slavery is in opposition to Biblical teaching. She uses Genesis to support her claim that although humans can use animals as “means” – as food to sustain their existence, all people are created in God’s image and so cannot be used as mere means for others’ ends. She moves to a more Kantian understanding that making such a God-created “man” into a “thing” violates “God’s unchanging degree.” Given a philosophic understanding that immortality is dependent on rationality, she points out that every slave is a “rational and immortal being” and so has certain “inalienable rights” (Ceplair 92), reflective of her reading of Locke’s Natural Rights argument. In her Epistle, Sarah called “every Christian minister” to “preach the word of immediate emancipation” (Ceplair 109).

In 1836, Angelina published her first work, the Appeal to the Christian Women of the South, written in the form of a letter to close friends. Her claim for the equality of slaves is also based on natural rights as well as God-given rights. In the Lockean language of the Declaration of Independence she points out that “all men, every where and of every color are born equal and have an inalienable right to liberty” (Ceplair 38). She continues by dismantling claims that slavery is sanctioned under Hebrew law, pointing out that none of the ways that Hebrew men or women became servants in Old Testament law are applicable to the conditions of African American slavery. Responding to slave-owners’ claims that Christ did not condemn slavery, she demonstrates how treating other humans as “chattel property” contradicts the commandment that “Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them” (Ceplair 50). While acknowledging that women do not have the right to vote, she evokes the image of Esther’s political action in the Bible, appealing directly to Southern women to gather signatures on petitions to their legislatures. “Such appeals to your legislatures would be irresistible, for there is something in the heart of man which will bend under moral suasion” (Ceplair 66).

After reading Angelina’s Appeal to the Christian Women of the South, influential educator Catherine Beecher (1800-1878) responded by publishing an 1837 article addressed to Angelina Grimké, titled An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism with reference to the Duty of American Females, critiquing the idea of immediate emancipation. Beecher was one of a number of Americans who agreed that slavery was wrong but argued for “gradualism.” Gradualists argued that slavery could be eradicated slowly though such measures as stopping the slave trade, freeing the children of slaves, banning slavery in new territories, or even re-colonizing slaves back to Africa. Beecher supported the re-colonization movement which raised funds to send black ex-slaves back to Africa. Responding in the Letters to Catherine Beecher, Angelina defended immediate abolition, showed the fallacies of gradualism, attacked racial prejudice, and defended women’s right and responsibility to do public activism. She reiterated the abolitionist principle “that no circumstances can ever justify a man holding his fellow man as property,” concluding that the slave owner is “bound immediately to cease holding (the slave)” (Ceplair 149-150). She also pointed out that although Northerners had outlawed slavery, they were guilty of racial prejudice, which was at the heart of gradualism and the re-colonization movement. And so, she said, “I am trying to talk down, and write down and live down this horrible prejudice … we must dig up this weed by the roots out of each of our hearts…” (Lerner 1998a, 141). Later in 1837, responding to a public request to present “definite practicable means” by which Northerners could have affect on slavery, the Grimké sisters once again point to racial prejudice in the North as also responsible for making slavery possible. As she reiterated later, “Northern prejudice against color is grinding the colored man to the dust in our free states, and this is strengthening the hands of the oppressor continually” (“Letter to Clarkston” Ceplair 121). The Grimkés understood that slavery and race inequity “degrades the oppressor as well as the oppressed” (Weld, et al 1934, 790).

b. Women’s Rights

In order to claim the right to speak in public, Angelina and Sarah had to argue against the conventional philosophy that men and women were naturally meant to occupy “separate spheres” of existence – that woman’s role was in the private sphere, while men controlled the public sphere. As has often been the case in history, some of the most fervent opposition to women’s rights came from other women. Catherine Beecher was well-known as a pioneering advocate for women’s education, who established many schools for women including the Hartford Female Seminary. As such, she was a public person by virtue of the organizations that she created, and the leadership roles she played in society, yet she did not believe that women should have political roles. Although Beecher argued that child-raising and women’s work in the household required that women be educated, she did not support women’s suffrage or the idea of women petitioning Congress. As she said, “Men are the proper persons to make appeals to the rulers whom they appoint… [women] are surely out of place in attempting to do it themselves” (Lerner 1998a, 140).

In Letters XI and XII of her response to Beecher, Angelina logically dismantles the separate spheres mentality as prescribed by Rousseau and claimed instead that as moral beings the spheres of woman and man are the same. She explicitly connects abolitionist work to women’s rights, noting that her “investigation into the rights of the slave has led me to a better understanding of my own.” The natural corollary of her abolitionist argument that as slaves, “human beings have rights because they are moral beings” is that women too have human rights that are not dependent on their sex. Hence, “whatever is morally right for a man to do, it is morally right for a woman to do” (Ceplair 194-5). Angelina ends these two letters with the recommendation that the reader refer to Sarah Grimké’s writing on the subject of women’s rights.

Immersed as they were in Christian culture and traditions, the Grimké sisters faced Bible-based opposition to the idea of women’s equality. Given their religious training, they replied to their critics with careful Biblical reasoning in defense of women’s rights, against what they said was the common “perverted interpretation” of the Bible. In the first chapter of Sarah’s Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women (Ceplair 104) she begins with the two creation stories in Genesis to claim women’s equality. First, she points out that women as well as men were created in God’s image, in “perfect equality.” In the second creation story, Eve is formed out a rib of Adam, to be a helpmeet, “in all respects his equal,” as she reasons that a companion created by God would necessarily be his equal. Her religious critics would then point to the story of the fall, and Eve’s role in that. Sarah points out that Eve succumbed to supernatural evil, while Adam succumbed to merely mortal temptation, and thus men could not claim moral superiority over women. She claims that the phrase “Thou wilt be subject unto thy husband, and he will rule over thee” is a mistranslation. The Hebrew, she claimed, “uses the same word to express shall and will.” Thus, the phrase should in fact be translated as a prophecy, not a command, in the same way that the “immediate struggle for dominion” among humans is a prophecy, not a command. She concludes that there is no reason to conclude from the Genesis story that original sin created a necessary condition of inequality between men and women. Then, as God has not caused a condition of inequality between men and women, she asks in the next letter that her brethren “take their feet from off our necks allowing us to stand upright” (Ceplair 208).

Angelina and Sarah continued throughout their work to claim their rights as citizens of the republic, whose “honor, happiness and well-being are bound up in its politics, government and law” (Lerner 1998a, 8). This claim was echoed 10 years later in 1848 in the Declaration of Sentiments presented at Seneca Falls Convention for women’s rights. Throughout Sarah’s and Angelina’s writing, their arguments for women’s rights is based on the moral authority of the reasoning person – similar to the arguments that they both made for natural rights for African Americans. In this they may also be reflecting some of the arguments that they had read in Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 Vindication of the Rights of Women.

c. Connecting Race Oppression to the Oppression of Women

The Grimké sisters were among the first to explicitly connect race oppression to women’s oppression. Sarah “thanked” John Quincy Adams in her Letters on Equality for placing women “side by side with the slave” “ranking us with the oppressed.” Using a Kantian ethical argument that opposes using humans as means rather than as ends in themselves, she noted that historically “woman has … been made a means to promote the welfare of man” (Ceplair 209). She tied the subordination of slaves and women to educational deprivation, noting that both women and slaves been deemed mentally inferior “while being denied the privileges of liberal education” (Lerner 1998a, 122-3). In 1863 after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Angelina said that as women, “True, we have not felt the slaveholder’s lash; true we have not had our hands manacled, but our hearts have been crushed … I want to be identified with the negro; until he gets his rights, we shall never have ours” (Lerner 1998a, 263). Throughout their lives the sisters also stressed their bonds of sisterhood with African American women, in both their writing and in their close friendships with African American women.

Sarah’s claim that sexual oppression was a major cause of the subordination of women was far ahead of her contemporaries. Writing in the late 1850s Sarah used the language of bondage to speak of women’s roles. “She is your slave, the victim of your passions, the sharer willingly and unwillingly of your licentiousness” (Lerner 1998b, 81). She examined marital rape in her essay “Marriage” in an era when it would have been shocking for a woman to discuss such things. She identifies women as in a position of slavery for being unable to refuse sex to her husband. Instead of having loving sexual relations, women would often “rise in the morning oppressed with a sense of degradation from the fact that their chastity has been violated…” discovering that she is a “legal prostitute … a mere convenience” (Lerner 1998b, 113-114). She called for the right of education for women, full human rights, financial independence and a woman’s right to decide when and if she would become a mother. In other essays she identified men, individually and as a group, as having benefited from women’s oppression in the same way that plantation owners benefited from race oppression.

When John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women came out in 1869, Sarah at age 77 walked throughout her neighborhood selling 150 copies of the book to her neighbors (Lerner 40). It’s no wonder that Mill’s book appealed to Sarah – it contains arguments for equal rights for women that are very similar to those developed by the Grimké sisters.

3. References and Further Reading

- Bartlett, Elizabeth Ann (ed.) 1988. Sarah Grimké, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and other Essays. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- In this collection of the writings of Sarah Grimké Bartlett argues that Sarah’s Letters is the first philosophical work on the condition of women in America.

- Birney, Catherine. 1885. The Grimké Sisters: Sarah and Angelina Grimké: the First Women Advocates of Abolition and Women’s Rights. Boston: Lee and Sheppard.

- The earliest biography of the Grimké sisters written by the daughter of a family friend. The full text is available in e-format from several online publishers.

- Ceplair, Larry, (ed). 1989. The Public Years of Sarah and Angelina Grimké: Selected Writings 1836-1839. New York: Columbia University Press.

- This valuable text contains the major works of the Grimké sisters (some of them excerpted) with short introductions by the editor.

- Grimké, Angelina. 2003. Walking by Faith: The Diary of Angelina Grimke, 1828-1835. Ed. Charles Wilbanks. University of South Carolina Press.

- Lerner, Gerda. 1998a. The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reprint of Lerner’s 1967 biography with a new introduction; this is the most complete intellectual biography of the Grimké sisters.

- Lerner, Gerda. 1998b. The Feminist Thought of Sarah Grimké. New York: Oxford University Press. This companion book to Lerner’s full biography contains a short biographical introduction to Sarah Grimké’s life, as well as reprints of Sarah’s letters and essays.

- Lumpkin, Katharine Du Pre. 1974. The Emancipation of Angelina Grimké. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Biography of Angelina Grimké that explores the forces behind Angelina’s break with the Southern Christian culture of her youth.

- Weld, Theodore Dwight, ed. 1839. American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society.

- Weld, Theodore Dwight, ed. 1934. Angelina Grimké Weld, and Sarah Grimké. Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah Grimké: 1822-1844. 2 vols. Gilbert H. Barnes and Dwight L. Dumond, eds. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc.

Author Information

Judy Whipps

Email: whippsj@gvsu.edu

Grand Valley State University

U. S. A.