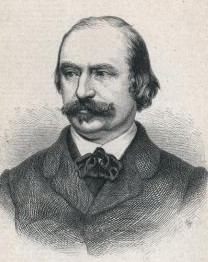

Eduard Hanslick (1825–1904)

Eduard Hanslick was a Prague-born Austrian aesthetic theorist, music critic, and the first professor of aesthetics and history of music at the University of Vienna, who is commonly considered the founder of musical formalism in aesthetics. His seminal treatise Vom Musikalisch-Schönen (On the Musically Beautiful) of 1854 is one of the most significant contributions to musical aesthetics ever written, as is evident from the ten editions the book went through during Hanslick’s lifetime, with many editions to follow. Hanslick’s classic treatise has been translated into English as early as 1891. On the Musically Beautiful, or OMB, posits an aesthetic approach to music derived solely from its specific material features that helped to shape the fields of aesthetics and musicology up to our own day. Hanslick’s scientific and objectivist orientation, his critical attitude towards metaphysics, and his theory of emotion—strikingly reminiscent of modern cognitive concepts—guarantee his continued relevance for current debates.

Eduard Hanslick was a Prague-born Austrian aesthetic theorist, music critic, and the first professor of aesthetics and history of music at the University of Vienna, who is commonly considered the founder of musical formalism in aesthetics. His seminal treatise Vom Musikalisch-Schönen (On the Musically Beautiful) of 1854 is one of the most significant contributions to musical aesthetics ever written, as is evident from the ten editions the book went through during Hanslick’s lifetime, with many editions to follow. Hanslick’s classic treatise has been translated into English as early as 1891. On the Musically Beautiful, or OMB, posits an aesthetic approach to music derived solely from its specific material features that helped to shape the fields of aesthetics and musicology up to our own day. Hanslick’s scientific and objectivist orientation, his critical attitude towards metaphysics, and his theory of emotion—strikingly reminiscent of modern cognitive concepts—guarantee his continued relevance for current debates.

OMB is notorious primarily for its ostensible repudiation of any pertinent connection between music and affect states. Hanslick’s concept of music, according to this view, is based solely on the formal aspects of pure music that does not arouse, express, represent, or allude to human emotion in any way relevant to its artistic essence: The content of music, Hanslick (in)famously proclaimed, consists entirely of “sonically moved forms.”

This article provides an introduction to Hanslick’s biography, his early music reviews, which differ considerably from the eventual opinions he is commonly associated with, and portrays the key arguments of Hanslick’s aesthetic approach as presented in OMB, including a reconstruction of the complex genesis of this book. The concluding paragraphs encompass an overview of several crucial sources of Hanslick’s viewpoint, seemingly oscillating between German idealism and Austrian positivism, as well as a concise history of Hanslick’s reception in analytical philosophy of music, which continues to struggle with the issues posed by Hanslick’s cognitive concept of emotion and has drafted numerous strategies to circumvent Hanslick’s skeptical outcome.

Table of Contents

- Biography

- Early Works and Critical Writings

- Vom Musikalisch-Schönen / On the Musically Beautiful

- Genesis and Conceptual Organization of OMB

- Purpose, Methods, and General Outlook of OMB

- Arousal, Expression, and the Cognitive Concept of Emotion

- The Musically Beautiful and Music’s Relation to History

- Listening, Music’s Relation to Nature, and Music’s Content

- Conclusion: The Curious Nature of Hanslick’s Formalism

- The Intellectual Background of Hanslick’s Aesthetics

- The Reception of Hanslick’s Aesthetics and Its Relevance to Current Discourse

- References and Further Reading

1. Biography

Eduard Hanslick, who Germanized his surname by inserting a “c” upon his move to Vienna in 1846, was born in Prague on September 11, 1825 as the son of Josef Adolf (1785–1859) and Karoline Hanslik (1796–1843), daughter of the Jewish court factor Salomon Abraham Kisch (1768–1840). According to Hanslick’s memoirs, his father was responsible for his education and thus may have sparked his interest in aesthetics, as Josef Adolf edited the two volumes of Johann Heinrich Dambeck’s Vorlesungen über Ästhetik (Lectures on Aesthetics, 1822–23) and filled in as Dambeck’s substitute in 1816–17, teaching aesthetics at Prague’s Charles University. Hanslick, who also took lessons with the renowned composer Václav Tomášek (1774–1850), completed his philosophical elementary studies—a three-year course in general education mandatory for all prospective university attendees—between 1840 and 1843, enrolled in law at Prague, and attained his doctoral degree in Vienna in 1849 (on Hanslick’s early days, see Grey 2002, 828–29; Grey 2011, 360–61; Hanslick 2018, xv–xvi). Hanslick’s background in law had significant influence on his philosophical methodology as his standard for evidence and his emphasis on “proximate causes” (Hanslick 1986, 32)—which limit the chain of “admissible causes-in-fact” and enable Hanslick’s strong focus on “the music itself” instead of the listener, performer, or composer (Pryer 2013, 55)—are clearly derived from juridical training. After a short-lived employment as a fiscal civil servant in Klagenfurt (Carinthia) in 1850–52, during which Hanslick prepared for an academic profession (Wilfing 2018, 91n), he returned to Vienna to work at the ministry of finances and was subsequently transferred to the ministry of education in 1854.

This move proved crucial for Hanslick’s future career, as Count Thun-Hohenstein (1811–88), who led the education department from 1849 to 1860, had been charged with the overall reform of Austrian education following the 1848–49 revolution, and Hanslick thus came into direct contact with Thun’s agenda and the demands of the science policies of the Hapsburg Monarchy. The initial traces of the book he would become famous for also fall within this time frame, with OMB completed in 1854. In 1856, this book was acknowledged retroactively as a philosophical habilitation, thereby granting Hanslick an unsalaried professorship at the University of Vienna that turned into a salaried position in 1861, and ultimately a full post in 1870. Hanslick retained this post until he retired in 1895, and his successor Guido Adler (1855–1941) was appointed as professor of theory and history of music, a designation diverging markedly from Hanslick’s emphasis on aesthetics. Hanslick was established profoundly in the cultural and musical scenery of Vienna: he consulted in awarding public music grants and judged musical contests, was an official Austrian delegate at international conferences and world fairs, and he became the first chair of Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich (Monuments of Musical Art in Austria) from 1893 to 1897, a society editing musical pieces of historic bearing on Austria until today. In addition to his academic activities, Hanslick experienced a widely successful career as a music critic (see the next section), which lasted until 1895, when Hanslick retired from his music editor post at Neue Freie Presse. Despite his retirement, Hanslick continued to publish criticism in this very journal until his death in 1904, with the last text to appear on April 7, two months before his passing—an event noted as far as the Musical Times and the New York Times (McColl 1995).

2. Early Works and Critical Writings

Except for his aesthetic treatise, Hanslick is renowned primarily for his activities as a music critic. As philosophical commentators usually concern themselves exclusively with OMB, the present section will briefly sketch Hanslick’s relevance in 19th-century musical discourse and will also indicate the diversity of his critical position. Today, Hanslick is known best for his skeptical attitude towards the New German School—a vague label for a loose group that is thought to comprise composers such as Hector Berlioz (1803–69), Franz Liszt (1811–86), and Richard Wagner (1813–83), but does also refer to influential journalists such as Franz Brendel (1811–68), editor-in-chief of Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. Hanslick’s career as a music critic started early on as an occasional contributor to Beiblätter zu Ost und West (Prague 1844) and—upon his move to Vienna in 1846—the Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, ultimately transferring to the imperial Wiener Zeitung in 1848, prior to his music editor posts at Die Presse (1855–64) and its liberal offshoot Neue Freie Presse (1864–95). At that time, Hanslick proved to be an advocate of composers he would eventually disapprove of, such as Berlioz, who was called the “most magnificent phenomenon in… musical poetry,” and Wagner, who was proclaimed the “greatest dramatic talent among living composers” (Hanslick 1993, 40, 59; for the latter review, see Hanslick 1950, 33–45). Hanslick, who was acquainted personally with important composers of his era—he met Wagner as early as 1845 and acted as a local guide for Berlioz in 1846 (Payzant 1991 and 2002, 63–71)—at that time professed a romantic outlook (Yoshida 2001, 181–84) and deemed “pure” music a “language of the emotions” and the “revelation of the innermost world of ideas” (Hanslick 1993, 98, 115). For readers of an aesthetic theorist commonly associated with the “repudiation” of emotive musical meaning (Budd 1980) and the proponent of a classicist conception of music that does not refer to anything beyond itself, Hanslick’s 1848 essay on “Censorship and Art-Criticism” must seem particularly surprising. In this text, he condemns the “inadequate perspective that saw in music merely a symmetrical succession of pleasing tones.” Truly artful music, he continues, represents “more than music”; it is a “reflection of the philosophical, religious, and political world-views” of its time (Hanslick 1993, 157).

In the early 1850s, however, Hanslick’s outlook on music shifted considerably and eventually developed into a more “formalist” viewpoint that inverted his previously positive appraisal of Wanger’s operas. Although an exact date or a conclusive inducement for his “volte-face” (Payzant 1991, 107) is hard to determine definitively, the classicist writings of the Prague music critic Bernhard Gutt (1812–49), from whom he adopted multiple quotations (Payzant 1989), the failed political upheaval of 1848–49, and the resulting execution of his cherished colleague Alfred Julius Becher (1803–48) seem to be crucial reasons for Hanslick’s change of opinion (Bonds 2014, 153–54; Landerer and Wilfing 2018, sec. 2). Whereas Hanslick regarded “pure” music as an exhaustive repository for intellectual reflection that exerts tangible impact on the world of politics and religion in 1848, he from this time on develops a more formalistic conception of musical artworks that emphasizes their essentially autonomous nature. In making this move, Hanslick took part in the general erosion of Hegelian criticism, the political direction of which lost most of its appeal in the aftermath of 1848 (Pederson 1996), and entirely detached music and its aesthetic qualities from its involvement with worldly politics. Whereas the political activities of other critics ceased while they retained crucial elements of Hegelian aesthetics, such as emotivism or its focus on concrete content, Hanslick’s reversal was virtually complete. This turn is observable particularly in respect to the debate about external musical meaning that Hanslick declared the pivotal feature of art in 1848. A few years later, prior to the initial edition of OMB in 1854, he had reversed his attitude entirely by stating that “if an orchestral composition requires external means of conceptual understanding [that is, a literary program] in order to please… then its musical value already appears to be in question” (Hanslick 1994, 293). Hanslick’s notion of music’s nature thus shifted from a romantic position emphasizing conceptual meaning to an appraisal of internal musical meaning oriented towards formal issues such as the inherent potential of the main theme or the clarity of melodic figures (Payzant 2002, 88–91, 96–98, 117–19).

Although Hanslick therefore adopted a critical attitude towards the New German School in later years and took issue with its poetization of “pure” music (Larkin 2013), certain matters have to be kept in mind that challenge the widespread assumption of Hanslick being a “stodgy, pedantic spokesperson for ‘conservative’ musical causes” (Gooley 2011, 289). Hanslick’s criticism of Wagner and his followers generally concerned the musical aspects of their works and deplored an absence of motivic-thematic manipulation or an overly rigorous devotion to a literary program that supposedly interfered with the “organic” unfolding of melody. His general valuation of these works, however, often proves to be astoundingly differentiated (on Hanslick’s appraisal of Wagner, see Grey 1995, 1–50; Pederson 2013, 176–77; Bonds 2014, 237–46). Although Hanslick assessed Der Ring des Nibelungen in 1876 to be “a distortion, a perversion of basic musical laws,” he was at the same time able to realize that Wagner’s tetralogy represents “a remarkable development in cultural history” (Hanslick 1950, 139, 129). It is beyond serious debate that Hanslick preferred Beethoven (1770–1827), Brahms (1833–97), and Mozart (1756–91) to Mahler (1860–1911), Strauss (1864–1949), or the Wagner “school.” Hanslick, however, did not panegyrize his preferred musicians as he did not condemn his “opponents” without reservation. Although Hanslick bemoaned Wagner’s musical system, his continuous modulations, and the dubious semantic qualities of the Leitmotiv—which he called “musical uniforms”—he nonetheless appreciated his “genius for theatrical effect” (Hanslick 1950, 121, 151) and stressed the musical virtues of specific sections of Wagner’s operas. As he clarified in 1889: “Only a fool or dedicated factionist” would answer the question of Wagner’s qualities “with two words: ‘I idolize him!’ or ‘I abhor him!’” (Hanslick 1889, 56). Furthermore, Hanslick critically (and sometimes financially) supported more modernistic composers such as Bedřich Smetana (1824–84) or Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) as long as their general artistic principles conformed to his aesthetic approach to a certain degree (Brodbeck 2007 and 2009; Larkin 2013).

3. Vom Musikalisch-Schönen / On the Musically Beautiful

a. Genesis and Conceptual Organization of OMB

From July 1853 to March 1854, Hanslick pre-published several chapters of OMB as stand-alone articles that deal with the subjective impression and (physiological) perception of music, as well as with the complex relations between music and nature. His three-piece essay “On the Subjective Impression of Music and its Position in Aesthetics” (Hanslick 1853) was eventually transformed into chapters 4 and 5 of the finalized manuscript, whereas “Music in its Relations to Nature” (Hanslick 1854)—itself based on a public lecture of 1851—turned into chapter 6, with both texts running through hardly any significant alterations. Scholarship on the actual genesis of OMB is rather sparse, as Hanslick’s private records were lost during the Second World War (Wilfing 2018, sec. 1), and has not yet reached a consensus regarding the chronological development of Hanslick’s momentous monograph. Whereas Geoffrey Payzant surmised that Hanslick’s articles were taken from the final version of OMB (Payzant 1985, 180), recent research points to the logical order of Hanslick’s argument that runs counter to the familiar sequence of published chapters in OMB and assumes that these three chapters (4–6) were indeed written prior to the more famous chapters 1 to 3, therefore presenting the nucleus of OMB (Landerer and Wilfing 2018, sec. 4; Hanslick 2018, xvii–xix). According to this view, Hanslick first lays the foundation for his aesthetic approach by clarifying an idea of tone (chapter 6) and the way in which tones are received from the standpoint of physiology and psychology (chapters 4 and 5). This analysis is followed by Hanslick’s concept of emotion, how emotions are predicated upon these physiological and psychological responses, and what role emotions play in musical aesthetics (chapters 1–2). Finally, following Hanslick’s hypothesis that emotion does not form a substantial component of objectivist aesthetics, he presents his positive thesis (chapter 3) and closes his argument with concluding comments that summarize his key findings and widen the conceptual framework of OMB (chapter 7).

b. Purpose, Methods, and General Outlook of OMB

Hanslick did not write any other academic works apart from OMB and the Geschichte des Concertwesens in Wien (History of Concert in Vienna, 1869) and focused his literary output almost entirely on reviews. Why did he decide to publish an aesthetic treatise at the age of 29? The reason given by Hanslick himself is to provide a critique of aesthetic emotivism that dominated mid-century discourse and to challenge the “advocates of the music of the future,” who supposedly endangered the “independent significance of music” (Hanslick 2018, lxxxv). By directly accusing Liszt and Wagner of belittling the inherent qualities of “pure” music, Hanslick contributed significantly to the view that OMB has to be read as a book directed against Wagner—a view that was conducive for the longevity of Hanslick’s treatise through the discussions surrounding the New German School. Even though there is some truth to this claim, scholars contest that Wagner’s music could be actually regarded as the prime spark for the production of OMB (Grey 2003, 169; Brodbeck 2014, 50), not least of all since Wagner’s later works that Hanslick specifically disapproved of were not yet written and Wagner’s name rarely appears in the initial edition of Hanslick’s treatise (several quotes from Wagner’s theoretical writings are belatedly included in the sixth edition of 1881). Wagner’s music—even though it was a useful target in order to remain relevant—thus does not seem to be the crucial reason for writing OMB, as the conceptual framework of Hanslick’s argument would have been very much the same “had the figure of Wagner not been there” (Bujić 1988, 8). A more tangible motive seems to be Hanslick’s very early aspiration towards an academic profession in order to leave behind his rather tedious employment as a public servant. We know from letters written around 1851 that Hanslick noticed the absence of musical aesthetics and musicology from the Viennese university curriculum and saw the opportunity to carve a niche for his unique talent. In light of Hanslick’s academic ambitions, it comes as no surprise that OMB does not start with a theoretical definition of art, music, or beauty. On the contrary, Hanslick’s examination commences with an exhaustive definition of musical aesthetics as a scientific discipline.

Whereas romantic aesthetic theorists had occupied themselves with music’s relation to affect states, feelings, and emotions, scientific aesthetics should focus on the object itself instead of its (historical) production or (arbitrary) reception. If musical aesthetics is to become scientific, Hanslick proclaims in a sentence that strikingly anticipates Edmund Husserl’s (1859–1938) phenomenology (Wilfing 2016, 24–25), it has to “approach the natural scientific method at least as far as trying to penetrate to the things themselves” (Hanslick 2018, 1). Furthermore, the specified aesthetics of music should detach itself from any theoretical dependency on a general concept of artistic beauty that is employed to categorize “pure” music ex post facto. German idealism typically contrived an aesthetic approach firmly rooted in an overarching philosophical framework. Art, regardless of the specific medium, thus must satisfy certain epistemic principles and ethical criteria derived from this general system in order to be classified as beautiful. Idealist aesthetics therefore typically identified universal conditions of artistic beauty that were binding equally for a poem, a tragedy, a painting, a sculpture, or a piece of music (Wilfing 2018, sec. 3.3). For Hanslick, this system-bound approach was completely misguided as he is concerned exclusively with musical beauty, the “musically-beautiful,” so that it is even hard to see how his notion of specific musical beauty is related to any general concept of beauty (Bonds 2014, 190). For him, the “laws of beauty of each art are inseparable from the characteristics of its material, of its technique” (Hanslick 2018, 2). For this reason alone, Payzant’s rendition of Vom Musikalisch-Schönen as On the Musically Beautiful captures Hanslick’s ideas much better than Cohen’s The Beautiful in Music that suggests an aesthetic approach contrary to Hanslick’s intentions: he did not propose an abstract principle of artistic beauty, administered retroactively to “pure” music, but was interested principally in beauty solely and explicitly manifest in the art of tones (Hamilton 2007, 81; Bonds 2014, 190).

c. Arousal, Expression, and the Cognitive Concept of Emotion

To this end, Hanslick develops two central theses: a positive one, explored in chapter 3, that attempts to show that musical beauty is dependent completely on the inherent qualities of music itself, and a negative one, defined in chapters 1–2, that challenges the familiar concept that music is supposed to represent feelings and that its emotive content forms the basis of aesthetic judgment. Both ideas share common ground in Hanslick’s objective approach: as the musical artwork and its material features represent the core of Hanslick’s aesthetics, the “subjective impression” of music, its emotive impact, is relegated to a secondary aftereffect of musical material. We must thus “stick to the rule that in aesthetic investigations primarily the beautiful object, and not the perceiving subject, is to be researched” (Hanslick 2018, 2–3). Hanslick specifically addresses two ways in which music is thought to be related to affect states: (1) The idea that music’s purpose is to arouse emotion and (2) that emotions represent the content of musical artworks (an assumption employed frequently to compensate for the lack of notional meaning in music alone). The first stance is countered by the classical argument of beauty having no purpose and “content of its own other than itself.” Beauty may very well arouse pleasant feelings in the perceiving individual, but to do so is not at all constitutive for the musically beautiful that exists apart from the listener’s cognition and remains beautiful “even if it is neither viewed nor contemplated. The beautiful is thus namely merely for the pleasure of the viewing subject, but not by means of the subject” (Hanslick 2018, 4). In an argument that anticipates Edmund Gurney’s (1847–88) renowned distinction between impressive music and expressive music (Gurney 1880, 314), Hanslick moreover maintains that music’s beauty and its emotive impact do not correlate inevitably. Thus, a beautiful composition may not arouse any specific feelings, whilst the strong emotive impact of another musical piece does not necessarily substantiate its aesthetic qualities (Hanslick 2018, 31–33; Robert Yanal 2006 dubs this idea the “third thesis” of OMB). In general, emotive arousal—for the most part depending on individual experience, musical edification, historical discourse, and so on—cannot provide a reasonable foundation for scientific aesthetics as it exhibits “neither the necessity nor the exclusivity nor the consistency” required to establish an aesthetic principle (Hanslick 2018, 9).

In chapter 2 of OMB, Hanslick presents his key argument against emotion forming the content of “pure” music by introducing his cognitive concept of emotion—a concept that brought his treatise to the forefront of analytical aesthetics. There was widespread consensus amongst idealist systems of art that art must have some sort of content. As “pure” music lacks tangible meaning, romantic theorists invoked the opposite of conceptual definiteness as the obvious candidate for music’s content: emotion (love, fear, anger, and the like). This claim, Hanslick maintains, represents the weak spot of musical emotivism. Emotion by no means forms the conceptless counterpart to literary meaning. On the contrary, emotions are “dependent on physiological and pathological conditions” and are invoked by “mental images, judgments, in short by the entire range of intelligible and rational thought” (Hanslick 2018, 15). The analytical philosopher Peter Kivy (1990, chap. 8) popularized this view with a practical example: If I assume that uncle Charlie is cheating during a card game, the anger I experience is contingent on the object of my emotion, Charlie. However, in order to be angry, a complex structure of cognitive parameters has to be in place. I must consider cheating an immoral or indecent behavior—a belief built upon some sort of ethical system—that is performed purposely by Charlie. As soon as I spot that Charlie is not deceitful wittingly and has played the wrong cards by accident, my anger is likely to evaporate, as its conceptual foundation disappears. Emotion, in short, needs an intentional object to be an emotion—an object that “pure” music is unable to provide. As music lacks the “cognitive mechanism” necessary to portray the objects of concrete emotions, the depiction of a specific feeling “does not at all lie within music’s own capabilities” (Hanslick 2018, 15–16). However, music alone can express the dynamic features of emotions via its own musical impetus and is thus able to portray “one aspect of feeling, not feeling itself” (Hanslick 2018, 18). Thus, even though music alone cannot express love, fear, or anger in a direct manner, its dynamic structure can reproduce the associated movement of concrete emotions or actual events (Hanslick 2018, 30), but not in ways that allow for definite meaning, as the dynamic character of love or anger could both be violent, desperate, or passionate in specific instances.

Hanslick’s exact stance on the relation of emotion and “pure” music represents a major point of contention in current research. Several scholars hold that Hanslick severed any relevant bonds between music and affect states, so that music itself “has nothing to do with emotion” (Zangwill 2004, 29) and emotions in turn have “nothing to do with musical beauty” (Lippman 1992, 299). Other scholars point to the preface of Hanslick’s treatise, in which he states that for him the value of beauty is based on “the direct evidence of feeling” and that his protest only pertains to the “mistaken intrusion of feelings in the domain of science” (Hanslick 2018, lxxxiv). In chapter 1, Hanslick makes the same move when it comes to musical arousal: he does not want to “underestimate” the “strong feelings that music awakens from their slumber,” but merely refutes the “unscientific assessment of these facts for aesthetic principles” (Hanslick 2018, 9). For Payzant, Hanslick accepts music’s capacity to arouse, express, or portray emotion; he only “says that to do so is not the defining purpose of music” (Hanslick 1986, xvi). Stephen Davies and Peter Kivy, who in 1980 concurrently established a concept of musical emotion based chiefly on the dynamic features of musical structure that readily suggest the outward features of expressive behavior (Trivedi 2011), regarded Hanslick as a historical precursor to their shared model of enhanced formalism. The crucial disparity between enhanced formalism and Hanslick’s aesthetics, both authors hold, is that they conceive of expressive properties as objective musical properties, whereas Hanslick was reluctant to take this step (Davies 1994, 204; Kivy 2009, 64). Based on numerous passages of OMB that suggest music’s ability to be “itself intellectually stimulating and soulful” and that show how music alone “absorbs” its creator’s feelings (Hanslick 2018, 45–46, 65), this view has been called into question. As Hanslick locates emotive meaning in music’s kinetic features that replicate the dynamic properties of affective conditions, his stance might come close to enhanced formalism (Cook 2001, 175). In view of Hanslick’s account of musical emotion as “silhouettes” (Hanslick 2018, 27) that open a certain variety of possible meaning whilst precluding capricious readings of music, he seems to regard musical elements as indefinitely expressive (Srećković 2014, 131)—an approach that anticipates Susanne K. Langer’s (1895–1985) theory of music as an “unconsummated symbol” (Wilfing 2016, 26–29).

d. The Musically Beautiful and Music’s Relation to History

Hanslick’s arguments regarding the complex relations between emotions and music, the indeterminate expressivity of musical gestures, as well as their debatable relevance for scientific aesthetics, however, merely apply to “pure” music. As vocal music forms an amalgam of music and poetry, the emotions aroused by it cannot be ascribed to any of its codependent components in arbitrary isolation. Thus, “pure” music—instrumental compositions without a literary program, title, or text—forms the basis of Hanslick’s aesthetics (Hanslick 2018, 23–26). This lopsided approach has led scholars to assume that Hanslick regarded vocal music as an impure blending of “absolute” art forms, whilst considering instrumental music to be the ideal form of music (Alperson 2004, 260; Gracyk, chap. 1). By contrast, other scholars stressed Hanslick’s statement that any leaning towards a specific subclass of music proves to be an “unscientific procedure” (Hanslick 2018, 24), and thus read Hanslick’s favoritism as a methodological consideration without normative implications (Bonds 2014, 12; Grey 2014, 44). For Hanslick, musical beauty is never based on the literary meaning or the emotive features of music but is rather found “solely in the tones and their artistic connection”: “The content of music,” as he famously proclaims, “is sonically moved forms” (Hanslick 2018, 40–41). The purport of Hanslick’s notorious sentence has evoked a wide array of possible readings. Although the “forms” he speaks about have been interpreted occasionally to refer to large-scale forms (concerto, sonata, rondo, and so on) and have thus been translated in the singular (Dahlhaus 1989, 130; Karnes 2008, 30), it seems likely that this term actually denotes musical elements and their structural conjunction (Wilfing 2018, sec. 3.3). In contrast, sonically or “tonally” (tönend), as Payzant renders this term (Hanslick 1986, 29), is an unclear concept that has been explained divisively. Whereas Payzant takes this term to refer to “tone” as part of the diatonic musical scale (2002, 44–46), Landerer and Rothfarb translate tönend as “sonically” and therefore emphasize its auditory features. Much of the question whether Hanslick perceived “pure” music to be captured entirely in the score itself (Subotnik 1991, 279; Alperson 2004, 266) or to require an auditory experience to be appreciated aesthetically (Bujić 1988, 10; Hamilton 2007, 82) hinges on the problematic translation of tönend.

Hanslick, however, willingly concedes that an assertive definition of the musically beautiful is virtually impossible to achieve because “pure” music cannot express concrete meaning. Any account of music’s content thereby amounts to “dry technical specifications” or “poetic fictions” (Hanslick 2018, 43). Music, in each case, must be understood musically and can be grasped only from within, as no verbal report can suffice. If we want to specify the content of a given theme for another person, “we have to play the theme itself for him” (Hanslick 2018, 113). Although Hanslick is unable to provide an exhaustive definition of musical beauty, he guards against potential fallacies: For him, the musically beautiful represents more than symmetry, regularity, proportion (Hanslick 2018, 57–59), or a pleasant sequence of tones, as these images neglect the crucial aspect of beauty: Geist (mind or intellect). The forms music consists of are “not empty but rather filled, not mere borders in a vacuum but rather intellect shaping itself from within” (Hanslick 2018, 43). Consequently, the act of composition is an “operation of the intellect in material of intellectual capacity” and the musically beautiful is produced primarily by the “intellectual power and individuality” of the composer’s imagination that has been absorbed by musical structure as a tonal idea that “pleases us in itself” (Hanslick 2018, 45–46). “Pure” music, Hanslick contends, has its own logic based on purely musical factors, the effect of which is governed by certain natural laws that have to be discovered, examined, and elucidated by aesthetic analysis (Hanslick 2018, 47–50). At this point, the tentative character of Hanslick’s approach becomes apparent, as he does not give any substantial indication as to how this goal could be realized beyond the idea that we must observe the efficacy of musical elements that are then reduced to general aesthetic categories that in turn lead to an ultimate principle. Although Hanslick cannot provide a conclusive treatment for scientific aesthetics, the pivotal insight of OMB seems clear: musical beauty depends on musical material and not on any concept or emotion. Thus, Hanslick wonders whether the divergent aesthetic qualities of musical artworks might hinge on the gradation or accuracy of emotional expression and answers in the negative: A piece shows more aesthetic qualities than another simply because it contains “more beautiful tone forms” (Hanslick 2018, 51).

Here, Hanslick mentions one of the few concrete examples of musical beauty by declaring creativity, originality, and spontaneity to be essential features of musical prowess. This view is notable because Hanslick’s notion of how musical beauty relates to history is one of the most divisive aspects of OMB. Hanslick’s emphasis on the intrinsic qualities of “pure” music, ruling out the various settings of creation, listening, or performance for aesthetic concerns, has led scholars to assume that Hanslick treats beauty ahistorically (Burford 2006, 172–73; Karnes 2008, 50–52; Bonds 2014, 176–77). This view is often based on Hanslick’s assurance that his concept of beauty applies to classicism as well as romanticism and thereby pertains to “every style in the same way, even in the most opposed ones” (Hanslick 2018, 55). Hanslick moreover advocates a categorical separation between historical reasoning and aesthetic judgment: whereas the historian’s exploration of the broader context of a given piece is undeniably warranted, aesthetic inquiry hears “only what the artwork itself articulates.” In regard to this hierarchy between the aesthetic relevance of artwork and context, Hanslick somewhat anticipates the New Criticism of 20th-century literary studies principally associated with Monroe C. Beardsley and William K. Wimsatt (Appelqvist 2010–11, 77–78). However, this idea is undermined immediately by Hanslick’s remarks on the indisputable connection of artworks to “the ideas and events of the time that produced them.” As music is created by an intellect, it stands in inextricable interrelation with concurrent productions of art and the “poetic, social, scientific conditions” of its time and place (Hanslick 2018, 55–56). For Hanslick, the aesthetic qualities of musical elements (particular cadences, intervallic progressions, modulations, and so on) are subject to historic decline and “wear out in fifty, even thirty years.” Eternal musical beauty is “little more than a nice turn of phrase” and we may say of compositions that “rank high above the norm of their time that they were once beautiful” (Hanslick 2018, 51, 58n). This theoretical contradiction prompted scholars to discern between Hanslick’s principle of scientific aesthetics, which is established ahistorically, and his concept of music itself and particular instances of the musically beautiful, which are subject to change (Landerer and Zangwill 2016, 490–92; Wilfing 2016, 17–18).

e. Listening, Music’s Relation to Nature, and Music’s Content

Although Hanslick openly rejects the listener’s relevance for the constitution of the musically beautiful that exists apart from the listener’s perception, the subjective impression of music forms the topic of chapters 4 and 5 of OMB. Hanslick is not at all interested in establishing a purely intellectual apprehension of musical structure. Beauty is rooted in (physical) sensation and engages the faculty of imagination as an intermediary between sensation, intellect, and feeling: listening to music in a purely rational fashion, Hanslick contends, is as far removed from aesthetic appraisal as mere affective arousal. The musical artwork acts as an “effective median between two animated forces,” the composer and the listener. The aesthetic exaltation of the composer’s imagination yields a theme shaped by the composer’s individuality, which is subsequently elaborated according to the artistic talents of its creator (Hanslick 2018, 63–64). The composer’s personality molds music’s “infinite capacity for expression” through his “consistent preference for certain keys, rhythms, [and] transitions” that transform the composer’s sensibility into a part of objective musical structure, which in turn is open to the listener’s perception (Hanslick 2018, 65). The listener’s judgment about the concrete meaning of a given piece is therefore affected heavily by performance, which allows the artist to release directly the emotion apparently perceived in music (Hanslick 2018, 67–69). For Hanslick, the genuine affective reaction of the listener, especially powerful in the case of music, is beyond dispute, but the ways in which it is constituted varies considerably. If the listener’s approach to “pure” music involves the attentive tracking of compositional development and therefore transcends emotional indulgence, the approach is aesthetical (Hanslick 2018, 88–90). If the emotive impact of music is received passively, however, the listener’s attitude is regarded as “pathological”—a term that carries medical connotations but derives chiefly from the Greek notion of “pathos,” thereby denoting purely passive experience (Hanslick 2018, 81–88). For Hanslick, this mode of listening originates from the physical aspects of sound and its direct effect on the human nervous system and thus lacks the necessary component of Geist to be considered aesthetical. It actually belongs to physiological, psychological, or medical research and is not subject to aesthetic inquiry (Hanslick 2018, 71–80).

Hanslick’s analysis of the complex interplay between composer, artwork, and listener is followed by an investigation of music’s relation to nature, arguably the oldest chapter of OMB. In general, artworks present a twofold relation to nature: first, through their physical material (sound, paint, stone); second, through the content nature affords to art. In the case of “pure” music, considered a cultural artefact, the physical material provided by nature merely amounts to “material for material” (wood, hide, hair) that is used to create actual musical material (tones, intervals, scales), already a product of culture (Hanslick 2018, 95). Nature thus merely offers physical material for acoustic material that in turn provides material for the creative activity of the individual composer, which builds upon the collective repository of music history. As musical content consists entirely of musical features, the origins of which are not natural, Hanslick moreover postulates that nature cannot provide content for “pure” music and thus does not have any relation to musical artworks. Whereas sculptors, painters, and writers are able to draw inspiration from human actions or nature itself, music finds no preceding prototype beyond the history of “artificial” musical material and is thus only akin to architecture. In blatant contrast to mimetic concepts of art, Hanslick thus holds that “the composer cannot transform anything, he has to newly create everything” (Hanslick 2018, 103). At this point, Hanslick once more illustrates the historical evolution of musical material, emerging gradually as a creation of intellect, by noting how certain modern intervals “had to be achieved individually” over multiple centuries. Music itself, in each of its various aspects, is created entirely by intellectual ingenuity and represents a “consequence of the endlessly disseminated musical culture.” Hanslick therefore overtly advises to “beware of the confusion as though this (present) tone system itself necessarily lies in nature” (Hanslick 2018, 95–97). As Hanslick’s concept of scientific aesthetics is based on material features of musical structure, this view has significant implications for his entire stance: since musical material will constantly undergo extension, any alteration pertaining to crucial aspects of musical technique will also affect the basics of aesthetic research (Hanslick 2018, 98–99).

Finally, Hanslick revisits the question of musical content in order to differentiate meticulously between distinct concepts of content usually lumped together indiscriminately. Content is defined as that “what something contains, holds within itself.” In the case of music, “content” denotes the tones and forms a piece of music is made of. This term is not to be confused with “subject matter” that typically indicates abstract literary content of which music has none: “music speaks not merely through tones, it speaks only tones” (Hanslick 2018, 108–109). In music, the concepts of content and form—musical material and its artistic design—mutually determine each other and are ultimately inseparable: “With music, there is no content opposed to form, because it has no form outside of the content” (Hanslick 2018, 111–12). A separation between musical content and its form does merely pertain to cases in which form is applied to large-scale structures, which is not the standard meaning of this term in OMB. Only then can the theme be called content, whereas the overall structure, the “architectonic of the joined individual components and groups of which the piece of music consists,” acts as form. The theme, which “develops in an organically, clearly organized, gradual manner, like luxuriant blossoms from a single bud,” constitutes the irreducible aesthetic “essence” of a piece of music. As everything in a specific musical structure is a “spontaneous consequence” of the initial theme, the multitude of prospects in which a theme could be developed determines its aesthetic substance or Gehalt: “whatever does not reside in the theme (overtly or covertly) cannot subsequently be organically developed” (Hanslick 2018, 113–14). Even though music does thus not present subject matter along the lines of literary meaning, “pure” music, animated by “thoughts and feelings,” does clearly exhibit intellectual “substance.” Generally speaking, “pure” music has content: purely musical content manifest in the distinct musical features of the theme, which Hanslick describes poetically as “spark of divine fire.” Musical content, Hanslick emphasizes in conclusion, purely derives from the “definite beautiful tone configuration” of a given piece as the “spontaneous creation of the intellect out of material of intellectual capacity” (Hanslick 2018, 114–16).

f. Conclusion: The Curious Nature of Hanslick’s Formalism

Hanslick’s aesthetics is frequently considered the “classical definition of formalistic aesthetics in music” (Yoshida 2001, 179) and the “inaugural text in the founding of musical formalism as a position in the philosophy of art” (Kivy 2009, 53). What is meant by musical formalism and which exact version of musical formalism Hanslick is supposed to represent, however, is one of the divisive questions of Hanslick scholarship and of the philosophy of music at large. The conceptual significance of the term ‘form’ and its relevance for Hanslick’s theory seem to be overrated in principle. Philosophical commentators typically overlook that Hanslick’s definition of beauty in music—the focal point of OMB—does not rely upon any idea of form and that this term is indeed absent from Hanslick’s description of music’s artistic quality: by specific musical beauty, Hanslick designates a “beauty that is independent and not in need of an external content, something that resides solely in the tones and their artistic connection” (Hanslick 2018, 40). Furthermore, Hanslick’s infamous statement of “sonically moved forms” did not correspond to music itself, as is surmised regularly, but much more narrowly to music’s content that is thereby equated with form, and vice versa. Even the more pointed version in the second edition of OMB, which states that forms are “solely and exclusively the content and subject of music” did not identify form with music itself but rather claims the identity of the content and forms of music (Hanslick 2018, 41). Thus, these forms are not without content or thought of as empty but rather are imbued by intellect (Geist) “shaping itself from within” (Hanslick 2018, 43), thereby linking beauty to mental activity (Bowman 1991, 47; Paddison 2002, 335; Burford 2006, 179). Hanslick therefore opposes one of the central claims of formalist aesthetics that usually stresses the primacy of formal features over some kind of content (Fisher 1993, 250; Kivy 2002, 67; Beard and Gloag 2005, 65). In music, he states, “we see content and form, material and design, image and idea fused in an obscure, indivisible unity,” which means that “there is no content opposed to form” as music “has no form outside of the content” (Hanslick 2018, 111–12). By stating that form and content are one, Hanslick is “almost alone among formalists” (Payzant 2002, 83) and OMB thus even “reads more like a traditional criticism of formalism” (Hamilton 2007, 88).

Whether Hanslick’s aesthetics is to be regarded as formalist, however, depends entirely on the definition of formalism espoused by scholars. The special variety of Hanslick’s approach is clarified by one of the customary definitions of formalist aesthetics, the conception of formalism as common denominator argument (Carroll 1999, chap. 3 and 2001). In this case, formalism is understood as a universal definition of art, such as in Clive Bell’s (1881–1964) formalist manifesto Art, which posits a circular concept (Gardner 1996, 238; Carroll 2001, 95; Stecker 2003, 141) of “aesthetic emotion” elicited by “significant form” that “distinguishes works of art from all other classes of objects” and thereby defines the fine arts as such (Bell 1914, 13). Formalists, as Dziemidok (1993, 192) states, “strive to determine general criteria of valuation universally applicable to all art forms” and thus miss the “values unique” to each artistic medium by commencing with “universalistic assumptions.” As we have seen in sec. 3.b, this definition of formalism contradicts Hanslick’s insistence on the idea that the criteria of the musically beautiful apply solely to music itself and not to the other art forms. Further concepts of general aesthetic formalism prove to be similarly debatable: Small (1998, 135), for example, describes formalist theories as denying that “emotions have anything to do with the proper appreciation of music” (form versus emotion/content), while Mothersill (1984, 222) emphasizes formalism’s conviction that “elements which suggest or establish a link between the artwork and the world should be disregarded” (form versus context). In view of OMB, both ideas seem somewhat applicable but at the same time miss something important about Hanslick’s viewpoint: whereas aesthetic analysis—conceived as an objectivist scientific approach—is indeed distinct from historical concerns and the stimulation, expression, or portrayal of definite emotion, music itself affects emotion and is connected intimately to concurrent productions of art and the “poetic, social, scientific conditions” of its time and place (Hanslick 2018, 9, 55; cf. Wilfing 2016, 15–18). In general, any detailed appraisal of Hanslick’s formalism does hinge upon the individual definition of aesthetic formalism and ‘form’ itself—a term that is as ambiguous as it is persistent (Tatarkiewicz 1973, 216), which might be of limited efficacy in describing Hanslick’s argument and must thus be employed carefully (Nattiez 1990, 109; Bowman 1991, 53; Payzant 2002, 58).

4. The Intellectual Background of Hanslick’s Aesthetics

a. Hanslick and German Idealism

Historical research on OMB is dominated primarily by questions of intellectual dependency: Who influenced Hanslick’s aesthetic approach and which philosophical movement stimulated the main ideas of his aesthetic approach (Landerer and Wilfing 2018)? Numerous candidates have been invoked as precursors to Hanslick’s “formalism,” ranging from idealist theorists—Kant (1724–1804), Herder (1744–1803), Hegel (1770–1831), Schelling (1775–1854), Vischer (1807–87)—and German poetry—Lessing (1729–81), Goethe (1749–1832), Schiller (1759–1805), or the German literary romantics—to the Austrian context of Hanslick’s aesthetics and “minor” figures such as Michaelis (1770–1834), Novalis (1772–1801), or Nägeli (1773–1836). Generally speaking, current scholarship situates Hanslick’s argument in the (ultimately antithetic) traditions of German idealism and Austrian realism. The most prominent contender as the crucial source of OMB, emphasized particularly in analytical philosophy (Gracyk, chap. 1; Appelqvist 2010–11, 76; Davies 2011b, 297), is Kant’s Kritik der Urteilskraft (Critique of the Power of Judgment, 1790). As OMB is typically regarded as the classical definition of formalistic aesthetics in music and Kant’s Kritik is widely thought to be the origin of general aesthetic formalism, this link appears entirely natural (Ginsborg 2011, 334). Their respective definition of aesthetic intuition as disinterested contemplation, standing apart from rational thought and affect states, as well as their general concept of beauty, which is not subject to an external purpose or definite concepts, establish Hanslick’s awareness of Kant’s theory. Whether Hanslick, who did not receive any formal training in philosophy, ever read Kant or whether he adopted certain notions from post-Kantian aesthetic discourse (Dambeck, Michaelis, Nägeli, and so forth) is open to debate. Although Hanslick’s reliance on Kant’s theory is frequently accepted as fact, this view is complicated by at least three issues: (1) Kant’s notion of music as a servant of poetry and as a language of affect states was criticized vigorously by Hanslick. (2) Hanslick’s concept of specific musical beauty directly opposes Kant’s idealist attitude, which stipulates an abstract principle of beauty, administered retroactively to each art form. (3) The objectivist approach of Hanslick’s aesthetics contradicts Kant’s transcendental methodology, the crucial premise of his entire system (Bonds 2014, 188–89; Wilfing 2018, sec. 3.3).

While Kant is mentioned only once in OMB as one of those “eminent people” who did reject any literary content when it came to music (Hanslick 2018, 107), a different contender as the pivotal source of Hanslick’s aesthetics is referred to on multiple occasions: Hegel. Although a large share of Hanslick’s comments on Hegel are intended as criticism—he accuses Hegelian theories of an “underevaluation” of sensuousness in favor of ideas, for example (Hanslick 2018, 42)—various quotes and his early music reviews confirm that Hanslick was familiar with Hegel’s aesthetic positions. The theoretical importance of Hegel’s Vorlesungen über die Ästhetik (Lectures on Aesthetics, 1835–38) for the basic tenets of Hanslick’s approach have been investigated particularly by Carl Dahlhaus, who supported his viewpoint by drawing attention to Hanslick’s persistent utilization of the term Geist, which also permeates Hegel’s philosophy. Dahlhaus, however, did not regard Hanslick’s treatise as an uncritical extension of Hegel’s theory of art as the corporeal incarnation of the idea, in which music itself is only form, whereas thoughts and feelings are the content (Dahlhaus 1989, 110). For him, Hanslick’s theory inverts Hegel’s system by making the idea purely musical and thereby turning “form” into a concept of the interior, not the exterior (Burford 2006, 170; Bonds 2012, 8). Although Hanslick’s definition of composing as “intellect shaping itself from within” is probably situated in a general setting of Hegelian reasoning, the whole extent of Hanslick’s awareness of Hegel’s writings is unknown, as no related records survive. The situation is different, however, if we turn to Hegelian aesthetic theorists: We know that he read parts of Vischer’s Aesthetik oder Wissenschaft des Schönen (Aesthetics or Science of Beauty, 1846–57), for example, which might have been the most likely source for his Hegelian leanings (Titus 2008). Hanslick candidly criticized Hegelian aesthetics for its historical orientation, which seemingly confused historical research with aesthetic analysis, but he nonetheless emphasized the historical evolution of musical material and the arbitrary appraisal of specific artworks. The idea that artistic material does not merely consist of physical elements (sound, paint, stone), but moreover comprises the entire historical evolution of each art form—the historical interplay between material and mind—was a central concept of Vischer’s theory, linking Hanslick’s approach to Hegelian aesthetics.

b. Hanslick and Austrian Realism

As an Austrian theorist raised in Prague who spent most of his career in Vienna, the delineated relevance of German idealism for the basic tenets of OMB has to be supplemented by an analysis of Hanslick’s Austrian contexts. In the 19th century, Austrian science policies were strongly opposed to philosophical “speculation” that was held responsible for the societal upheaval in the wake of 1789 and 1848. These events caused several reforms of the Austrian school system, the primary purpose of which should be to foster the restoration endeavors of the Habsburg leadership by confining education to propaedeutic instructions compatible with Catholic dogmas and state norms. This political strategy resulted in the preservation of Leibnizian philosophy, the flourishing of positivistic scholarship, and the inhibition of German idealism in favor of methods perceived as decidedly scientific. One intellectual, who consciously modernized the Leibnizian framework engrained in the academic landscape of Austria, was the Prague priest and philosopher Bernard Bolzano (1781–1848). Although Bolzano was forced to resign owing to an unfounded accusation of Kantianism in 1819, the general precepts of his writings prospered in Habsburg territories by way of his scientific successor and Hanslick’s close friend Robert Zimmermann (1824–98), who attained a tenured position at the University of Vienna in 1861. Bolzano published his aesthetic doctrines in Über den Begriff des Schönen (On the Notion of Beauty, 1843) and Über die Eintheilung der schönen Künste (On the Classification of the Fine Arts, 1849). In similar fashion to Hanslick, he defined aesthetic perception as disinterested contemplation, construed musical listening as an intentional monitoring of compositional development, and dismissed emotivist models whilst insisting on particular aesthetics for each art form. Bolzano’s most significant contribution to Hanslick’s aesthetics, however, was his drastically objectivist approach isolated entirely from psychological explanations that might derive from Bolzano’s theory of science. Here, Bolzano outlines his Platonic concept of a “truth as such,” which states something as is, no matter whether this fact has been or ever will be uttered or thought by anyone. The radically objective condition of Hanslick’s concept of musical beauty, which remains beauty “even if it is neither viewed nor contemplated,” matches Bolzano’s Platonic mindset (Bonds 2014, 162; Wilfing 2018, sec. 2).

Another important precursor to Hanslick’s aesthetics, who is significant particularly due to his influence on Austrian science policies in general, is Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776–1841). As Herbart declared natural science the operational benchmark for philosophy and demanded a separation between philosophy, religion, and politics, his approach blended perfectly with the positivistic endeavors of Habsburg authorities and thereby became the semi-official philosophy of Austria. This gradual process was completed by the school reform of 1849, the leading figures of which closely adhered to Herbartian teachings (Landerer and Wilfing 2018, sec. 4), including Zimmermann, Hanslick’s former teacher Franz Exner (1802–53) and his old associate Joseph von Helfert (1820–1910). Hanslick, who attained a position at the ministry of education in 1854, recognized the importance of employing Herbartian principles in OMB, which should set the stage for his academic profession (Payzant 2002, 131). It thus comes as no surprise that Hanslick declared himself a follower of Herbart in his successful habilitation petition of 1856. As recent studies demonstrated convincingly, however, this personal testimony is probably nothing more than an allusion provoked by careerist concerns (Karnes 2008, 31–34; Bonds 2014, 159; Landerer and Zangwill 2016, 90–91). An immediate reference to Herbart is totally absent from earlier editions of OMB, where he is belatedly included in the third edition of 1865 and the sixth edition of 1881 (Hanslick 1986, 77, 85). In spite of this lack of quotes and in view of Herbart’s bearing on Austrian science policies, it is difficult to imagine that Hanslick was completely unfamiliar with Herbart’s ideas prior to the initial edition of 1854. In regard to Hanslick’s argument, Herbartian teachings seem to be important specifically for his formalist approach, for his theory of autonomous instrumental music, for his refutation of emotivist aesthetics, for his emphasis on elemental components of “pure” music and their mutual relations, and for his appreciation of technical musical analysis (Bujić 1988, 7–8; Bonds 2014, 158–62; Wilfing 2018, sec. 2). Generally speaking, the writings of Bolzano and Herbart were similar in various respects—a fact that lead to the frequent blending of their work in post-1848 Austria. Specific features of OMB, however, are decidedly Herbartian, such as Hanslick’s concept of emotion deriving from Herbart’s cognitivist reductionism that regards feelings as a subclass of Vorstellungen or presentations (Landerer and Wilfing 2018, 49n).

c. Editorial Problems and Eclectic Origins of OMB

The Austrian contexts of Hanslick’s aesthetics were supremely important for the contentual alterations following the initial edition of OMB (Landerer and Wilfing 2018, sec. 4). The most striking example of these severe changes, owing to the scientific landscape of contemporary Austria, is the removed final paragraph of Hanslick’s classic treatise. OMB originally concluded in idealist fashion, linking the musically beautiful with “all other great and beautiful ideas.” As “pure” music ultimately represents a sounding portrayal of the motions of the cosmos, it eventually transcends its conceptual limitations, “allowing us to feel… the infinite in works of human talent.” The vital traits of musical structure (harmony, rhythm, sound), Hanslick proclaims, permeate the universe so that one can “find anew in music the entire universe” (Bonds 2012, 4; cf. Hanslick 2018, 120). This original ending of OMB evidently betrayed remnants of German idealism and therefore countered Austrian science policies. This discrepancy was pointed out to Hanslick by the foremost Herbartian philosopher of his time and place: Zimmermann. In an extensive review, published in 1854, he commended the positivistic orientation of Hanslick’s argument that apparently conformed to Herbartian aesthetics, but at the same time criticized the idealist notions present in OMB. According to Zimmermann, the idea that the musically beautiful is completely autonomous epitomized the crucial insight of Hanslick’s argument. For him, this advantage of Hanslick’s aesthetics was compromised by his concession to an aesthetics dependent on speculative metaphysics (Bonds 2012, 5–6). As this public review outlined the Herbartian sentiments of Habsburg authorities responsible for his future career, Hanslick deleted the closing remarks as well as additional passages evocative of his former idealist stances (Landerer and Zangwill 2016; Sousa 2017). It is for this reason that the historical reception of OMB in anglophone scholarship was impacted markedly by Hanslick’s alterations: whereas German-language discourse is based mostly on the initial edition of OMB, its translations utilized editions 7 (Cohen), 8 (Payzant), and 10 (Rothfarb and Landerer) that read more formalistic and positivistic than earlier versions. As the deleted ending of OMB was translated for the first time as late as 1988 (Bujić 1988, 39) and was not discussed seriously by anglophone academics prior to Bonds’s studies, one can get the impression that scholarship in German and English addresses quite different books (Payzant 2002, 44).

A relevant outcome of current research into Hanslick’s intellectual background, however, is the emerging realization that Hanslick’s aesthetics draws upon a wide array of assorted aesthetic discourses integrated into OMB. It is no contradiction that Hanslick’s emphasis on structural relations between musical elements is derived from Herbartian aesthetics, whilst his concurrent refutation of psychological considerations—supremely important for Herbartian aesthetics—appears to be closer to Bolzano. The same applies to Hanslick’s Vischerian concept of historical evolution, overtly opposing the ahistorical orientation of Herbartian aesthetics, and his anti-Hegelian insistence on a categorial distinction between the methods of historical and aesthetic research derived from Herbartian philosophy (Edgar 1999, 443–44; Landerer and Zangwill 2017, 93–94). Hanslick’s textual strategy frequently resembles a virtual collage as in a passage reworded for the second edition of 1858: Hanslick defends that beauty remains beauty “even when it arouses no emotions, indeed when it is neither perceived nor contemplated. Beauty is thus only for the pleasure of a perceiving subject, not generated through that subject” (Bonds 2014, 189; cf. Hanslick 2018, 4). The first part of Hanslick’s quotation is adopted directly from Zimmermann’s review and might even have an immediate antecedent in Bolzano, the former teacher of Zimmermann. Bolzano makes a similar objectivistic statement in On the Notion of Beauty by stating that beauty would remain beauty “even if there existed only one human being in the entire world or no one at all.” The first part of the second sentence, however, alludes to Vischer’s Aesthetics and his concept of Anschauung (perception), thereby directly linking the opposing approaches of Herbartianism and Hegelianism. Hanslick purposely disregards Zimmermann’s ensuing assertion that beauty is based on constant relations between aesthetic properties and thus does not change over time as he acknowledged the historical condition of music and beauty (Landerer and Wilfing 2018, sec. 3). Generally speaking, Hanslick’s argument comprises a multitude of diverse sources—which at times are blatantly antithetic—and his intellectual background is therefore difficult to reconstruct thoroughly. His “eclectic” approach, however, ensured the remarkable durability of Hanslick’s aesthetics, which was not bound by the rise and fall of isolated academic traditions (Bujić 1988, 8).

5. The Reception of Hanslick’s Aesthetics and Its Relevance to Current Discourse

a. A General Outline of Hanslick’s Reception by Austro-German Discourse

The historical reception of Hanslick’s aesthetics, stretching from Viennese Modernism, the beginnings of musicology, and numerous composers to significant philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche (1884–1900), Theodor W. Adorno (1903–69), Langer, and analytical aesthetics in general, for the most part represents “terra incognita” (Deaville 2013, 25). Scholarship on Hanslick’s reception is typically restricted to incidental references to conceptual similarities between Hanslick and certain later authors. OMB is mentioned by Karl Popper (1902–94), for example, and probably affected his objective aesthetic approach, his wariness regarding psychological argumentation, and his rejection of emotivism. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s (1889–1951) late work is similarly evocative of Hanslick’s approach, as he declares musical meaning to be purely musical and repudiates the idea that “pure” music could be translated adequately into other modes of expression (Ahonen 2005, 520–23; Szabados 2006, 651–53). Adorno’s adoption of Hanslick’s dynamism (Goehr 2008, 20; Paddison 2010, 131–34) and his distinction between different attitudes towards musical listening betray Hanslick’s impact as much as Adorno’s concept of the historical evolution of musical material (Edgar 1999, 441–44; Paddison 2002, 336), firmly rooted in Hegelian aesthetics. Hanslick’s influence on Nietzsche is particularly remarkable as it spans from his earliest writings to his late work. His vigorous criticism of Wagner in Der Fall Wagner (The Case of Wagner, 1888) and Nietzsche contra Wagner (1889) is inspired evidently by Hanslick’s writings, replicated virtually verbatim on numerous occasions. OMB similarly influenced young Nietzsche, who studied Hanslick’s treatise as early as 1865 and employed Hanslick’s argument in fragment 12[1] of 1871 on the relation between language and “pure” music. Here, Nietzsche verbalizes doctrines that are far more indicative of his eventual refutation of Wagner’s oeuvre than his Geburt der Tragödie (Birth of Tragedy, 1872), written at the same time, might suggest. Scholars have thus assumed a rather brief period of unwavering enthusiasm for the Bayreuth composer (Prange 2011). No philosophical movement, however, has addressed Hanslick’s aesthetics as fruitfully as analytical philosophy, particularly so due to its strong focus on the expressive capabilities of “pure” music.

b. Hanslick’s Reception by Analytical Aesthetics and the Direct Impact of OMB

The crucial feature of analytical philosophy is its methodic scientism as the foundation for all philosophy and all knowledge acquisition in general. Current research into the key attributes of analytical aesthetics regularly highlights its tendency to detach the targets of analysis from various contexts in order to establish the possibility of objective observation (Roholt 2017, 50–51). Hanslick’s positivist approach targeted towards scientific objectivity, his strong appeal to natural science as a guideline for objective aesthetics, and his procedural dissociation of musical artworks from external contexts that are not relevant for aesthetic purposes concurs with this provisional description of analytical philosophy of music. Historically, Hanslick’s aesthetics was perceived as an important corrective to the “fantastic nonsense” and “sentimental speculations” of idealist theories (Lang 1941, 978; Epperson 1967, 109–10) and therefore contributed to the anti-idealist movement of analytical philosophy aimed against Hegelians such as Francis Bradley (1846–1924), Bernard Bosanquet (1848–1923), or John McTaggart (1866–1925). Early analytical aesthetics of the 1950s and 1960s, which initially needed to cast off its widespread reputation of conducting unscientific guesswork, was concerned principally with abstract problems and attempted to determine an exhaustive definition of art, the quality and quantity of aesthetic properties, and the peculiarity of aesthetic perception (Goehr 1993; Lamarque 2000). Even though this focal point of anglophone philosophy left no room for OMB and its emphasis on musical artworks, Hanslick’s treatise gained traction the moment aesthetics redirected its inquiry towards more concrete subjects. Works on issues related to music, increasing strikingly in the 1980s (Lamarque 2000, 14; Davies 2003, 489), proceeded from influential publications by Budd, Davies, and Kivy (all 1980) that featured Hanslick’s aesthetics markedly and set the scene for ensuing decades of anglophone philosophy of music (Davies 2011b, 294). Each of their texts is focused on problems of musical expression and drew from Hanslick’s cognitive concept of emotion, resembling the approach developed by Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer in the 1960s. Thus, the development of aesthetics concerned with specific objects and the establishment of cognitivist psychology coincide with and form the basis of Hanslick’s fruitful reception by analytical aesthetics.

Hanslick’s theories, the impact of which has even been compared to David Hume’s (1711–76) historic critique of speculative philosophy (Hanslick 1957, vii), shaped the general position on musical meaning in anglophone philosophy. Even though hardly any current approach concurs entirely with Hanslick’s aesthetics (Zangwill 2004 is a prominent exception), his momentous formulation of certain issues continues to dominate aesthetic discourse (Maus 1992, 273; Davies 2003, 492; Hamilton 2007, 82). This fact is exemplified particularly by authors who discard OMB and its cognitivist orientation, but nonetheless acknowledge that his views are permeating anglophone philosophy (Madell 2002, 1–9). His cognitive hypothesis, however, was not the only argument espoused by analytical academics, who also drew from more specific aspects of OMB. Hanslick’s rejection of basic forms of musical expression, treating affective features as a direct result of the composer’s emotional condition (Hanslick 2018, 63–65), for example, is basically accepted by modern research (Kivy 1980, 14–15; Davies 1986, 148; Naar, chap. 3b). Hanslick justifies this view with the theoretical redundancy of an aesthetic approach that traces the cause of emotional expression to a source located outside of art. Musical expression is successful principally in virtue of the expressive properties of music chosen to indicate a specific feeling and cannot be explained by reference to the artist’s affect states, already absorbed by his creation (Kivy 2009, 250; Davies 2011a, 23; Gracyk 2013, 78–79). Another argument aimed against arousal theories that has been discussed frequently by anglophone philosophers, and that was coined mainly by Budd (1985, 125), is the “heresy of the separable experience” (Ridley 1995, 38–49; Scruton 1997, 145–46; Madell 2002, 32, 57, 99). If musical expression is dependent on the response of the listener, music might become nothing more than a random medium of transference, which could be replaced by objects causing an identical response, and loses sight of the individuality of the composition (Hanslick 2018, 91–92). Hanslick proposes that causal theories cannot explain the unique quality of musical artworks as they tend to regard music as a device for affective arousal that could just as well be realized by a warm bath, a cigar, chloroform (Hanslick 2018, 83), or by a drug causing feelings (Kivy 1989, 218, 222, 242; Matravers 1998, 169–85; Robinson 2005, 351, 393, 397).

c. Bypassing Hanslick’s Cognitivist Arguments: Kivy, Davies, and Moods

As we have seen, important objections directed against current theories of musical arousal and expression propounded by anglophone philosophers stem from Hanslick’s aesthetics and extend beyond the cognitivist hypothesis of OMB. His cognitivism is therefore frequently considered the strongest argument that emotivist aesthetics has substantial weaknesses (Kivy 1989, 157; Davies 1994, 209). Hanslick’s (implicit) concept of indeterminate expressivity (Wilfing 2016, 26–29) suggests that emotion is an inherent property of musical structure—an idea that laid the ground for the enhanced formalism of Davies and Kivy, which is based on the similarity perceived between musical motions and the outward features of human emotion. Enhanced formalism does not hold that music refers beyond itself to occurrent emotions but considers expression an objective property of musical structure: music itself is the owner of the emotion it expresses (Davies 1980, 68; Kivy 1980, 64–66). Hanslick, however, had good reasons to abandon enhanced formalism as the theoretical foundation of scientific aesthetics—reasons that paved the way for another argument crucial to analytical aesthetics: the argument from disagreement (Gardner 1996, 245–46; Sharpe 2004, 19–20). While Davies (1994, 213–15) and Kivy (1990, 175–77) fully agree that “pure” music cannot express Platonic attitudes (emotions such as pride or shame that involve complex concepts), they hold that it is able to portray definite emotional properties of a lower order. Hanslick’s attitude is even more skeptical: As the dynamic character of affect states is only one moment of emotion, not emotion itself, music can merely allude to a certain variety of affect states, not to any sentiment in particular, and any survey among an audience regarding the emotion ascribed to a piece would thus yield varied results (Hanslick 2018, 23). As enhanced formalism is based on the semblance perceived between musical motion and emotive behavior, Davies and Kivy needed to dismiss Hanslick’s claim about considerable disagreement by gradually retreating to more and more general emotions, which serve as umbrella concepts for specific emotions (Kivy 1980, 46–48; Davies 1994, 246–52). Other scholars pointed to Hanslick’s metaphor of expressive silhouettes and construed his argument in terms of indeterminate expressivity along the lines of Rorschach’s inkblot testing, thereby updating Hanslick’s argument for modern debates (Ahonen 2007, 93).

Generally speaking, OMB introduced numerous important arguments to analytical aesthetics that remain the subjects of current research, such as the famous paradox of negative emotion, which Hanslick directed against theories of musical arousal. If every death march or every somber adagio, Hanslick declares, had the power to elicit grief in the listener, nobody would bother with such works (Hanslick 2018, 90–91). Solutions to Hanslick’s question vary from the rejection of emotive arousal (Kivy 1989, 234–59) and accounts of the way negative emotions have beneficial pedagogic effects (Levinson 1982; Davies 1994, 307–20; Ridley 1995, chap. 7) to revised arousal theories that hold that emotional reactions to music rarely mirror the feeling depicted by a given piece (thus, a somber adagio could arouse compassion instead of sorrow; Matravers 1991 and 1998, chap. 8). Finally, Hanslick’s cognitivist formalism has contributed to a noticeable reframing of the general approach to emotive musical meaning. Matravers, for example, asserted that a piece of music would depict a specific emotion if it arouses a feeling, the physiological components of which would correspond to the emotion depicted (Matravers 1998, 149). As music cannot portray the cognitive elements of genuine emotions, Hanslick’s argument is bypassed by an appeal to feeling as the somatic feature of emotion, which music is able to prompt directly (Matravers 1991, 328). Ridley, who endorses Hanslick’s cognitive objection to common arousal theories, shares this idea by considering “objectless passions” as feelings, the gestural character of which is evoked by the dynamic qualities of music (Ridley 1995). Thus, OMB and its cognitivist orientation occasioned a shift from issues of emotional expression to issues of music’s relation to non-cognitive affect states—a shift also made clear by an increased discussion on music and moods (Radford 1991; Carroll 2003; Sizer 2007). Although OMB has thus come under attack in anglophone philosophy, the constant rebuttal of Hanslick’s aesthetics at the same time illustrates the degree to which his approach is ingrained in analytical philosophy in regard to questions of musical meaning. The lion’s share of theorists continues to consider Hanslick’s cognitive argument to be accurate in principle and adjusts their models of expressivity accordingly. Hanslick’s influence on current debates thus goes beyond the assenting reception of OMB and thereby remains equally present in modern theories intentionally sidestepping the key argument of Hanslick’s approach.

6. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

- Hanslick, Eduard. 1950. Music Criticisms, 1846–1899. Translated by Henry Pleasants. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Hanslick, Eduard. 1957. The Beautiful in Music: A Contribution to the Revisal of Musical Aesthetics. Edited by Morris Weitz. Translated by Gustav Cohen. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Hanslick, Eduard. 1986. On the Musically Beautiful: A Contribution Towards the Revision of the Aesthetics of Music. Translated by Geoffrey Payzant. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Hanslick, Eduard. 1993. Sämtliche Schriften: Historisch-kritische Ausgabe. Vol. 1, Aufsätze und Rezensionen 1844–1848. Edited by Dietmar Strauß. Vienna: Böhlau.

- Hanslick, Eduard. 1994. Sämtliche Schriften: Historisch-kritische Ausgabe. Vol. 2, Aufsätze und Rezensionen 1849–1854. Edited by Dietmar Strauß. Vienna: Böhlau.

- Hanslick, Eduard. 2018. On the Musically Beautiful: A New Translation. Translated by Lee Rothfarb and Christoph Landerer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

b. Secondary Sources

- Ahonen, Hanne. 2005. “Wittgenstein and the Conditions of Musical Communication.” Philosophy 80: 513–29.

- Ahonen, Hanne. 2007. “Wittgenstein and the Conditions of Musical Communication.” PhD diss., University of Columbia.

- Alperson, Philip. 1984. “On Musical Improvisation.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 43, no. 1: 17–29.

- Alperson, Philip. 2004. “The Philosophy of Music: Formalism and Beyond.” In The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics, edited by Peter Kivy, 254–75. Malden: Blackwell.

- Beard, David, and Kenneth Gloag. 2005. Musicology: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge.

- Bell, Clive. 1914. Art. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Bonds, Mark Evan. 2012. “Aesthetic Amputations: Absolute Music and the Deleted Endings of Hanslick’s Vom Musikalisch-Schönen.” 19th-Century Music 36, no. 1: 3–23.

- Bonds, Mark Evan. 2014. Absolute Music: The History of an Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bowman, Wayne D. 1991. “The Values of Musical ‘Formalism’.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 25, no. 3 (1991): 41–59.

- Brodbeck, David. 2007. “Dvořák’s Reception in Liberal Vienna: Language Ordinances, National Property, and the Rhetoric of ‘Deutschtum’.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 60, no. 1: 71–132.

- Brodbeck, David. 2009. “Hanslick’s Smetana and Hanslick’s Prague.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 134, no. 1: 1–36.

- Brodbeck, David. 2014. Defining ‘Deutschtum’: Political Ideology, German Identity, and Music-Critical Discourse in Liberal Vienna. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Budd, Malcolm. 1980. “The Repudiation of Emotion: Hanslick on Music.” British Journal of Aesthetics 20, no. 1: 29–43.