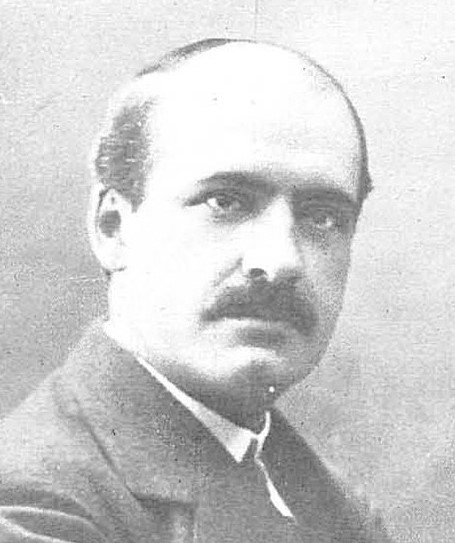

José Ortega y Gasset (1883—1955)

In the roughly 6,000 pages that Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset wrote on the humanities, he covered a wide variety of topics. This captures the kind of thinker he was: one who cannot be strictly categorized to any one school of philosophy. José Ortega y Gasset did not want to constrain himself to any one area of study in his unending dialogue to better understand what was of central importance to him: what it means to be human. He wrote on philosophy, history, literary criticism, sociology, travel writing, the philosophy of life, history, phenomenology, society, politics, the press, and the novel, to name some of the varied topics he explored. He held various identities: he was a philosopher, educator, essayist, theorist, critic, editor, and politician. He did not strive to be a “professional philosopher”; rather, he aimed to be a ‘philosophical essayist.’ While there were many reasons for this, one of central importance was his hope that with shorter texts, he could reach more people. He wanted to have this dialogue not only with influential thinkers from the past, but with his readers as well. Ortega was not only one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century from continental Europe, but he also had an important impact on Latin American philosophy, most especially in introducing existentialism and perspectivism.

In the roughly 6,000 pages that Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset wrote on the humanities, he covered a wide variety of topics. This captures the kind of thinker he was: one who cannot be strictly categorized to any one school of philosophy. José Ortega y Gasset did not want to constrain himself to any one area of study in his unending dialogue to better understand what was of central importance to him: what it means to be human. He wrote on philosophy, history, literary criticism, sociology, travel writing, the philosophy of life, history, phenomenology, society, politics, the press, and the novel, to name some of the varied topics he explored. He held various identities: he was a philosopher, educator, essayist, theorist, critic, editor, and politician. He did not strive to be a “professional philosopher”; rather, he aimed to be a ‘philosophical essayist.’ While there were many reasons for this, one of central importance was his hope that with shorter texts, he could reach more people. He wanted to have this dialogue not only with influential thinkers from the past, but with his readers as well. Ortega was not only one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century from continental Europe, but he also had an important impact on Latin American philosophy, most especially in introducing existentialism and perspectivism.

Table of Contents

- Biography

- Philosophy of Life

- Perspectivism

- Theory of History

- Aesthetics

- Philosophy

- The History of Philosophy

- References and Further Reading

1. Biography

José Ortega y Gasset was born in 1883 in Madrid and died there in 1955 after spending many years of his life in various other countries. Throughout his life, Ortega was involved in the newspaper industry. From an early age he was exposed to what it took to run and write for a newspaper, which arguably had an important impact on his writing style. His grandfather was the founder of what was for a time a renowned daily paper, El Imparcial, and for which Ortega wrote his first article in 1904—the same year he received his Doctorate in Philosophy from the Central University of Madrid. His dissertation was titled The Terrors of Year One Thousand, and in it we see an early interest in a topic that he would explore profoundly: the philosophy on history. While he was finishing his dissertation, he also met his wife, Rose Spottorno, with whom he had three children.

Ortega spent time abroad in Germany, France, Argentina, and Portugal. Some of those years were spent in exile, as he was a staunch critic of Spanish politics across the spectrum. Though he wavered at times as to which political philosophy he was most vocal about, he was quite vociferous against both communism and fascism. Thus, it is not always clear what Ortega’s political views were, and he was also at times misappropriated by some important politicians of the time. For example, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the son of the military dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera and founder of the Falange, the Spanish Fascist party, arguably greatly misappropriated Ortega’s political philosophy to best suit his own needs. For a time, Ortega supported Rivera, but he came to be vehemently opposed to any kind of one-man rule. He was also initially in support of the Falange and their leader, General Francisco Franco, but eventually also became very disillusioned with them. However, during the Spanish Civil War from 1936-1939, he remained quite silent, probably to ultimately express his dissatisfaction with the aims of both sides. Still, given the ambiguities in his writings, they were misappropriated by both ends of the political spectrum in Spain. This confusion can also be seen in comments such as his ‘socialist leanings for the love of aristocracy.’ Ortega retired from politics in 1933, as he was ultimately more interested in bringing about social and cultural change through education. After 1936, the great majority of his writing was of a philosophical nature.

Being too silent on certain issues, such as on the Spanish Civil War and on Hitler and the Nazis, also brought him some controversy. He did have some bouts of depression, which may have coincided at times with this lack of commentary on the Second World War. At times he longed to be in a place that enabled him to experience some sort of neutrality, which is something that drew him to Argentina. From 1936 until his death in 1955, he suffered from poor health and his productivity declined dramatically. Still, his lack of outspoken criticism of Nazism has not been fully explained. War was one of the few central topics of his day that he wrote little on, because he presumably held the position that words cannot compete with weapons in a time of war.

He also had periods in which he leaned toward socialism. But, essentially, none of the traditional or dominant political views of the time would suffice, and ultimately, he promoted his own version of a meritocracy given his dissatisfaction with democracy, capitalism, bolshevism, fascism, and his revulsion of the type of mass-person that had developed during his lifetime. Despite much confusion regarding his political views, they can perhaps be summarized best as the promotion of a cultured minority in which economic and intellectual benefits trickle down to the rest of society. Possibly, the best classification would be that of a selective individual, a meritocratic-based version of liberalism.

In 1905 he began the first of three periods of study in Germany, which was an eight-month stay at the University of Leipzig. In 1907 he returned to Germany with a stipend and began his studies at the University of Berlin. Sixth months later he went to the University of Marburg, and this experience was particularly influential. He was initially quite drawn to the Neo-Kantianism prevalent there from his studies under Hermann Cohen and Paul Natorp. This influence of idealism is quite prevalent in his first book, Meditations on Quixote, which he published at the age of thirty-two (but he would later critique idealism strongly). It was also during this time that he discovered Husserl’s phenomenology and his distinct concept of consciousness, which would have an important impact on his philosophical perspective as both an influence and as a critique.

In 1910 he returned to the University of Madrid as a professor of metaphysics, and in that same year he married his wife, Rosa Spottorno. This new position was interrupted for a third trip to Germany in 1911, which was both an opportunity for a honeymoon and to continue his studies in Marburg. Ortega and Spottorno’s first son, whom they named Miguel Alemán, was born during this last extended period abroad in Germany. Miguel’s second name translates as “German,” which shows Ortega’s great interest in the nation, as it would come to serve as a model state for him in many ways. Ortega was firmly focused on his goal to modernize Spain, which he saw as greatly behind many other European nations.

From 1932 until the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, he made a shift away from idealism to emphasize an “I” that is inextricably immersed in circumstances. He developed a new focus for his philosophy: that of historical reason, a position greatly influenced by one of his most admired thinkers, Wilhelm Dilthey. His objective was to develop a philosophy that was neither idealist nor realist.

The rise of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco at the end of the Civil War in 1939 was the main reason for his voluntary exile in Argentina and Portugal until 1945. His return to Spain thereafter was not a peaceful one. He had made political enemies across the spectrum, and, as a result, he struggled to write and teach freely. He decided to continue to travel and lecture elsewhere. During these later years he also received two honorary Doctorates: one from the University of Marburg, and another from the University of Glasgow. Ortega suffered from poor health, especially in the last couple decades of his life, which prevented him from traveling more extensively including for an invitation to teach at Harvard. He did make his first trip to the United States in 1949 when he spoke at a conference in Aspen on Goethe. In 1951 he participated in a conference with Heidegger in Darmstadt. He gave his last lecture in Venice in 1955 before succumbing to stomach and liver cancer.

Ortega was a prolific writer—in total, his works cover about 6,000 pages. Most of these works span from the year 1914, when he published his first book, Meditations on Quixote, to the 1940s, but there were also several important posthumous publications. Ortega cannot be readily classified because he wrote about such a broad range of subjects that included philosophy, history, literary criticism, sociology, and travel writing. He was a philosopher, educator, essayist, theorist, critic, editor, and politician. He wrote on the philosophy of life; human life is central in his thought. Some of the varied topics he explored were the human body, history and its categories, phenomenology, society, politics, the press, and the novel. Always part of a newspaper and magazine family, Ortega was primarily an essayist—for this reason, some label him as being a writer of “philosophical journalism.” One of his main goals was to have a dialogue with his readers.

While he did not claim to adhere to any one philosophical movement, given the important role that history plays in his philosophy, we should certainly not deny the influence of other thinkers. Influences on Ortega include Neo-Kantianism, which he studied in Marburg with Hermann Cohen and Paul Natorp, as well as the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl. Additional crucial influences include Wilhelm Dilthey especially, as well as Gottfried Leibniz, Friedrich Nietzsche, Johann Fichte, Georg Hegel, Franz Brentano, Georg Simmel, Benedetto Croce, R. G. Collingwood, and in his country of Spain, Miguel de Unamuno, Francisco Giner de los Ríos, Joaquín Costa Azorín, Ramiro de Maeztu, and Pío Baroja, to note some key figures.

Ortega himself left a lasting impact on other important Spanish intellectuals, such as Ramón Pérez de Ayala, Eugenio d’Ors, Américo Castro, and Julian Marías. There were several disciples of his, including Eugenio Imaz, José Gaos, Ignacio Ellacuría, Joaquín Xirau, Eduardo Nicol, José Ferrater Mora, María Zambrano, and Antonio Rodríguez Huescar, who also immigrated to the Latin American countries of Mexico, Venezuela, El Salvador, and Argentina, continuing to add to the philosophical landscape abroad.

In Latin America, there were several important thinkers and historical figures directly influenced by Ortega, such as Samuel Ramos and Leopoldo Zea in Mexico, Luis Recasens Siches from Guatemala—and even the Puerto Rican politician Jaime Benítez (1908-2001) wanted his nation to be like an “Orteguian Weimar.”

2. Philosophy of Life

For Ortega, the activity of philosophy is intimately connected to human life, and metaphysics is a central source of study for how human beings address existential concerns. The first and therefore radical reality is the self, living, and all else radiates from this. The task of the philosopher is to study this radical reality. In Ortega’s philosophy, metaphysics is a ‘construction of the world,’ and this construction is done within circumstances. The world is not given to us ready-made; it is an interpretation made within human life. No matter how unrefined or inaccurate our interpretations may be, we must make them. This interpretation is the resolution of the way in which humankind needs to navigate his or her circumstances. This is a problem of absolute insecurity that must be solved. We may not be able to choose all our circumstances, but we are free in our actions, in the choice of possibilities that lie before us—this is what most strikingly makes us different, he says, from animals, plants, or stones. This emphasis on (limited) human freedom and choice is a principal reason why he is often classified as an “existentialist thinker.” Humankind must make his or her world to save themselves and install themselves within it, he argues. And nobody but the sole individual can do this.

Metaphysics consists of individuals working out the radical orientation of their situation, because life is disorientation; life is a problem that needs to be solved. The human individual comes first, as he argues that to understand “what are things,” we need to first understand “what am I.” The radical reality is the life of each individual, which is each individual’s “I” inextricably living within circumstances. This distinction also marks a break with an earlier influence of phenomenology. For Ortega, human reality is not solipsistic, as many critiqued was the case with Husserl’s method (though Husserl did try to respond to this as a misreading of his view). But neither did Ortega fully reject phenomenology, as it continued to resemble his view on how we are our beliefs—a central position elaborated on further ahead.

The individual human life is the fundamental reality in Ortega’s philosophy. There is no absolute reason (or at least that we can know), there is only reason that stems directly from the individual human life. We can never escape our life just like we can never escape our shadow. There is no absolute, objective truth (or at least that we can know), there is just the perspective of the individual human life. This of course raises the critique that it is contradictory to claim that there is no absolute, as that very idea that there are no absolutes is an absolute. However, what Ortega seems to argue is not a denial of the possibility for the existence of objective truths or absolutes, rather just that, at least for the time being, we cannot know anything beyond each of our own perspectives. Moreover, he is not a staunch relativist, as he argues that there is a hierarchy of perspectives. Life, which is always “my life,” what I call my “I,” is a vital activity that also always finds itself in circumstances. We can choose some circumstances, and others we cannot, but we are always ‘an I within circumstances’—hence his central dictum: “I am my self and my circumstance” (Yo soy yo y mi circunstancia). As a very existentialist theme, a pre-determined life is not given to us; what is given is the need to do something and so life is always a ‘having to do something’ within inescapable circumstances. Thus, life is not the self; life is both the self and the circumstance. This is his position of “razón vital,” which is perhaps best translated as “reason from life’s point of view.” Everything we find is found in our individual lives, and the meaning we attach to things depends on what it means in our lives (which here is arguably a more pragmatist rather than existentialist or phenomenological stance). By the mid-1930s, this would be developed further, adding on the importance of narrative reason to better contemplate what it means to be human. This he titled “razón vital e histórica,” or “historical and vital reason.”

Humankind is an entity that makes itself, he argued. Humans are beings that are not-yet-being, as we are constantly engaged in having to navigate through circumstances. He describes this navigation like being lost at sea, or like being shipwrecked, making life a ‘problem that needs to be solved.’ Life is a constant dialogue with our surroundings. Despite this emphasis on individuality, given humankind’s constant place within circumstances, we are also individuals living with others, so to live is to live-with. More specifically, there are two principal ways that we are living-with: in a coetaneous way as a generational group, and in a contemporaneous way in terms of being of the same historical period. Hence Ortega’s dictum: “Humankind has no nature, only history.” “Nature” refers to things, and “history” refers to humankind. Each human being is a biography of time and space; each human being has a personal and generational history. We can understand an individual only through his or her narrative. Life is defined as ‘places and dates’ immersed in systems of beliefs dominant among generations.

Ortega’s metaphysics thus consists of each human being oriented toward the future in radical disorientation; life is a problem that needs to be solved because in every instance we are faced with the need to make choices within certain circumstances. The human radical reality is the need to constantly decide who we are going to be, always within circumstances. Take, for example, an individual “I” in a room; the room is not literally a part of one’s “I,” but “I” am an “I in a room.” The “I in a room” has possibilities of choices of what to do, but in that moment those are limited to that room. He writes: “Let us save ourselves in the world, save ourselves in things” (What is Philosophy?). In every moment we are each confronted with many possibilities of being, and among those various possible selves, we can always find one that is our authentic self, which is one’s vocation. One only truly lives when one’s vocation coincides with their true self. By vocation he is not referring to strictly one’s profession but also to our thoughts, opinions, and convictions. That is why a human life is future-oriented; it is a project, and he often symbolically refers to human beings as an archer trying to hit the bullseye of his or her authentic vocation—if, of course, they are being true to themselves. The human individual is not an “is,” rather they are a becoming and an inheritor of an individual and collective past.

a. The Individual

Ortega argues that to live is to feel lost, yet one who accepts this is already closer to finding their self. An individual’s life is always “my life”; the vital activity of “I” is always within circumstances. We can choose some of those circumstances, but we can never not be in any. In every instant, we must choose what we are going to do, what we are going to be in the next instant, and this decision is not transferable. Life is comprised of two inseparable dimensions, as he describes it. The first is the I and circumstance, and as such, life is a problem. In the second dimension, we realize we must figure out what those circumstances are and try to resolve the problem. The solutions are authentic when the problem is authentic.

Each individual has an important historical element that factors in here because different time periods may have dominant ideas about how to solve problems. History is the investigation, therefore, into human lives to try to reconstruct the drama that is the life of each one of us—he often also uses the metaphor of our swimming as castaways in the world. The vital question historical study needs to inquire into is precisely the things that change a human’s life; it is not about historical variations themselves but rather what brings about that change. So, we need to ask: how, when, and why did life change?

Each individual exists in their own set of circumstances, though some overlap with those in the lives of others, and thus each individual is an effort to realize their individual “I.” Being faced with the constant need to choose means that living brings about a radical insecurity for each individual. An individual is not defined by body and soul, because those are “things”; rather, one is defined by their life. For this reason, he proclaims his famous thesis that ‘humans have no nature, only history.’ Thus, again, this is why history should be the focus in the study of human lives; history is the extended human drama. Human life, as he so often says, is a drama, and thus the individual becomes the “histrion” of their self—“histrion” referring to a “theatrical performer,” the usage of which dates back to the ancient Greeks. In its etymological roots, from the Greek historia, we have in part “narrative,” and from histōr “learned, wise human”—thus, for Ortega, to study and be aware of one’s narrative is the means by which we become learned and wise. As one lacks or ignores this historical knowledge, there is a parallel fall in living authentically, and when this increasingly manifests itself in a group of people, there is a parallel rise of barbarity and primitiveness, he argues. This, as is elaborated further ahead, is precisely what is at work with the revolt of the masses of his time.

For Ortega, the primitive human is overly socialized and lacks individuality. As a very existentialist theme in his philosophy, we live authentically via our individuality. Existentialist philosophers generally share the critique that the focus on the self, on human existence as a lived situation, had been lost in the history of philosophy. On this point Ortega agrees; however, he does not share exactly the critique that, from the birth of modern philosophy, especially from Descartes onward, the increase in a rational and detached focus on the pursuit of objective knowledge was all that detrimental. This is because humanism was also in part a result, because the new science and human reason permitted humankind to recover faith and confidence in itself. Ortega does not deny that there are certain scientific facts that we must live with, but science, he says, “will not save humankind” (Man and Crisis). In other words, scientific studies can lead to scientific facts, but these should not extend beyond science—it is an error of perspective to reach beyond. As is elaborated further ahead, the richest of the different types of perspectives is that which is focused on the individual human life, as this is the radical reality.

We each live with a future-orientation, yet the future is problematic, and this is the paradoxical condition that is human life: in living for the future, all we have is the past to realize that potential. Ortega argues that a prophet is an inverse historian; one narrates to anticipate the future. An individual’s present is the result of all the human past—we must understand human life as such, just as how one cannot understand the last chapter of a novel without having read the content that came before. This makes history supreme, the “superior science,” he argues, in response to the dominance of physics in his time, for understanding the fundamental, radical reality that is the human life. While Ortega believes that Einstein’s discoveries, for example, support his position of perspectivism and how reality can only be understood via perspectives, again his concern is when the sciences reach too far beyond science into the realm of what it means to be a human individual. Moreover, what had been largely forgotten in his time is how we are so fundamentally historical beings. Thus, a lack of historical knowledge results in a dangerous disorientation and is an important symptom of the crisis of his time: the hyper-civilization of savagery and barbarity that he defines as the “revolt or rebellion of the masses.”

b. Society and The Revolt of the Masses

Society, for Ortega, is not fully natural, as its origins are individualist. Society arises out of the memory of a remote past, so it can only be comprehended historically. But it is also the case for Ortega that an individual’s vocation can be realized only within a society. In other words, part of our circumstance is to always be with others in a reciprocal and dynamic relationship—here his views tend more toward an existential phenomenology, as the world we live in is an intersubjective one, as we are each both unique and social selves; we are living in a world of a multitude of unique individuals. Ortega is quite critical of his time period, but he is detailed enough in his critiques to point toward a potential way of resolving them. In fact, Ortega is one of the first writers to detail something resembling the European Union as a possible solution. For example, he writes, “There is now coming for Europeans the time when Europe can convert itself into a national idea” (The Revolt of the Masses). He was quite concerned with the threat of the time for politics to go in either extreme direction to the left or right, resulting from the crisis of the masses.

This served as part of his inspiration for studying in Germany, which he saw in many ways as a model state, right after he finished his Doctorate. Contemplating an ideal future for his country of Spain became of great importance to him at an early age. In 1898, Spain lost its last colonies after losing the Spanish-American War. A group of Spanish intellectuals arose, appropriately called the “Generation of ’98,” to address how to heal the future of their country. A division resulted between those labeled the “Hispanizantes” and the “Europeazantes” (to which Ortega belonged), which looked to “Hispanicizing” or “Europeanizing” Spain, respectively, to looking back to tradition or looking to Europe as a model.

The most famed of his critiques are captured in his best-selling and highly prophetic book The Revolt of the Masses from 1930. One clear way in which he describes the main problem of not only Europe, but really the world over, is to imagine what happens in an elementary school classroom when the teacher leaves, even if just momentarily; the mob of children “breaks loose, kicks up its heels, and goes wild” (The Revolt of the Masses). The mob feels themselves in control of their own destiny, which had been previously aided by the school master, but this does not mean of course that these children suddenly know exactly what to do. The world is acting like these children, and often even worse, as spoiled children who are ignorant of the history behind all that they believe they have a right to, resulting in great disrespect. Without the direction of a select minority, such as the teacher or school master, the world is demoralized. The world is being chaotically taken over by the lowest common denominator: the barbarous mass-human.

This mob he calls “the mass-man.” The mass-man is distinguished from the minority both quantitatively and qualitatively—most important is the latter. While the minority consists of specially qualified individuals, the mass-person is not, and he or she is content with that (there is an influence apparent here from Nietzsche’s distinction between “master” and “slave” moralities, but it is not the same). The mass-man sees him or herself just like everybody else and does not want to change that. The minority makes great demands on themselves because they do not see themselves as superior, yet they are striving to improve themselves, whereas the mass-man does not. Being a minority group requires setting themselves apart from the majority, whereas this is not needed for defining a majority, he argues. So, the distinction here is not about social classes; rather, it refers mostly to mentality. The problem, Ortega argues, is that this is essentially upside-down; the minorities feel mediocre, yet not a part of the mass, and the masses are acting as the superior ones, which is enabling them to replace the minorities. He calls this state a hyper-democracy, and it is for Ortega the great crisis of the time because in the process the masses are crushing that which is different, qualified, and excellent. The result is the sovereignty of the unqualified individual—and this is stronger than ever before in history, though this kind of crisis has happened before.

The masses have a debilitating ignorance of history, which is central to sustaining and advancing a civilization. History is necessary to learn what we need to avoid in the future—“We have a need of history in its entirety, not to fall back into it, but to see if we can escape from it” (The Revolt of the Masses). Civilization is not self-supporting, such as nature is, yet the masses, in their lack of historical consciousness, think this to be the case. It is a rebellion of the masses because they are not accepting their own destiny and, therefore, rebelling against themselves. The result, Ortega fears, is great decay in many areas; there will be a militarization of society, a bureaucratization of life, and a suspension of spontaneous action by the state, for example, which the mass-man believes himself to be. Everyone will be enslaved by the state. He saw this clearly in his nation of Spain, where regional particularism was dominant and demolished select individuality (he develops this theory of his country having become ‘spineless’ in another of his more successful books titled Invertebrate Spain). As is further elaborated ahead, this can also be seen in the art trends of the time, as movements toward greater abstraction were having the effect of minimizing the number of people who could ‘understand it.’ Despite having critiqued the aesthetics of the time, Ortega also thought this could shift the balance from the dominance of the masses and put them ‘back into their appropriate places.’ The arts, then, will help restore the select hierarchy.

c. The Mission of the University

Another part of his answer to this crisis of his times lies in the university: the mission of the university is to teach culture, essentially. By “culture” he was referring to more than just scholarly knowledge; it was about being in society. Universities should aim to teach the “average” person to be a good professional in society. Science, very broadly understood here, has a different mission than the university and not every student should be churned into a “scientist.” This does not mean that science and the university are not connected, it is just to emphasize that not all students are scientists. Ortega recognizes that science is necessary for the progression of society, but it should not be the focus of a university education. For this reason, university professors should be chosen for their teaching skills over their intellectual aptitudes, he argued. Again, students should be groomed to follow the vocation of their authentic self. The self is what one potentially is; life is a project. Therefore, what one needs to know is what helps one realize their personal project (again, this is why ‘vital reason’ is ‘reason from life’s point of view’). Not everybody is aware of what their project is, and it is essential to human life to strive to figure out what that is, and ideally realize it as close to fully as possible—the university can aid in this endeavor. But Ortega was also cognizant of the challenge of this endeavor, as perhaps the ‘right frame of mind, dispositions, moods, or tastes’ cannot be taught.

3. Perspectivism

As humankind is always in the situation of having to respond to a problem, we must know how to deal and live with that problem—and this is precisely the meaning of the Spanish verb “saber,” or “to know” (as in concrete facts): to know what to do with the problems we face. Thus, Ortega’s epistemology can be summarized concisely as follows: the only knowledge possible is that which originates from an individual’s own perspective. Knowledge, he writes, is a “mutual state of assimilation” between a thing and the thinker’s process of thinking. When we confront an object in the world, we are only confronting a fragment of it, and this forces us to try to think about how to complete that object. Therefore, philosophizing is unavoidable in life (for some, at least, he argued), because it is part of this process of trying to complete what is a world of fragments. Further, this forms part of the foundation of his perspectivism: we can never see and thus understand the world from a complete perspective, only our own limited one. Perspective, then, is both a component of reality as well as what we use to organize reality. For example, when we look up at a skyscraper from the street level, we can never see the whole building, only a fragment of it from our limited perspective.

In his book What is Knowledge?, which consists of lectures from 1929-1930, we find some of his initial leanings on idealism (which he would come to increasingly move away from), but even here he is not rejecting realism but rather making it subordinate to idealism. This is because, he argues, the existence of the world can only first be derived from the existence of thought. For the world to exist, thought must exist; existence of the world is secondary to the existence of thought. Idealism, he argues, is the realism of thought. Ultimately, however, Ortega rejects both idealism and realism; neither suffices to explain the radical reality that is the individual human life, the coexistence of selves with things. While science begins with a method, philosophy begins with a problem—and this is what makes philosophy one of the greatest intellectual activities because human life is a problem, and when we become aware of our ‘falling into this absolute abyss of uncertainty,’ we do philosophy. Science may be exact, but it is not sufficient for understanding what it means to be human. Philosophy may be inexact, but it brings us much closer to understanding what it means to be human because it is about contemplating the radical reality that is the life of each one of us. Because humankind constantly confronts problems, this makes philosophy a more natural intellectual task than any science. Thus, “each one knows as much as he [they] has doubted” (What is Knowledge?). Ortega measures “the narrowness or breadth of [their] wit by the scope of [their] capacity to doubt and feel at a loss” (What is Knowledge?).

Therefore, one does not need certainties, argues Ortega; what is needed is a system of certainties that creates security in the face of insecurity. He argues: “the first act of full and incontrovertible knowledge” is the acknowledgement of life as the primordial and radical reality (What is Knowledge?). No one perspective is true nor false (though there may be a pragmatic hierarchy of perspectives); it is affected by time and place. For example, it is not just about a visual field; there are many other fields that can be present and vary by time and place. Time itself can be experienced very differently, such as how Christmas Eve may seem to be the longest night of the year for young children, whereas their birthday party passes much too quickly. A subject informs an object, and vice versa; it is an abstraction to speak of one without the other. “To know,” therefore, is to know what to live with, deal with, abide by, in response to the circumstances we find ourselves in—this is a clear example of the existentialist thinking that can be found in his thought, as he emphasizes that the most important knowledge is the individual self that understands his or her circumstances well enough to know how to live with them, deal with them, and in response form principles to abide by. Science will not suffice to help us in this endeavor. It is only in being clear with our selves that we can better navigate the drama that is the individual human life—again, a very existentialist theme. This does not require being highly educated—as this also runs its own risk of getting lost in scholarship, he urges—and the individual need not look far (though neither does this mean that individuals always make this effort). Part of what makes us human is our imagination; human life then is a work of imagination, as we are the novelists of our selves.

Ortega critiques the philosophy of the mid-nineteenth century until the early twentieth century as being “little more than a theory of knowledge” (What is Philosophy?) that still has not been able to answer the most fundamental question as to what knowledge is, in its complete meaning. He is especially highly critical of positivism. He argues that we must first understand what meaning the verb to know carries within itself before we can consider seriously a theory of knowledge. And just as life is a task, knowing is a task that humans impose on themselves, and it is perhaps an impossible task, but we feel this need to know and impose this task on ourselves because we are aware of our ignorance. This awareness of our ignorance is the focus that an epistemological study should take, Ortega argued.

a. Ideas and Beliefs

An important connection between his metaphysics and his epistemology is his distinction between ideas and beliefs. A “belief,” he argues, is something we maintain without being conscious or aware of it. We do not think about our beliefs; we are inseparably united with them. Only when beliefs start to fail us do we begin to think about them, which leads to them no longer being beliefs, and they become “ideas.” Here we can see an influence of Husserl’s phenomenology in trying to ‘suspend’ habitual beliefs, and Ortega adds, to understand how history is moved by them. We do not question beliefs, because when we do, then they stop being beliefs. In moments of crisis, when we question our beliefs, this means we are thinking about them so instead again they become “ideas.” We look at the world through our ideas, and some of them may become beliefs. The “real world” is a human interpretation, an idea that has established itself as a belief.

When we are left without beliefs, then we are left without a world, and this change then converts into a historical crisis—this is an important connection to his theory on history described further ahead. The human individual is always a coming-from-something and a going-to-something, but in moments of crisis, this duality becomes a conflict. The fifteenth century provides a clear example, as it marked a historical crisis of a coming-from the medieval lifestyle conflicting with a going-to a new ‘modern’ lifestyle. So, in a historical crisis such as this one, there is an antithesis of different modes of the same radical attitude; it is not like the coming-from and going-to of the seasons, like summer into fall. The individual of the fifteenth century was lost, without convictions (especially those stemming from Christianity), and as such, was living without authenticity—just as the individual of his day, he argues. The fifteenth century is a clear example of “the variations in the structure of human life from the drama that is living” (Man and Crisis). There was a crisis then of reason supplanting faith (as was also seen when faith supplanted reason in the shift into the start of the medieval period). In times such as these, as with Ortega’s own, there is a crisis of belief as to ‘who knows best.’

Beliefs are thus connected to their historical context, and as such, historical reason is the best tool for understanding both the ebb and flow of beliefs being shaken up and moments of historical crises. Epochs may be defined by crises of beliefs. Ortega argued that he was living in precisely one of those times, and that it took the form of a “rebellion of the masses.” Beliefs in the form of faith in old enlightenment ideals of confidence in science and progress were failing, and advances in technology were making this harder for people to see, precisely because it puts science to work. Reality is a human reality, so science does not provide us with the reality. Instead, what science provides are some of the problems of reality.

4. Theory of History

Ortega believed that “philosophy of history” was a misnomer and preferred the term “theory” for his lengthy discussions on history, a topic which has central importance in his thought. He objected to many terms, which adds to the difficulty of classifying him (others include objections to being an ‘existentialist’ and even a ‘philosopher’). Much of Ortega’s theory on history is outlined in Man and People, Man and Crisis, History as a System, An Interpretation of Universal History, and Historical Reason. The use of the term “system” in his philosophical writings on history is at times misleading because what he is referring to is a kind of pattern or trend that can be studied, but it is not a teleological vision on history. History is defined by its systems of beliefs. As outlined in the section on ideas and beliefs, we hold ideas because we consciously think about them, and we are our beliefs because we do not consciously think about them. There are certain beliefs that are fundamental and other secondary beliefs that are derived from those. To study human existence, whether it be of an individual, a society, or a historical age, we must outline what this system of beliefs is, because crises in beliefs, when they are brought to awareness and questioned, are what move history on any level (personal, generational, or societal). This system of beliefs has a hierarchized order that can help us understand our own lives, that of others, today, and of the past—and the more of these comparisons we compile, the more accurate will be the result. Changes in history are due largely to changes in beliefs. Part of this stems from his view that in these moments, some of us also become aware of our inauthentic living brought about by accepting prevailing beliefs without question. The activity of philosophy is part of this questioning.

History is of fundamental importance to all his philosophy. Human beings are historical beings. Knowledge must be considered in its historical context; “what is true is what is true now” (History as a System). This again raises the critique of what we can do without any objective, absolute knowledge (and also places him arguably in the pragmatist camp here). But Ortega responds that while science may not provide insight on the human element, vital historical reason can. He argues that we can best understand the human individual through historical reason, and not through logic or science. One of his most well-known dictums is that “humankind has no nature, only history.” For Ortega, “nature” refers to something that is fixed; for example, a stone can never be anything other than a stone. This is not the case with humankind, as life is “not given to us ready-made”; we do find ourselves suddenly in it, but then “we must make it for ourselves,” as “life is a task,” unique to each individual (History as a System). This “thrownness” in the world is another very existentialist theme (for which some debate exists about the chronology of the development of this philosophy between Ortega and Heidegger, especially considering they personally knew and respected each other). A human being is not a “thing”; rather, a human life is a drama, a happening, because we make ourselves as infinitely plastic beings. “Things” are objects of existence, but they do not live as humans do, and each human does so according to their own personal choices in response to the problems we face in navigating our circumstances. “Before us lie the diverse possibilities of being, but behind us lies what we have been. And what we have been acts negatively on what we can be,” he writes, and again this applies to any level of humanity, whether regarding individuals or states (History as a System). Thus, while we cannot know what someone or some collective entity will be, we can know what someone or some collective entity will not be. Those possibilities of being are challenged by the circumstances we find ourselves in, so, “to comprehend anything human, be it personal or collective, one must tell its history” (History as a System). In a general sense, humans are distinct in our possession of the concept of time; the human awareness of the inevitability of death makes this so.

We cannot speak of “progress” in a positive sense in the variable becoming of a human being, because an a priori affirmation of progress toward the better is an error, as it is something that can only be confirmed a posteriori by historical reason. So, by “progress,” Ortega means simply an “accumulation of being, to store up reality” (History as a System). We have each inherited an accumulation of being, which is what further gives history its systematic quality, as he writes: “History is a system, the system of human experiences linked in a single, inexorable chain. Hence nothing can be truly clear in history until everything is clear” (History as a System). Since the ancient Greek period, history and reason had been largely opposed, and Ortega wants to reverse this—hence his use of the term “historical reason.” He is not referring to something extra-historical, but rather something substantive: the reality of the self that is underlying all, and all that has happened to that self. Nothing should be accepted as mere fact, he argues, as facts are fluid interpretations that are themselves also embedded in a historical context, so we must study how they have come about. Even “nature” is still just humankind’s “transitory interpretation” on the things around us (History as a System). As Nietzsche similarly argued, humankind is differentiated from animals because we have a consciousness of our own history and history in general. But again, the idea here is that the past is not really past; as Ortega argues, if we are to speak of some ‘thing’ it must have a presence; it must be present, so the past is active in the present. History tells us who we are through what we have done—only history can tell us this, not the physical sciences, hence again his call for the importance of “historical reason.” The physical sciences study phenomena that are independent, whereas humans have a consciousness of our historicity that is, therefore, not independent from our being.

Through history we try to comprehend the variations that persists in the human spirit, writes Ortega. These hierarchized variations are produced by a “vital sensitivity,” and those variations that are decisive become so through a generation. The theory of generations is fundamental to understanding Ortega’s philosophy on (not of) history, as he argues that previous philosophies on history had focused too much on either the individual or collective, whereas historical life is a coexistence of the two. For Ortega, a generation is divided into groups of fifteen-year increments. Each generation captures a perspective of universal history and carries with it the perspectives that came prior. For each generation, life has two dimensions: first, what was already lived, and second, spontaneity. History can also be understood like cinematography, and with each generation comes a new scene, but it is a film that has not come to an end. We are all always living within a generation and between generations—this is part of the human condition.

The two generations between the ages of thirty to sixty are of particular influence in the movement of history, as they generally represent the most historical activity, he argues. From the ages of thirty to forty-five we tend to find a stage of gestation, creation, and polemic. In the generational group from ages forty-five to sixty, we tend to find a stage of predominance, power, and authority. The first of these two stages prepares one for the next. But Ortega also posits that all historical actuality is primarily comprised of three “todays,” which we can also think of as the family writ large: child, parent, grandparent. Life is not an ‘is’—it is something we must make; it is a task, and each age is a particular task. This is because historical study is not to be concerned with only individual lives, as every life is submerged in a collective life; this is one circumstance, that we are immersed in a set of collective beliefs that form the “spirit of the time.” This is very peculiar, he argues, because unlike individual beliefs that are personally held, collective beliefs that take the form of the “spirit of the time” are essentially held by the anonymous entity that is “society,” and they have vigor regardless of individual acceptance. From the moment we are born we begin absorbing the beliefs of our time. The realization that we are unavoidably assigned to a certain age group, or spirit of the time, and lifestyle, is a melancholic experience that all ‘sensitive’ (philosophically-minded) individuals eventually have, he posits.

Ortega makes an important distinction between being “coeval” or “coetaneous,” and being “contemporary.” The former refers to being of the same age, and the latter refers to being of the same historical time period. The former is that of one’s generation, which is so critical that he argues those of the same generation but different nations are more similar than those of the same nation but different generations. His methodology for studying history is grounded in projecting the structure of generations onto the past, as it is a generation that produces a crisis in beliefs that then leads to change and new beliefs (discussed above). He also defines a generation as a dynamic compromise between the masses and the individual on which history hinges. Every moment of historical reality is the coexistence of generations. If all contemporaries were coetaneous, history would petrify and innovation would be lost, in part because each generation lives their time differently. Each generation, he writes, represents an essential and untransferable piece of historical time. Moreover, each generation also contains all the previous generations, and as such is a perspective on universal history. We are the summary of the past. History intends to discover what human lives have been like, and by human, he is not referring to body or soul, because individuals are not “things,” we are dramas. Because we are thrown into the world, this drama creates a radical insecurity that makes us feel shipwrecked or headed for shipwreck in life. We form interpretations of the circumstances we find ourselves thrown into and then must constantly make decisions based upon those. But we are not alone, of course; to live is to live together, to coexist. Yet it is precisely that reality of coexistence that makes us feel solitude; hence our attempt to avoid this loneliness through love. Ortega’s theory on history is therefore a combination of existential, phenomenological, and historicist elements.

5. Aesthetics

Ortega’s Phenomenology and Art provides a very phenomenological and existentialist philosophy on art. Art is not a gateway into an inner life, into inwardness. When an image is created of inwardness, it then ceases to be inward because inwardness cannot be an object. Thus, what art reveals is what seems to be inwardness through esthetic pleasure. Art is a kind of language that tells us about the execution of this process, but it does not tell us about things themselves. A key example he gives to understand this is the metaphor, which he considers an elementary esthetic object. A metaphor produces a “felt object,” but it is not, strictly speaking, the objects themselves that it includes. Art, he says, is de-creation because like in the example of a metaphor, it creates a new felt object out of essentially the destruction of other objects. There is a connection to Brentano and Husserl here in this experience that consciousness is of a consciousness of an object (though, it has been noted, Ortega ultimately aims to redirect the reduction of Husserl and against pure consciousness to instead promote consciousness from the point of view of life).

In the example of painting, which he considers “the most hermetic of all the arts” (Phenomenology and Art), he further elaborates on the importance of an artist’s view on the occupation itself, of being an “artist.” The occupation one chooses is a very personal and important one, thus style is greatly impacted by how an artist would answer the question as to what it means “to be a painter” (Phenomenology and Art). Art history is not just about changes in styles; it is also about the meaning of art itself. Most important is why a painter paints rather than how a painter paints, he argues (as another very existentialist position).

Ortega’s philosophy on the art of his time is further developed in his essay The Dehumanization of Art. While the focus of his analysis in this text is the art of his time, his objective is to understand and work through some basic characteristics of art in general. As this was published in 1925, the art movements he often refers to are those tending toward abstraction, such as expressionism and cubism. He was quite critical of Picasso, for example, but this may have also been primarily politically motivated. His ultimate judgment is that the art of his time has been “dehumanized” because it is an expression moving further away from the lived experience as it becomes more “modern.” This new art is “objectifying” things; it is objectifying the subjective, as an expression of an observed reality more remote from the lived human reality. After all, the “abstraction” in this art means precisely this, starting with some object in the real world and abstracting it (as opposed to art that is completely non-representational). Art becomes an unreality. In this we find his phenomenological leaning, calling to go back “to the things themselves” in art. This is arguably also part of the general existentialist call to avoid objectifying human individuals.

Still, this can provide insight into his contemporary historical age, and there is value in that—hence his desire to better understand the art of his time, the art that divides the public into the elite few that understand and appreciate it, and the majority who do not understand nor enjoy it. There is also value in how this may be used to ‘put the masses back into their place,’ because only an elite few understand ‘modern art.’ Perhaps this could serve as a test, Ortega argued, by observing how one views a work of abstract art. We can add to our judgments about a person’s place as part of the minority or mass his or her ability to contemplate this art.

6. Philosophy

History, for Ortega, represented the “inconstant and changing,” whereas philosophy represented the “eternal and invariable”—and he called for the two to be united in his approach to philosophical study. History is human history; it is the reality of humankind. As a critic of his time, he also has much to say about the movements in philosophy of his time and in the history of philosophy. To the question, “what is philosophy?” Ortega answers: “it is a thing which is inevitable” (What is Philosophy?). Philosophy cannot be avoided. It is an activity, and in his many writings on the topic, he wants to take this activity itself and submit it to analysis. Philosophy must be de-read vertically, not read horizontally, he urges. Philosophy is philosophizing, and philosophizing is a way of living. Therefore, the basic problem of philosophy that he wants to submit to analysis is to define that way of living, of being, of “our life.”

Ortega’s call for a rebirth of philosophy and his concern over too much reliance on modern science, especially physics, is one of the many reasons why he is often classified into the category of existentialist philosophers. In fact, for Ortega, a philosopher is really a contradistinction from any kind of scientist in their navigation into the unknown, into problems (like other existentialists, he is also fond of the metaphor for life consisting of navigating a ship headed for shipwreck). Philosophy, he says, is a vertical excursion downward. In his discussions on what philosophy is, he makes several contrasts to science. For example, philosophy begins with the admission that the world may be a problem that cannot be solved, whereas the business of science is precisely about trying to solve problems. But he did not solely critique physics, as it was also something that he believed supported his perspectivism, as seen in the relativism discovered by Albert Einstein—but neither is Ortega a strict relativist. While an individual reality is relative to a time and place, each of those moments is an absolute position. Moreover, not all perspectives are equal; errors are committed, and there are hierarchies of perspectives.

The exclusive subject of philosophy is the fundamental being, which he defines as that which is lacking. Philosophy, he says, is self-contained and can be defined as a “science without suppositions,” which is another inheritance from Husserl’s phenomenology (What is Philosophy?). In fact, he takes issue with the term “philosophy” itself; better, perhaps, is to consider it a theory or a theoretic knowledge, he insists. A theory, he argues, is a web of concepts, and concepts represent ‘the content of the mind that can be put into words.’

7. The History of Philosophy

In his unfinished work, The Origin of Philosophy, Ortega outlines a reading of philosophy similar to that of history; it must be studied in its entirety. Just as one cannot only read the last chapter of a novel to understand it, one must read all the chapters that came before. His main objective with this work then is to recreate the origin of philosophy. In the history of philosophy, we find a lot of inadequate philosophy, he argues, but it is part of our human condition to keep thinking, nonetheless. It is part of our human condition to realize that we have not thought everything out adequately. Hence, perhaps The Origin of Philosophy was meant to be unfinished because it cannot be otherwise. Upon the first read, therefore, the history of philosophy is a history of errors. We need only think of what came after the Presocratics, the first on record to try to formalize some ways of philosophical thinking, who then gave birth to the relativism of the Sophists and the skepticism of the Skeptics, as a few examples of what came after in the form primarily of a critique or a reaction against. By revealing the errors of earlier philosophy, Ortega argues, philosophers then create another philosophy in that process. For Ortega to take this focus precisely when he did, working on this text in the mid-1940s, when logical positivism and contemporary analytic philosophers had come to dominate the Anglo-American philosophical landscape, provides just an example of this as “analytic philosophy.” That term came about in part to separate those philosophers from “continental philosophy” (“continental” primarily being in reference to existentialist-like thinkers, such as Ortega—those on the continent of Europe, not the British Isles).

Error, he argues, seems to be more natural than truth. But he does not believe that philosophy is an absolute error; in errors there must be at least the possibility for some element of truth. It is also the case that sometimes when we read philosophy, the opposite happens: we are initially struck by how it seems to resound the “truth.” What we have next, then, is a judgment about how ‘such and such philosophy’ has merit and another does not. But each philosophy, he argues, contains elements of the others as “necessary steps in a dialectical series” (The Origin of Philosophy). The philosophical past, therefore, is both an accumulation of errors and truths. He says: “our present philosophy is in great part the current resuscitation of all the yesterdays of philosophy” (The Origin of Philosophy). Philosophy is a vertical excursion down, because it is built upon philosophical predecessors, and as such, continues to function in and influence the present. When we think about the past, that brings it into the present; in other words, thinking about the past makes it more than just “in the past.” Again, he shares with Nietzsche this distinction between humankind and animals in how we possess the past and are more than just consequences of it; we are conscious of our past. We are also distinct in how we cannot possess the future, though we strive very hard to—modern science is very focused on this and working to improve our chances at prediction. The first philosopher, Thales, is given that title for being the first on record that we know of to start to think for himself and move away from mythological explanation, as famously demonstrated by how he predicted a solar eclipse using what we would define as a kind of primitive science. In being able to predict more of the future, one can thus ‘eternalize oneself’ more. In this process one has also obtained a greater possession of the past. “The dawn of historical reason,” as he refers to it, will arrive when that possession of the past has reached an unparalleled level of passion, urgency, and comprehension. Just as history broadly moves with crises of beliefs, this applies very explicitly to philosophy (as it is also the best way to contemplate the human lived situation). This also relates to his perspectivism and to the notion of hierarchies that are very much pragmatically founded. For Ortega, examples of particularly moving moments in the history of philosophy come from these great shifts in philosophical beliefs, such as those from the period of ancient Greece and from Descartes especially. For Ortega, the three most crucial belief positions in philosophy to examine via its history are realism, idealism, and skepticism. Ortega’s hope was that this would all, ideally, come closer to a full circle with the next belief position: that of his “razón vital e histórica,” or “historical and vital reason.”

Despite the challenges in understanding the wide breadth of writings of José Ortega y Gasset, perhaps it serves us best to read him in the context of his own methodology of historical and vital reason—as an individual, a man of his times, searching for nuggets of insight among a history of errors.

8. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

- Ortega’s Obras Completas are available digitally.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Obras Completas Vols. I-VI. Spain: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, 2017.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Obras Completas Vols. VII-X (posthumous works). Spain: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, 2017.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Meditations on Quixote. New York: W.W. Norton, 1961.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. The Dehumanization of Art and Other Essays on Art, Culture, and Literature. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Phenomenology and Art. New York: W.W. Norton, 1975.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Historical Reason. New York: W.W. Norton, 1984.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Toward a Philosophy of History. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. History as a System and other Essays Toward a Philosophy of History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1961.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. An Interpretation of Universal History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1973.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. The Revolt of the Masses. New York: W.W. Norton, 1932.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. What is Philosophy? New York: W.W. Norton, 1960.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. The Origin of Philosophy. New York: W.W. Norton, 1967.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Man and Crisis. New York: W.W. Norton, 1958.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Man and People. New York: W.W. Norton, 1957.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Meditations on Hunting. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Psychological Investigations. New York: W.W. Norton, 1987.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Mission of the University. New York: W.W. Norton, 1966.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. The Modern Theme. New York: W.W. Norton, 1933.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. On Love: Aspects of a Single Theme. Cleveland: The World Publishing Company, 1957.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Some Lessons in Metaphysics. New York: W.W. Norton, 1969.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. What is Knowledge? New York: Suny Press, 2001.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Concord and Liberty. New York: W.W. Norton, 1946.

- Ortega y Gasset, José. Invertebrate Spain. New York: Howard Fertig, 1921.

b. Secondary Sources

- Blas González, Pedro. Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega y Gasset’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. St. Paul: Paragon House, 2011.

- Díaz, Janet Winecoff. The Major Theme of Existentialism in the Work of Jose Ortega y Gasset. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1970.

- Dobson, Andrew. An Introduction to the Politics and Philosophy of José Ortega y Gasset. Cambridge: University Press, 1989.

- Ferrater Mora, José. José Ortega y Gasset: An Outline of His Philosophy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1957.

- Ferrater Mora, José. Three Spanish Philosophers: Unamuno, Ortega, and Ferrater Mora. New York: State University of New York Press, 2003.

- Graham, John T. A Pragmatist Philosophy of Life in Ortega y Gasset. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1994.

- Graham, John T. The Social Thought of Ortega y Gasset: A Systematic Synthesis in Postmodernism and Interdisciplinarity. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001.

- Graham, John T. Theory of History in Ortega y Gasset: The Dawn of Historical Reason. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997.

- Gray, Rockwell. The Imperative of Modernity: An Intellectual Biography of José Ortega y Gasset. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

- Holmes, Oliver W. José Ortega y Gasset. A Philosophy of Man, Society, and History. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1971.

- Huéscar, Antonio Rodríguez y Jorge García-Gómez. José Ortega y Gasset’s Metaphysical Innovation: A Critique and Overcoming of Idealism. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

- McClintock, Robert. Man and His Circumstances: Ortega as Educator. New York: Teachers College Press, 1971.

- Mermall, Thomas. The Rhetoric of Humanism: Spanish Culture after Ortega y Gasset. New York: Bilingual Press, 1976.

- Raley, Harold C. José Ortega y Gasset: Philosopher of European Unity. University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1971.

- Sánchez Villaseñor, José. José Ortega y Gasset, Existentialist: A Critical Study of his Thought and his Sources. Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1949.

- Silver, Philip W. Ortega as Phenomenologist: The Genesis of Meditations on Quixote, New York: Columbia University Press, 1978.

- Sobrino, Oswald. Freedom and Circumstance: Philosophy in Ortega y Gasset, Charleston: Logon, 2011.

Author Information

Marnie Binder

Email: marnie.binder@csus.edu

California State University, Sacramento

U. S. A.