Models

The word “model” is highly ambiguous, and there is no uniform terminology used by either scientists or philosophers. Here, a model is considered to be a representation of some object, behavior, or system that one wants to understand. This article presents the most common type of models found in science as well as the different relations—traditionally called “analogies”—between models and between a given model and its subject. Although once considered merely heuristic devices, they are now seen as indispensable to modern science. There are many different types of models used across the scientific disciplines, although there is no uniform terminology to classify them. The most familiar are physical models such as scale replicas of bridges or airplanes. These, like all models, are used because of their “analogies” to the subjects of the models. A scale model airplane has a structural similarity or “material analogy” to the full scale version. This correspondence allows engineers to infer dynamic properties of the airplane based on wind tunnel experiments on the replica. Physical models also include abstract representations which often include idealizations such as frictionless planes and point masses. Another, but completely different type of model, is constituted by sets of equations. These mathematical models were not always deemed legitimate models by philosophers. Model-to-subject and model-to-model relations are described using several different types of analogies: positive, negative, neutral, material, and formal.

Like unobservable entities, models have been the subject of debate between scientific realists and antirealists. One’s position often depends on what one considers the truth-bearers in science to be. Those who take fundamental laws and/or theories to be true believe that models are true in inverse proportion to the degree of idealization used. Highly idealized models would therefore be (in some sense) less true. Others take models to be true only insofar as they describe the behavior of empirically observable systems. This empiricism leads some to believe that models built from the bottom-up are realistic, while those derived in a top-down manner from abstract laws are not.

Models also play a key role in the semantic view of theories. What counts as a model on this approach, however, is more closely related to the sense of models in mathematical logic than in science itself.

Table of Contents

- Models in Science

- Physical Models

- Mathematical Models

- State Spaces

- Models and Realism

- Models and the Semantic View of Theories

- References and Further Reading

1. Models in Science

The word “model” is highly ambiguous, and there is no uniform terminology used by either scientists or philosophers. This article presents the most common type of models found in science as well as the different relations—traditionally called “analogies”—between models and between a given model and its subject. For most of the 20th century, the use of models in science was a neglected topic in philosophy. Far more attention was given to the nature of scientific theories and laws. Except for a few philosophers in the 1960’s, Mary Hesse in particular, most did not think the topic was particularly important. The philosophically interesting parts of science were thought to lie elsewhere. As a result, few articles on models were published in twenty-five years following Hesse’s (1966). [These include (Redhead, 1980) and (Wimsatt, 1987), and parts of (Bunge, 1973) and (Cartwright, 1983.] The situation is now quite different. As philosophers of science have come to pay greater attention to actual scientific practice, the use of models has become an import area of philosophical analysis.

2. Physical Models

One familiar type of model is the physical model: a material, pictorial, or analogical representation of (at least some part of) an actual system. “Physical” here is not meant to convey an ontological claim. As we shall see, some physical models are material objects; others are not. Hesse classifies many of these as either replicas or analogue models. Examples of the former are scale models used in wind tunnel experiments. There is what she calls a “material analogy” between the model and its subject, that is, a pretheoretic similarity in how their observable properties are related. Replicas are often used when the laws governing the subject of the model are either unknown or too computationally complex to derive predictions. When a material analogy is present, one assumes that a “formal analogy” also exists between the subject and the model. In a formal analogy, the same laws govern the relevant parts of both the subject and model.

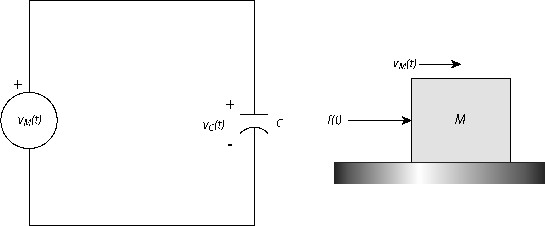

Analogue models, in contrast, have a formal analogy with the subject of the model but no material analogy. In other words, the same laws govern both the subject and the model, although the two are physically quite different. For example, ping-pong balls blowing around in a box (like those used in some state lotteries) constitute an analogue model for an ideal gas. Some analogue models were important before the age of digital computers when simple electric circuits were used as analogues of mechanical systems. Consider a mass M on a frictionless plane that is subject to a time varying force f(t) (Figure 1). This system can be simulated by a circuit with a capacitor C and a time varying voltage source v(t). The voltage across C at time t corresponds to the velocity of M.

Figure 1: Analogue Machine

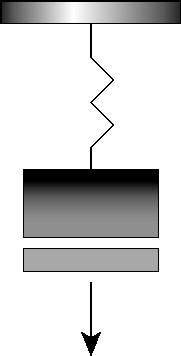

Today engineers and physicists are more familiar with simplifying models. These are constructed by abstracting away properties and relations that exist in the subject. Here we find the usual zoo of physical idealizations: frictionless planes, perfectly elastic bodies, point masses, and so forth. Consider a textbook mass-spring system with only one degree of freedom (that is, the spring oscillates perfectly along one dimension) shown in Figure 2. This particular system is physically possible, but nonactual. Real springs always wobble just a bit. If by chance a spring did oscillate in one dimension for some time, the event would be unlikely but would not violate any physical laws. Frictionless planes, on the other hand, are nonphysical rather than merely nonactual.

Figure 2: Physical Water Drop Model

Simplifying models provide a context for Hesse’s other relations known as positive, negative, and neutral analogies. Positive analogies are the ways in which the subject and model are alike—the properties and relations they share. Negative analogies occur when there is a mismatch between the two. The idealizations mentioned in the previous paragraph are negatively analogous to their real-world subjects. In a scale-model airplane (a replica), the length of the wing relative to the length of the tail is a positively analogous since the ratio is the same in the subject and the model. The wood used to make the model is negatively analogous since the real airplane would use different materials. Neutral analogies are relations that are in fact either positive or negative, but it is not yet known which. The number of neutral analogies is inversely related to our knowledge of the model and its subject. One uses a physical model with strong, positive analogies in order to probe its neutral analogies for more information. Ideally, all neutral analogies will be sorted into either positive or negative. The early success of the Bohr model of the atom showed that it had positive analogies to real hydrogen atoms. In Hesse’s terms, the neutral analogies proved to be negative when the model was applied to atoms with more than one electron.

The use of “analogy” in this regard has declined somewhat in recent years. “Idealization” has replaced “negative analogy” when these simplifications are built into physical models from the start. The degree to which a model has positive analogies is more typically described by how “realistic” the model is. One might also use the notion of “approximate truth”—a term long recognized as more suggestive than precise. The rough idea is that more realistic models—those with stronger positive analogies—contain more truth than others. “Negative analogy” contains an ambiguity. Some are used at the beginning of the model-building process. The modeler recognizes the false properties for what they are and uses them for a specific purpose—usually to simplify the mathematics. Other negative analogies, known as “artifacts,” are unintended consequences of idealizations, data collection, research methods, and limitations of the medium used to construct the model. Some artifacts are benign and obvious. Consider the wooden models of molecules used in high school chemistry classes. Three balls held together by sticks can represent a water molecule, but the color of the balls is an artifact. (As the early moderns were fond of pointing out, atoms are colorless.) Other artifacts are produced by measuring devices. It is impossible, for example, to fully shield an oscilloscope from the periodic signal produced by its AC current source. This produces a periodic component in the output signal not present in the source itself.

The heavy emphasis here on models in the physical sciences has more to do with the interests of philosophers than scientific practice. Physical models are used throughout the sciences, from immunoglobulin models of allergic reactions to macroeconomic models of the business cycle.

3. Mathematical Models

Philosophers have generally taken physical models as paradigm cases of scientific models. In many branches of science, however, mathematical models play a far more important role. There are many examples, especially in dynamics. Equation (1) below is an ordinary differential equation representing the motion of a frictionless pendulum. [θ is the angle of the string from vertical, l is the length of the string, and g is the acceleration due to gravity. The two dots in the first term stand for the second derivative with respect to time.] Even when sets of equations have clearly been used “to model” some behavior of a system, philosophers were often unwilling to take these as legitimate models. The difference is driven in part by greater familiarity with models in mathematical logic. In the logician’s realm, a model satisfies a set of axioms; the axioms themselves are not models. To philosophers, equations look like axioms. Referring to a set of equations as “a model” then sounds like a category mistake.

(1)

This attitude was eroded in part by the central role mathematical models played in the development of chaos theory. The 1980s saw a deluge of scientific articles with equations governing nonlinear systems as well as the state spaces that represented their evolution over time (see section 4). Physical models, on the other hand, were often bypassed altogether. This made it far more difficult to dismiss “mathematical model” as a scientist’s misnomer. It soon became apparent that all of the issues regarding idealizations, confirmation, and construction of physical models had mathematical counterparts.

Consider the physical model of the electric circuit in Figure 1. A common idealization is to stipulate that the circuit has no resistance. When we look to the associated differential equations—a mathematical model—there is a corresponding simplification, in this case the elimination of an algebraic term that represented the resistance of the wire. Unlike this example, simplification is often more than a mere convenience. The governing equations for many types of phenomena are intractable as they stand. Simplifications are needed to bridge the computational gap between the laws and phenomena they describe. In the old (pre-1926) quantum theory, for example, it was common to run across a Hamiltonian (an important type of function in physics that expresses the total energy of the system) that blocked the usual mathematical techniques—for example, separation of variables. Instead, a perturbation parameter λ was used to convert the problematic Hamiltonian ![]() into a power series such as in equation (2) below. [I, θ are classical action-angle variables. See any text on classical mechanics for more on this method.] Once in this form, one may generate an approximate solution for

into a power series such as in equation (2) below. [I, θ are classical action-angle variables. See any text on classical mechanics for more on this method.] Once in this form, one may generate an approximate solution for ![]() to an arbitrary degree of precision by keeping a finite number of terms and discarding the rest. This is sometimes called a “mediating mathematical model” (Morton 1993) since it operates, in a sense, between the intractable Hamiltonian and the phenomenon it is thought to describe.

to an arbitrary degree of precision by keeping a finite number of terms and discarding the rest. This is sometimes called a “mediating mathematical model” (Morton 1993) since it operates, in a sense, between the intractable Hamiltonian and the phenomenon it is thought to describe.

(2)

4. State Spaces

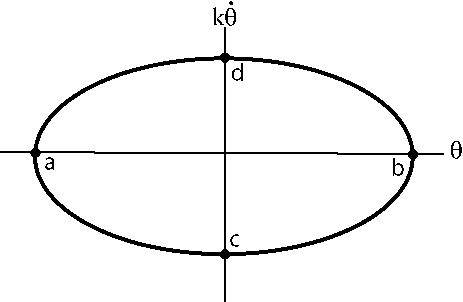

State spaces have received scant attention in the philosophical literature until recently. They are often used in tandem with a mathematical model as a means for representing the possible states of a system and its evolution. The “system” is often a physical model, but might also be a real-world phenomenon essentially free of idealizations. Figure 3 is the state space associate with equation (1), the mathematical model for an ideal (frictionless) pendulum. Since θ represents the angle of the string, a,b correspond to the two highest points of deflection.  represents velocity. [The coefficient

represents velocity. [The coefficient ![]() .] Hence c,d are the points at which the pendulum is moving the fastest.

.] Hence c,d are the points at which the pendulum is moving the fastest.

Figure 3: State Space for Ideal Pendulum

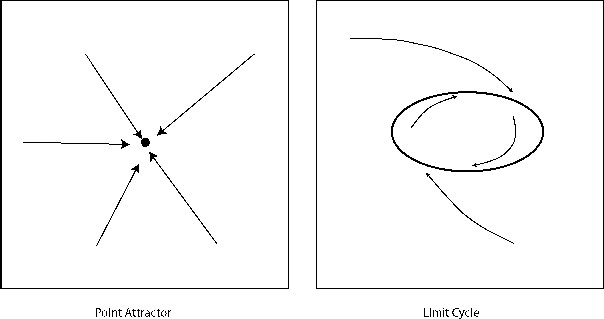

State spaces take a variety of forms. Quantum mechanics uses a Hilbert space to represent the state governed by Schrödinger’s equation. The space itself might have an infinite number of dimensions with a vector representing an individual state. The ordinary differential equations used in dynamics require many-dimensional phase spaces. Points represent the system states in these (usually Euclidean) spaces. As the state evolves over time, it carves a trajectory through the space. Every point belongs to some possible trajectory that represents the system’s actual or possible evolution. A phase space together with a set of trajectories forms a phase portrait (Figure 4). Since the full phase portrait cannot be captured in a diagram, only a handful of possible trajectories are shown in textbook illustrations. If the system allows for dissipation (for example friction), attractors can develop in the associated phase portrait. As the name implies, an attractor is a set of points toward which neighboring trajectories flow, though the points themselves possess no actual attractive force. The center of Figure 4a, known as a point attractor, might represent a marble coming to rest at the bottom of a bowl. Simple periodic motion, like a clock pendulum, produces limit cycles, attracting sets forming closed curves in phase space (Figure 4b).

Figure 4: Sample Phase Portraits

Let us consider a very simple system—a leaky faucet—that illustrates the use of each type of model mentioned. Researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, believed that the time between drops does not change randomly over time, but instead has an underlying dynamical structure (Martien 1985). In other words, one drip interval causally influences the next. In order to explore this hypothesis, a simplified physical model for a drop of water was developed (the one shown above in Figure 2). They believed that a water drop is roughly like a one-dimensional, oscillating mass on a spring. Part of the mass detaches when the spring extends to a critical point. The amount of mass that detaches depends on the velocity of the block when it reaches this point.

The mathematical model (3) for this system is relatively simple. y is the vertical position of the drop, v is its velocity, m is its mass prior to detachment, and Δm is the amount of mass that detaches (k, b, and c are constants). When this model is simulated on a computer, the resulting phase portrait is very similar to the one that was reconstructed from the data in the lab. Although this qualitative agreement is too weak to completely vindicate these models of the dripping faucet, it does provide a small degree confirmation.

(3)

Going back to the physical model, there are two clear idealizations/negative analogies. First, of course, is that water drops are not shaped like rigid blocks. Second, the mass-spring model only oscillates along one axis. Real liquids are not constrained in this way. However, these idealization allow for a far simpler mathematical model to be used than one would need for a realistic fluid. (Without these idealizations, (3) would have to be replaced by a difficult partial differential equation.) In addition, Peter Smith has argued that this mathematical tractability came with a steep price, namely, an unrecognized artifact (1998). The problem is that the state space for this particular system contains a “strange attractor” with a fractal structure, a geometrical structure far more complex than the attractors in Figure 4. Smith argues that the infinitely intricate structure of this attractor is an artifact of the mathematics used to describe the evolution of the system. If more realistic physical and mathematical models were used, this negative analogy would likewise disappear.

5. Models and Realism

One of the perennial debates in the philosophy of science has to do with realism. What aspects of science—if any—truly represent the real world? Which devices, on the other hand, are merely heuristic? Antirealists hold that some parts of the scientific enterprise—laws, unobservable entities, and so forth—do not correspond to anything in reality. (Some, like van Fraassen (1980), would say that if by chance the abstract terms used by scientists did denote something real, we have no way of knowing it.) Scientific realists argue that the successful use of these devices shows that they are, at least in part, truly describing the real world. Let’s now consider what role models have played in this debate.

Whether models should be taken realistically depends on what one takes the truth-bearers in science to be. Some hold that foundational, scientific truths are contained either in mature theories or their fundamental laws. If so, then idealized models are simply false. The argument for this is straightforward (Achinstein 1965). Let’s say that theory T describes a system S in terms of properties p1, p2, and p3. As we have seen, simplified models either modify or ignore some of the properties found in more fundamental theories. Say that a physical model M describes S in terms of p1 and p4. If so, then T describes S in one way; M describes S in a logically incompatible way. The simplifying assumptions needed to build a useful model contradict the claims of the governing theory. Hence, if T is true, M is false.

In contrast, Nancy Cartwright has long argued that abstract laws, no matter how “fundamental” to our understanding of nature, are not literally true. In her earlier work (1983), she argued that it is not models that are highly idealized, but rather the laws themselves. Abstract laws are useful for organizing scientific knowledge, but are not literally true when applied to concrete systems. They are “true,” she argues, only insofar as they correctly describe simplified physical models (or “simulacra”). Fundamental laws are true-of-the-model, not true simpliciter. The idea is something like being true-in-a-novel. The claim “The beast that terrorized the island of Amity in 1975 was a squid” is false-in-the-novel Jaws. Similarly, Newton’s second law of motion plus universal gravitation are only true-in-Newtonian-particle-models.

For most scientific realists, whether physical models are “true” or “real” is not a simple yes-or-no question. Most would point out that even idealizations like the frictionless plane are not simply false. For two blocks of iron sliding past each other, neglecting friction is a poor approximation. For skis sliding over an icy slope, it is much better. In other words, negative analogies come in degrees. If the idealizations are negligible, we may properly say that a physical model is realistic.

Scientific realists have not always held similar views about mathematical models. Textbook model building in the physical sciences often follows a “top-down” approach: start with general laws and first principles and then work toward the specifics of the phenomenon of interest. Dynamics texts are filled with models that can serve as the foundation for a more detailed mathematical treatment (for example, an ideal damped pendulum or a point particle moving in a central field). Philosophers have paid much less attention to models constructed from the bottom-up, that is, models that begin with the data rather than theory. What little attention bottom-up modeling did receive in the older modeling literature was almost entirely negative. Conventional wisdom seemed to be that phenomenological laws and curve-fitting methods were devices researchers sometimes had to stoop to in order to get a project off the ground. They were not considered models, but rather “mathematical hypotheses designed to fit experimental data” (Hesse 1967, 38). According to Ernan McMullin, sometimes physicists—and other scientists presumably—simply want a function that summarizes their observations (1967, 390-391). Curve-fitting and phenomenological laws do just that. The question of realism is avoided by denying the legitimacy of bottom-up mathematical models.

In her broad attack on “theory-driven” philosophy of science, Cartwright has recently defended a nearly opposite view (1999). She argues that top-down mathematical models are not realistic, but bottom-up models are. Once again, this verdict follows from a more general thesis about the truth-bearers in science. Cartwright is an antirealist about fundamental laws and abstract theories which, she claims, serve only to systematize scientific knowledge. Since top-down mathematical models use these laws as first principles from which to begin, they cannot possibly represent real systems. Bottom-up models, on the other hand, are not derived from covering laws. They are instead tied to experimental knowledge of particular systems. Unlike fundamental theories and their associated top-down models, bottom-up models are designed to represent actual objects and their behavior. It is this grounding in empirical knowledge that allows these kinds of mathematical models to be the primary device in science for representing real-world systems.

6. Models and the Semantic View of Theories

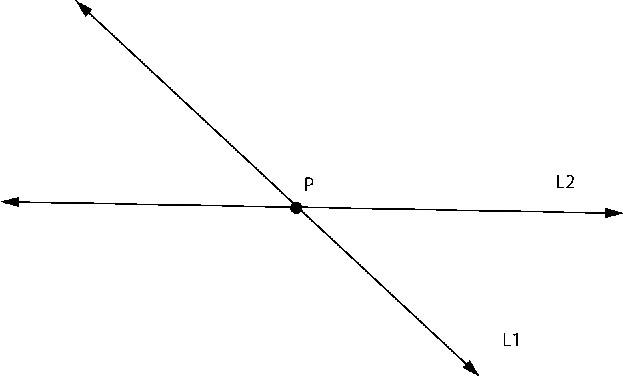

This typology of models and their properties has been developed with an eye toward scientific practice. Within the philosophy of science itself, models have also played a central role in understanding the nature of scientific theories. For most of the 20th century, philosophers considered theories to be special sets of sentences. Theories on this so-called “syntactic view” are linguistic entities. The meaning of the theory is contained in the sentences that constitute it, roughly the same way the meaning of this article is contained in these sentences. The semantic view, in contrast, uses the model-theoretic language of mathematical logic. In broad terms, a theory just is a family of models. The theory/model distinction collapses. Using the terminology we have already defined, a model in this sense might be an idealized physical model, an existing system in nature, or even a state space. The semantic content of a theory, on this view, is found in a family of models rather than in the sentences that describe them. If a given theory were axiomatized—a rare occurrence—one could think of these models as those entities for which the axioms are true. To take a toy example, say T1 is a theory whose sole axiom is “for any two lines, at most one point lies on both.” Figure 5 is one model that constitutes T1:

Figure 5: A Model of Theory T1

A model for ideal gases would be a physical model of dilute, perfectly elastic atoms in a closed container with an ordered set of parameters P, V, m, M, T> that satisfies the equation . (Respectively, pressure, volume, mass of the gases, molecular weight of the molecules, and temperature. R is a constant). In fact two different sets of parameters P1, V1, m1, M1, T1> and P2, V2, m1, M1, T2> constitute two separate models in the same family.

Some advocates of the semantic view claim that the use of the term “model” is similar in science and in logic (van Fraassen, 1980). This similarity has been one of the motivating forces behind this particular understanding of scientific theories. Given the distinctions made in previous sections of this article, this similarity seems to be questionable.

First, many things that would count as a model on the semantic view, for example the geometric diagram in Figure 5, are not physical models, mathematical models, or state spaces. In what sense, one wonders, are they scientific models? Moreover, a model on the semantic view might be an existing physical system. For example, Jupiter and its moons would constitute another model of Newton’s laws of motion plus universal gravitation. This blurs the distinction between the model and its subject. One may use a physical and/or mathematical model to study celestial bodies, but such entities are not themselves models. The scientist’s use of the term is not this broad.

Second, as we have already seen, sets of equations often constitute mathematical models. In contrast, laws and equations on the semantic approach are said to describe and classify models, but are never themselves taken to be models. Their relation is satisfaction, not identity.

Some time before the semantic view became popular, Hesse issued what still seems to be the correct verdict: “[M]ost uses of ‘model’ in science do carry over from logic the idea of interpretation of a deductive system,” however, “most writers on models in the sciences agree that there is little else in common between the scientist’s and the logician’s use of the term, either in the nature of the entities referred to or in the purpose for which they are used” (1967, 354).

7. References and Further Reading

- Achinstein, P. “Theoretical Models.” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 16 (1965): 102-120.

- Bunge, M. Method, Model and Matter. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1973.

- Cartwright, N. How the Laws of Physics Lie. New York: Clarendon Press, 1983.

- Cartwright, N. The Dappled World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Hesse, M. Models and Analogies in Science. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1966.

- Hesse, M. “Models and Analogy in Science.” The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1967.

- McMullin, E. “What do Physical Models Tell Us?” Logic, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science III. Eds. B. van Rootselaar and J. F. Staal. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing, 1967: 385-396.

- Morrison, M. and M. Morgan, eds. Models as Mediators. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Morton, A. “Mathematical Models: Questions of Trustworthiness.” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 44 (1993): 659-674.

- Morton, A. and M. Suàrez. “Kinds of Models.” Model Validation in Hydrological Science. Eds. P. Bates and M. Anderson. New York: John Wiley Press, 2001.

- Redhead, M. “Models in Physics.” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 31 (1980): 154-163.

- Smith, P. Explaining Chaos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Van Fraassen, B. The Scientific Image. New York: Clarendon Press, 1980.

- Wimsatt, W. “False Models as Means to Truer Theories.” Neutral Models in Biology. Eds. M. Nitecki and A. Hoffmann. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Author Information

Jeffrey Koperski

Email: koperski@svsu.edu

Saginaw Valley State University

U. S. A.