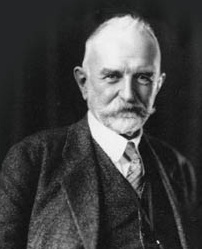

George Herbert Mead (1863—1931)

George Herbert Mead is a major figure in the history of American philosophy, one of the founders of Pragmatism along with Peirce, James, Tufts, and Dewey. He published numerous papers during his lifetime and, following his death, several of his students produced four books in his name from Mead’s unpublished (and even unfinished) notes and manuscripts, from students’ notes, and from stenographic records of some of his courses at the University of Chicago. Through his teaching, writing, and posthumous publications, Mead has exercised a significant influence in 20th century social theory, among both philosophers and social scientists. In particular, Mead’s theory of the emergence of mind and self out of the social process of significant communication has become the foundation of the symbolic interactionist school of sociology and social psychology. In addition to his well- known and widely appreciated social philosophy, Mead’s thought includes significant contributions to the philosophy of nature, the philosophy of science, philosophical anthropology, the philosophy of history, and process philosophy. Both John Dewey and Alfred North Whitehead considered Mead a thinker of the highest order.

George Herbert Mead is a major figure in the history of American philosophy, one of the founders of Pragmatism along with Peirce, James, Tufts, and Dewey. He published numerous papers during his lifetime and, following his death, several of his students produced four books in his name from Mead’s unpublished (and even unfinished) notes and manuscripts, from students’ notes, and from stenographic records of some of his courses at the University of Chicago. Through his teaching, writing, and posthumous publications, Mead has exercised a significant influence in 20th century social theory, among both philosophers and social scientists. In particular, Mead’s theory of the emergence of mind and self out of the social process of significant communication has become the foundation of the symbolic interactionist school of sociology and social psychology. In addition to his well- known and widely appreciated social philosophy, Mead’s thought includes significant contributions to the philosophy of nature, the philosophy of science, philosophical anthropology, the philosophy of history, and process philosophy. Both John Dewey and Alfred North Whitehead considered Mead a thinker of the highest order.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Writings

- Social Theory

- Communication and Mind

- Action

- Self and Other

- The Temporal Structure of Human Existence

- Perception and Reflection: Mead’s Theory of Perspectives

- Philosophy of History

- The Nature of History

- History and Self-Consciousness

- History and the Idea of the Future

- References and Further Reading

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

1. Life

George Herbert Mead was born in South Hadley, Massachusetts, on February 27, 1863, and he died in Chicago, Illinois, on April 26, 1931. He was the second child of Hiram Mead (d. 1881), a Congregationalist minister and pastor of the South Hadley Congregational Church, and Elizabeth Storrs Billings (1832-1917). George Herbert’s older sister, Alice, was born in 1859. In 1870, the family moved to Oberlin, Ohio, where Hiram Mead became professor of homiletics at the Oberlin Theological Seminary, a position he held until his death in 1881. After her husband’s death, Elizabeth Storrs Billings Mead taught for two years at Oberlin College and subsequently, from 1890 to 1900, served as president of Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts.

George Herbert Mead entered Oberlin College in 1879 at the age of sixteen and graduated with a BA degree in 1883. While at Oberlin, Mead and his best friend, Henry Northrup Castle, became enthusiastic students of literature, poetry, and history, and staunch opponents of supernaturalism. In literature, Mead was especially interested in Wordsworth, Shelley, Carlyle, Shakespeare, Keats, and Milton; and in history, he concentrated on the writings of Macauley, Buckle, and Motley. Mead published an article on Charles Lamb in the 1882-3 issue of the Oberlin Review (15-16).

Upon graduating from Oberlin in 1883, Mead took a grade school teaching job, which, however, lasted only four months. Mead was let go because of the way in which he handled discipline problems: he would simply dismiss uninterested and disruptive students from his class and send them home.

From the end of 1883 through the summer of 1887, Mead was a surveyor with the Wisconsin Central Rail Road Company. He worked on the project that resulted in the eleven- hundred mile railroad line that ran from Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, and which connected there with the Canadian Pacific railroad line.

Mead earned his MA degree in philosophy at Harvard University during the 1887-1888 academic year. While majoring in philosophy, he also studied psychology, Greek, Latin, German, and French. Among his philosophy professors were George H. Palmer (1842-1933) and Josiah Royce (1855-1916). During this time, Mead was most influenced by Royce’s Romanticism and idealism.

Since Mead was later to become one of the major figures in the American Pragmatist movement, it is interesting that, while at Harvard, he did not study under William James (1842-1910) (although he lived in James’s home as tutor to the James children).

In the summer of 1888, Mead’s friend, Henry Castle and his sister, Helen, had traveled to Europe and had settled temporarily in Leipzig, Germany. Later, in the early fall of 1888, Mead, too, went to Leipzig in order to pursue a Ph.D. degree in philosophy and physiological psychology. During the 1888-1889 academic year at the University of Leipzig, Mead became strongly interested in Darwinism and studied with Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920) and G. Stanley Hall (1844-1924) (two major founders of experimental psychology). On Hall’s recommendation, Mead transferred to the University of Berlin in the spring of 1889, where he concentrated on the study of physiological psychology and economic theory.

While Mead and his friends, the Castles, were staying in Leipzig, a romance between Mead and Helen Castle developed, and they were subsequently married in Berlin on October 1, 1891. Prior to George and Helen’s marriage, Henry Castle had married Frieda Stechner of Leipzig, and Henry and his bride had returned to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Henry continued his studies in law at Harvard.

Mead’s work on his Ph.D. degree was interrupted in the spring of 1891 by the offer of an instructorship in philosophy and psychology at the University of Michigan. This was to replace James Hayden Tufts (1862-1942), who was leaving Michigan in order to complete his Ph.D. degree at the University of Freiburg. Mead took the job and never thereafter resumed his own Ph.D. studies

Mead worked at the University of Michigan from the fall of 1891 through the spring of 1894. He taught both philosophy and psychology. At Michigan, he became acquainted with and influenced by the work of sociologist Charles Horton Cooley (1864-1929), psychologist Alfred Lloyd, and philosopher John Dewey (1859-1952). Mead and Dewey became close personal and intellectual friends, finding much common ground in their interests in philosophy and psychology. In those days, the lines between philosophy and psychology were not sharply drawn, and Mead was to teach and do research in psychology throughout his career (mostly social psychology after 1910).

George and Helen Mead’s only child, Henry Castle Albert Mead, was born in Ann Arbor in 1892. When the boy grew up, he became a physician and married Irene Tufts (James Hayden Tufts’ daughter), a psychiatrist.

In 1892, having completed his Ph.D. work at Freiburg, James Hayden Tufts received an administrative appointment at the newly-created University of Chicago to help its founding president, William Rainey Harper, organize the new university (which opened in the fall of 1892). The University of Chicago was organized around three main departments: Semitics, chaired by J.M. Powis Smith; Classics, chaired by Paul Shorey; and Philosophy, chaired by John Dewey as of 1894. Dewey was recommended for that position by Tufts, and Dewey agreed to move from the University of Michigan to the University of Chicago provided that his friend and colleague, George Herbert Mead, was given a position as assistant professor in the Chicago philosophy department.

Thus, the University of Chicago became the new center of American Pragmatism (which had earlier originated with Charles Sanders Peirce [1839-1914] and William James at Harvard). The “Chicago Pragmatists” were led by Tufts, Dewey, and Mead. Dewey left Chicago for Columbia University in 1904, leaving Tufts and Mead as the major spokesmen for the Pragmatist movement in Chicago.

Mead spent the rest of his life in Chicago. He was assistant professor of philosophy from 1894-1902; associate professor from 1902-1907; and full professor from 1907 until his death in 1931. During those years, Mead made substantial contributions in both social psychology and philosophy. Mead’s major contribution to the field of social psychology was his attempt to show how the human self arises in the process of social interaction, especially by way of linguistic communication (“symbolic interaction”). In philosophy, as already mentioned, Mead was one of the major American Pragmatists. As such, he pursued and furthered the Pragmatist program and developed his own distinctive philosophical outlook centered around the concepts of sociality and temporality (see below).

Mrs. Helen Castle Mead died on December 25, 1929. George Mead was hit hard by her passing and gradually became ill himself. John Dewey arranged for Mead’s appointment as a professor in the philosophy department at Columbia University as of the 1931-1932 academic year, but before he could take up that appointment, Mead died in Chicago on April 26, 1931.

2. Writings

During his more-than-40-year career, Mead thought deeply, wrote almost constantly, and published numerous articles and book reviews in philosophy and psychology. However, he never published a book. After his death, several of his students edited four volumes from stenographic records of his social psychology course at the University of Chicago, from Mead’s lecture notes, and from Mead’s numerous unpublished papers. The four books are The Philosophy of the Present (1932), edited by Arthur E. Murphy; Mind, Self, and Society (1934), edited by Charles W. Morris; Movements of Thought in the Nineteenth Century (1936), edited by Merritt H. Moore; and The Philosophy of the Act (1938), Mead’s Carus Lectures of 1930, edited by Charles W. Morris.

Notable among Mead’s published papers are the following: “Suggestions Towards a Theory of the Philosophical Disciplines” (1900); “Social Consciousness and the Consciousness of Meaning” (1910); “What Social Objects Must Psychology Presuppose” (1910); “The Mechanism of Social Consciousness” (1912); “The Social Self” (1913); “Scientific Method and the Individual Thinker” (1917); “A Behavioristic Account of the Significant Symbol” (1922); “The Genesis of Self and Social Control” (1925); “The Objective Reality of Perspectives” (1926);”The Nature of the Past” (1929); and “The Philosophies of Royce, James, and Dewey in Their American Setting” (1929). Twenty-five of Mead’s most notable published articles have been collected in Selected Writings: George Herbert Mead, edited by Andrew J. Reck (Bobbs-Merrill, The Liberal Arts Press, 1964).

Most of Mead’s writings and much of the secondary literature thereon are listed in the References and Further Reading, below.

3. Social Theory

a. Communication and Mind

In Mind, Self and Society (1934), Mead describes how the individual mind and self arises out of the social process. Instead of approaching human experience in terms of individual psychology, Mead analyzes experience from the “standpoint of communication as essential to the social order.” Individual psychology, for Mead, is intelligible only in terms of social processes. The “development of the individual’s self, and of his self- consciousness within the field of his experience” is preeminently social. For Mead, the social process is prior to the structures and processes of individual experience.

Mind, according to Mead, arises within the social process of communication and cannot be understood apart from that process. The communicational process involves two phases: (1) the “conversation of gestures” and (2) language, or the “conversation of significant gestures.” Both phases presuppose a social context within which two or more individuals are in interaction with one another.

Mead introduces the idea of the “conversation of gestures” with his famous example of the dog-fight:

Dogs approaching each other in hostile attitude carry on such a language of gestures. They walk around each other, growling and snapping, and waiting for the opportunity to attack . . . . (Mind, Self and Society 14) The act of each dog becomes the stimulus to the other dog for his response. There is then a relationship between these two; and as the act is responded to by the other dog, it, in turn, undergoes change. The very fact that the dog is ready to attack another becomes a stimulus to the other dog to change his own position or his own attitude. He has no sooner done this than the change of attitude in the second dog in turn causes the first dog to change his attitude. We have here a conversation of gestures. They are not, however, gestures in the sense that they are significant. We do not assume that the dog says to himself, “If the animal comes from this direction he is going to spring at my throat and I will turn in such a way.” What does take place is an actual change in his own position due to the direction of the approach of the other dog. (Mind, Self and Society 42-43, emphasis added).

In the conversation of gestures, communication takes place without an awareness on the part of the individual of the response that her gesture elicits in others; and since the individual is unaware of the reactions of others to her gestures, she is unable to respond to her own gestures from the standpoint of others. The individual participant in the conversation of gestures is communicating, but she does not know that she is communicating. The conversation of gestures, that is, is unconscious communication.

It is, however, out of the conversation of gestures that language, or conscious communication, emerges. Mead’s theory of communication is evolutionary: communication develops from more or less primitive toward more or less advanced forms of social interaction. In the human world, language supersedes (but does not abolish) the conversation of gestures and marks the transition from non-significant to significant interaction.

Language, in Mead’s view, is communication through significant symbols. A significant symbol is a gesture (usually a vocal gesture) that calls out in the individual making the gesture the same (that is, functionally identical) response that is called out in others to whom the gesture is directed (Mind, Self and Society 47).

Significant communication may also be defined as the comprehension by the individual of the meaning of her gestures. Mead describes the communicational process as a social act since it necessarily requires at least two individuals in interaction with one another. It is within this act that meaning arises. The act of communication has a triadic structure consisting of the following components: (1) an initiating gesture on the part of an individual; (2) a response to that gesture by a second individual; and (3) the result of the action initiated by the first gesture (Mind, Self and Society 76, 81). There is no meaning independent of the interactive participation of two or more individuals in the act of communication.

Of course, the individual can anticipate the responses of others and can therefore consciously and intentionally make gestures that will bring out appropriate responses in others. This form of communication is quite different from that which takes place in the conversation of gestures, for in the latter there is no possibility of the conscious structuring and control of the communicational act.

Consciousness of meaning is that which permits the individual to respond to her own gestures as the other responds. A gesture, then, is an action that implies a reaction. The reaction is the meaning of the gesture and points toward the result (the “intentionality”) of the action initiated by the gesture. Gestures “become significant symbols when they implicitly arouse in an individual making them the same responses which they explicitly arouse, or are supposed [intended] to arouse, in other individuals, the individuals to whom they are addressed” (Mind, Self and Society 47). For example, “You ask somebody to bring a visitor a chair. You arouse the tendency to get the chair in the other, but if he is slow to act, you get the chair yourself. The response to the gesture is the doing of a certain thing, and you arouse that same tendency in yourself” (Mind, Self and Society 67). At this stage, the conversation of gestures is transformed into a conversation of significant symbols.

There is a certain ambiguity in Mead’s use of the terms “meaning” and “significance.” The question is, can a gesture be meaningful without being significant? But, if the meaning of a gesture is the response to that gesture, then there is meaning in the (non-significant) conversation of gestures — the second dog, after all, responds to the gestures of the first dog in the dog- fight and vice-versa.

However, it is the conversation of significant symbols that is the foundation of Mead’s theory of mind. “Only in terms of gestures as significant symbols is the existence of mind or intelligence possible; for only in terms of gestures which are significant symbols can thinking — which is simply an internalized or implicit conversation of the individual with himself by means of such gestures — take place” (Mind, Self and Society 47). Mind, then, is a form of participation in an interpersonal (that is, social) process; it is the result of taking the attitudes of others toward one’s own gestures (or conduct in general). Mind, in brief, is the use of significant symbols.

The essence of Mead’s so-called “social behaviorism” is his view that mind is an emergent out of the interaction of organic individuals in a social matrix. Mind is not a substance located in some transcendent realm, nor is it merely a series of events that takes place within the human physiological structure. Mead therefore rejects the traditional view of the mind as a substance separate from the body as well as the behavioristic attempt to account for mind solely in terms of physiology or neurology. Mead agrees with the behaviorists that we can explain mind behaviorally if we deny its existence as a substantial entity and view it instead as a natural function of human organisms. But it is neither possible nor desirable to deny the existence of mind altogether. The physiological organism is a necessary but not sufficient condition of mental behavior (Mind, Self and Society 139). Without the peculiar character of the human central nervous system, internalization by the individual of the process of significant communication would not be possible; but without the social process of conversational behavior, there would be no significant symbols for the individual to internalize.

The emergence of mind is contingent upon interaction between the human organism and its social environment; it is through participation in the social act of communication that the individual realizes her (physiological and neurological) potential for significantly symbolic behavior (that is, thought). Mind, in Mead’s terms, is the individualized focus of the communicational process — it is linguistic behavior on the part of the individual. There is, then, no “mind or thought without language;” and language (the content of mind) “is only a development and product of social interaction” (Mind, Self and Society 191- 192). Thus, mind is not reducible to the neurophysiology of the organic individual, but is an emergent in “the dynamic, ongoing social process” that constitutes human experience (Mind, Self and Society 7).

b. Action

For Mead, mind arises out of the social act of communication. Mead’s concept of the social act is relevant, not only to his theory of mind, but to all facets of his social philosophy. His theory of “mind, self, and society” is, in effect, a philosophy of the act from the standpoint of a social process involving the interaction of many individuals, just as his theory of knowledge and value is a philosophy of the act from the standpoint of the experiencing individual in interaction with an environment.

There are two models of the act in Mead’s general philosophy: (1) the model of the act-as-such, i.e., organic activity in general (which is elaborated in The Philosophy of the Act), and (2) the model of the social act, i.e., social activity, which is a special case of organic activity and which is of particular (although not exclusive) relevance in the interpretation of human experience. The relation between the “social process of behavior” and the “social environment” is “analogous” to the relation between the “individual organism” and the “physical-biological environment” (Mind, Self and Society 130).

The Act-As-Such

In his analysis of the act-as-such (that is, organic activity), Mead speaks of the act as determining “the relation between the individual and the environment” (The Philosophy of the Act 364). Reality, according to Mead, is a field of situations. “These situations are fundamentally characterized by the relation of an organic individual to his environment or world. The world, things, and the individual are what they are because of this relation [between the individual and his world]” (The Philosophy of the Act 215). It is by way of the act that the relation between the individual and his world is defined and developed.

Mead describes the act as developing in four stages: (1) the stage of impulse, upon which the organic individual responds to “problematic situations” in his experience (e.g., the intrusion of an enemy into the individual’s field of existence); (2) the stage of perception, upon which the individual defines and analyzes his problem (e.g., the direction of the enemy’s attack is sensed, and a path leading in the opposite direction is selected as an avenue of escape); (3) the stage of manipulation, upon which action is taken with reference to the individual’s perceptual appraisal of the problematic situation (e.g., the individual runs off along the path and away from his enemy); and (4) the stage of consummation, upon which the encountered difficulty is resolved and the continuity of organic existence re- established (e.g., the individual escapes his enemy and returns to his ordinary affairs) (The Philosophy of the Act 3-25). ]

What is of interest in this description is that the individual is not merely a passive recipient of external, environmental influences, but is capable of taking action with reference to such influences; he reconstructs his relation to his environment through selective perception and through the use or manipulation of the objects selected in perception (e.g., the path of escape mentioned above). The objects in the environment are, so to speak, created through the activity of the organic individual: the path along which the individual escapes was not “there” (in his thoughts or perceptions) until the individual needed a path of escape. Reality is not simply “out there,” independent of the organic individual, but is the outcome of the dynamic interrelation of organism and environment. Perception, according to Mead, is a relation between organism and object. Perception is not, then, something that occurs in the organism, but is an objective relation between the organism and its environment; and the perceptual object is not an entity out there, independent of the organism, but is one pole of the interactive perceptual process (The Philosophy of the Act 81).

Objects of perception arise within the individual’s attempt to solve problems that have emerged in his experience, problems that are, in an important sense, determined by the individual himself. The character of the individual’s environment is predetermined by the individual’s sensory capacities. The environment, then, is what it is in relation to a sensuous and selective organic individual; and things, or objects, “are what they are in the relationship between the individual and his environment, and this relationship is that of conduct [i.e., action]” (The Philosophy of the Act 218).

The Social Act

While the social act is analogous to the act-as-such, the above-described model of “individual biological activity” (Mind, Self and Society 130) will not suffice as an analysis of social experience. The “social organism” is not an organic individual, but “a social group of individual organisms” (Mind, Self and Society 130). The human individual, then, is a member of a social organism, and his acts must be viewed in the context of social acts that involve other individuals. Society is not a collection of preexisting atomic individuals (as suggested, for example, by Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau), but rather a processual whole within which individuals define themselves through participation in social acts. The acts of the individual are, according to Mead, aspects of acts that are trans- individual. “For social psychology, the whole (society) is prior to the part (the individual), not the part to the whole; and the part is explained in terms of the whole, not the whole in terms of the part or parts” (Mind, Self and Society 7). Thus, the social act is a “dynamic whole,” a “complex organic process,” within which the individual is situated, and it is within this situation that individual acts are possible and have meaning.

Mead defines the social act in relation to the social object. The social act is a collective act involving the participation of two or more individuals; and the social object is a collective object having a common meaning for each participant in the act. There are many kinds of social acts, some very simple, some very complex. These range from the (relatively) simple interaction of two individuals (e.g., in dancing, in love-making, or in a game of handball), to rather more complex acts involving more than two individuals (e.g., a play, a religious ritual, a hunting expedition), to still more complex acts carried on in the form of social organizations and institutions (e.g., law- enforcement, education, economic exchange). The life of a society consists in the aggregate of such social acts.

It is by way of the social act that persons in society create their reality. The objects of the social world (common objects such as clothes, furniture, tools, as well as scientific objects such as atoms and electrons) are what they are as a result of being defined and utilized within the matrix of specific social acts. Thus, an animal skin becomes a coat in the experience of people (e.g., barbarians or pretenders to aristocracy) engaged in the social act of covering and/or adorning their bodies; and the electron is introduced (as a hypothetical object) in the scientific community’s project of investigating the ultimate nature of physical reality.

Communication through significant symbols is that which renders the intelligent organization of social acts possible. Significant communication, as stated earlier, involves the comprehension of meaning, i.e., the taking of the attitude of others toward one’s own gestures. Significant communication among individuals creates a world of common (symbolic) meanings within which further and deliberate social acts are possible. The specifically human social act, in other words, is rooted in the act of significant communication and is, in fact, ordered by the conversation of significant symbols.

In addition to its role in the organization of the social act, significant communication is also fundamentally involved in the creation of social objects. For it is by way of significant symbols that humans indicate to one another the object relevant to their collective acts. For example, suppose that a group of people has decided on a trip to the zoo. One of the group offers to drive the others in his car; and the others respond by following the driver to his vehicle. The car has thus become an object for all members of the group, and they all make use of it to get to the zoo. Prior to this particular project of going to the zoo, the car did not have the specific significance that it takes on in becoming instrumental in the zoo-trip. The car was, no doubt, an object in some other social act prior to its incorporation into the zoo-trip; but prior to that incorporation, it was not specifically and explicitly a means of transportation to the zoo. Whatever it was, however, would be determined by its role in some social act (e.g., the owner’s project of getting to work each day, etc.). It is perhaps needless to point out that the decision to go to the zoo, as well as the decision to use the car in question as a means of transportation, was made through a conversation involving significant symbols. The significant symbol functions here to indicate “some object or other within the field of social behavior, an object of common interest to all the individuals involved in the given social act thus directed toward or upon that object” (Mind, Self and Society 46). The reality that humans experience is, for Mead, very largely socially constructed in a process mediated and facilitated by the use of significant symbols.

c. Self and Other

The Self as Social Emergent

The self, like the mind, is a social emergent. This social conception of the self, Mead argues, entails that individual selves are the products of social interaction and not the (logical or biological) preconditions of that interaction. Mead contrasts his social theory of the self with individualistic theories of the self (that is, theories that presuppose the priority of selves to social process). “The self is something which has a development; it is not initially there, at birth, but arises in the process of social experience and activity, that is, develops in the given individual as a result of his relations to that process as a whole and to other individuals within that process” (Mind, Self and Society 135). Mead’s model of society is an organic model in which individuals are related to the social process as bodily parts are related to bodies.

The self is a reflective process — i.e., “it is an object to itself.” For Mead, it is the reflexivity of the self that “distinguishes it from other objects and from the body.” For the body and other objects are not objects to themselves as the self is.

It is perfectly true that the eye can see the foot, but it does not see the body as a whole. We cannot see our backs; we can feel certain portions of them, if we are agile, but we cannot get an experience of our whole body. There are, of course, experiences which are somewhat vague and difficult of location, but the bodily experiences are for us organized about a self. The foot and hand belong to the self. We can see our feet, especially if we look at them from the wrong end of an opera glass, as strange things which we have difficulty in recognizing as our own. The parts of the body are quite distinguishable from the self. We can lose parts of the body without any serious invasion of the self. The mere ability to experience different parts of the body is not different from the experience of a table. The table presents a different feel from what the hand does when one hand feels another, but it is an experience of something with which we come definitely into contact. The body does not experience itself as a whole, in the sense in which the self in some way enters into the experience of the self (Mind, Self and Society 136).

It is, moreover, this reflexivity of the self that distinguishes human from animal consciousness (Mind, Self and Society, fn., 137). Mead points out two uses of the term “consciousness”: (1) “consciousness” may denote “a certain feeling consciousness” which is the outcome of an organism’s sensitivity to its environment (in this sense, animals, in so far as they act with reference to events in their environments, are conscious); and (2) “consciousness” may refer to a form of awareness “which always has, implicitly at least, the reference to an ‘I’ in it” (that is, the term “consciousness” may mean self– consciousness) (Mind, Self and Society 165). It is the second use of the term “consciousness” that is appropriate to the discussion of human consciousness. While there is a form of pre-reflective consciousness that refers to the “bare thereness of the world,” it is reflective (or self-) consciousness that characterizes human awareness. The pre-reflective world is a world in which the self is absent (Mind, Self and Society 135-136).

Self-consciousness, then, involves the objectification of the self. In the mode of self- consciousness, the “individual enters as such into his own experience . . . as an object” (Mind, Self and Society 225). How is this objectification of the self possible? The individual, according to Mead, “can enter as an object [to himself] only on the basis of social relations and interactions, only by means of his experiential transactions with other individuals in an organized social environment” (Mind, Self and Society 225). Self-consciousness is the result of a process in which the individual takes the attitudes of others toward herself, in which she attempts to view herself from the standpoint of others. The self-as-object arises out of the individual’s experience of other selves outside of herself. The objectified self is an emergent within the social structures and processes of human intersubjectivity.

Symbolic Interaction and the Emergence of the Self

Mead’s account of the social emergence of the self is developed further through an elucidation of three forms of inter-subjective activity: language, play, and the game. These forms of “symbolic interaction” (that is, social interactions that take place via shared symbols such as words, definitions, roles, gestures, rituals, etc.) are the major paradigms in Mead’s theory of socialization and are the basic social processes that render the reflexive objectification of the self possible.

Language, as we have seen, is communication via “significant symbols,” and it is through significant communication that the individual is able to take the attitudes of others toward herself. Language is not only a “necessary mechanism” of mind, but also the primary social foundation of the self:

I know of no other form of behavior than the linguistic in which the individual is an object to himself . . . (Mind, Self and Society 142). When a self does appear it always involves an experience of another; there could not be an experience of a self simply by itself. The plant or the lower animal reacts to its environment, but there is no experience of a self . . . . When the response of the other becomes an essential part in the experience or conduct of the individual; when taking the attitude of the other becomes an essential part in his behavior — then the individual appears in his own experience as a self; and until this happens he does not appear as a self (Mind, Self and Society 195).

Within the linguistic act, the individual takes the role of the other, i.e., responds to her own gestures in terms of the symbolized attitudes of others. This “process of taking the role of the other” within the process of symbolic interaction is the primal form of self-objectification and is essential to self- realization (Mind, Self and Society 160-161).

It ought to be clear, then, that the self-as-object of which Mead speaks is not an object in a mechanistic, billiard ball world of external relations, but rather it is a basic structure of human experience that arises in response to other persons in an organic social-symbolic world of internal (and inter- subjective) relations. This becomes even clearer in Mead’s interpretation of playing and gaming. In playing and gaming, as in linguistic activity, the key to the generation of self-consciousness is the process of role-playing.” In play, the child takes the role of another and acts as though she were the other (e.g., mother, doctor, nurse, Indian, and countless other symbolized roles). This form of role-playing involves a single role at a time. Thus, the other which comes into the child’s experience in play is a “specific other” (The Philosophy of the Present 169).

The game involves a more complex form of role-playing than that involved in play. In the game, the individual is required to internalize, not merely the character of a single and specific other, but the roles of all others who are involved with him in the game. He must, moreover, comprehend the rules of the game which condition the various roles (Mind, Self and Society 151). This configuration of roles-organized-according-to- rules brings the attitudes of all participants together to form a symbolized unity: this unity is the “generalized other” (Mind, Self and Society 154). The generalized other is “an organized and generalized attitude” (Mind, Self and Society 195) with reference to which the individual defines her own conduct. When the individual can view herself from the standpoint of the generalized other, “self- consciousness in the full sense of the term” is attained.

The game, then, is the stage of the social process at which the individual attains selfhood. One of Mead’s most outstanding contributions to the development of critical social theory is his analysis of games. Mead elucidates the full social and psychological significance of game-playing and the extent to which the game functions as an instrument of social control. The following passage contains a remarkable piece of analysis:

What goes on in the game goes on in the life of the child all the time. He is continually taking the attitudes of those about him, especially the roles of those who in some sense control him and on whom he depends. He gets the function of the process in an abstract way at first. It goes over from the play into the game in a real sense. He has to play the game. The morale of the game takes hold of the child more than the larger morale of the whole community. The child passes into the game and the game expresses a social situation in which he can completely enter; its morale may have a greater hold on him than that of the family to which he belongs or the community in which he lives. There are all sorts of social organizations, some of which are fairly lasting, some temporary, into which the child is entering, and he is playing a sort of social game in them. It is a period in which he likes “to belong,” and he gets into organizations which come into existence and pass out of existence. He becomes a something which can function in the organized whole, and thus tends to determine himself in his relationship with the group to which he belongs. That process is one which is a striking stage in the development of the child’s morale. It constitutes him a self-conscious member of the community to which he belongs (Mind, Self and Society 160, emphasis added).

The “Me” and the “I”

Although the self is a product of socio-symbolic interaction, it is not merely a passive reflection of the generalized other. The individual’s response to the social world is active; she decides what she will do in the light of the attitudes of others; but her conduct is not mechanically determined by such attitudinal structures. There are, it would appear, two phases (or poles) of the self: (1) that phase which reflects the attitude of the generalized other and (2) that phase which responds to the attitude of the generalized other. Here, Mead distinguishes between the “me” and the “I.” The “me” is the social self, and the “I” is a response to the “me” (Mind, Self and Society 178). “The ‘I’ is the response of the organism to the attitudes of the others; the ‘me’ is the organized set of attitudes of others which one himself assumes” (Mind, Self and Society 175). Mead defines the “me” as “a conventional, habitual individual,” and the “I” as the “novel reply” of the individual to the generalized other (Mind, Self and Society 197). There is a dialectical relationship between society and the individual; and this dialectic is enacted on the intra-psychic level in terms of the polarity of the “me” and the “I.” The “me” is the internalization of roles which derive from such symbolic processes as linguistic interaction, playing, and gaming; whereas the “I” is a “creative response” to the symbolized structures of the “me” (that is, to the generalized other).

Although the “I” is not an object of immediate experience, it is, in a sense, knowable (that is, objectifiable). The “I” is apprehended in memory; but in the memory image, the “I” is no longer a pure subject, but “a subject that is now an object of observation” (Selected Writings 142). We can understand the structural and functional significance of the “I,” but we cannot observe it directly — it appears only ex post facto. We remember the responses of the “I” to the “me;” and this is as close as we can get to a concrete knowledge of the “I.” The objectification of the “I” is possible only through an awareness of the past; but the objectified “I” is never the subject of present experience. “If you ask, then, where directly in your own experience the ‘I’ comes in, the answer is that it comes in as a historical figure” (Mind, Self and Society 174).

The “I” appears as a symbolized object in our consciousness of our past actions, but then it has become part of the “me.” The “me” is, in a sense, that phase of the self that represents the past (that is, the already-established generalized other). The “I,” which is a response to the “me,” represents action in a present (that is, “that which is actually going on, taking place”) and implies the restructuring of the “me” in a future. After the “I” has acted, “we can catch it in our memory and place it in terms of that which we have done,” but it is now (in the newly emerged present) an aspect of the restructured “me” (Mind, Self and Society 204, 203).

Because of the temporal-historical dimension of the self, the character of the “I” is determinable only after it has occurred; the “I” is not, therefore, subject to predetermination. Particular acts of the “I” become aspects of the “me” in the sense that they are objectified through memory; but the “I” as such is not contained in the “me.”

The human individual exists in a social situation and responds to that situation. The situation has a particular character, but this character does not completely determine the response of the individual; there seem to be alternative courses of action. The individual must select a course of action (and even a decision to do “nothing” is a response to the situation) and act accordingly, but the course of action she selects is not dictated by the situation. It is this indeterminacy of response that “gives the sense of freedom, of initiative” (Mind, Self and Society 177). The action of the “I” is revealed only in the action itself; specific prediction of the action of the “I” is not possible. The individual is determined to respond, but the specific character of her response is not fully determined. The individual’s responses are conditioned, but not determined by the situation in which she acts (Mind, Self and Society 210-211). Human freedom is conditioned freedom.

Thus, the “I” and the “me” exist in dynamic relation to one another. The human personality (or self) arises in a social situation. This situation structures the “me” by means of inter-subjective symbolic processes (language, gestures, play, games, etc.), and the active organism, as it continues to develop, must respond to its situation and to its “me.” This response of the active organism is the “I.”

The individual takes the attitude of the “me” or the attitude of the “I” according to situations in which she finds herself. For Mead, “both aspects of the ‘I’ and the ‘me’ are essential to the self in its full expression” (Mind, Self and Society 199). Both community and individual autonomy are necessary to identity. The “I” is process breaking through structure. The “me” is a necessary symbolic structure which renders the action of the “I” possible, and “without this structure of things, the life of the self would become impossible” (Mind, Self and Society 214).

The Dialectic of Self and Other

The self arises when the individual takes the attitude of the generalized other toward herself. This “internalization” of the generalized other occurs through the individual’s participation in the conversation of significant symbols (that is, language) and in other socialization processes (e.g., play and games). The self, then, is of great value to organized society: the internalization of the conversation of significant symbols and of other interactional symbolic structures allows for “the superior co-ordination” of “society as a whole,” and for the “increased efficiency of the individual as a member of the group” (Mind, Self and Society 179). The generalized other (internalized in the “me”) is a major instrument of social control; it is the mechanism by which the community gains control “over the conduct of its individual members” (Mind, Self and Society 155).”Social control,” in Mead’s words, “is the expression of the ‘me’ over against the expression of the ‘I'” (Mind, Self and Society 210).

The genesis of the self in social process is thus a condition of social control. The self is a social emergent that supports the cohesion of the group; individual will is harmonized, by means of a socially defined and symbolized “reality,” with social goals and values. “In so far as there are social acts,” writes Mead, “there are social objects, and I take it that social control is bringing the act of the individual into relation with this social object” (The Philosophy of the Act 191). Thus, there are two dimensions of Mead’s theory of internalization: (1) the internalization of the attitudes of others toward oneself and toward one another (that is, internalization of the interpersonal process); and (2) the internalization of the attitudes of others “toward the various phases or aspects of the common social activity or set of social undertakings in which, as members of an organized society or social group, they are all engaged” (Mind, Self and Society 154-155).

The self, then, has reference, not only to others, but to social projects and goals, and it is by means of the socialization process (that is, the internalization of the generalized other through language, play, and the game) that the individual is brought to “assume the attitudes of those in the group who are involved with him in his social activities” (The Philosophy of the Act 192). By learning to speak, gesture, and play in “appropriate” ways, the individual is brought into line with the accepted symbolized roles and rules of the social process. The self is therefore one of the most subtle and effective instruments of social control.

For Mead, however, social control has its limits. One of these limits is the phenomenon of the “I,” as described in the preceding section. Another limit to social control is presented in Mead’s description of specific social relations. This description has important consequences regarding the way in which the concept of the generalized other is to be applied in social analysis.

The self emerges out of “a special set of social relations with all the other individuals” involved in a given set of social projects (Mind, Self and Society 156-157). The self is always a reflection of specific social relations that are themselves founded on the specific mode of activity of the group in question. The concept of property, for example, presupposes a community with certain kinds of responses; the idea of property has specific social and historical foundations and symbolizes the interests and values of specific social groups.

Mead delineates two types of social groups in civilized communities. There are, on the one hand, “concrete social classes or subgroups” in which “individual members are directly related to one another.” On the other hand, there are “abstract social classes or subgroups” in which “individual members are related to one another only more or less indirectly, and which only more or less indirectly function as social units, but which afford unlimited possibilities for the widening and ramifying and enriching of the social relations among all the individual members of the given society as an organized and unified whole” (Mind, Self and Society 157). Such abstract social groups provide the opportunity for a radical extension of the “definite social relations” which constitute the individual’s sense of self and which structure her conduct.

Human society, then, contains a multiplicity of generalized others. The individual is capable of holding membership in different groups, both simultaneously and serially, and may therefore relate herself to different generalized others at different times; or she may extend her conception of the generalized other by identifying herself with a “larger” community than the one in which she has hitherto been involved (e.g., she may come to view herself as a member of a nation rather than as a member of a tribe). The self is not confined within the limits of any one generalized other. It is true that the self arises through the internalization of the generalized attitudes of others, but there is, it would appear, no absolute limit to the individual’s capacity to encompass new others within the dynamic structure of the self. This makes strict and total social control difficult if not impossible.

Mead’s description of social relations also has interesting implications vis-a-vis the sociological problem of the relation between consensus and conflict in society. It is clear that both consensus and conflict are significant dimensions of social process; and in Mead’s view, the problem is not to decide either for a consensus model of society or for a conflict model, but to describe as directly as possible the function of both consensus and conflict in human social life.

There are two models of consensus-conflict relation in Mead’s analysis of social relations. These may be schematized as follows:

- Intra-Group Consensus — Extra-Group Conflict

- Intra-Group Conflict — Extra-Group Consensus

In the first model, the members of a given group are united in opposition to another group which is characterized as the “common enemy” of all members of the first group. Mead points out that the idea of a common enemy is central in much of human social organization and that it is frequently the major reference-point of intra-group consensus. For example, a great many human organizations derive their raison d’etre and their sense of solidarity from the existence (or putative existence) of the “enemy” (communists, atheists, infidels, fascist pigs, religious “fanatics,” liberals, conservatives, or whatever). The generalized other of such an organization is formed in opposition to the generalized other of the enemy. The individual is “with” the members of her group and “against” members of the enemy group.

Mead’s second model, that of intra-group conflict and extra-group consensus, is employed in his description of the process in which the individual reacts against her own group. The individual opposes her group by appealing to a “higher sort of community” that she holds to be superior to her own. She may do this by appealing to the past (e.g., she may ground her criticism of the bureaucratic state in a conception of “Jeffersonian Democracy”), or by appealing to the future (e.g., she may point to the ideal of “all mankind,” of the universal community, an ideal that has the future as its ever-receding reference point). Thus, intra-group conflict is carried on in terms of an extra-group consensus, even if the consensus is merely assumed or posited. This model presupposes Mead’s conception of the multiplicity of generalized others, i.e., the field within which conflicts are possible. It is also true that the individual can criticize her group only in so far as she can symbolize to herself the generalized other of that group; otherwise she would have nothing to criticize, nor would she have the motivation to do so. It is in this sense that social criticism presupposes social- symbolic process and a social self capable of symbolic reflexive activity.

In addition to the above-described models of consensus-conflict relation, Mead also points out an explicitly temporal interaction between consensus and conflict. Human conflicts often lead to resolutions that create new forms of consensus. Thus, when such conflicts occur, they can lead to whole “reconstructions of the particular social situations” that are the contexts of the conflicts (e.g., a war between two nations may be followed by new political alignments in which the two warring nations become allies). Such reconstructions of society are effected by the minds of individuals in conflict and constitute enlargements of the social whole.

An interesting consequence of Mead’s analysis of social conflict is that the reconstruction of society will entail the reconstruction of the self. This aspect of the social dynamic is particularly clear in terms of Mead’s concept of intra-group conflict and his description of the dialectic of the “me” and the “I.” As pointed out earlier, the “I” is an emergent response to the generalized other; and the “me” is that phase of the self that represents the social situation within which the individual must operate. Thus, the critical capacity of the self takes form in the “I” and has two dimensions: (1) explicit self- criticism (aimed at the “me”) is implicit social criticism; and (2) explicit social criticism is implicit self- criticism. For example, the criticism of one’s own moral principles is also the criticism of the morality of one’s social world, for personal morality is rooted in social morality. Conversely, the criticism of the morality of one’s society raises questions concerning one’s own moral role in the social situation.

Since self and society are dialectical poles of a single process, change in one pole will result in change in the other pole. It would appear that social reconstructions are effected by individuals (or groups of individuals) who find themselves in conflict with a given society; and once the reconstruction is accomplished, the new social situation generates far-reaching changes in the personality structures of the individuals involved in that situation.” In short,” writes Mead, “social reconstruction and self or personality reconstruction are the two sides of a single process — the process of human social evolution” (Mind, Self and Society 309).

4. The Temporal Structure of Human Existence

The temporal structure of human existence, according to Mead, can be described in terms of the concepts of emergence, sociality, and freedom.

Emergence and Temporality

What is the ground of the temporality of human experience? Temporal structure, according to Mead, arises with the appearance of novel or “emergent” events in experience. The emergent event is an unexpected disruption of continuity, an inhibition of passage. The emergent, in other words, constitutes a problem for human action, a problem to be overcome. The emergent event, which arises in a present, establishes a barrier between present and future; emergence is an inhibition of (individual and collective) conduct, a disharmony that projects experience into a distant future in which harmony may be re-instituted. The initial temporal structure of human time-consciousness lies in the separation of present and future by the emergent event. The actor, blocked in his activity, confronts the emergent problem in his present and looks to the future as the field of potential resolution of conflict. The future is a temporally, and frequently spatially, distant realm to be reached through intelligent action. Human action is action-in-time.

Mead argues out that, without inhibition of activity and without the distance created by the inhibition, there can be no experience of time. Further, Mead believes that, without the rupture of continuity, there can be no experience at all. Experience presupposes change as well as permanence. Without disruption, “there would be merely the passage of events” (The Philosophy of the Act 346), and mere passage does not constitute change. Passage is pure continuity without interruption (a phenomenon of which humans, with the possible exception of a few mystics, have precious little experience). Change arises with a departure from continuity. Change does not, however, involve the total obliteration of continuity — there must be a “persisting non-passing content” against which an emergent event is experienced as a change (The Philosophy of the Act 330-331).

Experience begins with the problematic. Continuity itself cannot be experienced unless it is broken; that is, continuity is not an object of awareness unless it becomes problematic, and continuity becomes problematic as a result of the emergence of discontinuous events. Hence, continuity and discontinuity (emergence) are not contradictories, but dialectical polarities (mutually dependent levels of reality) that generate experience itself. “The now is contrasted with a then and implies that a background which is irrelevant to the difference between them has been secured within which the now and the then may appear. There must be banks within which the stream of time may flow” (The Philosophy of the Act 161).

Emergence, then, is a fundamental condition of experience, and the experience of the emergent is the experience of temporality. Emergence sunders present and future and is thereby an occasion for action. Action, moreover, occurs in time; the human act is infected with time — it aims at the future. Human action is teleological. Discontinuity, therefore, and not continuity (in the sense of mere duration or passage), is the foundation of time-experience (and of experience itself). The emergent event constitutes time, i.e., creates the necessity of time.

The Function of the Past in Human Experience

The emergent event is not only a problem for ongoing activity: it also constitutes a problem for rationality. Reason, according to Mead, is the search for causal continuity in experience and, in fact, must presuppose such continuity in its attempt to construct a coherent account of reality. Reason must assume that all natural events can be reduced to conditions that make the events possible. But the emergent event presents itself as discontinuous, as a disruption without conditions.

It is by means of the reconstruction of the past that the discontinuous event becomes continuous in experience: “The character of the past is that it connects what is unconnected in the merging of one present into another” (“The Nature of the Past” [1929], in Selected Writings 351). The emergent event, when placed within a reconstructed past, is a determined event; but since this past was reconstructed from the perspective of the emergent event, the emergent event is also a determining event (The Philosophy of the Present 15). The emergent event itself indicates the continuities within which the event may be viewed as continuous. There is, then, no question of predicting the emergent, for it is, by definition and also experientially, unpredictable; but once the emergent appears in experience, it may be placed within a continuity dictated by its own character. Determination of the emergent is retrospective determination.

Mead’s conception of time entails a drastic revision of the idea of the irrevocability of the past. The past is “both irrevocable and revocable” (The Philosophy of the Present 2). There is no sense in the idea of an independent or “real” past, for the past is always formulated in the light of the emerging present. It is necessary to continually reformulate the past from the point of view of the newly emergent situation. For example, the movement for the liberation of African-Americans has led to the discovery of the American black’s cultural past. “Black (or African-American) History” is, in effect, a function of the emergence of the civil rights movement in the late 1940s and early 1950s and the subsequent development of that movement. As far as most Americans were hitherto concerned, there simply was no history of the American black — there was only a history of white Europeans, which included the history of slavery in America.

There can be no finality in historical accounts. The past is irrevocable in the sense that something has happened; but what has happened (that is, the essence of the past) is always open to question and reinterpretation. Further, the irrevocability of the past “is found in the extension of the necessity with which what has just happened conditions what is emerging in the future” (The Philosophy of the Present 3). Irrevocability is a characteristic of the past only in relation to the demands of a present looking into the future. That is to say that even the sense that something has happened arises out of a situation in which an emergent event has appeared as a problem.

Like Edmund Husserl, Mead conceives of human consciousness as intentional in its structure and orientation: the world of conscious experience is “intended,” “meant,” “constituted,” “constructed” by consciousness. Thus, objectivity can have meaning only within the domain of the subject, the realm of consciousness. It is not that the existence of the objective world is constituted by consciousness, but that the meaning of that world is so constituted. In Husserlian language, the existence of the objective world is transcendent, i.e., independent of consciousness; but the meaning of the objective world is immanent, i.e., dependent on consciousness. In Mead’s “phenomenology” of historical experience, then, the past may be said to possess an objective existence, but the meaning of the past is constituted or constructed according to the intentional concerns of historical thought. The meaning of the past (“what has happened”) is defined by an historical consciousness that is rooted in a present and that is opening upon a newly emergent future.

History is founded on human action in response to emergent events. Action is an attempt to adjust to changes that emerge in experience; the telos of the act is the re-establishment of a sundered continuity. Since the past is instrumental in the re-establishment of continuity, the adjustment to the emergent requires the creation of history. “By looking into the future,” Mead observes, “society acquired a history” (The Philosophy of the Act 494). And the future- orientation of history entails that every new discovery, every new project, will alter our picture of the past.

Although Mead discounts the possibility of a transcendent past (that is, a past independent of any present), he does not deny the possibility of validity in historical accounts. An historical account will be valid or correct, not absolutely, but in relation to a specific emergent context. Accounts of the past “become valid in interpreting [the world] in so far as they present a history of becoming in [the world] leading up to that which is becoming today . . . . ” (The Philosophy of the Present 9). Historical thought is valid in so far as it renders change intelligible and permits the continuation of activity. An appeal to an absolutely correct account of the past is not only impossible, but also irrelevant to the actual conduct of historical inquiry. A meaningful past is a usable past.

Historians are, to be sure, concerned with the truth of historical accounts, i.e., with the “objectivity” of the past. The historical conscience seeks to reconstruct the past on the basis of evidence and to present an accurate interpretation of the data of history. Mead’s point is that all such reconstructions and interpretations of the past are grounded in a present that is opening into a future and that the time-conditioned nature and interests of historical thought made the construction of a purely “objective” historical account impossible. Historical consciousness is “subjective” in the sense that it aims at an interpretation of the past that will be humanly meaningful in the present and in the foreseeable future. Thus, for Mead, historical inquiry is the imaginative-but-honest, intelligent-and-intelligible reconstruction and interpretation of the human past on the basis of all available and relevant evidence. Above all, the historian seeks to define the meaning of the human past and, in that way, to make a contribution to humanity’s search for an overall understanding of human existence.

Sociality and Time

The emergent event, then, is basic to Mead’s theory of time. The emergent event is a becoming, an unexpected occurrence “which in its relation to other events gives structure to time” (The Philosophy of the Present 21). But what is the ontological status of emergence? What is its relation to the general structure of reality? The possibility of emergence is grounded in Mead’s conception of the relatedness, the “sociality,” of natural processes.

Mead’s philosophy arises from a fundamental ecological vision of the world, a vision of the world containing a multiplicity of related systems (e.g., the bee system and the flower system, which together form the bee-flower system). Nature is a system of systems or relationships; it is not a collection of particles or fragments which are actually separate. Distinctions, for Mead, are abstractions within fields of activity; and all natural objects (animate or inanimate) exist within systems apart from which the existence of the objects themselves is unthinkable.

The sense of the organic body arises with reference to “external” objects; and these external objects in turn derive their character from their relation to an organic individual. The body-object and the physical object arise with reference to each other, and it is this relationship, in Mead’s view, that constitutes the reality of each referent. “It is over against the surfaces of other things that the outside of the organism arises in experience, and then the experiences of the organism which are not in such contacts become the inside of the organism. It is a process in which the organism is bounded, and other things are bounded as well” (The Philosophy of the Act 160). Similarly, the resistance of the object to organic pressure is, in effect, the activity of the object; and this activity becomes the “inside” of the object. The inside of the object, moreover, is not a projection from the organism, but is there in the relation between the organism and thing (see The Philosophy of the Present 122-124, 131, 136). The relation between organism and object, then, is a social relation (The Philosophy of the Act 109-110).

Thus, the relation between a natural object (or event) and the system within which it exists is not unidirectional. The character of the object, on the one hand, is determined by its membership in a system; but, on the other hand, the character of the system is determined by the activity of the object (or event). There is a mutual determination of object and system, organism and environment, percipient event and consentient set (The Philosophy of the Act 330).

While this mutuality of individual and system is characteristic of all natural processes, Mead is particularly concerned with the biological realm and lays great emphasis on the interdependence and interaction of organism and environment. Whereas the environment provides the conditions within which the acts of the organism emerge as possibilities, it is the activity of the organism that transforms the character of the environment. Thus, “an animal with the power of digesting and assimilating what could not before be digested and assimilated is the condition for the appearance of food in his environment” (The Philosophy of the Act 334). In this respect, “what the individual is determines what the character of his environment will be” (The Philosophy of the Act 338).

The relation of organism and environment is not static, but dynamic. The activities of the environment alter the organism, and the activities of the organism alter the environment. The organism-environment relation is, moreover, complex rather than simple. The environment of any organism contains a multiplicity of processes, perspectives, systems, any one of which may become a factor in the organism’s field of activity. The ability of the organism to act with reference to a multiplicity of situations is an example of the sociality of natural events. And it is by virtue of this sociality, this “capacity of being several things at once” (The Philosophy of the Present 49), that the organism is able to encounter novel occurrences.

By moving from one system to another, the organism confronts unfamiliar and unexpected situations which, because of their novelty, constitute problems of adjustment for the organism. These emergent situations are possible given the multiplicity of natural processes and given the ability of natural events (e.g., organisms) to occupy several systems at once. A bee, for example, is capable of relating to other bees, to flowers, to bears, to little boys, albeit with various attitudes. But sociality is not restricted to animate events. A mountain may be simultaneously an aspect of geography, part of a landscape, an object of religious veneration, the dialectical pole of a valley, and so forth. The capacity of sociality is a universal character of nature.

There are, then, two modes of sociality: (1) Sociality characterizes the “process of readjustment” by which an organism incorporates an emergent event into its ongoing experience. This sociality in passage, which is “given in immediate relation of the past and present,” constitutes the temporal mode of sociality (The Philosophy of the Present 51). (2) A natural event is social, not only by virtue of its dynamic relationship with newly emergent situations, but also by virtue of its simultaneous membership in different systems at any given instant. In any given present, “the location of the object in one system places it in the others as well” (The Philosophy of the Present 63). The object is social, not merely in terms of its temporal relations, but also in terms of its relations with other objects in an instantaneous field. This mode of sociality constitutes the emergent event; that is, the state of a system at a given instant is the social reality within which emergent events occur, and it is this reality that must be adjusted to the exigencies of time. Thus, the principle of sociality is the ontological foundation of Mead’s concept of emergence: sociality is the ground of the possibility of emergence as well as the basis on which emergent events are incorporated into the structure of ongoing experience.

Temporality and the Problem of Freedom

When Mead’s theory of the self is placed in the context of his description of the temporality of human existence, it is possible to construct an account, not only of the reality of human freedom, but also of the conditions that give rise to the experience of loss of freedom.

Mead grounds his analysis of human consciousness in the social process of communication and, on that foundation, makes “the other” an integral part of self- understanding. The world in which the self lives, then, is an inter- subjective and interactive world — a “populated world” containing, not only the individual self, but also other persons. Intersubjectivity is to be explained in terms of that “meeting of minds” which occurs in conversation, learning, reading, and thinking (The Philosophy of the Act 52-53). It is on the basis of such socio-symbolic interactions between individuals, and by means of the conceptual symbols of the communicational process, that the mind and the self come into existence.

The human world is also temporally structured, and the temporality of experience, Mead argues, is a flow that is primarily present. The past is part of my experience now, and the projected future is also part of my experience now. There is hardly a moment when, turning to the temporality of my life, I do not find myself existing in the now. Thus, it would appear that whatever is for me, is now; and, needless to say, whatever is of importance or whatever is meaningful for me, is of importance or is meaningful now. This is true even if that which is important and meaningful for me is located in the “past” or in the “future.” Existential time is time lived in the now. My existence is rooted in a “living present,” and it is within this “living present” that my life unfolds and discloses itself. Thus, to gain full contact with oneself, it is necessary to focus one’s consciousness on the present and to appropriate that present (that “existential situation”) as one’s own.

This “philosophy of the present” need not lead to a careless, “live only for today” attitude. Our past is always with us (in the form of memory, history, tradition, etc.), and it provides a context for the “living present.” We live “in the present,” but also “out of the past;” and to live well now, we cannot afford to “forget” the past. A fully meaningful human existence must be “lived now,” but with continual reference to the past: we must continue to affirm “that which has been good,” and we must work to eliminate or to avoid “that which has been bad.” Moreover, a full human existence must be lived, not only in-the-present-out-of-the-past, but also in- the-present-toward-the-future. The human present opens toward the future. “Today” must always be lived with a concern for “tomorrow,” for we are continually moving toward the future, whether we like it or not. Further, we are “called” into this future, toward ever new possibilities; and we must, if we wish to live well, develop a “right mindfulness” which orients our present- centered consciousness toward the possibilities and challenges of the impending future. But we must “live now” with reference to both past and future.

The self, as we have seen, is characterized in part by its activity (the “I”) in response to its world, and how the individual is active with respect to his world is through his choices and his awareness of his choices. The individual experiences himself as having choices, or as being confronted with situations which require choices on his part. He does not (ordinarily) experience himself as being controlled by the world. The world presents obstacles to him, and yet he experiences himself as being able to respond to these obstacles in a variety (even though a finite variety) of ways.

One loses one’s freedom, even one’s selfhood, when one is unaware of one’s choices or when one refuses to face the fact that one has choices. From the standpoint of Mead’s description of the temporality of action and his emphasis on the importance of problematic situations in human experience, emergencies or “crises” in one’s life are of the utmost existential significance. I am a being that exists in relation to a world. As such, it is essential that I experience myself as “in harmony with” the world; and if this proves difficult or impossible, then I am thrown into a “crisis,” i.e., I am threatened with separation (Greek, krisis) from the world; and separation from the world, from the standpoint of a being- in-the-world, is tantamount to non- being. It is in this context that the loss of one’s freedom, the experience of lost autonomy, becomes a real possibility. Encountering a crisis in the process of life, the individual may well experience himself as paralyzed, as “stuck” in his situation, as patient rather than as agent of change. But it is also the case that the experience of crisis may lead to a deepened sense of one’s active involvement in the temporal unfolding of life. From Mead’s point of view, a crisis is a “crucial time” or a turning-point in individual existence: negatively, it is a threat to the individual’s continuity in and with his world; positively, it is an opportunity to redefine, broaden, and deepen the individual’s sense of self and of the world to which the self is ontologically related.

Thus, it would appear that crises may in fact undermine the sense of freedom of choice; and yet, it is also true that crises constitute opportunities for the exercise of freedom since such “breaks” or discontinuities in our experience demand that we make decisions as to what we are “going to do now.” In this way, break-downs might be viewed as break-throughs. Freedom denied on one level of experience is rediscovered at another. One must lose oneself in order to find oneself.

5. Perception and Reflection: Mead’s Theory of Perspectives

Mead’s concept of sociality, as we have seen, implies a vision of reality as situational, or perspectival. A perspective is “the world in its relationship to the individual and the individual in his relationship to the world” (The Philosophy of the Act 115). A perspective, then, is a situation in which a percipient event (or individual) exists with reference to a consentient set (or environment) and in which a consentient set exists with reference to a percipient event. There are, obviously, many such situations (or perspectives). These are not, in Mead’s view, imperfect representations of “an absolute reality” that transcends all particular situations. On the contrary, “these situations are the reality” which is the world (The Philosophy of the Act 215).

Distance Experience

For Mead, perceptual objects arise within the act and are instrumental in the consummation of the act. At the perceptual stage of the act, these objects are distant from the perceiving individual: they are “over there;” they are “not here” and “not now.” The distance is both spatial and temporal. Such objects invite the perceiving individual to act with reference to them, to “make contact” with them. Thus, Mead speaks of perceptual objects as “plans of action” that “control” the “action of the individual” (The Philosophy of the Present 176 and The Philosophy of the Act 262). Distance experience implies contact experience. Perception leads on to manipulation.