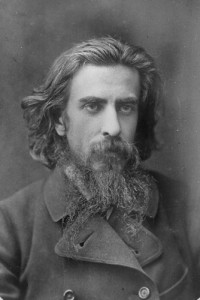

Vladimir Solovyov (1853—1900)

Solovyov was a 19th Century Russian Philosopher. He is considered a prolific but complicated character. His output aimed to be a comprehensive philosophical system, yet he produced what is considered contentious, theosophical and fundamentally inconclusive results.

Solovyov was a 19th Century Russian Philosopher. He is considered a prolific but complicated character. His output aimed to be a comprehensive philosophical system, yet he produced what is considered contentious, theosophical and fundamentally inconclusive results.

This article examines in detail Slovyov’s five main works. It also looks into the controversy he generated and his possible philosophical legacy. In the course of five main works – three were completed, two were left unfinished – Solovyov demonstrated a predilection for grand topics of study and an ambitious aim to produce a comprehensive philosophical system that rejected accepted notions of contemporary European Philosophy. In his first major work, The Crisis of Western Philosophy (written when he was twenty-one), he argues against positivism and for moving away from a dichotomy of “speculative” (rationalist) and “empirical” knowledge in favour of a post-philosophical enquiry that would reconcile all notions of thought in a new transcendental whole.

He carried on his attempted synthesis of rationalism, empiricism and mysticism in Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge, and he turned to a study of ethics leading to a solidifying of his epistemology in Critique of Abstract Principles.

In the later period of his life, he recast his ethics in The Justification of the Good and his epistemology in Theoretical Philosophy.

Due to his conclusions repeatedly resting on a call upon an aspect of the divine or the discovery of an “all-encompassing spirit,” the soundness of his arguments have often been called into question. For the same reason, and compounded by a tendency to express himself in theological and romantically nationalist language, he is also often dismissed as a mystic or fanatic. Although, as the article below argues, if read as a product of his time, they are more sensible and less polemical.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Interpretations of Solovyov’s Philosophical Writings.

- The Crisis of Western Philosophy

- Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge

- Critique of Abstract Principles

- The Justification of the Good

- Theoretical Philosophy

- Concluding Remarks

- References and Further Reading

1. Life

Solovyov was born in Moscow in 1853. His father, Sergej Mikhailovich, a professor at Moscow University, is universally recognized as one of Russia’s greatest historians. After attending secondary school in Moscow, Vladimir enrolled at the university and began his studies there in the natural sciences in 1869, his particular interest at this time being biology. Already at the age of 13 he had renounced his Orthodox faith to his friends, accepting the banner of materialism perhaps best illustrated by the fictional character of Bazarov in Turgenev’s novel Fathers and Sons and the actual historical figure of Pisarev. During the first two or three years of study at the university Solovyov grew disenchanted with his ardent positivism and did poorly in his examinations. An excellent student prior to this time, there is no reason for us to doubt his intellectual gifts. Nevertheless, although he himself as well as his interpreters have attributed his poor performance to growing disinterest in his course of study, this reasoning may sound to us at least somewhat disingenuous. In any case, Solovyov subsequently enrolled as an auditor in the Historical-Philosophical Faculty, then passing the examination for a degree in June 1873.

At some point during 1872 Solovyov reconverted, so to speak, to Orthodoxy. During the academic year 1873-74 he attended lectures at the Moscow Ecclesiastic Academy–an unusual step for a lay person. At this time Solovyov also began the writing of his magister’s dissertation, several chapters of which were published in a Russian theological journal in advance of’ his formal defense of it in early December 1874.

The death of his Moscow University philosophy teacher Pamfil Jurkevich created a vacancy that Solovyov surely harbored hopes of eventually filling. Nevertheless, despite being passed over, owing, at least in part, to his young age and lack of credentials, he was named a docent (lecturer) in philosophy. In spite of taking up his teaching duties with enthusiasm, within a few months Solovyov applied for a scholarship to do research abroad, primarily in London’s British Museum.

His stay in the English capital was met with mixed emotions, but it could not have been entirely unpleasant, for in mid-September 1875 he was still informing his mother of plans to return to Russia only the following summer. For whatever reason, though, Solovyov abruptly changed his mind, writing again to his mother a mere month later that his work required him to go to Egypt via Italy and Greece. Some have attributed his change of plans to a mystical experience while sitting in the reading room of the Museum!

Upon his return to Russia the following year, Solovyov taught philosophy at Moscow University. He began work on a text that we know as the Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge, but which he never finished. In early 1877 Solovyov relinquished his university position due to his aversion towards academic politics, took up residence in St. Petersburg and accepted employment in the Ministry of Public Education. While preparing his doctoral dissertation, Solovyov gave a series of highly successful popular lectures at St. Petersburg University that was later published as Lectures on Divine Humanity, and in 1880 he defended a doctoral dissertation at St. Petersburg University. Any lingering hope Solovyov may have entertained of obtaining a professorship in Russia were dashed when in early 1881 during a public lecture he appealed to the Tsar to pardon the regicides of the latter’s father Alexander II.

For the remainder of the 1880s, despite his prolificacy, Solovyov concerned himself with themes of little interest to contemporary Western philosophy. He returned, however, to traditional philosophical issues in the 1890s, working in particular on ethics and epistemology. His studies on the latter, however, were left quite incomplete owing to his premature death in 1900 at the age of 47. At the end Solovyov, together with his younger brother, was also preparing a new Russian translation of Plato’s works.

2. Interpretations of Solovyov’s Philosophical Writings

Despite the vast amount of secondary literature, particularly, of course, in Russian, little, especially that in English, is of interest to the professionally-trained philosopher. Nevertheless, even while memory of him was still fresh, many of his friends differed sharply on key issues involved in interpreting Solovyov’s writings and legacy.

Among the topics debated over the years has been the number of phases or periods through which his thought passed. Opinions have ranged from four to just one, depending largely on the different criteria selected for demarcating one period from another. Those who hold that Solovyov’s thought underwent no “fundamental change” [Shein] do not deny that there were modifications but simply maintain that the fundamental thrust of his philosophy remained unaltered over the course of time. Others see different emphases in Solovyov’s work from decade to decade. Yet in one of the most philosophically-informed interpretations, Solovyov moved from a philosophy of “integral knowledge” to a later phenomenological phase that anticipated the “essential methodology” of the German movement [Dahm].

Historically, another central concern among interpreters has been the extent of Solovyov’s indebtedness to various other figures. Whereas several have stressed the influence of, if not an outright borrowing from, the late Schelling [Mueller, Shein], at least one prominent scholar has sought to accentuate Solovyov’s independence and creativity [Losev]. Still others have argued for Solovyov’s indebtedness to Hegel [Navickas], Kant [Vvedenskij], Boehme [David], the Russian Slavophiles and the philosophically-minded theologians Jurkevich and Kudryavtsev.

In Russia itself the thesis that Solovyov had no epistemology [Radlov] evoked a spirited rebuttal [Ern] that has continued in North America [Shein, Navickas]. None of these scholars, however, has demonstrated the presence of more than a rudimentary epistemology, at least as that term is currently employed in contemporary philosophy.

Additionally, the vast majority of secondary studies have dealt with Solovyov’s mysticism and views on religion, nationalism, social issues, and the role of Russia in world history. Consequently, it is not surprising that those not directly acquainted with his explicit philosophical writings and their Russian context view Solovyov as having nothing of interest to say in philosophy proper. We should also mention one of the historically most influential views, one that initially at least appears quite plausible. Berdyaev, seeing Solovyov as a paradoxical figure, distinguished a day — from a night-Solovyov. The “day-Solovyov” was a philosophical rationalist, in the broad sense, an idealist, who sought to convey his highly metaphysical religious and ontological conceptions through philosophical discourse utilizing terms current at the time; the “night — Solovyov” was a mystic who conveyed his personal revelations largely through poetry.

3. The Crisis of Western Philosophy

This, Solovyov’s first major work, displays youthful enthusiasm, vision, optimism and a large measure of audacity. Unfortunately, it is also at times repetitious and replete with sweeping generalizations, unsubstantiated conclusions, and non sequiturs. The bulk of the work is an excursion in the history of modern philosophy that attempts to substantiate and amplify Solovyov’s justly famous claims, made in the opening lines, that: (i) philosophy — qua a body of abstract, purely theoretical knowledge — has finished its development; (ii) philosophy in this sense is no longer nor will it ever again be maintained by anyone; (iii) philosophy has bequeathed to its successor certain accomplishments or results that this successor will utilize to resolve the problems that philosophy has unsuccessfully attempted to resolve.

Solovyov tells us that his ambitious program differs from positivism in that, unlike the latter, he understands the superseded artifact called “philosophy” to include not merely its “speculative” but also its “empirical” direction. Whether these two directions constitute the entirety of modern philosophy, i.e., whether there has been any historical manifestation of another sense of philosophy, one that is not purely theoretical, during the modern era, is unclear. Also left unclear is what precisely Solovyov means by “positivism.” He mentions as representatives of that doctrine Mill, Spencer and Comte, whose views were by no means identical, and mentions as the fundamental tenet of positivism that “independent reality cannot be given in external experience.” This I take to mean that experience yields knowledge merely of things as they appear, not as they are “in themselves.” Solovyov has, it would seem, confused positivism with phenomenalism.

Solovyov’s reading of the development of modern philosophy proceeds along the lines of Hegel’s own interpretation. He sees Hegel’s “panlogism” as the necessary result of Western philosophy. The “necessity” here is clearly conceptual, although Solovyov implicitly accepts without further ado that this necessity has, as a matter of fact, been historically manifested in the form of individual philosophies. Moreover, in line with Hegel’s apparent self-interpretation Solovyov agrees that the former’s system permits no further development. For the latter, at least, this is because, having rejected the law of (non)contradiction, Hegel’s philosophy sees internal contradiction, which otherwise would lead to further development, as a “logical necessity,” i.e., as something the philosophy itself requires and is accommodated within the system itself.

Similarly, Solovyov’s analysis of the movement from Hegelianism to mid-19th century German materialism is largely indebted to the left-Hegelians. Solovyov, however, merely claims that one can exit Hegelianism by acknowledging its fundamental one-sidedness. Yet in the next breath, as it were, he holds that the emergence of empiricism, qua materialism, was necessary. Out of the phenomenalism of empiricism arises Schopenhauer’s philosophy and thence Eduard von Hartmann’s.

All representatives of Western philosophy, including to some extent Schopenhauer and von Hartmann, see rational knowledge as the decomposition of intuition into its sensuous and logical elements. Such knowledge, however, in breaking up the concrete into abstractions without re-synthesizing them, additionally is unable to recognize these abstractions as such but must hypostatize them, that is, assign real existence to them.. Nevertheless, even were we to grant Solovyov’s audacious thesis that all Western philosophers have done this abstraction and hypostatizing, it by no means follows that rational thought necessarily has had to follow this procedure.

According to Solovyov, von Hartmann, in particular, is aware of the one-sidedness of both rationalism and empiricism, which respectively single out the logical and the sense element in cognition to the exclusion of the other. Nevertheless, he too hypostatizes will and idea instead of realizing that the only way to avoid any and all bifurcations is through a recognition of what Solovyov terms “the fundamental metaphysical principle,” namely that the all- encompassing spirit is the truly existent. This hastily enunciated conclusion receives here no further argument. Nor does Solovyov dwell on establishing his ultimate claim that the results of Western philosophical development, issuing in the discovery of the all-encompassing spirit, agree with the religious beliefs of the Eastern Church fathers.

4. Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge

This work originally appeared during 1877 as a series of articles in an official journal published by the Ministry of Education (Zhurnal Ministerstva narodnogo prosveshchenija). Of Solovyov’s major writings it is probably the most difficult for the philosopher today to understand owing, to a large degree, to its forced trichotomization of philosophical issues and options and its extensive use of terms drawn from mystical sources even when employed in a quite different sense.

There are three fundamental aspects, or “subjective foundations,” of human life–in Solovyov’s terminology, “forms of being.” They are: feeling, thinking and willing. Each of these has both a personal and a social side, and each has its objective intentional object. These are, respectively, objective beauty, objective truth and the objective good. Three fundamental forms of the social union arise from human striving for the good: economic society, political society (government), and spiritual society. Likewise in the pursuit of truth there arises positive science, abstract philosophy, and theology. Lastly, in the sphere of feeling we have the technical arts, such as architecture, the fine arts and a form of mysticism, which Solovyov emphasizes is an immediate spiritual connection with the transcendent world and as such is not to be confused with the term “mysticism” as used to indicate a reflection on that connection.

Human cultural evolution has literally passed through these forms and done so according to what Solovyov calls “an incontestable law of development.” Economic socialism, positivism and utilitarian realism represent for him the highest point yet of Western civilization and, in line with his earlier work, the final stage of its development. But Western civilization with its social, economic, philosophic and scientific atomization represents only a second, transitional phase in human development. The next, final stage, characterized by freedom from all one- sidedness and elevation over special interests is presently a “tribal character” of the Slavic peoples and, in particular, of the Russian nation.

Although undoubtedly of some historical interest as an expression of and contribution to ideas circulating in Russia as to the country’s role in world affairs, Solovyov expounded all the above without argument and as such is of little interest to contemporary philosophy. Of somewhat greater value is his critique of traditional philosophical directions.

Developing its essential principle to the end, empiricism holds that I know only what the senses tell me. Consequently, I know even of myself only through conscious impressions, which, in turn, means that I am nothing but states of consciousness. Yet my consciousness presupposes me. Thus, we have found that empiricism leads, by reductio ad absurdum, to its self-refutation. The means to avoid such a conclusion, however, lies in recognizing the absolute being of the cognizing subject, which, in short, is idealism.

Likewise, the consistent development of the idealist principle leads to a denial of the epistemic subject and pure thought. The dissolution of these two directions means the collapse of all abstract philosophy. We are left with two choices: either complete skepticism or the view that what truly exists has an independent reality quite apart from our material world, a view Solovyov terms “mysticism.” With mysticism we have, in Solovyov’s view, exhausted all logical options. That is, having seen that holding the truly existing to be either the cognized object or the cognizing subject leads to absurdity, the sole remaining logical possibility is that offered by mysticism, which, thus, completes the “circle of possible philosophical views.” Although empiricism and rationalism (= idealism) rest on false principles, their respective objective contents, external experience, qua the foundation of natural science, and logical thought, qua the foundation of pure philosophy, are to be synthesized or encompassed along with mystical knowledge in “integral knowledge,” what Solovyov terms “theosophy.”

For whatever reason, Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge remained incomplete. Despite its expression of his own views, which undoubtedly at this stage were greatly indebted to the Slavophiles, Solovyov altered his original plan to submit this work as a doctoral dissertation. Instead, in April 1880 he defended at St. Petersburg University a large work that he had begun at approximately the same time as the Philosophical Principles and which, like the latter, appeared in serialized form starting in 1877 and as a separate book in 1880.

5. Critique of Abstract Principles

Originally planned to comprise three parts, ethics, epistemology and aesthetics, (which alone already reveals a debt to Kant) the completed work never turned to the last of these, on which, however, Solovyov labored extensively. Nevertheless, owing largely to its traditional philosophical style and its extended treatment of major historical figures, the Critique remains the most accessible of Solovyov’s major early writings today.

(1) Subjective Ethics. Over the course of human development a number of principles have been advanced in pursuit of various goals deemed to be that for which human actions should strive—goals such as pleasure, happiness, fulfilment of duties, adherence to God’s will, etc. Certainly seeking happiness, pleasure, or the fulfilment of duty is not unequivocally wrong. Yet the pursuit of any one of these alone without the others cannot provide a basis for a totally satisfactory ethical system. A higher synthesis or, if you will, a more encompassing unity is needed, one that will reveal how and when any of these particular pursuits is ethically warranted. Such a unity will show the truth, and thereby the error, of singling out any particular moment of the unity as sufficient alone. Doing so, that is, showing the proper place of each principle, showing them as necessary yet inadequate stages on the way to a complete synthetic system is what Solovyov means by “the critical method.”

In the end all moral theories that rest on an empirical basis, something factual in human nature, fail because they cannot provide and account for obligation. The essential feature of moral law, as Solovyov understands the concept, is its absolute necessity for all rational beings. The Kantian influence here is unmistakable and indubitable. Nevertheless, Solovyov parts company with Kant in expressing that a natural inclination in support of an obligatory action enhances the moral value of an action. Since duty is the general form of the moral principle, whereas an inclination serves as the psychological motive for a moral action, i.e., as the material aspect of morality, the two cannot contradict one another.

The Kantian categorical imperative, which Solovyov, in general, endorses, presupposes freedom. Of course, we all feel that our actions are free, but what kind of freedom is this? Here Solovyov approaches phenomenology in stating that the job of philosophy is to analyze this feeling with an eye to determining what it is we are aware of. Undoubtedly, for the most part we can do as we please, but such freedom is freedom of action. The question, however, is whether I can actually want something other than I do, i.e., whether the will is free.

Again like Kant, Solovyov believes all our actions, even the will itself, is, at least viewed empirically, subject to the law of causality. From the moral perspective, however, there is a “causality of freedom,” a freedom to initiate a causal sequence on the part of practical reason. In other words, empirically the will is determined, whereas transcendentally it is free. Solovyov, though, goes on to pose, at least rhetorically, the question whether this transcendental freedom is genuine or could it be that the will is subject to transcendental conditions. In doing so, he reveals that his conception of “transcendental” differs from that of Kant. Nevertheless, waving aside all difficulties associated with a resolution of the metaphysical issue of freedom of the will, Solovyov tells us, ethics has no need of such investigations; reason and empirical inquiry are sufficient. The criteria of moral activity lie in its universality and necessity, i.e., that the principle of one’s action can be made a universal law.

(2) Objective Ethics. In order that the good determine my will I must be subjectively convinced that the consequent action can be realized. This moral action presupposes a certain knowledge of and is conditioned by society. Subjective ethics instructs us that we should treat others not as means but as ends. Likewise, they should treat me as an end. Solovyov terms a community of beings freely striving to realize each other’s good as if it were his or her own good “free communality.” Although some undoubtedly see material wealth as a goal, it cannot serve as a moral goal. Rather, the goal of free communality is the just distribution of wealth, which, in turn, requires an organization to administer fair and equal treatment of and to all, in other words, a political arrangement or government. To make the other person’s good my good, I must recognize such concern as obligatory. That is, I must recognize the other as having rights, which my material interests cannot infringe.

If all individuals acted for the benefit of all, there would be no need for a coordination of interests, for interests would not be in conflict. There is, however, no universal consensus on benefits and often enough individually perceived benefits conflict. In this need for adjudication lies a source of government and law. Laws express the negative side of morality, i.e., they do not say what should be done, but what is not permitted. Thus, the legal order is unable to provide positive directives, precisely because what humans specifically should do and concretely aspire to attain remains conditional and contingent. The absolute, unconditional form of morality demands an absolute, unconditional content, namely, an absolute goal.

As a finite being, the human individual cannot attain the absolute except through positive interaction with all others. Whereas in the legal order each individual is limited by the other, in the aspiration or striving for the absolute the other aids or completes the self. Such a union of beings is grounded psychologically in love. As a contingent being the human individual cannot fully realize an absolute object or goal. Only in the process of individuals working in concert, forming a “total-unity,” does love become a non-contingent state. Only in an inner unity with all does man realize what Solovyov calls “the divine principle.”

Solovyov himself views his position as diametrically opposed to that of Kant, who from absolute moral obligation was led to postulating the existence of God, immortality and human freedom. For Solovyov, the realization of morality presupposes an affirmative metaphysics. Once we progress from Kant’s purely subjective ethics to an objective understanding of ethics, we see the need for a conviction in the theoretical validity of Kant’s three postulates, their metaphysical truth independent of their practical desirability.

Again differing from Kant, and Fichte too, Solovyov at this point in his life rejects the priority of ethics over metaphysics. The genuine force of the moral principle rests on the existence of the absolute order. And the necessary conviction in this order can be had only if we know it to be true, which demands an epistemological inquiry.

(3) Epistemology/Metaphysics. “To know what we should do we must know what is,” Solovyov tells us. To say “what is,” however, is informative only in contrast to saying, at least implicitly, “what is not” — this we already know from the opening pages of Hegel’s Logic. One answer is that the true is that which objectively exists independent of any knowing subject. Here Solovyov leads us down a path strikingly similar, at least in outline, to that taken in the initial chapters of Hegel’s Phenomenology. If the objectively real is the true, then sense certainty is our guarantee of having obtained it. But this certainty cannot be that of an individual knowing subject alone, for truth is objective and thus the same for everyone. Truth must not be in the facts but the things that make up the facts. Moreover, truth cannot be the individual things in isolation, for truths would then be isomorphic with the number of things. Such a conception of truth is vacuous; no, truth is one. With this Solovyov believes he has passed to naturalism.

Of course, our immediate sense experience lacks universality and does not in all its facets correspond to objective reality. Clearly, many qualities of objects, for example, color and taste, are subjective. Thus, reality must be what is general or present in all sense experience. To the general foundation of sensation corresponds the general foundation of things, namely, that conveyed through the sense of touch, i.e., the experience of resistance. The general foundation of objective being is its impenetrability.

Holding true being to be single and impenetrable, however, remains untenable. Through a series of dialectical maneuvers, reminiscent of Hegel, Solovyov arrives at the position that true being contains multiplicity. That is, whereas it is singular owing to absolute impenetrability, it consists of separate particles, each of which is impenetrable. Having in this way passed to atomism, Solovyov provides a depiction largely indebted to Kant’s Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. Solovyov recognizes that we have reached atomism, not through some experimental technique but through philosophical, logical reasoning. But every scientific explanation of the ultimate constituents of reality transgresses the bounds of experience. We return to the viewpoint that reality belongs to appearances alone, i.e., what is given in experience. Now, however, our realism has been dialectically transformed into a phenomenal or critical realism.

According to phenomenal realism, absolute reality is ultimately inaccessible to cognition. Nevertheless, that which cognitively is accessible constitutes a relative objectivity and is our sole standard for determining truth and thus knowledge. In this sensualism — for that is what it is — we refer particular sensations to definite objects. These objects are taken as objectively real despite the manifest subjectivity of sensation in general. Thus, objectification, as the imparting of the sense of objectivity onto the content of sensations, must be an independent activity of the cognizing subject.

Objectification, alone, cannot account for the definite object before me to which all my sensations of that object refer as parts or aspects. In addition to objectification there must be a unification or synthesizing of sensations, and this process or act is again distinct from sensing and certainly is not part of the sensation itself. Again evoking an image of Kant in the reader, Solovyov calls the independent cognitive act whereby sense data are formed into definite objective representations the imagination.

The two factors we have discerned, one contributed by the epistemic subject and the other by sensation, are absolutely independent of each other. Cognition requires both, but what connects them remains unanswered. According to Solovyov, any connection implies dependence, but the a priori element certainly cannot be dependent on the empirical. For, following Hume, from the factual we cannot deduce the universality and the necessity of a law. The other alternative is to have the content of true cognition dependent on the forms of reason; such is the approach of Hegel’s absolute rationalism. However, if all the determinations of being are created by cognition, then at the beginning we have only the pure form of cognition, pure thought, a concept of being in general. Solovyov finds such a starting point to be vacuous. For although Hegel correctly realizes the general form of truth to be universality, it is a negative conception from which nothing can be derived. The positive conception is a whole that contains everything in itself, not, as in Hegel, one that everything contains in itself.

For Solovyov, truth, in short, is the whole, and, consequently, each particular fact in isolation from the whole is false. Again Solovyov’s position on rationality bears an uncanny resemblance to that of Hegel, although in the former’s eyes this resemblance is superficial. Reason is the whole, and so the rationality of a particular fact lies in its interrelation with the whole. A fact divorced from the whole is irrational.

True knowledge implies the whole, the truly existent, the absolute. Following Solovyov’s “dialectical” thinking, the absolute, qua absolute, presupposes a non-absolute; one (or the whole) presupposes the many. And, again conjuring up visions of Hegel, if the absolute is the one, the non-absolute is becoming the one. The latter can become the one only if it has the divine element potentially. In nature, the one exists only potentially, whereas in humans it is actual, though only ideally, i.e., in consciousness.

The object of knowledge has three forms: 1) as it appears to us empirically, 2) as conceptually ideal, and 3) as existing absolutely independent of our cognition of it. Our concepts and sensations would be viewed merely as subjective states were it not for the third form. The basis for this form is a third sort of cognition, without which objective truth would elude us. A study of the history of philosophy correctly shows that neither the senses nor the intellect, whether separately or in combination, can satisfactorily account for the third form. Sensations are relative, and concepts conditional. Indeed, the referral of our thoughts and sensations to an object in knowledge, thus, presupposes this third sort of cognition. Such cognition, namely, faith or mystical knowledge, would itself be impossible if the subject and the object of knowledge were completely divorced. In this interaction we perceive the object’s essence or “idea,” its constancy. The imagination (here, let us recall Kant), at a non-conscious level, organizes the manifold given by sense experience into an object via a referral of this manifold to the “idea” of the object.

Solovyov believes he has demonstrated that all knowledge arises through the confluence of empirical, rational and “mystical” elements. Only philosophical analysis can discover the role of the mystical. Just as an isolation of the first two elements has historically led to empiricism and rationalism respectively, so the mystical element has been accentuated by traditional theology. And just as the former directions have given rise to dogmatic manifestations, so too has theology found its dogmatic exponents. The task before us lies in freeing the three directions of their exclusiveness, intentionally integrating and organizing true knowledge into a complete system, which Solovyov called “free theosophy.”

6. The Justification of the Good

After the completion of the works mentioned above, Solovyov largely withdrew from philosophy, both as a profession and its concerns. During the 1880s he devoted himself increasingly to theological and topical social issues of little, if any, concern to the contemporary philosopher. However, in 1894 Solovyov took to preparing a second edition of the Critique of Abstract Principles. Owing, though, to an evolution, and thereby significant changes, in his viewpoint, he soon abandoned this venture and embarked on an entirely new statement of his philosophical views. Just as in his earlier treatise, Solovyov again intended to treat ethical issues before turning to an epistemological inquiry.

The Justification of the Good appeared in book form in 1897. Many, though not all, of its chapters had previously been published in several well-known philosophical and literary journals over the course of the previous three years. Largely in response to criticisms of the book or its serialized chapters, Solovyov managed to complete a second edition, which was published in 1899 and accompanied by a new preface.

Most notably, Solovyov now holds that ethics is an independent discipline. In this he finds himself in solidarity with Kant, who made this “great discovery,” as Solovyov put it. Knowledge of good and evil is accessible to all individuals possessing reason and a conscience and needs neither divine revelation nor epistemological deduction. Although philosophical analysis surely is unable to instill a certainty that I, the analyst, alone exist, solipsism even if true would eliminate only objective ethics. There is another, a subjective side to ethics that concerns duties to oneself. Likewise, morality is independent of the metaphysical question concerning freedom of the will. From the independence of ethics Solovyov draws the conclusion that life has meaning and, coupled with this, we can legitimately speak of a moral order.

The natural bases of morality, from which ethics as an independent discipline can be deduced and which form the basis of moral consciousness, are shame, pity and reverence. Shame reveals to man his higher human dignity. It sets the human apart from the animal world. Pity forms the basis of all of man’s social relations to others. Reverence establishes the moral basis of man’s relation to that which is higher to himself and, as such, is the root of religion.

Each of the three bases, Solovyov tells us, may be considered from three sides or points of view. Shame as a virtue reveals itself as modesty, pity as compassion and reverence as piety. All other proposed virtues are essentially expressions of one of these three. The other two points of view, as a principle of action and as a condition of an ensuing moral action, are interconnected with the first such that the first logically contains the others.

Interestingly, truthfulness is not itself a formal virtue. Solovyov opposes one sort of extreme ethical formalism, arguing that making a factually false statement is not always a lie in the moral sense. The nature of the will behind the action must be taken into account.

Likewise, despite his enormous respect for Kant’s work in the field of ethics, Solovyov rejects viewing God and the immortality of the soul as postulates. God’s existence, he tells us, is not a deduction from religious feeling or experience but its immediate content, i.e., that which is experienced. Furthermore, he adds that God and the soul are “direct creative forces of moral reality.” How we are to interpret these claims in light of the supposed independence of ethics is contentious unless, of course, we find Solovyov guilty of simple-mindedness. Indeed one of his own friends [Trubeckoj] wrote: “It is not difficult to convince ourselves that these arguments about the independence of ethics are refuted on every later page in the Justification of the Good.” However we look upon Solovyov’s pronouncements, the Deity plays a significant role in his ethics. Solovyov provides a facile answer to the perennial question of how a morally perfect God can permit the existence of evil: Its elimination would mean the annihilation of human freedom thereby rendering free goodness (good without freedom is imperfect) impossible. Thus, God permits evil, because its removal would be a greater evil.

Often, all too often, Solovyov is prone to express himself in metaphysical, indeed theological, terms that do little to clarify his position. The realization of the Kingdom of God, he tells us, is the goal of life. What he means, however, is that the realization of a perfect moral order, in which the relations between individuals and the collective whole’s relations to each individual are morally correct, is all that can be rationally desired. Each of us understands that the attainment of moral perfection is not a solipsistic enterprise, i.e., that the Kingdom of God can only be achieved if we each want it and collectively attain it. The individual can attain the moral ideal only in and through society. Christianity alone offers the idea of the perfect individual and the perfect society. Other ideas have been presented (Solovyov mentions Buddhism and Platonism), of course, and these have been historically necessary for the attainment of the universal human consciousness that Christianity promises.

Man’s correct relations to God, his fellow humans and his own material nature, in accordance with the three foundations of morality – piety, pity (compassion) and shame – are collectively organized in three forms. The Church is collectively organized piety, whereas the state is collectively organized pity or compassion. To view the state in such terms already tells us a great deal concerning how Solovyov views the state’s mission and, consequently, his general stand toward laissez-faire doctrines. Although owing to the connection between legality and morality one can speak of a Christian state, this is not to say that in pre-Christian times the state had no moral foundations. Just as the pagan can know the moral law “written in his heart,” (an expression of St. Paul’s that Solovyov was fond of invoking but also reminiscent of Kant’s “the moral law within”) so too the pagan state has two functions: 1) to preserve the foundation of social life necessary for continued human existence, and 2) to improve the condition of humanity.

At the end of The Justification of the Good Solovyov attempts in the most cursory fashion to make a transition to epistemology. He claims that the struggle between good and evil raises the question of the latter’s origin, which in turn ultimately requires an epistemological inquiry. That ethics is an independent discipline does not mean that it is not connected to metaphysics and the theory of knowledge. One can study ethics in its entirety without first having answers to all other philosophical problems much as one can be an excellent swimmer without knowing the physics of buoyancy.

7. Theoretical Philosophy

During the last few years of his life Solovyov sought to recast his thoughts on epistemology. Surely he intended to publish in serial fashion the various chapters of a planned book on the topic, much as he did The Justification of the Good. Unfortunately at the time of his death in 1900 only three chapters were completed, and it is only on the basis of these that we can judge his new standpoint. Nevertheless, on the basis of these meager writings we can already see that Solovyov’s new epistemological reflections exhibit a greater transformation of his thoughts on the subject than does his ethics. Whereas a suggested affinity between these ideas and later German phenomenology must be viewed with caution and, in light of his earlier thoughts, a measure of skepticism, there can be little doubt that to all appearances Solovyov spoke and thought in this late work in a philosophical idiom close to that with which we have become familiar in the 20th century.

For Solovyov epistemology concerns itself with the validity of knowledge in itself, that is, not in terms of whether it is useful in practice or provides a basis for an ethical system that has for whatever reason been accepted. Perhaps not surprisingly then, particularly in light of his firm religious views, Solovyov adheres to a correspondence theory, saying that knowledge is the agreement of a thought of an object with the actual object. The open questions are how such an agreement is possible and how do we know that we know.

The Cartesian “I think, therefore I am” leads us virtually nowhere. Admittedly the claim contains indubitable knowledge, but it is merely that of a subjective reality. I might just as well be thinking of an illusory book as of an actually existing one. How do we get beyond the “I think”? How do we distinguish a dream from reality? The criteria are not present in the immediacy of the consciously intended object. To claim as did some Russian philosophers in his own day that the reality of the external world is an immediately given fact appears to Solovyov an arbitrary opinion hardly worthy of philosophy. Nor is it possible to deduce from the Cartesian inference that the I is a thinking substance. Here is the root of Descartes’ error. The self discovered in self-consciousness has the same status as the object of consciousness, i.e., both have phenomenal existence. If we cannot say what this object of my consciousness is like in itself, i.e., apart from my conscious acts, so too we cannot say what the subject of consciousness is apart from consciousness and for the same reason. Likewise, just as we cannot speak about the I in itself, so too we cannot answer to whom consciousness belongs.

In “The Reliability of Reason,” the second article comprising the Theoretical Philosophy, Solovyov concerns himself with affirming the universality of logical thought. In doing so he stands in opposition to the popular reductionisms, e.g., psychologism, that sought to deny any extra-temporal significance to logic. Thought itself, Solovyov tells us, requires recollection, language and intentionality. Since any logical thought is, nevertheless, a thought and since thought can be analyzed in terms of psychic functions, one could conceivably charge Solovyov with lapsing back into a psychologism, in precisely the same way as some critics have charged Husserl with doing so. And much the same defenses of Husserl’s position can also be used in reply to the objection against Solovyov’s stance.

The third article, “The Form of Rationality and the Reason of Truth,” published in 1898, concerns itself with the proper starting points of epistemology. The first such point is the indubitable veracity of the given in immediate consciousness. There can be no doubt that the pain I experience upon stubbing my toe is genuine. The second starting point of epistemology is the objective, universal validity of rational thought. Along with Hume and Kant, Solovyov does not dispute that factual experience can provide claims only to conditional generality. Rationality alone provides universality. This universality, however, is merely formal. To distinguish the rational form from the conditional content of thought is the first essential task of philosophy. Taking up this challenge is the philosophical self or subject. Solovyov concludes, again as he always does, with a triadic distinction between the empirical subject, the logical subject and the philosophical subject. And although he labels the first the “soul,” the second the “mind” and the third the “spirit,” the trichotomy is contrived and the labeling, at best, imaginative with no foundation other than in Solovyov’s a priori architectonic.

8. Concluding Remarks

Solovyov’s relatively early death, brought on to some degree by his erratic life-style, precluded the completion of his last philosophical work. He also intended to turn his attention eventually towards aesthetics, but whether he would ever have been able to complete such a project remains doubtful. Solovyov was never at any stage of his development able to complete a systematic treatise on the topic, although he did publish a number of writings on the subject.

However beneficial our reading of Solovyov’s works may be, there can be little doubt that he was very much a 19th-century figure. We can hardly take seriously his incessant predilection for triadic schemes, far in excess to anything similar in the German Idealists. His choice of terminology, drawn from an intellectual fashion of his day, also poses a formidable obstacle to the contemporary reader.

Lastly, despite, for example, an often perspicacious study of his philosophical predecessors, written during his middle years, Solovyov, in clinging obstinately to his rigid architectonic, failed to penetrate further than they. Indeed, he often fell far short of their achievements. His discussion of imagination, for example, as we saw, is much too superficial, adding nothing to that found in Kant. These shortcomings, though, should not divert us from recognizing his genuinely useful insights.

After his death, with interest surging in the mystical amid abundant decadent trends, so characteristic of decaying cultures, Solovyov’s thought was seized upon by those far less interested in philosophical analysis than he was towards the end. Those who invoked his name so often in the years immediately subsequent to his death stressed the religious strivings of his middle years to the complete neglect of his final philosophical project, let alone its continuation and completion. In terms of Solovyov-studies today the philosophical project of discovering the “rational kernel within the mystical shell” [Marx], of separating the “living from the dead” [Croce], remains not simply unfulfilled but barely begun.

9. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

- Sobranie sochinenij, St. Petersburg: Prosveshchenie, 1911-14.

- Sobranie sochinenij, Brussels: Zhizn s Bogom, 1966-70.ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS

- The Crisis of Western Philosophy (Against the Positivists), trans. by Boris Jakim, Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1996.

- Lectures on Divine Humanity, ed. by Boris Jakim, Lindisfarne Press, 1995.

- The Justification of the Good, trans. by N. Duddington, New York: Macmillan, 1918.

- “Foundations of Theoretical Philosophy,” trans. by Vlada Tolley and James P. Scanlan, in Russian Philosophy, ed. James

- M. Edie, et al., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965, vol. III, pp. 99-134.

b. Secondary Sources (mentioned above)

- Helmut Dahm, Vladimir Solovyev and Max Scheler: Attempt at a Comparative Interpretation, Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1975.

- Zdenek V. David, “The Influence of Jacob Boehme on Russian Religious Thought,” Slavic Review, 21(1962), 1, pp. 43-64.

- Aleksej Losev, Vladimir Solov’ev, Moscow: Mysl’, 1983.

- Ludolf Mueller, Solovjev und der Protestantismus, Freiburg: Verlag Herder, 1951.

- Joseph L. Navickas, “Hegel and the Doctrine of Historicity of Vladimir Solovyov,” in The Quest for the Absolute, ed.

- Frederick J. Adelmann, The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1966, pp. 135-154.

- Louis J. Shein, “V.S. Solov’ev’s Epistemology: A Re-examination,” Canadian Slavic Studies, Spring 1970, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1-16.

- E. N. Trubeckoj, Mirosozercanie V. S. Solov’eva, 2 vols., Moscow: Izdatel’stvo “Medium,” 1995,

- Aleksandr I. Vvedenskij, “O misticizme i kriticizme v teorii poznanija V. S. Solov’eva,” Filosofskie ocherki, Prague: Plamja, 1924, pp. 45-71.

Author Information

Thomas Nemeth

Email: t_nemeth@yahoo.com

U. S. A.