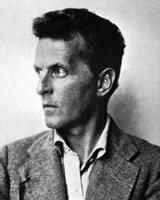

Wittgenstein: Epistemology

Although Ludwig Wittgenstein is generally more known for his works on logic and on the nature of language, but throughout his philosophical journey he reflected extensively also on epistemic notions such as knowledge, belief, doubt, and certainty. This interest is more evident in his final notebook, published posthumously as On Certainty (1969, henceforth OC), where he offers a sustained and, at least apparently, fragmentary treatment of epistemological issues. Given the ambiguity and obscurity of this work, written under the direct influence of G. E. Moore’s A Defense of Commonsense (1925, henceforth DCS) and Proof of an External World (1939, henceforth PEW), in the recent literature on the subject, we can find a number of competing interpretations of OC; at first, this article presents the uncontentious aspects of Wittgenstein’s views on skepticism, that is, his criticisms against Moore’s use of the expression “to know” and his reflections on the artificial nature of the skeptical challenge. Then it introduces the elusive concept of “hinges,” central to Wittgenstein’s epistemology and his views on skepticism; and it offers an overview of the dominant “Wittgenstein-inspired” anti-skeptical strategies along with the main objections raised against these proposals. Finally, it briefly sketches the recent applications of Wittgenstein’s epistemology in the contemporary debate on skepticism.

Although Ludwig Wittgenstein is generally more known for his works on logic and on the nature of language, but throughout his philosophical journey he reflected extensively also on epistemic notions such as knowledge, belief, doubt, and certainty. This interest is more evident in his final notebook, published posthumously as On Certainty (1969, henceforth OC), where he offers a sustained and, at least apparently, fragmentary treatment of epistemological issues. Given the ambiguity and obscurity of this work, written under the direct influence of G. E. Moore’s A Defense of Commonsense (1925, henceforth DCS) and Proof of an External World (1939, henceforth PEW), in the recent literature on the subject, we can find a number of competing interpretations of OC; at first, this article presents the uncontentious aspects of Wittgenstein’s views on skepticism, that is, his criticisms against Moore’s use of the expression “to know” and his reflections on the artificial nature of the skeptical challenge. Then it introduces the elusive concept of “hinges,” central to Wittgenstein’s epistemology and his views on skepticism; and it offers an overview of the dominant “Wittgenstein-inspired” anti-skeptical strategies along with the main objections raised against these proposals. Finally, it briefly sketches the recent applications of Wittgenstein’s epistemology in the contemporary debate on skepticism.

Table of Contents

- Wittgenstein on Radical Skepticism: A Minimal Reading

- The Therapeutic Reading

- The Epistemic Reading

- The Contextualist Reading

- The Non-epistemic Reading

- The Non-propositional Reading

- The Framework Reading

- Concluding Remarks

- References and Further Reading

1. Wittgenstein on Radical Skepticism: A Minimal Reading

The feature of Cartesian-style arguments is that we cannot know certain empirical propositions (such as “Human beings have bodies,” or “There are external objects”) as we may be dreaming, hallucinating, deceived by a demon, or be “brains in the vat” (BIV), that is, disembodied brains floating in a vat, connected to supercomputers that stimulate us in just the same way that normal brains are stimulated when they perceive things in a normal way. Therefore, as we are unable to refute these skeptical hypotheses, we are also unable to know propositions that we would otherwise accept as being true if we could rule out these scenarios.

Cartesian arguments are extremely powerful as they rest on the Closure principle for knowledge. According to this principle, knowledge is “closed” under known entailment. Roughly speaking, this principle states that if an agent knows a proposition (for example, that she has two hands), and competently deduces from this proposition a second proposition (for example, that having hands entails that she is not a BIV), then she also knows the second proposition (that she is not a BIV). More formally

The “Closure” Principle:

If a subject S knows that p, and p entails q, then S knows that q.

Let’s take a skeptical hypothesis, SH, such as the BIV hypothesis mentioned above, and M, an empirical proposition such as “Human beings have bodies” that would entail the falsity of a skeptical hypothesis. We can then state the structure of Cartesian skeptical arguments as follows:

(S1) I do not know not-SH

(S2) If I do not know not-SH, then I do not know M

(SC) I do not know M

Considering that we can repeat this argument for each and every one of our empirical knowledge claims, the radical skeptical consequence we can draw from this and similar arguments is that our knowledge is impossible.

A way of dealing with “Cartesian-style” skepticism is to affirm, contra the skeptic, that we can know the falsity of the relevant skeptical hypothesis; for instance, in DCS and PEW, G. E. Moore famously argued that we can have knowledge of the “commonsense view of the world,” that is of statements such as “Human beings have bodies,” “There are external objects,” or “The earth existed long before my birth” and that this knowledge would offer a direct response against skeptical worries.

Moore himself (1942) was not fully convinced by the anti-skeptical strength of DCS and PEW, which have engendered a huge debate that will be impossible to summarize here (see Malcolm, 1949; Clarke, 1973; Stroud, 1984). Nonetheless, it is important to notice that Moore’s affirmation that he knows for certain the “obvious truisms of the commonsense” is pivotal in his anti-skeptical strategy; his knowledge-claims would allow him to refute the skeptic.

But, argues Wittgenstein, to say that we know “obvious truisms” such as “There are external objects” is misleading for a number of reasons. First, because in order to claim “I know,” one should be able to, at least in principle, produce evidence or offer compelling grounds for her beliefs. That is to say, the “language-game” of knowledge involves and presupposes the ability to give reasons, justifications, and evidence; but crucially (OC 245), Moore’s grounds are not stronger than what they are supposed to justify. In other words, as per Wittgenstein, if a set of evidence has to count as compelling grounds for our belief in a certain proposition, then that evidence must be more certain than the belief itself; this cannot happen in the case of Moore’s “obvious truisms” because, at least in normal circumstances, nothing is more certain than the fact that we have two hands or a body (OC 125).

Just imagine, for instance, that one attempted to legitimate one’s claim to know that p by using the evidence that one has for p (that is, what one sees, what one has been told about p and so on). Now, if the evidence we adduce to support p is less certain than p itself, then this same evidence would be unable to support p.

However, Wittgenstein argues that if it would be somewhat odd to claim that we still know Moore’s “obvious truisms,” they cannot be an object of doubt. For instance, if someone is seriously pondering whether she has a body or not, we would not investigate the truth-value of her affirmations; rather, we would question her ability to understand the language she is using or her sanity, for a similar false belief would probably be the result of a sensorial or mental disturbance (OC 526).

Moreover, for Wittgenstein, the kind of never-ending doubt put forward by a proponent of radical skepticism, far from being a legitimate intellectual enterprise, will prevent his proponents from engaging in any intellectual activity at all; to support his point, Wittgenstein gives the example (OC 310) of a pupil who constantly interrupts a lesson, questioning the existence of things or the meanings of words. His doubts will lack any sense, and at most they will lead him to a sort of epistemic paralysis; he will just be unable to learn the skill/subject we are trying to teach him (OC 315).

More generally, for Wittgenstein, any proper epistemic inquiry presupposes that we take something for granted; if we start doubting everything, there will be no knowledge at all. As he remarks at one point:

If you are not certain of any fact, you cannot be certain of the meaning of your words either […] If you tried to doubt everything you would not get as far as doubting anything. The game of doubting itself presupposes certainty (OC 114–115).

That is to say, the questions that we raise and our doubts depend on the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were like hinges on which those turn […] But it isn’t that the situation is like this: We just can’t investigate everything, and for that reason we are forced to rest content with assumption. If I want the door to turn, the hinges must stay put (OC 341–343).

Neither knowable nor doubtable, for Wittgenstein, Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” are “hinges” (OC 341–343): apparently empirical contingent beliefs which perform a different, basic role in our epistemic practices.

2. The Therapeutic Reading

The “therapeutic reading” of OC (Conant, 1998) stems from the remarks in which Wittgenstein talks about Moore’s “misuse” of the expression “to know”:

Now, can one enumerate what one knows (like Moore)? Straight off like that, I believe not. For otherwise the expression “I know” gets misused. And through this misuse a queer and extremely important mental state seems to be revealed (OC 6).

I know that a sick man is lying here? Nonsense! I am sitting at his bedside, I am looking attentively into his face. So I don’t know, then, that there is a sick man lying here? Neither the question nor the assertion makes sense. Any more than the assertion “I am here”, which I might yet use at any moment, if suitable occasion presented itself. […] And “I know that there’s a sick man lying here”, used in an unsuitable situation, seems not to be nonsense but rather seems matter-of-course, only because one can fairly easily imagine a situation to fit it, and one thinks that the words “I know that…” are always in place where there is no doubt, and hence even where the expression of doubt would be unintelligible (OC 10).

According to the proponents of the “therapeutic reading,” we should read these passages in light of the theory, pivotal in later Wittgensteinian thought, that the meaning of a word consists in its use in ordinary situations. As he writes in his Philosophical Investigations (1997, henceforth PI):

For a large class of cases—though not for all—in which we employ the word “meaning” it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language (PI 43).

This would allow us to reconstruct Wittgenstein’s treatment of skepticism as follows. Moore fails to mean something quite particular by stating his “obvious truisms” outside of a language-game, that is outside any of our everyday epistemic practices; thus, in the circumstances in which they are actually used, it is not clear what has been said, if anything.

At the same time, a radical skeptic fails to recognize the role—or, using Wittgenstein’s expression, the use—that expressions such as “knowledge” and “doubt” play in our ordinary epistemic practices; as in our everyday life there is nothing similar to the kind of general investigation pursued by the radical skeptic (OC 209 “A doubt without an end is not even a doubt.”), the skeptical challenge would be, strictly speaking, senseless (1998, 241–248).

Following the therapeutic reading of OC, then, both Cartesian skepticism and Moore’s anti-skeptical strategy would be based on a misunderstanding of how language works; it is not clear what Moore and the skeptic are doing with their words and therefore, even if apparently they have a meaning, they lack any sense.

This rendering of Wittgenstein’s anti-skeptical position has appeared to many commentators (see, for instance, Salvatore, 2013) to be simply too crude.

Consider the following entries:

The statement “I know that here is a hand” may then be continued: “for its my hand that I am looking at”. Then a reasonable man will not doubt that I know. Nor will the idealist; rather he will say that he was not dealing with the practical doubt which is being dismissed, but there is a further doubt behind that one. That this is an illusion has to be shewn in a different way (OC 19). But it is an adequate answer to the skepticism of the idealist, or the assurances of the realist, to say that ‘There are physical objects’ is nonsense? For them after all it is not nonsense. It would, however, be an answer to say: this assertion, or its opposite, it’s a misfiring attempt to express what can’t be expressed like that. And that it does misfire can be shewn; but that isn’t the end of the matter. We need to realize that what presents itself to us as the first expression of a difficulty, or of its solution, may as yet not be correctly expressed at all. Just as one who has a just censure of a picture to make will often at first offer the censure where it does not belong, and an investigation is needed in order to find the right point of attack for the critic (OC 37).

These remarks alone seem to suggest that Wittgenstein was well aware that simply showing that the skeptic was using terms such as “knowledge” and “doubt” outside of any ordinary practice was not enough to dismiss skeptical worries. On the contrary, he seems to concede that nothing prevents us from thinking that the skeptic and his opponent are engaged in a “language-game,” that is philosophical inquiry, in which the expressions “to know” and “to doubt” are used in a way that is at odds with their everyday usage but is still, at least apparently, meaningful and legitimate.

Also, these passages show that Wittgenstein would not consider a rebuttal of skepticism on the basis of pragmatic considerations alone to be satisfactory. Recall that on Conant’s reading, Wittgenstein would dismiss skeptical doubts as they are at odds with our ordinary practices, thus unintelligible on closer inspection; on the contrary, he stresses the necessity for a philosophical analysis of the hidden assumptions that make the skeptical “doubt” so apparently compelling.

3. The Epistemic Reading

A very influential reading of OC is Crispin Wright’s notion of “rational entitlement” (2004a/2004b), which stems from his famous diagnosis of Moore’s Proof (1985). If in DCS, as we have already seen, Moore argued that we can have knowledge of the “commonsense view of the world,” that is of very general “obvious truisms” such as “I am a human being,” “Human beings have bodies,” “The earth existed long before my birth,” and so on, in PEW, he famously maintained that even an instance of everyday knowledge such as “This is a hand” can offer a direct response against skeptical worries. Moore’s Proof is standardly rendered as follows:

(MP 1) Here is a hand

(MP 2) If there is a hand here, then there are external objects

(MP C) There are external objects

As per Wright, we can reconstruct PEW as follows:

- I. It perceptually appears to me that there are two hands

- II. There are two hands

- III. Therefore, there are material objects

In other words, to state I) amounts to saying that there is a proposition that correctly describes the relevant aspects of Moore’s experience in the circumstances in which the Proof was given; in the case of the Proof, for instance, I) will sound like “I am perceiving (what I take to be) my hand.” Then, from I) follows II) and from II) follows III), since “a hand” is a physical object; and given that the premises are known, so is the conclusion.

But, argues Wright, the passage from I) to II) is highly problematic: if Moore was victim of a skeptical scenario such as the “Dream hypothesis” and thus was just dreaming his hand, II) would no longer follow from I). More generally, I) can ground II) only if we already take for granted that our experience is caused by our interaction with material objects; thus, sensory experience can warrant a belief about empirical objects only if we already assume that there are material objects.

Hence, we need to already have a warrant for III) in order to justifiably go from I) to II); and this is why Moore’s Proof would be question begging or epistemically circular: in order to consider the premises of Moore’s Proof true, we are implicitly assuming the truth of its conclusion.

Thus, Moore’s Proof would lead to another, more subtle form of skepticism that Wright calls Humean ; while Cartesian-style skepticism goes from uncongenial skeptical scenarios to show that we cannot know any of our empirical beliefs, Humean skepticism argues that anytime we make an empirical knowledge claim, we are already assuming that, so to say, things outside of us are already the way we take them to be and, more generally, that there are material objects.

Again, in order to go from I) to II) to III), we need to have an independent warrant to believe that III) is true; and as we do not have this independent warrant, then the argument fails to provide warrant for his conclusions. This is a phenomenon that Wright calls “failure of transmission of warrant” (or transmission failure for short). However, Wright argues, in many cases our inquiries are based on commitments or presuppositions that cannot be justified, but that nonetheless we take for granted whenever we are involved in an epistemic practice; and this is what happens with Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense.” On Wright’s account, “hinges” are beliefs whose rejection would rationally necessitate extensive reorganization, or the complete destruction, of what should be considered as empirical evidence or more generally of our epistemic practices.

This reading of OC leads Wright to propose the following “Wittgenstein-inspired” anti-skeptical account. Each and every one of our ordinary inquiries would then rest on ungrounded presuppositions, “hinges”; but still, argues Wright, since the warrant to hold Moore’s “obvious truisms” is acquired in an epistemically responsible way, we cannot dismiss them simply because they are groundless as this would lead to a complete cognitive paralysis (2004a, 191).

As per Wright, then, Cartesian skepticism would only show that every process of knowledge-acquisition rests on ungrounded presupposition. However, a system of thought, purified of all liability to hinges, would not be that of a rational agent; and because rational agency is a basic way for us to act, we therefore have a default rational basis, an entitlement, to believe in “hinges” and thus to know them, even if in an unwarranted way (hence “epistemic reading”).

Wright’s rational entitlement has engendered a huge debate that would be impossible to summarize here (see Pryor 2000, 2004, 2012; Davies 2003, 2004; Coliva, 2009a, 2009b, 2015). This article presents only the main objections raised against the plausibility of the “epistemic reading” and its anti-skeptical strength.

A first issue (Salvatore, 2013) is that following this account, the Cartesian skeptical challenge, even if ultimately illegitimate, would nonetheless have the merit to highlight a constitutive limit of our epistemic practices, namely that they rest on ungrounded presuppositions. On the contrary, far from revealing the structure of our epistemic practices, for Wittgenstein, Cartesian-style skepticism will undermine the same notion of what an epistemic practice is. For once we doubt a hinge such as “There are external objects,” expressions like “evidence,” “justification,” and “doubt” will radically alter if not completely lose their meaning. Wittgenstein stresses this point in many entries of OC, as in the following remark, where he writes:

If, therefore, I doubt or am uncertain about this being my hand (in whatever sense), why not in that case about the meaning of these words as well? (OC 456).

That is to say, once we assume ex hypothesis that we could be victims of a skeptical scenario, it would be hard to understand what could count as evidence for what, as each and every one of our perceptions would be the result of constant deception. Thus, to doubt a hinge would put in question the same meaning of the words with which we are expressing our doubts.

Another objection against Wright’s proposal goes as follows. Recall that, for Wright, we are rationally entitled to believe in the truth of hinges such as “Human beings have bodies” or “There are external objects.” A consequence of this thought (Pritchard, 2005) is that following this strategy, it would be possible to know the denials of skeptical hypotheses, even if in an unwarranted way: an anti-skeptical move which is excluded by Wittgenstein in many remarks of OC, as in the following entries:

Moore has every right to say he knows there’s a tree there in front of him. Naturally he may be wrong. (For it is not the same as with the utterance “I believe there is a tree there”.) But whether he is right or wrong in this case is of no philosophical importance. If Moore is attacking those who say that one cannot really know such a thing, he can’t do it by assuring them that he knows this and that […] (OC 520).

Moore’s mistake lies in this—countering the assertion that one cannot know that, by saying “I do know it” (OC 521).

That is to say, to claim against a Cartesian skeptic that we know Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” would be at the same time misleading and unconvincing.

First, as we have already seen “hinges” cannot be evidentially grounded, for any evidence, we could adduce to support a proposition p such as “I have a hand” would be less secure than p itself. As Wittgenstein writes at some point:

One says “I know” when one is ready to give compelling grounds. “I know” relates to a possibility of demonstrating the truth. Whether someone knows something can come to light, assuming that he is convinced of it. But if what he believes is of such a kind that the grounds he can give are no surer than his assertion, than he cannot say that he knows what he believes (OC 243).

Also, and more importantly, to claim that we “know” Moore’s “‘obvious truisms of the commonsense” on the basis of pragmatic considerations would simply miss the point of the skeptical challenge.

Moreover (Pritchard, 2005; Jenkins, 2007) following Wright, it is entirely rational to set aside skeptical concerns whenever we want to pursue a given epistemic practice; but here Wright seems to conflate practical and epistemic rationality. That is to say, a Cartesian skeptic can well agree that we have to dismiss skeptical concerns whenever we are involved in a given epistemic inquiry, as not to do so would lead to a cognitive paralysis. But even conceding that it would be practically rational to set aside skeptical worries in order to achieve cognitive results, what is at issue in the skeptical challenge is the epistemic rationality of trusting our senses when skeptical hypotheses are in play. In other words, a skeptic can grant that we have to rule out skeptical worries when we need to form true beliefs about the world in our everyday life; still, she can argue that the fact that we need true beliefs about the world does not make our acceptance of “hinges” epistemically rational as long as we cannot rule out skeptical scenarios. Wittgenstein himself was well aware of this point; consider OC 19:

The statement “I know that here is a hand” may then be continued: “for its my hand that I am looking at”. Then a reasonable man will not doubt that I know. Nor will the idealist; rather he will say that he was not dealing with the practical doubt which is being dismissed, but there is a further doubt behind that one. That this is an illusion has to be shewn in a different way.

4. The Contextualist Reading

Another influential reading of OC is Michael Williams’ “Wittgensteinian Contextualism” which he has proposed in his book Unnatural Doubts and in a number of other more recent works (1991, 2001, 2004a, 2004b, 2005). A first formulation of a contextualist interpretation of OC can be found in Morawetz (1978). (For a general introduction to epistemic contextualism, along with an overview of other “non Wittgensteinian” contextualist anti-skeptical proposals, see here.)

Recall that in some passages of OC (OC 114, 115, 315, 322), Wittgenstein argues that any proper inquiry presupposes certainty, that is, some unquestionable prior commitment. In these remarks, Wittgenstein also alludes to the importance of the context of inquiry; hence stating that without a precise context, there is no possibility of raising a sensible question or a doubt. Williams generalizes this part of Wittgenstein’s argument as follows: in each context of inquiry, there is necessarily a set of “hinge” beliefs (that he names methodological necessities), which will hold fast and which are therefore immune to epistemic evaluation in that context.

A motivation for this reading is the extreme heterogeneity of the “hinges” mentioned by Wittgenstein. Along with Moore’s “obvious truisms,” in fact, throughout OC he considers as “hinges” propositions whose certainty is indexed to a historical period (“No man has ever been on the moon.”) together with basic mathematical truths (“12 × 12 = 144”) and contingently empirical claims (“This is a hand.”). As per Williams, this would be a way to stress a basic feature of our inquiries: namely, they all would rest on unsupported presuppositions that can nevertheless be dismissed/questioned where new questions arise or when we are switching from a context of inquiry to another. For instance, a historical inquiry about whether, say, Napoleon won at Austerlitz presupposes “hinge commitments” such as “The world existed long before my birth”; all our everyday epistemic practices presuppose hinges such as “There are external objects” or “Human beings have bodies,” and so on.

Crucially, for Williams to take for granted the “methodological necessities” of a given epistemic practice is not only a matter of practical rationality as in Wright’s “entitlement strategy”; rather, it is a condition of possibility of any sensible enquiry. That is to say, while following Wright, we have to rest on “hinges” mostly because it is the only practical alternative, for Williams our confidence in Moore’s “obvious truisms” would highlight the constitutively “local” and “context-dependent” nature of all our epistemic practices.

Thus, in ordinary contexts, it would be illegitimate to doubt hinges such as “Human beings have bodies” or “There are external objects”; but once these are brought into focus, for instance by running skeptical arguments, we are simply switching from a context of inquiry to another, that is, from the everyday context into the philosophical one.

Therefore, by doubting the “hinges” of our most common epistemic practices, the skeptic is simply leading us from a context in which it is legitimate to hold these hinges fast toward a philosophical one in which everything can be doubtable.

Nonetheless, the skeptical move cannot affect our everyday knowledge claims, which are made by taken-for-granted “methodological necessities” such as “The earth existed long before my birth” or “Human beings have bodies.” At most, what the Cartesian skeptic is able to show us is that, in the more demanding context of philosophical reflection, we do not know, strictly speaking, anything at all.

A consequence of this thought is that, even if legitimate and constitutively unsolvable at a philosophical level, the Cartesian skeptical challenge would not affect our everyday epistemic practices as they belong to different contexts, with completely different methodological necessities or “hinges.” Moreover, the same propositions that we cannot claim to know at a philosophical level are known to be true, albeit tacitly, in other contexts even if they lack evidential support. Evidential support is something that they cannot constitutively possess, insofar as any hinge has to be taken for granted whenever we are involved in an epistemic practice.

There are many problems that Williams’ “Wittgensteinian contextualism” has to face in order to be considered a plausible interpretation of Wittgenstein’s thought. First, on his account, the skeptical enterprise is both completely legitimate and constitutively unsolvable. That is to say, in the context of our ordinary epistemic practices, it would be illegitimate to doubt “obvious truisms” such as “Human beings have bodies” or “This is a hand”; nonetheless, “hinges” would still be doubtable and dismissible in the more demanding context of philosophical inquiry.

Even if in some passages of OC, as we have seen while discussing the “therapeutic reading,” Wittgenstein seems to concede that a skeptic might be using the expressions “to know” and “to doubt” in a specialized and, so to say, “philosophical” way, this does not lead him to admit that the skeptic would be somewhat “right,” even if only in the philosophical context. Rather, throughout OC, Wittgenstein stresses that there is no context in which we can rationally hold a doubt about Moore’s “obvious truisms”; as we have seen supra, to seriously doubt a “hinge” would look more similar to a sign of mental illness than to a legitimate philosophical inquiry:

In certain circumstances a man cannot make a mistake. (Can here is used logically, and the proposition does not mean that a man cannot say anything false in those circumstances.) If Moore were to pronounce the opposite of those propositions which he declares certain, we should not just not share his opinion: we should regard him as demented (OC 155).

If I now say “I know that the water in the kettle in the gas-flame will not freeze but boil”, I seem to be as justified in this “I know” as I am in any. “If I know anything I know this”. Or do I know with still greater certainty that the person opposite me is my old friend so-and-so? And how does that compare with the proposition that I am seeing with two eyes and shall see them if I look in the glass? I don’t know confidently what I am to answer here. But still there is a difference between cases. If the water over the gas freezes, of course I shall be as astonished as can be, but I shall assume some factor I don’t know of, and perhaps leave the matter to physicists to judge. But what could make me doubt whether this person here is N.N., whom I have known for years? Here a doubt would seem to drag everything with it and plunge it into chaos (OC 613, my italics).

Thus, even if Wittgenstein seems somewhat to concede a prima facie plausibility to skeptical hypotheses, he nonetheless denies Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” can be sensibly doubted or denied, even if only in the context of philosophical inquiry (cfr. OC 231, 234).

Also, for Williams (2004a), Wittgenstein’s treatment of Moore’s “obvious truisms” would differ sensibly throughout OC; while the “hinges” listed by Moore would be “methodological necessities,” a statement such as “There are external objects,” namely the conclusion of PEW, would be plain nonsense (2004a, 86–87).

OC would then present two different anti-skeptical strategies, influenced respectively by Moore’s PEW and DCS. The first 60 entries of OC would be concerned with Moore’s Proof. On Williams’ reading, in these remarks, Wittgenstein would consider the skeptical challenge and Moore’s anti-skeptical strategy as constitutively senseless; both Moore and the skeptic would, in fact, treat “There are external objects” as a hypothesis that can be either confirmed by evidence or dismissed. But “There are external objects” is not an empirical hypothesis that can be tested or doubted; the very fact that we think, talk, and make judgments about the world shows that “There are external objects” and so any attempt to prove or to doubt this “proposition” would be misguided.

Williams motivates this division also to make sense of Wittgenstein’s saying that “There are external objects” is nonsense, but (Moyal-Sharrock, 2004, 91–92) Wittgenstein does not necessarily use the term nonsense in a derogatory way. Just consider this passage of the Philosophical Grammar (1974, henceforth PG):

[…] when we hear the two propositions, “This rod has a length” and its negation “This rod has no length”, we take sides and favor the first sentence, instead of declaring them both nonsense. But this partiality is based on a confusion; we regard the first proposition as verified (and the second as falsified) by the fact “that rod has a length of 4 meters” (PG 129).

For Wittgenstein, then, nonsense is not only what violates sense, but also what defines or elucidates it. Thus, Wittgenstein calls “There are physical objects” nonsense; still, this does not amount to saying that it is unintelligible or senseless. Also, while it is undeniable that, for Wittgenstein, “There are external objects” cannot be treated as a hypothesis, there is no clear suggestion that he would consider other “hinges” as open to doubt or verification . Consider the following entry:

It is clear that our empirical propositions do not all have the same status, since one can lay down such a proposition and turn it from an empirical proposition into a norm of description. Think of chemical investigations. Lavoisier makes experiments with substances in his laboratory and now he concludes that this and that takes place when there is burning. He does not say that it might happen otherwise another time. He has got hold of a definite world-picture—not of course one that he invented: he learned it as a child. I say world-picture and not hypothesis, because it is the matter-of-course foundation for his research and as such also does unmentioned (OC 167, my italics).

5. The Non-epistemic Reading

If for Wright and Williams, it is then possible to know hinges such as “There are external objects” or “Human beings have bodies,” whether out of practical considerations or in the context of our ordinary epistemic practices; according to the proponents of the “non-epistemic reading” of OC, “hinges” are, strictly speaking, unknowable; still, this will not lead to skeptical conclusions.

This reading of OC was firstly proposed by Strawson (1985; for similar proposals, see also Wolgast 1987, Conway 1989). According to Strawson, for Wittgenstein skeptical doubts are neither meaningless nor irrational but simply unnatural. This is because, since the radical skeptical doubts are raised with respect to propositions that we find it natural to take for granted (such as “There are external objects” or “Human beings have bodies”), given our upbringing within a community that collectively holds them fast, we cannot help accepting Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” while lacking reasons and grounds in their favor. Thus, following this interpretation of OC, skeptical hypotheses should not rebutted by argument, but simply recognized as idle and unreal as they call into doubt what we cannot help believing, given our shared “form of life.”

A similar account has been proposed by Stroll (1994). According to Stroll, “hinges” lie at the foundation of our language-games with ordinary empirical propositions; as such, they cannot be said to be propositions in the ordinary sense, as they are not subject to truth and falsity or to verification and control.

Thus, the certainty of “hinges” such as “There are external objects” or “Human beings have bodies” has a non-propositional, pragmatic, or even animal nature that are not be subject to any epistemic evaluation.

This reflection on the “animal,” pre-rational certainty of “hinges” is the starting point of another “non-epistemic reading” of OC, proposed by Moyal-Sharrock (2004, 2005). As per Moyal-Sharrock, our confidence in Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” such as “There are material objects” or “Human beings have bodies” is not a theoretical or presuppositional certainty but a practical certainty that can express itself only as a way of acting (OC 7, 395); for instance, a “hinge” such as “Human beings have bodies” is the disposition of a living creature, which manifests itself in her acting in the certainty of having a body (Moyal-Sharrock, 2004, 67), and manifests itself in her acting embodied (walking, eating, not attempting to walk through walls, and so forth).

Accordingly, Cartesian skeptical arguments, even if prima facie compelling, rest on a misleading assumption: the skeptic is simply treating “hinges” as empirical, propositional knowledge-claims, while on the contrary, they express a pre-theoretical animal certainty, which is not subject to epistemic evaluation of any sort.

Due to this categorical mistake, a proponent of Cartesian skepticism conflates physical and logical possibility (2004, 170). That is to say, skeptical scenarios such as the BIV one are logically possible but just in the sense that they are conceivable; in other words, we can imagine skeptical scenarios, then run our skeptical arguments, and thus conclude that our knowledge is impossible. Still, the mere hypothesis that we might be disembodied BIV has no strength against the objective, animal certainty of “hinges” such as “There are material objects” or “Human beings have bodies,” just as merely thinking that “human beings can fly unaided” has no strength against the fact that human beings cannot fly without help.

Therefore, skeptical beliefs such as “I might be a disembodied BIV” or “I might be the victim of an Evil Deceiver” are nothing but belief-behavior (2004, 176), as the skeptic is doubting objectively certain “hinges”; thus, we should simply dismiss skeptical worries, for a skeptical scenario such as the BIV one does not and cannot have any consequences whatsoever on our epistemic practices or, more generally, on our “human form of life.”

This reading of OC has attracted several criticisms (see, for instance, Salvatore 2013, 2016). If, from one side, Moyal-Sharrock stresses the conceptual, logical indubitability of Moore’s “truisms,” she nonetheless seems to grant that the certainty of “hinges” stems from their function in a given context, to the extent that they can be sensibly questioned and doubted in fictional scenarios where they can “play the role” of empirical propositions. But crucially, if “hinges” are “objectively certainties” because of their role in our ordinary life, a skeptic can still argue that in the context of philosophical inquiry, Moore’s “commonsense certainties” play a role which, similar to the role they play in fictional scenarios, is both at odds with our “human form of life” and still meaningful and legitimate.

Moreover, despite Moyal-Sharrock’s insistence on the conceptual, logical indubitability of Moore’s “truisms of the commonsense,” her rendering of Wittgenstein’s strategy seems to resemble Williams’ proposal, thus incurring the objections we have already encountered against this reading. As it is argued throughout this work, to simply state that Cartesian skepticism has no consequence on our “human form of life” sounds like too much of a pragmatist response against the skeptical challenge. This is so because a skeptic can well agree that skeptical hypotheses have no consequence on our everyday practices or that they are just fictional scenarios; also, she can surely grant that Cartesian-style arguments cannot undermine the pre-rational confidence with which we ordinarily take for granted Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense.” But crucially, and as Wittgenstein was well aware, a skeptic can always argue that she is not concerned with practical doubt (OC 19) but with a, so to speak, purely philosophical one.

Also and more importantly, even if we agree with Moyal-Sharrock on the “nonsensical” nature of skeptical doubts, this nonetheless has no strength against Cartesian-style skepticism. Recall the feature of Cartesian skeptical arguments: take a skeptical hypothesis SH such as the BIV one and M, a mundane proposition such as “This is a hand.” Now, given the Closure principle, the argument goes as follows:

(S1) I do not know not-SH

(S2) If I do not know not-SH, then I do not know M

Therefore

(SC) I do not know M

In this argument, whether an agent is seriously doubting if she has a body or not is completely irrelevant to the skeptical conclusion, “I do not know M.” Also, a proponent of Cartesian-style skepticism can surely grant that we are not BIV, or that we are not constantly deceived by an Evil Genius and so on. Still, the main issue is that we cannot know whether we are victim of a skeptical scenario or not; thus, given Closure, we are still unable to know anything at all.

6. The Non-propositional Reading

Wittgenstein’s reflections on the structure of reason have influenced a more recent “Wittgenstein-inspired” anti-skeptical position, namely Pritchard’s “hinge-commitment” strategy (2016b), for which “hinges” are not beliefs but rather arational, non-propositional commitments, not subject to epistemic evaluation.

To understand his proposal, recall the following remarks we have already quoted supra:

If you are not certain of any fact, you cannot be certain of the meaning of your words either […] If you tried to doubt everything you would not get as far as doubting anything. The game of doubting itself presupposes certainty (OC 114–115).

The question that we raise and our doubts depend on the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were the hinges on which those turn [….] that is to say, it belongs to the logic of our scientific investigations that certain things are indeed not doubted […] If I want the door to turn, the hinges must stay put (OC 341–343).

As per Pritchard, here Wittgenstein would claim that the same logic of our ways of inquiry presupposes that some propositions are excluded from doubt; and this is not irrational or based on a sort of blind faith but, rather, belongs to the way rational inquiries are put forward (see OC 342) . As a door needs hinges in order to turn, any rational evaluation would then require a prior commitment to an unquestionable proposition/set of “hinges” in order to be possible at all.

A consequence of this thought (2016b, 3) is that any form of universal doubt such as the Cartesian skeptical one is constitutively impossible; there is simply no way to pursue an inquiry in which nothing is taken for granted. In other words, the same generality of the Cartesian skeptical challenge is then based on a misleading way of representing the essentially local nature of our enquiries.

This maneuver helps Pritchard to overcome one of the main problems facing Williams’ “Wittgensteinian Contextualism.” Recall that, following Williams, the Cartesian skeptical challenge is both legitimate and unsolvable, even if only in the more demanding philosophical context. On the contrary, argues Pritchard, as per Wittgenstein, there is simply nothing like the kind of universal doubt employed by the Cartesian skeptic, both in the philosophical and in the, so to say, non-philosophical context of our everyday epistemic practices. A proponent of Cartesian skepticism looks for a universal, general evaluation of our beliefs; but crucially, there is no such thing as a general evaluation of our beliefs, whether positive (anti-skeptical) or negative (skeptical), for all rational evaluation can take place only in the context of “hinges” which are themselves immune to rational evaluation.

Each and every one of our epistemic practices rests on “hinges” that we accept with certainty, a certainty which is the expression of what Pritchard calls “‘über-hinge’ commitment.” This would be an arational commitment toward our most basic beliefs (such as that “There are external objects” or “Human beings have bodies”) that, as we mentioned above, is not itself opened to rational evaluation, but that importantly is not a belief.

To understand this point, just recall Pritchard’s criticism toward Wright’s rational entitlement. As we have seen, Wright argues that it would be entirely rational to claim that we know Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” whenever we are involved in an epistemic practice which is valuable to us; but, Pritchard argues, in order to know a proposition, we need reasons to believe that proposition to be true. And as, following Wright, we have no reason to consider “hinges” true other than the fact that we need to take them for granted, then we cannot have knowledge of them either.

With these considerations in mind, we can come back to Pritchard’s “‘über-hinge’ commitment.” As we have seen, this commitment would express a fundamental arational relationship toward our most basic certainties, a commitment without which no knowledge is possible. Crucially, our basic certainties are not subject to rational evaluation; for instance, they cannot be confirmed or disconfirmed by evidence and thus they would be non-propositional in character (that is to say, they can be neither true nor false). Accordingly, they are not beliefs at all; rather, they are the expression of arational, non-propositional commitments. Thus, the skeptic is somewhat right in saying that we do not know Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense”; but this will not lead to skeptical conclusions, for our “hinge commitments” are not beliefs so they cannot be objects of knowledge. Therefore, the skeptical challenge is misguided in the first place.

Pritchard’s account is concerned first and foremost with the psychology of our inquiries, and not with the epistemic status of the “hinges”; thus, his reflections on the structure of reason are just meant to stress the local nature of our epistemic practices, for which we have to rule out general doubts such as the skeptical one. But (Salvatore, 2016) even if, following his strategy, we are able to retain our knowledge of “mundane” propositions, the skeptic will still be able to undermine our confidence in the rationality of our ways of inquiry; under skeptical scrutiny, we will be forced to admit that all our practices rest on unsupported, ungrounded arational presuppositions that are not, and crucially cannot be, rationally grounded.

7. The Framework Reading

Another reading of OC is the “framework reading” (McGinn, 1989; see also Coliva, 2010) according to which “hinges” are “judgments of the frame,” that is, conditions of possibility of any meaningful epistemic practice.

This reading stems from the passages in which Wittgenstein highlights the analogy between Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” and basic mathematical truths:

But why am I so certain that this is my hand? Doesn’t the whole language-game rest on this kind of certainty? Or: isn’t this “certainty” (already) presupposed in the language-game? […] Compare with this 12×12=144. Here too we don’t say “perhaps”. For, in so far as this proposition rests on our not miscounting or miscalculating and on our senses not deceiving us as we calculate, both propositions, the arithmetical one and the physical one, are on the same level. I want to say: The physical game is just as certain as the arithmetical. But this can be misunderstood. My remark is a logical and not a psychological one (OC 446– 447).

I want to say: If one doesn’t marvel at the fact that the propositions of arithmetic (e.g. the multiplication tables) are “absolutely certain”, then why should one be astonished that the proposition “This is my hand” is so equally? (OC 448).

According to McGinn, we should read Wittgenstein’s remarks on “hinges” in light of his views about mathematical and logical truths. In the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (henceforth TLP), Wittgenstein held what we might call an “objectivist” account of logical and mathematical truths, for which they were a description of the a priori necessary structure of reality. In the later phase of his thinking, Wittgenstein completely dismissed this view, suggesting instead that we should think of logical and mathematical truths as constituting a system of techniques originating and developed in the course of the practical life of human beings. What is important in these practices is not their truth or falsity but their technique-constituting role; so, the question about their truth or falsity simply cannot arise. Quoting Wittgenstein:

The steps which are not brought into question are logical inferences. But the reason is not that they “certainly correspond to the truth-or sort-no, it is just this that is called “Thinking”, “speaking”, “inferring”, “arguing”. There is not any question at all here of some correspondence between what is said and reality; rather is logic antecedent to any such correspondence; in the same sense, that is, as that in which the establishment of a method of measurement is antecedent to the correctness or incorrectness of a statement of length (RFM, I, 156).

That is to say, logical and mathematical truths define what “to infer” and “to calculate” is; accordingly, given their “technique-constituting” role, these propositions cannot be tested or doubted, for to accept and apply them is a constitutive part of our techniques of inferring and calculating.

If logical and mathematical propositions cannot be doubted, this is also the case for Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense.” Even if they resemble empirical, contingent knowledge claims, all these “commonsense certainties” play a peculiar role in our system of beliefs; namely, they are what McGinn calls “judgment of the frame” (1989, 139).

As mathematical and logical propositions define and constitute our techniques of inferring and calculating, “hinges” such as “This is a hand,” “The world existed long before my birth,” and “I am a human being” would then define and constitute our techniques of empirical description. That is to say, Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” would show us how to use words: what “a hand” is, what “the world” is, what “a human being” is and so on (1989, 142).

Both Moore and the skeptic misleadingly treat “hinges” such as “Human beings have bodies” or “There are external objects” as empirical propositions, which can be known or believed on the basis of evidence. But Moore’s “obvious truisms” are certain, their certainty being a criterion of linguistic mastery; in order to be considered a full participant of our epistemic practices, an agent must take Moore’s “obvious truism” for granted.

Even though the “framework reading” has generally been considered a more viable interpretation of Wittgenstein’s thought (see Coliva, 2010), its anti-skeptical strength has been the focus of some serious analysis. First, following this account, to take “hinges” for granted is a condition of possibility of our epistemic practices (1989, 116-120); still (Minar, 2005, 258), a skeptic can nonetheless argue that the indubitability of Moore’s “obvious truisms of the commonsense” is nothing but a fact about what we do. That is to say, “hinges” such as “Human beings have bodies” or “There are external objects” are presupposed by our ordinary linguistic exchanges and constitute what McGinn calls our “framework judgments”; but once these “obvious truisms” are brought into focus, the skeptic will find that their not being up for questioning is simply what happens in normal circumstances. As we have already seen while presenting Conant’s and Wright’s readings of OC, the very fact that in our ordinary life we have to rule out skeptical hypotheses has no strength against Cartesian skepticism; again, what is at issue in the skeptical challenge is not the practical, but the epistemic rationality of setting aside skeptical concerns when we cannot rule out Cartesian-style scenarios.

8. Concluding Remarks

Given the elusive nature of Wittgenstein’s remarks on skepticism, there is still little to no consensus on how they should be interpreted or, more generally, whether Wittgenstein’s remarks alone can represent a valid response to radical skepticism. Pritchard’s (2016b, c) reflection on “hinges,” for example, are just one part of a more complex anti-skeptical framework that he calls epistemological disjunctivism (Pritchard, 2016b) and that would be impossible to summarize here. Coliva (2010, 2015) has recently proposed a version of the “framework reading” in which “hinges,” even if propositional, have a normative role, and their acceptance is a “condition of possibility” of any rational enquiry (on Coliva’s reading of OC and its anti-skeptical implications, see Moyal-Sharrock, 2013, and Pritchard & Boult, 2013). On the contrary, Salvatore (2015, 2016) has used the analogy drawn by Wittgenstein between “hinges” and “rules of grammar” in order to argue for the nonsensicality of skeptical hypotheses, which would be nonsensical combination of signs excluded by our epistemic practices (defined and constituted by “hinges” such as “Human beings have bodies” or “There are external objects”).

9. References and Further Reading

- Clarke, T. (1972), “The Legacy of Skepticism,” The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 69, No. 20, Sixty-Ninth Annual Meeting of the American Philosophical Association Eastern Division, 754–769.

- Conway, G. D. (1989), Wittgenstein on Foundations, Atlantic Highlands, N.J., Humanities Press.

- Coliva, A. (2015), Extended Rationality: A Hinge Epistemology, Palgrave MacMillan.

- Coliva, A. (2010), Moore and Wittgenstein. Scepticism, Certainty and Common Sense, Palgrave MacMillan.

- Coliva, A. (2009a), “Moore’s Proof and Martin Davies’ epistemic projects,” Australasian Journal of Philosophy.

- Coliva, A. (2009b), “Moore’s Proof, Liberals and Conservatives. Is There a Third Way?” in A. Coliva (ed.) Mind, Meaning and Knowledge. Themes from the Philosophy of Crispin Wright, OUP.

- Conant, J. (1998), “Wittgenstein on Meaning and Use,” Philosophical Investigations.

- Malcolm, N. (1949), “Defending Common Sense,” Philosophical Review.

- Minar, E. (2005), “On Wittgenstein’s Response to Scepticism: The Opening of On Certainty,” in D. Moyal-Sharrock and W.H. Brenner (eds.), Readings of Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, London, Palgrave, 253–274.

- Moore, G. E. (1925), “A Defense of Common Sense,” in Contemporary British Philosophers, 1925, reprinted in G. E. Moore, Philosophical Papers, London, Collier Books, 1962.

- Moore, G. E. (1939), “Proof of an External World,” Proceedings of the British Academy, reprinted in Philosophical Papers.

- Moore, G. E. (1942), “A Reply to My Critics,” in Paul Arthur Schilpp (ed.), The Philosophy of G. E. Moore. Open Court.

- Moyal-Sharrock, D. (2013), “On Coliva’s Judgmental Hinges,” Philosophia, Vol. 41, No. 1, 13–25.

- Moyal-Sharrock, D. (2004), Understanding Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, London, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moyal-Sharrock, D. and Brenner, W. H. (2005), Readings of Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, London, Palgrave.

- McGinn, M. (1989), Sense and Certainty: A Dissolution of Scepticism, Oxford, Blackwell.

- Morawetz, T. (1978), Wittgenstein & Knowledge: The Importance of “On Certainty,” Cambridge, MA, Harvester Press.

- Pritchard, D. H. (2016a), Epistemic Angst. Radical Scepticism and the Groundlessness of Our Believing, Princeton University Press.

- Pritchard, D. H. (2016b), “Wittgenstein on Hinges and Radical Scepticism in On Certainty,” Blackwell Companion to Wittgenstein, H.-J. Glock & J. Hyman (eds.), Blackwell.

- Pritchard, D. H. and Boult, C. (2013), “Wittgensteinian anti-scepticism and epistemic vertigo,” Philosophia, Vol. 41, No. 1, 27–35.

- Pritchard, D. H. (2005), “Wittgenstein’s On Certainty and Contemporary Anti-skepticism,” in Readings of Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, D. Moyal-Sharrock and W.H. Brenner (eds.), London, Palgrave, 189–224.

- Salvatore, N. C. (2016), “Skepticism and Nonsense,” Southwest Philosophical Studies.

- Salvatore, N. C. (2015), “Wittgensteinian Epistemology and Cartesian Skepticism,” Kriterion-Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 29, No. 2, 53–80.

- Salvatore, N. C. (2013), “Skepticism, Rules and Grammar,” Polish Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 7, No. 1, 31–53.

- Strawson, P. F. (1985), Skepticism and Naturalism: Some Varieties, London, Methuen.

- Stroll, A. (1994), Moore and Wittgenstein On Certainty, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Stroud, B. (1984), The Significance of Philosophical Scepticism, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Williamson, T. (2000), Knowledge and Its Limits, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Williams, M. (2004a), “Wittgenstein’s Refutation of Idealism,” in Wittgenstein and Skepticism, D. McManus (ed.), London, New York, Routledge, 76–96.

- Williams, M. (2004b), “Wittgenstein, Truth and Certainty,” in Wittgenstein’s Lasting Significance, M. Kolbel, B. Weiss (eds.), Routledge, London.

- Williams, M. (2005), “Why Wittgenstein isn’t a Foundationalist,” in Readings of Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, D. Moyal-Sharrock and W. H. Brenner (eds.), 47–58.

- Wright, C. (1985), “Facts and Certainty,” Proceedings of the British Academy, Vol. 71, 429–472.

- Wittgenstein, L. (2009), Philosophical Investigations, revised 4th edn. edited by P. M. S. Hacker and Joachim Schulte, tr. G. E. M. Anscombe, P. M. S. Hacker and Joachim Schulte, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1979), Wittgenstein’s Lectures, Cambridge 1932–35, from the Notes of Alice Ambrose and Margaret MacDonald, ed. Alice Ambrose, Blackwell, Oxford.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1974) Philosophical Grammar, ed. R. Rhees, tr. A. J. P. Kenny, Blackwell, Oxford.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1969), On Certainty, ed. G. E. M. Anscombe and G. H. von Wright, tr. D. Paul and G. E. M. Anscombe, Blackwell, Oxford.

- Wolgast, E. (1987), “Whether Certainty is a Form of Life,” The Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 37, 161–165.

- Wright, C. (2004a), “Warrant for nothing (and foundation for free)?” Aristotelian society Supplement, Vol. 78, No. 1, 167–212.

- Wright, C. (2004b), “Wittgensteinian Certainties,” in Wittgenstein and Skepticism, D. McManus (ed.), 22–55.

Author Information

Nicola Claudio Salvatore

Email: n162970@dac.unicamp.br

University of Campinas – UNICAMP

Brazil