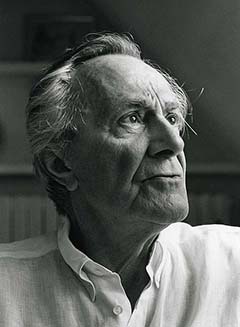

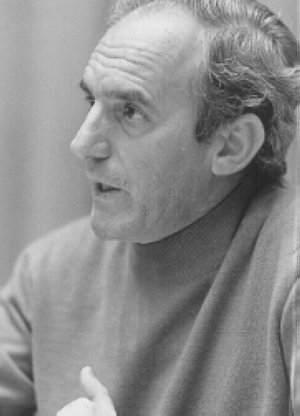

Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995)

Deleuze is a key figure in postmodern French philosophy. Considering himself an empiricist and a vitalist, his body of work, which rests upon concepts such as multiplicity, constructivism, difference, and desire, stands at a substantial remove from the main traditions of 20th century Continental thought. His thought locates him as an influential figure in present-day considerations of society, creativity and subjectivity. Notably, within his metaphysics he favored a Spinozian concept of a plane of immanence with everything a mode of one substance, and thus on the same level of existence. He argued, then, that there is no good and evil, but rather only relationships which are beneficial or harmful to the particular individuals. This ethics influences his approach to society and politics, especially as he was so politically active in struggles for rights and freedoms. Later in his career he wrote some of the more infamous texts of the period, in particular, Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus. These texts are collaborative works with the radical psychoanalyst Félix Guattari, and they exhibit Deleuze’s social and political commitment.

Deleuze is a key figure in postmodern French philosophy. Considering himself an empiricist and a vitalist, his body of work, which rests upon concepts such as multiplicity, constructivism, difference, and desire, stands at a substantial remove from the main traditions of 20th century Continental thought. His thought locates him as an influential figure in present-day considerations of society, creativity and subjectivity. Notably, within his metaphysics he favored a Spinozian concept of a plane of immanence with everything a mode of one substance, and thus on the same level of existence. He argued, then, that there is no good and evil, but rather only relationships which are beneficial or harmful to the particular individuals. This ethics influences his approach to society and politics, especially as he was so politically active in struggles for rights and freedoms. Later in his career he wrote some of the more infamous texts of the period, in particular, Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus. These texts are collaborative works with the radical psychoanalyst Félix Guattari, and they exhibit Deleuze’s social and political commitment.

Gilles Deleuze began his career with a number of idiosyncratic yet rigorous historical studies of figures outside of the Continental tradition in vogue at the time. His first book, Empirisism and Subjectivity, isa study of Hume, interpreted by Deleuze to be a radical subjectivist. Deleuze became known for writing about other philosophers with new insights and different readings, interested as he was in liberating philosophical history from the hegemony of one perspective. He wrote on Spinoza, Nietzche, Kant, Leibniz and others, including literary authors and works, cinema, and art. Deleuze claimed that he did not write “about” art, literature, or cinema, but, rather, undertook philosophical “encounters” that led him to new concepts. As a constructivist, he was adamant that philosophers are creators, and that each reading of philosophy, or each philosophical encounter, ought to inspire new concepts. Additionally, according to Deleuze and his concepts of difference, there is no identity, and in repetition, nothing is ever the same. Rather, there is only difference: copies are something new, everything is constantly changing, and reality is a becoming, not a being.

Table of Contents

- Biography

- The History Of Philosophy

- Two Examples: Kant and Leibniz

- A New Empiricism

- Hume

- Spinoza

- Nietzsche

- Deleuze’s Central Empiricist Concepts

- Difference And Repetition

- Difference-in-itself

- Contra-Hegel

- Repetition and Time

- The Image of Thought

- Capitalism And Schizophrenia – Deleuze And Guattari

- Literature, Cinema, Painting

- Literature

- Marcel Proust

- Leopold von Sacher-masoch

- Franz Kafka

- Cinema

- Painting

- What Is Philosophy?

- Early Reflections – Naturalism

- “What is Philosophy?” – Constructivism

- References and Further Reading

- Main texts

- Secondary texts

- Books and Collections of Essays

- Additional Uncollected Articles

1. Biography

Gilles Deleuze was born in the 17th arrondisment of Paris, a district that, excepting periods in his youth, he lived in for the whole of his life. He was the son of an conservative, anti-Semitic engineer, a veteran of World War I. Deleuze’s brother was arrested by Germans during the Nazi occupation of France for alleged resistance activities, and died on the way to Auschwitz.

Due to his families’ lack of money, Deleuze was schooled at a public school before the war. When the Germans invaded France, Deleuze was on vacation in Normandy and spent a year being schooled there. In Normandy, he was inspired by a teacher, under whose influence he read Gide, Baudelaire and others, becoming for the first time interested in his studies. In a late interview, he states that after this experience, he never had any trouble academically. After returning to Paris and finishing his high school education, Deleuze attended the Lycée Henri IV, where he did his kâgne, an intensive year of study for students of promise, in 1945, and then studied philosophy at the Sorbonne with figures such as Jean Hippolyte and Georges Canguilheim. He passed his agrégation in 1948, necessary for entry into the teaching profession, and taught in a number of high schools until 1956. In this year, he also married Denise Paul “Fanny” Grandjouan, a French translator of D.H. Lawrence. His first book, Empiricism and Subjectivity, on David Hume, was published in 1953, when he was 28.

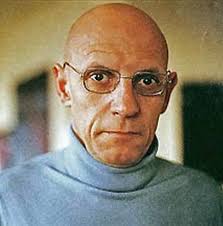

Over the next ten years, Deleuze held a number of assistant teaching positions in French universities, publishing his important text on Nietzsche (Nietzsche and Philosophy) in 1962. It was also around this time that he met Michel Foucault, with whom he had a long and important friendship. When Foucault died, Deleuze dedicated a book-length study to his work (Foucault 1986). In 1968, Deleuze’s doctoral thesis, comprising of Difference and Repetition and Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza were published. This was also the period of the first major incidence of pulmonary illness that would plague Deleuze for the rest of his life.

In 1969, Deleuze took up a teaching post at the ‘experimental’ University of Paris VII, where he taught until his retirement in 1987. In the same year, he met Félix Guattari, with whom he wrote a number of influential texts, notably the two volumes of Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Anti-Oedipus (1972) and A Thousand Plateaus (1980). These texts were considered by many (including Deleuze) to be an expression in part of the political ferment in France during May 1968. During the seventies, Deleuze was politically active in a number of causes, including membership in the Groupe d’information sur les prisons (formed, with others, by Michel Foucault), and had an engaged concern with homosexual rights and the Palestinian liberation movement.

In the eighties, Deleuze wrote a number of books on cinema (the influential studies The Movement-Image (1983) and The Time-Image (1985)) and on painting (Francis Bacon (1981)). Deleuze’s final collaboration with Guattari, What is Philosophy?, was published in 1991 (Guattari died in 1992).

Deleuze’s last book, a collection of essays on literature and related philosophical questions, Essays Critical and Clinical, was published in 1993. Deleuze’s pulmonary illness, by 1993, had confined him quite severely, even making it difficult for him to write. He took his own life on November 4th, 1995.

2. The History Of Philosophy

Deleuze’s whole intellectual trajectory can be traced by his shifting relationship to the history of philosophy. While in later years, he became quite critical of both the style of thought implied in narrow reproductions of past thinkers and the institutional pressures to think on this basis, Deleuze never lost any enthusiasm for writing books about other philosophers, if in a new way. Most of his publications contain the name of another philosopher as part of the title: Hume, Kant, Spinoza, Nietzsche, Bergson, Leibniz, Foucault.

Deleuze expresses two main problems with the traditional style and institutional location of the history of philosophy. The first concerns a politics of the tradition:

The history of philosophy has always been the agent of power in philosophy, and even in thought. It has played the repressors role: how can you think without having read Plato, Descartes, Kant and Heidegger, and so-and-so’s book about them? A formidable school of intimidation which manufactures specialists in thought – but which also makes those who stay outside conform all the more to this specialism which they despise. An image of thought called philosophy has been formed historically and it effectively stops people from thinking. (D 13)

This hegemony of thought recurrently comes under attack later in Deleuze’s career, notably in What is Philosophy? This criticism also sits well with a general theme throughout his writings, which is the immediate politicisation of all thought. Philosophy and its history is not separated from the fortunes of the wider world, for Deleuze, but intimately linked to it, and to the forces at work there.

The second criticism directed at the traditional style of history of philosophy, the construction of specialists and expertise, leads directly to the foremost positive aspect of Deleuze’s particular method: “What we should in fact do, is stop allowing philosophers to reflect ‘on’ things. The philosopher creates, he doesn’t reflect.” (N122) And this creation, with regard to other writers, takes the form of a portrait:

The history of philosophy isn’t a particularly reflective discipline. It’s rather like portraiture in painting. Producing mental, conceptual portraits. As in painting, you have to create a likeness, but in a different material: the likeness is something you have to produce, rather than a way of reproducing anything (which comes down to just repeating what a philosopher says). (N 136)

Perhaps such a method does not seem extremely creative, or perhaps only in a relatively passive sense. For Deleuze, however, the history of philosophy also embraces a much more active, constructive sense. Each reading of a philosopher, an artist, a writer should be undertaken, Deleuze tells us, in order to provide an impetus for creating new concepts that do not pre-exist (DR vii).

Thus the works that Deleuze studies are seen by him as inspirational, but also as a resource, from which the philosopher can gather the concepts that seem the most useful and give them a new life, along with the force to develop new, non-preexistent concepts.

In an important sense, Deleuze’s whole modus operandi is based in this revaluation of the role of other thinkers, and the means by which one can use them: each of his books either centers around one philosopher, or derives much of its texture from references to others. In any case, new concepts are derived from others’ works, or old ones are recreated or ‘awakened’, and put to a new service.

a. Two examples: Kant and Leibniz

Deleuze’s book on Kant, his third publication (1963) in general conforms with the standards of an academic philosophical study. Aside from its surprising breadth, covering as it does all three of Kant’s Critiques in a slender volume, it focuses on a problem that is clearly of concern to both Kant himself and the traditional reading of his work, that of the relationship between the faculties. Deleuze himself, later reflecting on Kant’s Critical Philosophy, distinguishes it from the other, more constructivist historical studies:

My book on Kant’s different; I like it, I did it as a book about an enemy that tries to show how his system works, its various cogs – the tribunal of Reason, the legitimate exercises of the faculties. (N 6)

There are, however, some distinctively creative elements even to this apparently sober study, which reflect Deleuze’s general interests, two in particular. In this text on Kant, these reveal themselves by way of emphasis, rather than out-and-out creation.

The first of these is his emphasis on Kant’s rejections of transcendentality at key points in the Critiques, in favour of a generalised pragmatism of reason. While Deleuze himself locates in Kant the development of the concept of the transcendental at the root of modern philosophy (DR 135), he is quick to insist that, even as transcendental faculties in Kant, understanding, reason and imagination act only in an immanent fashion to achieve their own ends:

. . . the so-called transcendental method is always the determination of an immanent employment of reason, conforming to one of its interests. The Critique of Pure Reason thus condemns the transcendent employment of a speculative reason which claims to legislate by itself; the Critique of Practical Reason condemns the transcendent employment of practical reason which, instead of legislating by itself, lets itself be empirically conditioned. (KCP 36-7; cf. KCP 24-5; NP 91)

Deleuze, then, insists on the critical activity of Kant’s philosophy as not only a critique of reason used wrongly, but specifies this critique in pragmatic and empiricist terms.

The second Deleuzian feature of Kant’s Critical Philosophy is its insistence on the creative and affirmative nature of the Critique of Judgement. This runs counter not just to a number of Kant scholars, who suggest that the third Critique is a defected work as a result of Kant’s age and decaying mental abilities when he wrote it, but also other prominent French philosophers of Deleuze’s generation, notably Jean-Francois Lyotard and Jacques Derrida, who both consider this text primarily in terms of its aporetic nature.

Deleuze, to the contrary, insists on its central importance to Kant’s philosophy. He argues not only that there are conflicts between the activity of the faculties, and thus between the first two Critiques, a moot point in reading Kant, but that the Critique of Judgement solves this problem (already a controversial perspective) by positing a genesis of free accord between the faculties deeper than their conflicts. Not only are the struggles between the faculties not insoluble: there is in fact an affirmative creation of a resolution that does not rely upon any transcendental faculty.

When we turn to consider a much later text, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, we find Deleuze’s constructivist practice of the history of philosophy developed to its fullest. This text is not only a “portrait” of Leibniz’s thought, but uses concepts drawn from it, along with new concepts based in a philosophical ‘take’ on mathematics, art, and music, to characterise the Baroque period, and indeed vice versa. Leibniz, Deleuze argues, is the philosopher whose point of view can be best used to understand the Baroque period, and Baroque architecture, music and art give us a unique and illuminating vantage point for reading Leibniz. In fact, one of the more astonishing claims that Deleuze makes is that the one cannot be understood properly without the other:

It is impossible to understand the Leibnizian monad, and its light-mirror-point of view-interior decoration system, if we do not come to terms with these elements in Baroque architecture. (FLB 39; translation altered)

How is such a statement to be demonstrated? Instead of claiming that in fact there is an a priori link between Leibniz and the Baroque, Deleuze creates a new concept, and reads both of them through it: this is the concept of the fold. In keeping with Leibniz’s theory of the monad, that the whole universe is contained within each being, like the Baroque church, Deleuze argues that the process of folding constitutes the basic unit of existence. While there are elements of the fold already in Leibniz and the architecture and art of the period, as Deleuze points out (N 157), it gains a new consistency and significance when used as a creative term in this manner. Throughout the book, and later, in Foucault, Deleuze uses the concept of the fold to describe the nature of the human subject as the outside folded in: an immanently political, social, embedded subject.

In addition, in The Fold, we see a remarkable cross-section of Deleuze’s whole work, expressed in a new way through the material that he analyses. Chapters 4 and 6 give a succinct formulation of the relationship between the event and the subject (one of Deleuze’s perennial interests), which leads to a new formulation of the nature of sufficient reason in line with Deleuze’s concept of the virtual. We also see a return to the question of the body that he examines with Guattari in Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (FLB sec III: ‘Having a body’), which reinstates the work of Leibniz on the level of the material, rather than in the realm of idealism.

Deleuze thus provides a reading of Leibniz that strikes the reader as eccentric and certainly at odds with the traditional approach, and yet which holds to both the text (in all his historical studies, Deleuze cites quite exhaustively), and to the new direction that he is working in.

3. A New Empiricism

In the English preface to the Dialogues, Deleuze writes the following:

I have always felt that I am an empiricist . . . [My empiricism] is derived from the two characteristics by which Whitehead defined empiricism: the abstract does not explain, but must itself be explained; and the aim is not to rediscover the eternal or the universal, but to find the conditions under which something new is produced (creativeness). (D vii; cf. N 88; WP 7)

One can see that such a definition of empiricism differs sharply, at least apparently, from the traditional understanding canonised by Anglo-American histories of philosophy. Such a history would have us believe that empiricism is above all the doctrine that whatever knowledge that we possess is derived from the senses and the senses alone – the well-known rejection of innate ideas. Modern views of science embrace such a doctrine, and apply it as a tool to derive facts about the physical world.

Deleuze’s empiricism is both an extreme radicalisation and rejection of this sense-data model: “Empiricism is by no means . . . a simple appeal to lived experience.” (DR xx; cf. PI 35). Rather, it takes a standpoint regarding the transcendental in general. Writing of Hume, he states that, We can now see the special ground of empiricism: . . . nothing is ever transcendental.” (ES 24) To claim that knowledge is derived from the senses alone and not from ideas which exist in the mind prior to experience (as is argued in a long tradition from Plato to Descartes and beyond, lingering in the discourse of modern science) is indeed a rejection of a certain transcendentality of the mind, but for Deleuze, this is only the very first moment of a radical displacement of all transcendentals that is central in all of his work: questioning the supremacy of reason as the a priori privileged way of relating to the world, questioning the link between freedom and will, attempting to abolish dualisms from ontology, reinstating politics prior to Being.

To return to the citation from the Dialogues, there are two aspects of Deleuze’s empiricist philosophy. The first is the rejection of all transcendentals, but the second is an active element: for Deleuze, empiricism is always about creating. In terms of philosophy, the creation par excellence is the creation of concepts: “Empiricism is by no means a reaction against concepts . . . On the contrary, it undertakes the most insane creation of concepts ever.” (DR xx) This idea of philosophy as an empiricist creation of concepts, or constructivism, is taken up again in What is Philosophy?, and is present, as noted above, in all of his historical studies of philosophers.

These two facets of empiricism are throughout Deleuze’s work, and it is in this sense that his claim about being such a philosopher is clearly true. Deleuze primarily developed this point of view through the texts he wrote prior to 1968, and particularly through three other philosophers, who he reads as empiricists in the sense mentioned: Hume, Spinoza and Nietzsche.

a. Hume

Deleuze’s first publication, Empiricism and Subjectivity (1953) is a book about David Hume, who is generally considered the foremost and most rigorous British empiricist, according to the general ‘sense-data’ model described above. Deleuze, however, takes Hume to be far more radical than he is normally considered to be. While this text very carefully reads Hume’s works, especially the Treatise of Human Nature, the portrait that emerges is quite strikingly idiosyncratic.

On Deleuze’s account, Hume is above all a philosopher of subjectivity. His central concern is to establish the basis upon which the subject is formed. All the well-known arguments about habit, causation and miracles reveal a more profound question: if there is nothing transcendental, how are we to understand the self-aware, creative self who seems to govern the nature that he somehow has sprung up from? Deleuze argues then that the relation between human nature and nature is Hume’s central concern (ES 109).

Deleuze develops this argument by asserting precisely the opposite of the traditional reading of Hume:

According to Hume, and also Kant, the principles of knowledge are not derived from experience. But in the case of Hume, nothing is transcendental, because these principles are simply principles of our nature . . . (ES 111-2)

Kant proposed transcendental operations of categories in order to make experience possible, criticising Hume for thinking that we could have unified knowledge of an empirical flux that we only passively receive. On Deleuze’s reading, however, Hume did not suppose that there were no unifying processes at work, on the contrary. The difference is that for Hume, these principles are natural; they do not rely upon the postulation of a priori structures of experience.

The question of the subject is resolved by Hume, according to Deleuze, by the creation of a number of key concepts: association, belief, and the externality of relations. Association is the principle of nature which operates by establishing a relation between two things. The imagination is affected by this principle to create a new unity, which can in turn be used later on to come to conclusions about other ideas that this unity resembles, is closely related to, or seems to cause. If we consider the traditional example of the balls on a pool table, the process of association allows a subject to form a relation of causality between one ball and the next, so that the next time one ball comes into contact with another, an expectation that the second ball will move is created.

Thus Hume, for Deleuze, considers the mind to be a system of associations alone, a network of tendencies (ES 25): “We are habits, nothing but habits – the habit of saying ‘I’. Perhaps there is no more striking answer to the problem of the Self.” (ES x.) The mind, affected by the natural principle of association, becomes human nature, from the ground up:

Empirical subjectivity is constituted in the mind under the influence of the principles affecting it; the mind therefore does not have the characteristics of a preexisting subject. (ES 29)

These associations account not only for experience in the basic sense, but up to the highest level of social and cultural life: this is the basis for Hume’s rejection of a social contract model of society (such as Hobbes’), in favour of convention alone. Morals, feelings, bodily comportment, all of these elements of subjectivity are explained, not by transcendental structures, such as Kant will propose, but the immanent activity of association.

Once this habitual structure of the self is in place, Deleuze suggests, the Humean concept of belief comes into play, which is resolutely a central part of human nature. It describes the particularly human way of going beyond the given. When we expect the sun to come up tomorrow, we do not do so because we know that it will, but because of a belief based on a habit. This in turn reverses the hierarchy of knowledge and belief, and results, for Deleuze, in a, “great conversion of theory to practice.” (PI 36) Every act of belief is a practical application of habit, without any reference to an a priori ability to judge. Not only is the human being thus habitual, on Deleuze’s reading, but also creative, even in the most mundane moments of life.

Finally, Deleuze insists that one of Hume’s greatest contributions to modern philosophy is his insistence that all relations are external to their terms: this is the essence of Hume’s anti-transcendental stance. Human nature cannot unite itself, there is no ‘I’ which stands before experience, but only moments of experience themselves, unattached and meaningless without any necessary relation to each other. A flash of red, a movement, a gust of wind, these elements must be externally related to each other to create the sensation of a tree in autumn. In the social world, this externality attests to the always-already interested nature of life: no relation is necessary, or governed by neutral laws, so every relation has a localised and passional motive. The ways in which habits are formed attests to the desires at the heart of our social milieu.

Subjectivity, as Deleuze describes it through his reading of Hume, is a practical, passional, empiricist concept, immediately located at the heart of the conventional, which is to say the social.

b. Spinoza

While Hume may not be a contentious name to link with a deepened empiricism, Benedict de Spinoza certainly is. Generally considered the arch-rationalist par excellence, Spinoza is most well known for the first main thesis proposed in his Ethics: that there is one substance, God or Nature, and that everything that exists is merely a modulation of this substance. His style of writing, known as the ‘geometric method’, is composed by propositions, proofs, and axioms. Such a point of view hardly seems consistent with a radical construction of concepts, and an essential pragmatism: and yet this is what Deleuze’s interpretation of Spinoza, which has been very influential (as recent texts such as those by Geneveive Lloyd and Moira Gatens demonstrate), argues.

Spinoza is without a doubt the philosopher most praised and referred to by Deleuze, often with words that are rarely a part of philosophical writing. For example:

Spinoza is, for me, the ‘prince’ of philosophers. (EPS 11)

Spinoza is the Christ of philosophers, and the greatest philosophers are hardly more than apostles who distance themselves from or draw near to this mystery. (WP 60)

Spinoza: the absolute philosopher, whose Ethics is the foremost book on concepts. (N 140)

Spinoza’s greatness for Deleuze comes precisely from his development of a philosophy based on the two features of empiricism discussed above. Indeed, for Deleuze, Spinoza combines the two things into one movement: a rejection of the transcendental in the action of creating a plane of absolute immanence upon which all that exists situate themselves. In more Spinozist language, we can refer to the thesis of a single substance instead of a plane of immanence; all bodies (beings) are modal expressions of the one substance (SPP 122).

But not only is The Ethics for Deleuze the creation of a plane of immanence, it is the creation of a whole regime of new concepts that revolve around the rejection of the transcendental in all spheres of life. The unity of the ontological and the ethical is crucial, for Deleuze, in understanding Spinoza, that is:

Spinoza didn’t entitle his book Ontology, he’s too shrewd for that, he entitles it Ethics. Which is a way of saying that, whatever the importance of my speculative propositions may be, you can only judge them at the level of the ethics that they envelope or imply [impliquer].

In short, as the title of one of Deleuze’s books, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, indicates, the Ethics is only understood when it is seen, at one and the same time, to be theoretical and practical. Deleuze considers there to be three primary theoretico-practical points in the Ethics:

The great theories of the Ethics . . . cannot be treated apart from the three practical theses concerning consciousness, values and the sad passions (SPP 28)

First of all, the illusion of consciousness. Spinoza argues that we are not the cause of our thoughts and actions, but only assume that we are based on their affects upon us. This leads to dualisms of substance (such as Descartes’ mind/body split). Deleuze insists on this point because he sees Spinoza bypassing an important illusion of subjectivity: we suppose that we are causes and not effects.

The illusion of consciousness, for Spinoza a result of inadequate knowledge and sad affects, allows us to posit a transcendental consciousness supposedly free from the interventions of the world (as in Descartes). This is in fact a blind-spot which precludes us from knowing ourselves as caused, the practical meaning of which is that we deny our own ‘sociality’, as one mode amongst others, and the significance of the relations that we enter into, which actually determine our power to act, and our ability to experience active joy.

The second is the critique of morality. Spinoza’s Ethics, for Deleuze, constitutes a rejection of the transcendent Good/Evil distinction in favour of a merely functional opposition between good and bad. Good and Evil, for Spinoza as for Lucretius and Nietzsche, are the illusions of a moralistic world-view that does nothing but reduce our power to act and encourages the experience of the sad passions (SPP 25; LS 275-8). The Ethics is for Deleuze rather an incitement to consider encounters between bodies on the basis of their relative ‘goodness’ for those modes that are relating. The shark enters into a good relation with salt water, which increases its power to act, but for fresh water fish, or for a rose bush, salt water only degrades the characteristic relations between the parts of the bush and threatens to destroy its existence.

So actions have no transcendental scale to be measured upon (the theological illusion), but only relative and perspectival good and bad assessments, based on specific bodies. Thus the Ethics is, for Deleuze, an ‘ethology’, that is, a guide to obtaining the best relations possible for bodies.

Finally, Deleuze sees in Spinoza the rejection of the sad passions. This point is linked to the last, and again closely related to Nietzsche’s critique of ressentiment and slave morality. Sad passions are for Spinoza all those forces which disparage life. For Deleuze, Spinoza,

denounces all the falsifications of life, all the values in the name of which we disparage life. We do not live, we only lead a semblance of life; we can only think of how to keep from dying, and our whole life is a death worship. (SPP 26)

The hinge that this practical reading of Spinoza turns on is Deleuze’s angle of approach to the Ethics. Rather than emphasising the great theoretical structures found in the first few sections, Deleuze emphasises the later part of the book (particularly part V), which consists in arguments from the point of view of individual modes. This approach puts the importance on the reality of individuals rather than form, and on the practical rather than the theoretical. In the preface to the English translation of Expressionism in Philosophy, he writes:

What interested me most in Spinoza wasn’t his Substance, but the composition of finite modes . . . That is: the hope of making substance turn on finite modes, or at least of seeing in substance a plane of immanence in which finite modes operate . . .” (EPS 11)

Deleuze’s reading of Spinoza has clear and profound relations with all that he wrote after 1968, especially the two volumes of Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

c. Nietzsche

Aside from Spinoza, Nietzsche is the most important philosopher for Deleuze. His name, and central concepts that he created appear almost without exception in all of Deleuze’s books. It would also be accurate to say that he reads both Spinoza and Nietzsche together, one through the other, and thus highlights the profound continuity of their thought.

The most significant work that Deleuze did with Nietzsche was his highly influential study Nietzsche and Philosophy, the first book in France to systematically defend and explicate Nietzsche’s work, still suspected of fascism, after the second World War. This text was and is extremely well regarded by other philosophers, including Jacques Derrida (Derrida 2001), and Pierre Klossowski, who wrote the other key French study on Nietzsche in the second half of last century (Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, which is dedicated to Deleuze).

While Nietzsche and Philosophy does deal with Nietzsche’s polemical targets, its originality and strength lies in its systematic exposition of the diagnostic elements of his thought. Indeed, one critique of this text is that it oversystematises a thinker and writer whose style of writing overtly resists such a summary approach. For Deleuze, however, it has been one of the hallmarks of bad readings of Nietzsche that they have relied upon a non-philosophical reading, either seeing him as a writer who attempts to assert other models of thought over philosopher, or, more commonly, as an obscurantist or (proto-) madman whose books have no coherence or value.

Nietzsche, for Deleuze, develops a symptomatology based on an analysis of forces that is elaborate, rigorous and systematic. He argues that Nietzsche’s ontology is monist, a monism of force: “There is no quantity of reality, all reality is already a quantity of force.” (NP 40) This force, in turn, is solely a force of affirmation, since it expresses only itself and itself to its fullest; that is, force says ‘yes’ to itself (NP 186). Deleuze’s reading of Nietzsche starts from this point, and accounts for the whole of Nietzsche’s critical typology of negation, sadness, reactive forces and ressentiment on this basis. The polemical basis of Nietzsche’s work, for Deleuze, is directed at all that would separate force from acting on its own basis, that is, from affirming itself.

There is not one force, but many, the play and interaction of which forms the basis of existence. Deleuze argues that the many antagonistic metaphors in Nietzsche’s writing should be interpreted in light of his pluralist ontology, and not as indications of some sort of psychological agressivity.

Nietzsche’s ontology, then, retains the suppleness and reliance on difference while remaining monist. Thus he, for Deleuze, is characterised as an anti-transcendental thinker.

Deleuze’s reading of Nietzsche demonstrates the extent to which he rejected the traditional, or dogmatic image of thought (see (4)(d) below), which relies upon a natural harmony between thinker, truth and the activity of thought. Thought does not naturally relate to truth at all, but is rather a creative act (NP xiv), an act of affect, of force on other forces: “As Nietzsche succeeded in making us understand, thought is creation, not will to truth.” (WP 54) There is no room for seeing truth as abstract generality (NP 103) in Deleuze’s account of Nietzsche, but rather to see truth itself as a part of regimes of force, as a matter of value, to be assessed and judged, rather than as an innate disposition (NP 108).

Once again, in Nietzsche, we are confronted with the problem of considering a philosopher who is generally considered to be quite foreign to the tradition of empiricist thought, as an empiricist. As with Spinoza, however, Deleuze’s reading of Nietzsche, as he himself indicates, relies upon his characterisation of empiricist thought: as the rejection of the transcendental, both in ontology and thought, and the consequent affirmation of thought as creativity.

d. Deleuze’s Central Empiricist Concepts

While Deleuze often refers to the central concepts of empiricism as classically formulated by Hume in the Treatise (association, habituation, convention etc.) (ES; LS 305-7; DR 70-3; WP 201-2), he also develops, throughout his work, a number of other key concepts which should be considered as empiricist. The most prominent of these are immanence, constructivism, and excess.

The key word throughout Deleuze’s writings, as we have seen, to be found in almost all of his main texts without fail, is immanence. This term refers to a philosophy based around the empirical real, the flux of existence which has no transcendental level or inherent seperation. His last text, published a few months before his death, bore the title, “Immanence: a life . . .” (PI 25-33). Deleuze repeatedly insists that philosophy can only be done well if it approaches the immanent conditions of that which it is trying to think; this is to say that all thought, in order to have any real force, must not work by setting up trancendentals, but by creating movement and consequences:

If you’re talking about establishing new forms of transcendence, new universals, restoring a reflective subject as the bearer of rights, or setting up a communicative intersubjectivity, then it’s not much of a philosophical advance. People want to produce ‘consensus’, but consensus is an ideal that guides opinion, and has nothing to do with philosophy. (N 152; cf. 145; WP chapter 2)

Deleuze’s insistence on the concept of the immanent also has an ontological sense, as we have seen in his studies of Spinoza and Nietzsche, and which returns later in works such as Difference and Repetition and Capitalism and Schizophrenia: there is only one substance, and therefore everything which exists must be considered on the same plane, the same level, and analysed by way of their relations, rather than by their essence.

Constructivism is the title that Deleuze uses to characterise the movement of thought in philosophy. This has two senses. Firstly, empiricism, immanent thought, must create movement, create concepts if it is to be philosophy and not just opinion or consensus. Deleuze and Guattari cite Nietzsche on this point: “[Philosophers] must no longer accept concepts as a gift, nor merely purify or polish them, but first make and create them, present them and make them convincing.” (WP 5)

Secondly, in relation to other philosophy, Deleuze maintains that we do not just repeat what they have already said (see (2) above): “Empiricism . . . [analyses] the states of things, in such a way that non-pre-existent concepts can be extracted from them.” (D vii) This constructivism, for Deleuze, holds weight in all areas of research, as he demonstrates in his studies of literature, cinema and art (see (6) below).

Constructivism, moreover, does not proceed along any predetermined lines. There is nothing that is necessary to create, for Deleuze: thought does not have a pre-given orientation (see (4)(b) below). Empiricist thought is thus always in some sense strategic (LS 17).

The concept of excess takes the place in Deleuze’s thought of the transcendent. Instead of an object, a table for example, being determined and given its essence by a transcendental concept or Idea (Plato) which is directly applicable to it, or the application of a transcendental category or schema (Kant), everything that exists is exceeded by the forces which constitute it. The table does not have a for-itself, but has existence within a field or territory, which are beyond its meaning or control. Thus a table exists in a kitchen, which is part of a three-bedroom family home, which is part of a capitalist society. In addition, the table is used to eat on, linking itself with the human body, and another produced, consumable item, a hamburger. For Deleuze, one can always analyse interminably in any direction these relations of force, which always move beyond the horizon of the object in question.

For Deleuze, however, nothing is exceeded more than subjectivity. This is not a statement of ontological priority, but bears on the extreme privilege the conscious-to-self subject has had in the history of Western thought, it is certainly here that Deleuze makes his most significant use of the concept of excess. Consider, for example: “Subjectivity is determined as an effect.” (ES 26). “There are no fewer things in the mind that exceed our consciousness than there are things in the body that exceed our knowledge.” (SPP 18)

The point is that human forces aren’t on their own enough to establish a dominant form in which man can install himself. Human forces (having an understanding, a will, an imagination and so on) have to combine with other forces: an overall form arises from this combination, but everything depends on the nature of other forces with which the human forces become linked. (N 117; cf. especially DR 254; 257-61)

While Deleuze protests that he never made a big deal out of rejecting traditional postulates like the subject (N 88), he frequently writes about the notion of the exceeded subject, from his first book on Hume and throughout his work. This in some sense locates him in the landscape of what is known as postmodern thought, along with other figures such as Jacques Derrida, Jean-Francois Lyotard and Michel Foucault.

4. Difference And Repetition

Difference and Repetition (1968) is without doubt Deleuze’s most significant book in a traditional academic style, and proposes the most central of his disruptions to the canonical traditions of philosophy. However, precisely for this reason, it is also one of his most difficult books, dealing as it does with two age-old, overdetermined philosophical topics, identity and time, and with the nature of thought itself.

a. Difference-in-itself

Deleuze’s main aim in Difference and Repetition is a creative elaboration of these two concepts, but it essentially precedes by way of a critique of Western philosophy. His central thesis is,

That identity not be first, that it exist as a principle but as a second principle, as a principle become; that it revolve around the Different: such would be the nature of a Copernican revolution which opens up the possibility of difference having its own concept, rather than being maintained under the domination of a concept in general already understood as identical. (DR 41)

From Plato (DR 59-63) to Heidegger (DR 64-6), Deleuze argues, difference has not been accepted on its own, but only after being understood with reference to self-identical objects, which makes difference a difference between. He attempts in this book to reverse this situation, and to understand difference-in-itself.

We can understand Deleuze’s argument by way of reference to his analysis of Plato’s three-tiered system of idea, copy and simulacrum (cf. LS 253-65). In order to define something such as courage, we can have reference in the end only to the Idea of Courage, an identical-to-itself, this idea containing nothing else (DR 127). Courageous acts and people can be thus judged by analogy with this Idea. There are also, however, those who only imitate courageous acts, people who use courage as a front for personal gain, for example. These acts are not copies of the courageous ideal, but rather fakes, distortions of the idea. They are not related to the Idea by way of analogy, but by changing the idea itself, making it slip. Plato frequently makes arguments based on this system, Deleuze tells us, from the Statesman (God-shepherd, King-shepherd, charlatan) to the Sophist (wisdom, philosopher, sophist) (DR 60-1; 126-8).

The philosophical tradition, beginning with Plato (although Deleuze detects some ambiguity here (eg. DR 59; TP 361)) and Aristotle, has sided with the model and the copy, and resolutely fought to exclude the simulacra from consideration, either by rejecting it as an external error (Descartes (DR 148)), or by assimilating it into a higher form, via the operation of a dialectic (Hegel (DR 263)).

While difference is subordinated to the model/copy scheme, it can only be a consideration between elements, which gives to difference a wholly negative determination, as a not-this. However, Deleuze suggests, if we turn our attention to the simulacra, the reign of the identical and of analogy is destabilised. The simulacra exists in and of itself, without grounding in or reference to a model: its existence is “unmediated” (DR 29), it is itself unmediated difference. It is for this reason that Deleuze makes his well-known claim that a true philosophy of difference must be “inverted-” or “anti-Platonism” (DR 127-8): the being of simulacra is the being of difference itself; each simulacra is its own model.

We might well ask here: what provides the unity of the different? How can we talk about the being of something that is difference itself? Deleuze’s answer is that precisely there is no intrinsic ontological unity. He takes up here Nietzsche’s idea that being is becoming: there is an internal self-differing within the different itself, the different differs from itself in each case. Everything that exists only becomes and never is.

Unity, Deleuze tells us, must be understood as a secondary operation (DR 41) under which difference is pressed into forms. The prominent philosophical notion he offers for such unity is time (see (4)(c) below), but later, in Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze and Guattari offer a political ontology that shows how this process of becoming is fixed into unitary formulations.

b. Contra-Hegel

Deleuze’s arch-enemy in Difference and Repetition is Hegel. While this critical stance is already clearly evident in Nietzsche and Philosophy and from there throughout his work, Deleuze’s revaluation of difference itself takes as its most essential form the rejection of the Hegelian dialectic, which represents the most extreme development of the logic of the identical.

The dialectic, Deleuze tells us, seems to operate with extreme differences alone, even so far as acknowledging them as the motor of history. Formed of two opposite terms, such as being and non-being, the dialectic operates by synthesising them into a new third term that preserves and overcomes the earlier opposition. Deleuze argues that this is a dead end which makes,

identity the sufficient condition for difference to exist and be thought. It is only in relation to the identical, as a function of the identical, that contradiction is the greatest difference. The intoxication and giddiness are feigned, the obscure is already clarified from the outset. Nothing shows this more than the insipid monocentrality of the circles in the Hegelian dialectic. (DR 263)

While offering a philosophical tool that sees difference at the heart of being, the process of the dialectic removes this affirmation as its most essential step.

The further consequence of this for Deleuze relates to the place of negation in Hegel’s system. The dialectic, in its general movement, takes specific differences, differences-in-themselves, and negates their individual being, on the way to a “superior” unity. Deleuze argues in Difference and Repetition that this step of Hegel’s mistakes ontology, history and ethics.

“Beneath the platitude of the negative lies the world of ‘disparateness'” (DR 267). There is no resolution of the differences-in-themselves into a higher unity that does not fundamentally misunderstand difference. Here Deleuze is clearly recalling his Spinozist and Nietzschean ontology of a single substance that is expressed in a multiplicity of ways (cf. DR 35-42; 269): In a famous sentence, he writes: “A single voice raises the clamour of being.” (DR 35)

Hegel is famous for asserting that the negating dialectic is the motor of history, proceeding towards the often-caricatured end of history and the realisation of absolute spirit. For Deleuze, history does not have a teleological element, a direction of realisation; this is only an illusion of consciousness (cf. SPP 17-22):

History progresses not by negation and the negation of negation, but by deciding problems and affirming differences. It is no less bloody and cruel as a result. Only the shadows of history live by negation . . . (DR 268)

Finally, regarding ethics, Deleuze argues that an ontology based on the negative makes of ethical affirmation a secondary, derived possibility: “The false genesis of affirmation . . .: if the truth be told, none of this would amount to much if it was not for the moral presuppositions and practical implications of such a distortion.” (DR 268)

c. Repetition and Time

For Deleuze, the central stake in the consideration of repetition is time. As with difference, repetition has been subjected to the law of the identical, but also to a prior model of time: to repeat a sentence means, traditionally, to say the same thing twice, at different moments. These different moments must be themselves equal and unbiased, as if time were a flat, featureless expanse. So repetition has essentially been considered as the traditional idea of difference over time understood in a common-sense way, as a succession of moments. Deleuze asks if, given a renovated understanding of difference as in-itself, we are able to reconsider repetition also. But there is also an imperative here, since, if we are to consider difference-in-itself over time, based in the traditional logic of repetition, we once again reach the point of identity. As such, Deleuze’s critique of identity must revaluate the question of time.

Deleuze’s argument proceeds through three models of time, and relates the concept of repetition to each of them.

The first is time as a circle. Circular time is mythical and seasonal time, the repetition of the same after time has passed through its cardinal points. These points may be simple natural repetitions, like the sun rising daily, the movement of summer to spring, or the elements of tragedy, which Deleuze suggests operate cyclically. There is a sense of both destiny and theology in the concept of time as a circle, as a succession of instants which are governed by an external law.

When time is considered in this fashion, Deleuze argues (DR 70-9), repetition is solely concerned with habit. The subject experiences the passing of moments cyclically (the sun will come up every morning), and contracts habits which make sense of time as a continually living present. Habit is thus the passive synthesis of moments that creates a subject.

The second model of time is linked by Deleuze to Kant (KCP vii-viii), and it constitutes one of the central ruptures that the Kantian philosophy creates in thought, for Deleuze: this is time as a straight line. In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant liberates time from the circular model by proposing it as a form that is imposed upon sensory experience. For Deleuze, this reverses the earlier situation by placing events into time (as a line), rather than seeing the chain of events constituting time by the passing of present moments.

Habit can thus no longer have any power, since in this model of time, nothing returns. In order for sense to be made of what has occurred, there must be an active process of synthesis, which makes of the past instances a meaning (DR 81). Deleuze calls this second synthesis memory. Unlike habit, memory does not relate to a present, but to a past which has never been present, since it synthesises from passing moments a form in-itself of things which never existed before the operation. The novels of Marcel Proust are for Deleuze the most profound development of memory as the pure past, or in Proust’s terminology, as time regained. (DR 122; PS passim)

In this second model of time, repetition thus has an active sense in line with the synthesis, since it repeats something, in the memory, that did not exist before – this does not save it, however, from being an operation of identity, nonetheless. These two moments, the active constitution of a pure past, and the disparate experience of a present yet to be synthesised produces a further consequence for Deleuze: as in Kant, a radical splitting of the subject into two elements, the I of memory, which is only a process of synthesis, and a self of experience, an ego which undergoes experience. (DR 85-7; KCP viii-ix)

Deleuze insists that both of these models of time press repetition into the service of the identical, and make it a secondary process with regards to time. The final model of time that Deleuze proposes attempts to make repetition itself the form of time.

In order to do this, Deleuze relates the concepts of difference and repetition to each other. If difference is the essence of that which exists, constituting beings as disparates, then neither of the first two models of time does justice to them, insisting as they do on the possibility and even necessity of synthesising differences into identities. It is only when beings are repeated as something other that their disparateness is revealed. Consequently, repetition cannot be understood as a repetition of the same, and becomes liberated from subjugation under the demands of traditional philosophy.

To give body to the conception of repetition as the pure form of time, Deleuze turns to the Nietzschean concept of the eternal return. This difficult concept is always given a forceful and careful qualification by Deleuze whenever he writes about it (eg. DR 6;41; 242; PI 88-9; NP 94-100): that it must not be considered as the movement of a cycle, as the return of the identical. As a form of time, the eternal return is not the circle of habit, even on the cosmic level. This would only allow the return of something that already existed, of the same, and would result again in the suppression of difference through an inadequate concept of repetition.

While habit returned the same in each instance, and memory dealt with the creation of identity in order to allow experience to be remembered, the eternal return is, for Deleuze, only the repetition of that which differs-from-itself, or, in Nietzsche’s terminology, only the repetition of those beings whose being is becoming: “The subject of the eternal return is not the same but the different, not the similar but the dissimilar, not the one but the many . . .” (DR 126)

As such, Deleuze tells us, repetition as the third meaning of time takes the form of the eternal return. Everything that exists as a unity will not return, only that which differs-from-itself. “Difference inhabits repetition.” (DR 76). So, while habit was the time of the present, and memory the being of the past, repetition as the eternal return is the time of the future.

The superiority of this third understanding of repetition as time has two main impetuses in Deleuze’s argument. The first is obviously that it keeps difference intact in its movement of differing-from-itself. The second is as significant, if for different reasons. If only what differs returns, then the eternal return operates selectively (DR 126; PI 88-9), and this selection is an affirmation of difference, rather than an activity of representation and unification based on the negative, as in Hegel.

d. The Image of Thought

Chapter three of Difference and Repetition provides a novel approach to an important question in philosophy, the problem of presuppositions. Deleuze pursues this topic again later in A Thousand Plateaus (374-80), and when he writes about conceptual personae in What is Philosophy? (ch. 3); he had already written on images of thought in Nietzsche and Philosophy (103-10) and Proust and Signs (94-102).

An example is Descartes’ celebrated phrase at the beginning of the Discourse on the Method:

Good sense is the most evenly shared thing in the world . . the capacity to judge correctly and to distinguish the true from the false, which is properly what one calls common sense or reason, is naturally equal in all men . .

For Descartes, thought has a natural orientation towards truth, just as for Plato, the intellect is naturally drawn towards reason and recollects the true nature of that which exists. This, for Deleuze, is an image of thought.

Although images of thought take the common form of an ‘Everybody knows . . .’ (DR 130), they are not essentially conscious. Rather, they operate on the level of the social and the unconscious, and function, “all the more effectively in silence.” (DR 167)

Deleuze undertakes a thorough analysis of the traditional philosophical image of thought, and lists eight features which, in all aspects of philosophical pursuit, imply a subordination of thought to externally imposed directives. He includes the good nature of thought, the priority of the model or recognition as the means of thought, the sovereignty of representation over supposed elements in nature and thought, and the subordination of culture to method (or learning to knowledge). These all imply an a priori nature of thought, a telos, a meaning and a logic of practice. These features,

crush thought under an image which is that of the Same and the Similar in representation, but profoundly betrays what it means to think and alienates the two powers of difference and repetition, of philosophical commencement and recommencement. (DR167)

It is this element, in Difference and Repetition, that founds Deleuze’s most serious criticism of the traditional image of thought: that it fails to come to terms with the true nature of difference and repetition. As a result, it is fair to say that this moment of the book is essential for understanding the way in which Deleuze both wants to base his assessment of traditional philosophies of identity and time, and how he wishes to exceed them: his reformulation of difference and repetition is made possible by this critique (cf. N 149).

The other critical angle Deleuze supplies here is related to the first, and derives from Nietzsche’s critique of Western thought:

When Nietzsche questions the most general presuppositions of philosophy, he says that these are essentially moral, since Morality alone is capable of convincing us that thought has a good nature and the thinker a good will, and that only the good can ground the supposed affinity between thought and the True. (DR132; cf. LS 3)

As we saw above regarding Hegel, the real point of concern is that this image of thought is in the service of practical, political and moral forces, it is not simply a matter of philosophy, in segregation from the rest of the world.

To the question ‘why do we have this image of thought?’ Deleuze, along with Nietzsche, that it is a moral image, and is in the service of power, but there is also a more intrinsic problem with thinking itself, that is only fully developed in the Conclusion to What is Philosophy?, and this is that thought itself is dangerous.

In contradistinction to the natural goodness of thought in the traditional image, Deleuze argues for thought as an encounter: “Something in the world forces us to think.” (DR 139) These encounters confront us with the impotence of thought itself (DR 147), and evoke the need of thought to create in order to cope with the violence and force of these encounters. The traditional image of thought has developed, just as Nietzsche argues about the development of morality in The Genealogy of Morals, as a reaction to the threat that these encounters offer. We can consider the traditional image of thought, then, precisely as a symptom of the repression of this violence.

As a result, the relationship of philosophy to thought must have two correlative aspects, Deleuze argues:

an attack on the traditional moral image of thought, but also a movement towards understanding thought as self-engendering, an act of creation, not just of what is thought, but of thought itself, within thought (DR 147).

This is true, dangerous thought, but the sole thought capable of approaching difference-in-itself and complex repetition: thought without an image. .

The thought which is born in thought, the act of thinking which is neither given by innateness nor presupposed by reminiscence but engendered in its genitality, is a thought without image. But what is such a thought, and how does it operate in the world? (DR 167; cf. 132)

This final question directs us towards the central aim of the two texts of Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

5. Capitalism And Schizophrenia – Deleuze And Guattari

The collaborative texts of Deleuze and Felix Guattari, particularly the two volumes of Capitalism and Schizophrenia, are outside of the scope of the current article (see the Deleuze and Guattari entry in this encyclopaedia, forthcoming). However, two brief points are important to note.

First, that despite the wide notoriety of these works as obscurantist and non-philosophical, they bear a profound relation to Deleuze’s philosophical enterprise in general, and develop in new ways many of his concerns: a commitment to an immanent ontology, the importance of the social and the political to the very heart of being, and the affirmation of difference over the transcendental hierarchy in every aspect of this work.

Secondly, the manner in which these texts are written by the two writers, between the two and not seperately, means that many new elements emerge that cannot be drawn from their work individually. As such, regarding Deleuze, many of the central ideas cited above do undergo an interesting and novel transformation into a new direction: the very type of relationship characterised in Capitalism and Schizophrenia as a becoming.

6. Literature, Cinema, Painting

Deleuze’s work on the arts, he never ceases to remind the reader, are not to be understood as literary criticism, film or art theory. Talking of the 1980’s, during which he wrote almost exclusively on the arts, he states the following:

let’s suppose that there’s a third period when I worked on painting and cinema: images on the face of it. But I was writing philosophy. (N 137)

This accords with the aims of Deleuze’s empiricism (see (3) above), to understand philosophy as an encounter (with a work, philosophical or artistic, an object, a person) out of which “non-pre-existent concepts,” (DR vii) can be created. Regarding his books on cinema, he is even more explicit:

Film criticism faces twin dangers: it shouldn’t just describe films but nor should it apply to them concepts taken from outside film. The job of criticism is to form concepts that aren’t of course ‘given’ in films but nonetheless relate specifically to cinema, and to some specific genre of film, to some specific film or other. Concepts specific to cinema, but which can only be formed philosophically. (N 58; C2 280)

All of Deleuze’s work on artists can be assembled under the rubric of the creation of new philosophical concepts that relate specifically to the work at hand, yet which also link these works with others more generally. Not a philosophy of the arts per se, but a philosophical encounter with specific artistic works and forms.

One feature that the artistic works also contain, distinct from many of Deleuze’s other books, is a concern with a taxonomy of signs. In Proust and Signs, Francis Bacon, and the Cinema books, Deleuze attempts to develop a systematic approach of classifying different signs. These signs are not linguistic (C1 ix), since they are not themselves elements of a system, but rather are types of emissions from a work. Proust, for example, on Deleuze’s account, understands experience itself as a reception of signs by a proto-subject which must be understood properly, just as the large variety of images discussed in Cinema 1 and 2 are categorised by Deleuze on the basis of C.S. Peirce’s semiotics.

Deleuze often comes to consider the questions ‘what is the nature of the artist, and of art?’ Aside from his specific elaborations of these questions in What is Philosophy?, he is concerned to emphasise the radically active creative nature of art and artists in his work in general. This characterisation goes far beyond the general consideration of artists as ‘creative people’, and highlights the manner in which art is itself a creation of movement, not of representations: that is, something radically new, an affect, a movement of force or desire (cf. PS xi.,187 n1).

While the dominant Western tradition, from Plato to Heidegger, places art in a relationship to truth, Deleuze insists in every case on a Nietzschean argument (NP 102-3), that the work of art only has relations with forces, and that truth is a derivative, secondary formation: art is active.

In another register, Deleuze suggests that artists are themselves created, within thought, and must be cultured and afflicted by forces which exceed them to develop to the point of creativity (NP 103-9; cf. (4)(d) above). These forces, in turn, account for the frequent frailty of artists and thinkers. While the work of art sets to work forces of life, the artist themselves has experienced “too much”, and this wearies and sickens them (D 18; C2 189).

Deleuze’s insistences that the artist is above all someone who creates new ways of being and perceiving increases in frequency and strength throughout the course of his texts on art and artists.

a. Literature

Deleuze wrote extensively on literature throughout his career. Aside from dedicating whole works to Proust (Proust and Signs 1964), Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (“Coldness and Cruelty”1969), and Kafka (Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature 1975), and a large portion of The Logic of Sense to Lewis Carroll, he also dealt in some detail with a wide range of figures such as F. Scott Fizgerald, Herman Melville, Samuel Beckett, Antonin Artaud, Heinrich von Kleist, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

i. Marcel Proust

It is quite easy, if one wishes to attach a philosophical point of view to Marcel Proust’s work, to see it as a phenomenology of memory and perception, in which his famous text In Search of Lost Time would be oriented towards an understanding of what underlies and gives substance to experience and memory.

In essence, Deleuze proposes the opposite of the phenomenological method. He reads Proust’s work as an anti-logos, that supposes, rather than a transcendental ego which is the necessary feature of all experience, a passive, receptive subject at the mercy of the signs and symptoms of the world.

For what does in fact take place in In Search of Lost Time, one and the same story with infinite variations? It is clear that the narrator sees nothing, hears nothing . . like a spider poised in its web, observing nothing, but responding to the slightest sign . . . (AO 68)

Rather than memory, the central question of the Search, being based within the subject, and as the product of certain transcendental operations, it is a creation of something which did not exist before by way of an original, each-time unique, style of interpretation for experiences (PS 101). Deleuze uses the term ‘anti-logos’ on the grounds that Proust, as he argues, refuses the representational model of experience central to Western philosophy:

Everywhere Proust contrasts the world of signs and symptoms with the world of attributes, the world of hieroglyphs and ideograms with the world of analytic expression, phonetic writing, and rational thought. What is constantly impugned are the great themes inherited from the Greeks: philos, sophia, dialogue, logos, phone. (PS 108)

In contrast, Deleuze characterises the Search as a recasting of thought: thought is creative and not reminiscent (Platonic and phenomenological).

ii. Leopold von Sacher-masoch

Masoch features in a few of Deleuze’s books (K 66-7; D 119-23), but most significantly in his long study “Coldness and Cruelty”. This early text is a critique of the unity of the clinical and aesthetic notion “sado-masochism”.

Deleuze argues here that this clinical concept fails to account for the actual writings of the Maquis de Sade and Sacher-masoch, along with making an unjustified unity from a two quite distinct groups of symptoms.

Masoch is considered by Deleuze to be an important writer of unusual power, and a master of suspense, the key literary element of masochism. However, while de Sade has become well-known, and his writings analysed, Deleuze suggests that our poor understanding of Masoch’s texts is one of the main culprits in making the confused unity that is sadomasochism. In fact, according to Deleuze, he offers us a new way of understanding existence by displacing sexuality into the world of power (M 12). Thus, Deleuze tells us, Masoch was in fact, “a great anthropologist.” (M 16)

Point by point, Deleuze develops a reading of the two writers, Masoch in particular, that shows their profound disparity. Alongside this is an analysis of the psychiatric categories of sadism and masochism that reveals the same lack of common ground.

Sadomasochism is one of these misbegotten names, a semiological howler. We found in every case that what appeared to be a common ‘sign’ linking the two perversions together turned out on investigation to be in the nature of a mere syndrome which could be further broken down into irreducibly specific symptoms of the one or the other perversion. (M 134)

In “Coldness and Cruelty”, Deleuze also elaborates a critique of Freud that points in the direction of Anti-Oedipus, although clearly more limited in scope.

iii. Franz Kafka

Kafka: towards a minor literature can be distinguished from Deleuze’s other texts on literature in that it was written with Guattari, and it strongly bears the stamp of Anti-Oedipus, published just three years earlier, and the concepts utilised there. In many ways, it can be read as a development of the same themes in regard to Kafka’s work.

This text is a marked departure from all of the dominant interpretations of Kafka’s writing, which is generally considered either psychoanalytically (as a projection of interior guilt onto the world through writing) or mythically, that is, as a reserve of symbols and closely related to negative theology and Jewish mysticism. Deleuze and Guattari consider Kafka as a proponent of a joyful science, of writing as a way of creating a line of flight or freedom from the forms of domination. They write:

The three worst themes in many interpretations of Kafka are the transcendence of the law, the interiority of guilt, the subjectivity of enunciation. (K 45)

In contrast, Deleuze and Guattari read Kafka as a proponent of the immanence of desire. The law is no more than a secondary configuration that traps desire into certain formations: bureaucracy, of course, is the main example in Kafka’s work, where offices, secretaries, lawyers and bankers present figures of entrapment.

They also see Kafka as directly targeting the Oedipus complex, the triangle of “daddy-mommy-me”:

the too-well formed family triangle is really only a conduit for investments of an entirely different sort that the child endlessly discovers underneath his father, inside his mother, in himself. The judges, commissioners, bureaucrats, and so on, are not substitutes for the father; rather, it is the father who is a condensation of all these forces that he submits to and that he tries to get his son to submit to. (K 11-2)

Thus, for Kafka, according to Deleuze and Guattari, the family are a socially derived unit that works by trapping the flow of desire. The interiority of guilt is replaced by the exteriority of subjugation. This is best demonstrated in the analysis of Kafka’s famous short story, The Metamorphosis (K 14-5).

They also wish to read Kafka, not as a writer of genius, who expresses the superior insight of his inner sight, but as a writer of minor literature. This is the key concept of Deleuze and Guattari’s reading of Kafka. Minor literature is a writing that takes a dominant language (German, in Kafka’s case, French in Beckett’s, and so forth), and pushes it until it becomes a language of force, and not of signification (K 19). In turn, this connects immediately with the situation of minorities, minority groups in the first instance, but also the attempts that everyone makes to create a line of flight outside of majoritarian or molar social formations.

As such, minor literature is an immediately political writing (K 17), which connects the text immediately to (micro-) political struggle. Thus the third substitution is the collective, that is, political, nature of enunciation, for the traditional model of the subjective intent behind the author’s words. Kafka, for Deleuze and Guattari, writes as a node in a field of forces, rather than a Cartesian cogito, sovereign in the castle of consciousness. “The superiority of Anglo-american literature”

One clear feature of Deleuze’s relationship to literature is his outspoken appreciation for what he calls Anglo-American literature, and its superiority over the literature of Europe.

What we find in great English and American novelists is a gift, rare among the French, for intensities, flows, machine-books, tool-books, schizo-books. (N 23)

The great European tradition in literature is analogous for Deleuze to traditional philosophy: it always revolves around a relationship to truth, the preservation of some kind of social status quo, the sovereignty of the author over the text; as Deleuze states, “everybody says “cogito” in the French novel.”

The strength of Anglo-american literature for Deleuze is rather that it rejects the idea of the book as a representation of reality, and all of the adjacent problems with the dogmatic image of literature, and presents the book as a machine, as something which does things, rather than signifying.

b. Cinema

Part of the reason for the impact of Deleuze’s writings on cinema is simply that he is the first important philosopher to have devoted such detailed attention to it. Of course, many philosophers have written about movies, but Deleuze offers an analysis of the cinema itself as an artistic form, and develops a number of connections between it and other philosophical work.

Deleuze’s first book is entitled Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. It deals with cinema from its development through to the second World War. For Deleuze, the cinema as an art form is quite unique, and deals with its subject matter in ways that no other form of art is capable of, particularly as a way of relating to the experience of space and time.

Deleuze’s analysis begins by coming to new understandings of the concepts of the image and movement. The image, above all, is not a representation of something, that is, a linguistic sign. This definition relies upon the age-old Platonic distinction between form and matter, in its modern Saussurean form of signifier-signified. Rather, Deleuze wants to collapse these two orders into one, and the image thus becomes expressive and affective: not an image of a body, but the body as image (C1 58).

This collapse comes about with reference to two philosophers, Henri Bergson and Charles Sanders Peirce. Deleuze dedicated a book-length study to the former entitled Bergsonism (1968), and his use of his notions of movement and time in the Cinema texts is already presaged by this text. Movement for Bergson, Deleuze argues, is not separable from the object which moves: they are literally the same thing. Thus, no representative relationship can be established without artificially halting the flow of movement and thus misconstruing the frozen ‘element’ as self-sufficient. There is only the flow of movement which expresses itself in different ways. Among other things, this is one of Deleuze’s critiques of phenomenology (C1 56, 60). Thus the early cinema is characterised for Deleuze by the reign of what he calls the sensory-motor schema. This schema is the unity of the viewed and the eye that views in dynamic movement.

This model of the movement-image is precisely the nature of cinema, for Deleuze. It does not falsify movement by extracting segments and stringing them together in a representative fashion, but creates a wide range of expressive images. It is in order to come to terms with the varieties of movement-images that Deleuze turns to Peirce, who developed, “the most extraordinary classifications of images and signs . . .” (C2 30). The main part of Cinema 1 is thus devoted to using, with some alterations, Peirce’s semiotic classifications to describe the use of movement-images in cinema, and their centrality before the second World War.

The movement from the first text to Cinema 2: The Time-Image has a significance closely related to Kant’s so-called Copernican revolution in philosophy. Up until Kant, time was subject to the events that took place within it, time was a time of seasons and habitual repetition (see (3)(c) above); it was not able to be considered on its own, but as a measure of movement (C2 34-5; KCP iv.). One element of Kant’s achievement for Deleuze, as we have seen, is his reversal of the time-movement relationship: he establishes time itself as an element to which movement must be subordinated, a pure time.

In the cinema, Deleuze argues, a similar reversal takes place. The historico-cultural reason behind this reversal is the event of World War two itself. With the great truths of Western culture put so deeply in question by the before unimaginable methods employed and their forthcoming results, the sensory-motor apparatus of the movement-image are made to tremble before the unbearable, the too-much of life’s possibilities, the potential of the present (C2 35). No longer could the dogmatic truths that had guided society, and cinema to an extent, allow the apparently ‘natural’ movement from one thing to the next in an habitual fashion: ‘natural’ links precisely lost their efficacy. And with the use of unnatural or false links, which do not follow the sequence or narrative affect of the movement-image, time itself, the time-image, is manifested in cinema (Deleuze considers Orson Welles to be the first auteur to make use of the time-image (C2 137)). Rather than finding time as an, “indirect representation,” (C2 35-6), the viewer experiences the movement of time itself, which images, scenes, plots and characters presuppose or manifest in order to gain any sort of movement whatsoever.