Epistemic Circularity

An epistemically circular argument defends the reliability of a source of belief by relying on premises that are themselves based on the source. It is a widely shared intuition that there is something wrong with epistemically circular arguments.

William Alston, who first used the term in this sense, argues plausibly that there is no way to know or to be justified in believing that our basic sources of belief–such as perception, introspection, intuitive reason, memory and reasoning–are reliable except by using such epistemically circular arguments. And many contemporary accounts of knowledge and justification allow our gaining knowledge and justified beliefs by relying on such arguments. Indeed, any account that accepts that a belief source can deliver knowledge (or justified beliefs) prior to one’s knowing (or believing justifiably) that the source is reliable allows this. It allows our knowing the premises of an epistemically circular argument without already knowing the conclusion, and using the argument for attaining knowledge of the conclusion. Still, we have the intuition that any such account makes knowledge too easy.

In order to avoid too easy knowledge via epistemic circularity, we need to assume that a source can yield knowledge only if we first know that it is reliable. However, this assumption leads to the ancient problem of the criterion and the danger of landing in radical skepticism. Skepticism could be avoided if our knowledge about reliability were basic or noninferential. It could also be avoided if we had some sort of “non-evidential” entitlement to taking our sources to be reliable. Both options are problematic.

One might think that we have to allow easy knowledge and some epistemic circularity because it is the only way to avoid skepticism. If we do so, however, we still need to explain what is then wrong with other epistemically circular arguments. One possible explanation is that they fail to be dialectically effective. You cannot rationally convince someone who doubts the conclusion of the epistemically circular argument, because such a person also doubts the premises. Another possible explanation is that such arguments fail to defeat a reliability defeater: if you have a reason to believe that one of your sources of belief is unreliable, you have a defeater for all beliefs based on the source. You cannot defeat this defeater and regain justification for these beliefs by means of epistemically circular arguments. Yet, there are still disturbing cases in which you do not doubt the reliability of a source; you are just ignorant of it. The present account allows your gaining knowledge about the reliability of the source too easily.

Thus there seems to be no completely satisfactory solution to the problem of epistemic circularity. This suggests that the ancient problem of the criterion is a genuine skeptical paradox.

Table of Contents

- Alston on Epistemic Circularity

- Epistemic Failure

- Easy Knowledge and the KR Principle

- Coherence and Reflective Knowledge

- The Problem of the Criterion

- Basic Reliability Knowledge

- Wittgenstein, Entitlement and Practical Rationality

- Sensitivity

- Dialectical Ineffectiveness and the Inability to Defeat Defeaters

- Epistemology and Dialectic

- References and Further Reading

1. Alston on Epistemic Circularity

When Descartes tried to show that clear and distinct perceptions are true by relying on premises that are themselves based on clear and distinct perceptions, he was quickly made aware that there was something viciously circular in his attempt. It seems that we cannot use reason to show that reason is reliable. Thomas Reid [1710-1796] (1983, 276) pointed out that such an attempt would be as ridiculous as trying to determine a man’s honesty by asking the man himself whether he was honest or not. Such a procedure is completely useless. Whether he were honest or not, he would of course say that he was. All attempts to show that any of our sources of belief is reliable by trusting its own verdict of its reliability would be similarly useless.

The most detailed characterization of this sort of circularity in recent literature is given by William Alston (1989; 1991; 1993), who calls it “epistemic circularity.” He argues that there is no way to show that any of our basic sources of belief–such as perception, intuitive reason, introspection, memory or reasoning–is reliable without falling into epistemic circularity: there is no way to show that such a source is reliable without relying at some point or another on premises that are themselves derived from that source. Thus we cannot have any noncircular reasons for supposing that the sources on which we base our beliefs are reliable. What kind of circularity is this?

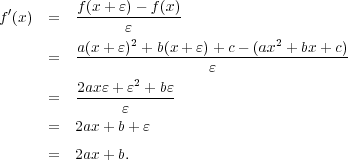

Alston (1989; 1993, 12-15) takes sense perception as an example. If we wish to show that sense perception is reliable, the simplest and most fundamental way is to use a track-record argument. We collect a suitable sample of beliefs that are based on sense perception and take the proportion of truths in the sample as an estimation of the reliability of that source of belief. We rely on the following inductive argument:

At t1, S1 formed the perceptual belief that p1, and p1 is true.

At t2, S2 formed the perceptual belief that p2, and p2 is true.

.

.

.At tn, Sn formed the perceptual belief that pn, and pn is true.

Therefore, sense perception is a reliable source of belief.

How are we to determine whether the particular perceptual beliefs mentioned in the premises are true? The only way seems to be to form further perceptual beliefs. Thus the premises of the track-record argument for the reliability of sense perception are themselves based on sense perception. The kind of circularity involved in this argument is not logical circularity because the conclusion that sense perception is reliable is not used as one of the premises. Nevertheless, we cannot consider ourselves justified in accepting the premises unless we assume that sense perception is reliable. Since this kind of circularity involves commitment to the conclusion as a presupposition of our supposing ourselves to be justified in accepting the premises, Alston calls it epistemic circularity.

Epistemic circularity is thus not a feature of the argument as such. It relates to our attempt to use the argument to justify the conclusion or to arrive at a justified belief by reasoning from the premises to the conclusion. In order to succeed, such attempts require that we be justified in accepting the premises. According to Alston, we cannot suppose ourselves to be justified in holding the premises unless we somehow assume the conclusion. He explains our commitment to the conclusion dialectically: “If one were to challenge our premises and continue the challenge long enough, we would eventually be driven to appeal to the reliability of sense perception in defending our right to those premises.¨ (1993, 15)

Surprisingly, Alston (1989; 1993, 16) argues that epistemic circularity does not prevent our using an epistemically circular argument to show that sense perception is reliable or to justify the claim that it is. Neither does it prevent our being justified in believing or even knowing that sense perception is reliable. This is so if there are no higher-level requirements for justification and knowledge, such as the requirement that we be justified in believing that sense perception is reliable. If we can have justified perceptual beliefs without already being justified in believing that sense perception is reliable, we can be justified in accepting the premises of the track-record argument and using it for attaining justification for the conclusion.

Alston does not suggest that there are higher-level requirements for knowledge and justification. His account of justification is a form of generic reliabilism that do not make such requirements. According to such reliabilism,

S’s belief that p is justified if and only if it has a sufficiently reliable causal source.

If reliabilism is true, we can very well be justified in believing the premises of the track-record argument without being justified in believing the conclusion. It merely requires that the conclusion be, in fact, true. If sense perception is reliable along with other relevant sources–such as introspection and inductive reasoning–we can be justified in accepting the premises and thus arrive at a justified belief in the conclusion by reasoning inductively from the premises. Moreover, nothing prevents our coming to know the conclusion by means of such reasoning.

What, then, is wrong with epistemically circular arguments? This is what Alston states:

Epistemic circularity does not in and of itself disqualify the argument. But even granting this point, the argument will not do its job unless we are justified in accepting its premises; and that is the case only if sense perception is in fact reliable. This is to offer a stone instead of bread. We can say the same of any belief-forming practice whatever, no matter how disreputable. We can just as well say of crystal ball gazing that if it is reliable, we can use a track-record argument to show that it is reliable. But when we ask whether one or another source of belief is reliable, we are interested in discriminating those that can be reasonably trusted from those that cannot. Hence merely showing that if a given source is reliable it can be shown by its record to be reliable, does nothing to indicate that the source belongs to the sheep rather that with the goats. (1993, 17)

This is puzzling. Earlier Alston grants that, assuming reliabilism, we can use an epistemically circular track-record argument to show that sense perception is reliable. Now he is suggesting that such an argument shows at most the conditional conclusion that if a given source is reliable it can be shown by its record to be reliable. This seems merely to contradict the point he already granted.

We can make sense of this if we distinguish between two kinds of showing. When Alston talks about showing he usually has in mind something we could call “epistemic showing.” Showing in this sense requires a good argument with justified premises. If we have such an epistemically circular argument for the reliability of sense perception, we can show the categorical conclusion that sense perception is reliable. Assuming that reliabilism is true and that sense perception, introspection and induction are reliable processes, the premises of the track-record argument are surely justified, and the justification of the premises is transmitted to the conclusion. If this is all that is required for showing, then epistemic circularity does not disqualify the argument.

There is another sense of showing, that of “dialectical showing.” Showing in this sense is relative to an audience, and it requires that we have an argument that our audience takes to be sound, otherwise we would be unable to rationally convince it. If we assume that our audience is skeptical about the reliability of sense perception, it is clear that we cannot convince such an audience with an epistemically circular argument. This is so because the audience would also be skeptical about the truth of the premises. Assuming that our audience is skeptical only about perception and not about introspection and induction, we can only show to such an audience Alston’s hypothetical conclusion: if sense perception is reliable, we can show–in the epistemic sense–that it is.

Whether this is what Alston has in mind or not, it is one possible diagnosis of the failure of epistemically circular arguments. Although they may provide justification for our reliability beliefs, they are unable to rationally remove doubts about reliability. They are not dialectically effective against the skeptic.

2. Epistemic Failure

The problem of epistemic circularity derives from our intuition that there is something wrong with it. Many philosophers have expressed doubts that this intuition is completely explained by dialectical considerations. The fault seems to be epistemic rather than just dialectical. Richard Fumerton (1995) and Jonathan Vogel (2000) argue that we cannot gain knowledge and justified beliefs by means of epistemically circular reasoning. They conclude that any account of knowledge or justification that allows this must be mistaken. Their target is reliabilism in particular. Fumerton writes:

You cannot use perception to justify the reliability of perception! You cannot use memory to justify the reliability of memory! You cannot use induction to justify the reliability of induction! Such attempts to respond to the skeptic’s concerns involve blatant, indeed pathetic, circularity. Frankly, this does seem right to me and I hope it seems right to you, but if it does, then I suggest you have a powerful reason to conclude that externalism is false. (1995, 177)

If the mere reliability of a process is sufficient for giving us justification, as reliabilism entails, then we can use it to obtain a justified belief even about its own reliability. According to Fumerton, this counterintuitive result shows that reliabilism is false.

Vogel (2000, 613-623) gives the example of Roxanne, who has a car with a highly reliable gas gauge and who believes implicitly what the gas gauge indicates, without knowing that it is reliable. In order to gain knowledge about the reliability of the gauge, she undertakes the following procedure. She looks at the gauge often and forms a belief not only about how much gas there is in the tank, but also about the reading of the gauge. For example, when the gauge reads ‘F’, she believes both that the gauge reads ‘F’ and that the tank is full. She combines these beliefs into the belief:

(1) On this occasion, the gauge reads ‘F’ and the tank is F.

Surely, the perceptual process by which Roxanne forms her belief about the reading of the gauge is reliable, but so is, by hypothesis, the process through which she reaches the belief that the tank is full. Roxanne’s belief in (1) is thus the result of a reliable process. She then repeats this process on several occasions and forms beliefs of the form:

(2) On this occasion, the gauge reads ‘X’ and the tank is X.

From a representative set of such beliefs, she concludes inductively that:

(3) The gauge is reliable.

Because induction is also a reliable process, the whole process by which Roxanne reaches her conclusion is reliable. Thus reliabilism allows that in this way she gains knowledge that the gauge is reliable.

Vogel assumes that this process, which he calls bootstrapping, is illegitimate and concludes that reliabilism goes wrong in improperly ratifying bootstrapping as a way of gaining knowledge.

We have an intuition that there is something wrong with this sort of epistemically circular reasoning. Here, it is difficult to explain the intuition in terms of some sort of dialectical failure because there is nobody who is questioning the reliability of the gauge and who needs to be convinced about the matter. It is merely assumed that Roxanne did not originally know that it was reliable. It follows from reliabilism that she can gain this knowledge by this sort of bootstrapping, which is contrary to our intuitions.

3. Easy Knowledge and the KR Principle

Epistemic circularity is not only a problem for reliabilism. As Alston pointed out, any epistemological theory that does not set higher-level requirements for knowledge or justified belief is bound to allow epistemic circularity. The problem is that such a theory makes knowledge and justified belief about reliability intuitively too easy.

Stewart Cohen (2002) argues that any theory that rejects the following principle allows knowledge about reliability too easily:

KR: A potential knowledge source K can yield knowledge for S, only if S knows K is reliable.

Theories that reject this KR principle allow that a belief source can deliver knowledge prior to one’s knowing that the source is reliable. Cohen calls such knowledge “basic” knowledge. (Note that he uses the phrase in a nonstandard way.) Theories that allow for basic knowledge can appeal to our basic knowledge in order to explain how we know that our belief sources are reliable:

According to such views, we first acquire a rich stock of basic knowledge about the world. Such knowledge, once obtained, enables us to learn how we are situated in the world, and so to learn, among other things, that our belief sources are reliable. (2002, 310)

In obtaining such knowledge of reliability we reason in a way that is epistemically circular. The problem is that we gain knowledge too easily.

It is not only reliabilism that rejects the KR principle: there are other currently popular theories that do so. For example, evidentialism makes knowledge a function of evidence. An evidentialist who denies the KR principle allows that one can know that p on the basis of evidence E without knowing that E is a reliable indication of the truth of p. Such evidentialism allows our gaining knowledge of reliability through epistemically circular reasoning.

However, the principle does not seem to be strong enough because even some theories that accept it do not avoid epistemic circularity, and thus make knowledge too easy. The KR principle, as Cohen formulates it, does not make any requirements about epistemic order. It does not require in particular that knowledge about the reliability of source K be prior to (or independent of) knowledge based on K. It allows that we gain both kinds of knowledge simultaneously.

4. Coherence and Reflective Knowledge

According to holistic coherentism, knowledge is generated simultaneously in the whole system of beliefs once a sufficient degree of coherence is achieved. It is clear that meta-level beliefs about the sources of belief and their reliability can increase the coherence of the whole system of beliefs. So coherentism that requires such a meta-level perspective into the reliability of the sources of belief satisfies the KR principle: I can know that p only if I also know that the source of my belief that p is reliable.

However, as James Van Cleve (2003, 55-57) points out, coherentism does not avoid the problem of easy knowledge. It allows that we gain knowledge through epistemically circular reasoning. The steps by which we gain such knowledge may be exactly the same as in the foundationalist version. The only difference is that when, according to foundationalism, knowledge is first generated in the premises and then transmitted to the conclusion, coherentism makes it appear simultaneously in the premises and in the conclusion. The fact that knowledge is not generated in the premises until the conclusion is reached does not make it less easy to attain knowledge.

Ernest Sosa (1997) suggests that we can resolve the problems of circularity by his distinction between animal knowledge and reflective knowledge, but as both Cohen (2002, 326) and Van Cleve (2003, 57) point out, Sosa’s account allows knowledge about reliability too easily. Animal knowledge is knowledge as it is understood in simple reliabilism: it requires just a true and reliably formed belief. So it does not satisfy the KR principle and allows easy knowledge. We can attain animal knowledge about the reliability of a source through epistemically circular reasoning.

Sosa’s point is that reflective knowledge satisfies the principle. In addition to animal knowledge, it requires a coherent system of beliefs that includes an epistemic perspective into the reliability of the sources of belief. So a source delivers reflective knowledge for me only if I know that the source is reliable, yet it is still true that the epistemically circular track-record argument provides all the ingredients needed for such reflective knowledge. I attain animal knowledge about the reliability of perception by reasoning from my animal knowledge about the truth of particular perceptual beliefs. Once I have attained this knowledge, my system of beliefs also achieves a sufficient degree of coherence that transfers my animal knowledge into reflective knowledge. All this happens still too easily. It happens in fact as easily as before. The only difference is the points at which different sorts of knowledge are attained. The reasoning itself is exactly the same.

It seems that we can avoid allowing easy knowledge only by strengthening the KR principle. It must require that knowledge of the reliability of source K be prior to knowledge based on K. We must know that the source is reliable independently of any knowledge based on the source. The problem with coherentism and Sosa’s account is that they reject this strengthened KR principle, and this is why they make knowledge too easy.

5. The Problem of the Criterion

By affirming the strengthened KR principle we avoid the easy-knowledge problem but are in danger of falling into skepticism. The strengthened principle leads to the ancient problem of the criterion.

Ancient Pyrrhonian skeptics were puzzled about the disagreements that prevailed about any object of inquiry. They insisted that, in order to resolve these disagreements and to attain any knowledge, we need criteria that distinguish beliefs that are true from those that are false. However, there are also disagreements about the right criteria of truth. In order to resolve these disagreements and to know what the right criteria are, we need to know already which beliefs are true–the ones the criteria are supposed to pick out. We are thus caught in a circle.

If we understand the right criteria of truth as reliable sources of belief–sources that mostly produce true beliefs–we arrive at the following formulation of the problem of the criterion:

(1) We can know that a belief based on source K is true only if we first know that K is reliable.

(2) We can know that K is reliable only if we first know that some beliefs based on source K are true.

Assumption (1) is a formulation of the strengthened KR principle. Together with assumption (2), it leads to skepticism: we cannot know which sources are reliable nor which beliefs are true. To be sure, (2) does not require us to know that beliefs based on K are true through K itself; we can rely on some other source. However, (1) posits that this other source can deliver knowledge only if we first know that it is reliable, and (2) that, in order to know this, we need to know that some beliefs based on it are true. In order to know this, in turn, we once again have to rely on some third source, and so on. Because we cannot have an infinite number of sources, sooner or later we have to rely on sources already relied on at some earlier point. We are thus reasoning in a circle, and circular reasoning is unable to provide knowledge.

The circle we are caught in is not epistemic. It is a straightforwardly logical circle. It is clear that a logical circle does not produce knowledge. Such a circle is nowhere connected to reality. Thus in trying to avoid epistemic circularity, we are caught in a more clearly vicious circle–a logical circle.

It is natural to think that epistemic circularity is the lesser evil. If we only have the alternatives of making knowledge too easy or impossible, most philosophers would surely choose the former. This may be the motivation behind currently popular reliabilist and evidentialist epistemologies that deny higher-level requirements for knowledge, but are these really our only options? Could we not reject assumption (2) instead of (1)?

6. Basic Reliability Knowledge

One might concede that a source can give us knowledge only if we first know that it is reliable, but still deny that this knowledge of reliability must in turn be inferred from some other knowledge. One might insist instead that our knowledge about our own reliability is basic or noninferential. This would break the skeptic’s circle.

Thomas Reid (1983, 275) seems to be the traditional advocate of this position. He takes it as a first principle that our cognitive faculties are reliable. He states that first principles are self-evident: we know them directly without deriving them from some other truths (257). How is it possible to know directly a generalization that is only contingently true? It may be easy to see how we can directly know a generalization, such as “All triangles have three angles,” which is a necessary truth: we can simply see its truth through a priori intuition. However, we cannot simply see that our faculties are reliable. The faculty of a priori reason does not give us knowledge of contingent generalizations.

Reid (259-260) posits that there is a special faculty for knowing the first principles, which he calls common sense. Thus, common sense tells us that our faculties are reliable. However, it cannot give us knowledge unless we first know that it is reliable. How can we know this? The only available answer seems to be that we also know this through common sense. (Bergmann 2004, 722-724) There is a serious problem if we assume the skeptic’s strengthened KR principle. This entails that we can know that common sense is reliable only if we first know that it is reliable. We must know it before we know it, which is impossible. We avoid this result if we go back to Cohen’s original KR principle (Van Cleve, 2003, 50-52), but then we face epistemic circularity once again.

According to the Reidian view, knowledge about the reliability of our faculties is basic, and the source of it is common sense. However, common sense delivers this knowledge only if it is itself known to be reliable. If we accept Cohen’s original KR principle and deny the skeptic’s requirement that this knowledge be prior to other knowledge delivered by common sense, we allow that common sense delivers simultaneously basic knowledge about the reliability of our faculties and about the reliability of common sense itself. This is a coherent position.

However, this Reidian view allows one kind of epistemic circularity. Although it is not quite the same kind as in the track-record argument, it allows that we can know that a faculty is reliable by using that very same faculty. The only difference is that this is basic knowledge and not knowledge based on reasoning. It seems that this view makes knowledge about reliability even easier than before.

If we wanted to determine whether to trust a guru, we could construct an inductive argument based on the premises about the truth of what he says and leading to the conclusion that he is reliable. If our belief in the premises is itself based on what he tells us, our argument is epistemically circular. It seems that this cannot be a way of gaining knowledge about his reliability in that it would be intuitively too easy. It would be even easier to base our belief in his reliability on his simply saying that he is reliable. If we cannot gain knowledge through epistemically circular reasoning, how could we gain it by taking this more direct route?

7. Wittgenstein, Entitlement and Practical Rationality

Let us grant that we somehow presuppose the reliability of our sources of belief when we form and evaluate beliefs. What kind of normative status do these presuppositions have if they cannot have the status of basic knowledge? Many philosophers have been inspired by Wittgenstein’s last notebooks published as On Certainty (1969, §§ 341-343):

K the questions that we raise and our doubts depend upon the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were like hinges on which they turn.

That is to say, it belongs to the logic of our scientific investigations that certain things are indeed not doubted.

But it isn’t that the situation is like this: We just can’t investigate everything, and for that reason we are forced to rest content with assumption. If I want the door to turn, the hinges must stay put.

The idea is that in every context of inquiry there are certain propositions that are not and cannot be doubted. They are the hinges that must stay put if we are to conduct inquiry at all. According to Wittgenstein, these hinge propositions cannot be justified, neither can we know them. They are the presuppositions that make justification and knowledge possible.

Wittgenstein (§§ 163, 337) suggests that such hinge propositions include propositions about the reliability of our sources of belief. This explains why we cannot gain knowledge about reliability through epistemically circular reasoning, because we cannot have such knowledge at all. Wittgenstein may have thought so because he took hinge “propositions¨ to have no factual content and thus to be neither true nor false. Thus our concepts of knowledge and justification would not apply to them. However, this view is not very intuitive. Surely the sentence “Sense perception is reliable” appears to express a genuine proposition that is either true or false. If it does express such a proposition, we can have doxastic attitudes to the proposition, and these attitudes can be evaluated epistemically.

Crispin Wright (2004) follows Wittgenstein but takes hinge propositions to be genuine propositions that are epistemically evaluable. He provides an account of the structure of justification that explains why the justification of the premises in certain valid arguments does not transmit to the conclusion. Although the epistemically circular track-record argument is an inductive argument, the same account explains the transmission failure here.

According to Wright’s account, we cannot be justified in accepting the premises of Alston’s track-record argument unless we are already justified in accepting the conclusion that sense perception is reliable. This is why the justification we may have for the premises does not transmit to the conclusion: it presupposes a prior justification for the conclusion. Thus Wright accepts a version of the skeptic’s strengthened KR principle, which effectively blocks epistemically circular reasoning.

He then tries to avoid skepticism by distinguishing between ordinary evidential justification and non-evidential justification he calls “entitlement.” In order to form justified perceptual beliefs, we must already be entitled to take it for granted that sense perception is reliable. However, because this entitlement is a kind of unearned justification that requires no evidential work, we can break the skeptic’s circle.

Wright’s entitlement is not based on sources of justification, such as perception, introspection, memory or reasoning. We get it by default, which is why the KR principle does not apply to it. Thus it avoids the problem of the Reidian account.

Unfortunately, it has its own problems. One of these concerns the nature of entitlement. According to Wright, it is a kind of rational entitlement, but what kind is it? This is how he comments on certain of Wittgenstein’s passages:

I take Wittgenstein’s point in these admittedly not unequivocal passages to be that this is essential: one cannot but take certain such things for granted. (2004, 189)

This line of reply concedes that the best sceptical arguments have something to teach us–that the limits of justification they bring out are genuine and essential–but then replies that, just for that reason, cognitive achievement must be reckoned to take place within such limits. The attempt to surpass them would result not in an increase in rigour or solidity but merely in cognitive paralysis. (2004, 191)

Wright argues here that we cannot but take certain things for granted. In order to engage in inquiry and to form justified beliefs, one must accept certain presuppositions. Refusing to do that would mean cognitive paralysis. As Duncan Pritchard (2005) comments, this seems to be a defense of the practical rationality of assuming that the sources of one’s beliefs are reliable. Nothing is said for the truth of those presuppositions or of the epistemic rationality of accepting them.

Alston defends more explicitly the practical rationality of taking our sources of belief to be reliable:

In the nature of the case, there is no appeal beyond the practices we find ourselves firmly committed to, psychologically and socially. We cannot look into any issue whatever without employing some way of forming and evaluating beliefs; that applies as much to issues concerning the reliability of doxastic practices as to any others. Hence there is no alternative to employing the practices we find to be firmly rooted in our lives, practices we could abandon or replace only with extreme difficulty if at all. (1993, 125)

Alston adds that the suspension of all belief is not an option, and that there is no reason to substitute our firmly established doxastic practices for some new ones because neither would there be any noncircular defense of these new practices. Alston makes it quite clear that this is a defense of the practical rationality of engaging in firmly established practices and taking them to be reliable.

However, this defense of the practical rationality of taking our sources of belief to be reliable does not contradict skepticism. In posing the problem of the criterion, the skeptic is not denying the practical rationality of our using the practices that we in fact use. What he or she is denying is the epistemic rationality or justification of the beliefs produced by them. That it would be practically rational for us to assume that the practices are reliable and that they therefore produce justified beliefs is not something the skeptic would deny.

Alston (2005, 240-242) has since rejected this practical validation argument for our sources of belief and settled for a simpler form of Wittgensteinian contextualism. Now he does not tell what kind of entitlement we have to the hinge propositions about the reliability of our sources. Perhaps there is no entitlement, and we just have to blindly trust in their reliability. How, then, does this differ from skepticism?

Curiously enough, neither Wright nor Alston really avoid the allowing of epistemic circularity. Alston even underlines the fact that epistemically circular arguments can produce justification for our beliefs about reliability. His point seems to be that whether this in fact happens is something that we can have only practical reasons for assuming, which does not really explain what is wrong with these arguments.

According to Wright, the justification of the premises does not transmit to the conclusion if it requires that we already be independently justified in accepting the conclusion. However, because this independent justification is a different sort of non-evidential justification–entitlement–it is unclear why the argument fails in transmitting evidential justification. Assuming that the entitlements are already in place–that we are entitled to take introspection, sense perception and inductive reasoning to be reliable–nothing prevents our also gaining evidential justification for the conclusion that sense perception is reliable. At least nothing in Wright’s account does so.

Thus the appeal to default entitlement or practical rationality does not solve our problem: it does not avoid epistemic circularity. At the same time, it may be too concessive to skepticism.

8. Sensitivity

It is possible to reject the KR principle without allowing epistemic circularity. One might simply deny–as Wittgenstein does–that we have any knowledge about our own reliability. One could defend this view–as Wittgenstein does not do–on the basis of the sensitivity condition of knowledge. Analyses of knowledge as defended by Fred Dretske (1971) and Robert Nozick (1981) set the following necessary condition for S‘s knowing that p:

Sensitivity: if it were not true that p, S would not believe that p.

According to Cohen (2002, 316), our beliefs about the reliability of our sources of belief do not satisfy this condition. Assume that we form a belief in the reliability of sense perception on the basis of epistemically circular reasoning. According to the sensitivity condition, we cannot know on this basis that sense perception is reliable if we believed on this basis that it is reliable even if it were not reliable. It seems that this is exactly what is wrong with such arguments: they would cause us to believe that a source is reliable even if it were not. A guru would tell us that he is reliable even if he were not.

The sensitivity condition concerns the possible worlds in which our belief is false but which are otherwise closest to the actual world. Alvin Goldman (1999, 86) suggests that the relevant alternative to the hypothesis that visual perception is reliable is that visual perception is randomly unreliable. If this is the case in the closest possible worlds in which our belief in the reliability of visual perception is false, it may be that we can, after all, know that visual perception is reliable, because in these worlds it would produce a massive amount of inconsistent beliefs, and therefore we would not believe that it is reliable. So, are the worlds in which visual perception is randomly unreliable the closest unreliability worlds? It may be rather that the closest worlds are those in which visual perception is systematically unreliable, and in these worlds we believe that it is reliable. If this is the case, the sensitivity accounts explain very well the intuition that we cannot gain knowledge through epistemically circular reasoning.

Sensitivity accounts of knowledge have not been popular in recent years because they deny the intuitively plausible principle that knowledge is closed under known logical implication. However, as Cohen (2002) has shown, this principle has counterintuitive consequences as does the denial of the KR principle. It allows cases in which we gain knowledge too easily, and perhaps we should therefore accept a sensitivity account that can handle both problems at once. However, a more serious problem is that there are cases of inductive knowledge that do not satisfy the sensitivity condition (Vogel, 1987).

9. Dialectical Ineffectiveness and the Inability to Defeat Defeaters

Arguments are dialectical creatures, so it is natural to evaluate them in terms of their dialectical effectiveness. We have seen already that epistemically circular arguments are poor in this respect. They are not able to rationally convince someone who doubts the conclusion because such a person also doubts the premises. Such arguments therefore fail to be dialectically effective. It could be suggested that this is enough to explain our intuition that there is something wrong with them, and that they need not involve any epistemic failure. (Markie 2005; Pryor 2004)

When it is a question of one’s own self-doubts, we could even allow a kind of epistemic failure. Let us assume that I have doubts about the reliability of my color vision: I believe that my color vision is not reliable, or I have considered the matter and have decided to suspend judgment about it. This doubt is a defeater for my color beliefs: it defeats or undermines my justification for them. Now it seems clear that I cannot defeat this defeater and regain my justification for these beliefs through epistemically circular reasoning. Such reasoning would rely on those very same beliefs for which I have lost the justification. It is unable to defeat reliability defeaters. (Bergmann 2004, 717-720)

We can thus readily explain the failure of epistemically circular arguments in cases in which there are serious doubts about reliability. They fail to remove these doubts. However, as the case of Roxanne shows, dialectical ineffectiveness and the failure to defeat defeaters cannot be the only things that are wrong with epistemic circularity. Neither Roxanne nor anybody else doubts her gas gauge; she is just ignorant about its reliability. She has no knowledge or justified beliefs about the matter. Our intuition is that she cannot gain knowledge or justified beliefs about the reliability of the gauge through the process of bootstrapping.

10. Epistemology and Dialectic

Although the term “epistemic circularity¨ is of recent origin, the phenomenon itself has been well known since the ancient skeptics. Ancient Pyrrhonian skeptics argued that we should suspend belief unless we can resolve the disagreements that there are about any object of inquiry. We could try to resolve these disagreements by relying on reliable sources of belief. Unfortunately, we cannot do this because there is also a disagreement about which sources are reliable, and this disagreement must be resolved first. However, we cannot resolve this disagreement because it would be dialectically ineffective to defend a set of such sources by appealing to premises that are themselves based on them. This is something that the skeptics most emphatically condemned. (Lammenranta 2008)

They also assumed that this sort of failure to resolve disagreements was not merely dialectical. It also prevented our having knowledge. If we should suspend belief about some question, we would certainly not know what the correct answer is. In connecting epistemology closely to dialectic, skeptics were just following the ancient tradition of Plato and Aristotle. This tradition continued in Descartes and early modern philosophy, and seems to be alive even today among the followers of John L. Austin, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Wilfrid Sellars.

In spite of this influential tradition that connects epistemology closely with dialectic, the mainstream of contemporary analytic epistemology takes epistemology to be independent of dialectical issues. Accordingly, we may very well know even if we cannot rationally defend ourselves against those who disagree with us. After all, our sources of belief may, in fact, be reliable, and if this is the case they will provide us with reasons for believing that they are reliable and that those who disagree with us are wrong.

However, most of us have the intuition that it would be too easy to gain knowledge about our own reliability in this way. Perhaps the intuition shows that epistemology is more closely connected to dialectic than is currently acknowledged. This would explain our uneasiness with epistemic circularity and show that the ancient problem of the criterion is a genuine skeptical paradox for which we still lack a plausible solution.

11. References and Further Reading

- Alston, William P. “Epistemic Circularity.¨ Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 47 (1986). Reprinted in Epistemic Justification: Essays in the Theory of Knowledge. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989: 319-349.

- The first and most influential account of the nature and significance of epistemic circularity.

- Alston, William P. The Reliability of Sense Perception. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993.

- Defends the inevitability of epistemic circularity and the practical rationality of engaging in firmly established doxastic practices.

- Alston, William P. Beyond “Justification”: Dimensions of Epistemic Evaluation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005: ch. 11.

- Opts for Wittgensteinian contextualism concerning the status of reliability propositions.

- Bergmann, Michael. “Epistemic Circularity: Malignant and Benign.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 69 (2004): 709-727.

- Explains when epistemically circular arguments do and when they do not provide knowledge about reliability, and defends the Reidian common-sense approach.

- Cohen, Stewart. “Basic Knowledge and the Problem of the Problem of Easy Knowledge.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 65 (2002): 309-329.

- Poses the problem of easy knowledge and tries to avoid epistemic circularity.

- Dretske, Fred, “Conclusive Reasons.¨ Australasian Journal of Philosophy 49 ( 1971): 1-22. Reprinted in Perception, Knowledge and Belief. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2000.

- Defends an early version of the sensitivity condition of knowledge.

- Fumerton, Richard. Metaepistemology and Skepticism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1995: ch. 6.

- Accuses externalism of allowing epistemic circularity.

- Goldman, Alvin I. Knowledge in a Social World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999: section 3.3.

- A Bayesian defense of the epistemic value of epistemic circularity.

- Lammenranta, Markus. “Reliabilism and Circularity.¨ Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 56 (1996): 111-124.

- Relates epistemic circularity to Chisholm’s version of the problem of the criterion.

- Lammenranta, Markus. “Reliabilism, Circularity, and the Pyrrhonian Problematic.¨ Journal of Philosophical Research 28 (2003): 311-328.

- Discusses reliabilist responses to epistemic circularity.

- Lammenranta, Markus. “The Pyrrhonian Problematic.¨ The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism. Ed. John Greco. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Defends the dialectical nature and philosophical importance of the ancient Pyrrhonian problematic.

- Lemos, Noah. “Epistemic Circularity Again.¨ Philosophical Issues 14 (2004): 254ƒ{270.

- Examines and rejects some objections to Sosa’s view that epistemic circularity does not prevent our knowing that our ways of forming beliefs are reliable.

- Markie, Peter. “Easy Knowledge.¨ Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 70 (2005): 406-416.

- Argues that the failure in epistemically circular argument is dialectical rather than epistemic.

- Nozick, Robert. Philosophical Explanations. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass., 1981: ch. 3.

- Defends the sensitivity (tracking) condition of knowledge and formulates the closure-based skeptical argument.

- Pritchard, Duncan. “Wittgenstein’s On Certainty and Contemporary Anti-Scepticism.¨ Readings of Wittgenstein’s On Certainty. Eds. D. Moyal-Sharrock & W. H. Brenner. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005: 189V224.

- Discusses anti-skeptical views deriving from Wittgenstein’s On Certainty.

- Pryor, James. “What’s Wrong with Moore’s Argument?¨ Philosophical Issues14 (2004): 349-378.

- Defends the epistemic respectability of Moore’s proof of the external world.

- Reid, Thomas. Inquiry and Essays. Eds. Ronald E. Beanblossom & Keith Lehrer. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1983.

- An abbreviated edition of Reid’ major works on the philosophy of common sense.

- Schmitt, Frederick F. “What Is Wrong with Epistemic Circularity?¨ Philosophical Issues 14 (2004): 379-402.

- Argues that epistemically circular arguments do have the power of answering doubts about reliability.

- Sosa, Ernest. “Philosophical Scepticism and Epistemic Circularity.¨ Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume 68 (1994): 263-290. Reprinted in Skepticism: A Contemporary Reader. Eds. Keith DeRose & Ted A. Warfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999: 93-114.

- Defends the inevitability and epistemic value of epistemically circular arguments.

- Sosa, Ernest. “Reflective Knowledge in the Best Circles.¨ The Journal of Philosophy 94 (1997): 410-430.

- Uses the distinction between animal knowledge and reflective knowledge to explain why epistemic circles are not vicious.

- Van Cleve, James. “Is Knowledge Easy–or Impossible? Externalism as the Only Alternative to Skepticism.¨ The Skeptics: Contemporary Essays. Ed. Steven Luper. Hampshire: Ashgate, 2003.

- Defends externalism and allowing epistemic circularity as the only alternatives to skepticism.

- Vogel, Jonathan. “Tracking, Closure, and Inductive Knowledge.¨ The Possibility of Knowledge: Nozick and His Critics. Ed. Steven Luper-Foy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1987: 197-215.

- Criticizes the sensitivity condition of knowledge for not allowing inductive knowledge.

- Vogel, Jonathan. “Reliabilism Leveled.¨ The Journal of Philosophy 97 (2000): 602-623.

- Criticizes reliabilism for allowing epistemically circular reasoning.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. On Certainty. Eds. G. E. M. Anscombe & G. H. von Wright. Tr. D. Paul & G. E. M. Anscombe. Oxford: Blackwell, 1969.

- An influential defense of the view that the presuppositions of knowledge are not known.

- Wright, Crispin. “Warrant for Nothing (and Foundations for Free).¨ Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 104 (2004): 167-211.

- Uses the concept of entitlement to resolve skeptical paradoxes.

Author Information

Markus Lammenranta

Email: markus.lammenranta@helsinki.fi

University of Helsinki

Finland

Plato is one of the world’s best known and most widely read and studied philosophers. He was the student of Socrates and the teacher of

Plato is one of the world’s best known and most widely read and studied philosophers. He was the student of Socrates and the teacher of