Simone de Beauvoir (1908—1986)

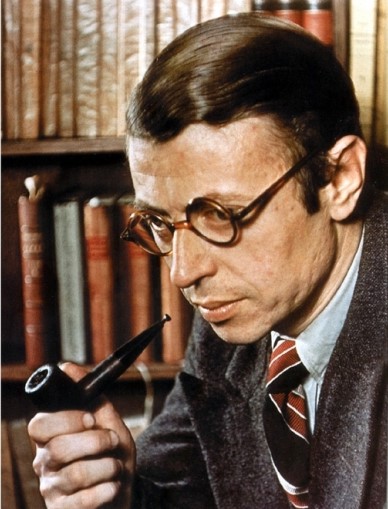

Simone de Beauvoir was one of the most preeminent French existentialist philosophers and writers. Working alongside other famous existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, de Beauvoir produced a rich corpus of writings including works on ethics, feminism, fiction, autobiography, and politics.

Simone de Beauvoir was one of the most preeminent French existentialist philosophers and writers. Working alongside other famous existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, de Beauvoir produced a rich corpus of writings including works on ethics, feminism, fiction, autobiography, and politics.

Beauvoir’s method incorporated various political and ethical dimensions. In The Ethics of Ambiguity, she developed an existentialist ethics that condemned the “spirit of seriousness” in which people too readily identify with certain abstractions at the expense of individual freedom and responsibility. In The Second Sex, she produced an articulate attack on the fact that throughout history women have been relegated to a sphere of “immanence,” and the passive acceptance of roles assigned to them by society. In The Mandarins, she fictionalized the struggles of existents trapped in ambiguous social and personal relationships at the closing of World War II. The emphasis on freedom, responsibility, and ambiguity permeate all of her works and give voice to core themes of existentialist philosophy.

Her philosophical approach is notably diverse. Her influences include French philosophy from Descartes to Bergson, the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, the historical materialism of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and the idealism of Immanuel Kant and G. W. F Hegel. In addition to her philosophical pursuits, de Beauvoir was also an accomplished literary figure, and her novel, The Mandarins, received the prestigious Prix Goncourt award in 1954. Her most famous and influential philosophical work, The Second Sex (1949), heralded a feminist revolution and remains to this day a central text in the investigation of women’s oppression and liberation.

Table of Contents

1. Biography

Simone de Beauvoir was born on January 9, 1908 in Paris to Georges Bertrand de Beauvoir and Françoise (née) Brasseur. Her father, George, whose family had some aristocratic pretensions, had once desired to become an actor but studied law and worked as a civil servant, contenting himself instead with the profession of legal secretary. Despite his love of the theater and literature, as well as his atheism, he remained a staunchly conservative man whose aristocratic proclivities drew him to the extreme right. In December of 1906 he married Françoise Brasseur whose wealthy bourgeois family offered a significant dowry that was lost in the wake of World War I. Slightly awkward and socially inexperienced, Françoise was a deeply religious woman who was devoted to raising her children in the Catholic faith. Her religious, bourgeois orientation became a source of serious conflict between her and her oldest daughter, Simone. [The British refer to Simone de Beauvoir as “de Beauvoir” and the Americans, as “Beauvoir.”]

Born in the morning of January 9, 1908, Simone-Ernestine-Lucie-Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir was a precocious and intellectually curious child from the beginning. Her sister, Hélène (nicknamed “Poupette”) was born two years later in 1910 and Beauvoir immediately took to intensely instructing her little sister as a student. In addition to her own independent initiative, Beauvoir’s intellectual zeal was also nourished by her father who provided her with carefully edited selections from the great works of literature and who encouraged her to read and write from an early age. His interest in her intellectual development carried through until her adolescence when her future professional carrier, necessitated by the loss of her dowry, came to symbolize his own failure. Aware that he was unable to provide a dowry for his daughters, Georges’ relationship with his intellectually astute eldest became conflicted by both pride and disappointment at her prospects. Beauvoir, on the contrary, always wanted to be a writer and a teacher, rather than a mother and a wife and pursued her studies with vigor. Beauvoir began her education in the private Catholic school for girls, the Institut Adeline Désir where she remained until the age of 17. It was here that she met Elizabeth Mabille (Zaza), with whom she shared an intimate and profound friendship until Zaza’s untimely death in 1929. Although the doctor’s blamed Zaza’s death on meningitis, Beauvoir believed that her beloved friend had died from a broken heart in the midst of a struggle with her family over an arranged marriage. Zaza’s friendship and death haunted Beauvoir for the rest of her life and she often spoke of the intense impact they had on her life and her critique of the rigidity of bourgeois attitudes towards women.

Beauvoir had been a deeply religious child as a result of her education and her mother’s training; however, at the age of 14, she had a crisis of faith and decided definitively that there was no God. She remained an atheist until her death. Her rejection of religion was followed by her decision to pursue and teach philosophy. Only once had she considered marriage to her cousin, Jacques Champigneulle. She never again entertained the possibility of marriage, instead preferring to live the life of an intellectual.

Beauvoir passed the baccalauréat exams in mathematics and philosophy in 1925. She then studied mathematics at the Institut Catholique and literature and languages at the Institut Sainte-Marie, passing exams in 1926 for Certificates of Higher Studies in French literature and Latin, before beginning her study of philosophy in 1927. Studying philosophy at the Sorbonne, Beauvoir passed exams for Certificates in History of Philosophy, General Philosophy, Greek, and Logic in 1927, and in 1928, in Ethics, Sociology, and Psychology. She wrote a graduate diplôme on Leibniz for Léon Brunschvig and completed her practice teaching at the lycée Janson-de-Sailly with fellow students, Merleau-Ponty and Claude Lévi-Strauss – with both of whom she remained in philosophical dialogue.

In 1929, she took second place in the highly competitive philosophy agrégation exam, beating Paul Nizan and Jean Hyppolite and barely losing to Jean-Paul Sartre who took first (it was his second attempt at the exam). Unlike Beauvoir, all three men had attended the best preparatory (khâgne) classes for the agrégation and were official students at the École Normale Supérieure. Although she was not an official student, Beauvoir attended lectures and sat for the agrégation at the École Normale. At 21 years of age, Beauvoir was the youngest student ever to pass the agrégation in philosophy and thus became the youngest philosophy teacher in France.

It was during her time at the École Normale that she met Sartre. Sartre and his closed circle of friends (including René Maheu, who gave her her life-long nickname “Castor”, and Paul Nizan) were notoriously elitist at the École Normale. Beauvoir had longed to be a part of this intellectual circle and following her success in the written exams for the agrégation in 1929, Sartre requested to be introduced to her. Beauvoir thus joined Sartre and his “comrades” in study sessions to prepare for the grueling public oral examination component of the agrégation. For the first time, she found in Sartre an intellect worthy (and, as she asserted, in some ways superior) to her own-a characterization that has lead to many ungrounded assumptions concerning Beauvoir’s lack of philosophical originality. For the rest of their lives, they were to remain “essential” lovers, while allowing for “contingent” love affairs whenever each desired. Although never marrying (despite Sartre’s proposal in 1931), having children together, or even living in the same home, Sartre and Beauvoir remained intellectual and romantic partners until Sartre’s death in 1980.

The liberal intimate arrangement between her and Sartre was extremely progressive for the time and often unfairly tarnished Beauvoir’s reputation as a woman intellectual equal to her male counterparts. Adding to her unique situation with Sartre, Beauvoir had intimate liaisons with both women and men. Some of her more famous relationships included the journalist Jacques Bost, the American author Nelson Algren, and Claude Lanzmann, the maker of the Holocaust documentary, Shoah.

In 1931, Beauvoir was appointed to teach in a lycée at Marseilles whereas Sartre’s appointment landed him in Le Havre. In 1932, Beauvoir moved to the Lycée Jeanne d’Arc in Rouen where she taught advanced literature and philosophy classes. In Rouen she was officially reprimanded for her overt criticisms of woman’s situation and her pacifism. In 1940, the Nazis occupied Paris and in 1941, Beauvoir was dismissed from her teaching post by the Nazi government. As a result of the effects of World War II on Europe, Beauvoir began exploring the problem of the intellectual’s social and political engagement with his or her time.

Following a parental complaint made against her for corrupting one of her female students, she was dismissed from teaching again in 1943. She was never to return to teaching. Although she loved the classroom environment, Beauvoir had always wanted to be an author from her earliest childhood. Her collection of short stories on women, Quand prime le spirituel (When Things of the Spirit Come First) was rejected for publication and not published until many years later (1979). However, her fictionalized account of the triangular relationship between herself, Sartre and her student, Olga Kosakievicz, L’Invitée (She Came to Stay), was published in 1943. This novel, written from 1935 to 1937 (and read by Sartre in manuscript form as he began writing Being and Nothingness) successfully gained her public recognition.

The Occupation inaugurated what Beauvoir has called the “moral period” of her literary life. From 1941 to 1943 she wrote her novel, Le Sang des Autres (The Blood of Others), which was heralded as one of the most important existential novels of the French Resistance. In 1943 she wrote her first philosophical essay, an ethical treatise entitled Pyrrhus et Cinéas. Finally, this period includes the writing of her novel, Tous Les Hommes sont Mortels (All Men are Mortal), written from 1943-46 and her only play, Les Bouches Inutiles (Who Shall Die?), written in 1944.

Although only cursorily involved in the Resistance, Beauvoir’s political commitments underwent a progressive development in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Together with Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Raymond Aron and other intellectuals, she helped found the politically non-affiliated, leftist journal, Les Temps Modernes in 1945, for which she both edited and contributed articles, including in 1945, “Moral Idealism and Political Realism,” “Existentialism and Popular Wisdom,” and in 1946, “Eye for an Eye.” Also in 1946, Beauvoir wrote an article explaining her method of doing philosophy in literature in “Literature and Metaphysics.” The creation of this journal and her leftist orientation (which was heavily influenced by her reading of Marx and the political ideal represented by Russia), colored her uneasy relationship to Communism. The journal itself and the question of the intellectual’s political commitments would become a major theme of her novel, The Mandarins (1954).

Beauvoir published another ethical treatise, Pour une Morale de l’Ambiguïté (The Ethics of Ambiguity) in 1947. Although she was never fully satisfied with this work, it remains one of the best examples of an existentialist ethics. In 1955, she published, “Must We Burn Sade?” which again approaches the question of ethics from the perspective of the demands of and obligations to the other.

Following advance extracts which appeared in Les Temps Modernes in 1948, Beauvoir published her revolutionary, two-volume investigation into woman’s oppression, Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex) in 1949. Although previous to writing this work she had never considered herself to be a “feminist,” The Second Sex solidified her as a feminist figure for the remainder of her life. By far her most controversial work, this book was embraced by feminists and intellectuals, as well as mercilessly attacked by both the right and the left. The 70’s, famous for being a time of feminist movements, was embraced by Beauvoir who participated in demonstrations, continued to write and lecture on the situation of women, and signed petitions advocating various rights for women. In 1970, Beauvoir helped launch the French Women’s Liberation Movement in signing the Manifesto of the 343 for abortion rights and in 1973, she instituted a feminist section in Les Temps Modernes.

Following the numerous literary successes and the high profile of her and Sartre’s lives, her career was marked by a fame rarely experienced by philosophers during their lifetimes. This fame resulted both from her own work as well as from her relationship to and association with Sartre. For the rest of her life, she lived under the close scrutiny of the public eye. She was often unfairly considered to be a mere disciple of Sartrean philosophy (in part, due to her own proclamations) despite the fact that many of her ideas were original and went in directions radically different than Sartre’s works.

During the 1940’s, she and Sartre, who had at one time relished in the café culture and social life of Paris, found themselves retreating into the safety of their close circle of friends, affectionately named the “Family.” However, her fame did not stop her from continuing her life-long passion of traveling to foreign lands which resulted in two of her works, L’Amérique au Jour le Jour (America Day by Day) first published in 1948 and La Longue Marche (The Long March) published in 1957. The former was written following her lecture tour of the United States in 1947, and the latter following her visit with Sartre to communist China in 1955.

Her later work included the writing of more works of fiction, philosophical essays and interviews. It was notably marked not only by her political action in feminist issues, but also by the publication of her autobiography in four volumes and her political engagement directly attacking the French war in Algeria and the tortures of Algerians by French officers. In 1970, she published an impressive study of the oppression of aged members of society, La Vieillesse (The Coming of Age). This work mirrors the same approach she had taken in The Second Sex only with a different object of investigation.

Beauvoir saw the passing of her lifelong companion in 1980, which is recounted in her 1981 book, La Cérémonie des Adieux (Adieux: A Farewell to Sartre). Following the death of Sartre, Beauvoir officially adopted her companion, Sylvie le Bon, who became her literary executor. Beauvoir died of a pulmonary edema on April 14, 1986.

2. Ethics

a. Pyrrhus et Cineas

For most of her life, Beauvoir was concerned with the ethical responsibility that the individual has to him or herself, other individuals and to oppressed groups. Her early work, Pyrrhus et Cinéas (1944) approaches the question of ethical responsibility from an existentialist framework long before Sartre was to attempt the same endeavor. This essay was well-received as it spoke to a war-torn France that was struggling to find a way out of the darkness of War World II. It begins as a conversation between Pyrrhus, the ancient king of Epirus, and his chief advisor, Cineas, on the question of action. Each time Pyrrhus makes an assertion as to what land he will conquer, Cineas asks him what will he do afterwards? Finally, Pyrrhus exclaims that he will rest following the achievement of all of his plans, to which Cineas retorts, “Why not rest right away”? The essay is thus framed as an investigation into the motives of action and the existential concern with why we should act at all.

This work was written by a young Beauvoir in close dialogue with the Sartre of Being and Nothingness (1943). The framework of an individual freedom engaged in an objective world is close to Sartre’s conception of the conflict between being-for-itself (l’être-pour-soi) and being-in-itself (l’être-en-soi). Differing from Sartre, Beauvoir’s analysis of the free subject immediately implies an ethical consideration of other free subjects in the world. The external world can often manifest itself as a crushing, objective reality whereas the other can reveal to us our fundamental freedom. Lacking a God to guarantee morality, it is up to the individual existent to create a bond with others through ethical action. This bond requires a fundamentally active orientation to the world through projects that express our own freedom as well as encourage the freedom of our fellow human beings. Because to be human is essentially to rupture the given world through our spontaneous transcendence, to be passive is to live, in Sartrean terminology, in bad faith.

Although emphasizing key Sartrean motifs of transcendence, freedom and the situation in this early work, Beauvoir takes her enquiry in a different direction. Like Sartre, she believes that that human subjectivity is essentially a nothingness which ruptures being through spontaneous projects. This movement of rupturing the given through the introduction of spontaneous activity is called transcendence. Beauvoir, like Sartre, believes that the human being is constantly engaged in projects which transcend the factical situation (cultural, historical, personal, etc.) into which the existent is thrown. Yet, even though much of her nomenclature and ideas obviously emerge within a philosophical discourse with Sartre, her goal in writing Pyrrhus et Cinéas is somewhat different than his. Most notably, in Pyrrhus et Cinéas, she constructs an ethics, which is a project postponed by Sartre in Being and Nothingness. In addition, rather than seeing the other (who in his or her gaze turns me into an object) as a threat to my freedom as Sartre would have it, Beauvoir sees the other as the necessary axis of my freedom-without whom, in other words, I could not be free. With the goal of elucidating an existentialist ethics then, Beauvoir is concerned with questions of oppression that are largely absent in Sartre’s early work.

Pyrrhus et Cinéas is a richly philosophical text which incorporates themes not only from Sartre, but also from Hegel, Heidegger, Spinoza, Voltaire, Nietzsche, and Kierkegaard. However, Beauvoir is as critical of these philosophers as she is admiring. For example, she criticizes Hegel for his unethical faith in progress which sublates the individual in the relentless pursuit of the Absolute. She criticizes Heidegger for his emphasis on being-towards-death as undermining the necessity of setting up projects, which are themselves ends and are not necessarily projections towards death.

Beauvoir emphasizes that one’s transcendence is realized through the human project which sets up its own end as valuable, rather than relying on external validation or meaning. The end, therefore, is not something cut off from activity, standing as a static and absolute value outside of the existent who chooses it. Rather, the goal of action is established as an end through the very freedom which posits it as a worthwhile enterprise. Beauvoir maintains the existentialist belief in absolute freedom of choice and the consequent responsibility that such freedom entails, by emphasizing that one’s projects must spring from individual spontaneity and not from an external institution, authority, or person. As such, she is sharply critical of the Hegelian absolute, the Christian conception of God and abstract entities such as Humanity, Country and Science which demand the individual’s renunciation of freedom into a static Cause. All world-views which demand the sacrifice and repudiation of freedom diminish the reality, thickness, and existential importance of the individual existent. This is not to say that we should abandon all projects of unification and scientific advancement in favor of a disinterested solipsism, only that such endeavors must necessarily honor the individual existents of which they are composed. Additionally, instead of being forced into causes of various kinds, existents must actively and self-consciously choose to participate in them.

Because Beauvoir is so concerned in this essay with freedom and the necessity to self-consciously choose who one is at every moment, she takes up relationships of slavery, mastery, tyranny, and devotion which remain choices despite the inequalities that often result from these connections with others. Despite the inequity of power in such relationships, she maintains that we can never do anything for or against others, i.e., we can never act in the place of others because each individual can only be responsible for him or herself. However, we are still morally obligated to keep from harming others. Echoing a common theme in existentialist philosophy, even to be silent or to refuse to engage in helping the other, is still making a choice. Freedom, in other words, cannot be escaped.

Yet, she also develops the idea that in abstaining from encouraging the freedom of others, we are acting against the ethical call of the other. Without others, our actions are destined to fall back upon themselves as useless and absurd. However, with others who are also free, our actions are taken up and carried beyond themselves into the future-transcending the limits of the present and of our finite selves. Our very actions are calls to other freedoms who may choose to respond to or ignore us. Because we are finite and limited and there are no absolutes to which our actions can or should conform, we must carry out our projects in risk and uncertainty. But it is just this fragility that Beauvoir believes opens us up to a genuine possibility for ethics.

b. The Ethics of Ambiguity

In many ways, The Ethics of Ambiguity (1947) continues themes first developed in Pyrrhus et Cinéas. Beauvoir continues to believe in the contingency of existence in that there is no necessity that we exist and thus there is no predetermined human essence or standard of value. Of particular importance, Beauvoir expounds upon the idea that human freedom requires the freedom of others for it to be actualized. Although Beauvoir was never fully satisfied with The Ethics of Ambiguity, it remains a testament to her long-standing concern with freedom, oppression, and responsibility, as well as to the depth of her philosophical understanding of the history of philosophy and of her own unique contributions to it.

She begins this work by asserting the tragic condition of the human situation which experiences its freedom as a spontaneous internal drive that is crushed by the external weight of the world. Human existence, she argues, is always an ambiguous admixture of the internal freedom to transcend the given conditions of the world and the weight of the world which imposes itself on us in a manner outside of our control and not of our own choosing. In order for us to live ethically then, we must assume this ambiguity rather than try to flee it.

In Sartrean terms, she sets up a problem in which each existent wants to deny their paradoxical essence as nothingness by desiring to be in the strict, objective sense; a project that is doomed to failure and bad faith. In many ways, Beauvoir’s task is to describe the existentialist conversion alluded to by Sartre in Being and Nothingness, but postponed until the much later, incomplete attempt in his Cahiers Pour une Morale. For Beauvoir, an existentialist conversion allows us to live authentically at the crossroads of freedom and facticity. This requires that we engage our freedom in projects which emerge from a spontaneous choice. In addition, the ends and goals of our actions must never be set up as absolutes, separate from we who choose them. In this sense, Beauvoir sets limits to freedom. To be free is not to have free license to do whatever one wants. Rather, to be free entails the conscious assumption of this freedom through projects which are chosen at each moment. The meaning of actions is thus granted not from some external source of values (say in God, the church, the state, our family, etc.), but in the existent’s spontaneous act of choosing them. Each individual must positively assume his or her project (whether it be to write a novel, graduate from university, preside over a courtroom, etc.) and not try to escape freedom by escaping into the goal as into a static object. Thus, we act ethically only insofar as we accept the weight of our choices and the consequences and responsibilities of our fundamental, ontological freedom. As Beauvoir tells us, “to will oneself moral and to will oneself free are one and the same decision.”

The genuine human being thus does not recognize any foreign absolute not consciously and actively chosen by the person him or herself. This idea is perhaps best seen in Beauvoir’s critique of Hegel which runs throughout this text. Although Hegel is not the only philosopher with whom she is in dialogue (she addresses Kant, Marx, Descartes, and Sartre, as well) he represents the philosophical crystallization of the desire for human beings to escape their freedom by submerging it into an external absolute. Thus Hegel, for Beauvoir, sets up an “Absolute Subject” whose realization only comes at the end of history, thereby justifying the sacrifice of countless individuals in the relentless pursuit of its own perfection. As such, Hegel’s Absolute represents an abstraction which is taken as the truth of existence which annihilates instead of preserves the individual human lives which compose it. Only a philosophy which values the freedom of each individual existent can alone be ethical. Philosophies such as those of Hegel, Kant, and Marx which privilege the universal are built upon the necessary diminution of the particular and as such, cannot be authentically ethical systems. Beauvoir claims against these philosophers of the absolute, that existentialism embraces the plurality of the concrete, particular human beings enmeshed in their own unique situations and engaged in their own projects.

However, Beauvoir is also emphatic that even though existentialist ethics upholds the sanctity of individuals, an individual is always situated within a community and as such, separate existents are necessarily bound to each other. She argues that every enterprise is expressed in a world populated by and thus affecting other human beings. She defends this position by returning to an idea touched upon in Pyrrhus et Cinéas and more fully developed in the Ethics, which is that individual projects fall in upon themselves if there are not others with whom our projects intersect and who consequently carry our actions beyond us in space and time.

In order to illustrate the complexity of situated freedom, Beauvoir provides us with an important element of growth, development and freedom in The Ethics of Ambiguity. Most philosophers begin their discussions with a fully-grown, rational human being, as if only the adult concerns philosophical inquiry. However, Beauvoir incorporates an analysis of childhood in which she argues that the will, or freedom, is developed over time. Thus, the child is not considered moral because he or she does not have a connection to a past or future and action can only be understood as unfolding over time. In addition, the situation of the child gives us a glimpse into what Beauvoir calls the attitude of seriousness in which values are given, not chosen. In fact, it is because each person was once a child that the serious attitude is the most prevalent form of bad faith.

Describing the various ways in which existents flee their freedom and responsibility, Beauvoir catalogues a number of different inauthentic attitudes, which in various forms are all indicative of a flight from freedom. As the child is neither moral nor immoral, the first actual category of bad faith consists of the “sub-man” who, through boredom and laziness, restrains the original movement of spontaneity in the denial of his or her freedom. This is a dangerous attitude in which to live because even as the sub-man rejects freedom, he or she becomes a useful pawn to be recruited by the “serious man” to enact brutal, immoral and violent action. The serious man is the most common attitude of flight as he or she embodies the desire that all existents share to found their freedom in an objective, external standard. The serious man upholds absolute and unconditioned values to which he or she subordinates his or her freedom. The object into which the serious attitude attempts to merge itself is not important-it can be the Military for the general, Fame for the actress, Power for the politician-what is important is that the self is lost into it. But as Beauvoir has already told us, all action loses meaning if it is not willed from freedom, setting up freedom as its goal. Thus the serious man is the ultimate example of bad faith because rather than seeking to embrace freedom, he or she seeks to lose into an external idol. All existents are tempted to set up values of seriousness (say, for example, by claiming that one is a “republican” or a “liberal” as if these monikers were substantial “things” that defined us in any essential sense) so as to give meaning to their lives. But the attitude of seriousness gives rise to tyranny and oppression when the “Cause” is pronounced more important than those who comprise it.

Other attitudes of bad faith include the “nihilist” which is an attitude resulting from disappointed seriousness turned back on itself. When the general understands that the military is a false idol that does not justify his existence, he may become a nihilist and deny that the world has any meaning at all. The nihilist desires to be nothing which is not unlike the reality of human freedom for Beauvoir. However, the nihilist is not an authentic choice because he or she does not assert nothingness in the sense of freedom, but in the sense of denial. Although mentioning other interesting attitudes of bad faith (such as the “demoniacal man” and the “passionate man”) the last attitude of importance is the attitude of the “adventurer.” The adventurer is interesting because it is so close to an authentically moral attitude. Disdaining the values of seriousness and nihilism, the adventurer throws him or herself into life and chooses action for its own sake. But the adventurer cares only for his or her own freedom and projects, and thus embodies a selfish and potentially tyrannical attitude. The adventurer demonstrates a tendency to align him or herself with whoever will bestow power, pleasure and glory. And often those who bestow such gifts, do not have the welfare of humanity as their main concern.

One of Beauvoir’s greatest achievements in The Ethics of Ambiguity is found in her analyses of situation and mystification. For the early Sartre, one’s situation (or facticity) is merely that which is to be transcended in the spontaneous surge of freedom. The situation is certainly a limit, but it is a limit-to-be-surpassed. Beauvoir, however, recognizes that some situations are such that they cannot be simply transcended but serve as strict and almost unsurpassable inhibitors to action. For example, she tells us that there are oppressed peoples such as slaves and many women who exist in a childlike world in which values, customs, gods, and laws are given to them without being freely chosen. Their situation is defined not by the possibility of transcendence, but by the enforcement of external institutions and power structures. Because of the power exerted upon them, their limitations cannot, in many circumstances, be transcended because they are not even known. Their situation, in other words, appears to be the natural order of the world. Thus the slave and the woman are mystified into believing that their lot is assigned to them by nature. As Beauvoir explains, because we cannot revolt against nature, the oppressor convinces the oppressed that their situation is what it is because they are naturally inferior or slavish. In this way, the oppressor mystifies the oppressed by keeping them ignorant of their freedom, thereby preventing them from revolting. Beauvoir rightly points out that one simply cannot claim that those who are mystified or oppressed are living in bad faith. We can only judge the actions of those individuals as emerging from their situation.

Only the authentically moral attitude understands that the freedom of the self requires the freedom of others. To act alone or without concern for others is not to be free. As Beauvoir explains, “No project can be defined except by its interference with other projects.” Thus if my project intersects with others who are enslaved-either literally or through mystification-I too am not truly free. What is more, if I do not actively seek to help those who are not free, I am implicated in their oppression.

As this book was written after World War II, it is not so surprising that Beauvoir would be concerned with questions of oppression and liberation and the ethical responsibility that each of us has to each other. Clearly she finds the attitude of seriousness to be the leading culprit in nationalistic movements such as Nazism which manipulate people into believing in a Cause as an absolute and unquestionable command, demanding the sacrifice of countless individuals. Beauvoir pleads with us to remember that we can never prefer a Cause to a human being and that the end does not necessarily justify the means. In this sense, Beauvoir is able to promote an existential ethics which asserts the reality of individual projects and sacrifice while maintaining that such projects and sacrifices have meaning only in a community comprised of individuals with a past, present, and future.

3. Feminism

a. The Second Sex

Most philosophers agree that Beauvoir’s greatest contribution to philosophy is her revolutionary magnum opus, The Second Sex. Published in two volumes in 1949 (condensed into one text divided into two “books” in English), this work immediately found both an eager audience and harsh critics. The Second Sex was so controversial that the Vatican put it (along with her novel, The Mandarins) on the Index of prohibited books. At the time The Second Sex was written, very little serious philosophy on women from a feminist perspective had been done. With the exception of a handful of books, systematic treatments of the oppression of women both historically and in the modern age were almost unheard of. Striking for the breadth of research and the profundity of its central insights, The Second Sex remains to this day one of the foundational texts in philosophy, feminism, and women’s studies.

The main thesis of The Second Sex revolves around the idea that woman has been held in a relationship of long-standing oppression to man through her relegation to being man’s “Other.” In agreement with Hegelian and Sartrean philosophy, Beauvoir finds that the self needs otherness in order to define itself as a subject; the category of the otherness, therefore, is necessary in the constitution of the self as a self. However, the movement of self-understanding through alterity is supposed to be reciprocal in that the self is often just as much objectified by its other as the self objectifies it. What Beauvoir discovers in her multifaceted investigation into woman’s situation, is that woman is consistently defined as the Other by man who takes on the role of the Self. As Beauvoir explains in her Introduction, woman “is the incidental, the inessential, as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute-she is the Other.” In addition, Beauvoir maintains that human existence is an ambiguous interplay between transcendence and immanence, yet men have been privileged with expressing transcendence through projects, whereas women have been forced into the repetitive and uncreative life of immanence. Beauvoir thus proposes to investigate how this radically unequal relationship emerged as well as what structures, attitudes and presuppositions continue to maintain its social power.

The work is divided into two major themes. The first book investigates the “Facts and Myths” about women from multiple perspectives including the biological-scientific, psychoanalytic, materialistic, historical, literary and anthropological. In each of these treatments, Beauvoir is careful to claim that none of them is sufficient to explain woman’s definition as man’s Other or her consequent oppression. However, each of them contributes to woman’s overall situation as the Other sex. For example, in her discussion of biology and history, she notes the women experience certain phenomena such as pregnancy, lactation, and menstruation that are foreign to men’s experience and thus contribute to a marked difference in women’s situation. However, these physiological occurrences in no way directly cause woman to be man’s subordinate because biology and history are not mere “facts” of an unbiased observer, but are always incorporated into and interpreted from a situation. In addition, she acknowledges that psychoanalysis and historical materialism contribute tremendous insights into the sexual, familial and material life of woman, but fail to account for the whole picture. In the case of psychoanalysis, it denies the reality of choice and in the case of historical materialism, it neglects to take into account the existential importance of the phenomena it reduces to material conditions.

The most philosophically rich discussion of Book I comes in Beauvoir’s analysis of myths. There she tackles the way in which the preceding analyses (biological, historical, psychoanalytic, etc.) contribute to the formulation of the myth of the “Eternal Feminine.” This paradigmatic myth, which incorporates multiple myths of woman under it (such as the myth of the mother, the virgin, the motherland, nature, etc.) attempts to trap woman into an impossible ideal by denying the individuality and situation of all different kinds of women. In fact, the ideal set by the Eternal Feminine sets up an impossible expectation because the various manifestations of the myth of femininity appear as contradictory and doubled. For example, history shows us that for as many representations of the mother as the respected guardian of life, there are as many depictions of her as the hated harbinger of death. The contradiction that man feels at having been born and having to die gets projected onto the mother who takes the blame for both. Thus woman as mother is both hated and loved and individual mothers are hopelessly caught in the contradiction. This doubled and contradictory operation appears in all feminine myths, thus forcing women to unfairly take the burden and blame for existence.

Book II begins with Beauvoir’s most famous assertion, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” By this, Beauvoir means to destroy the essentialism which claims that women are born “feminine” (according to whatever the culture and time define it to be) but are rather constructed to be such through social indoctrination. Using a wide array of accounts and observations, the first section of Book II traces the education of woman from her childhood, through her adolescence and finally to her experiences of lesbianism and sexual initiation (if she has any). At each stage, Beauvoir illustrates how women are forced to relinquish their claims to transcendence and authentic subjectivity by a progressively more stringent acceptance of the “passive” and “alienated” role to man’s “active” and “subjective” demands. Woman’s passivity and alienation are then explored in what Beauvoir entitles her “Situation” and her “Justifications.” Beauvoir studies the roles of wife, mother, and prostitute to show how women, instead of transcending through work and creativity, are forced into monotonous existences of having children, tending house and being the sexual receptacles of the male libido.

Because she maintains the existentialist belief in the absolute ontological freedom of each existent regardless of sex, Beauvoir never claims that man has succeeded in destroying woman’s freedom or in actually turning her into an “object” in relation to his subjectivity. She remains a transcendent freedom despite her objectification, alienation and oppression.

Although we certainly can not claim that woman’s role as the Other is her fault, we also cannot say that she is always entirely innocent in her subjection. As taken up in the discussion of The Ethics of Ambiguity, Beauvoir believes that there are many possible attitudes of bad faith where the existent flees his or her responsibility into prefabricated values and beliefs. Many women living in a patriarchal culture are guilty of the same action and thus are in some ways complicitous in their own subjugation because of the seeming benefits it can bring as well as the respite from responsibility it promises. Beauvoir discusses three particular inauthentic attitudes in which women hide their freedom in: “The Narcissist,” “The Woman in Love,” and “The Mystic.” In all three of these attitudes, women deny the original thrust of their freedom by submerging it into the object; in the case of the first, the object is herself, the second, her beloved and the third, the absolute or God.

Beauvoir concludes her work by asserting various concrete demands necessary for woman’s emancipation and the reclamation of her selfhood. First and foremost, she demands that woman be allowed to transcend through her own free projects with all the danger, risk, and uncertainty that entails. As such, modern woman “prides herself on thinking, taking action, working, creating, on the same terms as men; instead of seeking to disparage them, she declares herself their equal.” In order to ensure woman’s equality, Beauvoir advocates such changes in social structures such as universal childcare, equal education, contraception, and legal abortion for women-and perhaps most importantly, woman’s economic freedom and independence from man. In order to achieve this kind of independence, Beauvoir believes that women will benefit from non-alienating, non-exploitative productive labor to some degree. In other words, Beauvoir believes that women will benefit tremendously from work. As far as marriage is concerned, the nuclear family is damaging to both partners, especially the woman. Marriage, like any other authentic choice, must be chosen actively and at all times or else it is a flight from freedom into a static institution.

Beauvoir’s emphasis on the fact that women need access to the same kinds of activities and projects as men places her to some extent in the tradition of liberal, or second-wave feminism. She demands that women be treated as equal to men and laws, customs and education must be altered to encourage this. However, The Second Sex always maintains its fundamental existentialist belief that each individual, regardless of sex, class or age, should be encouraged to define him or herself and to take on the individual responsibility that comes with freedom. This requires not just focusing on universal institutions, but on the situated individual existent struggling within the ambiguity of existence.

4. Literature

a. Novels

In her autobiographies, Beauvoir often makes the claim that although her passion for philosophy was lifelong, her heart was always set on becoming an author of great literature. What she succeeded in doing was writing some of the best existentialist literature of the 20th century. Much as Camus and Sartre discovered, existentialism’s concern for the individual thrown into an absurd world and forced to act, lends itself well to the artistic medium of fiction. All of Beauvoir’s novels incorporate existential themes, problems, and questions in her attempt to describe the human situation in times of personal turmoil, political upheaval, and social unrest.

Her first novel, L’Invitée (She Came to Stay) was published in 1943. Opening with a quote from Hegel about the desire of self-consciousness to seek the death of the other, the book is a complex psychological study of the battles waged for selfhood. Set during the buildup to World War II, it charts the complexity of war in individual relationships. The protagonist, Françoise is forced to undergo the realization that she is not the center of the world and that her relationship to her lover, Pierre is not guaranteed but must, like all relationships, be constantly chosen and won. This work brought her recognition and lead to the writing of one of her most critically acclaimed novels, Le Sang des Autres (The Blood of Others) in 1945. This work begins to take into account the social responsibility that one’s times demand. Set during the German Occupation of France, it follows the lives of the Patriot leader, Jean Blomart and his agony over sending his lover to her death. This work was heralded as one of the leading existential novels of the Resistance and stands as a testimony to the often tragic contradiction between the responsibility we have to ourselves, to those we love, and to our people and humanity as a whole.

In 1946, Beauvoir published Tous les Hommes sont Mortels (All Men are Mortal) which revolves around the question of mortality and immortality. When an aspiring actress discovers that a mysterious and morose man is immortal, she becomes obsessed with her own immortality which she believes will be carried forth by him into eternity after her death. Although this work was not as well-received by critics and the public, it is especially provocative with the phenomena of time and mortality and the desire all human beings share to achieve immortality in any form we can, and how this leads to a denial of lived experience in the here and now.

Les Mandarins (The Mandarins), Beauvoir’s most famous and critically acclaimed novel was published in 1954 and soon thereafter won the prestigious French award for literature, the Prix Goncourt. This work is a profound study of the responsibilities that the intellectual has to his or her society. It explores the virtues and pitfalls of philosophy, journalism, theater, and literature as these media try to speak to their age and to implement social change. The Mandarins brings in a number of Beauvoir’s own personal concerns as it tarries with the issues of Communism and Socialism, the fears of American imperialism and the nuclear bomb, and the relationship of the individual intellectual to other individuals and to society. It also raises the questions of personal and political allegiance and how the two often conflict with tragic results. Finally, Beauvoir’s novel, Les Belles Images (1966), explores the constellation of relationships, hypocrisy and social mores in Parisian society.

b. Short Stories

Beauvoir wrote two collections of short stories. The first, Quand Prime le Spirituel (When Things of the Spirit Come First) wasn’t published until 1979 even though it was her first work of fiction submitted (and rejected) for publication (in 1937). As the 1930’s were less amenable to both women writers and stories on women, it is not so peculiar that this collection was rejected only to be rediscovered and esteemed over forty years later. This work offers fascinating insight into Beauvoir’s concerns with women and their unique attitudes and situations long before the writing of The Second Sex. Divided into five chapters, each titled by the name of the main female character, it exposes the hypocrisy of the French upper classes who hide their self-interests behind a veil of intellectual or religious absolutes. The stories take up the issues of the crushing demands of religious piety and individual renunciation, the tendency to aggrandize our lives to others and the crisis of identity when we are forced to confront our deceptions, and the difficulty of being a woman submitted to bourgeois and religious education and expectations. Beauvoir’s second collection of short stories, La Femme Rompue (The Woman Destroyed), was published in 1967 and was considerably well-received. This too offers separate studies of three women, each of whom is living in bad faith in one form or another. As each encounters a crisis in her familial relationships, she engages in a flight from her responsibility and freedom. This collection expands upon themes found in her ethics and feminism of the often denied complicity in one’s own undoing.

c. Theater

Beauvoir only wrote one play, Les Bouches Inutiles (Who Shall Die?) which was performed in 1945-the same year of the founding of Les Temps Modernes. Clearly enmeshed in the issues of World War II Europe, the dilemma of this play focuses on who is worth sacrificing for the benefit of the collective. This piece was influenced by the history of 14th century Italian towns that, when under siege and facing mass starvation, threw out the old, sick, weak, women and children to fend for themselves so that there might be enough for the strong men to hold out a little longer. The play is set in just such circumstances which were hauntingly resonant to Nazi occupied France. True to Beauvoir’s ethical commitments which assert the freedom and sanctity of the individual only within the freedom and respect of his or her community, the town decides to rise up together and either defeat the enemy or to die together. Although the play contains a number of important and well-developed existential, ethical and feminist themes, it was not as successful as her other literary expressions. Although she never again wrote for the theater, many of the characters of her novels (for example in She Came to Stay, All Men are Mortal, and The Mandarins) are playwrights and actors, showing her confidence in the theatrical arts to convey crucial existential and socio-political dilemmas.

5. Cultural Studies

a. Travel Observations

Beauvoir was always passionate about traveling and embarked upon many adventures both alone and with Sartre and others. Two trips had a tremendous impact upon her and were the impetus for two major books. The first, L’Amérique au Jour le Jour (America Day by Day) was published in 1948, the year after her lecture tour of the United States in 1947. During this visit, she spent time with Richard and Ellen Wright, met Nelson Algren, and visited numerous American cities such as New York, Chicago, Hollywood, Las Vegas, New Orleans and San Antonio. During her stay, she was commissioned by the New York Times to write an article entitled, “An Existentialist Looks at Americans,” appearing on May 25, 1947. It offers a penetrating critique of the United States as a country so full of promise but also one that is a slave to novelty, material culture, and a pathological fixation on the present at the expense of the past. Such themes are repeated in greater detail in America Day by Day, which also tackles the issue of America’s strained race relations, imperialism, anti-intellectualism, and class tensions.

The second major work to come out of Beauvoir’s travels resulted from her two-month trip to China with Sartre in 1955. Published in 1957, La Longue Marche (The Long March) is a generally positive account of the vast Communist country. Although disturbed by the censorship and careful choreographing of their visit by the Communists, she found China to be working towards a betterment in the life of its people. The themes of labor and the plight of the worker are common throughout this work, as is the situation of women and the family. Despite the breadth of its investigation and the desire on Beauvoir’s behalf to study a completely foreign culture, it was both a critical and a personal embarrassment. She later admitted that it was done more to make money than to offer a serious cultural analysis of China and its people. Regardless of these somewhat justified criticisms, it stands as interesting exploration of the tension between capitalism and Communism, the self and its other, and what it means to be free in different cultural contexts.

b. The Coming of Age

In 1967, Beauvoir began a monumental study of the same genre and caliber as The Second Sex. La Vieillesse (The Coming of Age, 1970) met with instant critical success. The Second Sex had been received with considerable hostility from many groups who did not want to be confronted with an unpleasant critique of their sexist and oppressive attitudes towards women; The Coming of Age however, was generally welcomed although it too critiques society’s prejudices towards another oppressed group: the elderly. This masterful work takes the fear of age as a cultural phenomenon and seeks to give voice to a silenced and detested class of human beings. Lashing out against the injustices suffered by the old, Beauvoir successfully complicates a problem all too oversimplified. For example, she notes that, depending on one’s work or class, old age can come earlier or later. Those who are materially more advantaged can afford good medicine, food and exercise, and thus live much longer and age less quickly, than a miner who is old at 50. In addition, she notices the philosophically complex connection between age and poverty and age and dehumanization.

As she had done in with The Second Sex, Beauvoir approaches the subject matter of The Coming of Age from a variety of perspectives including the biological, anthropological, historical, and sociological. In addition, she explores the question of age from the perspective of the living, elderly human being in relation to his or her body, time and the external world. Just as with The Second Sex, this later work is divided into two books, the first which deals with “Old Age as Seen from Without” and the second with, “Being-in-the-World.” Beauvoir explains the motivation for this division in her Introduction where she writes, “Every human situation can be viewed from without-seen from the point of view of an outsider-or from within, in so far as the subject assumes and at the same time transcends it.” Continuing to uphold her belief in the fundamental ambiguity of existence which always sits atop the contradiction of immanence and transcendence, objectivity and subjectivity, Beauvoir treats the subject of age both as an object of cultural-historical knowledge and as the first-hand, lived experience of aged individuals.

What she concludes from her investigation into the experience, fear and stigma of old age is that even though the process of aging and the decline into death is an inescapable, existential phenomenon for those human beings who live long enough to experience it, there is no necessity to our loathing the aged members of society. There is a certain acceptance of the fear of age felt by most people because it ironically stands as more of the opposite to life than does death. However, this does not demand that the aged merely resign themselves to waiting for death or for younger members of society to treat them as the invisible class. Rather, Beauvoir argues in true existentialist fashion that old age must still be a time of creative and meaningful projects and relationships with others. This means that above all else, old age must not be a time of boredom, but a time of continuous political and social action. This requires a change of orientation among the aged themselves and within society as a whole which must transform its idea that a person is only valuable insofar as they are profitable. Instead, both individuals and society must recognize that a person’s value lies in his or her humanity which is unaffected by age.

c. Autobiographical Works

In her autobiography, Beauvoir tells us that in wanting to write about herself she had to first explain what it meant to be a woman and that this realization was the genesis of The Second Sex. However, Beauvoir also successfully embarked upon the recounting of her life in four volumes of detailed and philosophically rich autobiography. In addition to painting a vibrant picture of her own life, Beauvoir also gives us access into other influential figures of the 20th century ranging from Camus, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty, to Richard Wright, Jean Cocteau, Jean Genet, Antonin Artaud and Fidel Castro among many others. Even though her autobiography covers both non-philosophical and philosophical ground, it is important not to downplay the role that autobiography has in Beauvoir’s theoretical development. Indeed, many other existentialists, such as Nietzsche, Sartre, and Kierkegaard, embrace the autobiographical as a key component to the philosophical. Beauvoir always maintained the importance of the individual’s situation and experience in the face of contingency and the ambiguity of existence. Through the recounting of her life, we are given a unique and personal picture of Beauvoir’s struggles as a philosopher, social reformer, writer and woman during a time of great cultural and artistic achievement and political upheaval.

The first volume of her autobiography, Mémoirs d’une Jeune Fille Rangée (Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, 1958), traces Beauvoir’s childhood, her relationship with her parents, her profound friendship with Zaza and her schooling up through her years at the Sorbonne. In this volume, Beauvoir shows the development of her intellectual and independent personality and the influences which lead to her decisions to become a philosopher and a writer. It also presents a picture of a woman who was critical of her class and its expectations of women from an early age. The second volume of her autobiography, La Force de l’Âge (The Prime of Life, 1960) is often considered to be the richest of all the volumes. Like Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, it was commercially and critically well received. Taking up the years from 1929-1944, Beauvoir portrays her transition from student to adult and the discovery of personal responsibility in war and peace. In many points, she explores the motivations for many of her works, such as The Second Sex and The Mandarins. The third installment of her autobiography, La Force des Choses (The Force of Circumstance, 1963; published in two separate volumes) takes up the time frame following the conclusion of World War II in1944 to the year 1962. In these volumes, Beauvoir becomes increasingly more aware of the political responsibility of the intellectual to his or her country and times. In the volume between 1944-1952 (After the War) Beauvoir describes the intellectual blossoming of post-war Paris, rich with anecdotes on writers, filmmakers and artists. The volume focusing on the decade between 1952-1962 (Hard Times), shows a much more subdued and somewhat cynical Beauvoir who is coming to terms with fame, age and the political atrocities waged by France in its war with Algeria (taken up in her work with Gisèle Halimi and the case of Djamila Boupacha). Because of its brutal honesty on the themes of aging, death and war, this volume of her autobiography was less well-received than the previous two. The final installment in the chronicling of her life charts the years from 1962-1972. Tout Compte Fait, (All Said and Done, 1972) shows an older and wiser philosopher and feminist who looks back over her life, her relationships, and her accomplishments and recognizes that it was all for the best. Here Beauvoir shows her commitments to feminism and social change in a clarity only hinted at in earlier volumes and she continues to struggle with the virtues and pitfalls of capitalism and Communism. Additionally, she returns to past works such as The Second Sex, to reevaluate her motivations and her conclusions about literature, philosophy, and the act of remembering. She again returns to the themes of death and dying and their existential significance as she begins to experience the passing of those she loves.

Although not exactly considered to be “autobiography,” it is worth mentioning two more facets of Beauvoir’s self-revelatory literature. The first consists of her works on the lives and deaths of loved ones. In this area, we find her sensitive and personal recounting of her mother’s death in Une Mort très Douce (A Very Easy Death, 1964). This book is often considered to be one of Beauvoir’s best in its day-by-day portrayal of the ambiguity of love and the experience of loss. In 1981, following the death of Sartre the previous year, she published La Cérémonie des Adieux (Adieux: A Farewell to Sartre) which recounts the progression of an aged and infirm Sartre to his death. This work was somewhat controversial as many readers missed its qualities as a tribute to the late, great philosopher and instead considered it to be an inappropriate exposé on his illness.

The second facet of Beauvoir’s life that can be considered autobiographical are the publication by Beauvoir of Sartre’s letters to her in Lettres au Castor et à Quelques Autres (Letters to Castor and Others, 1983) and of her own correspondence with Sartre in Letters to Sartre published after her death in 1990. Finally, A Transatlantic Love Affair, compiled by Sylvie le Bon de Beauvoir in 1997 and published in 1998, presents Beauvoir’s letters (originally written in English) to Nelson Algren. Each of these works provides us with another perspective into the life of one of the most powerful philosophers of the 20th century and one of the most influential female intellectuals on the history of Western thinking.

6. References and Further Reading

a. Selected Works by Beauvoir (in French and English)

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Adieux: A Farewell to Sartre. Translated by Patrick O’Brian. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986. English translation of La cérémonie des adieux (Paris: Gallimard, 1981).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. All Men are Mortal. Translated by Leonard M. Friedman. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1992. English translation of Tous les Hommes sont Mortels (Paris: Gallimard, 1946).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. All Said and Done. Translated by Patrick O’Brian. New York: Paragon House, 1993. English translation of Tout compte fait (Paris: Gallimard, 1972).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. America Day by Day. Translated by Carol Cosman. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. English translation of L’Amérique au jour le jour (Paris: Gallimard, 1954).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Sons & Co. Ltd., 1968. English translation of Les belles images (Paris: Gallimard, 1966).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Blood of Others. Translated by Roger Senhouse and Yvonne Moyse. New York: Pantheon Books, 1948. English translation of Le sang des autres (Paris: Gallimard, 1945).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Coming of Age. Translated by Patrick O’Brian. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996. English translation of La vieillesse (Paris: Gallimard, 1970).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. “In Defense of Djamila Boupacha.” Le Monde, 3 June, 1960. Appendix B in Djamila Boupacha: The Story of the Torture of a Young Algerian Girl which Shocked Liberal French Opinion; Introduction to Djamila Boupacha. Edited by Simone de Beauvoir and Gisèle Halimi. Translated by Peter Green. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1962. English translations of Djamila Boupacha (Paris: Gallimard, 1962).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Ethics of Ambiguity. Translated by Bernard Frechtman. New York: Citadel Press, 1996. English translation of Pour une morale de l’ambiguïté (Paris: Gallimard, 1947). Beauvoir, Simone de Beauvoir, Simone de. Force of Circumstance, Vol. I: After the War, 1944-1952; Vol. 2: Hard Times, 1952-1962. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Paragon House, 1992. English translation of La force des choses (Paris: Gallimard, 1963).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Letters to Sartre. Translated and Edited by Quintin Hoare. London: Vintage, 1992. English translation of Lettres à Sartre (Paris: Gallimard, 1990).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Long March. Translated by Austryn Wainhouse. New York: The World Publishing, 1958. English translation of La longue marche (Paris: Gallimard, 1957).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Mandarins. Translated by Leonard M. Friedman. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1991. English translation of Les mandarins (Paris: Gallimard, 1954).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter. Translated by James Kirkup. Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1963. English translation of Mémoires d’une jeune fille rangée (Paris: Gallimard, 1958).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Prime of Life. Translated by Peter Green. New York: Lancer Books, 1966. English translation of La force de l’âge (Paris: Gallimard, 1960).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Pyrrhus et Cinéas. Paris: Gallimard, 1944.

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Translated by H. M. Parshley. New York: Vintage Books, 1989. English translation of Le deuxième sexe (Paris: Gallimard, 1949).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Must We Burn Sade? Translated by Annette Michelson, The Marquis de Sade. New York: Grove Press, 1966. English translation of Faut-il brûler Sade? (Paris: Gallimard, 1955).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. She Came to Stay. Translated by Roger Senhouse and Yvonne Moyse. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.,1954. English translation of L’Invitée (Paris: Gallimard, 1943).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. A Transatlantic Love Affair: Letters to Nelson Algren. Compiled and annotated by Sylvie le Bon de Beauvoir. New York: The New Press, 1998.

- Beauvoir, Simone de. A Very Easy Death. Translated by Patrick O’Brian. New York: Pantheon Books, 1965. English translation of Une mort très douce (Paris: Gallimard, 1964).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. When Things of the Spirit Come First. Translated by Patrick O’Brian. New York: Pantheon Books, 1982. English translation of Quand prime le spirituel (Paris: Gallimard, 1979).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Who Shall Die? Translated by Claude Francis and Fernande Gontier. Florissant: River Press, 1983. English translation of Les bouches inutiles (Paris: Gallimard, 1945).

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Woman Destroyed. Translated by Patrick O’Brian. New York: Pantheon Books, 1969. English translation of La femme rompue (Paris: Gallimard, 1967).

b. Selected Books on Beauvoir in English

- Arp, Kristana. The Bonds of Freedom. Chicago: Open Court Publishing, 2001.

- Bair, Deirdre. Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography. New York: Summit Books, 1990.

- Bauer, Nancy. Simone de Beauvoir, Philosophy and Feminism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

- Bergoffen, Debra. The Philosophy of Simone de Beauvoir: Gendered Phenomenologies, Erotic Generosities. Albany: SUNY Press, 1997.

- Fallaize, Elizabeth. The Novels of Simone de Beauvoir. London: Routledge, 1988.

- Fullbrook, Kate and Edward. Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre: The Remaking of a Twentieth-Century Legend. New York: Basic Books: 1994.

- Le Doeuff, Michèle. Hipparchia’s Choice: An Essay Concerning Women, Philosophy, Etc. Translated by Trista Selous. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1991.

- Lundgren-Gothlin, Eva. Sex and Existence: Simone de Beauvoir’s ‘The Second Sex.’ Translated by Linda Schenck. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1996.

- Moi, Toril. Feminist Theory and Simone de Beauvoir. Oxford: Blackwell, 1990.

- Moi, Toril. Simone de Beauvoir: The Making of an Intellectual Woman. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994.

- Okely, Judith. Simone de Beauvoir. New York: Pantheon Books, 1986.

- Scholz, Sally J. On de Beauvoir. Belmont: Wadsworth, 2000.

- Schwarzer, Alice. After the Second Sex: Conversations with Simone de Beauvoir. Translated by Marianne Howarth. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984.

- Simons, Margaret. Beauvoir and the Second Sex: Feminism, Race and the Origins of Existentialism. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999.

- Simons, Margaret. ed. Feminist Interpretations of Simone de Beauvoir. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995.

- Vintges, Karen. Philosophy as Passion: The Thinking of Simone de Beauvoir. Translated by Anne Lavelle. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996.

Author Information

Shannon Mussett

Email: shannon.mussett@uvu.edu

Utah Valley University

U. S. A.