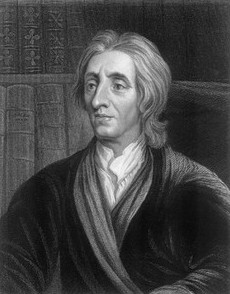

Locke: Epistemology

John Locke (1632-1704), one of the founders of British Empiricism, is famous for insisting that all our ideas come from experience and for emphasizing the need for empirical evidence. He develops his empiricist epistemology in An Essay Concerning Human understanding, which greatly influenced later empiricists such as George Berkeley and David Hume. In this article, Locke’s Essay is used to explain his criticism of innate knowledge and to explain his empiricist epistemology.

John Locke (1632-1704), one of the founders of British Empiricism, is famous for insisting that all our ideas come from experience and for emphasizing the need for empirical evidence. He develops his empiricist epistemology in An Essay Concerning Human understanding, which greatly influenced later empiricists such as George Berkeley and David Hume. In this article, Locke’s Essay is used to explain his criticism of innate knowledge and to explain his empiricist epistemology.

The great divide in Early Modern epistemology is rationalism versus empiricism. The Continental Rationalists believe that we are born with innate ideas or innate knowledge, and they emphasize what we can know through reasoning. By contrast, Locke and other British Empiricists believe that all of our ideas come from experience, and they are more skeptical about what reason can tell us about the world; instead, they think we must rely on experience and empirical observation.

Locke’s empiricism can be seen as a step forward in the development of the modern scientific worldview. Modern science bases its conclusions on empirical observation and always remains open to rejecting or revising a scientific theory based on further observations. Locke would have us do the same. He argues that the only way of learning about the natural world is to rely on experience and, further, that any general conclusions we draw from our limited observations will be uncertain. Although this is commonly understood now, this was not obvious to Locke’s contemporaries. As an enthusiastic supporter of the scientific revolution, Locke and his empiricist epistemology can be seen as part of the same broader movement toward relying on empirical evidence.

Locke’s religious epistemology is also paradigmatic of the ideals of the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment is known as the Age of Reason because of the emphasis on reason and evidence. Locke insists that even religious beliefs should be based on evidence, and he tries to show how religious belief can be supported by evidence. In this way, Locke defends an Enlightenment ideal of rational religion.

The overriding theme of Locke’s epistemology is the need for evidence, and particularly empirical evidence. This article explains Locke’s criticism of innate knowledge and shows how he thinks we can acquire all our knowledge from reasoning and experience.

Table of Contents

- Criticism of Innate Ideas and Knowledge

- Empiricist Account of Knowledge

- Judgment (Rational Belief)

- Conclusion

- References and Further Reading

1. Criticism of Innate Ideas and Knowledge

Many philosophers, including the continental rationalists, have thought that we are born with innate ideas and innate knowledge. Locke criticizes the arguments for innate ideas and knowledge, arguing that any innate ideas or knowledge would be universal but it is obvious from experience that not everyone has these ideas or knowledge. He also offers an alternative explanation, consistent with his empiricism, for how we come to have all our ideas and knowledge. So, he thinks, rationalists fail to prove that we have innate ideas or knowledge.

a. No Innate Ideas

Although Locke holds that all ideas come from experience, many of his contemporaries did not agree.

For example, in the Third Meditation, Descartes argues that the idea of an infinite and perfect God is innate. He argues that we cannot get the idea of an infinite God from our limited experience, and the only possible explanation for how we came to have this idea is that God created us so that we have the innate idea of God already in our minds. Other rationalists make similar arguments for other ideas. Following Noam Chomsky, this is sometimes called a Poverty of Stimulus Argument.

Locke has two responses to the Poverty of Stimulus Arguments for innate ideas. First, Locke argues that some people do not even have the ideas that the rationalists claim are innate. For example, some cultures have never heard of the theistic conception of God and so have never formed this kind of idea of God (1.4.8). In reply, some might claim that the idea of God is in the mind even if we are not conscious of that idea. For example, Plato suggests we are born with the idea of equality but we become conscious of this idea only after seeing equal things and thus “recollect” the idea; Leibniz suggests innate ideas are “petite perceptions” that are present even though we do not notice them. However, Locke argues that saying an idea is “in the mind” when we are not aware of it is unintelligible. An idea is whatever we are aware of, and so if we are not aware of an idea, then it is not “in the mind” at all (1.2.5).

Second, the Poverty of Stimulus Argument claims that certain ideas cannot come from experience, but Locke explains how a wide variety of our ideas do come from experience. For example, in response to Descartes’ claim that the idea of God cannot come from experience, Locke explains how the idea of God can be derived from experience. First, we get the idea of knowledge and power, and so forth, by reflecting on ourselves (2.1.4). Second, we can take the idea of having some power and imagine a being that has all power, and we can take the idea of some knowledge and imagine a being that has all knowledge (2.23.33). In this way, we can use our ideas from experience to form an idea of an infinitely powerful and omniscient God. Since he can explain how we got the idea of God from experience, there is little reason to believe Descartes’ claim that the idea of God is innate.

b. Empiricist Theory of Ideas

Locke’s criticism of innate ideas would be incomplete without an alternative explanation for how we get the ideas we have, including the ideas that the rationalists claim are innate. This section, then, describes how Locke thinks we form ideas.

Locke famously says the mind is like a blank piece of paper and that it has ideas only by experience (Essay 2.1.2). There are two kinds of experience: sensation and reflection. Sensation is sense perception of the qualities of external objects. It is by sensation that we receive ideas such as red, cold, hot, sweet, and other “sensible qualities” (2.1.3). Reflection is the perception of “the internal operations of our minds” (2.1.2). Consider, for example, the experience of making a decision. We weigh the pros and cons and then decide to do x instead of y. Making the decision is an act of the mind. But notice that there is something it feels like to deliberate about the options and then decide what to do. That is what Locke means by reflection: it is the experience we have when we notice what is going on in our own minds. By reflection we come to have the ideas of “perception, thinking, doubting, believing, reasoning, knowing, willing, and all the different actings of our own minds” (2.1.4).

The central tenet of Locke’s empiricism is that all of our ideas come from one of these two sources. For many of our ideas, it is obvious how we got them from experience: we got the idea of red from seeing something red, the idea of sweet by tasting something sweet, and so on. But it is less obvious how other ideas come from experience. We can form some new ideas without ever seeing such an object in sense perception, such as the idea of a unicorn or the idea of a gold mountain. Other abstract concepts, such as the idea of justice, seem like something we cannot observe. For Locke’s empiricism to be plausible, then, he needs to explain how we derived these kinds of ideas from experience

Locke divides ideas into simple ideas and complex ideas. A simple idea has “one uniform appearance” and “enter[s] by the senses simple and unmixed” (2.2.1), whereas a complex idea is made up of several simple ideas combined together (2.12.1). For example, snow is both white and cold. The color of the snow has one uniform appearance (i.e., appearing white), and so white is one simple idea that is included in the complex idea of snow. The coldness of snow is another simple idea included in the idea of snow. The idea of snow is a complex idea, then, because it includes several simple ideas.

Locke claims that all simple ideas come from experience (2.2.2), but we can combine simple ideas in new ways. Having already gained from experience the idea of gold and the idea of a mountain, we can combine these together to form the idea of a gold-mountain. This idea depends on our past experience, but we can form the idea of a gold-mountain without ever seeing one. According to Locke’s empiricist theory of ideas, then, all of our complex ideas are combinations of simple ideas we gained from experience (2.12.2).

Abstract ideas also depend on experience. Consider first the abstract idea of white. We form the idea of white by observing several white things: we see that milk, chalk, and snow all have the same sensible quality and call that “white” (2.11.9). We form the idea of white by separating the ideas specific to milk (for example, being a liquid, having a certain flavor), or specific to snow (for example, being cold and fluffy), and attending only to what is the same: namely, being white. We can do the same process of abstraction for complex ideas. For example, we can see a blue triangle, a red triangle, and so on. By focusing on what is the same (having three straight sides) and setting aside what is different (for example, the color, the angles) we can form an abstract idea of triangle.

The Poverty of Stimulus argument for innate ideas claims that some of our ideas cannot come from experience and hence they are innate. However, Locke tries to explain how all of our ideas are derived, directly or indirectly, from experience. All simple ideas come from sensation or reflection, and we can then form new complex ideas by combining simple ideas in new ways. We can form abstract ideas by separating out what is specific to the idea of particular objects and retaining what is the same between several different ideas. Although these complex ideas are not always the objects of experience, they still are derived from experience because they depend on simple ideas that we receive from experience. If these explanations are successful, then we have little reason to believe our ideas are innate; instead, Locke concludes, all our ideas depend on experience.

c. No Innate Knowledge

Locke is also an empiricist about knowledge. Yet many philosophers at the time argued that some knowledge is innate. Locke responds to two such arguments: The Argument from Universal Consent and The Priority Argument. He argues that neither of these arguments are successful.

i. The Argument from Universal Consent

Many philosophers at the time disagreed with Locke’s empiricism. Some asserted that knowledge of God and knowledge of morality are innate, and others claimed that knowledge of a few basic axioms such as the Law of Identity and the Law of Non-Contradiction are innate. Take p as any proposition such as those supposed to be innate. One argument, which Locke criticizes, uses universal consent to try to prove that some knowledge is innate:

Argument from Universal Consent:

-

- Every person believes that p.

- If every person believes that p, then knowledge of p is innate.

- So, knowledge of p is innate.

Locke argues that both premises of the Argument from Universal Consent are false because there is no proposition which every person consents to, and, even if there were universal consent about a proposition, this does not prove that it is innate.

Locke says Premise 1 is false because no proposition is universally believed (2.2.5). For example, if p = “God exists,” then we know not everyone believes in God. And although philosophers sometimes assert that basic logical principles such as the Law of Non-Contradiction are innate, most people have not ever even thought about that principle, much less believed it to be true. We can know from experience, then, that premise 1 as stated is false. Perhaps premise 1 can be saved from Locke’s criticism by insisting that everyone who rationally thinks about it will believe the proposition (1.2.6) (Leibniz defends this view). Even if premise 1 can be revised so that it is not obviously false, Locke still thinks the argument fails because premise 2 is false.

Premise 2 is false for two reasons. First, premise 2 would prove too much. Usually, proponents of innate knowledge think there are only a few basic principles that are innately known (1.2.9-10). Locke argues, though, that every rational person who thinks about it would consent to all of the theorems of geometry, and “a million of other such propositions” (1.2.18), and thus premise 2 would count way too many truths as “innate” knowledge (1.2.13-23). Second, some things are obviously true, and so the fact that everyone believes them does not prove that they are innate (4.7.9). In Book 4, Locke sets out to explain how all of our knowledge comes from reason and experience and, if he is successful, then universal consent by rational adults would not imply that the knowledge is innate (1.2.1). Hence, premise 2 is false.

Sometimes innate instincts are mistaken for an example of innate knowledge. For example, we are born with a natural desire to eat and drink (2.21.34), and this might be misconstrued as innate knowledge that we should eat and drink. But this natural desire should not be confused with knowledge that we should eat and drink. Traditionally, knowledge has been defined as justified-true-belief, whereas Locke describes knowledge as a kind of perception of the truth. On either conception, knowledge requires us to be aware of a reason for believing the truth. Locke can grant that a newborn infant has an innate desire for food while denying that the infant knows that it is good to eat food. Innate instinct or other natural capacities, then, are not the same as innate knowledge.

Locke’s criticism of innate knowledge can be put in the form of a dilemma (2.2.5). Either innate knowledge is something which we are aware of at birth or it is something we become aware of only after thinking about it. Locke objects that if we are unaware of innate knowledge, then we can hardly be said to know it. But if we become aware of the “innate” knowledge only after thinking about it, then “innate” knowledge just means that we have the capacity to know it. In that case, though, all knowledge would be innate, which is not typically what the rationalist wants to claim.

ii. The Priority Thesis

Some assert that we have innate knowledge of a few basic logical principles, or “maxims”, and that this is how we are able to come to know other things. Call this the Priority Thesis. Locke criticizes the Priority Thesis and explains how we can attain certain knowledge without it.

Locke and the advocates of the Priority Thesis disagree both about (i) what is known first and (ii) what is known on the basis of other things. According to the Priority Thesis, we first have innate knowledge of general maxims and then we have knowledge of particular things on the basis of these general maxims. Locke disagrees on both counts. He thinks we first have knowledge of particular things and therefore denies that we know them because of the general maxims.

Some rationalists, such as Plato and Leibniz, hold that knowledge of particulars requires prior knowledge of abstract logical concepts or principles. For example, knowing that “white is white” and “white is not black” is thought to depend on prior knowledge of the general Law of Identity. On this view, we can know that “white is white” only because we recognize it as an instance of the general maxim that every object is identical to itself.

Locke rejects the Priority Thesis. First, he uses children as empirical evidence that people have knowledge of particulars before knowledge of general maxims (1.2.23; 4.7.9). He therefore denies that we need knowledge of maxims before we can have knowledge of particulars, as the Priority Thesis asserts. Second, he thinks he can explain how we get knowledge of particulars without the help of the general maxim. For example, “white is white” and “white is not black” are self-evident claims: we do not need any other information other than the relevant ideas to know that it is true, and once we have those ideas it is immediately obvious the propositions are true. Locke argues that we cannot be more certain of any general maxim than these obvious truths about the particulars, nor would knowing these general maxims “add anything” to our knowledge about them (4.7.9). In short, Locke thinks that knowledge of the particulars does not depend on knowledge of general maxims.

Locke argues a priori knowledge should not be confused with innate knowledge (4.7.9); innate knowledge is knowledge we are born with, whereas a priori knowledge is knowledge we acquire by reflecting on our ideas. For example, we can have a priori knowledge that “white is white.” The idea of white must come from experience. But once we have that idea, we do not need look at a bunch of white things in order to confirm that all the white things are white. Instead, we know by thinking about it that whatever is white must be white. Rationalists, such as Leibniz, sometimes argue that we become fully conscious of innate knowledge only by using a priori reasoning. Again, though, Locke argues that if it is not conscious then it is not something we really know. If we only come to know it when we engage in a priori reasoning, then we should say that we learned it by reasoning rather than positing some unconscious knowledge that was there all along. However, consistent with his empiricism, Locke denies that we can know that objects exist and what their properties are just by a priori reasoning.

Locke rejects innate knowledge. Instead, he thinks we must acquire knowledge from reasoning and experience.

2. Empiricist Account of Knowledge

In Book 4 of the Essay, Locke develops his empiricist account of knowledge. Empiricism emphasizes knowledge from empirical observation, but some knowledge depends only on a reflection of our ideas received from experience. This section explains the role of reason and empirical observation in Locke’s theory of knowledge.

a. Types of Knowledge

Locke categorizes knowledge in two ways: by what we know and by how we know it. As for what we can know, he says there are “four sorts” of things we can know (4.1.3):

-

- identity or diversity

- relation

- coexistence or necessary connection

- real existence

Knowledge of identity is knowing that something is the same, such as “white is white,” and knowledge of diversity is knowing that something is different, such as “white is not black” (4.1.4). Locke thinks this is the most obvious kind of knowledge and all other knowledge depends on this.

Knowledge of relation seems to be knowledge of necessary relations. He denies we can have universal knowledge of contingent relations (4.3.29). Technically, the categories of identity and necessary connections are both necessary relations, but they are important and distinctive enough to merit their own categories (4.1.7). Knowledge of relation, then, is a catch-all category that includes knowledge of any necessary relation.

Knowledge of coexistence or necessary connection concerns the properties of objects (4.1.6). If we perceive a necessary connection between properties A and B, then we would know that “all A are B.” However, Locke thinks this a priori knowledge of necessary connection is incredibly limited: we can know that figure requires extension, and causing motion by impulse requires solidity, but little else (4.3.14). In general, Locke denies that we can have a priori knowledge of the properties of objects (4.3.14; 4.3.25-26; 4.12.9). Alternatively, if we observe that a particular object x has properties A and B, then we know that A and B “coexist” in x (4.3.14). For example, we can observe that the same piece of gold is yellow and heavy.

Finally, knowledge of real existence is knowledge that an object exists (4.1.7 and 4.11.1). Knowledge of existence includes knowledge of the existence of the self, of God, and of material objects.

Locke also divides knowledge by how we know things (4.2.14):

-

- intuitive knowledge

- demonstrative knowledge

- sensitive knowledge

Intuitive knowledge comes from an immediate a priori perception of a necessary connection (4.2.1). Demonstrative knowledge is based on a demonstration, which is the perception of an a priori connection that is perceived by going through multiple steps (4.2.2). For example, the intuitions that “A is B” and “B is C” can be combined into a demonstration to prove that “A is C.” Finally, the sensation of objects provides “sensitive” knowledge (or knowledge from sensation) that those objects exist and have certain properties (4.2.14).

Locke describes intuitive, demonstrative, and sensitive knowledge as “three degrees of knowledge” (4.2.14). Intuitive knowledge is the most certain. It includes only things that the mind immediately sees are true without relying on any other information (4.2.1). The next degree of certainty is demonstrative knowledge, which consists in a chain of intuitively known propositions (4.2.2-6). This is less certain than intuitive knowledge because the truth is not as immediately obvious. Finally, sensitive knowledge is the third degree of knowledge.

There is considerable scholarly disagreement about Locke’s account of sensitive knowledge, or whether it even is knowledge. According to the standard interpretation, Locke thinks that sensitive knowledge is certain, though less certain than demonstrative knowledge. Alternatively, Samuel Rickless argues that, for Locke, sensitive knowledge is not, strictly speaking, knowledge at all. For knowledge requires certainty and Locke makes it clear that sensitive knowledge is less certain than intuitive and demonstrative knowledge. Locke also introduces sensitive knowledge by saying it is less certain and only “passes under the name knowledge” (4.2.14), perhaps implying that it is called “knowledge” even though it is not technically knowledge. However, in favor of the standard interpretation, he does call sensitive knowledge “knowledge” and describes sensitive knowledge as a kind of certainty (4.2.14). This encyclopedia article follows the standard interpretation.

Putting together what we know with how we know it: we can have intuitive knowledge of identity, and some necessary relations, and of our own existence (4.9.1); we can have demonstrative knowledge of some necessary relations (for example, in geometry), and of God’s existence (4.10.1-6); and we can then have sensitive knowledge of the existence of material objects and the co-existence of the properties of those objects (for example, this gold I see is yellow).

b. A Priori Knowledge

Both early modern rationalist and empiricist philosophers accept a priori knowledge. For example, they agree that we can have a priori knowledge of mathematics. Rationalists disagree about what we can know a priori. They tend to think we can discover claims about the nature of reality by a priori reasoning, whereas Locke and the empiricists think that we must instead rely on experience to learn about the natural world. This section explains what kinds of a priori knowledge Locke thinks we can and cannot have.

Locke defines knowledge as the perception of an agreement (or disagreement) between ideas (4.1.2). This definition of knowledge fits naturally, if not exclusively, within an account of a priori knowledge. Such knowledge relies solely on a reflection of our ideas; we can know it is true just by thinking about it.

Some a priori knowledge is (what Kant would later call) analytic. For example, knowledge of claims like “gold is gold” does not depend on empirical observation. We immediately and intuitively perceive that it is true. For this reason, Locke calls knowledge of identity “trifling” (4.8.2-3). Less obviously, we can have a priori knowledge that “gold is yellow.” According to Locke’s theory of ideas, the complex idea of gold is composed of the simple ideas of yellow, heavy, and so on. Thus, saying “gold is yellow” gives us no new information about gold and is, therefore, analytic (4.8.4).

We can also have (what Kant would later call) synthetic a priori knowledge. Synthetic propositions are “instructive” (4.8.3) because they give us new information. For example, a person might have the idea of a triangle as a shape with three sides without realizing that a triangle also has interior angles of 180 degrees. So, the proposition “a triangle has interior angles equal to 180 degrees” goes beyond the idea to tell us something new about a triangle (4.8.8), and thus is synthetic. Yet it can be proven, as a theorem in geometry, that the latter proposition is true. Further, this proof is a priori since the proof relies only on our idea of a triangle and not the observation of any particular triangle. So, we can know of synthetic a priori propositions.

Locke thinks we can have synthetic a priori knowledge of mathematics and morality. As mentioned above, any theorem in geometry will be proven a priori yet the theorem gives us new information. Locke claims we can prove moral truths in the same way (4.3.18 and 4.4.7). Yet, while moral theory is generally done by reflecting on our ideas, few have agreed with Locke that we can have knowledge as certain and precise about morality as we do of mathematics.

However, Locke denies that we can have synthetic a priori knowledge of the properties of material objects (4.3.25-26). Such knowledge would need to be instructive, and so tell us something new about the properties of the object, and yet be discovered without the help of experience. Locke argues, though, the knowledge of the properties of objects depends on observation. For example, if “gold” is defined as a yellow, heavy, fusible material substance, we might wonder whether gold is also malleable. But we do not perceive an a priori connection between this idea of gold and being malleable. Instead, we must go find out whether gold is malleable or not: “Experience here must teach me, what reason cannot” (4.12.9).

c. Sensitive Knowledge

Locke holds that empirical observation can give us knowledge of material objects and their properties, but he denies that we can have any sensitive knowledge (or knowledge from sensation) about material objects that goes beyond our experience.

Sensation gives us sensitive knowledge of the existence of external material objects (4.2.14). However, we can know that x exists while we perceive it but we cannot know that it continues to exist past the time we observe it: “this knowledge extends as far as the present testimony of the senses…and no farther” (4.11.9). For example, suppose we saw a man five minutes ago. We can be certain he existed while we saw him, but we “cannot be certain, that the same man exists now, since…by a thousand ways he may cease to be, since [we] had the testimony of the senses for his existence” (4.11.9). So, empirical observation can give us knowledge, but such knowledge is strictly limited to what we observe.

Empirical observation can also give us knowledge of the properties of objects (or knowledge of “coexistence”). For example, we learn from experience that the gold we have observed is malleable. We might reasonably conclude from this that all gold, including the gold we have not observed, is malleable. But we might turn out to be wrong about this. We have to rely on experience and see. So, for this reason, Locke considers judgments that go beyond what we directly observe “probability” rather than certain knowledge (4.3.14; 4.12.10).

Despite Locke’s insistence that we can have knowledge from experience, there are potential problems for his view. First, it is not clear how, if at all, sensitive knowledge is consistent with his general definition of knowledge. Second, Locke holds that we can only ever perceive the ideas of objects, and not the objects themselves, and so this raises questions about whether we can really know if external objects exist.

i. The Interpretive Problem

Locke’s description of sensitive knowledge (or knowledge from sensation) seems to conflict with his definition of knowledge. Some have thought that he is simply inconsistent, while others try to show how sensitive knowledge is consistent with his definition of knowledge.

The problem arises from Locke’s definition of knowledge. He defines knowledge as the perception of an agreement between ideas (4.1.2). But the perception of a connection between ideas appears to be an a priori way of acquiring knowledge rather than knowledge from experience. If we could perceive a connection between the idea of a particular man (for example, John) and existence, then we could know a priori, just by reflecting on our ideas, that the man exists. But this is mistaken. The only way to know if a particular person exists is from experience (see 4.11.1-2, 9). So, perceiving connections between ideas appears to be ill-suited for knowledge of existence.

Yet suppose we do see that John exists. There seems to be only one relevant idea needed for this knowledge: the sensation of John. It seems any other idea is unnecessary to know, on the basis of observation, that John exists. With what other idea, then, does sensitive knowledge depend? This is where interpretations of Locke diverge.

Some interpreters, such as James Gibson, hold that Locke is simply inconsistent. He defines knowledge as the perception of an agreement between two ideas, but sensitive knowledge is not the perception of two ideas; sensitive knowledge consists only in the sensation of an object. The advantage of this interpretation is that it just accepts at face value his definition of knowledge and his description of sensitive knowledge in the Essay. However, perhaps there is a consistent interpretation available. Moreover, Locke elsewhere identifies the two ideas that are supposed to agree, and so he thinks his account of sensitive knowledge fits his general definition.

Other interpreters turn to the passage in which Locke identifies the two ideas that in sensitive knowledge are supposed to agree. Locke explains:

Now the two ideas, that in this case are perceived to agree, and thereby do produce knowledge, are the idea of actual sensation (which is an action whereof I have a clear and distinct idea) and the idea of actual existence of something without me that causes that sensation. (Works v. 4, p. 360)

On one interpretation of this passage, by Lex Newman and others, the idea of the object (the sensation) is perceived to agree with the idea of existence. Locke describes the first idea as “the idea of actual sensation” and, on this interpretation, that means the sensation of the object. The second idea is “the idea of actual existence.” Excluding the parenthetical comment, this is a natural way to interpret the two ideas Locke identifies here. On this view, then, we know an object x exists when we perceive that the sensation of x agrees with the idea of existence.

On a second interpretation of the passage, by Jennifer Nagel and Nathan Rockwood, the idea of the object (the sensation) is perceived to agree with the idea of reflection of having a sensation. Here the “the idea of actual sensation” is not the sensation of the object; rather, it is a second-order awareness of having a sensation or, in other words, identifying the sensation as a sensation. This is because Locke describes the first idea as “the idea of actual sensation” and then follows that with the parenthetical comment “(which is an action…)”; an external object is not an action, but having a sensation is an action. So, perhaps the first idea should be taken as an idea of having a sensation. If so, then that makes the second idea the sensation of the object. This better captures Locke’s description of the first idea as an idea of an action. In any case, on this interpretation, we know an object x exists when we have the sensation of x and identify that sensation as a sensation.

However, the interpretive problem is resolved, there remains a worry that Locke’s view inevitably leads to skepticism.

ii. The Skeptical Problem

The skeptical problem for Locke is that perceiving ideas does not seem like the kind of thing that can give us knowledge of actual objects.

Locke has a representational theory of perception. When we perceive an object, we are immediately aware of the idea of the object rather than the external object itself. The idea is like a mental picture. For example, after seeing the photograph of Locke above, we can close our ideas and picture an image of John Locke in our minds. This mental picture is an idea. According to Locke, even if he were right here before our very eyes, we would directly “see” only the idea of Locke rather than Locke himself. However, an idea of an object represents that object. Just as looking at a picture can give us information about the thing it represents, “seeing” the idea of Locke allows us to become indirectly aware of Locke himself.

Locke’s representational theory of perception entails that there is a veil of perception. On this view, there are two things: the object itself and the idea of the object. Locke thinks we can never directly observe the object itself. There is, then, a “veil” between the ideas we are immediately aware of and the objects themselves. This raises questions about whether our sensation of objects really do correspond to external objects.

Berkeley and Thomas Reid, among others, object that Locke’s representational theory of perception inevitably leads to skepticism. Locke admits that, just as a portrait of a man does not guarantee that the man portrayed exists, the idea of a man does not guarantee that the man exists (4.11.1). So, goes the objection, since on Locke’s view we can only perceive the idea, and not the object itself, we can never know for sure the external object really exists.

While others frequently accuse Locke’s view of inevitably leading to skepticism, he is not a skeptic. Locke offers four “concurrent reasons” to believe sensations correspond to external objects (4.11.3). First, we cannot have an idea of something without first having the sensation of it, suggesting that it has an external (rather than an internal) cause (4.11.4). Second, sensations are involuntary. If we are outside in the daylight, we might wish the sun would go away, but it does not. Hence, it appears the sensation of the sun has an external cause (4.11.5). Third, some veridical sensations cause pain in a way that merely dreaming or hallucinating does not (4.11.6). For example, if we are unsure if the sensation of a fire is a dream, we can stick our hand into the fire and “may perhaps be wakened into a certainty greater than [we] could wish, that it is something more than bare imagination” (4.11.8). Fourth, the senses confirm each other: we can often see and feel an object, and in this way the testimony of one sense confirms that of the other (4.11.7). In each case, Locke argues that sensation is caused by an external object and thus the external object exists.

Perhaps the external cause of sensation can provide a way for Locke to escape skepticism. As seen above, he argues that sensation has an external cause. We thus have some reason to believe that our ideas correspond to external objects. Even if there is a veil of perception, then, sensations might nonetheless give us a reason to believe in external objects.

d. The Limits of Knowledge

One of the stated purposes of the Essay is to make clear the boundary between, on the one hand, knowledge and certainty, and, on the other hand, opinion and faith (1.1.2).

For Locke, knowledge requires certainty. As explained above, we can attain certainty by perceiving an a priori necessary connection between ideas (either by intuition or demonstration) or by empirical observation. In each case, Locke thinks, the evidence is sufficient for certainty. For example, we can perceive an a priori necessary connection between the idea of red and the idea of a color, and thus we see that it must be true that “red is a color.” Given the evidence, there is no possibility of error and hence we are certain. More controversially, Locke also thinks that direct empirical observation is sufficient evidence for certainty (4.2.14).

Any belief that falls short of certainty is not knowledge. Suppose we have seen many different ravens in a wide variety of places over a long period of time, and so far, all the observed ravens have been black. Still, we do not perceive an a priori necessary connection between the idea of a raven and the idea of black. It is possible, though perhaps unlikely, that we will discover ravens of a different color in the future. Yet no matter how high the probability is that all ravens are black, we cannot be certain that all ravens are black. So, Locke concludes, we cannot know for sure that all ravens are black (4.3.14). There is a sharp boundary between knowledge and belief that falls short of knowledge: knowledge is certain, whereas other beliefs are not.

Locke describes knowledge as “perception” whereas judgment is a “presumption” (4.14.4). To perceive that p is true guarantees the truth of that proposition. But we can presume the truth of p even if p is false. For example, given that all the ravens we have seen thus far have been black, it would be reasonable for us to presume that “all ravens are black” even though we are not certain this is true. Thus, judgment involves some epistemic risk of being wrong, whereas knowledge requires certainty.

In his account of empirical knowledge, Locke takes the knowledge-judgment distinction to the extreme in two important ways. First, while we can know that an object exists while we observe it, this knowledge does not extend at all beyond what we immediately observe. For example, suppose we see John walk into his office. While we see John, we know that John exists. Ordinarily, if we just saw John walk into his office a mere few seconds ago, we would say that we “know” that John exists and is currently in his office. But Locke does not use the word “know” in that way. He reserves “knowledge” for certainty. And, intuitively, we are more certain that John exists when we see him than when we do not see him any longer. So, the moment John shuts the door, we no longer know he exists. Locke concedes it is overwhelmingly likely that John continues to exist after shutting the door, but “I have not that certainty of it, which we strictly call knowledge; though the likelihood of it puts me past doubt, …this is but probability, not knowledge” (4.11.9). So, we can know something exists only for the time that we observe it.

Second, any scientific claim that goes beyond what is immediately observed cannot be known to be true. We know that observed ravens have all been black. From this we may presume, but cannot know, that unobserved ravens are all black (4.12.9). We know that friction of observed (macroscopic) objects causes heat. By analogy, we might reasonably guess, but cannot know, that friction among unobserved particles heats up the air (4.16.12). In general, experience of observed objects cannot give us knowledge of any unobserved objects. This distinction between knowledge of the observed versus uncertainty (or even skepticism) about the unobserved remains important for contemporary empiricism in the philosophy of science.

Thus, Locke, and empiricists after him, sharply distinguish between the observed and the unobserved. Further, he maintains that we can knowledge of the observed but never of the unobserved. When our evidence falls short of certainty, Locke holds that probable evidence ought to guide our beliefs.

3. Judgment (Rational Belief)

Locke holds that all rational beliefs required evidence. For knowledge, that evidence must give us certainty: there must not be the possibility of error given the evidence. But beliefs can be rational even if they fall short of certainty so long as the belief is based on what is probably true given the evidence.

There are two conditions for rational judgment (4.15.5). First, we should believe what is most likely to be true. Second, our confidence should be proportional to the evidence. The degrees of probability, given the evidence, depends on our own knowledge and experience and the testimony of others (4.15.4).

The three kinds of rational judgment that Locke is most concerned with are beliefs based on science, testimony, and faith.

a. Science

Locke was an active participant in the scientific revolution and his empiricism was an influential step towards the modern view of science. He was close associates with Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton, and was also a member of the Royal Society, a group of the leading scientists of the day. He describes himself not as one of the “master-builders” who are making scientific discoveries, but as an “under-labourer” who would be “clearing Ground a little, and removing some of the Rubbish, that lies in the way to knowledge” about the natural world (Epistle to the Reader, p. 9-10). Locke contributes to the scientific revolution, then, by developing an empiricist epistemology consistent with the principles of modern science. His emphasis on the need for empirical observation and the uncertainty of general conclusions of science helped shaped the modern view of science as being a reliable, though fallible, source of information about the natural world.

The prevailing view of science at the time was the Aristotelian view. According to Aristotle, a “science” is a system of knowledge with a few basic principles that are known to be true and then all other propositions in the science are deduced from these basic principles. (On this view, Euclid’s geometry is the paradigmatic science.) The result of Aristotelian science, if successful, is a set of necessary truths that are known with perfect certainty. While Locke is willing to grant that God and angels might have such knowledge of nature, he emphatically denies that us mere mortals are capable of this kind of certainty about a science of nature (4.3.14, 26; 4.12.9-10).

In Locke’s view, an Aristotelian science of nature would require knowledge of the “real essence” of material objects. The real essence of an object is a set of metaphysically fundamental properties that make an object what it is (3.6.2). Locke draws a helpful analogy to geometry (4.6.11). We can start with the definition of a triangle as a shape with three sides (its real essence) and then we can deduce other properties of a triangle from that definition (such as having interior angles of a 180 degrees). Locke thinks of the real essence of material objects in the same kind of way. For example, the real essence of gold is a fundamental set of properties, and this set of properties entails that gold is yellow, heavy, fusible, and so on. Now, if we knew the real essence of gold, then we could deduce its other properties in the same way that we can deduce the properties of a triangle. But, unlike with a triangle, we do not know the real essence of gold, or of any other material object. Locke thinks the real essence of material objects is determined by the structure of imperceptibly small particles. Since, at that time, we could not see the atomic structure of different material substances, Locke thinks we cannot know the real essences of things. For this reason, he denies that we can have an Aristotelian science of nature (4.3.25-26).

The big innovation in Locke’s philosophy of science is the introduction of the concept of a “nominal essence” (3.6.2). It is often assumed that when we classify things into natural kinds that this tracks some real division in nature. Locke is not so sure. We group objects together, and call them by the same name, because of superficial similarities. For example, we see several material substances that are yellow, heavy, and fusible, and we decide to call that kind of stuff “gold.” The set of properties we use to classify gold as gold (that is, being yellow, heavy, and fusible) is the “nominal” essence of gold (“nominal” meaning here “in name only”). Locke does not think that the nominal essence is the same as the real essence. The real essence is, at the time, the unobservable chemical structure of the object, whereas the nominal essence is the set of observable qualities we use to classify objects. Locke therefore recognizes that there is something artificial about the natural kinds identified by scientists.

In general, Locke denies that we can have synthetic a priori knowledge of material objects. Because we can have knowledge of only the nominal essence of an object, and not its real essence, we are unable to make a priori inferences about what other properties an object has. For example, if “gold” is defined as a yellow, heavy, fusible material substance, then “gold is yellow” would be analytic. The claim “gold is malleable” would be synthetic, because it gives us new information about the properties of gold. There is no a priori necessary connection between the defining properties of gold and malleability. Therefore, we cannot know with certainty that all gold is malleable. For this reason, Locke says, “we are not capable of scientifical knowledge; nor shall [we] ever be able to discover general, instructive, unquestionable truths concerning” material objects (4.3.26).

Most of Locke’s comments about science emphasize that we cannot have knowledge, but this does not mean that beliefs based on empirical science are unjustified. In Locke’s view, a claim is “more or less probable” depending on “the frequency and constancy of experience” (4.15.6). The more frequently it is observed that “A is B” the more likely it would be that, on any particular occasion, “A is B” (4.16.6-9). For example, since all the gold we have observed has been malleable, it is likely that all gold, even the gold we have not observed, is also malleable. In this way, we can use empirical evidence to make probable inferences about what we have not yet observed.

For Locke, then, all knowledge and rational beliefs about material objects must be grounded in empirical observation, either by observation or probable inferences made from observation.

b. Testimony

Testimony can be a credible source of evidence. Locke develops an early and influential account of when testimony should be believed and when it should be doubted.

In Locke’s view, we cannot know something on the basis of testimony. Knowledge requires certainty, but there is always the possibility that someone’s testimony is mistaken: perhaps the person is lying, or honestly stating her belief but is mistaken. So, although credible testimony is likely to be true, it is not guaranteed to be true, and hence we cannot be certain that it is so.

Yet credible testimony is often likely to be true. A high school math teacher knows a theorem in geometry is true because she has gone through the steps of the proof. She might then tell her students that the theorem is true. If they believe her on the basis of her testimony, rather than going through the steps of the proof themselves, then they do not know the theorem is true; yet they would have a rationally justified belief because it is likely to be true given the teacher’s testimony (4.15.1).

Whether someone’s testimony should be believed depends on (i) how well it conforms with our knowledge and past experience and (ii) the credibility of the testimony. The credibility of testimony depends on several factors (4.15.4):

-

- the number of people testifying (more witnesses provide more evidence)

- the integrity of the people

- the “skill” of the witnesses (that is, how well they know what they are talking about)

- the intention of the witnesses

- the consistency of the testimony

- contrary testimonies (if any)

We can be confident in a testimony that conforms with our own past experience and the reported experience of others (4.16.6). As noted above, the more frequently something is observed the more likely it happened on a given occasion. For example, in our past experience fire has always been warm. When we have the testimony that, on a specific occasion, a fire was warm, then we should believe it with the utmost confidence.

We should be less confident in the testimony when it conflicts with our past experience (4.16.9). Locke relates the story of the King of Siam who, knowing only the warm climate of south-east Asia, is told by a traveler that in Europe it gets so cold that water becomes solid (4.15.5). On the one hand, the King has credible testimony that water becomes solid. On the other hand, this conflicts with his past experience and the reported experience of those he knows. Locke implies that the King rationally doubted the testimony because, in this case, the evidence from the King’s experience is greater than the evidence from testimony. Experience does not always outweigh the evidence from testimony. The evidence from testimony depends in part on the number of people: “as the relators are more in number, and of more credit, and have no interest to speak contrary to the truth, so that matter of fact is like to find more or less belief.” So, if there is enough evidence from testimony, then that could in principle outweigh the evidence from experience.

That the evidence from testimony can sometimes outweigh the evidence from experience is particularly relevant to the testimony of miracles. Hume famously argues that because the testimony of miracles conflict with our ordinary experience we should never believe the testimony of a miracle. Locke, however, remains open to the possibility that the evidence from testimony could outweigh the evidence from experience. Indeed, he argues that we should believe in revelation, particularly in the Bible, because of the testimony of miracles (4.16.13-14; 4.19.15).

Although Locke thinks that testimony can provide good evidence, it does not always provide good evidence. We should not believe “the opinion of others” just because they say something is true. One difference between the testimony Locke accepts as credible and the testimony he rejects is that credible testimony begins with knowledge, whereas the testimony of “the opinion of others” is merely speculation of things “beyond the discovery of the senses” and so are “not capable of any such testimony” (4.16.5). In taking this attitude, Locke follows the Enlightenment sentiment of rejecting authority. Speculative theories should not be believed based on testimony. Instead, we should base our opinions on observation and our own reasoning.

Testimony provides credible evidence when the testimony makes it likely that a claim is true. When the person is in a position to know, either from reasoning or from experience, it can be reasonable for us to believe the person’s testimony.

c. Faith

Locke insists that all of our beliefs should be based on evidence. While this seems obviously true for most beliefs, some people want to make an exception for religion. Faith is sometimes thought to be belief that goes beyond the evidence. However, Locke thinks that, if faith is to be rational, even faith must be supported by evidence.

Some religious claims can be proven by the use of reason or natural theology. For example, Locke makes a cosmological argument for the existence of God (4.10.1-6). He thinks that, given this proof from natural theology, we can know that God exists. This kind of belief in God is knowledge and not faith, since faith implies some uncertainty.

Many religious claims cannot be proven by the use of natural reason; we must instead rely on revelation. Locke defines faith as believing something because God revealed it (4.18.2). We do not perceive the truth, as we do in knowledge, but instead presume that it is true because God has told us so in a revelation. Just as human testimony can provide evidence, revelation, as God’s testimony, can provide evidence. Yet revelation is better evidence than human testimony because human testimony is fallible whereas divine revelation is infallible (4.18.10).

We should believe whatever God has revealed, but we first must have good reason to believe that God revealed it. This makes faith dependent on reason. For reason must judge whether something is a genuine revelation from God (4.18.10). Further, we must be sure that we interpret the revelation correctly (4.18.5). Since whatever God reveals is guaranteed to be true, if we have good evidence that God revealed that p, then that provides us with evidence that p is true. In this way, Locke can insist that all religious beliefs require evidence and yet believe in the truths of revealed religion.

Locke only admits publicly available evidence as evidence for revelation. He criticizes “enthusiasm” which is, as he describes it, believing (what they claim is) a revelation without evidence that it is a revelation (4.19.4). The enthusiast believes God has revealed that p only because it seems to the person to have come from God. Some religious epistemologists take religious experience as evidence for religious belief, but Locke is skeptical of religious experience. Locke demands that this subjective feeling that God revealed p be backed up with concrete evidence that it really did come from God (4.19.11). Instead of relying on private religious experience, Locke appeals to miracles as publicly available evidence supporting revelation (4.16.13; 4.19.14-15).

Locke also limits the kind of things that can be believed on the basis of revelation. Some propositions are according to reasons, others are contrary to reason, and still others are above reason. Only the things above reason can appropriately be believed on the basis of revelation (4.18.5, 7).

Claims that are “according to reason” should not be believed on the basis of revelation because we already have all the evidence we need. By “according to reason” Locke means those propositions that we have a priori knowledge of, either from intuition or demonstration. If we already have a priori knowledge that p, then we need no further evidence. In that case, revelation would be useless because we already have certainty without it.

Claims that are “contrary to reason” should not be believed on the basis of revelation because we know with certainty that they are false. By “contrary to reason” Locke means those propositions that we have a priori knowledge are false. If it is self-evident that p is false, then we cannot rationally believe it under the pretense that it was revealed by God. For God only reveals true things, and if we know with certainty p is false, then we know for sure that God did not reveal it.

Faith, then, concerns those things that are “above reason.” By “above reason” Locke means those propositions that cannot be proven one way or the other by a priori reasoning. For example, the Bible teaches that some of the angels rebelled and were kicked out of heaven, and it predicts that the dead will rise again at the last day. We cannot know with certainty these claims are true, nor that they are false. We must instead rely on revelation: “faith gave the determination, where reason came short; and revelation discovered which side the truth lay” (4.18.9).

There is some disagreement about how much weight Locke gives revelation when there is conflicting evidence. For example, suppose we have good reason to believe that God revealed that p to Jesus, but that given our other evidence p appears to be false. Locke says “evident revelation ought to determine our assent even against probability” (4.18.9). On one interpretation, if there is good reason to believe God revealed that p we should believe p no matter how likely it is that p is false given our other evidence. On another interpretation, Locke carefully sticks with his evidentialism: if the evidence that God revealed p outweighs the evidence that p is false, then we should believe that p; but if the evidence that p is false outweighs the evidence that God revealed it, then we should not believe p (nor that God revealed it).

According to Locke, God created us as rational beings so that we would form rational beliefs based on the available evidence, and he thinks religious beliefs are no exception.

4. Conclusion

Locke makes a number of important contributions to the history of epistemology.

He makes the most sustained criticism of innate ideas and innate knowledge, which convinced generations of later empiricists such as Berkeley and Hume. He argues that there is no universal knowledge we are all born with and, instead, all our ideas and knowledge depend on experience.

He then develops an explanation for how we acquire knowledge that is consistent with his empiricism. All knowledge is either known a priori or based on empirical evidence. Later empiricists, such as Hume and the logical positivists, follow Locke in thinking some knowledge is known a priori whereas other knowledge is based on empirical evidence. However, Locke allows for synthetic a priori knowledge whereas Hume and the logical positivists hold that all a priori knowledge is analytic.

Locke’s emphasis on the need for the empirical evidence also supported the developments of the scientific revolution. Locke argues that a priori knowledge of nature is not possible, a thesis for which Hume would later become more famous. Rather than a priori knowledge of nature, Locke emphasizes the need for empirical evidence. Although inferences from empirical observations cannot give us certainty, Locke thought that they can give us evidence about what is most likely to be true. So, science should be both based on empirical evidence and acknowledge its uncertainty. In this way, Locke helped shift attitudes about science away from the Aristotelian view towards the modern conception of empirical science that is always open to revision upon further observation.

Locke gives one of the earliest careful treatments of how testimony can serve as evidence. He argues that testimony should be evaluated by its internal consistency and consistency with other things we know, including past observations about similar cases. Hume later takes this view of testimony and then, as he famously argues, claims that since the testimony of miracles conflicts with past experience we should not believe the testimony of miracles.

Finally, Locke insists that religious belief should be based on evidence. Locke himself thought that there was sufficient evidence from the testimony of miracles and revelation to support his belief in Christianity. However, many have criticized Locke’s evidentialism for undermining the rationality of religious belief. Critics such as Hume agreed that religious belief needs to be supported by evidence, but they argue there is no good evidence, and hence religious belief is not rational. Others, such as William Paley, attempted to provide the evidence needed to support religious belief. Needless to say, whether there is good evidence for religion or not was just as controversial then as it is now, yet many agree with Locke that religious belief requires evidence.

The guiding principle of Locke’s epistemology is the need for evidence. We can acquire evidence from a priori reasoning, from empirical observation, or most often from inferences from empirical observation. Limiting our beliefs to those supported by evidence, Locke thinks, is the most reliable way to get at the truth.

5. References and Further Reading

a. Locke’s Works

- Locke, John. 1690/1975 An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (ed. Peter Nidditch). Oxford University Press, 1975.

- References to the Essay are cited by book, chapter, and section. For example, 2.1.2 is book 2, chapter 1, section 2.

- Locke, John, The Works of John Locke in ten volumes (ed. Thomas Tegg). London.

b. Recommended Reading

- Anstey, Peter. 2011. John Locke & Natural Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- This book is on Locke’s view of science and its relationship to Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton.

- Ayers, Michael. 1993. Locke: Epistemology and Ontology. New York: Routledge

- Volume 1 of this two-volume work is dedicated to Locke’s epistemology. It includes chapters on Locke’s theory of ideas, theory of perception, probable judgment, and knowledge.

- Gibson. James. 1917. Locke’s Theory of Knowledge and its Historical Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- This book gives a thorough overview of Locke’s epistemology with chapters showing how Locke’s view relates to other early modern philosophers such as Descartes, Leibniz, and Kant. The comparison of Locke and Kant on a priori knowledge is particularly helpful.

- Gordon-Roth, Jessica and Weinberg, Shelley. 2021. The Lockean Mind. New York: Routledge.

- A survey of all aspects of Locke’s philosophy by different scholars. It has several articles on Locke’s epistemology, including on Locke’s criticism of innate knowledge, account of knowledge, account of probable judgment, and religious belief, as well as his theory of ideas and theory of perception.

- Jacovides, Michael. 2017. Locke’s Image of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- This book is on Locke’s view of science and how Locke was influenced by and exerted an influence on scientific developments happening at the time.

- Nagel, Jennifer. 2014. Knowledge: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- This introduction to epistemology includes a chapter on the early modern rationalism-empiricism debate and a chapter on Locke’s view of testimony.

- Nagel, Jennifer. 2016. “Sensitive Knowledge: Locke on Skepticism and Sensation,” A Companion to Locke.

- A discussion of Locke’s account of sensitive knowledge and response to skepticism.

- Newman, Lex. 2007. “Locke on Knowledge.” Cambridge Companion to Locke’s Essay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- This is an accessible and excellent overview of Locke’s theory of knowledge.

- Newman, Lex. 2007. Cambridge Companion to Locke’s Essay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- A survey of Locke’s Essay by different scholars. It has several articles on Locke’s epistemology, including his criticism of innate knowledge, theory of ideas, account of knowledge, probable judgment, and religious belief.

- Chappell, Vere. 1994. The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- A survey of all aspects of Locke’s philosophy by different scholars. It includes articles on Locke’s theory of ideas, account of knowledge, and religious belief.

- Rickless, Samuel. 2007. “Locke’s Polemic Against Nativism.” Cambridge Companion to Locke’s Essay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- This is an accessible and excellent overview of Locke’s criticism of innate knowledge.

- Rickless, Samuel. 2014. Locke. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- This book is an introduction and overview of Locke’s philosophy, which includes chapters on Locke’s criticism of innate knowledge, account of knowledge, and religious belief.

- Rockwood, Nathan. 2018. “Locke on Empirical Knowledge.” History of Philosophy Quarterly, v. 35, n. 4.

- The article explains Locke’s view on how empirical observation can justify knowledge that material objects exist and have specific properties.

- Rockwood, Nathan. 2020. “Locke on Reason, Revelation, and Miracles.” The Lockean Mind (ed. Jessica Gordon-Roth and Shelley Weinberg). New York: Routledge.

- This article is a good introduction to Locke’s religious epistemology.

- Wolterstorff, Nicholas. 1996. John Locke and the Ethics of Belief. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- This book gives an overview of Locke’s epistemology generally and specifically his account of religious belief.

Author Information

Nathan Rockwood

Email: nathan_rockwood@byu.edu

Brigham Young University

U. S. A.