Truth

Philosophers are interested in a constellation of issues involving the concept of truth. For example, what makes an assertion be true? Surely the assertion has grounds and does not float in mid-air, so to speak. The grounds might involve a variety of things: our evidence, or the assertion’s correspondence with the world beyond the assertion, or the meanings of the concepts involved in the assertion, or the nature of mind, or our social conventions about making assertions, or some combination of these. A preliminary issue, although somewhat subsidiary, is to decide what sorts of things can be true. Is truth a property of assertions, or of sentences (which are linguistic entities in some language or other), or of propositions (nonlinguistic, abstract and timeless entities)? Is truth even a property? The principal issue is: What is truth? It is the problem of being clear about what you are saying, implying, and presupposing when you say some claim or other is true. The most important theories of truth are the Correspondence Theory, the Semantic Theory, the Deflationary Theory, the Coherence Theory, and the Pragmatic Theory. They are explained and compared here. Whichever theory of truth is advanced to settle the principal issue, there are a number of additional issues to be addressed:

- Can claims about the future be true now?

- Can there be some algorithm for finding truth – some recipe or procedure for deciding, for any claim in the system of, say, arithmetic, whether the claim is true?

- Can the predicate “is true” be completely defined in other terms so that it can be eliminated, without loss of meaning, from any context in which it occurs?

- To what extent do theories of truth avoid paradox?

- Is the goal of scientific research to achieve truth?

Table of Contents

- The Principal Problem

- What Sorts of Things are True (or False)?

- Ontological Issues

- Constraints on Truth and Falsehood

- Which Sentences Express Propositions?

- Problem Cases

- Correspondence Theory

- Tarski’s Semantic Theory

- Extending the Semantic Theory Beyond “Simple” Propositions

- Can the Semantic Theory Account for Necessary Truth?

- The Linguistic Theory of Necessary Truth

- Coherence Theories

- Postmodernism: The Most Recent Coherence Theory

- Pragmatic Theories

- Deflationary Theories

- Redundancy Theory

- Performative Theory

- Prosentential Theory

- Related Issues

- Beyond Truth to Knowledge

- Algorithms for Truth

- Can “is true” be Eliminated?

- Can a Theory of Truth Avoid Paradox?

- Is The Goal of Scientific Research to Achieve Truth?

- References and Further Reading

1. The Principal Problem

The principal problem is to offer a viable theory as to what truth itself consists in, or, to put it another way, “What is the nature of truth?” To illustrate with an example—the problem is not: Is it true that there is extraterrestrial life? The problem is: What does it mean to say that it is true that there is extraterrestrial life? Astrobiologists study the former problem; philosophers, the latter.

This philosophical problem of truth has been with us for a long time. In the first century AD, Pontius Pilate (John 18:38) asked “What is truth?” but no answer was forthcoming. The problem has been studied more since the turn of the twentieth century than at any other previous time. In the last one hundred or so years, considerable progress has been made in solving the problem. There is now light where there was darkness.

Here are two prominent philosophical positions about truth. We do not revise the truth’ we revise our beliefs about what is true. Also, ideally good inferences are truth-preserving.

The most widely accepted contemporary theories of truth are [i] the Correspondence Theory ; [ii] the Semantic Theory of Tarski and Davidson; [iii] the Deflationary Theory of Frege and Ramsey, [iv] the Coherence Theory , and [v] the Pragmatic Theory . These five theories are examined after addressing the following question.

2. What Sorts of Things are True (or False)?

Although we do speak of true friends and false identities, philosophers believe these are derivative uses of “true” and “false”. The central use of “true”, the more important one for philosophers, occurs when we say, for example, it’s true that Montreal is north of Pittsburgh. Here,”true” is contrasted with “false”, not with “fake” or “insincere”. When we say that Montreal is north of Pittsburgh, what sort of thing is it that is true? Is it a statement or a sentence or something else, a “fact”, perhaps? More generally, philosophers want to know what sorts of things are true and what sorts of things are false. This same question is expressed by asking: What sorts of things have (or bear) truth-values?

The term “truth-value” has been coined by logicians as a generic term for “truth or falsehood”. To ask for the truth-value of P, is to ask whether P is true or whether P is false. “Value” in “truth-value” does not mean “valuable”. It is being used in a similar fashion to “numerical value” as when we say that the value of “x” in “x + 3 = 7” is 4. To ask “What is the truth-value of the statement that Montreal is north of Pittsburgh?” is to ask whether the statement that Montreal is north of Pittsburgh is true or whether it is false. (The truth-value of that specific statement is true.)

There are many candidates for the sorts of things that can bear truth-values:

- statements

- sentence-tokens

- sentence-types

- propositions

- theories

- facts

|

|

- assertions

- utterances

- beliefs

- opinions

- doctrines

- etc.

|

a. Ontological Issues

What sorts of things are these candidates? In particular, should the bearers of truth-values be regarded as being linguistic items (and, as a consequence, items within specific languages), or are they non-linguistic items, or are they both? In addition, should they be regarded as being concrete entities, that is, things which have a determinate position in space and time, or should they be regarded as abstract entities, that is, as being neither temporal nor spatial entities?

Sentences are linguistic items: they exist in some language or other, either in a natural language such as English or in an artificial language such as a computer language. However, the term “sentence” has two senses: sentence-token and sentence-type. These three English sentence-tokens are all of the same sentence-type:

- Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun.

- Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun.

- Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun.

Sentence-tokens are concrete objects. They are composed of ink marks on paper, or sequences of sounds, or patches of light on a computer monitor, etc. Sentence-tokens exist in space and time; they can be located in space and can be dated. Sentence-types cannot be. They are abstract objects. (Analogous distinctions can be made for letters, for words, for numerals, for musical notes on a stave, indeed for any symbols whatsoever.)

Might sentence-tokens be the bearers of truth-values?

One reason to favor tokens over types is to solve the problems involving so-called “indexical” (or “token reflexive”) terms such as “I” and “here” and “now”. Is the claim expressed by the sentence-type “I like chocolate” true or false? Well, it depends on who “I” is referring to. If Jack, who likes chocolate, says “I like chocolate”, then what he has said is true; but if Jill, who dislikes chocolate, says “I like chocolate”, then what she has said is false. If it were sentence-types which were the bearers of truth-values, then the sentence-type “I like chocolate” would be both true and false – an unacceptable contradiction. The contradiction is avoided, however, if one argues that sentence-tokens are the bearers of truth-values, for in this case although there is only one sentence-type involved, there are two distinct sentence-tokens.

A second reason for arguing that sentence-tokens, rather than sentence-types, are the bearers of truth-values has been advanced by nominalist philosophers. Nominalists are intent to allow as few abstract objects as possible. Insofar as sentence-types are abstract objects and sentence-tokens are concrete objects, nominalists will argue that actually uttered or written sentence-tokens are the proper bearers of truth-values.

But the theory that sentence-tokens are the bearers of truth-values has its own problems. One objection to the nominalist theory is that had there never been any language-users, then there would be no truths. (And the same objection can be leveled against arguing that it is beliefs that are the bearers of truth-values: had there never been any conscious creatures then there would be no beliefs and, thus, no truths or falsehoods, not even the truth that there were no conscious creatures – an unacceptably paradoxical implication.)

And a second objection – to the theory that sentence-tokens are the bearers of truth-values – is that even though there are language-users, there are sentences that have never been uttered and never will be. (Consider, for example, the distinct number of different ways that a deck of playing cards can be arranged. The number, 8×1067 [the digit “8” followed by sixty-seven zeros], is so vast that there never will be enough sentence-tokens in the world’s past or future to describe each unique arrangement. And there are countless other examples as well.) Sentence-tokens, then, cannot be identified as the bearers of truth-values – there simply are too few sentence-tokens.

Thus both theories – (i) that sentence-tokens are the bearers of truth-values, and (ii) that sentence-types are the bearers of truth-values – encounter difficulties. Might propositions be the bearers of truth-values?

To escape the dilemma of choosing between tokens and types, propositions have been suggested as the primary bearers of truth-values.

The following five sentences are in different languages, but they all are typically used to express the same proposition or statement.

| Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun. |

|

[English] |

| Saturn je šestá planeta od slunce. |

|

[Czech] |

| Saturne est la sixième planète la plus éloignée du soleil. |

|

[French] |

|

|

[Hebrew] |

| Saturn er den sjette planeten fra solen. |

|

[Norwegian] |

The truth of the proposition that Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun depends only on the physics of the solar system, and not in any obvious way on human convention. By contrast, what these five sentences say does depend partly on human convention. Had English speakers chosen to adopt the word “Saturn” as the name of a different particular planet, the first sentence would have expressed something false. By choosing propositions rather than sentences as the bearers of truth-values, this relativity to human conventions does not apply to truth, a point that many philosophers would consider to be a virtue in a theory of truth.

Propositions are abstract entities; they do not exist in space and time. They are sometimes said to be “timeless”, “eternal”, or “omnitemporal” entities. Terminology aside, the essential point is that propositions are not concrete (or material) objects. Nor, for that matter, are they mental entities; they are not “thoughts” as Frege had suggested in the nineteenth century. The theory that propositions are the bearers of truth-values also has been criticized. Nominalists object to the abstract character of propositions. Another complaint is that it’s not sufficiently clear when we have a case of the same propositions as opposed to similar propositions. This is much like the complaint that we can’t determine when two sentences have exactly the same meaning. The relationship between sentences and propositions is a serious philosophical problem.

Because it is the more favored theory, and for the sake of expediency and consistency, the theory that propositions – and not sentences – are the bearers of truth-values will be adopted in this article. When we speak below of “truths”, we are referring to true propositions. But it should be pointed out that virtually all the claims made below have counterparts in nominalistic theories which reject propositions.

b. Constraints on Truth and Falsehood

There are two commonly accepted constraints on truth and falsehood:

| Every proposition is true or false. |

|

[Law of the Excluded Middle.] |

| No proposition is both true and false. |

|

[Law of Non-contradiction.] |

These constraints require that every proposition has exactly one truth-value. Although the point is controversial, most philosophers add the further constraint that a proposition never changes its truth-value in space or time. Consequently, to say “The proposition that it’s raining was true yesterday but false today” is to equivocate and not actually refer to just one proposition. Similarly, when someone at noon on January 15, 2000 in Vancouver says that the proposition that it is raining is true in Vancouver while false in Sacramento, that person is really talking of two different propositions: (i) that it rains in Vancouver at noon on January 15, 2000 and (ii) that it rains in Sacramento at noon on January 15, 2000. The person is saying proposition (i) is true and (ii) is false.

c. Which Sentences Express Propositions?

Not all sentences express propositions. The interrogative sentence “Who won the World Series in 1951?” does not; neither does the imperative sentence “Please close the window.” Declarative (that is, indicative) sentences – rather than interrogative or imperative sentences – typically are used to express propositions.

d. Problem Cases

But do all declarative sentences express propositions? The following four kinds of declarative sentences have been suggested as not being typically used to express propositions, but all these suggestions are controversial.

1. Sentences containing non-referring expressions

In light of the fact that France has no king, Strawson argued that the sentence, “The present king of France is bald”, fails to express a proposition. In a famous dispute, Russell disagreed with Strawson, arguing that the sentence does express a proposition, and more exactly, a false one.

2. Predictions of future events

What about declarative sentences that refer to events in the future? For example, does the sentence “There will be a sea battle tomorrow” express a proposition? Presumably, today we do not know whether there will be such a battle. Because of this, some philosophers (including Aristotle who toyed with the idea) have argued that the sentence, at the present moment, does not express anything that is now either true or false. Another, perhaps more powerful, motivation for adopting this view is the belief that if sentences involving future human actions were to express propositions, that is, were to express something that is now true or false, then humans would be determined to perform those actions and so humans would have no free will. To defend free will, these philosophers have argued, we must deny truth-values to predictions.

This complicating restriction – that sentences about the future do not now express anything true or false – has been attacked by Quine and others. These critics argue that the restriction upsets the logic we use to reason with such predictions. For example, here is a deductively valid argument involving predictions:

We’ve learned there will be a run on the bank tomorrow.

If there will be a run on the bank tomorrow, then the CEO should be awakened.

So, the CEO should be awakened.

Without assertions in this argument having truth-values, regardless of whether we know those values, we could not assess the argument using the canons of deductive validity and invalidity. We would have to say – contrary to deeply-rooted philosophical intuitions – that it is not really an argument at all. (For another sort of rebuttal to the claim that propositions about the future cannot be true prior to the occurrence of the events described, see Logical Determinism.)

3. Liar Sentences

“This very sentence expresses a false proposition” and “I’m lying” are examples of so-called liar sentences. A liar sentence can be used to generate a paradox when we consider what truth-value to assign it. As a way out of paradox, Kripke suggests that a liar sentence is one of those rare declarative sentences that does not express a proposition. The sentence falls into the truth-value gap. See the article Liar Paradox.

4. Sentences that state moral, ethical, or aesthetic values

Finally, we mention the so-called “fact/value distinction.” Throughout history, moral philosophers have wrestled with the issue of moral realism. Do sentences such as “Torturing children is wrong” – which assert moral principles – assert something true (or false), or do they merely express (in a disguised fashion) the speaker’s opinions, or feelings or values? Making the latter choice, some philosophers argue that these declarative sentences do not express propositions.

3. Correspondence Theory

We return to the principal question, “What is truth?” Truth is presumably what valid reasoning preserves. It is the goal of scientific inquiry, historical research, and business audits. We understand much of what a sentence means by understanding the conditions under which what it expresses is true. Yet the exact nature of truth itself is not wholly revealed by these remarks.

Historically, the most popular theory of truth was the Correspondence Theory. First proposed in a vague form by Plato and by Aristotle in his Metaphysics, this realist theory says truth is what propositions have by corresponding to a way the world is. The theory says that a proposition is true provided there exists a fact corresponding to it. In other words, for any proposition p,

p is true if and only if p corresponds to a fact.

The theory’s answer to the question, “What is truth?” is that truth is a certain relationship—the relationship that holds between a proposition and its corresponding fact. Perhaps an analysis of the relationship will reveal what all the truths have in common.

Consider the proposition that snow is white. Remarking that the proposition’s truth is its corresponding to the fact that snow is white leads critics to request an acceptable analysis of this notion of correspondence. Surely the correspondence is not a word by word connecting of a sentence to its reference. It is some sort of exotic relationship between, say, whole propositions and facts. In presenting his theory of logical atomism early in the twentieth century, Russell tried to show how a true proposition and its corresponding fact share the same structure. Inspired by the notion that Egyptian hieroglyphs are stylized pictures, his student Wittgenstein said the relationship is that of a “picturing” of facts by propositions, but his development of this suggestive remark in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus did not satisfy many other philosophers, nor after awhile, even Wittgenstein himself.

And what are facts? The notion of a fact as some sort of ontological entity was first stated explicitly in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Correspondence Theory does permit facts to be mind-dependent entities. McTaggart, and perhaps Kant, held such Correspondence Theories. The Correspondence theories of Russell, Wittgenstein and Austin all consider facts to be mind-independent. But regardless of their mind-dependence or mind-independence, the theory must provide answers to questions of the following sort. “Canada is north of the U.S.” can’t be a fact. A true proposition can’t be a fact if it also states a fact, so what is the ontological standing of a fact? Is the fact that corresponds to “Brutus stabbed Caesar” the same fact that corresponds to “Caesar was stabbed by Brutus”, or is it a different fact? It might be argued that they must be different facts because one expresses the relationship of stabbing but the other expresses the relationship of being stabbed, which is different. In addition to the specific fact that ball 1 is on the pool table and the specific fact that ball 2 is on the pool table, and so forth, is there the specific fact that there are fewer than 1,006,455 balls on the table? Is there the general fact that many balls are on the table? Does the existence of general facts require there to be the Forms of Plato or Aristotle? What about the negative proposition that there are no pink elephants on the table? Does it correspond to the same situation in the world that makes there be no green elephants on the table? The same pool table must involve a great many different facts. These questions illustrate the difficulty in counting facts and distinguishing them. The difficulty is well recognized by advocates of the Correspondence Theory, but critics complain that characterizations of facts too often circle back ultimately to saying facts are whatever true propositions must correspond to in order to be true. Davidson has criticized the notion of fact, arguing that “if true statements correspond to anything, they all correspond to the same thing” (in “True to the Facts”, Davidson [1984]). Davidson also has argued that facts really are the true statements themselves; facts are not named by them, as the Correspondence Theory mistakenly supposes.

Defenders of the Correspondence Theory have responded to these criticisms in a variety of ways. Sense can be made of the term “correspondence”, some say, because speaking of propositions corresponding to facts is merely making the general claim that summarizes the remark that

(i) The sentence, “Snow is white”, means that snow is white, and (ii) snow actually is white,

and so on for all the other propositions. Therefore, the Correspondence theory must contain a theory of “means that” but otherwise is not at fault. Other defenders of the Correspondence Theory attack Davidson’s identification of facts with true propositions. Snow is a constituent of the fact that snow is white, but snow is not a constituent of a linguistic entity, so facts and true statements are different kinds of entities.

Recent work in possible world semantics has identified facts with sets of possible worlds. The fact that the cat is on the mat contains the possible world in which the cat is on the mat and Adolf Hitler converted to Judaism while Chancellor of Germany. The motive for this identification is that, if sets of possible worlds are metaphysically legitimate and precisely describable, then so are facts.

4. Tarski’s Semantic Theory

To more rigorously describe what is involved in understanding truth and defining it, Alfred Tarski created his Semantic Theory of Truth. In Tarski’s theory, however, talk of correspondence and of facts is eliminated. (Although in early versions of his theory, Tarski did use the term “correspondence” in trying to explain his theory, he later regretted having done so, and dropped the term altogether since it plays no role within his theory.) The Semantic Theory is the successor to the Correspondence Theory.

To more rigorously describe what is involved in understanding truth and defining it, Alfred Tarski created his Semantic Theory of Truth. In Tarski’s theory, however, talk of correspondence and of facts is eliminated. (Although in early versions of his theory, Tarski did use the term “correspondence” in trying to explain his theory, he later regretted having done so, and dropped the term altogether since it plays no role within his theory.) The Semantic Theory is the successor to the Correspondence Theory.

For an illustration of the theory, consider the German sentence “Schnee ist weiss” which means that snow is white. Tarski asks for the truth-conditions of the proposition expressed by that sentence: “Under what conditions is that proposition true?” Put another way: “How shall we complete the following in English: ‘The proposition expressed by the German sentence “Schnee ist weiss” is true …’?” His answer:

|

T: |

|

The proposition expressed by the German sentence “Schnee ist weiss” is true if and only if snow is white. |

We can rewrite Tarski’s T-condition on three lines:

- The proposition expressed by the German sentence “Schnee ist weiss” is true

- if and only if

- snow is white

Line 1 is about truth. Line 3 is not about truth – it asserts a claim about the nature of the world. Thus T makes a substantive claim. Moreover, it avoids the main problems of the earlier Correspondence Theories in that the terms “fact” and “correspondence” play no role whatever.

A theory is a Tarskian truth theory for language L if and only if, for each sentence S of L, if S expresses the proposition that p, then the theory entails a true “T-proposition” of the bi-conditional form:

|

(T) |

|

The proposition expressed by S-in-L is true, if and only if p. |

In the example we have been using, namely, “Schnee ist weiss”, it is quite clear that the T-proposition consists of a containing (or “outer”) sentence in English, and a contained (or “inner” or quoted) sentence in German:

|

T: |

|

The proposition expressed by the German sentence “Schnee ist weiss” is true if and only if snow is white. |

There are, we see, sentences in two distinct languages involved in this T-proposition. If, however, we switch the inner, or quoted sentence, to an English sentence, e.g. to “Snow is white”, we would then have:

|

T: |

|

The proposition expressed by the English sentence “Snow is white” is true if and only if snow is white. |

In this latter case, it looks as if only one language (English), not two, is involved in expressing the T-proposition. But, according to Tarski’s theory, there are still two languages involved: (i) the language one of whose sentences is being quoted and (ii) the language which attributes truth to the proposition expressed by that quoted sentence. The quoted sentence is said to be an element of the object language, and the outer (or containing) sentence which uses the predicate “true” is in the metalanguage.

Tarski discovered that in order to avoid contradiction in his semantic theory of truth, he had to restrict the object language to a limited portion of the metalanguage. Among other restrictions, it is the metalanguage alone that contains the truth-predicates, “true” and “false”; the object language does not contain truth-predicates.

It is essential to see that Tarski’s T-proposition is not saying:

|

X: |

|

Snow is white if and only if snow is white. |

This latter claim is certainly true (it is a tautology), but it is no significant part of the analysis of the concept of truth – indeed it does not even use the words “true” or “truth”, nor does it involve an object language and a metalanguage. Tarski’s T-condition does both.

a. Extending the Semantic Theory Beyond “Simple” Propositions

Tarski’s complete theory is intended to work for (just about) all propositions, expressed by non-problematic declarative sentences, not just “Snow is white.” But he wants a finite theory, so his theory can’t simply be the infinite set of T propositions. Also, Tarski wants his truth theory to reveal the logical structure within propositions that permits valid reasoning to preserve truth. To do all this, the theory must work for more complex propositions by showing how the truth-values of these complex propositions depend on their parts, such as the truth-values of their constituent propositions. Truth tables show how this is done for the simple language of Propositional Logic (e.g. the complex proposition expressed by “A or B” is true, according to the truth table, if and only if proposition A is true, or proposition B is true, or both are true).

Tarski’s goal is to define truth for even more complex languages. Tarski’s theory does not explain (analyze) when a name denotes an object or when an object falls under a predicate; his theory begins with these as given. He wants what we today call a model theory for quantified predicate logic. His actual theory is very technical. It uses the notion of Gödel numbering, focuses on satisfaction rather than truth, and approaches these via the process of recursion. The idea of using satisfaction treats the truth of a simple proposition such as expressed by “Socrates is mortal” by saying:

If “Socrates” is a name and “is mortal” is a predicate, then “Socrates is mortal” expresses a true proposition if and only if there exists an object x such that “Socrates” refers to x and “is mortal” is satisfied by x.

For Tarski’s formal language of predicate logic, he’d put this more generally as follows:

If “a” is a name and “Q” is a predicate, then “a is Q” expresses a true proposition if and only if there exists an object x such that “a” refers to x and “Q” is satisfied by x.

The idea is to define the predicate “is true” when it is applied to the simplest (that is, the non-complex or atomic) sentences in the object language (a language, see above, which does not, itself, contain the truth-predicate “is true”). The predicate “is true” is a predicate that occurs only in the metalanguage, that is, in the language we use to describe the object language. At the second stage, his theory shows how the truth predicate, when it has been defined for propositions expressed by sentences of a certain degree of grammatical complexity, can be defined for propositions of the next greater degree of complexity.

According to Tarski, his theory applies only to artificial languages – in particular, the classical formal languages of symbolic logic – because our natural languages are vague and unsystematic. Other philosophers – for example, Donald Davidson – have not been as pessimistic as Tarski about analyzing truth for natural languages. Davidson has made progress in extending Tarski’s work to any natural language. Doing so, he says, provides at the same time the central ingredient of a theory of meaning for the language. Davidson develops the original idea Frege stated in his Basic Laws of Arithmetic that the meaning of a declarative sentence is given by certain conditions under which it is true—that meaning is given by truth conditions.

As part of the larger program of research begun by Tarski and Davidson, many logicians, linguists, philosophers, and cognitive scientists, often collaboratively, pursue research programs trying to elucidate the truth-conditions (that is, the “logics” or semantics for) the propositions expressed by such complex sentences as:

|

“It is possible that snow is white.” |

|

[modal propositions] |

|

“Snow is white because sunlight is white.” |

|

[causal propositions] |

|

“If snow were yellow, ice would melt at -4°C.” |

|

[contrary-to-fact conditionals] |

|

“Napoleon believed that snow is white.” |

|

[intentional propositions] |

|

“It is obligatory that one provide care for one’s children.” |

|

[deontological propositions] |

|

etc. |

|

|

Each of these research areas contains its own intriguing problems. All must overcome the difficulties involved with ambiguity, tenses, and indexical phrases.

b. Can the Semantic Theory Account for Necessary Truth?

Many philosophers divide the class of propositions into two mutually exclusive and exhaustive subclasses: namely, propositions that are contingent (that is, those that are neither necessarily-true nor necessarily-false) and those that are noncontingent (that is, those that are necessarily-true or necessarily-false).

On the Semantic Theory of Truth, contingent propositions are those that are true (or false) because of some specific way the world happens to be. For example all of the following propositions are contingent:

|

Snow is white. |

|

Snow is purple. |

|

Canada belongs to the U.N. |

|

It is false that Canada belongs to the U.N. |

The contrasting class of propositions comprises those whose truth (or falsehood, as the case may be) is dependent, according to the Semantic Theory, not on some specific way the world happens to be, but on any way the world happens to be. Imagine the world changed however you like (provided, of course, that its description remains logically consistent). Even under those conditions, the truth-values of the following (noncontingent) propositions will remain unchanged:

|

Truths |

|

Falsehoods |

|

Snow is white or it is false that snow is white. |

|

Snow is white and it is false that snow is white. |

|

All squares are rectangles. |

|

Not all squares are rectangles. |

|

2 + 2 = 4 |

|

2 + 2 = 7 |

However, some philosophers who accept the Semantic Theory of Truth for contingent propositions, reject it for noncontingent ones. They have argued that the truth of noncontingent propositions has a different basis from the truth of contingent ones. The truth of noncontingent propositions comes about, they say—not through their correctly describing the way the world is—but as a matter of the definitions of terms occurring in the sentences expressing those propositions. Noncontingent truths, on this account, are said to be true by definition, or – as it is sometimes said, in a variation of this theme – as a matter of conceptual relationships between the concepts at play within the propositions, or—yet another (kindred) way—as a matter of the meanings of the sentences expressing the propositions.

It is apparent, in this competing account, that one is invoking a kind of theory of linguistic truth. In this alternative theory, truth for a certain class of propositions, namely the class of noncontingent propositions, is to be accounted for – not in their describing the way the world is, but rather – because of certain features of our human linguistic constructs.

c. The Linguistic Theory of Necessary Truth

Does the Semantic Theory need to be supplemented in this manner? If one were to adopt the Semantic Theory of Truth, would one also need to adopt a complementary theory of truth, namely, a theory of linguistic truth (for noncontingent propositions)? Or, can the Semantic Theory of Truth be used to explain the truth-values of all propositions, the contingent and noncontingent alike? If so, how?

To see how one can argue that the Semantic Theory of Truth can be used to explicate the truth of noncontingent propositions, consider the following series of propositions, the first four of which are contingent, the fifth of which is noncontingent:

- There are fewer than seven bumblebees or more than ten.

- There are fewer than eight bumblebees or more than ten.

- There are fewer than nine bumblebees or more than ten.

- There are fewer than ten bumblebees or more than ten.

- There are fewer than eleven bumblebees or more than ten.

Each of these propositions, as we move from the second to the fifth, is slightly less specific than its predecessor. Each can be regarded as being true under a greater range of variation (or circumstances) than its predecessor. When we reach the fifth member of the series we have a proposition that is true under any and all sets of circumstances. (Some philosophers – a few in the seventeenth century, a very great many more after the mid-twentieth century – use the idiom of “possible worlds”, saying that noncontingent truths are true in all possible worlds [that is, under any logically possible circumstances].) On this view, what distinguishes noncontingent truths from contingent ones is not that their truth arises as a consequence of facts about our language or of meanings, etc.; but that their truth has to do with the scope (or number) of possible circumstances under which the proposition is true. Contingent propositions are true in some, but not all, possible circumstances (or possible worlds). Noncontingent propositions, in contrast, are true in all possible circumstances or in none. There is no difference as to the nature of truth for the two classes of propositions, only in the ranges of possibilities in which the propositions are true.

An adherent of the Semantic Theory will allow that there is, to be sure, a powerful insight in the theories of linguistic truth. But, they will counter, these linguistic theories are really shedding no light on the nature of truth itself. Rather, they are calling attention to how we often go about ascertaining the truth of noncontingent propositions. While it is certainly possible to ascertain the truth experientially (and inductively) of the noncontingent proposition that all aunts are females – for example, one could knock on a great many doors asking if any of the residents were aunts and if so, whether they were female – it would be a needless exercise. We need not examine the world carefully to figure out the truth-value of the proposition that all aunts are females. We might, for example, simply consult an English dictionary. How we ascertain, find out, determine the truth-values of noncontingent propositions may (but need not invariably) be by nonexperiential means; but from that it does not follow that the nature of truth of noncontingent propositions is fundamentally different from that of contingent ones.

On this latter view, the Semantic Theory of Truth is adequate for both contingent propositions and noncontingent ones. In neither case is the Semantic Theory of Truth intended to be a theory of how we might go about finding out what the truth-value is of any specified proposition. Indeed, one very important consequence of the Semantic Theory of Truth is that it allows for the existence of propositions whose truth-values are in principle unknowable to human beings.

And there is a second motivation for promoting the Semantic Theory of Truth for noncontingent propositions. How is it that mathematics is able to be used (in concert with physical theories) to explain the nature of the world? On the Semantic Theory, the answer is that the noncontingent truths of mathematics correctly describe the world (as they would any and every possible world). The Linguistic Theory, which makes the truth of the noncontingent truths of mathematics arise out of features of language, is usually thought to have great, if not insurmountable, difficulties in grappling with this question.

5. Coherence Theories

The Correspondence Theory and the Semantic Theory account for the truth of a proposition as arising out of a relationship between that proposition and features or events in the world. Coherence Theories (of which there are a number), in contrast, account for the truth of a proposition as arising out of a relationship between that proposition and other propositions.

Coherence Theories are valuable because they help to reveal how we arrive at our truth claims, our knowledge. We continually work at fitting our beliefs together into a coherent system. For example, when a drunk driver says, “There are pink elephants dancing on the highway in front of us”, we assess whether his assertion is true by considering what other beliefs we have already accepted as true, namely,

- Elephants are gray.

- This locale is not the habitat of elephants.

- There is neither a zoo nor a circus anywhere nearby.

- Severely intoxicated persons have been known to experience hallucinations.

But perhaps the most important reason for rejecting the drunk’s claim is this:

- Everyone else in the area claims not to see any pink elephants.

In short, the drunk’s claim fails to cohere with a great many other claims that we believe and have good reason not to abandon. We, then, reject the drunk’s claim as being false (and take away the car keys).

Specifically, a Coherence Theory of Truth will claim that a proposition is true if and only if it coheres with ___. For example, one Coherence Theory fills this blank with “the beliefs of the majority of persons in one’s society”. Another fills the blank with “one’s own beliefs”, and yet another fills it with “the beliefs of the intellectuals in one’s society”. The major coherence theories view coherence as requiring at least logical consistency. Rationalist metaphysicians would claim that a proposition is true if and only if it “is consistent with all other true propositions”. Some rationalist metaphysicians go a step beyond logical consistency and claim that a proposition is true if and only if it “entails (or logically implies) all other true propositions”. Leibniz, Spinoza, Hegel, Bradley, Blanshard, Neurath, Hempel (late in his life), Dummett, and Putnam have advocated Coherence Theories of truth.

Coherence Theories have their critics too. The proposition that bismuth has a higher melting point than tin may cohere with my beliefs but not with your beliefs. This, then, leads to the proposition being both “true for me” but “false for you”. But if “true for me” means “true” and “false for you” means “false” as the Coherence Theory implies, then we have a violation of the law of non-contradiction, which plays havoc with logic. Most philosophers prefer to preserve the law of non-contradiction over any theory of truth that requires rejecting it. Consequently, if someone is making a sensible remark by saying, “That is true for me but not for you,” then the person must mean simply, “I believe it, but you do not.” Truth is not relative in the sense that something can be true for you but not for me.

A second difficulty with Coherence Theories is that the beliefs of any one person (or of any group) are invariably self-contradictory. A person might, for example, believe both “Absence makes the heart grow fonder” and “Out of sight, out of mind.” But under the main interpretation of “cohere”, nothing can cohere with an inconsistent set. Thus most propositions, by failing to cohere, will not have truth-values. This result violates the law of the excluded middle.

And there is a third objection. What does “coheres with” mean? For X to “cohere with” Y, at the very least X must be consistent with Y. All right, then, what does “consistent with” mean? It would be circular to say that “X is consistent with Y” means “it is possible for X and Y both to be true together” because this response is presupposing the very concept of truth that it is supposed to be analyzing.

Some defenders of the Coherence Theory will respond that “coheres with” means instead “is harmonious with”. Opponents, however, are pessimistic about the prospects for explicating the concept “is harmonious with” without at some point or other having to invoke the concept of joint truth.

A fourth objection is that Coherence theories focus on the nature of verifiability and not truth. They focus on the holistic character of verifying that a proposition is true but don’t answer the principal problem, “What is truth itself?”

a. Postmodernism: The Most Recent Coherence Theory

In recent years, one particular Coherence Theory has attracted a lot of attention and some considerable heat and fury. Postmodernist philosophers ask us to carefully consider how the statements of the most persuasive or politically influential people become accepted as the “common truths”. Although everyone would agree that influential people – the movers and shakers – have profound effects upon the beliefs of other persons, the controversy revolves around whether the acceptance by others of their beliefs is wholly a matter of their personal or institutional prominence. The most radical postmodernists do not distinguish acceptance as true from being true; they claim that the social negotiations among influential people “construct” the truth. The truth, they argue, is not something lying outside of human collective decisions; it is not, in particular, a “reflection” of an objective reality. Or, to put it another way, to the extent that there is an objective reality it is nothing more nor less than what we say it is. We human beings are, then, the ultimate arbiters of what is true. Consensus is truth. The “subjective” and the “objective” are rolled into one inseparable compound.

These postmodernist views have received a more sympathetic reception among social scientists than among physical scientists. Social scientists will more easily agree, for example, that the proposition that human beings have a superego is a “construction” of (certain) politically influential psychologists, and that as a result, it is (to be regarded as) true. In contrast, physical scientists are – for the most part – rather unwilling to regard propositions in their own field as somehow merely the product of consensus among eminent physical scientists. They are inclined to believe that the proposition that protons are composed of three quarks is true (or false) depending on whether (or not) it accurately describes an objective reality. They are disinclined to believe that the truth of such a proposition arises out of the pronouncements of eminent physical scientists. In short, physical scientists do not believe that prestige and social influence trump reality.

6. Pragmatic Theories

A Pragmatic Theory of Truth holds (roughly) that a proposition is true if it is useful to believe. Peirce and James were its principal advocates. Utility is the essential mark of truth. Beliefs that lead to the best “payoff”, that are the best justification of our actions, that promote success, are truths, according to the pragmatists.

The problems with Pragmatic accounts of truth are counterparts to the problems seen above with Coherence Theories of truth.

First, it may be useful for someone to believe a proposition but also useful for someone else to disbelieve it. For example, Freud said that many people, in order to avoid despair, need to believe there is a god who keeps a watchful eye on everyone. According to one version of the Pragmatic Theory, that proposition is true. However, it may not be useful for other persons to believe that same proposition. They would be crushed if they believed that there is a god who keeps a watchful eye on everyone. Thus, by symmetry of argument, that proposition is false. In this way, the Pragmatic theory leads to a violation of the law of non-contradiction, say its critics.

Second, certain beliefs are undeniably useful, even though – on other criteria – they are judged to be objectively false. For example, it can be useful for some persons to believe that they live in a world surrounded by people who love or care for them. According to this criticism, the Pragmatic Theory of Truth overestimates the strength of the connection between truth and usefulness.

Truth is what an ideally rational inquirer would in the long run come to believe, say some pragmatists. Truth is the ideal outcome of rational inquiry. The criticism that we don’t now know what happens in the long run merely shows we have a problem with knowledge, but it doesn’t show that the meaning of “true” doesn’t now involve hindsight from the perspective of the future. Yet, as a theory of truth, does this reveal what “true” means?

7. Deflationary Theories

What all the theories of truth discussed so far have in common is the assumption that a proposition is true just in case the proposition has some property or other – correspondence with the facts, satisfaction, coherence, utility, etc. Deflationary theories deny this assumption.

a. Redundancy Theory

The principal deflationary theory is the Redundancy Theory advocated by Frege, Ramsey, and Horwich. Frege expressed the idea this way:

It is worthy of notice that the sentence “I smell the scent of violets” has the same content as the sentence “It is true that I smell the scent of violets.” So it seems, then, that nothing is added to the thought by my ascribing to it the property of truth. (Frege, 1918)

When we assert a proposition explicitly, such as when we say “I smell the scent of violets”, then saying “It’s true that I smell the scent of violets” would be redundant; it would add nothing because the two have the same meaning. Today’s more minimalist advocates of the Redundancy Theory retreat from this remark about meaning and say merely that the two are necessarily equivalent.

Where the concept of truth really pays off is when we do not, or can not, assert a proposition explicitly, but have to deal with an indirect reference to it. For instance, if we wish to say, “What he will say tomorrow is true”, we need the truth predicate “is true”. Admittedly the proposition is an indirect way of saying, “If he says tomorrow that it will snow, then it will snow; if he says tomorrow that it will rain, then it will rain; if he says tomorrow that 7 + 5 = 12, then 7 + 5 = 12; and so forth.” But the phrase “is true” cannot be eliminated from “What he will say tomorrow is true” without producing an unacceptable infinite conjunction. The truth predicate “is true” allows us to generalize and say things more succinctly (indeed to make those claims with only a finite number of utterances). In short, the Redundancy Theory may work for certain cases, say its critics, but it is not generalizable to all; there remain recalcitrant cases where “is true” is not redundant.

Advocates of the Redundancy Theory respond that their theory recognizes the essential point about needing the concept of truth for indirect reference. The theory says that this is all that the concept of truth is needed for, and that otherwise its use is redundant.

b. Performative Theory

The Performative Theory is a deflationary theory that is not a redundancy theory. It was advocated by Strawson who believed Tarski’s Semantic Theory of Truth was basically mistaken.

The Performative Theory of Truth argues that ascribing truth to a proposition is not really characterizing the proposition itself, nor is it saying something redundant. Rather, it is telling us something about the speaker’s intentions. The speaker – through his or her agreeing with it, endorsing it, praising it, accepting it, or perhaps conceding it – is licensing our adoption of (the belief in) the proposition. Instead of saying, “It is true that snow is white”, one could substitute “I embrace the claim that snow is white.” The key idea is that saying of some proposition, P, that it is true is to say in a disguised fashion “I commend P to you”, or “I endorse P”, or something of the sort.

The case may be likened somewhat to that of promising. When you promise to pay your sister five dollars, you are not making a claim about the proposition expressed by “I will pay you five dollars”; rather you are performing the action of promising her something. Similarly, according to the Performative Theory of Truth, when you say “It is true that Vancouver is north of Sacramento”, you are performing the act of giving your listener license to believe (and to act upon the belief) that Vancouver is north of Sacramento.

Critics of the Performative Theory charge that it requires too radical a revision in our logic. Arguments have premises that are true or false, but we don’t consider premises to be actions, says Geach. Other critics complain that, if all the ascription of “is true” is doing is gesturing consent, as Strawson believes, then, when we say

“Please shut the door” is true,

we would be consenting to the door’s being shut. Because that is absurd, says Huw Price, something is wrong with Strawson’s Performative Theory.

c. Prosentential Theory

The Prosentential Theory of Truth suggests that the grammatical predicate “is true” does not function semantically or logically as a predicate. All uses of “is true” are prosentential uses. When someone asserts “It’s true that it is snowing”, the person is asking the hearer to consider the sentence “It is snowing” and is saying “That is true” where the remark “That is true” is taken holistically as a prosentence, in analogy to a pronoun. A pronoun such as “she” is a substitute for the name of the person being referred to. Similarly, “That is true” is a substitute for the proposition being considered. Likewise, for the expression “It is true.” According to the Prosentential Theory, all uses of “true” can be reduced to uses either of “That is true” or “It is true” or variants of these with other tenses. Because these latter prosentential uses of the word “true” cannot be eliminated from our language during analysis, the Prosentential Theory is not a redundancy theory.

Critics of the theory remark that it can give no account of what is common to all our uses of the word “true,” such as those in the unanalyzed operators “it-will-be-true-that” and “it-is-true-that” and “it-was-true-that”.

8. Related Issues

a. Beyond Truth to Knowledge

For generations, discussions of truth have been bedeviled by the question, “How could a proposition be true unless we know it to be true?” Aristotle’s famous worry was that contingent propositions about the future, such as “There will be a sea battle tomorrow”, couldn’t be true now, for fear that this would deny free will to the sailors involved. Advocates of the Correspondence Theory and the Semantic Theory have argued that a proposition need not be known in order to be true. Truth, they say, arises out of a relationship between a proposition and the way the world is. No one need know that that relationship holds, nor – for that matter – need there even be any conscious or language-using creatures for that relationship to obtain. In short, truth is an objective feature of a proposition, not a subjective one.

For a true proposition to be known, it must (at the very least) be a justified belief. Justification, unlike truth itself, requires a special relationship among propositions. For a proposition to be justified it must, at the very least, cohere with other propositions that one has adopted. On this account, coherence among propositions plays a critical role in the theory of knowledge. Nevertheless it plays no role in a theory of truth, according to advocates of the Correspondence and Semantic Theories of Truth.

Finally, should coherence – which plays such a central role in theories of knowledge – be regarded as an objective relationship or as a subjective one? Not surprisingly, theorists have answered this latter question in divergent ways. But the pursuit of that issue takes one beyond the theories of truth.

b. Algorithms for Truth

An account of what “true” means does not have to tell us what is true, nor tell us how we could find out what is true. Similarly, an account of what “bachelor” means should not have to tell us who is a bachelor, nor should it have to tell us how we could find out who is. However, it would be fascinating if we could discover a way to tell, for any proposition, whether it is true.

Perhaps some machine could do this, philosophers have speculated. For any formal language, we know in principle how to generate all the sentences of that language. If we were to build a machine that produces one by one all the many sentences, then eventually all those that express truths would be produced. Unfortunately, along with them, we would also generate all those that express false propositions. We also know how to build a machine that will generate only sentences that express truths. For example, we might program a computer to generate “1 + 1 is not 3”, then “1 + 1 is not 4”, then “1 + 1 is not 5”, and so forth. However, to generate all and only those sentences that express truths is quite another matter.

Leibniz (1646-1716) dreamed of achieving this goal. By mechanizing deductive reasoning he hoped to build a machine that would generate all and only truths. As he put it, “How much better will it be to bring under mathematical laws human reasoning which is the most excellent and useful thing we have.” This would enable one’s mind to “be freed from having to think directly of things themselves, and yet everything will turn out correct.” His actual achievements were disappointing in this regard, but his dream inspired many later investigators.

Some progress on the general problem of capturing all and only those sentences which express true propositions can be made by limiting the focus to a specific domain. For instance, perhaps we can find some procedure that will produce all and only the truths of arithmetic, or of chemistry, or of Egyptian political history. Here, the key to progress is to appreciate that universal and probabilistic truths “capture” or “contain” many more specific truths. If we know the universal and probabilistic laws of quantum mechanics, then (some philosophers have argued) we thereby indirectly (are in a position to) know the more specific scientific laws about chemical bonding. Similarly, if we can axiomatize an area of mathematics, then we indirectly have captured the infinitely many specific theorems that could be derived from those axioms, and we can hope to find a decision procedure for the truths, a procedure that will guarantee a correct answer to the question, “Is that true?”

Significant progress was made in the early twentieth century on the problem of axiomatizing arithmetic and other areas of mathematics. Let’s consider arithmetic. In the 1920s, David Hilbert hoped to represent the sentences of arithmetic very precisely in a formal language, then to generate all and only the theorems of arithmetic from uncontroversial axioms, and thereby to show that all true propositions of arithmetic can in principle be proved as theorems. This would put the concept of truth in arithmetic on a very solid basis. The axioms would “capture” all and only the truths. However, Hilbert’s hopes would soon be dashed. In 1931, Kurt Gödel (1906-1978), in his First Incompleteness Theorem, proved that any classical self-consistent formal language capable of expressing arithmetic must also contain sentences of arithmetic that cannot be derived within that system, and hence that the propositions expressed by those sentences could not be proven true (or false) within that system. Thus the concept of truth transcends the concept of proof in classical formal languages. This is a remarkable, precise insight into the nature of truth.

c. Can “is true” be Eliminated?

Can “is true” be defined so that it can be replaced by its definition? Unfortunately for the clarity of this question, there is no one concept of “definition”. A very great many linguistic devices count as definitions. These devices include providing a synonym, offering examples, pointing at objects that satisfy the term being defined, using the term in sentences, contrasting it with opposites, and contrasting it with terms with which it is often confused. (For further reading, see Definitions, Dictionaries, and Meanings.)

However, modern theories about definition have not been especially recognized, let alone adopted, outside of certain academic and specialist circles. Many persons persist with the earlier, naive, view that the role of a definition is only to offer a synonym for the term to be defined. These persons have in mind such examples as: “ ‘hypostatize’ means (or, is a synonym for) ‘reify’

‘hypostatize’ means (or, is a synonym for) ‘reify’ “.

“.

If one were to adopt this older view of definition, one might be inclined to demand of a theory of truth that it provide a definition of “is true” which permitted its elimination in all contexts in the language. Tarski was the first person to show clearly that there could never be such a strict definition for “is true” in its own language. The definition would allow for a line of reasoning that produced the Liar Paradox (recall above) and thus would lead us into self contradiction. (See the discussion, in the article The Liar Paradox, of Tarski’s Udefinability Theorem of 1936.)

Kripke has attempted to avoid this theorem by using only a “partial” truth-predicate so that not every sentence has a truth-value. In effect, Kripke’s “repair” permits a definition of the truth-predicate within its own language but at the expense of allowing certain violations of the law of excluded middle.

d. Can a Theory of Truth Avoid Paradox?

The brief answer is, “Not if it contains its own concept of truth.” If the language is made precise by being formalized, and if it contains its own so-called global truth predicate, then Tarski has shown that the language will enable us to reason our way to a contradiction. That result shows that we do not have a coherent concept of truth (for a language within that language). Some of our beliefs about truth, and about related concepts that are used in the argument to the contradiction, must be rejected, even though they might seem to be intuitively acceptable.

There is no reason to believe that paradox is to be avoided by rejecting formal languages in favor of natural languages. The Liar Paradox first appeared in natural languages. And there are other paradoxes of truth, such as Löb’s Paradox, which follow from principles that are acceptable in either formal or natural languages, namely the principles of modus ponens and conditional proof.

The best solutions to the paradoxes use a similar methodology, the “systematic approach”. That is, they try to remove vagueness and be precise about the ramifications of their solutions, usually by showing how they work in a formal language that has the essential features of our natural language. The Liar Paradox and Löb’s Paradox represent a serious challenge to understanding the logic of our natural language. The principal solutions agree that – to resolve a paradox – we must go back and systematically reform or clarify some of our original beliefs. For example, the solution may require us to revise the meaning of “is true”. However, to be acceptable, the solution must be presented systematically and be backed up by an argument about the general character of our language. In short, there must be both systematic evasion and systematic explanation. Also, when it comes to developing this systematic approach, the goal of establishing a coherent basis for a consistent semantics of natural language is much more important than the goal of explaining the naive way most speakers use the terms “true” and “not true”. The later Wittgenstein did not agree. He rejected the systematic approach and elevated the need to preserve ordinary language, and our intuitions about it, over the need to create a coherent and consistent semantical theory.

e. Is The Goal of Scientific Research to Achieve Truth?

Except in special cases, most scientific researchers would agree that their results are only approximately true. Nevertheless, to make sense of this, philosophers need adopt no special concept such as “approximate truth.” Instead, it suffices to say that the researchers’ goal is to achieve truth, but they achieve this goal only approximately, or only to some approximation.

Other philosophers believe it’s a mistake to say the researchers’ goal is to achieve truth. These “scientific anti-realists” recommend saying that research in, for example, physics, economics, and meteorology, aims only for usefulness. When they aren’t overtly identifying truth with usefulness, the instrumentalists Peirce, James and Schlick take this anti-realist route, as does Kuhn. They would say atomic theory isn’t true or false but rather is useful for predicting outcomes of experiments and for explaining current data. Giere recommends saying science aims for the best available “representation”, in the same sense that maps are representations of the landscape. Maps aren’t true; rather, they fit to a better or worse degree. Similarly, scientific theories are designed to fit the world. Scientists should not aim to create true theories; they should aim to construct theories whose models are representations of the world.

9. References and Further Reading

- Bradley, Raymond and Norman Swartz . Possible Worlds: an Introduction to Logic and Its Philosophy, Hackett Publishing Company, 1979.

- Davidson, Donald. Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation, Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Davidson, Donald. “The Structure and Content of Truth”, The Journal of Philosophy, 87 (1990), 279-328.

- Horwich, Paul. Truth, Basil Blackwell Ltd., 1990.

- Mates, Benson. “Two Antinomies”, in Skeptical Essays, The University of Chicago Press, 1981, 15-57.

- McGee, Vann. Truth, Vagueness, and Paradox: An Essay on the Logic of Truth, Hackett Publishing, 1991.

- Kirkham, Richard. Theories of Truth: A Critical Introduction, MIT Press, 1992.

- Kripke, Saul. “Outline of a Theory of Truth”, Journal of Philosophy, 72 (1975), 690-716.

- Quine, W. V. “Truth”, in Quiddities: An Intermittently Philosophical Dictionary, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Ramsey, F. P. “Facts and Propositions”, in Proceedings of the Arisotelian Society, Supplement, 7, 1927.

- Russell, B. The Problems of Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 1912.

- Strawson, P. F. “Truth”, in Analysis, vol. 9, no. 6, 1949.

- Tarski, Alfred, “The Semantic Conception of Truth and the Foundations of Semantics”, in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 4 (1944).

- Tarski, Alfred. “The Concept of Truth in Formalized Languages”, in Logic, Semantics, Metamathematics, Clarendon Press, 1956.

Author Information

Bradley Dowden

Email: dowden@csus.edu

California State University Sacramento

U. S. A.

Norman Swartz

Email: swartz@sfu.ca

Simon Fraser University

Canada

Alfred Schutz philosophized about social science in a broad signification of the word. He was deeply respectful of actual scientific practice, and produced a classification of the sciences; explicated methodological postulates for empirical science in general and the social sciences specifically; and clarified basic concepts for interpretative sociology in particular. His work shows how philosophy of the cultural sciences can be done phenomenologically.

Alfred Schutz philosophized about social science in a broad signification of the word. He was deeply respectful of actual scientific practice, and produced a classification of the sciences; explicated methodological postulates for empirical science in general and the social sciences specifically; and clarified basic concepts for interpretative sociology in particular. His work shows how philosophy of the cultural sciences can be done phenomenologically.

Perception

Perception

Although J. C. F. Hölderlin has, since the beginning of the twentieth century, enjoyed the reputation of being one of Germany’s greatest poets, his recognition as an important philosophical figure is more recent. The revival of an interest in

Although J. C. F. Hölderlin has, since the beginning of the twentieth century, enjoyed the reputation of being one of Germany’s greatest poets, his recognition as an important philosophical figure is more recent. The revival of an interest in  The

The

Time travel is commonly defined with David Lewis’ definition: An object time travels if and only if the difference between its departure and arrival times as measured in the surrounding world does not equal the duration of the journey undergone by the object. For example, Jane is a time traveler if she travels away from home in her spaceship for one hour as measured by her own clock on the ship but travels two hours as measured by the clock back home, assuming both clocks are functioning properly.

Time travel is commonly defined with David Lewis’ definition: An object time travels if and only if the difference between its departure and arrival times as measured in the surrounding world does not equal the duration of the journey undergone by the object. For example, Jane is a time traveler if she travels away from home in her spaceship for one hour as measured by her own clock on the ship but travels two hours as measured by the clock back home, assuming both clocks are functioning properly.

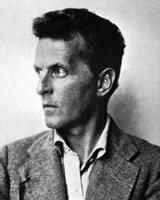

Ludwig Wittgenstein is one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century, and regarded by some as the most important since

Ludwig Wittgenstein is one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century, and regarded by some as the most important since