Russian Philosophy

This article provides a historical survey of Russian philosophers and thinkers. It emphasizes Russian epistemological concerns rather than ontological and ethical concerns, hopefully without neglecting or disparaging them. After all, much work in ethics, at least during the Soviet period, strictly supported the state, such that what is taken to be good is often that which helps secure the goals of Soviet society. Unlike most other major nations, political events in Russia’s history played large roles in shaping its periods of philosophical development.

This article provides a historical survey of Russian philosophers and thinkers. It emphasizes Russian epistemological concerns rather than ontological and ethical concerns, hopefully without neglecting or disparaging them. After all, much work in ethics, at least during the Soviet period, strictly supported the state, such that what is taken to be good is often that which helps secure the goals of Soviet society. Unlike most other major nations, political events in Russia’s history played large roles in shaping its periods of philosophical development.

Various conceptions of Russian philosophy have led scholars to locate its start at different moments in history and with different individuals. However, few would dispute that there was a religious orientation to Russian thought prior to Peter the Great (around 1700) and that professional, secular philosophy—in which philosophical issues are considered on their own terms without explicit appeal to their utility—arose comparatively recently in the country’s history.

Despite the difficulties, we can distinguish five major periods in Russian philosophy. In the first period (The Period of Philosophical Remarks), there is a clear emergence of something resembling what we would now characterize as philosophy. However, religious and political conservativism imposed many restrictions on the dissemination of philosophy during this time. The second period (The Philosophical Dark Age) was marked by much forced silence of the Russian philosophical community. Many subsumed philosophy under the scope of religion or politics, and the discipline was evaluated primarily by whether it was of any utility. The third period (The Emergence of Professional Philosophy) showed an increase in many major Russian thinkers, many of which were influenced by philosophers of the West, such as Plato, Kant, Spinoza, Hegel, and Husserl. The rise of Russian philosophy that was not beholden to religion and politics also began in this period. In the fourth period (The Soviet Era), there were significant concerns about the primacy of the natural sciences. This spawned, for example, the debate between those who thought all philosophical problems would be resolved by the natural sciences (the mechanists) and those who defended the existence of philosophy as a separate discipline (the Deborinists). The fifth period (The Post-Soviet Era) is surely too recent to fully describe. However, there has certainly been a rediscovery of the works of the religious philosophers that were strictly forbidden in the past.

Table of Contents

1. Overview of the Problem

The very notion of Russian philosophy poses a cultural-historical problem. No consensus exists on which works it encompasses and which authors made decisive contributions. To a large degree, a particular ideological conception of Russian philosophy, of what constitutes its essential traits, has driven the choice of inclusions. In turn, the various conceptions have led scholars to locate the start of Russian philosophy at different moments and with different individuals.

a. Masaryk

Among the first to deal with this issue was T. Masaryk (1850-1937), a student of Franz Brentano’s and later the first president of the newly formed Czechoslovakia. Masaryk, following the lead of a pioneering Russian scholar E. Radlov (1854-1928), held that Russian thinkers have historically given short shrift to epistemological issues in favor of ethical and political discussions. For Masaryk, even those who were indebted to the ethical teachings of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), scarcely understood and appreciated his epistemological criticism, which they viewed as essentially subjectivistic. True, Masaryk does comment that the Russian mind is “more inclined” to mythology than the Western European—a position that could lead us to conclude that he viewed the Russian mind as in some way innately different from others. However, he makes clear that the Russian predilection for unequivocal acceptance or total negation of a viewpoint stems, at least to a large degree, from the native Orthodox faith. Church teachings had “accustomed” the Russian mind to accept doctrinaire revelation without criticism. For this reason, Masaryk certainly placed the start of Russian philosophy no earlier than the 19th century with the historiosophical musings of P. Chaadaev (1794-1856), who not surprisingly also pinned blame for the country’s position in world affairs on its Orthodox faith.

b. Lossky and Zenkovsky

Others, particularly ethnic Russians, alarmed by what they took to be Masaryk’s implicit denigration of their intellectual character, have denied that Russian philosophy suffered from a veritable absence of epistemological inquiry. For N. Lossky (1870-1965), Russian philosophers admittedly have, as a rule, sought to relate their investigations, regardless of the specific concern, to ethical problems. This, together with a prevalent epistemological view that externality is knowable—and indeed through an immediate grasping or intuition—has given Russian philosophy a form distinct from much of modern Western philosophy. Nevertheless, the relatively late emergence of independent Russian philosophical thought was a result of the medieval “Tatar yoke” and of the subsequent cultural isolation of Russia until Peter the Great’s opening to the West. Even then, Russian thought remained heavily indebted to developments in Germany until the emergence of 19th century Slavophilism with I. Kireyevsky (1806-56) and A. Khomiakov (1804-60).

Even more emphatically than Lossky, V. Zenkovsky (1881-1962) denied the absence of epistemological inquiry in Russian thought. In his eyes, Russian philosophy rejected the primacy accorded, at least since Kant, to the theory of knowledge over ethical and ontological issues. A widespread, though not unanimous, view among Russian philosophers, according to Zenkovsky, is ontologism (that is, that knowledge plays but a secondary role in human existential affairs). Yet, whereas many Russians historically have advocated such an ontologism, it is by no means unique to that nation. More characteristic of Russian philosophy, for Zenkovsky, is its anthropocentrism (that is, a concern with the human condition and humanity’s ultimate fate). For this reason, philosophy in Russia has historically been expressed in terms noticeably different from those in the West. Furthermore, like Lossky, Zenkovsky saw the comparatively late development of Russian philosophy as a result of the country’s isolation and subsequent infatuation with Western modes of thought until the 19th century. Thus, although Zenkovsky placed Kireyevsky only at the “threshold” of a mature, independent “Russian philosophy” (understood as a system), the former believed it possible to trace the first independent stirrings back to G. Skovoroda (1722-94), who, strictly speaking, was the first Russian philosopher.

Largely as a result of rejecting the primacy of epistemology and the Cartesian model of methodological inquiry, Lossky (and Zenkovsky even more) included within “Russian philosophy” figures whose views would hardly qualify for inclusion within contemporary Western treatises in the history of philosophy. During the Soviet period, Russian scholars appealed to the Marxist doctrine linking intellectual thought to the socio-economic base for their own rather broad notion of philosophy. Any attempt at confining their history to what passes for professionalism today in the West was simply dismissed as “bourgeois.” In this way, such literary figures as Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy were routinely included in texts, though just as routinely condemned for their own supposedly bourgeois mentality. Western studies devoted to the history of Russian philosophy have largely since their emergence acquiesced in this acceptance of a broad understanding of philosophy. F. Copleston, for example, conceded that “for historical reasons” philosophy in Russia tended to be informed by a socio-political orientation. Such an apology for his book-length study can be seen as somewhat self-serving, since he recognizes that philosophy as a theoretical discipline never flourished in Russia. Likewise, A. Walicki fears viewing the history of Russian philosophy from the contemporary Western technical standpoint would result in an impoverished picture populated with wholly unoriginal authors. Obviously, one cannot write a history of some discipline if that discipline lacks content!

c. Shpet

Of those seemingly unafraid to admit the historical poverty of philosophical thought in Russia, Gustav Shpet (1879-1937) stands out not only for his vast historical erudition but also because of his own original philosophical contributions. Shpet, almost defiantly, characterized the intellectual life of Russia as rooted in an “elemental ignorance.” Unlike Masaryk, however, Shpet did not view this dearth as stemming from Russia’s Orthodox faith but from his country’s linguistic isolation. The adopted language of the Bulgars lacked a cultural and intellectual tradition. Without a heritage by which to appreciate ideas, intellectual endeavors were valued for their utility alone. Although the government saw no practical benefit in it, the Church initially found philosophy useful as a weapon to safeguard its position. This toleration extended no further, and certainly the clerical authorities countenanced no divergence or independent creativity. With Peter the Great’s governmental reforms, the state saw the utility of education and championed those and only those disciplines that served a bureaucratic and apologetic function. After the successful military campaign against Napoleon, many young Russian officers had their first experience of Western European culture and returned to Russia with incipient revolutionary ideas that, in a relatively short time, found expression in the abortive Decembrist Uprising of 1825. Finally, towards the end of the 1830s a new group, a “nihilistic intelligentsia,” appeared that preached a toleration of cultural forms, including philosophy, but only insofar as they served the “people.” Such was the fate of philosophy in Russia that it was virtually never viewed as anything but a tool or weapon and had to incessantly demonstrate this utility on fear of losing its legitimacy. Shpet concludes that philosophy as knowledge, as being of value for its own sake, was never given a chance.

d. Concluding Remarks

Regardless of the date from which we place the start of Russian philosophy and its first practitioner—and we will have more to say on this topic as we go—few would dispute the religious orientation of Russian thought prior to Peter the Great and that professional secular philosophy arose comparatively recently in the country’s history. If we are to avoid a double standard, one for “Western” thought and another for Russian, which is not merely self-serving but also condescending, then we must examine the historical record for indisputable instances of philosophical thought that would be recognized as such regardless of where they originated. Although, on the whole, our inclusions, omissions, and evaluations may more closely resemble those of Shpet than, say, Lossky, we thereby need not invoke any metaphysical historical scheme to justify them.

How precisely to subdivide the history of Russian philosophy has also been a subject of some controversy. In his pioneering study from 1898, A. Vvedensky (see below), Russia’s foremost neo-Kantian, found three periods up to his time. Of course, in light of 20th century events his list must be revisited, reexamined, and expanded. We can readily discern five periods in Russian philosophy, the last of which is still too recent to characterize. Unlike most major nations, specific extra-philosophical (namely, political) events clearly played a major role, if not the sole role, in terminating a period.

2. Historical Periods

a. The Period of Philosophical Remarks (c.1755-1825)

Although one can find scattered remarks of a philosophical nature in Russian writings before the mid-eighteenth century, these are at best of marginal interest to the professionally trained philosopher. For the most part, these remarks were not intended to stand as rational arguments in support of a position. Even in the ecclesiastic academies, the thin scholastic veneer of the accepted texts was merely a traditional schematic device, a relic from the time when the only appropriate texts available were Western. For whatever reason, only with the opening of the nation’s first university in Moscow in 1755 do we see the emergence of something resembling philosophy, as we use that term today. Even then, however, the floodgates did not burst wide open. The first occupant of the chair of philosophy, N. Popovsky (1730-1760), was more suited to the teaching of poetry and rhetoric, to which chair he was shunted after one brief year.

Sensing the dearth of adequately trained native personnel, the government invited two Germans to the university, thus initiating a practice that would continue well into the next century. The story of the first ethnic Russian to hold the professorship in philosophy for any significant length of time is itself indicative of the precarious existence of philosophy in Russia for much of its history. Having already obtained a magister’s degree in 1760 with a thesis entitled “Rassuzhdenie o bessmertii dushi chelovechoj” (“A Treatise on the Immortality of the Human Soul”), Dmitry Anichkov (1733-1788) submitted in 1769 a dissertation on natural religion. Anichkov’s dissertation was found to contain atheistic opinions and was subjected to a lengthy 18-year investigation. Legend has it that the dissertation was publicly burned, although there is no firm evidence for this. As was common at the time, Anichkov used Wolffian philosophy manuals and during his first years taught in Latin.

Another notable figure at this time was S. Desnitsky (~1740-1789), who taught jurisprudence at Moscow University. Desnitsky attended university in Glasgow, where he studied under Adam Smith (1723-1790) and became familiar with the works of David Hume (1711-1776). The influence of Smith and British thought in general is evident in memoranda from February 1768 that Desnitsky wrote on government and public finance. Some of these ideas, in turn, appeared virtually verbatim in a portion of Catherine the Great’s famous Nakaz, or Instruction, published in April of that year.

Also in 1768 appeared Ya. Kozelsky’s Filosoficheskie predlozhenija (Philosophical Propositions), an unoriginal but noteworthy collection of numbered statements on a host of topics, not all of which were philosophical in a technical, narrow sense. By his own admission, the material dealing with “theoretical philosophy” was drawn from the Wolffians, primarily Baumeister, and that dealing with “moral philosophy” from the French Enlightenment thinkers, primarily Rousseau, Montesquieu, and Helvetius. The most interesting feature of the treatise is its acceptance of a social contract, of an eight-hour workday, the explicit rejection of great disparities of wealth and its silence on religion as a source of morality. Nevertheless, in his “theoretical philosophy,” Kozelsky (1728-1795) rejected atomism and the Newtonian conception of the possibility of empty space.

During Catherine’s reign, plans were made to establish several universities in addition to that in Moscow. Of course, nothing came of these. Moscow University itself had a difficult time attracting a sufficient number of students, most of whom came from poorer families. Undoubtedly, given the state of the Russian economy and society, the virtually ubiquitous attitude was that the study of philosophy was a sheer luxury with no utilitarian value. In terms of general education, the government evidently concluded that sending students abroad offered a better investment than spending large sums at home where the infrastructure needed much work and time to develop. Unfortunately, although there were some who returned to Russia and played a role in the intellectual life of the country, many more failed to complete their studies for a variety of reasons, including falling into debt. Progress, however, skipped a beat in 1796 when Catherine’s son and successor, Paul, ordered the recall of all Russian students studying abroad.

Despite its relatively small number of educational institutions, Russia felt a need to invite foreign scholars to help staff these establishments. One of the scholars, J. Schaden (1731-1797), ran a private boarding school in Moscow in addition to teaching philosophy at the university. The most notorious incident from these early years, however, involves the German Ludwig Mellman, who in the 1790s introduced Kant’s thought into Russia. Mellman’s advocacy found little sympathy even among his colleagues at Moscow University, and in a report to the Tsar the public prosecutor charged Mellman with “mental illness.” Not only was Mellman dismissed from his position, but he was forced to leave Russia as well.

Under the initiative of the new Tsar, Alexander I, two new universities were opened in 1804. With them, the need for adequately trained professors again arose. Once more the government turned to Germany, and, with the dislocations caused by the Napoleonic Wars, Russia stood in an excellent position to reap an intellectual harvest. Unfortunately, many of these invited scholars left little lasting impact on Russian thought. For example, one of the most outstanding, Johann Buhle (1763-1821), had already written a number of works on the history of philosophy before taking up residence in Moscow. Yet, once in Russia, his literary output plummeted, and his ignorance of the local language certainly did nothing to extend his influence.

Nonetheless, the sudden influx of German scholars, many of whom were intimately familiar with the latest philosophical developments, acted as an intellectual tonic on others. The arrival of the Swiss physicist Franz Bronner (1758-1850) at the new University of Kazan may have introduced Kant’s epistemology to the young future mathematician Lobachevsky. The Serb physicist, A. Stoikovich (1773-1832), who taught at Kharkov University, prepared a text for class use in which the content was arranged in conformity with Kant’s categories. One of the earliest Russian treatments of a philosophical topic, however, was A. Lubkin’s two “Pis’ma o kriticheskoj filosofii” (“Letters on Critical Philosophy”) from 1805. Lubkin (1770/1-1815), who at the time taught at the Petersburg Military Academy, criticized Kant’s theory of space and time for its agnostic implications saying that we obtain our concepts of space and time from experience. Likewise, in 1807 a professor of mathematics at Kharkov University, T. Osipovsky (1765-1832), delivered a subsequently published speech “O prostranstve i vremeni” (“On Space and Time”), in which he questioned whether, given the various considerations, Kant’s position was the only logical conclusion possible. Assuming the Leibnizian notion of a preestablished harmony, we can uphold all of Kant’s specific observations concerning space and time without concluding that they exist solely within our cognitive faculty. Osipovsky went on to make a number of other perceptive criticisms of Kant’s position, though Kant’s German critics already voiced many of these during his lifetime.

In the realm of social and political philosophy, as understood today, the most interesting and arguably the most sophisticated document from the period of the Russian Enlightenment is A. Kunitsyn’s Pravo estestvennoe (Natural Law). In his summary text consisting of 590 sections, Kunitsyn (1783-1840) clearly demonstrated the influence of Kant and Rousseau, holding that rational dictates concerning human conduct form moral imperatives, which we feel as obligations. Since each of us possesses reason, we must always be treated morally as ends, never as means toward an end. In subsequent paragraphs, Kunitsyn elaborated his conception of natural rights, including his belief that among these rights is freedom of thought and expression. His outspoken condemnation of serfdom, however, is not one that the Russian authorities could either have missed or passed over. Shortly after the text reached their attention, all attainable copies were confiscated, and Kunitsyn himself was dismissed from his teaching duties at St. Petersburg University in March 1821.

Another scholar associated with St. Petersburg University was Aleksandr I. Galich (1783-1848). Sent to Germany for further education, he there became acquainted with the work of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (1775-1854). With his return to Russia in 1813, he was appointed adjunct professor of philosophy at the Pedagogical Institute in St. Petersburg; and in 1819, when the institute was transformed into a university, Galich was named to the chair of philosophy. His teaching career, however, was short-lived, for in 1821 Galich was charged with atheism and revolutionary sympathies. Although stripped of teaching duties, he continued to draw a full salary until 1837. Galich’s importance lays not so much in his own quasi-Schellingian views as his pioneering treatments of the history of philosophy, aesthetics and philosophical anthropology. His two-volume Istorija filosofskikh sistem (History of Philosophical Systems) from 1818-19 concluded with an exposition of Schelling’s position and contained quite probably the first discussion in Russian of G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) and, in particular, of his Science of Logic. Galich’s Opyt nauki izjashchnogo (An Attempt at a Science of the Beautiful) from 1825 is certainly among the first Russian treatises in aesthetics. For Galich, the beautiful is the sensuous manifestation of truth and as such is a sub-discipline within philosophy. His 1834 work, Kartina cheloveka (A Picture of Man), marked the first Russian foray into philosophical anthropology. For Galich all “scientific” disciplines, including theology, are in need of an anthropological foundation; and, moreover, such a foundation must recognize the unity of the human aspects and functions, be they corporeal or spiritual.

The increasing religious and political conservativism that marked Tsar Alexander’s later years imposed onerous restrictions on the dissemination of philosophy, both in the classroom and in print. By the time of the Tsar’s death in 1825, most reputable professors of philosophy had already been administratively silenced or cowed into compliance. At the end of that year, the aborted coup known as the “Decembrist Uprising”—many of whose leaders had been exposed to the infection of Western European thought—only hardened the basically anti-intellectual attitude of the new Tsar Nicholas. Shortly after I. Davydov (1792/4-1863), hardly either an original or a gifted thinker, had given his introductory lecture “O vozmozhnosti filosofii kak nauki” (“On the Possibility of Philosophy as Science”) in May 1826 as professor of philosophy at Moscow University, the chair was temporarily abolished and Davydov shifted to teaching mathematics.

b. The Philosophical Dark Age (c. 1825-1860)

The reign of Nicholas I (1825-1855) was marked by intellectual obscurantism and an enforced philosophical silence, unusual even by Russian standards. The Minister of Public Education, A. Shishkov, blamed the Decembrist Uprising explicitly on the contagion of foreign ideas. To prevent their spread, he and Nicholas’s other advisors restricted the access of non-noble youths to higher education and had the tsar enact a comprehensive censorship law that held publishers legally responsible even after the official censor’s approval of a manuscript. Yet the scope of this new “cast-iron statute” was conceived so broadly that even at the time it was remarked that the Lord’s Prayer could be interpreted as revolutionary speech. While prevented an outlet in a dedicated professional manner at the universities, philosophy found energetic, though amateurish, expression first in the faculties of medicine and physics and then later in fashionable salons and social gatherings—where discipline, rigor and precision were held of little value. During these years, those empowered to teach philosophy at the universities struggled with the task of justifying the very existence of their discipline, not in terms of a search for truth, but as having some social utility. Given the prevailing climate of opinion, this proved to be a hard sell. The news of revolutions in Western Europe in 1848 was the last straw. All talk of reform and social change was simply ruled impermissible, and travel beyond the Empire’s borders was forbidden. Finally, in 1850, the minister of education took the step that was thought too extreme in the 1820s: in order to protect Russia from the latest philosophical systems, and therefore intellectual infection, the teaching of philosophy in public universities was simply to be eliminated. Logic and psychology were permitted, but only in the safe hands of theology professors. This situation persisted until 1863, when, in the aftermath of the humiliating Crimean War, philosophy reentered the public academic arena. Even then, however, severe restrictions on its teaching persisted until 1889!

Nevertheless, despite the oppressive atmosphere, some independent philosophizing emerged during the Nicholas years. At first, Schelling’s influence dominated abstract discussions, particularly those concerning the natural sciences and their place with regard to the other academic disciplines. However, the two chief Schellingians of the era—D. Vellansky (1774-1847) and M. Pavlov (1793-1840)—both valued German Romanticism, more for its sweeping conclusions than for either its arguments or its being the logical outcome of a philosophical development that had begun with Kant. Though both Vellansky and Pavlov penned a considerable number of works, none of them would find a place within today’s philosophy curriculum. Slightly later, in the 1830s and ’40s, the discussion turned to Hegel’s system, again with great enthusiasm but with little understanding either with what Hegel actually meant or with the philosophical backdrop of his writings. Not surprisingly, Hegel’s own self-described “voyage of discovery,” the Phenomenology of Spirit, remained an unknown text. Suffice it to say that, but for the dearth of original competent investigations at this time, the mere mention of the Stankevich and the Petrashevsky circles, the Slavophiles and the Westernizers, etc. in a history of philosophy text would be regarded a travesty.

Nevertheless, amid the darkness of official obscurantism, there were a few brief glimmers of light. In his 1833 Vvedenie v nauku filosofii (Introduction to the Science of Philosophy), F. Sidonsky (1805-1873) treated philosophy as a rational discipline independent of theology. Although conterminous with theology, Sidonsky regarded philosophy as both a necessary and a natural searching of the human mind for answers that faith alone cannot adequately supply. By no means did he take this to mean that faith and reason conflict. Revelation provides the same truths, but the path taken, though dogmatic and therefore rationally unsatisfying, is considerably shorter. Much more could be said about Sidonsky’s introductory text, but both it and its author were quickly consigned to the margins of history. Notwithstanding his book’s desired recognition in some secular circles, Sidonsky soon after its publication was shifted first from philosophy to the teaching of French and then simply dismissed from the St. Petersburg Ecclesiastic Academy in 1835. This time it was the clerical authorities who found his book, it was said, insufficiently rigorous from the official religious standpoint. Sidonsky spent the next 30 years (until the re-introduction of philosophy in the universities) as a parish priest in the Russian capital.

Among those who most resolutely defended the autonomy of philosophy during this “Dark Age” were O. Novitsky (1806-1884) and I. Mikhnevich (1809-1885), both of whom taught for a period at the Kiev Ecclesiastic Academy. Although neither was a particularly outstanding thinker and left no enduring works on the perennial philosophical problems, both stand out for refusing simply to subsume philosophy to religion or politics. Novitsky in 1834 accepted the professorship in philosophy at the new Kiev University, where he taught until the government’s abolition of philosophy, after which he worked as a censor. Mikhnevich, on the other hand, became an administrator.

One of the most interesting pieces of philosophical analysis from this time came from another Kiev scholar, S. Gogotsky (1813-1889). In his undergraduate thesis “Kriticheskij vzgljad na filosofiju Kanta” (“A Critical Look at Kant’s Philosophy”) from 1847, Gogotsky approached his topic from a moderate and informed Hegelianism, unlike that of his more vocal but dilettantish contemporaries. For Gogotsky, Kant’s thought represented a distinct improvement over the positions of empiricism and rationalism. However, he demonstrated his own extremism through his advocacy of such ideas as that of the uncognizability of things in themselves, the rejection of the real existence of things in space and time, the sharp dichotomy between moral duty and happiness, and so on. During this “Dark Age,” Gogotsky continued at Kiev University but taught pedagogy and remained silent on philosophical issues.

From our standpoint today, one of the most important characteristics of the philosophizing of the early “Kiev School” is the stress placed on the history of Western philosophy and particularly on epistemology. Mikhnevich, for example, wrote, “philosophy is the Science of consciousness… of the subject and the nature of our consciousness.” Based on statements such as this, some (A.Vvedensky, A. Nikolsky) have seen the influence of Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814).

The teaching of philosophy at this time was not eliminated from the ecclesiastic academies; the separate institutions of higher education were parallel to the secular universities for those from a clerical background. Largely with good reason, the government felt secure about their political and intellectual passivity. Among the most noteworthy of the professors at an ecclesiastic academy during the Nicholaevan years was F. Golubinsky (1798-1854), who taught in Moscow. Generally recognized as the founder of the “Moscow School of Theistic Philosophy,” his historical importance lies solely in his unabashed subordination of philosophy to theology and epistemology to ontology. For Golubinsky, humans seek knowledge in an attempt to recover an original diremption, a lost intimacy with the Infinite! Nevertheless, the idea of God is felt immediately within us. Owing to this immediacy, there is no need for and cannot be a proof of God’s existence. Such was the tenor of “philosophical” thought in the religious institutions of the time.

At the very end of the “Dark Age” one figure—the Owl of Minerva (or was it a phoenix?)—emerged who combined the scholarly erudition of his Kiev predecessors with the dominating “ontologism” of the theistic apologists, such as Golubinsky. P. Jurkevich (1826-1874) stood with one foot in the Russian philosophical past and one in the future. Serving as the bridge between the eras, he largely defined the contours along which philosophical discussions would be shaped for the next two generations.

c. The Emergence of Professional Philosophy (c. 1860-1917)

While a professor of philosophy at the Kiev Ecclesiastic Academy, Jurkevich in 1861 caught the attention of a well-connected publisher with a long essay in the obscure house organ of the Academy attacking Chernyshevsky’s materialism and anthropologism, which at the time were all the rage among Russia’s youth. Having decided to re-introduce philosophy to the universities, the government, nevertheless, worried, lest a limited and controlled measure of independent thought get out of hand. The decision to appoint Jurkevich to the professorship at Moscow University, it was hoped, would serve the government’s ends while yet combating fashionable radical trends.

In a spate of articles from his last three years in Kiev, Jurkevich forcefully argued in support of a number of seemingly disconnected theses but all of which demonstrated his own deep commitment to a Platonic idealism. His most familiar stance, his rejection of the popular materialism of the day, was directed not actually at metaphysical materialism but at a physicalist reductionism. Among the points Jurkevich made was that no physiological description could do justice to the revelations offered by introspective psychology and that the transformation of quantity into quality occurred not in the subject, as the materialists held, but in the interaction between the object and the subject. Jurkevich did not rule out the possibility that necessary forms conditioned this interaction, but, in keeping with the logic of this notion, he ruled out an uncognizable “thing in itself” conceived as an object without any possible subject.

Although Jurkevich already presented the scheme of his overall philosophical approach in his first article “Ideja” (“The Idea”) from 1859, his last, “Razum po ucheniju Platona i opyt po ucheniju Kanta” (“Plato’s Theory of Reason and Kant’s Theory of Experience”), written in Moscow, is today his most readable work. In it, he concluded (as did Spinoza and Hegel before him) that epistemology cannot serve as first philosophy—that is, that a body of knowledge need not and, indeed, cannot begin by asking for the conditions of its own possibility; in Jurkevich’s best-known expression: “In order to know it is unnecessary to have knowledge of knowledge itself.” Kant, he held, conceived knowledge not in the traditional, Platonic sense, as knowledge of what truly is, but in a radically different sense as knowledge of the universally valid. Hence, for Kant, the goal of science was to secure useful information, whereas for Plato science secured truth.

Unfortunately, Jurkevich’s style prevented a greater dissemination of his views. In his own day, his unfashionable views, cloaked as they were in scholastic language with frequent allusions to scripture, hardly endeared him to a young, secular audience. Jurkevich remained largely a figure of derision at the university. Today, it is these same qualities, together with his failure to elucidate his argument in distinctly rational terms, that make studying his writings both laborious and unsatisfying. In terms of immediate impact, he had only one student—V.Solovyov (see below). Yet, notwithstanding his meager direct impact, Jurkevic’s Christian Platonism proved deeply influential until at least the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

Unlike Jurkevich, P. Lavrov (1823-1900), a teacher of mathematics at the Petersburg Military Academy, actively aspired to a university chair in philosophy (namely, the one in the capital when the position was restored in the early 1860s). However, the government apparently already suspected Lavrov of questionable allegiance and, despite a recommendation from a widely respected scholar (K. Kavelin), awarded the position instead to Sidonsky.

In a series of lengthy essays written when he had university aspirations, Lavrov developed a position, which he termed “anthropologism,” that opposed metaphysical speculation, including the then-fashionable materialism of left-wing radicalism. Instead, he defended a simple epistemological phenomenalism that at many points bore a certain similarity to Kant’s position, though without the latter’s intricacies, nuances, and rigor. Essentially, Lavrov maintained that all claims regarding objects are translatable into statements about appearances or an aggregate of them. Additionally, he held that we have a collection of convictions concerning the external world, convictions whose basis lies in repeated experiential encounters with similar appearances. The indubitability of consciousness and our irresistible conviction in the reality of the external world are fundamental and irreducible. The error of both materialism and idealism, fundamentally, is the mistaken attempt to collapse one into the other. Since both are fundamental, the attempt to prove either is ill-conceived from the outset. Consistent with this skepticism, Lavrov argued that the study of “phenomena of consciousness,” a “phenomenology of spirit,” could be raised to a science only through introspection, a method he called “subjective.” Likewise, the natural sciences, built on our firm belief in the external world, need little support from philosophy. To question the law of causality, for example, is, in effect, to undermine the scientific standpoint.

Parallel to the two principles of theoretical philosophy, Lavrov spoke of two principles underlying practical philosophy. The first is that the individual is consciously free in his worldly activity. Unlike for Kant, however, this principle is not a postulate but a phenomenal fact; it carries no theoretical implications. For Lavrov, the moral sphere is quite autonomous from the theoretical. The second principle is that of “ideal creation.” Just as in the theoretical sphere we set ourselves against a real world, so in the practical sphere we set ourselves against ideals. Just as the real world is the source of knowledge, the world of our ideals serves as the motivation for action. In turning our own image of ourselves into an ideal, we create an ideal of personal dignity. Initially, the human individual conceives dignity along egoistic lines. In time, however, the individual’s interaction, including competition, with others gives rise to his conception of them as having equal claims to dignity and to rights. In linking rights to human dignity, Lavrov thereby denied that animals have rights.

Of a similar intellectual bent, N. Mikhailovsky (1842-1904) was even more of a popular writer than Lavrov. Nevertheless, Mikhailovsky’s importance in the history of Russian philosophy lies in his defense of the role of subjectivity in human studies. Unlike the natural sciences, the aim of which is the discovery of objective laws, the human sciences, according to Mikhailovsky, must take into account the epistemologically irreducible fact of conscious, goal-oriented activity. While not disclaiming the importance of objective laws, both Lavrov and Mikhailovsky held that social scientists must introduce a subjective, moral evaluation into their analyses. Unlike natural scientists, social scientists recognize the malleability of the laws under their investigation.

Comtean positivism, which for quite some years enjoyed considerable attention in 19th century Russia, found its most resolute and philosophically notable defender in V. Lesevich (1837-1905). Finding that it lacked a scientific grounding, Lesevich believed that positivism needed an inquiry into the principles that guide the attainment of knowledge. Such an inquiry must take for granted some body of knowledge without simply identifying itself with it. To the now-classic Hegelian charge that such a procedure amounted to not venturing into the water before learning how to swim, Lesevich replied that what was sought was not, so to speak, how to swim but, rather, the conditions that make swimming possible. In this vein, he consciously turned to the Kantian model while remaining highly critical of any talk of the a priori. In the end, Lesevich drew heavily upon psychology and empiricism for establishing the conditions of knowledge, thus leaving himself open to the charge of psychologism and relativism.

As the years passed, Lesevich moved from his early “critical realism,” which abhorred metaphysical speculation, to an appreciation for the positivism of Richard Avenarius and Ernst Mach. However, this very abhorrence, which was decidedly unfashionable, as well as his political involvement somewhat limited his influence.

Undoubtedly, of the philosophical figures to emerge in the 1870s, indeed arguably in any decade, the greatest was Vladimir Solovyov (1853-1900). In fact, if we view philosophy not as an abstract, independent inquiry but as a more or less sustained intellectual conversation, then we can precisely date the start of Russian secular philosophy: 24 November 1874, the day of Solovyov’s defense of his magister’s dissertation, Krizis zapadnoj filosofii (The Crisis of Western Philosophy). For only from that day forward do we find a sustained discussion within Russia of philosophical issues considered on their own terms, that is, without overt appeal to their extra-philosophical ramifications, such as their religious or political implications.

After completion and defense of his magister’s dissertation, Solovyov penned a highly metaphysical treatise entitled “Filosofskie nachala tsel’nogo znanija” (“Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge”), which he never completed. However, at approximately the same time, he also worked on what became his doctoral dissertation, Kritika otvlechennykh nachal (Critique of Abstract Principles)—the very title suggesting a Kantian influence. Although originally intended to consist of three parts, one each covering ethics, epistemology, and aesthetics, the completed work omitted the latter. For more than a decade, Solovyov remained silent on philosophical questions, preferring instead to concentrate on topical issues. When his interest was rekindled in the 1890s in preparing a second edition of his Kritika, a recognition of a fundamental shift in his views led him to recast their systemization in the form of an entirely new work, Opravdanie dobra (The Justification of the Good). Presumably, he intended to follow up his ethical investigations with respective treatises on epistemology and aesthetics. Unfortunately, Solovyov died having completed only three brief chapters of the “Theoretical Philosophy.”

Solovyov’s most relentless philosophical critic was B. Chicherin (1828-1904), certainly one of the most remarkable and versatile figures in Russian intellectual history. Despite his sharp differences with Solovyov, Chicherin himself accepted a modified Hegelian standpoint in metaphysics. Although viewing all of existence as rational, the rational process embodied in existence unfolds “dialectically.” Chicherin, however, parted with the traditional triadic schematization of the Hegelian dialectic, arguing that the first moment consists of an initial unity of the one and the many. The second and third moments, paths, or steps are antithetical and take various forms in different spheres, such as matter and reason or universal and particular. The final moment is a fusion of the two into a higher unity.

In the social and ethical realm, Chicherin placed great emphasis on individual human freedom. Social and political laws should strive for moral neutrality, permitting the flowering of individual self-determination. In this way, he remained a staunch advocate of economic liberalism, seeing essentially no role for government intervention. The government itself had no right to use its powers either to aim at a moral ideal or to force its citizens to seek an ideal. On the other hand, the government should not use its powers to prevent the citizenry from the exercise of private morality. Despite receiving less treatment than the negative conception of freedom, Chicherin nevertheless upheld the idealist conception of positive freedom as the striving for moral perfection and, in this way, reaching the Absolute.

Another figure to emerge in the late 1870s and 1880s was the neo-Leibnizian A. Kozlov (1831- 1901), who taught at Kiev University and who called his highly developed metaphysical stance “panpsychism.” As part of this stance, he, in contrast to Hume, argued for the substantial unity of the Self or I, which makes experience possible. This unity he held to be an obvious fact. Additionally, rejecting the independent existence of space and time, Kozlov held that they possessed being only in relation to thinking and sensing creatures. Like Augustine, however, Kozlov believed that God viewed time as a whole without our divisions into past, present, and future. To substantiate space and time, to attribute an objective existence to either, demands an answer to where and when to place them. Indeed, the very formulation of the problem presupposes a relation between a substantiated space or time and ourselves. Lastly, unlike Kant, Kozlov thought all judgments are analytic.

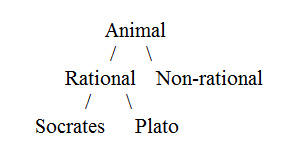

An unfortunately largely neglected figure to emerge in this period was M. Karinsky (1840- 1917), who taught philosophy at the St. Petersburg Ecclesiastic Academy. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Karinsky devoted much of his attention to logic and an analysis of arguments in Western philosophy, rather than metaphysical speculation. Unlike his contemporaries, Karinsky came to philosophy with an analytical bent rather than with a literary flair—a fact that made his writing style often decidedly torturous. True to those schooled in the Aristotleian tradition, Karinsky, like Brentano (to whom he has been compared) held that German Idealism was essentially irrationalist. Arguing against Kant, Karinsky believed that our inner states are not merely phenomenal, that the reflective self is not an appearance. Inner experience, unlike outer, yields no distinction between reality and appearance. In his general epistemology, Karinsky argued that knowledge was built on judgments, which were legitimate conclusions from premises. Knowledge, however, could be traced back to a set of ultimate unprovable, yet reliable, truths, which he called “self-evident.” Karinsky argued for a pragmatic interpretation of realism, saying that something exists in another room unperceived by me means I would perceive it if I were to go into that room. Additionally, he accepted an analogical argument for the existence of other minds similar to that of John Stuart Mill and Bertrand Russell.

In his two-volume magnum opus Polozhitel’nye zadachi filosofii (The Positive Tasks of Philosophy), L. Lopatin (1855-1920), who taught at Moscow University, defended the possibility of metaphysical knowledge. He claimed that empirical knowledge is limited to appearances, whereas metaphysics yields knowledge of the true nature of things. Although Lopatin saw Hegel and Spinoza as the definitive expositors of rationalistic idealism, he rejected both for their very transformation of concrete relations into rational or logical ones. Nevertheless, Lopatin affirmed the role of reason particularly in philosophy in conscious opposition to, as he saw it, Solovyov’s ultimate surrender to religion. In the first volume, he attacked materialism as itself a metaphysical doctrine that elevates matter to the status of an absolute that cannot explain the particular properties of individual things or the relation between things and consciousness. In his second volume, Lopatin distinguishes mechanical causality from “creative causality,” according to which one phenomenon follows another, though with something new added to it. Despite his wealth of metaphysical speculation, quite foreign to most contemporary readers, Lopatin’s observations on the self or ego derived from speculation that is not without some interest. Denying that the self has a purely empirical nature, Lopatin emphasized that the undeniable reality of time demonstrated the non-temporality of the self, for temporality could only be understood by that which is outside time. Since the self is extra-temporal, it cannot be destroyed, for that is an event in time. Likewise, in opposition to Solovyov, Lopatin held that the substantiality of the self is immediately evident in consciousness.

In the waning years of the 19th century, neo-Kantianism came to dominate German philosophy. Because of the increasing tendency to send young Russian graduate students to Germany for additional training, it should come as no surprise that that movement gained a foothold in Russia too. In one of the very few Russian works devoted to philosophy of science A. Vvedensky (1856-1925) presented, in his lengthy dissertation, a highly idealistic Kantian interpretation of the concept of matter as understood in the physics of his day. He tried therein to defend and update Kant’s own work as exemplified in the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. Vvedensky’s book, however, attracted little attention and exerted even less influence. Much more widely recognized were his own attempts in subsequent years, while teaching at St. Petersburg University, to recast Kant’s transcendental idealism in, what he called, “logicism.” Without drawing any conclusions based upon the nature of space and time, Vvedensky believed it possible to prove the impossibility of metaphysical knowledge and, as a corollary so to speak, that everything we know, including our own self, is merely an appearance, not a thing in itself. Vvedensky was also willing to cede that the time and the space in which we experience everything in the world are also phenomenal. Although metaphysical knowledge is impossible, metaphysical hypotheses, being likewise irrefutable, can be brought into a world-view based on faith. Particularly useful are those demanded by our moral tenets such as the existence of other minds.

The next two decades saw a blossoming of academic philosophy on a scale hardly imaginable just a short time earlier. Most fashionable Western philosophies of the time found adherents within the increasingly professional Russian scene. Even Friedrich Nietzsche’s thought began to make inroads, particularly among certain segments of the artistic community and among the growing number of political radicals. Nonetheless, few, particularly during these formative years, adopted any Western system without significant qualifications. Even those who were most receptive to foreign ideas adapted them in line with traditional Russian concerns, interests, and attitudes. One of these traditional concerns was with Platonism in general. Some of Plato’s dialogues appeared in a Masonic journal as early as 1777, and we can easily discern an interest in Plato’s ideas as far back as the medieval period. Possibly the Catholic assimilation of Aristotelianism had something to do with the Russian Orthodox Church’s emphasis on Plato. And again possibly this interest in Plato had something to do with the metaphysical and idealistic character of much classic Russian thought as against the decidedly more empirical character of many Western philosophies. We have already noted the Christian Platonism of Jurkevich, and his student Solovyov, who with his central concept of “vseedinstvo” (“total-unity”) can, in turn, also be seen as a modern neo-Platonist.

In the immediate decades preceding the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, a veritable legion of philosophers worked in Solovyov’s wide shadow. Among the most prominent of these was S. Trubetskoi (1862-1905). The Platonic strain of his thought is evident in the very topics Trubetskoi chose for his magister’s and doctoral theses: Metaphysics in Ancient Greece, 1890 and The History of the Doctrine of Logos, 1900, respectively. It is, however, in his programmatic essays “O prirode chelovecheskovo soznanija” (“The Nature of Human Consciousness”), 1889-1891 and “Osnovanija idealizma” (“The Foundations of Idealism”), 1896 that Trubetskoi elaborated his position with regard to modern philosophy. Holding that the basic problem of contemporary philosophy is whether human knowledge is of a personal nature, Trubetskoi maintained that modern Western philosophers relate personal knowledge to a personal consciousness. Herein lies their error. Human consciousness is not an individual consciousness, but, rather, an on-going universal process. Likewise, this process is a manifestation not of a personal mind but of a cosmic one. Personal consciousness, as he puts it, presupposes a collective consciousness, and the latter presupposes an absolute consciousness. Kant’s great error was in conceiving the transcendental consciousness as subjective. In the second of the essays mentioned above, Trubetskoi claims that there are three means of knowing reality: empirically through the senses, rationally through thought, and directly through faith. For him, faith is what convinces us that there is an external world, a world independent of my subjective consciousness. It is faith that underlies our accepting the information provided by our sense organs as reliable. Moreover, it is faith that leads me to think there are in the world other beings with a mental organization and capacity similar to mine. However, Trubetskoi rejects equating his notion of faith with the passive “intellectual intuition” of Schelling and Solovyov. For Trubetskoi, faith is intimately connected with the will, which is the basis of my individuality. My discovery of the other is grounded in my desire to reach out beyond myself, that is, to love.

Although generally characterized as a neo-Leibnizian, N. Lossky (1870-1965) was also greatly influenced by a host of Russian thinkers including Solovyov and Kozlov. In addition to his own views, Lossky, having studied at Bern and Goettingen among other places, is remembered for his pioneering studies of contemporary German philosophy. He referred to Edmund Husserl‘s Logical Investigations already as early as 1906, and in 1911 he gave a course on Husserl’s “intentionalism.” Despite this early interest in strict epistemological problems, Lossky in general drew ever closer to the ontological concerns and positions of Russian Orthodoxy. He termed his epistemological views “intuitivism,” believing that the cognitive subject apprehends the external world as it is in itself directly. Nevertheless, the object of cognition remains ontologically transcendent, while epistemologically immanent. This direct penetration into reality is possible, Lossky tells us, because all worldly entities are interconnected into an “organic whole.” Additionally, all sensory properties of an object (for example, its color, texture, temperature, and so on) are actual properties of the object, our sense stimulation serving merely to direct our mental attention to those properties. That different people see one object in different ways is explained as a result of different ways individuals have of getting their attention directly towards one of the object’s numerous properties. All entities, events, and relations that lack a temporal and spatial character possess “ideal being” and are the objects of “intellectual intuition.” Yet, there is another, a third, realm of being that transcends the laws of logic (here we see the influence of Lossky’s teacher, Vvedensky), which he calls “metalogical being” and is the object of mystical intuition.

Another kindred spirit was S. Frank (1877-1950), who in his early adult years was involved with Marxism and political activities. His magister’s thesis Predmet znanija (The Object of Knowledge), 1915, is notable as much for its masterful handling of current Western philosophy as for its overall metaphysical position. Demonstrating a grasp not only of German neo-Kantianism, Frank drew freely from, among many others, Husserl, Henri-Louis Bergson, and Max Scheler; he may even have been the first in Russian to refer to Gottlob Frege, whose Foundations of Arithmetic Frank calls “one of the rare genuinely philosophical works by a mathematician.” Frank contends that all logically determined objects are possible thanks to a metalogical unity, which is itself not subject to the laws of logic. Likewise, all logical knowledge is possible thanks solely to an “intuition,” an “integral intuition,” of this unity. Such intuition is possible because all of us are part of this unity or Absolute. In a subsequent book Nepostizhimoe (The Unknowable), 1939, Frank further elaborated his view stating that mystical experience reveals the supra-logical sphere in which we are immersed but which cannot be conceptually described. Although there is a great deal more to Frank’s thought, we see that we are quickly leaving behind the secular, philosophical sphere for the religious, if not mystical.

No survey, however brief, of Russian thinkers under Solovyov’s influence would be satisfactory without mention of the best known of these in the West, namely N. Berdjaev (1874-1948). Widely hailed as a Christian existentialist, he began his intellectual journey as a Marxist. However, by the time of his first publications he was attempting to unite a revolutionary political outlook with transcendental idealism, particularly a Kantian ethic. Within the next few years, Berdjaev’s thought evolved quickly and decisively away from Marxism and away from critical idealism to an outright Orthodox Christian idealism. On the issue of free will versus determinism, Berdjaev moved from an initial acceptance of soft determinism to a resolute incompatibilist. Morality, he claimed, demanded his stand. Certainly, Berdjaev was among the first, if not the first, philosopher of his era to diminish the importance of epistemology in place of ontology. In time, however, he himself made clear that the pivot of his thought was not the concept of Being, as it would be for some others, and even less that of knowledge, but, rather, the concept of freedom. Acknowledging his debt to Kant, Berdjaev too saw science as providing knowledge of phenomenal reality but not of actuality, of things as they are in themselves. However applicable the categories of logic and physics may be to appearances, they are assuredly inapplicable to the noumenal world and, in particular, to God. In this way Berdjaev does not object to the neo-Kantianism of Vvedensky, for whom the objectification of the world is a result of functioning of the human cognitive apparatus, but only that it does not go far enough. There is another world or realm, namely one characterized by freedom.

Just as all of the above figures drew inspiration from Christian neo-Platonism, so too did they all feel the need to address the Kantian heritage. Lossky’s dissertation Obosnovanie intuitivizma (The Foundations of Intuitivism), for example, is an extended engagement with Kant’s epistemology, Lossky himself having prepared a Russian translation of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason comparable in style and adequacy to Norman Kemp Smith’s famous rendering into English. Trubetskoi called Kant the “Copernicus of modern philosophy,” who “discovered that there is an a priori precondition of all possible experience.” Nevertheless, among the philosophers of this era, not all saw transcendental idealism as a springboard to religious and mystical thought. A student of Vvedensky’s, I. Lapshin (1870-1952) in his dissertation, Zakony myshlenija i formy poznanija (The Laws of Thought and the Forms of Cognition), 1906, attempted to show that, contrary to Kant’s stand, space and time were categories of cognition and that all thought, even logical, relies on a categorical synthesis. Consequently, the laws of logic are themselves synthetic, not analytic, as Kant had thought and are applicable only within the bounds of possible experience.

G. Chelpanov (1863-1936), who taught at Moscow University, was another with a broadly conceived Kantian stripe. Remembered as much, if not more so, for his work in experimental psychology as in philosophy, Chelpanov, unlike many others, wished to retain the concept of the thing-in-itself, seeing it as that which ultimately “evokes” a particular representation of an object. Without it, contended Chelpanov, we are left (as in Kant) without an explanation of why we perceive this, and not that, particular object. In much the same manner, we must appeal to some transcendent space in order to account for why we see an object in this spot and not another. For these reasons, Chelpanov called his position “critical realism” as opposed to the more usual construal of Kantianism as “transcendental idealism.” In psychology, Chelpanov upheld the psychophysical parallelism of Wilhelm Wundt.

As the years of the First World War approached, a new generation of scholars came to the fore who returned to Russia from graduate work in Germany broadly sympathetic to one or even an amalgam of the schools of neo-Kantianism. Among these young scholars, the works of B. Kistjakovsky (1868-1920) and P. Novgorodtsev (1866-1924) stand out as arguably the most accessible today for their analytic approach to questions of social-science methodology.

During this period, Husserlian phenomenology was introduced into Russia from a number of sources, but its first and, in a sense, only major propagandist was G. Shpet (1879-1937), whom we have referred to earlier. In any case, besides his historical studies Shpet did pioneering work in hermeneutics as early as 1918. Additionally, in two memorable essays he respectively argued, along the lines of the early Husserl and the late Solovyov, against the Husserlian view of the transcendental ego and in the other traced the Husserlian notion of philosophy as a rigorous science back to Parmenides.

Regrettably, Shpet was permanently silenced during the Stalinist era, but A. Losev (1893-1988), whose early works fruitfully employed some early phenomenological techniques, survived and blossomed in its aftermath. Concentrating on ancient Greek thought, particularly aesthetics, his numerous publications have yet to be assimilated into world literature, although during later years his enormous contributions were recognized within his homeland and by others to whom they were linguistically accessible. It must be said, nonetheless, that Losev’s personal pronouncements hark back to a neo-Platonism completely at odds with the modern temperament.

d. The Soviet Era (1917-1991)

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 ushered in a political regime with a set ideology that countenanced no intellectual competition. During the first few years of its existence, Bolshevik attention was directed towards consolidating political power, and the selection of university personnel in many cases was left an internal matter. In 1922, however, most explicitly non-Marxist philosophers who had not already fled were banished from the country. Many of them found employment, at least for a time, in the major cities of Europe and continued their personal intellectual agendas. None of them, however, during their lifetimes significantly influenced philosophical developments either in their homeland or in the West, and few, with the notable exception of Berdyaev, received wide recognition.

During the first decade of Bolshevik rule, the consuming philosophical question concerned the role of Marxism with regard to traditional academic disciplines, particularly those that had either emerged since Karl Marx’s death or had seen recent breathtaking developments that had reshaped the field. The best known dispute occurred between the “mechanists” and the “dialecticians” or “Deborinists,” after its principal advocate A. Deborin (1881-1963). Since a number of individuals composed both groups and the issues in dispute evolved over time, no simple statement of the respective stances can do complete justice to either. Nevertheless, the mechanists essentially held that philosophy as a separate discipline had no reason for being within the Soviet state. All philosophical problems could and would be resolved by the natural sciences. The hallowed dialectical method of Marxism was, in fact, just the scientific method. The Deborinists, on the other hand, defended the existence of philosophy as a separate discipline. Indeed, they viewed the natural sciences as built on a set of philosophical principles. Unlike the mechanists, they saw nature as fundamentally dialectical, which could not be reduced to simpler mechanical terms. Even human history and society proceeded dialectically in taking leaps that resulted in qualitatively different states. The specifics of the controversy, which raged until 1929, are of marginal philosophical importance now, but to some degree the basic issue of the relation of philosophy to the sciences, of the role of the former with regard to the latter, endures to this day. Regrettably, politics played as much of a role in the course of the dispute as abstract reasoning, and the outcome was a simple matter of a political fiat with the Deborinists gaining a temporary victory. Subsequent events over the next two decades, such as the defeat of the Deborinists, have nothing to do with philosophy. What philosophy did continue to be pursued during these years within Russia was kept a personal secret, any disclosure of which was at the expense of one’s life. To a certain degree, the issue of the role of philosophy arose again in the 1950s when the philosophical implications of relativity theory became a disputed subject. Again, the issue arose of whether philosophy or science had priority. This time, however, with atomic weapons securely in hand there could be no doubt as to the ultimate victor with little need for political intervention.

Another controversy, though less vociferous, concerned psychological methodology and the very retention of such common terms as “consciousness,” “psyche,” and “attention.” The introspective method, as we saw advocated by many of the idealistic philosophers, was seen by the new ideologues as subjective and unscientific in that it manifestly referred to private phenomena. I. Pavlov (1849-1936), already a star of Russian science at the time of the Revolution, was quickly seen as utilizing a method that subjected psychic activity to the objective methods of the natural sciences. The issue became, however, whether the use of objective methods would eliminate the need to invoke such traditional terms as “consciousness.” The central figure here was V. Bekhterev (1857-1927), who believed that since all mental processes eventually manifested themselves in objectively observable behavior, subjective terminology was superfluous. Again, the discussion was silenced through political means once a victory was secured over the introspectionists. Bekhterev’s behaviorism was itself found to be dangerously leftist.

As noted above, during the 1930s and ’40s, independent philosophizing virtually ceased to exist, and what little was published is of no more than historical interest. Indicative of the condition of Russian thought at this time is the fact that when in 1946 the government decided to introduce logic into the curriculum of secondary schools the only suitable text available was a slim book by Chelpanov dating from before the Revolution. After Joseph Stalin’s death, a relative relaxation or “thaw” in the harsh intellectual climate was permitted, of course within the strict bounds of the official state ideology. In addition to the re-surfacing of the old issue of the role of Marxism with respect to the natural sciences, Russian scholars sought a return to the traditional texts in hopes of understanding the original inspiration of the official philosophy. Some, such as the young A. Zinoviev (1922-2006) sought an understanding of “dialectical logic” in terms of the operations, procedures and techniques employed in political economics. Others, for example, V. Tugarinov, drew heavily on Hegel’s example in attempting to delineate a system of fundamental categories.

After the formal recognition in the validity of formal logic, it received significant attention in the ensuing years by Zinoviev, D. Gorsky, and E. Voishvillo, among many others. Their works have deservedly received international attention and made no use of the official ideology. What sense, if any, to make of “dialectical logic” was another matter that could not remain politically neutral. Until the last days of the Soviet period, there was no consensus as to what it is or its relation to formal logic. One of the most resolute defenders of dialectical logic was E. Ilyenkov, who has received attention even in the West. In epistemology too, surface agreement, demonstrated through use of an official vocabulary obscured (but did not quite hide) differences of opinion concerning precisely how to construe the official stand. It certainly now appears that little of enduring worth in this field was published during the Soviet years. However, some philosophers who were active at that time produced works that only recently have been published. Perhaps the most striking example is M. Mamardashvili (1930-1990), who during his lifetime was noted for his deep interest in the history of philosophy and his anti-Hegelian stands.

Most work in ethics in the Soviet period took a crude apologetic form of service to the state. In essence, the good is that which promotes the stated goals of Soviet society. Against such a backdrop, Ja. Mil’ner-Irinin’s study Etika ili printsy istinnoj chelovechnosti (Ethics or The Principles of a True Humanity) is all the more remarkable. Although only an excerpt appeared in print in the 1960s, the book-length manuscript, which as a whole was rejected for publication, was circulated and discussed. The author presented a normative system that he held to be universally valid and timeless. Harking back to the early days of German Idealism, Mil’ner-Irinin urged being true to one’s conscience as a moral principle. However, he claimed he deduced his deontology from human social nature rather than from the idea of rationality (as in Kant).

After the accession of L. Brezhnev to the position of General Secretary and particularly after the events that curtailed the Prague Spring in 1968, all signs of independent philosophizing beat a speedy retreat. The government anxiously launched a campaign for ideological vigilance, which a German scholar, H. Dahm, termed an “ideological counter-reformation,” that persisted until the “perestroika” of the Gorbachev years.

e. The Post-Soviet Era (1991-)

Clearly, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the relegation of the Communist Party to the political opposition has also ushered in a new era in the history of Russian philosophy. What trends will emerge is still too early to tell. How Russian philosophers will eventually evaluate their own recent, as well as tsarist, past may turn to a large degree on the country’s political and economic fortunes. Not surprisingly, the 1990s saw, in particular, a “re-discovery” of the previously forbidden works of the religious philosophers active just prior to or at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution. Whether Russian philosophers will continue along these lines or approach a style resembling Western “analytical” trends remains an open question.

3. Concluding Remarks

In the above historical survey we have emphasized Russian epistemological over ontological and ethical concerns, hopefully without neglecting or disparaging them. Admittedly, doing so may reflect a certain “Western bias.” Nevertheless, such a survey, whatever its deficiencies, shows that questions regarding the possibility of knowledge have never been completely foreign to the Russian mind. This we can unequivocally state without dismissing Masaryk’s position, for indeed during the immediate decades preceding the 1917 Revolution epistemology was not accorded special attention, let alone priority. Certainly at the time when Masaryk formulated his position, Russian philosophy was relatively young. Nonetheless, were the non-critical features of Russian philosophy, which Masaryk so correctly observed, a reflection of the Russian mind as such or were they a reflection of the era observed? If one were to view 19th century German philosophy from the rise of Hegelianism to the emergence of neo-Kantianism, would one not see it as shortchanging epistemology? Could it not be that our error lay in focussing on a single period in Russian history, albeit the philosophically most fruitful one? In any case, the mere existence of divergent opinions during the Soviet era—however cautiously these had to be expressed—on recurring fundamental questions testifies to the tenacity of philosophy on the human mind.

Rather than ask for the general characteristics of Russian philosophy, should we not ask why philosophy arose so late in Russia compared to other nations? Was Vvedensky correct that the country lacked suitable educational institutions until relatively recently, or was he writing as a university professor who saw no viable alternative to make a living? Could it be that Shpet was right in thinking that no one found any utilitarian value in philosophy except in modest service to theology, or was he merely expressing his own fears for the future of philosophy in an overtly ideological state? Did Masaryk have grounds for linking the late emergence of philosophy in Russia to the perceived anti-intellectualism of Orthodox theology, or was he simply speaking as a Unitarian. Finally, intriguing as this question may be, are we not in searching for an answer guilty of what some would label the mistake of reductionism, that is, of trying to resolve a philosophical problem by appeal to non-philosophical means?

4. References and Further Reading

Secondary works in Western languages:

- Copleston, Frederick C. Philosophy in Russia, From Herzen to Lenin and Berdyaev, Notre Dame, 1986.

- Dahm, Helmut. Der gescheiterte Ausbruch: Entideologisierung und ideologische Gegenreformation in Osteuropa (1960-1980), Baden-Baden, 1982.

- DeGeorge, Richard T. Patterns of Soviet Thought, Ann Arbor, 1966.

- Goerdt, W. Russische Philosophie: Zugaenge und Durchblicke, Freiburg/Muenchen, 1984.

- Joravsky, David. Soviet Marxism and Natural Science 1917-1932, NY, 1960.

- Koyre, Alexandre. La philosophie et le probleme national en Russie au debut du XIXe siecle, Paris, 1929.

- Lossky, Nicholas O. History of Russian Philosophy, New York, 1972.

- Masaryk, Thomas Garrigue. The Spirit of Russia, trans. Eden & Cedar Paul, NY, 1955.

- Scanlan, James P. Marxism in the USSR, A Critical Survey of Current Soviet Thought, Ithaca, 1985

- Walicki, Andrzej. A History of Russian Thought from the Enlightenment to Marxism, Stanford, 1979.

- Zenkovsky, V. V. A History of Russian Philosophy, trans. George L. Kline, London, 1967.

Author Information

Thomas Nemeth

Email: t_nemeth@yahoo.com

U. S. A.

A prominent salonnière in seventeenth-century Paris, Madame de Sablé has long occupied the background of early modern French philosophy. She has survived in intellectual history as the patron of La Rochefoucauld, as the hostess of a theological salon, and as the correspondent of Blaise Pascal and Antoine Arnauld. These ancillary roles have obscured her original contributions to moral philosophy in her writings. In her maxims, Sablé develops a distinctive critique of moral virtue. She claims that virtue is a mask of vice; usually of pride, and that self-interest is the habitual motor behind altruistic actions. This critique of virtue is a social critique inasmuch as it unmasks the mechanism of self-aggrandizement under the cover of virtue in the court hierarchy of the period. With her characteristic moderation, Sablé insists that friendship constitutes an exception to the social charade of masked self-interest. In the intimacies of mutually sacrificial friendship, authentic virtue can flourish. Sablé’s dismissal of the claims of natural moral virtue, and her fideistic insistence that true moral order can only be grasped in the light of faith, reflect her adherence to Jansenism, the

A prominent salonnière in seventeenth-century Paris, Madame de Sablé has long occupied the background of early modern French philosophy. She has survived in intellectual history as the patron of La Rochefoucauld, as the hostess of a theological salon, and as the correspondent of Blaise Pascal and Antoine Arnauld. These ancillary roles have obscured her original contributions to moral philosophy in her writings. In her maxims, Sablé develops a distinctive critique of moral virtue. She claims that virtue is a mask of vice; usually of pride, and that self-interest is the habitual motor behind altruistic actions. This critique of virtue is a social critique inasmuch as it unmasks the mechanism of self-aggrandizement under the cover of virtue in the court hierarchy of the period. With her characteristic moderation, Sablé insists that friendship constitutes an exception to the social charade of masked self-interest. In the intimacies of mutually sacrificial friendship, authentic virtue can flourish. Sablé’s dismissal of the claims of natural moral virtue, and her fideistic insistence that true moral order can only be grasped in the light of faith, reflect her adherence to Jansenism, the

A notable Enlightenment polymath, Joseph Priestley published almost two hundred works on natural philosophy, theology, metaphysics, political philosophy, politics, education, history and linguistics. Remembered today primarily as a scientist who isolated oxygen, Priestley considered his calling to be that of a theologian, and he spent most of his life working as a minister and teacher. He combined his Unitarian theology with an associationist, materialist and determinist philosophy to create a coherent world-view that was the subject of bitter controversy.

A notable Enlightenment polymath, Joseph Priestley published almost two hundred works on natural philosophy, theology, metaphysics, political philosophy, politics, education, history and linguistics. Remembered today primarily as a scientist who isolated oxygen, Priestley considered his calling to be that of a theologian, and he spent most of his life working as a minister and teacher. He combined his Unitarian theology with an associationist, materialist and determinist philosophy to create a coherent world-view that was the subject of bitter controversy. A major poet during the reign of Louis XIV in France, Madame Deshoulières used her writings to defend philosophical

A major poet during the reign of Louis XIV in France, Madame Deshoulières used her writings to defend philosophical  Madame de la Sablière made distinctive contributions to moral and religious philosophy in 17th century France. Her

Madame de la Sablière made distinctive contributions to moral and religious philosophy in 17th century France. Her  C.S. Peirce was a scientist and philosopher best known as the earliest proponent of

C.S. Peirce was a scientist and philosopher best known as the earliest proponent of

Plotinus is considered to be the founder of

Plotinus is considered to be the founder of  The views of