Anselm of Canterbury (1033—1109)

Saint Anselm was one of the most important Christian thinkers of the eleventh century. He is most famous in philosophy for having discovered and articulated the so-called “ontological argument;” and in theology for his doctrine of the atonement. However, his work extends to many other important philosophical and theological matters, among which are: understanding the aspects and the unity of the divine nature; the extent of our possible knowledge and understanding of the divine nature; the complex nature of the will and its involvement in free choice; the interworkings of human willing and action and divine grace; the natures of truth and justice; the natures and origins of virtues and vices; the nature of evil as negation or privation; and the condition and implications of original sin.

Saint Anselm was one of the most important Christian thinkers of the eleventh century. He is most famous in philosophy for having discovered and articulated the so-called “ontological argument;” and in theology for his doctrine of the atonement. However, his work extends to many other important philosophical and theological matters, among which are: understanding the aspects and the unity of the divine nature; the extent of our possible knowledge and understanding of the divine nature; the complex nature of the will and its involvement in free choice; the interworkings of human willing and action and divine grace; the natures of truth and justice; the natures and origins of virtues and vices; the nature of evil as negation or privation; and the condition and implications of original sin.

In the course of his work and thought, unlike most of his contemporaries, Anselm deployed argumentation that was in most respects only indirectly dependent on Sacred Scripture, Christian doctrine, and tradition. Anselm also developed sophisticated analyses of the language used in discussion and investigation of philosophical and theological issues, highlighting the importance of focusing on the meaning of the terms used rather than allowing oneself to be misled by the verbal forms, and examining the adequacy of the language to the objects of investigation, particularly to the divine nature. In addition, in his work he both discussed and exemplified the resolution of apparent contradictions or paradoxes by making appropriate distinctions. For these reasons, one title traditionally accorded him is the Scholastic Doctor, since his approach to philosophical and theological matters both represents and contributed to early medieval Christian Scholasticism.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Influences

- Methodology: Faith and Reason

- The Proslogion

- Gaunilo’s Reply and Anselm’s Response

- The Monologion

- Cur Deus Homo

- De Grammatico

- The De Veritate

- The De Libertate Arbitrii

- The De Casu Diaboli

- The De Concordia

- The Fragments

- Other Writings

- References and Further Readings

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

1. Life

Anselm was born in 1033 in Aosta, a border town of the kingdom of Burgundy. In his adolescence, he decided that there was no better life than the monastic one. He sought to become a monk, but was refused by the abbot of the local monastery. Leaving his birthplace as a young man, he headed north across the Alps to France, eventually arriving at Bec in Normandy, where he studied under the eminent theologian and dialectician Lanfranc, whose involvement in disputes with Berengar spurred a revival in theological speculation and application of dialectic in theological argument. At the monastery of Bec, Anselm devoted himself to scholarship, and found an earlier childhood attraction to the monastic life reawakening. Unable to decide between becoming a monk at Bec or Cluny, becoming a hermit, or living off his inheritance and giving alms to the poor, he put the decision in the hands of Lanfranc and Maurilius, the Archbishop of Rouen, who decided Anselm should enter monastic life at Bec, which he did in 1060.

In 1063, after Lanfranc left Bec for Caen, Anselm was chosen to be prior. Among the various tasks Anselm took on as prior was that of instructing the monks, but he also had time left for carrying on rigorous spiritual exercises, which would play a great role in his philosophical and theological development. As his biographer, Eadmer, writes: “being continually given up to God and to spiritual exercises, he attained such a height of divine speculation that he was able by God’s help to see into and unravel many most obscure and previously insoluble questions…” (1962, p. 12). He became particularly well known, both in the monastic community and in the wider community, not only for the range and depth of his insight into human nature, the virtues and vices, and the practice of moral and religious life, but also for the intensity of his devotions and asceticism.

In 1070, Anselm began to write, particularly prayers and meditations, which he sent to monastic friends and to noblewomen for use in their own private devotions. He also engaged in a great deal of correspondence, leaving behind numerous letters. Eventually, his teaching and thinking culminated in a set of treatises and dialogues. In 1077, he produced the Monologion, and in 1078 the Proslogion. Eventually, Anselm was elected abbot of the monastery. At some time while still at Bec, Anselm wrote the De Veritate (On Truth), De Libertate Arbitrii (On Freedom of Choice), De Casu Diaboli (On the Fall of the Devil), and De Grammatico.

In 1092, Anselm traveled to England, where Lanfranc had previously been arch-bishop of Canterbury. The Episcopal seat had been kept vacant so King William Rufus could collect its income, and Anselm was proposed as the new bishop, a prospect neither the king nor Anselm desired. Eventually, the king fell ill, changed his mind in fear of his demise, and nominated Anselm to become bishop. Anselm attempted to argue his unfitness for the post, but eventually accepted. In addition to the typical cares of the office, his tenure as arch-bishop of Canterbury was marked by nearly uninterrupted conflict over numerous issues with King William Rufus, who attempted not only to appropriate church lands, offices, and incomes, but even to have Anselm deposed. Anselm had to go into exile and travel to Rome to plead the case of the English church to the Pope, who not only affirmed Anselm’s position, but refused Anselm’s own request to be relieved of his office. While archbishop in exile, however, Anselm did finish his Cur Deus Homo, also writing the treatises Epistolae de Incarnatione Verbi (On the Incarnation of the Word), De Conceptu Virginali et de Originali Peccato (On the Virgin Conception and on Original Sin), De Processione Spiritus Sancti (On the Proceeding of the Holy Spirit), and De Concordia Praescientia et Praedestinationis et Gratiae Dei cum Libero Arbitrio (On the Harmony of the Foreknowledge, the Predestination, and the Grace of God with Free Choice).

Upon returning to England after William Rufus’s death, conflict eventually ensued between the archbishop and the new king, Henry I, requiring Anselm once again to travel to Rome. When judgment was made by Pope Paschal II in Anselm’s favor, the king forbade him to return to England, but eventually reconciliation took place. Anselm died in 1109, leaving behind several pupils and friends of some importance, among them Eadmer, Anselm’s biographer, and the theologian Gilbert Crispin. He was declared a doctor of the Roman Catholic Church in 1720, and is considered a saint by the Roman Catholic Church and the churches in the Anglican Communion.

Today, Anselm is most well known for his Proslogion proof for the existence of God, but his thought was widely known in the Middle Ages, and still today in certain circles of scholarship, particularly among religious scholars, for considerably more than that single achievement. For fuller biographies of Anselm, see Eadmer’s Vita Sancti Anselmi/ The Life of St. Anselm: Archbishop of Canterbury, and Alexander’s Liber ex dictis beati Anselmi.

2. Influences

With the exception of St. Augustine, and to a lesser extent Boethius, it is difficult to definitively ascribe the influence of other thinkers to the development of St. Anselm’s thought. To be sure, Anselm studied under Lanfranc, but Lanfranc does not appear to have been a significant influence on the actual content or expression of Anselm’s thought, and he largely ignored Lanfranc’s misgivings about the method of theMonologion. Anselm cites Boethius, but does not draw upon him extensively. Other figures have been proposed as influences on Anselm, for instance John Scotus Eriugena and Pseudo-Dionysus, but any such proposals are set in the proper framework by these remarks from Koyré: “The influence of these two great thinkers is not at all lacking in verisimilitude a priori.” (Koyré 1923, 109). It is possible that either one of them, or other thinkers, influenced Anselm, but going beyond mere possibility given the texts we possess is controversial.

Discerning influences on Anselm’s work is for the most part conjectural, precisely because Anselm makes so few references to previous thinkers in his work. In the preface to the Monologion he writes: “Reexamining the work often myself, I have been able to find nothing that I have said in it, that would not agree [cohaereat] with the writings of the Catholic Fathers and especially with those of the blessed Augustine.” (S. v. 1, p.8)

[All citations of Anselm’s texts (except for the Fragments) are the author’s translations from S. Anselmi Cantuariensis Archepiscopi Opera Omnia, abbreviated here as S., followed by (when needed) the volume and the page numbers. Latin terms in brackets or parentheses have been romanized to current orthography. All citations of the Fragments are the author’s translations from the Ein neues unvollendetes Werk des heilige Anselm von Canterbury, henceforth abbreviated as u.W.]

Anselm references Augustine’s On the Holy Trinity, but as a whole work, giving no specific references. Clearly, Augustine was a major influence on Anselm’s thought, but that is in itself rather unremarkable, since practically all of his contemporaries fit in one way or another into the broad stream of the Augustinian tradition. As Southern summarizes the issues: “[T]he ambivalence of Anselm’s relations to St. Augustine remains one of the mysteries of his mind and personality. Augustine’s thought was the pervading atmosphere in which Anselm moved; but he was never content merely to reproduce Augustine.” (1963, 32)

In fact, one of the most important features of Anselm’s work is its originality. As Southern has also pointed out, this originality was not confined to the treatises and dialogues. In his more devotional prayers and meditations, Anselm adapted traditional forms to new content, (1963, 34-47) “open[ing] the way which led to the Dies Irae, the Imitatio Christi, and the masterpieces of later medieval piety.” (1963, 47) Although clearly indebted to an Augustinian (neo)-Platonic tradition often termed “Christian philosophy,” Anselm’s originality clearly furthered and expanded that tradition, and prepared the way for later Scholasticism. The term “Christian philosophy” was used in a variety of senses, particularly within and to denote the Augustinian tradition, and was applied to Anselm’s work by numerous interpreters. A set of debates, which gave rise to a sizable literature, and which are still to some extent being continued today, took place in Francophone circles (spreading to German, Italian, Spanish, and English-speaking circles in later years) in the early 1930s, about the nature and possibility of “Christian philosophy.” One of the main participants, Etienne Gilson, in fact used Anselm’s formula fides quaerens intellectum several times as one of the definitions of Christian philosophy.

Anselm’s work was influential for some of his contemporaries, and has continued to exercise influence in varying ways on philosophers and theologians to the present day. The so-called “ontological argument” has had numerous critics, defenders, and adaptors philosophically or theologically notable in their own right, among them St. Bonaventure, St. Thomas Aquinas, Descartes, Gassendi, Spinoza, Malebranche, Locke, Leibniz, Kant, Hegel, and an even greater number in the last century, not least of which were Charles Hartshorne, Etienne Gilson, Maurice Blondel, Martin Heidegger, Karl Barth, Norman Malcolm, and Alvin Plantinga. However, the “argument”(s) discussed in this literature are frequently not precisely what is found in Anselm’s texts, and a sizable literature has developed addressing that very issue.

Argument(s) for God’s being or existence form only a small portion of Anselm’s considerable and complex work, and his influence has been much wider and deeper than originating one perennial line of philosophical investigation and discussion. In his own time, he had several gifted students, among them Anselm of Laon, Gilbert Crispin, Eadmer (writer of the Vita Anselmi), Alexander (writer of the Dicta Anselmi), and Honorius Augustodunensis. His works were copied and disseminated in his lifetime, and exercised an influence on later Scholastics, among them Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham. For further discussion of Anselm’s influence, cf. Châtillon, 1959, Southern, 1963, Rovighi, 1964, Hopkins, 1972, and Fortin, 2001.

3. Methodology: Faith and Reason

The extent to which Anselm’s work, and which portions of it, ought to be considered to be philosophy or theology (or “philosophical theology,” “Christian philosophy,” and so forth) is a long debated question. The answers (and their rationales) depend considerably on one’s conceptions of philosophy and theology and their distinction and interaction. These admittedly important issues are set aside here in order to focus on three key features of Anselm’s work: Anselm’s pedagogical motivation and his intended audience; the notion of faith seeking understanding (fides quaerens intellectum); and Anselm’s stylistics and dialectic.

Anselm provides a paradigmatic account of the pedagogical motive structuring his works in theMonologion’s Prologue.

Some of the brothers have often and earnestly entreated me to set down in writing for them some of the matters I have brought to light for them when we spoke together in our accustomed discourses, about how the divine essence ought to be meditated upon and certain other things pertaining to that sort of meditation, as a kind of model for meditation…. They prescribed this form for me: nothing whatsoever in these matters should be made convincing [persuaderetur] by the authority of Scripture, but whatsoever the conclusion [finis], through individual investigations, should assert…the necessity of reason would concisely prove [cogeret], and the clarity of truth would evidently show that this is the case. They also wished that I not disdain to meet and address [obviare] simpleminded and almost foolish objections that occurred to me. (S. v. 1, p.7)

The original audience for his writings was fellow Benedictine monks seeking a fuller understanding of the Christian faith and asking that Anselm provide an articulation of it in a form quite different than those typical and traditional of their time, namely, where such theological discussions were carried out primarily through citation and interpretation of Scripture and patristic authorities. Anselm expresses this pedagogical motive again in the Cur Deus Homo: “I have often and most earnestly been asked by many, in speech and in writing, to commit in writing to posterity [memoriae. . commendem] reasonable answers [rationes] I am accustomed to give to those asking about a certain question of our faith.” (S. v. 2, p.47)

The goal of Anselm’s treatises is not to provide a philosophical substitute for the Christian faith, nor to rationalize or systematize it solely in the light of natural reason. Rather, in the cases of the Monologionand Proslogion, he aims to treat meditatively, by reason’s resources, central aspects of the Christian faith, namely, as he puts it in the Proslogion’s Prologue: “that God truly is, and that he is the supreme good needing no other, and that he is what all things need so that they are and so that they are well, and whatever else we believe about the divine substance.” (S., v. 1, p. 93) In the other treatises (excepting theDe Grammatico, which he explicitly states to be for “beginners in dialectic,” and that it “pertains to a different subject matter than [Sacred Scripture],” S., v.1, p. 173), Anselm concerns himself with other important, and often interrelated, aspects of the Christian faith, developing the arguments through reasoning, rather than through explicit reliance on Scriptural or patristic authority in the course of argumentation. Over the course of his career, Anselm’s intended audience expands considerably, however, particularly as he became involved in controversy over the Trinity that culminated in hisEpistola de Incarnatione Verbi and Cur Deus Homo.

The Proslogion’s Prologue provides a somewhat different, but clearly related motive for its production. After the Monologion, Anselm writes: “considering that that work was constructed from an interlinking [concatenatione] of many arguments, I began to wonder if perhaps a single argument [unum argumentum] that needed nothing other than itself alone for proving itself.” (S., v. 1, p. 93) Once he had uncovered this unum argumentum (“single argument”) after great effort and difficulty, Anselm wrote about it and several other related topics, in the interest of sharing the joy it had brought him, or at least pleasing another who would read it (alicui legenti placiturum).

Precisely what this single argument consists of has been a subject of considerable scholarly debate. A fairly common but clearly incorrect interpretation of the “single argument” takes it as referring only to the proof for God’s existence or being in Chapter 2, or at most Chapters 2-4. At the other extreme, some commentators take the single argument to be the entirety of the Proslogion. A third, intermediary position argues that the unum argumentum is the entirety of the Proslogion, minus the last three chapters, for two reasons: 1) Anselm calls the last three chapters coniectationes; 2) Anselm says in the prooemium that he wrote the Proslogion about the argument itself (de hoc ipso) and about several other things (et de quibusdam aliis).

As Anselm explains to his interlocutor Boso, his writing the De Conceptu Virginali is motivated by a purpose similar to that of the Proslogion, reexamining and rearticulating topics previously addressed in other works.

For I am certain that when you read in the Cur Deus Homo. . . that, besides the one I set down there, another reason can be glimpsed [posse uideri], how God took on humanity without sin from the sinful mass of the human race, your most studious mind will be driven not a little to asking what this reason is. Accordingly, I feared that I would appear unjust to you if I conceal what I think on this [quod inde mihi videtur] from your enjoyment [dilectioni tuae]. (S., v. 2, p. 139)

The prologue to the three connected dialogues (De Veritate, De Libertate Arbitrii, De Casu Diaboli) does not indicate conclusively whether they were written to answer specific requests of the monks. Clearly, however, they treat matters of both theological and philosophical interest arising out of reflection and discussion on Christian faith, life, and thought.

Fides quaerens intellectum, “faith seeking understanding” was the Proslogion’s original title and is an apt designation for Anselm’s philosophical and theological projects as a whole. Anselm begins from, and never leaves the standpoint of a committed and practicing Catholic Christian, but this does not mean that his philosophical work is thereby vitiated as philosophy by operating on the basis of and within the confines of theological presuppositions. Rather, Anselm engages in philosophy, employing reasoning rather than appeal to Scriptural or patristic authority in order to establish the doctrines of the Christian faith (which, as a faithful and practicing believer, he takes as already established) in a different, but possible way, through the employment of reason. Faith seeking understanding goes beyond simply establishing faith’s doctrines, however, precisely because it seeks understanding, the rational intelligibility (as far as is possible) of the doctrines.

Anselm does cite Scripture at certain points in his work, as well as “what we believe” (quod credimus), but attention to his texts indicates that he does not rely on scriptural or doctrinal authority directly to resolve problems or to provide starting points for his reasoning. In some cases, he has the student or his own questioning voice (as in Proslogion, Chapter 8) bring up Scriptural passages of truths of Christian doctrine in order to raise problems that require a rational resolution. In other cases (as in De Concordia, Book 1 Chapter 5), he does use Scriptural passages as starting points for arguments, but for erroneous arguments that he then criticizes. In yet other cases, Anselm brings up Scripture precisely to explain how certain passages or expressions should be rightly understood (as in the De Casu Diaboli, explaining how God causing evil should be understood). Lastly, Anselm cites Scripture after the course of his argument in order to reconnect the rational argumentation with Christian revelation (as in Proslogion, Chapter 16, where Anselm’s previous reasoning culminates in God “inhabiting” an “inaccessible light”). For discussion of Anselm and Scripture, cf. Barth, 1960, Tonini, 1970, and Henry, 1962.

In his actual exercise of reason, Anselm displays both confidence in reason’s capacity for providing understanding to faith, and awareness of the limitations human reason’s exercise eventually runs into and becomes aware of. For instance, in Proslogion, Chapter 15, he concludes that God is not only that than which nothing greater can be thought, but something greater than can be thought. Another important aspect of Anselm’s fides quaerens intellectum is that, in the Monologion, reason is employed by one who “disputes and investigates with himself things he had not previously taken notice of [non animadvertisset],” (S., v. 1, p. 8) and in the Proslogion, one “striving to raise his mind to the contemplation of God, and seeking to understand what he believes.” (S., v. 1, p. 94)

Despite Anselm’s deliberate employment of reason as a means to the truth about both the natural and the supernatural order, his rationalism is a mitigated one. Monologion Chapter 1 exemplifies this. Anselm’s assessment is that one could persuade oneself of the truths argued for in the Monologion by the use of one’s reason, but Anselm hastens to add: “I wish it to be understood [accipi] that, even if a conclusion is reached [concludatur] seemingly as necessary [quasi necessarium] from reasons that seem good to me, it is not that it is entirely [omnino] necessary, but only that for the current time [interim] it be said to be able to appear necessary.” (S., v. 1, p.14)

Chapter 64 of the Monologion provides another important discussion of the use of reason and argument. Anselm distinguishes between being able to understand or explain that something is true or that something exists, and being able to understand or explain how something is true. Since the divine substance, the triune God is ultimately beyond the capacities of human understanding, reason, or more precisely the reasoning human subject, must recognize both the limits and the capacities of reason.

I think that for someone investigating an incomprehensible matter it ought to be sufficient, if by reasoning towards it, he arrives at knowing that it most certainly does exist, even if he is unable to go further by use of the intellect [penetrare. . . intellectu] into how it is this way. Nor for that reason should we withhold the certainty of faith from those things that are asserted through necessary proofs [probationibus], and that are inconsistent with no other reason, if because of the incomprehensibility of their natural sublimity they do not allow themselves [non patiuntur] to be explained. (S., v. 1, p. 75)

Anselm is not skeptically questioning or undermining the capacities of reason and argumentation. Not every possible object the intellect attempts to engage with presents such problems, but only God. Accordingly, although a completely full and exhaustively systematic account cannot be provided of the divine substance, this does not undermine the certainty of what reason has been able to determine.

Stylistically, Anselm’s treatises take two basic forms, dialogues and sustained meditations. The former represent pedagogical discussions between a fairly gifted and inquisitive pupil and a teacher. In the latter, Anselm provides, as noted earlier, models of meditation, but the model differs considerably from theMonologion to the Proslogion, for in the first treatise, Anselm aims to provide a model of a person meditating, or (using Aristotle’s conception) engaging in dialectic with himself, while in the second case, the person addresses himself to the very God that he is attempting to comprehend as best as human capacities allow.

In the dialogue Cur Deus Homo, a student, Boso, “my brother and most beloved son” (S., v. 2, p. 139) is called by name. In the majority of the dialogues, the student and teacher are not named; it is clear, however, that the teacher represents Anselm and presents Anselm’s doctrines. The De Conceptu Virginali and the De Concordia are not written in the same dialogue form as the other treatises, but they are dialogical in their narrative voice(s), since Anselm addresses himself to another person (in the De Conceptu Virginali to Boso), articulating possible problems and objections his reader might make in order to address them.

The dialogue form serves a pedagogical purpose and reflects the project of fides quaerens intellectum, exemplified well by this passage from the De Casu Diaboli: “[L]et it not weary you to briefly reply to my silly questioning [fatuae interrogationi], so that I might know how I should respond to someone asking me the very same thing. Indeed, it is not always easy to respond wisely [sapienter] to someone who is asking foolishly [insipienter].” (S., v. 1, p. 275)

Interestingly, it appears that a recurring problem for Anselm was his treatises being copied and circulated without his authorization and before their final and finished state. He asserts this to be the case with the three connected dialogues and the Cur Deus Homo.

The following sections provide discussions of, and excerpts from, many of Anselm’s key works. With the exception of the Proslogion, Monologion, and Cur Deus Homo, the works are examined in chronological order (as best as we know it). These three works are discussed first and in this order because the Proslogion has garnered the most attention from philosophers (more than the earlierMonologion, with which it shares similar aims and content) and the Cur Deus Homo likewise has garnered more attention from theologians than the earlier three dialogues “pertaining to study of Sacred Scripture” (S., v.1, p. 173) (the De Veritate, De Libertate Arbitrii, and De Casu Diaboli).

4. The Proslogion

In the Proslogion, Anselm intended to replace the many interconnected arguments from his previous and much longer work, the Monologion, with a single argument. Since the unum argumentum is supposed to prove not only that God exists, but other matters about God as well, as noted above, there is some scholarly controversy as to exactly what the argument is in the Proslogion’s text. Clearly, the so-called “ontological argument” for God’s existence in Chapter 2 plays a central role. It must be pointed out that Anselm nowhere uses the term “ontological argument,” nor in fact do the critics or proponents of the argument until Kant’s time. It has unfortunately become so ingrained in our philosophical vocabulary, especially in Anglophone Anselm scholarship, however, that it would be pedantic to insist on not using it at all. An interesting and sizable recent literature has developed explicitly contesting the appellation “ontological” applied to Anselm’s Proslogion proof(s) of God’s being or existence, a partial bibliography of which is provided in McEvoy, 1994.

Noting that God is believed to be something than which nothing greater can be thought (quo maius cogitari non potest), Anselm asks whether such a thing exists, since the Fool of the Psalms has said in his heart that there is no God.

But certainly that very same Fool, when he hears this very expression I say [hoc ipsum quod dico]: “something than which nothing greater can be thought,” understands what he hears; and what he understands is in his understanding [in intellectu], even if he does not understand that thing to exist. For it is one thing to be in the understanding, and another to understand a thing to exist. . . . . Therefore even the fool is compelled to admit [convincitur] that there is in his understanding something than which nothing greater can be thought, since when he hears this he understands it, and whatever is understood is in the understanding. And certainly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the understanding alone. For if it is in the intellect alone [in solo intellectu], it can be thought to also be in reality [in re], which is something greater. If, therefore, that than which a greater cannot be thought is in the intellect alone, that very thing than which a greater cannot be thought is that than which a greater can be thought. But surely that cannot be. Therefore, without a doubt, something than which a greater cannot be thought exists [exsistit] both in the understanding and in reality. (S., v. 1, p. 101-2)

In Chapter 3, Anselm continues the argumentation, providing what some commentators take to be a second ontological argument.

And, it so truly exists that it cannot be thought not to be. For, a thing, which cannot be thought not to be (which is greater than what cannot be thought not to be), can be thought to be. So, if that than which a greater cannot be thought can be thought not to be, that very thing than which a greater cannot be thought is not that than which a greater cannot be thought, which cannot be compatible [convenire, i.e. with the thing being such]. Therefore, there truly is something than which a greater cannot be thought, and it cannot be thought not to be. (S., p. 102-3)

Addressing himself to God, Anselm explains why God cannot be thought not to exist, indicating why God uniquely has this status. “[I]f some mind could think something better than you, the creature would ascend over the Creator, and would engage in judgment about the Creator, which is quite absurd. And anything else whatsoever other than yourself can be thought not to exist. For you alone are the most true of all things, and thus you have being to the greatest degree [maxime], for anything else is not so truly [as God], and for this reason has less of being.” (S., p. 103) This raises a puzzle, however. Why does the Fool not only doubt whether God exists, but assert that there is no God? One possible, but rather circular answer is provided at the end of Chapter 3. “Why else, except because he is stupid and a fool?” (S., p. 103) As Anselm knows, however, that does not really answer the question. Chapter 4 provides an answer. The Fool both does and does not think [cogitare] that God does not exist, since there are two senses of “think”:

A thing is thought of in one way when one thinks of the word [vox] signifying it, in another way when what the thing itself is is understood. Therefore, in the first way it can be thought that God does not exist, but in the second way not at all. Indeed no one who understands that which God is can think that God is not, even though he says these words in his heart, either without any signification or with some other signification not properly applying to God [aliqua extranea significatione]. (S., p. 103-104)

Proslogion Chapters 5-26 deal progressively with the divine attributes, 5-23 either continuing or building off of the argument, and 24-26 being connected conjectures about God’s goodness. In Chapter 5, Anselm deduces attributes of God from the same “than which nothing greater can be thought” he used in Chapters 2-4.

What then are you, Lord God, that than which nothing greater can be thought? But what are you if not that which is the greatest of all things, who alone exists through himself, who made everything else from nothing? For whatever is not this, is less than what can be thought. But this cannot be thought about you. For what good is lacking to the supreme good, through which every good thing is? And so, you are just, truthful, happy, and whatever it is better to be than not to be. (S., p. 104)

These attributes of God, what it is better to be than not to be, are filled out in Chapter 6 (percipient, omnipotent, merciful, impassible), Chapter 11 (living, wise, good, happy, eternal), and Chapter 18 (an unity).

In Chapter 18, Anselm argues from God’s superlative unity to the unity of his attributes. “[Y]ou are so much a kind of unity [unum quiddam] and identical to yourself, that you are dissimilar to yourself in no way; indeed, you are that very unity, divisible by no understanding. Therefore, life and wisdom and the other [attributes] are not parts of you but all of them are one, and each of them is entirely what you are, and what the other [attributes] are.” (S., p. 115)

In Chapter 23, he employs this notion of superlative unity to explain how God can be a Trinity, indicating that all of the persons of the Trinity share equally and completely in the divine attributes. In the divine unity, the second person of the Trinity, the Son, or the Word is coequal to the first person, “Truly, there cannot be anything other than what you are, or anything greater or lesser than you in the Word by which you speak yourself; for your Word is true [verum] in the same way that you are truthful [quomodo tu verax], and for that reason he is the very same truth as you, not other than you.” (S., p. 117) The same holds for the third person of the Trinity, which is “the one love, common to you and your Son, that is, the Holy Spirit who proceeds from both.” (S., p. 117) Accordingly, for each of the persons of the Trinity, “what any of them is individually is at the same time the entire Trinity, the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit; for, any one of them individually is not something other than the supremely simple unity and the supremely one simplicity, which cannot be multiplied or be one thing different from another.” (S., p. 117)

There are five other main matters that Anselm addresses in the Proslogion, the first three of which are sets of problems stemming from seeming incompatibilities in the divine attributes. Anselm puts these questions in Chapter 6. “How can you be perceptive [es sensibilis] if you are not a body? How can you be omnipotent, if you cannot do everything? How can you be merciful and impassible at the same time?” (S., p. 104) Anselm deals with the first briefly in Chapter 6, proposing that perceiving is knowing (cognoscere) or aimed at knowing (ad cognoscendum), so that God is supremely perceptive without knowing things through the type of sensibility human beings and animals have.

The argumentation of Chapter 7 is particularly important. There are things that God cannot do, for instance lying, being corrupted, making what is true to be false or what has been done to not be done. It seems that a truly omnipotent being ought to be able to do these things. To be able to do such things, Anselm suggests, is not really to have a power (potentia), but really a kind of powerlessness (impotentia). “For one who can do these things, can do what is not advantageous to oneself and what one ought not do. The more a person can do these things, the more adversity and perversity can do against that person, and the less that person can do against these.” (S., p. 105) So, one who does these things does them through powerlessness, through having one’s agency subjected to that of something other, rather than through one’s power. This, as Anselm explains, relies on an inexact manner of speaking, where one expresses powerlessness or inability as a kind of power or ability

In Chapters 8-11, through a longer and more sustained argument, Anselm answers the third question explaining how God can be both merciful and just at the same time. The explanation rests on God’s mercy stemming from his goodness, which is not ultimately something different from God’s justice, and which can be reconciled with it. Anselm concludes in Chapter 12: “But certainly, whatever you are, you are not through another but through yourself. Accordingly, you are the very life by which you live, and the wisdom by which you are wise, and the goodness by which you are good to good people and bad people; and likewise with similar attributes.” (S., p. 110) For God to be merciful to, forgive, and therefore not render justice to all transgressors, or likewise for God to not extend mercy, forgive, and therefore render justice to all transgressors would be for God to be something lesser than He is. It is, in effect, greater to be able to be just and merciful at the same time, which is possible for God precisely because justice and goodness coincide only in God. At the same time, Anselm concedes that when it comes to understanding precisely why God mercifully forgives of justly rendered judgment in a particular case is beyond our human capacities. For further discussion of Chapters 8-11, cf. Bayart, 1937, Corbin, 1988, and Sadler, 2006.

The fourth main issue, discussed in Chapters 14-17, has to do with our limited knowledge of God, which stems both from human sinfulness and God’s dazzling splendor. Again, as in Chapter 4, one can say that something is and is not the case at the same time, because it is being said in different and distinguishable ways. “If [my soul] did not see you [God], then it did not see the light or the truth. But, is not the truth and the light what it saw and yet did it still not yet see you, since it saw you only in a certain way [aliquatenus] but did not see you exactly as you are [sicuti es]?” (S., p. 111)

The reason the human soul does not see God directly is twofold, stemming both from finite human nature and from infinite divine nature. “But certainly [the human mind] is darkened in itself, and it is dazzled [reverbetur] by you. It is obscured by its own shortness of view [sua brevitate], and it is overwhelmed by your immensity. Truly it is restricted [contrahitur] in by its own narrowness, and it is overcome [vincitur] by your grandeur.” (S., p. 112) For this reason, in Chapter 15, Anselm concludes that God is in fact “greater than can be thought” (maior quam cogitari potest).

Finally, in Chapters 18-21, Anselm discusses God’s eternity. Anselm first indicates that God’s eternity is such that God is entirely present whenever and wherever God is, which is to say everywhere and at all times. Then, in Chapter 19, he begins to articulate the implications of God’s eternity more fully, ultimately leading into a transformation of perspective. Just as it is not the case that there is eternity and God happens to be in and is therefore eternal, since the reality is that God is eternity itself, God is not in every time or place, but rather everything, all times and places, is in God, that is, in God’s eternity.

5. Gaunilo’s Reply and Anselm’s Response

Gaunilo, a monk from the Abbey of Marmoutier, while noting the value of the remainder of theProslogion, attacked its argument for God’s existence on several counts. His arguments prefigure many arguments made by later philosophers against ontological arguments for God’s existence, and Anselm’s responses provide additional insight into the Proslogion argument. Gaunilo makes four main objections, and in each case, Gaunilo transposes Anselm’s “that than which nothing greater can be thought” into “that which is greater than everything else that can be thought.”

Gaunilo asserts that an additional argument is needed to move from this being having been thought to it being impossible for it not to be. “It needs to be proven to me by some other undoubtable argument that this being is of such a sort that as soon as it is thought its undoubtable existence is perceived with certainty by the understanding.” (S., v. 1, p. 126) He brings up this need for a further, unsupplied, argument twice more in his Reply, and in the last instance discusses what is really at issue. The Fool can say: “[W]hen did I say that in the truth of the matter [rei veritate] there was such a thing that is ‘greater than everything?’ For first, by some other completely certain argument, some superior nature must be proven to exist, that is, one greater or better than everything that exists, so that from this we could prove all the other things that cannot be lacking to what is greater or better than everything else.” (S., p. 129)

A second problem is whether one can actually understand what is supposed to be understood in order for the argument to work because God is unlike any creature, anything that we have knowledge or a conception of . “When I hear ‘that which is greater than everything that can be thought,’ which cannot be said to be anything other than God himself, I cannot think it or have it in the intellect on the basis of something I know from its species or genus. . . . For I neither know the thing itself, nor can I form an idea of it from something similar.” (S., p. 126-7)

Gaunilo continues along this line, arguing that the verbal formula employed in the argument is merely that, a verbal formula. The formula cannot really be understood, so it does not then really exist in the understanding. The signification or meaning of the terms can be thought, “but not as by a person who knows what is typically signified by this expression [voce], i.e. by one who thinks it on the basis of a thing that is true at least in thought alone.” (S., p. 127) Instead, what is actually being thought, according to Gaunilo, is vague. The signification or meaning of the terms is grasped only in a groping manner. “[I]t is thought as by one who does not know the thing and simply thinks on the basis of a movement of the mind produced by hearing this expression, trying to picture to himself the meaning of the expression perceived.” (S., p. 127) From this, Gaunilo concludes what he takes to be a denial of one of the premises of the argument: “So much then for the notion that that supreme nature is said to already exist in my understanding.” (S., p. 127)

A third problem that Gaunilo raises is that the argument could be applied to things other than God, things that are clearly imaginary, so that, if the argument were valid, it could be used to prove much more than Anselm intended, namely falsities. Here, the example of the Lost Island is introduced. “You can no longer doubt that this island excelling [praestantiorem] all other lands truly exists somewhere in reality, this island that you do not doubt to exist in your understanding; and since it is more excellent not to be in the understanding alone but also to be in reality, so it is necessary that it exists, since, if it did not, any other land that exists in reality would be more excellent than it.” (S., p. 128)

Anselm’s responses are long, detailed, and dense. Anselm notes Gaunillo’s alteration of the terms of the argument, and that this affects the force of the argument.

You repeat often that I say that, because what is greater than everything else [maius omnibus] is in the understanding, if it is the understanding it is in reality – for otherwise what is greater than everything else would not be greater than everything else – but such a proof [probatio] is found nowhere in all of the things I have said. For, saying “that which is greater than all” and “that than which nothing greater can be thought” do not have the same value for proving that what is being talked about is in reality. (S., p. 134)Therefore if, from what is said to be “greater than everything,” what “that than which nothing greater can be thought” proves of itself through itself [de se per seipsum] cannot be proved in a similar way, you have unjustly criticized me for having said what I did not say, when this differs so much from what I did say. (S., p. 135)

In Anselm’s view, Gaunilo demands a further argument precisely because he has not understood the argument as Anselm presented it. Anselm also affirms that we can understand the meaning of the term, “that than which nothing greater can be thought,” and that it is not simply a verbal formula.

Again, that you say that, when you hear it, you are not able to think or have in your mind “that than which a greater cannot be thought” on the basis of something known from its species or genus, so that you neither know the thing itself, nor can you form an idea of it from something similar. But quite evidently the matter is and remains otherwise [aliter sese habere]. For, every lesser good, insofar as it is good, is similar to a greater good. It is apparent to any reasonable mind that by ascending from lesser goods to greater ones, from those than which something greater can be thought, we are able to infer much [multum. . .conjicere] about that than which nothing greater can be thought. (S., p. 138)

Anselm notes a similarity between the terms “ineffable,” “unthinkable,” and “that than which nothing greater can be thought,” for in each case, it can be impossible for us to think or understand the thing referred to by the expression, but the expression can be thought and understood. Earlier on, Anselm makes a distinction that sheds additional light on this distinction between thinking and understanding the expression, and thinking and understanding the thing referred to by the expression. He also employs a useful metaphor. “[I]f you say that what is not entirely understood is not understood and is not in the understanding: say, then, that since someone is not able to gaze upon the purest light of the sun does not see light that is nothing but sunlight.” (S., p. 132) We do not have to fully and exhaustively understand what a term refers to in order for us to understand the term, and that applies to this case. “Certainly ‘that than which a greater cannot be thought’ is understood and is in the understanding at least to the extent [hactenus] that these things are understood of it.” (S., p. 132)

Anselm also clarifies the scope of his argument, indicating that it applies only to God: “I say confidently that if someone should find for me something existing either in reality or solely in thought, besides ‘that than which a greater cannot be thought,’ to which the schematic framework [conexionem] of my argument could rightly be adapted [aptare valeat], I will find and give him this lost island, nevermore to be lost.” (S., p. 134)

6. The Monologion

This earlier and considerably longer work includes an argument for God’s existence, but also much more discussion of the divine attributes and economy, and some discussion of the human mind. The proof Anselm provides in Chapter 1 is one he considers easiest for a person

who, either because of not hearing or because of not believing, does not know of the one nature, greatest of all things that are, alone sufficient to itself in its eternal beatitude, and who by his omnipotent goodness gives to and makes for all other things that they are something or that in some way they are well [aliquomodo bene sunt], and of the great many other things that we necessarily believe about God or about what he has created. (S., v. 1, p. 13)

The Monologion proof argues from the existence of many good things to a unity of goodness, a one thing through which all other things are good. Anselm first asks whether the diversity of good we experience through our senses and through our mind’s reasoning are all good through one single good thing, or whether there are different and multiple good things through which they are good. He recognizes, of course, that there are a variety of ways for things to be good things, and he also recognizes that many things are in fact good through other things. But, he is pushing the question further, since for every good thing B through which another good thing A is good, one can still ask what that good thing B is good through. If goods can even be comparable as goods, there must be some more general and unified way of regarding their goodness, or that through which they are good. Anselm argues: “you are not accustomed to considering something good except on an account of some usefulness, as health and those things that conduce to health are said to be good [propter aliquam utilitatem], or because of being of intrinsic value in some way [propter quamlibet honestatem], just as beauty and things that contribute to beauty are esteemed to be a good.” (S., p. 14)

This being granted, usefulness and intrinsic values can be brought to a more general unity. “It is necessary, for all useful or intrinsically valuable things, if they are indeed good things, that they are good through this very thing, through which all goods altogether [cuncta bona] must exist, whatever this thing might be.” (S., p. 14-5) This good alone is good through itself. All other good things are ultimately good through this thing, which is the superlative or supreme good. Certain corollaries can be drawn from this. One is that all good things are not only good through this Supreme Good; they are good, that is to say they have their being from the Supreme Good. Another is that “what is supremely good [summe bonum] is also supremely great [summe magnum]. Accordingly, there is one thing that is supremely good and supremely great, i.e. the highest [summum] of all things that are.” (S., p. 15) In Chapter 2, Anselm clarifies what he means by “great,” making a point that will assume greater importance in Chapter 15: “But, I am speaking about ‘great’ not with respect to physical space [spatio], as if it is some body, but rather about things that are greater [maius] to the degree that they are better [melius] or more worthy [dignus], for instance wisdom.” (S., p. 15)

Chapter 3 provides further discussion of the ontological dependence of all beings on this being. For any thing that is or exists, there must be something through which it is or exists. “For, everything that is, either is through [per] something or through nothing. But nothing is through nothing. For, it cannot be thought [non. . .cogitari potest] that something should be but not through something. So, whatever is, only is through something.” (S., p. 15-6) Anselm considers and rejects several possible ways of explaining how it is that all things are. There could be one single being through which all things have their being. Or there could be a plurality of beings through which other beings have their being. The second possibility allows three cases: “[I]f they are multiple, then either: 1) they are referred to some single thing through which they are, or 2) they are, individually [singula], through themselves [per se], or 3) they are mutually through each other [per se invicem].” (S., p. 16)

In the first case, they are all through one single being. In the second case, there is still some single power or nature of existing through oneself [existendi per se], common to all of them. Saying that they exist through themselves really means that they exist through this power or nature which they share. Again, they have one single ontological ground upon which they are dependent. One can propose the third case, but it is upon closer consideration absurd. “Reason does not allow that there would be many things [that have their being] mutually through each other, since it is an irrational thought that some thing should be through another thing, to which the first thing gives its being.” (S., p. 16)

For Anselm three things follow from this. First, there is a single being through which all other beings have their being. Second, this being must have its being through itself. Third, in the gradations of being, this being is to the greatest degree.

Whatever is through something else is less than that through which everything else together is, and that which alone is through itself. . . . So, there is one thing that alone, of all things, is, to the greatest degree and supremely [maxime et summe]. For, what of all things is to the greatest degree, and through which anything else is good or great, and through which anything else is something, necessarily that thing is supremely good and supremely great and the highest of all things that are. (S., p. 16)

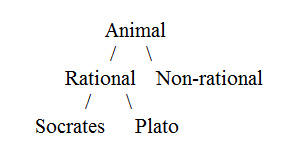

Chapter 4 continues this discussion of degrees. In the nature of things, there are varying degrees (gradus) of dignity or worth (dignitas). The example Anselm uses is humorous and indicates an important feature of the human rational mind, namely its capacity to grasp these different degrees of worth. “For, one who doubts whether a horse in its nature is better than a piece of wood, and that a human being is superior to a horse, that person assuredly does not deserve to be called a human being.” (S., p. 17) Anselm argues that there must be a highest nature, or rather a nature that does not have a superior, otherwise the gradations would be infinite and unbounded, which he considers absurd. By argumentation similar to that of the previous chapters, he adduces that there can only be one such highest nature. The scale of gradations comes up again later in Chapter 31, where he indicates that creatures’ degrees of being, and being superior to other creatures, depends on their degree of likeness to God (specifically to the divine Word).

[E]very understanding judges natures in any way living to be superior to non-living ones, sentient natures to be superior to non-sentient ones, rational ones to be superior to irrational ones. For since the Supreme Nature, in its own unique manner, not only is but also lives and perceives and is rational, it is clear that. . . what in any way is living is more alike to the Supreme Nature than that which does not in any way live; and, what in any way, even by bodily sense, knows something is more like the Supreme Nature than what does not perceive at all; and, what is rational is more like the Supreme Nature than what is not capable of reason. (S., p. 49)

Through something akin to what analytic philosophers might term a thought-experiment and phenomenologists an eidetic variation, Anselm considers a being gradually stripped of reason, sentience, life, and then the “bare being” (nudum esse) that would be left: “[T]his substance would be in this way bit by bit destroyed, led by degrees (gradatim) to less and less being, and finally to non-being. And, those things that, when they are taken away [absumpta] one by one from some essence, reduce it to less and less being, when they are reassumed [assumpta] . . . lead it to greater and greater being.” (S., p. 49-50)

In the chapters that follow, Anselm indicates that the Supreme Nature derives its existence only from itself, meaning that it was never brought into existence by something else. Anselm uses an analogy to suggest how the being of the Supreme Being can be understood.

Therefore in what way it should be understood [intelligenda est] to be through itself and from itself [per se et ex se], if it does not make itself, not arise as its own matter, nor in any way help itself to be what it was not before?. . . .In the way “light” [lux] and “to light” [lucere] and “lighting” [lucens] are related to each other [sese habent ad invicem], so are “essence” [essentia] and “to be” [esse] and “being,” i.e. supremely existing or supremely subsisting. (S., p. 20)

This Supreme Nature is that through which all things have their being precisely because it is the Creator, which creates all beings (including the matter of created beings) ex nihilo.

In Chapters 8-14, the argument shifts direction, leading ultimately to a restatement of the traditional Christian doctrine of the Logos (the “Word” of God, the Son of the Father and Creator). The argumentation starts by examination of the meaning of “nothing,” distinguishing different senses and uses of the term. Creation ex nihilo could be interpreted three different ways. According to the first way, “what is said to have been made from nothing has not been made at all.” (S., p. 23) In another way, “something was said to be made from nothing in this way, that it was made from this very nothing, that is from that which is not; as if this nothing were something existing, from which something could be made.” (S., p. 23) Finally, there is a “third interpretation. . . when we understand something to be made but that there is not something from which it has been made.” (S., p. 23)

The first way, Anselm says, cannot be properly applied to anything that actually has been made, and the second way is simply false, so the third way or sense is the correct interpretation. In Chapter 9, an important implication of creation ex nihilo is drawn out “There is no way that something could come to be rationally from another, unless something preceded the thing to be made in the maker’s reason as a model, or to put it better a form, or a likeness, or a rule.” (S., p. 24) This, in turn implies another important doctrine: “what things were going to be, or what kinds of things or how the things would be, were in the supreme nature’s reason before everything came to be.” (S., p. 24) In subsequent chapters, the doctrine is further elaborated, culminating in this pattern being the utterance (locutio) of the supreme essence and the supreme essence, that is to say the Word (verbum) of the Father, while being of the same substance as the Father.

Chapter 15-28 examine, discuss, and argue for particular attributes of God, 15-17 and 28 being of particular interest. Chapter 15 is devoted to the matter of what can be said about the divine substance. Relative terms do not really communicate the essence of the divine being, even including expressions such as “the highest of all” (summa omnium) or “greater than everything that has been created by it” (maior omnibus . . .) “For if none of those things ever existed, in relation to which [God] is called “the highest” and “greater,” it would be understood to be neither the highest nor greater. But still, it would be no less good on that account, nor would it suffer any loss of the greatness of its essence. And this is obvious, for this reason: whatever may be good or great, this thing is not such through another but by its very self.” (S., p. 28)

There are still other ways of talking about the divine substance. One way is to say that the divine substance is “whatever is in general [omnino] better that what is not it. For, it alone is that than which nothing is better, and that which is better than everything else that is not what it is.” (S., p. 29) Given that explanation, while there are some things that it is better for certain beings to be rather than not to be, God will not be those things, but only what it is absolutely better to be than not to be. So, for instance, God will not be a body, but God will be wise or just. Anselm provides a partial listing of the qualities or attributes that do express the divine essence: “living, wise, powerful and all-powerful, true, just, happy, eternal, and whatever in like wise it is absolutely better to be than not to be.” (S., p. 29)

Anselm raises a problem in Chapter 16. Granted that God has these attributes, one might think that all that is being signified is that God is a being that has these attributes to a greater degree than other beings, not what God is. Anselm uses justice as the example, which is fitting since it is usually conceived of as something relational. Anselm first sets out the problem in terms of participation in qualities. “[E]verything that is just is just through justice, and similarly for other things of this sort. Accordingly, that very supreme nature is not just unless through justice. So, it appears that by participation in the quality, namely justice, the supremely good substance can be called just.” (S., p. 30) And this reasoning leads to the conclusion that the supremely good substance “is just through another, and not through itself.” (S., p. 30)

The problem is that God is what he is through himself, while other things are what they are through him. In the case of each divine attribute, as in the later Proslogion, God having that attribute is precisely that attribute itself, so that for instance, God is not just by some standard or idea of justice extrinsic to God himself, but rather God is God’s own justice, and justice in the superlative sense. Everything else canhave the attribute of justice, whereas God is justice. This argument can be extended to all of God’s attributes What is perceived to have been settled in the case of justice, the intellect is constrained by reason to judge [sentire] to be the case about everything that is said in a similar way about that supreme nature. Whichever of them, then, is said about the supreme nature, it is not how [qualis] nor how much [quanta] [the supreme nature has quality] that is shown [monstratur] but rather what it is. . . .Thus, it is the supreme essence, supreme life, supreme reason, supreme salvation [salus], supreme justice, supreme wisdom, supreme truth, supreme goodness, supreme greatness, supreme beauty, supreme immortality, supreme incorruptibility, supreme immutability, supreme happiness, supreme eternity, supreme power [potestas], supreme unity, which is nothing other than supreme being, supremely living, and other things in like wise [similiter]. (S., p. 30-1)

This immediately raises yet another problem, however, because this seems like a multiplicity of supreme attributes, implying that each is a particularly superlative way of being for God, suggesting that God is in some manner a composite. Instead, in God (not in any other being) each of these is all of the others. God’s being alone, as Chapter 28 argues, is being in an unqualified sense. All other beings, since they are mutable, or because they can be understood to have come from non-being, “barely (vix) exist or almost (fere) do not exist.” (S., p. 46)

Chapters 29-48 continue the investigation of the generation of the “utterance” or Word, the Son, from the Father in the divine economy, and 49-63 expand this to discussion of the love between the Father and the Son, namely the Holy Spirit, equally God as the Father and Son. 64-80 discuss the human creature’s grasp and understanding of God. Chapter 31 is of particular interest, and discusses the relationship between words or thoughts in human minds and the Word or Son by which all things were created by the Father. A human mind contains images or likenesses of things that are thought of or talked about, and a likeness is true to the degree that it imitates more or less the thing of which it is likeness, so that the thing has a priority in truth and in being over the human subject apprehending it, or more properly speaking, over the image, idea, or likeness by which the human subject apprehends the thing. In the Word, however, there are not likenesses or images of the created things, but instead, the created things are themselves imitations of their true essences in the Word.

The discussion in Chapters 64-80, which concludes the Monologion, makes three central points. First, the triune God is ineffable, and except in certain respects incomprehensible, but we can arrive at this conclusion and understand it to some degree through reason. This is because our arguments and investigations do not attain the distinctive character (proprietatem) of God. That does not present an insurmountable problem, however.

For often we talk about many things that we do not express properly, exactly as they really are, but we signify through another thing what we will not or can not bring forth properly, as for instance when we speak in riddles. And often we see something, not properly, exactly how the thing is, but through some likeness or image, for instance when we look upon somebody’s face in a mirror. Indeed, in this way we talk about and do not talk about, see and do not see, the same thing. We talk about it and see it through something else; we do not talk about it and see it through its distinctive character [proprietatem]Now, whatever names seem to be able to be said of this nature, they do not so much reveal it to me through its distinctive character as signify it [innuunt] to me through some likeness. (S., v. 1, p. 76)

Anselm uses the example of the divine attribute of wisdom. “For the name ‘wisdom’ is not sufficient to reveal to me that being through which all things were made from nothing and preserved from [falling into] nothing.” (S., p. 76)

The outcome of this is that all human thought and knowledge about God is mediated through something. Likenesses are never the thing of which they are a likeness, but there are greater and lesser degrees of likeness. This leads to the second point. Human beings come closer to knowing God through investigating what is closer to him, namely the rational mind, which is a mirror both of itself and, albeit in a diminished way, of God.

[J]ust as the rational mind alone among all other creatures is able to rise to the investigation of this Being, likewise it is no less alone that through which the rational mind itself can make progress towards investigation of that Being. For we have already come to know [jam cognitum est] that the rational mind, through the likeness of natural essence, most approaches that Being. What then is more evident than that the more assiduously the rational mind directs itself to learning about itself, the more effectively it ascends to the knowledge [cognitionem] of that Being, and that the more carelessly it looks upon itself, the more it descends from the exploration [speculatione] of that Being? (S., v. 1, p. 77)

Third, to be truly rational involves loving and seeking God, which in fact requires an effort to remember and understand God. “[I]t is clear that the rational creature ought to expend all of its capacity and willing [suum posse et velle] on remembering and understanding and loving the Supreme Good, for which purpose it knows itself to have its own being.” (S., p. 79)

7. Cur Deus Homo

The Monologion and Proslogion (although often only Chapters 2-4 of the latter) are typically studied by philosophers. The Cur Deus Homo (Why God Became Man) is more frequently studied by theologians, particularly since Anselm’s interpretation of the Atonement has been influential in Christian theology. The method, however, as in his other works, is primarily a philosophical one, attempting to understand truths of the Christian faith through the use of reasoning, granted of course, that this reasoning is applied to theological concepts. Anselm provides a twofold justification for the treatise, both responding to requests “by speech and by letter.” The first is for those asking Anselm to discuss the Incarnation, providing rational accounts (rationes) “not so that through reason they attain to faith, but so that they may delight in the understanding and contemplation of those things they believe, and so that they might be, as much as possible, ‘always ready to satisfy all those asking with an account [rationem] for those things for which’ we ‘hope.’” (S., v. 2, p. 48)

The second is for those same people, but so that they can engage in argument with non-Christians. As Anselm says, non-believers make the question of the Incarnation a crux in their arguments against Christianity, “ridiculing Christian simplicity as foolishness, and many faithful are accustomed to turn it over in their hearts.” (S., p. 48) The question simply stated is this: “by what reason or necessity was God made man, and by his death, as we believe and confess, gave back life to the world, when he could have done this either through another person, either human or angelic, or through his will alone?” (S., p. 48)

In Chapter 3, Anselm’s interlocutor, his fellow monk and student Boso, raises several specific objections made by non-Christians to the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation: “we do injustice and show contempt [contumeliam] to God when we affirm that he descended into a woman’s womb, and that he was born of woman, that he grew nourished by milk and human food, and – so that I can pass over many other things that do not seem befitting to God– that he endured weariness, hunger, thirst, lashes, and the cross and death between thieves.” (S., v. 2, p. 51)

Anselm’s immediate response mirrors the structure of the Cur Deus Homo. Each of the points he makes are argued in fuller detail later in the work.

For it was fitting that, just as death entered into the human race by man’s disobedience, so should life be restored by man’s obedience. And, that, just as the sin that was the cause of our damnation had its beginning from woman, so the author of our justice and salvation should be born from woman. And, that the devil conquered man through persuading him to taste from the tree [ligni], should be conquered by man through the passion he endured on the tree [ligni]. (S., p. 51)

The first book (Chapters 1-25), produces a lengthy argument, involving a number of distinctions, discussions about the propriety of certain expressions and the entailments of willing certain things. Chapters 16-19 represent a lengthy digression involving questions about the number of angels who fell or rebelled against God, whether their number is to be made up of good humans, and related questions. The three most important parts of the argument take the form of these discussions: the justice and injustice of God, humans, and the devil; the entailments of the Father and the Son willing the redemption of humanity; the inability of humans to repay God for their sins.

Anselm distinguishes, as he does in the earlier treatise De Veritate, different ways in which an action or state can be just or unjust, specifically just and unjust at the same time, but not in the same way of looking at the matter. “For, it happens sometimes [contingit] that the same thing is just and unjust considered from different viewpoints [diversis considerationibus], and for this reason it is adjudged to be entirely just or entirely unjust by those who do not look at it carefully.” (S., p. 57) Humans are justly punished by God for sin, and they are justly tormented by the devil, but the devil unjustly torments humans, even though it is just for God to allow this to take place.“In this way, the devil is said to torment a man justly, because God justly permits this and the man justly suffers it. But, because a man is said to justly suffer, one does not mean that he justly suffers because of his own justice, but because he is punished by God’s just judgment.” (S., p. 57)

Not only distinguishing between different ways of looking at the same matter is needed, but also distinguishing between what is directly willed and what is entailed in willing certain things. On first glance, it could seem that God the Father directly wills the death of Jesus Christ, God the Son, or that the latter wills his own death. Indeed something like this has to be the case, because God does will the redemption of humanity, and this comes through the Incarnation and through Christ’s death and resurrection. According to Anselm, Christ dies as an entailment of what it is that God wills. “For, if we intend to do something, but propose to do something else first through which the other thing will be done, when what we chose to be first is done, if what we intend comes to be, it is correctly said to be done on account of the other…” (S., p. 62-3) Accordingly, what God willed (as both Father and Son) was the redemption of the human race, which required the death of Christ, and required this “not because the Father preferred the death of the Son over his life, but because the Father was not willing to restore the human race unless man did something as great as that death of Christ was.” (S., p. 63) As Anselm goes on to explain, the determination of the Son’s will then takes place within the structure of the Father’s will. “Since reason did not demand that another person do what he could not, for that reason the Son says that he wills his own death, which he preferred to suffer rather than that the human race not be saved.” (S., p. 63-4) What was involved in Christ’s death, therefore, was actually obedience on the part of the Son, following out precisely what was entailed by God’s willing to redeem humanity. The central point of the argument is then making clear why the redemption of humanity would have to involve the death of Christ. Articulating this, Anselm begins by discussing sin in terms of what is due or owed to (quod debet) God.

Sin is precisely not giving God what is due to him, namely: “[e]very willing [voluntas] of a rational creature should [debet] be subject to God’s will.” (S., p. 68) Doing this is justice or rightness of will, and is the “sole and complete debt of honor” (solus et totus honor), which is owed to God. Now, sin, understood as disobedience and contempt or dishonor, is not as simple, nor as simple to remedy, as it first appears. In the sinful act or volition, which already requires its own compensation, there is an added sin against God’s honor, which requires additional compensation. “But, so long as he does not pay for [solvit] what he has wrongly taken [rapuit], he remains in fault. Nor does it suffice simply to give back what was taken away, but for the contempt shown [pro contumelia illata] he ought to give back more than he took away.” (S., p. 68)

Anselm provides analogous examples: one endangering another’s safety ought to restore the safety, but also compensate for the anguish (illata doloris iniuria recompenset); violating somebody’s honor requires not only honoring the person again, but also making recompense in some other way; unjust gains should be recompensed not only by returning the unjust gain, but also by something that could not have otherwise been demanded.

The question then is whether it would be right for God to simply forgive humans sins out of mercy (misericordia), and the answer is that this would be unbefitting to God, precisely because it would contravene justice. It is really impossible, however, for humans to make recompense or satisfaction, that is to say, satisfy the demands of justice, for their sins. One reason for this is that one already owes whatever one would give God at any given moment. Boso suggests numerous possible recompenses: “[p]enitence, a contrite and humbled heart, abstinence and bodily labors of many kinds, and mercy in giving and forgiving, and obedience.” (S., p. 68)

Anselm responds, however: “When you give to God something that you owe him, even if you do not sin, you ought not reckon this as the debt that you own him for sin. For, you owe all of these things you mention to God.” (S., p. 68) Strict justice requires that a human being make satisfaction for sin, satisfaction that is humanly impossible. Absent this satisfaction, God forgiving the sin would violate strict justice, in the process contravening the supreme justice that is God. A human being is doubly bound by the guilt of sin, and is therefore “inexcusable” having “freely [sponte] obligated himself by that debt that he cannot pay off, and by his fault cast himself down into this impotency, so that neither can he pay back what he owed before sinning, namely not sinning, nor can he pay back what he owes because he sinned.” (S., p. 92)

Accordingly, humans must be redeemed through Jesus Christ, who is both man and God, the argument for which comes in Book II, starting in Chapter 6, and elaborated through the remainder of the treatise, which also treats subsidiary problems. The argument at its core is that only a human being can make recompense for human sin against God, but this being impossible for any human being, such recompense could only be made by God. This is only possible for Jesus Christ, the Son, who is both God and man, with (following the Chalcedonian doctrine) two natures united but distinct in the same person (Chapter7). The atonement is brought about by Christ’s death, which is of infinite value, greater than all created being (Chapter 14), and even redeems the sins of those who killed Christ (Chapter 15). Ultimately, in Anselm’s interpretation of the atonement, divine justice and divine mercy in the fullest senses are shown to be entirely compatible.

8. De Grammatico

This dialogue stands on its own in the Anselmian corpus, and focuses on untangling some puzzles about language, qualities, and substances. Anselm’s solutions to the puzzles involve making needed distinctions at proper points, and making explicit what particular expressions are meant to express. The dialogue ends with the puzzles resolved, but also with Anselm signaling the provisional status of the conclusions reached in the course of investigation. He cautions the student: “Since I know how much the dialecticians in our times dispute about the question you brought forth, I do not want you to stick to the points we made so that you would hold them obstinately if someone were to be able to destroy them by more powerful arguments and set up others.” (S., v. 1, p.168)

The student begins by asking whether “expert in grammar” (grammaticus) is a substance or a quality. The question, and the discussion, has a wider scope, however, since once that is known, “I will recognize what I ought to think about other things that are similarly spoken of through derivation [denominative].” (S., p.144)

There is a puzzle about the term “expert in grammar,” and other like terms, because a case, or rather an argument, can be made for either option, meaning it can be construed to be a substance or a quality. The student brings forth the argument.

That every expert in grammar is a man, and that every man is a substance, suffice to prove that expert in grammar is a substance. For, whatever the expert in grammar has that substance would follow from, he has only from the fact that he is a man. So, once it is conceded that he is a man, whatever follows from being a man follows from being an expert in grammar. (S., v. 1, p.144-5)

At the same time, philosophers who have dealt with the subject have maintained that it is a quality, and their authority is not to be lightly disregarded. So, there is a serious and genuine problem. The term must signify either a substance or a quality, and cannot do both. One option must be true and the other false, but since there are arguments to be made for either side, it is difficult to tell which one is false.