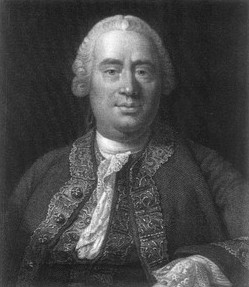

David Hume: Imagination

David Hume (1711–1776) approaches questions in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics and aesthetics via questions about our minds. For example, before addressing the epistemological question of whether we have any justification for our beliefs about unobserved states of affairs, Hume asks which of our cognitive faculties is responsible for these beliefs. Before addressing the metaphysical question, What is causal necessity (or necessary connexion)? , he asks what idea we have of a necessary connection between a cause and its effect. And before addressing the ethical question of why we are morally obligated to treat other people justly, he asks why we naturally sympathize with people whose interests suffer due to injustice. Hume tries to answer these and other questions about our minds empirically (that is, by observing himself and other people) and systematically. He calls this project his “science of man”; today, we would regard it as an amalgam of philosophy of mind, psychology and sociology.

David Hume (1711–1776) approaches questions in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics and aesthetics via questions about our minds. For example, before addressing the epistemological question of whether we have any justification for our beliefs about unobserved states of affairs, Hume asks which of our cognitive faculties is responsible for these beliefs. Before addressing the metaphysical question, What is causal necessity (or necessary connexion)? , he asks what idea we have of a necessary connection between a cause and its effect. And before addressing the ethical question of why we are morally obligated to treat other people justly, he asks why we naturally sympathize with people whose interests suffer due to injustice. Hume tries to answer these and other questions about our minds empirically (that is, by observing himself and other people) and systematically. He calls this project his “science of man”; today, we would regard it as an amalgam of philosophy of mind, psychology and sociology.

One of the main discoveries that Hume claims to make, as a scientist of man, is that “men are mightily govern’d by the imagination.” He argues that the faculty of imagination is responsible for important features both of each individual human being’s mind and of the social arrangements that human beings form collectively. Concerning each individual human being’s mind, Hume argues that the imagination explains how we can form “abstract” or “general” ideas (that is, ideas that represent categories of things); how we reason from causes to their effects, or from effects to their causes; why we tend to sympathize, or share the feelings of other people; and why we project some of our feelings onto objects in the world around us. He also argues that the imagination explains numerous “fictions” that we believe. Concerning human social arrangements, Hume argues that features of the imagination explain why we need to form governments, and shape the laws that we adopt, including those that govern the distribution of property and those that govern the passage of national authority from one monarch to the next.

This article starts by explaining Hume’s views about thought in general. It then focuses on his views about imaginative thought in particular. It explains his conception of the imagination and its relations to our other faculties of thought, highlighting the continuities and discontinuities between his views and those of his Early Modern predecessors. It then presents some of the basic functions that Hume thinks the imagination performs, and surveys some highlights of his science of man, showing how he uses the imagination’s basic functions to explain several important mental phenomena. It then examines “fictions of the imagination,” which have an important place in his science of man, and his view that whatever we can clearly imagine is possible. Lastly, it discusses the relationship between Hume’s theory of the imagination and his skepticism.

Table of Contents

- Thought, Ideas and the Copy Principle

- The Imagination and Our Other Faculties of Thought

- Five Basic Functions of the Inclusive Imagination

- Four Non-Basic Functions of the Inclusive Imagination

- Fictions of the Imagination

- Imaginability and Possibility

- The Imagination and Hume’s Skepticism

- References and Further Reading

1. Thought, Ideas and the Copy Principle

Hume writes that “men are mightily govern’d by the imagination” (T 3.2.7.2; SBN 534). And imagination is a kind of thought. To understand Hume’s views about imaginative thought, specifically, we must first examine some of his views about thought in general: his distinction between impressions and ideas; his distinction between simple and complex perceptions; and his Copy Principle. Hume’s main discussions of these topics are in A Treatise of Human Nature (hereafter, Treatise) Book 1, Part 1, Section 1; paragraphs 5–7 of Hume’s “Abstract” of the Treatise; and Section 2 of An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (hereafter, “first Enquiry”).

Hume tries to explain everything that takes place in our minds, including thought, by appealing to perceptions and their interactions. He distinguishes two kinds of perceptions: impressions and ideas (T 1.1.1.1; SBN 1–2; T Abs 5; SBN 647; and E 2.1–3; SBN 17–18). He equates having impressions with “feeling,” or first-hand experience. So, our impressions include all of the sensations, passions and emotions that we experience when we engage in sensory perception, feel painful or pleasurable sensations in our bodies, or feel passions like love and hatred. He equates having ideas with thinking: in his view, thinking about an object, or thinking that a certain state of affairs obtains, involves forming an idea that represents this object or state of affairs. The only difference that Hume sees between impressions and ideas is their degree of force and liveliness, or force and vivacity. Impressions are more forceful and lively than ideas: for example, actually feeling a pain is more forceful and lively than merely thinking about a pain. (Scholars disagree about how to interpret Hume’s talk of force and vivacity. According to some, a perception’s force and vivacity is matter of how it feels to have that perception—that is, a matter of its phenomenology. According to others, a perception’s force and vivacity is a matter of how it behaves in our minds—that is, a matter of its functional role.)

Hume also distinguishes simple and complex perceptions (T 1.1.1.2; SBN 2). This cuts across his distinction between impressions and ideas, so that there are four categories of perception altogether: simple impressions; complex impressions; simple ideas; and complex ideas. A complex perception is made up of parts. For example, when you look at a Granny Smith apple in good light, you experience an array of color-sensations; Hume would regard this array of sensations as a complex impression. When you bite into a Granny Smith apple, you experience a sensation that is made up of various taste-sensations, smell-sensations, tactile sensations of the apple’s texture on your tongue, and so forth. Again, Hume would regard this overall sensation as a complex impression. When you think about a Granny Smith apple, you form a complex idea (or less forceful perception) made up of similar parts. Suppose that we broke one of these complex perceptions up into its parts, and examined each of them individually. Perhaps we would find that some of these perceptions have parts of their own. For example, perhaps your impression of the apple’s taste is itself made up of different parts—a sweet-sensation and a tart-sensation, say. Hume thinks that this process of breaking a perception into parts, and then breaking these parts into parts, could not go on forever. Eventually, we would reach perceptions that have no parts of their own. Hume calls these perceptions simple. He holds that every perception is either simple, or is built up entirely from simple perceptions, in which case it is complex. (Hume does not explicitly distinguish simple from complex perceptions in the “Abstract” or the opening sections of the first Enquiry. Nonetheless, he continues to rely on this distinction: for example, see E 2.5–6; SBN 19, E 3.1; SBN 23 and E 7.4; SBN 62.)

Hume argues that each of your simple ideas is caused by, and exactly resembles, a simple impression that you have previously had—in other words, each of your simple ideas is an exact copy of one of your simple impressions (T 1.1.1.7–12; SBN 4–7; T Abs 6–7; SBN 647–8; E 2.4–9; SBN 18–22). Scholars often call this Hume’s Copy Principle. Since Hume thinks that every idea is either simple or complex, and that a complex idea is entirely made up of simple ones, it follows that every idea is either an exact copy of an impression, or is entirely made up of such copies. Because ideas are less forceful than impressions, Hume calls them “faint images” of our impressions.

According to Hume, then, thinking involves forming a faint image, or assembling a montage of faint images, of sensations, passions, and emotions. Since the imagination is a faculty of thought, it is a faculty by which we form such images.

2. The Imagination and Our Other Faculties of Thought

This section addresses Hume’s views about the faculty of imagination, its parts or sub-faculties, and its relationship to the two other faculties of thought that Hume distinguishes: memory and reason. The main texts on this topic are Treatise Book 1, Part 1, Section 3; Book 1, Part 3, Section 5; and Hume’s footnote to Book 1, Part 3, Section 9, Paragraph 19.

a. Two Senses of “Imagination”

In the Treatise, Hume explains that he uses the word “imagination” (and its synonym, “fancy”) in two different senses:

When I oppose the imagination to the memory, I mean the faculty, by which we form our fainter ideas. When I oppose it to reason, I mean the same faculty, excluding only our demonstrative and probable reasonings. (T 1.3.9.19n22; SBN 118n)

Some twentieth century scholars thought that these two different senses of “imagination” refer to two completely different mental faculties: a faculty of feigning or make-believe, and a faculty for apprehending real things. (For example, see Kemp Smith 1941: 459.) However, this seems to conflict with what Hume says: that both senses of “imagination” refer to “the same faculty.” Therefore, scholars in the late twentieth and early twenty first century broadly agree on the following interpretation of the two senses. In one sense, “imagination” picks out a faculty that is responsible for all of our thoughts except for memories. In this sense, the imagination includes our faculty of “reason”—by which Hume here means our faculty for carrying out “demonstrative or probable reasonings”—as one of its parts or sub-faculties. Let us therefore call it the inclusive imagination. In the second sense that Hume distinguishes, “imagination” picks out the non-rational part or sub-faculty of the inclusive imagination—the part that is not reason. Hume indicates that this other, non-rational sub-faculty is responsible for our whimsies and prejudices (T 1.3.9.19n22; SBN 117n), and often suggests that its properties seem to be trivial (T 1.4.2.56, 1.4.6.6n50, 1.4.7.3, 1.4.7.6, 1.4.7.7; SBN 217, 254, 265, 267). Because it excludes reason as well as memory, let us call this non-rational sub-faculty the exclusive imagination.

b. Inclusive Imagination vs. Memory

Hume contrasts the inclusive imagination with the memory. What difference does he see between these faculties? Early in the Treatise, he explains that they differ in two main ways. First, the ideas that make up a memory are “much more lively and strong” than the ideas that we form by the inclusive imagination (T 1.1.3.1; SBN 9). Second, the ideas that make up a memory must occur in the same “order and form,” or “order and position,” as the impressions from which they are copied (T 1.1.3.2–3; SBN 9). For example, when I remember a melody that I have heard, my ideas of the notes composing that melody must occur in the same order as my earlier impressions of those notes. In contrast, the imagination “is not restrain’d to the same order or form with the original impressions” (T 1.1.3.2; SBN 9). I can imagine a melody made up of notes that I have experienced before, but occurring in an order that I have never experienced before.

According to Hume, then, the ideas that we form in the course of remembering things are not completely different from those that we form when we are imagining things. In fact, these ideas are intrinsically alike, save for their degree of force and vivacity: they are all “faint images” of impressions, or montages of such images; but the ideas of the inclusive imagination are even fainter than those of the memory.

c. Exclusive Imagination vs. Reason

Hume distinguishes two parts or sub-faculties within the inclusive imagination: the exclusive imagination and reason. What difference does he see between these sub-faculties? Again, there seem to be two main answers. First, these sub-faculties differ with respect to their function, or what they do. By “reason,” Hume here means the sub-faculty by which we make demonstrative and probable inferences. In contrast, the exclusive imagination is the sub-faculty by which we form non-rational whimsies and prejudices, and various imaginative “fictions,” which are discussed in section (5) below. Second, these sub-faculties differ with respect to the permanence, irresistibility and universality of their operations. Operations of reason, like inferring causes from their effects, are permanent, irresistible and universal features of human minds. In contrast, the whimsies and prejudices due to the exclusive imagination occur only at certain times and in certain places, and they can be avoided with sufficient strength of mind.

However, perhaps Hume thinks that some operations of the exclusive imagination are just as permanent, irresistible, and universal as those of reason. He says that probable reasoning and our belief that sensible objects continue to exist, at times when nobody perceives them, are “equally natural and necessary in the human mind” (T 1.4.7.4; SBN 266). But he also says that our belief in the continued, unperceived existence of sensible objects is a fiction due to the exclusive imagination (T 1.4.2.14–43 and 52; SBN 193–209 and 215). So, he seems to hold that at least one operation of the exclusive imagination—its production of this belief—is just as permanent, irresistible, and universal as the operations of reason.

According to some scholars, Hume uses the word “reason” in different ways, only sometimes using it to pick out the sub-faculty of the inclusive imagination by which we carry out demonstrative and probable reasoning. Therefore, the reader should be careful not to assume that Hume is always talking about this sub-faculty, whenever he talks about reason.

For further discussion of Hume’s contrast (or contrasts) between reason and the imagination, see section (7), below.

d. Continuities between Hume’s Views and His Predecessors’

Among Early Modern philosophers, the imagination was generally conceived as our faculty for forming a distinctive kind of idea: mental “images” that resemble sensory experiences. For example, René Descartes writes that “whatever we conceive with an image is an idea of the imagination” (“To Mersenne, July 1641”; CSMK 186) and explains that imaginative images resemble sensory experience:

When I imagine a triangle, for example, I do not merely understand that it is a figure bounded by three lines, but at the same time I also see the three lines with my mind’s eye as if they were present before me; and this is what I call imagining. (CSM 2:50)

When one imagines a triangle, it is “as if” one were sensing it. Similarly, Thomas Hobbes, Nicolas Malebranche and George Berkeley all characterize the imagination as a faculty for forming ideas that closely resemble sensory experiences.

As we have seen, Hume thinks that every idea is either simple or complex; that every simple idea is copied from a simple impression (that is, from a simple sensation, passion or emotion); and that every complex idea is made up entirely of simple ones. He must therefore accept that all ideas resemble experiences: a simple idea resembles the experience that we have, when we have the simple impression from which it is copied; and a complex idea resembles the experiences that we have, when we have the simple impressions from which its parts are copied. So, much like his predecessors, he holds that all the ideas we form by means of the inclusive imagination resemble sensory experiences—if the word “sensory” is construed in a broad way, so as to include passionate and emotional experiences. (Hume does not think that this is distinctive of the inclusive imagination: in his view, the memory also uses ideas that resemble sensory experiences. However, most of his Early Modern predecessors regarded memory as a kind of imagination, so there is no significant disagreement between him and them on this point.)

Hume’s Early Modern predecessors also thought that the imagination is a faculty by which we make a distinctive kind of transition among ideas: habituated, or associative, transitions. For example, Hobbes thinks that the successions of mental images that take place in the imagination tend to resemble the successions of sensory experiences that gave rise to those mental images. Similarly, Malebranche holds that each type of mental image is paired with a type of physical image or “trace” in the brain, and that these physical traces come to be connected or associated with each other; thanks to these connections among physical traces, the mental images that are paired with them also come to be associated. And Gottfried Leibniz writes that, in both human and non-human animal minds, the perceptions of the memory or imagination come to be associated by a kind of habituation.

Hume agrees with these philosophers that the inclusive imagination serves to associate its ideas, or faint images, with other perceptions; this applies to both of its parts or sub-faculties—reason and the exclusive imagination. Below, section (3c) discusses Hume’s views of imaginative association in detail; section (4) discusses some of its applications.

e. Discontinuities between Hume’s Views and His Predecessors’

There are two main discontinuities between Hume’s views of the imagination and those of earlier modern philosophers. First, numerous Early Modern philosophers held that we have a faculty of pure understanding or pure intellect, by which we can form purely intellectual ideas—ideas that are completely unlike sensations, passions, or emotions. For example, Descartes claims that we can understand the difference between a chiliagon (a 1,000-sided shape) and a myriagon (a 10,000-sided shape), but that we cannot represent this difference to ourselves by forming mental images. This is because the image that we form in trying to imagine a chiliagon is no different from the one that we form in trying to imagine a myriagon: in each case, the best that we can do is to make a fuzzy attempt to depict many sides (CSM 2:50). More importantly, by Descartes’s lights, we can form ideas of incorporeal things, such as God and the human soul, but we cannot imagine such things, because imagining is “simply contemplating the shape or image of a corporeal thing” (CSM 2:19). Descartes infers that, when we grasp the difference between a chiliagon and a myriagon, or conceive of God, we do so by forming a purely intellectual idea. Antoine Arnauld, Malebranche, Benedict De Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz also posit purely intellectual ideas, in order to explain certain kinds of human thought.

Hume does not include a faculty of pure intellect in his taxonomy of mental faculties: he thinks that all ideas are faint images, or montages of such images, belonging to the memory or to the inclusive imagination. He has at least three reasons for denying that we have a faculty of pure intellect. First, he argues that the Copy Principle rules out purely intellectual ideas (T 1.3.1.7; SBN 72–73). Copying involves resemblance: a copy resembles the original from which it is made. So, if every simple idea is an exact copy of a simple impression, and every complex idea is composed wholly of simple ideas, then every idea resembles an impression or several impressions. So, no idea is purely intellectual.

Second, Hume gives specific arguments against the existence of certain purely intellectual ideas that Descartes and his followers had posited. For example, Descartes argued that we conceive the nature of a particular material substance, like a piece of wax, by means of the pure intellect. In contrast, Hume argues that we can only conceive a substance to be a collection of sensible qualities “united by the imagination” (T 1.1.6.1–2; SBN 15–16). So, we conceive of substances by means of the imagination, not by means of a purely intellectual idea. Similarly, Descartes held that the idea of God is purely intellectual. In contrast, Hume argues that one can form an idea of God by augmenting one’s idea of one’s own mind with further ideas copied from impressions (E 2.6; SBN 19).

Third, Hume thinks that his opponents’ principal reason for positing a faculty of pure intellect is to “explain our abstract ideas, and to show how we can form an idea of a triangle, for instance, which shall neither be an isosceles nor a scalenum, nor be confin’d to any particular length or proportion of sides” (T 1.3.1.7; SBN 72). Hume thinks that he can explain our abstract ideas just by appealing to the ideas and basic functions of the inclusive imagination. If this explanation succeeds, then it shows that we do not need a faculty of pure intellect in order to form abstract ideas. Therefore, Hume thinks that his explanation undermines his opponents’ principal reason for positing this faculty. Section (4a), below, discusses Hume’s account of abstract ideas in more detail.

The second main discontinuity between Hume’s views and those of his predecessors concerns reasoning. According to many of Hume’s predecessors, including Descartes, Leibniz and John Locke, reasoning involves mental events or processes that are both rational and basic, meaning that they cannot be explained in terms of any simpler mental events or processes. In contrast, Hume tries to explain reasoning in terms of more basic mental functions, which are common to reason and to the exclusive imagination. For example, he thinks that the same basic principles of association among ideas explain both flights of fancy due to the exclusive imagination and probable inferences due to reason. This is why Hume regards reason and the exclusive imagination as two sub-faculties of the inclusive imagination: their functions are built up out of the same basic imaginative functions.

Because Hume places our whole faculty of reason within the inclusive imagination, it seems he must say that demonstrative reasoning can be explained in terms of functions that are common to reason and the exclusive imagination. But it is a hard question whether he can carry out this explanation successfully. For a helpful discussion of this issue, see Owen (1999, 92 and 96–98).

3. Five Basic Functions of the Inclusive Imagination

As a scientist of man, Hume aims to explain some mental functions in terms of others. More specifically, he aims to take a complex and initially puzzling mental function, like our ability to carry out sophisticated pieces of probable reasoning, and show how this function is built up out of several simpler and less puzzling functions. Of course, Hume does not go on forever in this process of breaking down complex mental functions into simpler ones. His science of man leaves some mental functions unexplained. These functions are the basic building blocks from which other, more complex, mental functions are built. This section presents five of the main basic functions that Hume attributes to the inclusive imagination—that is, functions that his science of man does not try to explain. The next two sections show how he uses these basic functions to explain several other, more complex mental and social phenomena—some due to reason, others to the exclusive imagination.

Two caveats here: First, saying that a function of the inclusive imagination is basic does not mean that it has no explanation at all, in Hume’s view. He suggests that events taking place in our brains might explain the inclusive imagination’s basic functions (T 1.2.5.20; SBN 60–61). But he does not insist that this is true, and he remains officially agnostic about what, if anything, explains these functions; this question falls outside the scope of his science of man. Second, saying that a mental function is basic does not mean that we have no evidence that it takes place. Hume seems to think that each of us can observe the basic imaginative functions taking place in our minds. So, we have observational evidence that they take place, even though we do not have a scientific explanation of how or why they do. He may also think that his success in using these basic functions to explain other, more complex phenomena gives him further evidence that they take place in our minds (Owen 1999, 77–79).

a. Forming Faint Copies of Simple Impressions

Hume thinks that each of our ideas is either copied from a simple impression (per the Copy Principle), or is built up entirely from simple ideas that are so copied. If our minds could not reproduce our simple impressions, by forming simple ideas copied from them, then we could not form any ideas at all. So, the function of reproducing simple impressions by forming copies of them must be common to the inclusive imagination and the memory—our two faculties for forming ideas. Of course, the copies or simple ideas that we form by means of the inclusive imagination have a lower degree of force, liveliness, or strength than those that we form by means of the memory. Hume does not try to explain how the inclusive imagination forms faint copies of our simple impressions; he simply observes that it does. Hence, this is a basic function of the inclusive imagination. Hume’s main discussions of this function are in Treatise Book 1, Part 1, Section 1; and in the first Enquiry, Section 2.

b. Manipulating the Parts of Ideas

Once we have acquired some ideas by forming copies of our impressions, the inclusive imagination can manipulate their parts in various ways. Hume gives several overlapping lists of these ways: for examples, see the Appendix to the Treatise, paragraph 2; the “Abstract” of the Treatise, paragraph 35; and the first Enquiry, Section 2, paragraph 5. Perhaps the most important two are i) what Hume calls separating or dividing ideas, and ii) what he calls uniting, compounding, or composing them. The inclusive imagination can break any complex idea into parts. For example, it can take an idea of a goat and break it down into an idea of the goat’s head, an idea of its torso, ideas of its legs, and so forth. This is what Hume calls separating or dividing ideas. Once it has broken some ideas down into their parts, it can reassemble these parts at pleasure. For example, it can combine the idea of a goat’s head with the idea of a lion’s body, so as to form the idea of a chimera. This is what Hume calls uniting, compounding, or composing ideas.

These two functions of the inclusive imagination are captured by Hume’s Liberty Principle, which says that the imagination is free to “transpose and change its ideas” by separating and re-uniting their parts (T 1.1.3.4; SBN 10). The Liberty Principle plays an important role in Hume’s philosophy by supporting his Separability Principle, which says that “whatever objects are different are distinguishable, and . . . whatever objects are distinguishable are separable by the thought and imagination” (T 1.1.7.3; SBN 18); by “objects,” here, Hume seems to mean the objects of thought or imagination—that is, the things of which we think or which we imagine. (For a helpful discussion of Hume’s varied use of the word “object,” see Grene 1994.) In turn, the Separability Principle underwrites some of Hume’s central arguments—for example, his argument that the proposition “whatever begins to exist, must have a cause of existence” is “neither intuitively nor demonstratively certain” (T 1.3.3.1–3; SBN 78–80).

A third important way of manipulating the parts of our ideas is what Hume calls augmenting our ideas: in other words, replicating a part of an idea and adding the replica back to the original idea, so as to produce an idea of something larger than what the original idea represented. Hume thinks that this allows us to form an idea of God, using only ideas that are copied from impressions (E 2.6; SBN 19).

Hume does not explain how the inclusive imagination manipulates the parts of its ideas in these ways. Doing so is another of its basic functions.

c. Association

Hume thinks that the inclusive imagination naturally associates some perceptions with others. He usually speaks of the association of ideas, but in some of the most important cases that he discusses, an idea is associated with an impression. For example, he claims that probable reasoning involves “a relation or association in the fancy betwixt the impression and idea” (T 1.3.8.7; SBN 101). Hume’s main discussions of association are in Treatise Book 1, Part 1, Section 4, and in the first Enquiry, Section 3.

According to Hume, there are three principles of association among ideas—in other words, there are three basic laws of the inclusive imagination, describing the ways in which ideas become associated with each other or with impressions. First, ideas tend to become associated if the objects that they represent resemble each other. In Hume’s example, an idea of a picture is associated with an idea of the object(s) that this picture depicts (E 3.3; SBN 24). Second, ideas tend to become associated if the objects that they represent are contiguous to each other, meaning that they are near to each other in space or time. In Hume’s example, the idea of an apartment in a building is associated with ideas of the other apartments in that building (ibid.). Third, ideas tend to become associated if the objects that they represent are causally related. In Hume’s example, the idea of a wound is associated with an idea of the pain caused by that wound (ibid.). Really, then, the phrase “association of ideas” covers three functions of the inclusive imagination.

Hume stresses that these three functions of the inclusive imagination are basic, or left unexplained by his science of man, while also stressing that we have evidence that the inclusive imagination performs these functions:

These are therefore the principles of union or cohesion among our simple ideas . . . Here is a kind of ATTRACTION, which in the mental world will be found to have as extraordinary effects as in the natural, and to show itself in as many and as various forms. Its effects are every where conspicuous; but as to its causes, they are mostly unknown, and must be resolv’d into original qualities of human nature, which I pretend not to explain. Nothing is more requisite for a true philosopher, than to restrain the intemperate desire of searching into causes, and having establish’d any doctrine upon a sufficient number of experiments, rest contented with that, when he sees a farther examination wou’d lead him into obscure and uncertain speculations. (T 1.1.4.6; 12–13. See also T 1.1.7.15; SBN 24)

Hume uses these three basic functions of the inclusive imagination to explain numerous other, more complex mental functions—some due to reason, others to the exclusive imagination. Sections (4) and (5), below, discuss some important examples. Hume is especially proud of this aspect of his science of man. He writes that his “use . . . of the principle of the association of ideas” is what, “if any thing,” can entitle him to “so glorious a name as that of an inventor” (T Abs 35; SBN 661).

In his discussions of the passions, Hume expands his account of association in several ways. Most importantly, he adds that the association of two ideas is strengthened if they are accompanied by impressions that resemble each other. This is because resembling impressions are themselves associated, and the two associative relations—that of the ideas, and that of the accompanying impressions—combine to give the mind a “double impulse” to move, associatively, from the first idea-impression pair to the second (T 2.1.4.4; SBN 284). Hume calls this phenomenon the “double relation of ideas and impressions” (T 2.1.5.5; 286–7). He uses it to explain the passions of pride, humility, love, and hatred.

Hume also adds that, in its associative transitions, the inclusive imagination gravitates towards objects that are more important, or closer to oneself in space and time. An idea that represents a relatively unimportant object—for example, a servant—tends to produce ideas of relatively important objects that are associated with it—for example, the servant’s master; in contrast, an idea of a master does not tend to produce an idea of his servant. Similarly, an idea that represents a relatively distant object—for example, one of Jupiter’s moons—tends to produce ideas of relatively nearby objects that are associated with it—for example, an idea of the Earth’s moon; in contrast, an idea of the Earth’s moon does not tend to produce an idea of one of Jupiter’s moons. When two ideas are associated in such a way that each of them is equally likely to be accompanied or followed by the other, Hume says that there is a “perfect relation” between the objects that they represent (T 2.2.4.10; 355).

d. Transmitting Force and Liveliness among Associated Perceptions

Hume thinks that impressions have more force and liveliness (or vivacity) than ideas in the memory, which in turn have more force and liveliness than ideas in the imagination. But he does not think that the latter all have the same low degree of force and liveliness; some of them have a higher degree than others. This allows him to explain the difference between an idea of a contingent state of affairs that we believe to obtain and an idea of one that we merely entertain or think about. Consider two people: someone who believes that there will be a third world war, and someone who entertains the thought that there will be one, but does not believe it. Hume will say that each of these people forms an idea in her imagination. (If the idea is a product of probable reasoning, it belongs to reason and hence to the inclusive imagination; if it is a whimsy or flight of fancy, it belongs to the exclusive imagination.) He will also say that each of their ideas represents the same thing—namely, a third world war’s taking place in the future. But there is a difference between the two ideas, which Hume must explain: one of them is a belief; the other is not. His explanation is that the former idea has more force and liveliness than the other.

Hume defines a belief as “a lively idea related to or associated with a present impression” (T 1.3.7.5; SBN 96). This is because he thinks that an idea must inherit its force and liveliness, directly or indirectly, from an impression. The impression gives force and liveliness to the idea, and thereby turns that idea into a belief; this belief, in turn, can give force and liveliness to other ideas.

In order for one perception to give force and liveliness to another, these perceptions must be associated: associative relations are akin to “pipes or canals” through which force and liveliness can flow (T 1.3.10.7; SBN 122). Hume thinks that associative links due to causation transmit a higher degree of force and liveliness than those due to resemblance or contiguity (T 1.3.9.8; SBN 110).

Transmitting force and liveliness among associated perceptions—especially, among those associated due to causation—is a fourth basic function of the inclusive imagination. In the Treatise, Hume uses it, together with the principles of association of ideas, to explain several important mental phenomena, including probable reasoning and sympathy. Sections (4b) and (4c), below, discuss these phenomena.

Hume’s main discussions of the transmission of force and liveliness are in Treatise Book 1, Part 3, Sections 7–9. Shortly after writing these sections, Hume seems to have changed his view about the nature of belief. In an Appendix published in the following year, together with Treatise Book 3, he wrote that two ideas of the same object can differ in ways other than their degree of force and vivacity (T App 22; SBN 636), and that “reflection on general rules keeps us from augmenting our belief upon every encrease of the force and vivacity of our ideas” (T 1.3.10.12App; SBN 632). This suggests that he no longer identified belief with a higher-than-usual degree of force and vivacity. Later, in the first Enquiry, he refrained from explicitly likening beliefs to impressions, in respect of their force and vivacity (E 5.11–13; SBN 48–50). How significantly did he change his views? Commentators disagree: for two different perspectives, see Owen (1999, 172–4) and Wilbanks (1968, 29–30). Whatever the answer may be, Hume clearly continued to hold that an idea is “enlivened” or receives additional “force and vigour” (E 5.15; SBN 51) when it is associatively related to an impression.

e. Completing the Union of Related Objects

Hume claims that, when our ideas of two objects are associated by certain relations, we tend to imagine further relations among them, in order to “compleat the union” (T 1.4.2.55; SBN 217); his main discussions of this function are in Treatise Book 1, Part 4, Sections 2 and 5.

Hume claims that this basic function of the inclusive imagination explains why those who believe in external objects that cause their impressions tend to believe that these objects also resemble their impressions: they add the relation of resemblance to that of causation in order to complete the union between the external object and the impression (T 1.4.2.55; SBN 217). Similarly, this function explains why we believe that sounds, tastes, and smells have spatial locations. In Hume’s view, these sensible qualities “exist nowhere” (T 1.4.5.10; SBN 235–6)—they do not have spatial locations. But we typically experience the taste and smell of an olive, say, at the same time as experiencing the olive itself; and we take the olive to cause its taste and smell. Because of our tendency to complete the union of related objects, we imaginatively add the relation of spatial contiguity to those of temporal contiguity and causation. In other words, we imagine that the olive’s taste and smell are located where the olive is.

Most importantly, Hume uses this basic imaginative function to explain certain forms of projection—our mind’s tendency to “spread itself on external objects” (T 1.3.14.25; SBN 167). Projection plays an important role in his theories of causal necessity and moral value. Section (4d), below, discusses it.

4. Four Non-Basic Functions of the Inclusive Imagination

Much of Hume’s philosophical work aims to explain how the inclusive imagination’s basic functions work together with each other and with other features of our minds, such as our passions, to produce complex mental and social phenomena. This section focuses on four important examples: abstract ideas, probable reasoning, sympathy, and projection. The next section focuses on an important class of examples that fall under the heading of “fiction.”

a. Abstract Ideas

Hume says that every idea is individual or particular. By this, he means both that the idea itself is a particular (not a universal) and that it represents a particular object: when we form an idea, “the image in the mind is only that of a particular object” (T 1.1.7.6; SBN 20). However, we are not restricted to thinking of one particular thing at a time. We can grasp thoughts like all dogs are mammals and all triangles are shapes. If an idea represents just one particular object, then how can we do this—how can we think of all the particular dogs that exist, or all the particular triangles? Hume’s answer is that a “particular idea” comes to serve as an “abstract” or “general” representation; in other words, it comes to represent all the particular things of some sort. He explains how this happens by appealing to the association of ideas.

Hume proposes that an idea serves as a general representation, if it is called to mind by a word—a common noun like “dog” or “triangle”—which is associated with many ideas of resembling objects. Suppose that, on hearing the word “dog,” you happen to form an idea of a particular dog, Fido. If it occurred on its own, this idea would represent just this one particular dog. But when it occurs in partnership with a word that is also associated with many other ideas of particular dogs (Spot, Rover, and so forth), the idea of Fido serves as a proxy for those other ideas (T 1.1.7.7–10; SBN 20–22). Hence, it serves as a representation of all dogs.

This explanation involves two of Hume’s principles of association. First, it involves contiguity. We have often uttered the word “dog,” or (more probably, if we are learning a language) have often heard this word uttered, in the presence of Fido. This contiguity in space and time between the word “dog” and Fido leads us to associate that word with him. Second, it involves resemblance. Because Fido, Spot, Rover, and other dogs resemble each other in many important ways, we come to associate the same term with each of them. Also thanks to this resemblance, an idea of one of these dogs tends to be followed by one or more ideas of the other dogs. Hume thinks that this helps one idea to serve as a proxy for the others.

Hume thinks that the main reason why other philosophers have posited a faculty of pure intellect, distinct from the inclusive imagination, is to “explain our abstract ideas, and to show how we can form an idea of a triangle, for instance, which shall neither be an isosceles nor a scalenum, nor be confin’d to any particular length or proportion of sides” (T 1.3.1.7; SBN 72). He presumably thinks that his own account of abstract ideas undermines this reason: it shows that the inclusive imagination can explain our abstract ideas; so, there is no need to posit an additional faculty of pure intellect.

Hume’s main discussion of this non-basic function of the inclusive imagination is in Treatise Book 1, Part 1, Section 7.

b. Probable Reasoning

By “probable reasoning,” “moral reasoning,” or “reasoning concerning matter of fact,” Hume means reasoning to beliefs about matters of fact that we have not observed. For example, we all believe that the sun will rise tomorrow. But this belief is not due to observation: we cannot have observed the sun’s rising tomorrow, because it has not happened yet. So, our belief that the sun will rise tomorrow must be due to probable reasoning: we must have reasoned our way to this belief, based on other things that we have observed. Hume distinguishes two main kinds of probable reasoning, which he calls proofs and probabilities (T 1.3.11.2; SBN 124). A proof is a piece of probable reasoning whose conclusion is “entirely free from doubt and uncertainty” (T 1.3.11.2; SBN 124). For example, we have no doubt that the sun will rise tomorrow. So, the piece of probable reasoning that leads us to this conclusion is a proof. A probability is a piece of probable reasoning whose conclusion is “still attended with uncertainty” (T 1.3.11.2; SBN 124). For example, when I have a headache, I believe with some confidence that taking acetaminophen will cure it. But I do not believe this with complete certainty: taking acetaminophen usually cures my headaches, but not always. So, the piece of probable reasoning that leads me to conclude that taking acetaminophen will cure my current headache is a probability. (To avoid confusion, it is important to recognize that Hume uses the terms “probable reasoning” and “probability” in two senses: i) an inclusive sense, in which these terms denote the genus of reasoning whose species are proofs and probabilities; and ii) an exclusive sense, in which they denote just one species of this genus—probabilities as opposed to proofs. For examples of the inclusive sense, see T 1.3.6.4, 1.3.6.6–7 and 1.3.9.19n22; SBN 89, 89–90 and 117–18n; for examples of the exclusive sense, see T 1.3.11.2; SBN 124. In this section, I will use “probable reasoning” only in the inclusive sense, and “probability” only in the exclusive sense.)

Hume observes that our ordinary actions and our scientific inquiries—including those that he himself conducts, as a scientist of man—depend on probable reasoning and the beliefs that it produces. Therefore, it is especially important to him to explain how our minds carry out this kind of reasoning. He argues that probable reasoning is a non-basic function of the inclusive imagination, built up from two basic ones: association, and the transmission of force and vivacity among associated perceptions.

To see this, let us consider Hume’s favorite example of an elementary proof: we see one billiard ball hurtling across the table towards a second ball, which is unobstructed; and we form the belief—without any doubt or uncertainty—that the two balls will collide, and that the second ball will start to move. In order to explain this piece of reasoning, Hume breaks it down into three parts (T 1.3.5.1; SBN 84). The first part is our “original impression”—in this case, a sensory impression of the two billiard balls. In general, Hume avoids the question of how our sensory impressions are produced, so he leaves this part of our reasoning unexplained.

The second part of our probable reasoning is a mental “transition” from our original impression to an idea that represents the two balls colliding, and the second ball starting to move. Hume famously argues that this transition is due to imaginative association. In the past, whenever we have observed billiard balls in similar situations—one ball hurtling towards another, unobstructed, ball—we have observed the balls to collide, and the second start to move. This course of past experience has established an associative relation: a perception of billiard balls in this situation now calls to our mind an idea of the balls colliding, and the second starting to move. It is due to this associative relation, Hume claims, that the sight of billiard balls in this situation now causes us to form such an idea (T 1.3.6.12–16; SBN 92–94). This is an example of association by causation—one of the three principles of association that Hume identifies; see section (3c), above. Hume thinks that only causation can inform us about unobserved matters of fact: that is, we can only learn about an unobserved matter of fact if it is causally related to some other matter, or matters, of fact that we have observed (T 1.3.2.2–3; SBN 73–74, E 4.4–5; SBN 26–27). So, he thinks that all probable reasoning involves association by causation.

The third part of our probable reasoning is the transmission of force and liveliness to our idea, so that we believe—not just entertain the thought—that the billiard balls will collide and that the second one will start to move. Once he has established that imaginative association explains our transition from our impression of the billiard balls to this idea, this third part of our reasoning is easy for Hume to explain. Impressions have a high degree of force and liveliness, and transmitting force and liveliness among associated perceptions is a basic function of the inclusive imagination. So, we should expect the transmission of force and liveliness from our impression to our idea of the two billiard balls colliding, and the second one’s starting to move. As a result, our idea becomes a belief.

Hume writes that probabilities are “deriv’d from the same origin”—that is, from the same basic functions of the inclusive imagination—as proofs (T 1.3.11.1; SBN 124). In the Treatise, he distinguishes three kinds of probability: the probability of chances; the probability of causes; and probability arising from analogy (T 1.3.11.3, 1.3.12.25; SBN 124–5, 142). We rely on the probability of chances and the probability of causes when we do not have a large, uniform body of past experience concerning the matters of fact about which we are reasoning. For example, when I roll a fair, six-sided die, I do not have a uniform body of past experience concerning which face will land uppermost: in my past experience, rolling the die has sometimes been followed by one face landing uppermost, sometimes by another face landing uppermost. But if the die has four faces marked with squares, and only two marked with circles, I come to believe with some confidence that one of the faces marked with a square will land uppermost; this belief derives from the probability of chances. Similarly, when I take acetaminophen in the hopes of curing my headache, I do not have a uniform body of past experience concerning the curing of my headache: in my past experience, taking acetaminophen has usually been followed by the curing of a headache—but not always. Again, I come to believe with some confidence that taking acetaminophen on this occasion will be followed by the curing of my headache; this belief derives from the probability of causes. Hume argues that, like proofs, both the probability of chances and that of causes are explained by the association of ideas and the transmission of force and vivacity between associated perceptions.

We rely on probability arising from analogy when we observe a matter of fact that bears some resemblance, but not a perfect resemblance, to matters of fact that we have previously observed. Suppose that I have a large body of past experience of Labradors in which, whenever a Labrador has approached me with its tail wagging, it has then greeted me effusively; suppose, also, that I have no past experience of German Shepherds, but that I now see one approaching me with its tail wagging. Because this German Shepherd does not perfectly resemble anything that I have previously experienced, I do not have a proof that it will greet me effusively. But, because it bears some resemblance to the Labradors that I have experienced, I believe with some confidence that it will greet me effusively. According to Hume, this belief is due to probability arising from analogy—in this case, the analogy between the German Shepherd that I now experience and the Labradors that I have previously experienced. Hume holds that this species of probability is explained by the same basic functions of the inclusive imagination as proofs, the probability of chances, and the probability of causes (T 1.3.12.25; SBN 142). In the first Enquiry, Hume does not class analogy as a third species of probability; instead, he writes that all probable reasoning—including proofs, as well as probabilities—is “founded on a species of Analogy” (E 9.1; SBN 104).

When we carry out simple pieces of probable reasoning, we do so reflexively. For example, when we see one billiard ball hurtling towards another, we immediately form the belief that the balls will collide, and that the second will start to move; we need not reflect on our past experiences, or construct an argument, in order to do so. Not all probable reasoning is like this. More sophisticated pieces of probable reasoning are reflective, not reflexive: they involve reflection on past experience, and the construction of arguments. (For the “reflexive/reflective” distinction, see Owen 1999, 149–50.) But Hume explains this reflective kind of probable reasoning in terms of the reflexive kind. In order to carry out reflective probable reasoning, we need to establish general principles to serve as premises in our arguments, such as “the principle, that like objects, plac’d in like circumstances, will always produce like effects” (T 1.3.8.14; SBN 105; see also T 1.3.12.7–12; SBN 133–5). And we cannot begin to establish such principles, except by means of reflexive probable reasoning. For example, we reflexively believe that like objects in like circumstances will produce like effects because “we have many millions [of experiments] to convince us of this principle,” and so “this principle has establish’d itself by a sufficient custom” (ibid.).

So, Hume explains sophisticated, reflective probable reasoning by showing how it is built up from unsophisticated, reflexive probable reasoning; and, as we have seen, he explains unsophisticated, reflexive probable reasoning in terms of two basic functions of the inclusive imagination: association and the transmission of force and liveliness. In Hume’s view, then, we can conduct sophisticated research in the empirical sciences only thanks to the inclusive imagination and its basic functions.

Hume’s main discussions of proofs are Treatise Book I, Part 3, Sections 4–7; the “Abstract” of the Treatise, paragraphs 8–23; and the first Enquiry, Sections 4 and 5. His main discussions of probabilities are Treatise Book 1, Part 3, Sections 11–13; and the first Enquiry, Section 6.

c. Sympathy

In Hume’s view, to “sympathize” is to share the feelings of a person whom one encounters. At the sight of a cheerful face, one tends to feel more cheerful oneself. Similarly, at the sight of an angry or sorrowful face, one’s own mood is dampened. In each case, a sentiment or feeling of the person observed is communicated, by sympathy, to the observer.

Hume’s account of sympathy resembles that of probable reasoning in two ways. First, he explains sympathy in terms of the same two basic imaginative functions: association and the transmission of force and vivacity among associated perceptions. Second, as with probable reasoning, Hume distinguishes reflexive and reflective forms of sympathy.

Consider an example of the reflexive form of sympathy: you meet a joyful person, and consequently feel the passion of joy yourself. Hume distinguishes two components within this process. First, a piece of probable reasoning: you observe the effects of joy in the other person’s voice and gestures; from your observation of these effects, you infer the presence of joy in her mind (T 2.1.11.3, 3.3.1.7; SBN 317, 575–6). This first component explains why you should come to believe in the presence of joy in the other person’s mind. But it does not yet explain why you should come to feel the passion of joy yourself. This explanation comes from the second component that Hume discerns in the process of sympathizing. He claims that you always have a very forceful and vivacious perception of yourself (T 2.1.11.4; SBN 317). Since you are both human beings, the joyful person whom you have met resembles you closely, and—in the case we are now considering—she and the joy that she feels are contiguous to you in space and time. Thanks to these relations of resemblance and contiguity, your very forceful and lively perception of yourself is associated with your idea of this other person and the joy that she feels. Thanks to the inclusive imagination’s basic function of transmitting force and vivacity among associated perceptions, your idea of the other person’s joy receives an extra dose of force and vivacity from your perception of yourself. Your idea of the other person’s joy therefore becomes an impression of joy—that is, it becomes an actual instance of the passion of joy (T 2.1.11.5–7; SBN 319). In Hume’s view, this is the process by which we come to sympathetically share the passions or feelings of other people. As we can see, it involves the same two basic imaginative functions twice over: association and the transmission of force and vivacity among associated perceptions explain both the initial piece of probable reasoning that produces an idea of the other person’s passion, and the extra dose of force and vivacity that this idea receives, which turns it into a passion.

Hume argues that our moral sentiments—the approval that we feel when considering someone’s virtues, and the disapproval when considering her vices—derive from sympathy (T 3.3.1.6–26; SBN 575–89). When we consider somebody with a character-trait that is useful to those around her—generosity, for example—we sympathetically share the pleasurable passions of joy and gratitude that this character-trait induces in the people who benefit from it. Because we share these pleasurable passions, we morally approve of the character-trait that causes them.

If all our sympathetic responses were reflexive, however, then our sentiments of moral approval and disapproval would fluctuate wildly. As people become more distant from us in space and time, our ideas of them and their passions become less strongly associated with our forceful and vivacious perceptions of ourselves; we therefore sympathize less strongly with them. So, if all of our moral sentiments derived from reflexive sympathy, we would not approve as much of past virtues as we do of present ones, and we would not approve as much of the virtues of spatially distant people as we do of the virtues of people living close to us. However, our moral sentiments do not in fact fluctuate in these ways: “we give the same approbation to the same moral qualities in China as in England” (T 3.3.1.14; SBN 581). Hume explains that this is because our moral sentiments derive from a more sophisticated form of sympathy, in which we “correct” our sentiments by a kind of “reflection” (T 3.3.1.17; SBN 583). When we sympathize in this reflective way, we consider only the ways in which a person’s character tends to affect the people with whom she interacts—“those, who have any commerce with the person we consider” (T 3.3.1.18; SBN 583). We base our moral sentiments not on how reflexive sympathy makes us feel, but on how reflective sympathy tells us that we would feel, if we were to encounter the person whose character we are evaluating, and the people whom she directly affects.

Hume holds that the reflective kind of sympathy from which our moral sentiments derive is a corrected form of reflexive sympathy; and, as we have seen, he explains reflexive sympathy in terms of two basic functions of the inclusive imagination—association and the transmission of force and liveliness. In Hume’s view at the time of writing the Treatise, then, we owe our moral sentiments, like our capacities for abstract thought and probable reasoning, to the imagination and its basic functions.

Hume’s main discussions of sympathy are in Treatise Book 2, Part 1, Section 11; and Book 3, Part 3, Section 1. In his Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (hereafter, second Enquiry), Hume does not discuss sympathy as extensively, or in as much detail, as he does in the earlier Treatise. This leads some commentators to think that he changed his views about the origins of our moral sentiments, in between writing these works. Abramson (2001) argues convincingly that this is not the case, and that the imaginative mechanism of reflective sympathy plays much the same role in the second Enquiry as it does in the Treatise.

d. Projection

In Hume’s view, when we think that one thing causes another, we take there to be a “necessary connexion” between the cause and its effect. Given that the cause happens, we take it that the effect must follow. For example, given that a speeding billiard ball collides with an unobstructed, stationary ball, the latter must start moving; or, given that a burning match is applied to dry kindling in an oxygen-rich environment, the kindling must start burning. Hume investigates at length how we acquire the idea of this necessary connection between cause and effect, and what this idea really represents. He argues that this idea does not represent anything that belongs to, or exists between, the cause and effect themselves. Instead, it represents a feature of our minds: “an internal impression of the mind, or a determination to carry our thoughts from one object to another” (T 1.3.14.20; SBN 165). The “determination” of which Hume writes here is the transition involved in reflexive probable reasoning. By calling this transition an impression, Hume suggests that it has a distinctive feeling—when we see one billiard ball strike another, we feel ourselves determined to believe that the second ball will start moving. When we think or speak of two events as if they were necessarily connected—for example, when we say that a billiard ball must start moving, given that another ball has struck it—we are “spreading” this feeling of determination, which exists in our own mind, onto the events themselves:

’Tis a common observation, that the mind has a great propensity to spread itself on external objects, and to conjoin with them any internal impressions, which they occasion, and which always make their appearance at the same time that these objects discover themselves to the senses. Thus . . . we suppose necessity and power to lie in the objects we consider, not in our mind, that considers them; notwithstanding it is not possible for us to form the most distant idea of that quality, when it is not taken for the determination of the mind, to pass from the idea of an object to that of its usual attendant. (T 1.3.14.25; SBN 167)

Scholars often express this claim in terms of projection: in Hume’s view, they say, we project our psychological determination to expect one event, given that another has taken place, onto the causally related events themselves. Hence, some scholars say that Hume holds a projectivist view of causal necessity (for example, see Beebee 2006).

Hume indicates that two basic functions of the inclusive imagination explain why we project our impression, or determination, onto the causally related events themselves. The first is association. Our impression or determination occurs at around the same time as the causally related events (in Hume’s language, it is contiguous to them in time), and it is caused by the first of these events—we are determined to expect motion in the second billiard ball because we see the first ball hurtling towards it. Because of this contiguity and this causal relation, the causally related events come to be associated with our impression or determination. The second basic function involved in projection is our propensity to complete the union of related objects: because the causally related events are temporally contiguous with, and cause, our impression or determination, our imagination tends to “feign” a relation of spatial contiguity between them as well (T 1.4.5.12; SBN 237–8). In other words, we complete the union between the causally related objects, on the one hand, and our internal impression or determination, on the other, by imagining that the internal impression occurs outside our mind, in the very place where the causally related events are located. That is to say, we project that internal impression onto those events.

Hume makes similar-sounding appeals to projection elsewhere in his philosophical works. For example, he writes that “taste”—the faculty which gives us our sentiments of aesthetic beauty and deformity, and of moral vice and virtue—“has a productive faculty, and gilding or staining all natural objects with the colours, borrowed from internal sentiment, raises in a manner a new creation” (second Enquiry, Appendix 1, paragraph 21). This leads some commentators to say that our aesthetic and moral evaluations involve projection, in Hume’s view: when we think of something as beautiful, or of someone as morally vicious, we are projecting our internal sentiments onto them. Hume does not explain how these aesthetic and moral kinds of projection occur. But, as he aims to explain human mental phenomena systematically, by appeal to a small number of basic principles, he is likely to explain them by means of the basic imaginative functions that he uses to explain why we project our internal impression of causal necessity.

Even among those scholars who agree that Hume gives projectivist theories of causation, morality, and aesthetics, there are disagreements about exactly what he understands projection to be, and what his projectivism implies. For example, some scholars think that projection is a kind of error that we make, while others think that projection need not involve any kind of error. For a second example, some scholars think that Hume’s projectivist theories of causal necessity and moral value are, in some sense, anti-realist—in other words, these theories imply that causal necessity and moral value are, in some sense, not real features of the world—while others think that his projectivism is consistent with a realist view of the projected features. For a helpful discussion of projection in general, and of Hume’s use of projection in particular, see Kail (2007).

The main texts that have inspired projectivist interpretations of Hume are Treatise Book 1, Part 3, Section 14, especially paragraphs 20–29; and Appendix 1 of the second Enquiry.

5. Fictions of the Imagination

a. Fictions in Hume’s Science of Man

Hume’s science of man aims to explain the most general beliefs and ways of thinking that we adopt in the course of ordinary life and in philosophical reflection. Often, Hume concludes that these beliefs and ways of thinking are not products of demonstrative or probable reasoning but, instead, are fictions produced by the exclusive imagination. According to him, the fictions that we form in ordinary (or “vulgar”) life include our belief in aggregates that have “unity” or oneness, such as one crowd, an aggregate of people; our belief that certain objects persist through time without changing; and our belief, of sensible objects like coffee cups, table, and chairs, that they continue to exist at times when nobody perceives them. Hume thinks that, in the course of philosophical reflection, we tend to form further fictions. For example, when we reflect philosophically on our sensory experiences, we come to believe that the only objects truly “present to” our minds are impressions and ideas, but that some of our impressions are caused by and represent external, material objects; Hume regards belief in these external, represented objects as a new fiction. As well as calling these beliefs fictions, Hume calls the distinctive imaginative process or operation that produces them fiction (for example, see T 1.2.3.11 and 1.4.2.29; SBN 37 and 200–201). This double use of the term “fiction” is in keeping with ordinary eighteenth century English usage. Johnson’s 1755–6 Dictionary of the English Language shows that, in eighteenth century English, the term “fiction” could mean both “the thing feigned or invented” (hence, Hume applies the term to certain ideas and beliefs) and “the act of feigning or inventing” (hence, Hume applies the term to the imaginative processes responsible for those ideas and beliefs).

Evidently, Hume thinks that many of our beliefs are fictions of the imagination. Fictions are so important within his science of man, one commentator suggests, that “what is commonly called Hume’s theory of impressions and ideas ought to be called the theory of impressions, ideas, and fictions” (Traiger 1987, 381). But it is hard to interpret Hume’s views about fictions. He suggests that fictions involve “apply[ing]” an idea to an object or impression from which we cannot derive that idea, and that this is an “improper” and “inexact” way of using that idea (T 1.2.3.11; SBN 37). But it is not clear what this means: in what sense do fictions involve an improper and inexact use of our ideas? Different commentators answer this question in different ways. According to some, Hume sees all fictions as falsehoods. According to others, he allows that some fictions may be true, but thinks that we lack evidence or justification for believing them. According to others still, he sees fictions as incoherent or unintelligible; if this is correct, then fictions may not be genuine ideas or beliefs, but pseudo-ideas or -beliefs, in Hume’s view. Of course, it is possible to combine these interpretations by distinguishing different kinds of fictions: for example, we may interpret Hume as thinking that some fictions are falsehoods, while others are unintelligible.

The rest of this section briefly examines three of the most important fictions that Hume discusses. It aims to exhibit the features of his discussions that motivate each type of interpretation that we have just surveyed. Hume’s discussions of these fictions are in Treatise Book 1, Part 4, Sections 2 and 3.

b. The “Vulgar” Fiction of a Continued Existence

In the Treatise section “Of scepticism with regard to the senses,” Hume tries to explain how we come to believe in bodies, or material objects, that continue to exist at times when nobody perceives them. He thinks that this belief can take two different forms: a “vulgar” or ordinary form, and a “philosophical” form. Hume thinks that the only things “present to the mind” are perceptions, or impressions and ideas (T 1.2.6.8, T Abs 5; SBN 67, 647). But ordinarily, he thinks, we do not realize this. Instead, we take certain of our sense-impressions to be bodies—that is, we ordinarily believe, of certain sense-impressions, that they continue to exist at times when they are not present to our minds (T 1.4.2.31, 1.4.2.36; SBN 202, 205). Hume calls this “vulgar” belief “the fiction of a continu’d existence” (T 1.4.2.36; SBN 205).

According to Hume, the main reason why we entertain this “vulgar” fiction is the “constancy” of certain sense-impressions before and after an interruption in our experiences (T 1.4.2.23; SBN 198–9). Suppose that I shut my eyes for a moment and that, upon re-opening them, I receive sense-impressions of the furniture in the room that closely resemble those that I received before shutting my eyes. Because of this resemblance or “constancy,” when I recall the earlier impressions, I naturally recall the later impressions, too: my mind “readily passes from one to the other,” due to the association of ideas of resembling objects. Thanks to a complicated imaginative mechanism, which Hume describes over several pages, this association of ideas leads me to imaginatively fill the gap in the sequence of sense-impressions that I received: I imaginatively construct ideas of furniture existing during the time when my eyes were shut, connecting up my memories of the last furniture-impression that I received before shutting my eyes and the first one that I received after re-opening them (T 1.4.2.31–40; SBN 201–8). Because these imaginatively constructed ideas are associated with memories, a high degree of force and vivacity is transmitted to them (T 1.4.2.41–42; SBN 208–9). Thanks to this mechanism, which involves both the association of ideas and the transmission of force and vivacity among related perceptions, I ordinarily come to believe, of my furniture-impressions, that they continued to exist while my eyes were shut.

However, Hume argues that none of our sense-impressions continue to exist at times when they are not present to our minds (T 1.4.2.44–45; SBN 210–11). When I shut my eyes, the furniture-impressions that were present to my mind cease to exist; when I re-open my eyes, new furniture-impressions are created in my mind, which are similar, but not numerically identical, to the earlier ones. So, the “vulgar” fiction of a continued existence is false, according to Hume. This is consistent with an interpretation on which Hume thinks that all fictions are falsehoods; however, it is also consistent with one on which Hume thinks that only some fictions are falsehoods, while others are unjustified beliefs or unintelligible pseudo-beliefs.

c. The Philosophical Fiction of Double Existence

Numerous Early Modern philosophers shared Hume’s view that only perceptions are ever “present to the mind,” but also held that we perceive bodies that continue to exist at times when nobody perceives them. These philosophers thought that we can perceive bodies by means of certain sense-impressions, because these impressions are caused by bodies, and represent those bodies to us. Hume calls this philosophical theory of how bodies are perceived the “opinion of a double existence of perceptions and objects” (T 1.4.2.46; SBN 211), because the theory posits two kinds of existent things: “perceptions,” or impressions that represent bodies to us; and “objects,” the bodies that are represented by (and in that sense are the “objects” of) our impressions.

Hume argues that this theory of double existence is “a new fiction,” due to the exclusive imagination, like the “vulgar” fiction that it replaces (T 1.4.2.52; SBN 215). However, he does not say that this new, philosophical fiction of double existence is false. Instead, he emphasizes that we cannot reason our way to believing it. We believe it only due to the exclusive imagination. This suggests that Hume regards the fiction of double existence as a belief that is unjustified, or inadequately supported by our evidence for it, but that may nonetheless be true.

d. The Philosophical Fiction of an Underlying Substance

Hume thinks that an ordinary sensible object, like a peach or melon, is just an aggregate of sensible qualities: for example, a ripe peach is an aggregate of a yellow-orange color, a fuzzy texture, solidity, and a sweet smell and taste (T 1.4.3.2, 1.4.3.5; SBN 219, 221). However, he thinks that we are prone to suppose otherwise. Instead of taking a peach to be an aggregate of many sensible qualities, we take it to be one thing. This leads to a kind of philosophical puzzlement: how can many things (the many aggregated qualities) also be one thing—isn’t this an “evident contradiction” (T 1.4.3.2; SBN 219)? According to Hume, many philosophers have responded to this puzzle by supposing that a peach is not the same thing as its sensible qualities, but is instead “an unknown something”—a substance or substratum that underlies its sensible qualities, and in which those qualities exist. The presence of this “unknown something,” underlying the sensible qualities, is what gives the peach “a title to be call’d one thing” (T 1.4.3.5; SBN 221).

Hume thinks that this underlying substance or “unknown something” is a fiction, characteristic of ancient philosophy (T 1.4.3.1, 1.4.3.5; SBN 219, 221). It is “feign[ed],” or postulated, by the exclusive imagination. Hume also calls this fiction an “unintelligible chimera” (T 1.4.3.7; SBN 222). Elsewhere, he explains the sense in which it is unintelligible. All of our ideas are copied from our impressions, or are made up of ideas that are so copied. But an underlying substance is supposed to be an entirely different kind of thing from an impression. So, we cannot form an idea of an underlying substance (T 1.4.5.3; SBN 232–3).

Does this mean that we cannot think about underlying substances at all? When Hume introduces the concept of an idea, he equates having ideas with thinking. This suggests that the answer is yes—the fact that we cannot form an idea of an underlying substance does mean that we cannot think about such substances at all.

However, other things that Hume says cast doubt on this interpretation. He seems to posit several different fictions that cannot be made up of ideas copied from impressions. For example, the “unintelligible” fiction of an underlying substance differs from the “incomprehensible” fiction of a perfect standard of equality (T 1.2.4.24; SBN 47–49). But how can entertaining one of these fictions differ from entertaining the other if, in each case, we have no thought at all about the thing that we are feigning, or fictitiously representing? Some commentators solve this puzzle by pointing to passages where Hume seems to distinguish two kinds of imaginative thought: conceiving and supposing (T 1.2.6.8–9, 1.4.2.56; SBN 67–68, 218). Hume seems to equate conceiving with forming ideas (T 1.2.2.8; SBN 32). This leaves open the possibility that supposing is a kind of imaginative thought that does not involve forming ideas. If this is Hume’s view, then he can allow that we can think about underlying substances and perfect standards of equality by making suppositions about them, even though we cannot conceive them or form ideas that represent them. For an interpretation of this kind, see Wilbanks (1968). For a helpful discussion of the problem posed by “unintelligible” fictions, and a creative solution, see Loeb (2002: chapter 5, esp. 162–72).

6. Imaginability and Possibility

Hume holds that whatever can be clearly (and, he sometimes adds, distinctly) conceived is possible. Scholars often call this his Conceivability Principle. Superficially, it resembles a principle that Descartes accepts: “everything which I clearly and distinctly understand is capable of being created by God so as to correspond exactly with my understanding of it” (Descartes, Sixth Meditation; CSM 2:54). But there are important differences between them. In Descartes’s view, our clearest and most distinct conceptions are due to our “pure understanding” or “pure intellect”—a faculty by which we form completely non-sensory, non-imagistic ideas—whereas “our sensory grasp” of things “is in many cases . . . obscure and confused” (Sixth Meditation; CSM 2:55); see section (2e) above. Therefore, in his Meditations, Descartes aims to help his readers achieve clear and distinct conceptions of the soul and the body by leading their minds away from the senses and imagination (as he explains in the Synopsis to the Meditations). In contrast, Hume writes that our impressions—the perceptions that our internal and external senses present to our minds—are “clear and evident” (T 1.2.3.1; SBN 33). And he equates clear and distinct conceivability with imaginability, as this passage makes clear:

’Tis an establish’d maxim in metaphysics, that whatever the mind clearly conceives includes the idea of possible existence, or in other words, that nothing we imagine is absolutely impossible. (T 1.2.2.8; SBN 32, italics in original)

Unlike Descartes’s principle, then, Hume’s Conceivability Principle means that whatever can be clearly (and distinctly) imagined is possible. (Hume does not specify whether he has the inclusive or exclusive imagination in mind. Likely, he thinks that any clear idea formed in the inclusive imagination—be it by reason, or by the exclusive imagination—represents something that is possible.)