Gottfried Leibniz: Philosophy of Mind

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) was a true polymath: he made substantial contributions to a host of different fields such as mathematics, law, physics, theology, and most subfields of philosophy. Within the philosophy of mind, his chief innovations include his rejection of the Cartesian doctrines that all mental states are conscious and that non-human animals lack souls as well as sensation. Leibniz’s belief that non-rational animals have souls and feelings prompted him to reflect much more thoroughly than many of his predecessors on the mental capacities that distinguish human beings from lower animals. Relatedly, the acknowledgment of unconscious mental representations and motivations enabled Leibniz to provide a far more sophisticated account of human psychology. It also led Leibniz to hold that perception—rather than consciousness, as Cartesians assume—is the distinguishing mark of mentality.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) was a true polymath: he made substantial contributions to a host of different fields such as mathematics, law, physics, theology, and most subfields of philosophy. Within the philosophy of mind, his chief innovations include his rejection of the Cartesian doctrines that all mental states are conscious and that non-human animals lack souls as well as sensation. Leibniz’s belief that non-rational animals have souls and feelings prompted him to reflect much more thoroughly than many of his predecessors on the mental capacities that distinguish human beings from lower animals. Relatedly, the acknowledgment of unconscious mental representations and motivations enabled Leibniz to provide a far more sophisticated account of human psychology. It also led Leibniz to hold that perception—rather than consciousness, as Cartesians assume—is the distinguishing mark of mentality.

The capacities that make human minds superior to animal souls, according to Leibniz, include not only their capacity for more elevated types of perceptions or mental representations, but also their capacity for more elevated types of appetitions or mental tendencies. Self-consciousness and abstract thought are examples of perceptions that are exclusive to rational souls, while reasoning and the tendency to do what one judges to be best overall are examples of appetitions of which only rational souls are capable. The mental capacity for acting freely is another feature that sets human beings apart from animals and it in fact presupposes the capacity for elevated kinds of perceptions as well as appetitions.

Another crucial contribution to the philosophy of mind is Leibniz’s frequently cited mill argument. This argument is supposed to show, through a thought experiment that involves walking into a mill, that material things such as machines or brains cannot possibly have mental states. Only immaterial things, that is, soul-like entities, are able to think or perceive. If this argument succeeds, it shows not only that our minds must be immaterial or that we must have souls, but also that we will never be able to construct a computer that can truly think or perceive.

Finally, Leibniz’s doctrine of pre-established harmony also marks an important innovation in the history of the philosophy of mind. Like occasionalists, Leibniz denies any genuine interaction between body and soul. He agrees with them that the fact that my foot moves when I decide to move it, as well as the fact that I feel pain when my body gets injured, cannot be explained by a genuine causal influence of my soul on my body, or of my body on my soul. Yet, unlike occasionalists, Leibniz also rejects the idea that God continually intervenes in order to produce the correspondence between my soul and my body. That, Leibniz thinks, would be unworthy of God. Instead, God has created my soul and my body in such a way that they naturally correspond to each other, without any interaction or divine intervention. My foot moves when I decide to move it because this motion has been programmed into it from the very beginning. Likewise, I feel pain when my body is injured because this pain was programmed into my soul. The harmony or correspondence between mental states and states of the body is therefore pre-established.

Table of Contents

- Leibnizian Minds and Mental States

- Freedom

- The Mill Argument

- The Relation between Mind and Body

- References and Further Reading

1. Leibnizian Minds and Mental States

Leibniz is a panpsychist: he believes that everything, including plants and inanimate objects, has a mind or something analogous to a mind. More specifically, he holds that in all things there are simple, immaterial, mind-like substances that perceive the world around them. Leibniz calls these mind-like substances ‘monads.’ While all monads have perceptions, however, only some of them are aware of what they perceive, that is, only some of them possess sensation or consciousness. Even fewer monads are capable of self-consciousness and rational perceptions. Leibniz typically refers to monads that are capable of sensation or consciousness as ‘souls,’ and to those that are also capable of self-consciousness and rational perceptions as ‘minds.’ The monads in plants, for instance, lack all sensation and consciousness and are hence neither souls nor minds; Leibniz sometimes calls this least perfect type of monad a ‘bare monad’ and compares the mental states of such monads to our states when we are in a stupor or a dreamless sleep. Animals, on the other hand, can sense and be conscious, and thus possess souls (see Animal Minds). God and the souls of human beings and angels, finally, are examples of minds because they are self-conscious and rational. As a result, even though there are mind-like things everywhere for Leibniz, minds in the stricter sense are not ubiquitous.

All monads, even those that lack consciousness altogether, have two basic types of mental states: perceptions, that is, representations of the world around them, and appetitions, or tendencies to transition from one representation to another. Hence, even though monads are similar to the minds or souls described by Descartes in some ways—after all, they are immaterial substances—consciousness is not an essential property of monads, while it is an essential property of Cartesian souls. For Leibniz, then, the distinguishing mark of mentality is perception, rather than consciousness (see Simmons 2001). In fact, even Leibnizian minds in the stricter sense, that is, monads capable of self-consciousness and reasoning, are quite different from the minds in Descartes’s system. While Cartesian minds are conscious of all their mental states, Leibnizian minds are conscious only of a small portion of their states. To us it may seem obvious that there is a host of unconscious states in our minds, but in the seventeenth century this was a radical and novel notion. This profound departure from Cartesian psychology allows Leibniz to paint a much more nuanced picture of the human mind.

One crucial aspect of Leibniz’s panpsychism is that in addition to the rational monad that is the soul of a human being, there are non-rational, bare monads everywhere in the human being’s body. Leibniz sometimes refers to the soul of a human being or animal as the central or dominant monad of the organism. The bare monads that are in an animal’s body, accordingly, are subordinate to its dominant monad or soul. Even plants, for Leibniz, have central or dominant monads, but because they lack sensation, these dominant monads cannot strictly speaking be called souls. They are merely bare monads, like the monads that are subordinate to them.

The claim that there are mind-like things everywhere in nature—in our bodies, in plants, and even in inanimate objects—strikes many readers of Leibniz as ludicrous. Yet, Leibniz thinks he has conclusive metaphysical arguments for this claim. Very roughly, he holds that a complex, divisible thing such as a body can only be real if it is made up of parts that are real. If the parts in turn have parts, those have to be real as well. The problem is, Leibniz claims, that matter is infinitely divisible: we can never reach parts that do not themselves have parts. Even if there were material atoms that we cannot actually divide, they must still be spatially extended, like all matter, and therefore have spatial parts. If something is spatially extended, after all, we can at least in thought distinguish its left half from its right half, no matter how small it is. As a result, Leibniz thinks, purely material things are not real. The reality of complex wholes depends on the reality of their parts, but with purely material things, we never get to parts that are real since we never reach an end in this quest for reality. Leibniz concludes that there must be something in nature that is not material and not divisible, and from which all things derive their reality. These immaterial, indivisible things just are monads. Because of the role they play, Leibniz sometimes describes them as “atoms of substance, that is, real unities absolutely destitute of parts, […] the first absolute principles of the composition of things, and, as it were, the final elements in the analysis of substantial things” (p. 142. For a more thorough description of monads, see Leibniz: Metaphysics, as well as the Monadology and the New System of Nature, both included in Ariew and Garber.)

a. Perceptions

As already seen, all monads have perceptions, that is, they represent the world around them. Yet, not all perceptions—not even all the perceptions of minds—are conscious. In fact, Leibniz holds that at any given time a mind has infinitely many perceptions, but is conscious only of a very small number of them. Even souls and bare monads have an infinity of perceptions. This is because Leibniz believes, for reasons that need not concern us here (but see Leibniz: Metaphysics), that each monad constantly perceives the entire universe. For instance, even though I am not aware of it at all, my mind is currently representing every single grain of sand on Mars. Even the monads in my little toe, as well as the monads in the apple I am about to eat, represent those grains of sand.

Leibniz often describes perceptions of things of which the subject is unaware and which are far removed from the subject’s body as ‘confused.’ He is fond of using the sound of the ocean as a metaphor for this kind of confusion: when I go to the beach, I do not hear the sound of each individual wave distinctly; instead, I hear a roaring sound from which I am unable to discern the sounds of the individual waves (see Principles of Nature and Grace, section 13, in Ariew and Garber, 1989). None of these individual sounds stands out. Leibniz claims that confused perceptions in monads are analogous to this confusion of sounds, except of course for the fact that monads do not have to be aware even of the confused whole. To the extent that a perception does stand out from the rest, however, Leibniz calls it ‘distinct.’ This distinctness comes in degrees, and Leibniz claims that the central monads of organisms always perceive their own bodies more distinctly than they perceive other bodies.

Bare monads are not capable of very distinct perceptions; their perceptual states are always muddled and confused to a high degree. Animal souls, on the other hand, can have much more distinct perceptions than bare monads. This is in part because they possess sense organs, such as eyes, which allow them to bundle and condense information about their surroundings (see Principles of Nature and Grace, section 4). The resulting perceptions are so distinct that the animals can remember them later, and Leibniz calls this kind of perception ‘sensation.’ The ability to remember prior perceptions is extremely useful, as a matter of fact, because it enables animals to learn from experience. For instance, a dog that remembers being beaten with a stick can learn to avoid sticks in the future (see Principles of Nature and Grace, section 5, in Ariew and Garber, 1989). Sensations are also tied to pleasure and pain: when an animal distinctly perceives some imperfection in its body, such as a bruise, this perception just is a feeling of pain. Similarly, when an animal perceives some perfection of its body, such as nourishment, this perception is pleasure. Unlike Descartes, then, Leibniz believed that animals are capable of feeling pleasure and pain.

Consequently, souls differ from bare monads in part through the distinctness of their perceptions: unlike bare monads, souls can have perceptions that are distinct enough to give rise to memory and sensation, and they can feel pleasure and pain. Rational souls, or minds, share these capacities. Yet they are additionally capable of perceptions of an even higher level. Unlike the souls of lower animals, they can reflect on their own mental states, think abstractly, and acquire knowledge of necessary truths. For instance, they are capable of understanding mathematical concepts and proofs. Moreover, they can think of themselves as substances and subjects: they have the ability to use and understand the word ‘I’ (see Monadology, section 30). These kinds of perceptions, for Leibniz, are distinctively rational perceptions, and they are exclusive to minds or rational souls.

It is clear, then, that there are different types of perceptions: some are unconscious, some are conscious, and some constitute reflection or abstract thought. What exactly distinguishes these types of perceptions, however, is a complicated question that warrants a more detailed investigation.

i. Consciousness, Apperception, and Reflection

Why are some perceptions conscious, while others are not? In one text, Leibniz explains the difference as follows: “it is good to distinguish between perception, which is the internal state of the monad representing external things, and apperception, which is consciousness, or the reflective knowledge of this internal state, something not given to all souls, nor at all times to a given soul” (Principles of Nature and Grace, section 4). This passage is interesting for several reasons: Leibniz not only equates consciousness with what he calls ‘apperception,’ and states that only some monads possess it. He also seems to claim that conscious perceptions differ from other perceptions in virtue of having different types of things as their objects: while unconscious perceptions represent external things, apperception or consciousness has perceptions, that is, internal things, as its object. Consciousness is therefore closely connected to reflection, as the term ‘reflective knowledge’ also makes clear.

The passage furthermore suggests that Leibniz understands consciousness in terms of higher-order mental states because it says that in order to be conscious of a perception, I must possess “reflective knowledge” of that perception. One way of interpreting this statement is to understand these higher-order mental states as higher-order perceptions: in order to be conscious of a first-order perception, I must additionally possess a second-order perception of that first-order perception. For example, in order to be conscious of the glass of water in front of me, I must not only perceive the glass of water, but I must also perceive my perception of the glass of water. After all, in the passage under discussion, Leibniz defines ‘consciousness’ or ‘apperception’ as the reflective knowledge of a perception. Such higher-order theories of consciousness are still endorsed by some philosophers of mind today (see Consciousness). For an alternative interpretation of Leibniz’s theory of consciousness, however, see Jorgensen 2009, 2011a, and 2011b).

There is excellent textual evidence that according to Leibniz, consciousness or apperception is not limited to minds, but is instead shared by animal souls. One passage in which Leibniz explicitly ascribes apperception to animals is from the New Essays: “beasts have no understanding … although they have the faculty for apperceiving the more conspicuous and outstanding impressions—as when a wild boar apperceives someone who is shouting at it” (p. 173). Moreover, Leibniz sometimes claims that sensation involves apperception (e.g. New Essays p. 161; p. 188), and since animals are clearly capable of sensation, they must thus possess some form of apperception. Hence, it seems that Leibniz ascribes apperception to animals, which in turn he elsewhere identifies with consciousness.

Yet, the textual evidence for animal consciousness is unfortunately anything but neat because in the New Essays—that is, in the very same text—Leibniz also suggests that there is an important difference between animals and human beings somewhere in this neighborhood. In several passages, he says that any creature with consciousness has a moral or personal identity, which in turn is something he grants only to minds. He states, for instance, that “consciousness or the sense of I proves moral or personal identity” (New Essays, p. 236). Hence, it seems clear that for Leibniz there is something in the vicinity of consciousness that animals lack and that minds possess, and which is crucial for morality.

A promising solution to this interpretive puzzle is the following: what animals lack is not consciousness generally, but only a particular type of consciousness. More specifically, while they are capable of consciously perceiving external things, they lack awareness, or at least a particular type of awareness, of the self. In the Monadology, for instance, Leibniz argues that knowledge of necessary truths distinguishes us from animals and that through this knowledge “we rise to reflexive acts, which enable us to think of that which is called ‘I’ and enable us to consider that this or that is in us” (sections 29-30). Similarly, he writes in the Principles of Nature and Grace that “minds … are capable of performing reflective acts, and capable of considering what is called ‘I’, substance, soul, mind—in brief, immaterial things and immaterial truths” (section 5). Self-knowledge, or self-consciousness, then, appears to be exclusive to rational souls. Leibniz moreover connects this consciousness of the self to personhood and moral responsibility in several texts, such as for instance in the Theodicy: “In saying that the soul of man is immortal one implies the subsistence of what makes the identity of the person, something which retains its moral qualities, conserving the consciousness, or the reflective inward feeling, of what it is: thus it is rendered susceptible to chastisement or reward” (section 89).

Based on these passages, it seems that one crucial cognitive difference between human beings and animals is that even though animals possess the kind of apperception that is involved in sensation and in an acute awareness of external objects, they lack a certain type of apperception or consciousness, namely reflective self-knowledge or self-consciousness. Especially because of the moral implications of this kind of consciousness that Leibniz posits, this difference is clearly an extremely important one. According to these texts, then, it is not consciousness or apperception tout court that distinguishes minds from animal souls, but rather a particular kind of apperception. What animals are incapable of, according to Leibniz, is self-knowledge or self-awareness, that is, an awareness not only of their perceptions, but also of the self that is having those perceptions.

Because Leibniz associates consciousness so closely with reflection, one might wonder whether the fact that animals are capable of conscious perceptions implies that they are also capable of reflection. This is another difficult interpretive question because there appears to be evidence both for a positive and for a negative answer. Reflection, according to Leibniz, is “nothing but attention to what is within us” (New Essays, p. 51). Moreover, as already seen, he argues that reflective acts enable us “to think of that which is called ‘I’ and … to consider that this or that is in us” (Monadology, section 30). Leibniz does not appear to ascribe reflection to animals explicitly, and in fact, there are several texts in which he says in no uncertain terms that they lack reflection altogether. He states for instance that “the soul of a beast has no more reflection than an atom” (Loemker, p. 588). Likewise, he defines ‘intellection’ as “a distinct perception combined with a faculty of reflection, which the beasts do not have” (New Essays, p. 173) and explains that “just as there are two sorts of perception, one simple, the other accompanied by reflections that give rise to knowledge and reasoning, so there are two kinds of souls, namely ordinary souls, whose perception is without reflection, and rational souls, which think about what they do” (Strickland, p. 84).

On the other hand, as seen, Leibniz does ascribe apperception or consciousness to animals, and consciousness in turn appears to involve higher-order mental states. This suggests that Leibnizian animals must perceive or know their own perceptions when they are conscious of something, and that in turn seems to imply that they can reflect after all. A closely related reason for ascribing reflection to animals is that Leibniz sometimes explicitly associates reflection with apperception or consciousness. In a passage already quoted above, for instance, Leibniz defines ‘consciousness’ as the reflective knowledge of a first-order perception. Hence, if animals possess consciousness it seems that they must also have some type of reflection.

We are consequently faced with an interpretive puzzle: even though there is strong indirect evidence that Leibniz attributes reflection to animals, there is also direct evidence against it. There are at least two ways of solving this puzzle. In order to make sense of passages in which Leibniz restricts reflection to rational souls, one can either deny that perceiving one’s internal states is sufficient for reflection, or one can distinguish between different types of reflection, in such a way that the most demanding type of reflection is limited to minds. One good way to deny that perception of one’s internal states is sufficient for reflection is to point out that Leibniz defines reflection as “attention to what is within us” (New Essays, p. 51), rather than as ‘perception of what is within us.’ Attention to internal states, arguably, is more demanding than mere perception of these states, and animals may well be incapable of the former. Attention might be a particularly distinct perception, for instance. Alternatively, one can argue that reflection requires a self-concept, or self-knowledge, which also goes beyond the mere perception of internal states and may be inaccessible to animals. Perceiving my internal states, on that interpretation, amounts to reflection only if I also possess knowledge of the self that is having those states. Instead of denying that perceiving one’s own states is sufficient for reflection, one can also distinguish different types of reflection and claim that while the mere perception of one’s internal states is a type of reflection, there is a more demanding type of reflection that requires attention, a self-concept, or something similar. Yet, the difference between those two responses appears to be merely terminological. Based on the textual evidence discussed above, it is clear that either reflection generally, or at least a particular type of reflection, must be exclusive to minds.

ii. Abstract Thought, Concepts, and Universal Truths

So far, we have seen that one cognitive capacity that elevates minds above animal souls is self-consciousness, which is a particular type of reflection. Before turning to appetitions, we should briefly investigate three additional, mutually related, cognitive abilities that only minds possess, namely the abilities to abstract, to form or possess concepts, and to know general truths. In what may well be Leibniz’s most intriguing discussion of abstraction, he says that some non-human animals “apparently recognize whiteness, and observe it in chalk as in snow; but it does not amount to abstraction, which requires attention to the general apart from the particular, and consequently involves knowledge of universal truths which beasts do not possess” (New Essays, p. 142). In this passage, we learn not only that beasts are incapable of abstraction, but also that abstraction involves “attention to the general apart from the particular” as well as “knowledge of universal truths.” Hence, abstraction for Leibniz seems to consist in separating out one part of a complex idea and focusing on it exclusively. Instead of thinking of different white things, one must think of whiteness in general, abstracting away from the particular instances of whiteness. In order to think about whiteness in the abstract, then, it is not enough to perceive different white things as similar to one another.

Yet, it might still seem mysterious how precisely animals should be able to observe whiteness in different objects if they are unable to abstract. One fact that makes this less mysterious, however, is that, on Leibniz’s view, while animals are unable to pay attention to whiteness in general, the idea of whiteness may nevertheless play a role in their recognition of whiteness. As Leibniz explains in the New Essays, even though human minds are aware of complex ideas and particular truths first as well as rather easily, and have to expend a lot of effort to subsequently achieve awareness of simple ideas and general principles, the order of nature is the other way around:

The truths that we start by being aware of are indeed particular ones, just as we start with the coarsest and most composite ideas. But that doesn’t alter the fact that in the order of nature the simplest comes first, and that the reasons for particular truths rest wholly on the more general ones of which they are mere instances. … The mind relies on these principles constantly; but it does not find it so easy to sort them out and to command a distinct view of each of them separately, for that requires great attention to what it is doing. (p. 83f.)

Here, Leibniz says that minds can rely on general principles, or abstract ideas, without being aware of them, and without having distinct perceptions of them separately. This might help us to explain how animals can observe whiteness in different white objects without being able to abstract: the simple idea of whiteness might play a role in their cognition, even though they are not aware of it, and are unable to pay attention to this idea.

The passage just quoted is interesting for another reason: It shows that abstracting and achieving knowledge of general truths have a lot in common and presuppose the capacity to reflect. It takes a special effort of mind to become aware of abstract ideas and general truths, that is, to separate these out from complex ideas and particular truths. It is this special effort, it seems, of which animals are incapable; while they can at times achieve relatively distinct perceptions of complex or particular things, they lack the ability to pay attention, or at least sufficient attention, to their internal states. At least part of the reason for their inability to abstract and to know general truths, then, appears to be their inability, or at least very limited ability, to reflect.

Abstraction also seems closely related to the possession or formation of concepts: arguably, what a mind gains when abstracting the idea of whiteness from the complex ideas of particular white things is what we would call a concept of whiteness. Hence, since animals cannot abstract, they do not possess such concepts. They may nevertheless, as suggested above, have confused ideas such as a confused idea of whiteness that allows them to recognize whiteness in different white things, without enabling them to pay attention to whiteness in the abstract.

An interesting question that arises in this context is the question whether having an idea of the future or thinking about a future state requires abstraction. One reason to think so is that, plausibly, in order to think about the future, for instance about future pleasures or pains, one needs to abstract from the present pleasures or pains that one can directly experience, or from past pleasures and pains that one remembers. After all, just as one can only attain the concept of whiteness by abstracting from other properties of the particular white things one has experienced, so, arguably, one can only acquire the idea of future pleasures through abstraction from particular present pleasures. It may be for this reason that Leibniz sometimes notes that animals have “neither foresight nor anxiety for the future” (Huggard, p. 414). Apparently, he does not consider animals capable of having an idea of the future or of future states.

Leibniz thinks that in addition to sensible concepts such as whiteness, we also have concepts that are not derived from the senses, that is, we possess intellectual concepts. The latter, it seems, set us apart even farther from animals because we attain them through reflective self-awareness, of which animals, as seen above, are not capable. Leibniz says, for instance, that “being is innate in us—the knowledge of being is comprised in the knowledge that we have of ourselves. Something like this holds of other general notions” (New Essays, p. 102). Similarly, he states a few pages later that “reflection enables us to find the idea of substance within ourselves, who are substances” (New Essays, p. 105). Many similar statements can be found elsewhere. The intellectual concepts that we can discover in our souls, according to Leibniz, include not only being and substance, but also unity, similarity, sameness, pleasure, cause, perception, action, duration, doubting, willing, and reasoning, to name only a few. In order to derive these concepts from our reflective self-awareness, we must apparently engage in abstraction: I am distinctly aware of myself as an agent, a substance, and a perceiver, for instance, and from this awareness I can abstract the ideas of action, substance, and perception in general. This means that animals are inferior to us among other things in the following two ways: they cannot have distinct self-awareness, and they cannot abstract. They would need both of these capacities in order to form intellectual concepts, and they would need the latter—that is, abstraction—in order to form sensible concepts.

Intellectual concepts are not the only things that minds can find in themselves: in addition, they are also able to discover eternal or general truths there, such as the axioms or principles of logic, metaphysics, ethics, and natural theology. Like the intellectual concepts just mentioned, these general truths or principles cannot be derived from the senses and can thus be classified as innate ideas. Leibniz says, for instance,

Above all, we find [in this I and in the understanding] the force of the conclusions of reasoning, which are part of what is called the natural light. … It is also by this natural light that the axioms of mathematics are recognized. … [I]t is generally true that we know [necessary truths] only by this natural light, and not at all by the experiences of the senses. (Ariew and Garber, p. 189)

Axioms and general principles, according to this passage, must come from the mind itself and cannot be acquired through sense experience. Yet, also as in the case of intellectual concepts, it is not easy for us to discover such general truths or principles in ourselves; instead, it takes effort or special attention. It again appears to require the kind of attention to what is within us of which animals are not capable. Because they lack this type of reflection, animals are “governed purely by examples from the senses” and “consequently can never arrive at necessary and general truths” (Strickland p. 84).

b. Appetitions

Monads possess not only perceptions, or representations of the world they inhabit, but also appetitions. These appetitions are the tendencies or inclinations of these monads to act, that is, to transition from one mental state to another. The most familiar examples of appetitions are conscious desires, such as my desire to have a drink of water. Having this desire means that I have some tendency to drink from the glass of water in front of me. If the desire is strong enough, and if there are no contrary tendencies or desires in my mind that are stronger—for instance, the desire to win the bet that I can refrain from drinking water for one hour—I will attempt to drink the water. This desire for water is one example of a Leibnizian appetition. Yet, just as in the case of perceptions, only a very small portion of appetitions is conscious. We are unaware of most of the tendencies that lead to changes in our perceptions. For instance, I am aware neither of perceiving my hair growing, nor of my tendencies to have those perceptions. Moreover, as in the case of perceptions, there are an infinite number of appetitions in any monad at any given time. This is because, as seen, each monad represents the entire universe. As a result, each monad constantly transitions from one infinitely complex perceptual state to another, reflecting all changes that take place in the universe. The tendency that leads to a monad’s transition from one of these infinitely complex perceptual states to another is therefore also infinitely complex, or composed of infinitely many smaller appetitions.

The three types of monads—bare monads, souls, and minds—differ not only with respect to their perceptual or cognitive capacities, but also with respect to their appetitive capacities. In fact, there are good reasons to think that three different types of appetitions correspond to the three types of perceptions mentioned above, that is, to perception, sensation, and rational perception. After all, Leibniz distinguishes between appetitions of which we can be aware and those of which we cannot be aware, which he sometimes also calls ‘insensible appetitions’ or ‘insensible inclinations.’ He appears to further divide the type of which we can be aware into rational and non-rational appetitions. This threefold division is made explicit in a passage from the New Essays:

There are insensible inclinations of which we are not aware. There are sensible ones: we are acquainted with their existence and their objects, but have no sense of how they are constituted. … Finally there are distinct inclinations which reason gives us: we have a sense both of their strength and of their constitution. (p. 194)

According to this passage, then, Leibniz acknowledges the following three types of appetitions: (a) insensible or unconscious appetitions, (b) sensible or conscious appetitions, and (c) distinct or rational appetitions.

Even though Leibniz does not say so explicitly, he furthermore believes that bare monads have only unconscious appetitions, that animal souls additionally have conscious appetitions, and that only minds have distinct or rational appetitions. Unconscious appetitions are tendencies such as the one that leads to my perception of my hair growing, or the one that prompts me unexpectedly to perceive the sound of my alarm in the morning. All appetitions in bare monads are of this type; they are not aware of any of their tendencies. An example of a sensible appetition, on the other hand, is an appetition for pleasure. My desire for a piece of chocolate, for instance, is such an appetition: I am aware that I have this desire and I know what the object of the desire is, but I do not fully understand why I have it. Animals are capable of this kind of appetition; in fact, many of their actions are motivated by their appetitions for pleasure. Finally, an example of a rational appetition is the appetition for something that my intellect has judged to be the best course of action. Leibniz appears to identify the capacity for this kind of appetition with the will, which, as we will see below, plays a crucial role in Leibniz’s theory of freedom. What is distinctive of this kind of appetition is that whenever we possess it, we are not only aware of it and of its object, but also understand why we have it. For instance, if I judge that I ought to call my mother and consequently desire to call her, Leibniz thinks, I am aware of the thought process that led me to make this judgment, and hence of the origins of my desire.

Another type of rational appetition is the type of appetition involved in reasoning. As seen, Leibniz thinks that animals, because they can remember prior perceptions, are able to learn from experience, like the dog that learns to run away from sticks. This sort of behavior, which involves a kind of inductive inference (see Deductive and Inductive Arguments), can be called a “shadow of reasoning,” Leibniz tells us (New Essays, p. 50). Yet, animals are incapable of true—that is, presumably, deductive—reasoning, which, Leibniz tells us, “depends on necessary or eternal truths, such as those of logic, numbers, and geometry, which bring about an indubitable connection of ideas and infallible consequences” (Principles of Nature and Grace, section 5, in Ariew and Garber, 1989). Only minds can reason in this stricter sense.

Some interpreters think that reasoning consists simply in very distinct perception. Yet that cannot be the whole story. First of all, reasoning must involve a special type of perception that differs from the perceptions of lower animals in kind, rather than merely in degree, namely abstract thought and the perception of eternal truths. This kind of perception is not just more distinct; it has entirely different objects than the perceptions of non-rational souls, as we saw above. Moreover, it seems more accurate to describe reasoning as a special kind of appetition or tendency than as a special kind of perception. This is because reasoning is not just one perception, but rather a series of perceptions. Leibniz for instance calls it “a chain of truths” (New Essays, p. 199) and defines it as “the linking together of truths” (Huggard, p. 73). Thus, reasoning is not the same as perceiving a certain type of object, nor as perceiving an object in a particular fashion. Rather, it consists mainly in special types of transitions between perceptions and therefore, according to Leibniz’s account of how monads transition from perception to perception, in appetitions for these transitions. What a mind needs in order to be rational, therefore, are appetitions that one could call the principles of reasoning. These appetitions or principles allow minds to transition, for instance, from the premises of an argument to its conclusion. In order to conclude ‘Socrates is mortal’ from ‘All men are mortal’ and ‘Socrates is a man,’ for example, I not only need to perceive the premises distinctly, but I also need an appetition for transitioning from premises of a particular form to conclusions of a particular form.

Leibniz states in several texts that our reasonings are based on two fundamental principles: the Principle of Contradiction and the Principle of Sufficient Reason. Human beings also have access to several additional innate truths and principles, for instance those of logic, mathematics, ethics, and theology. In virtue of these principles we have a priori knowledge of necessary connections between things, while animals can only have empirical knowledge of contingent, or merely apparent, connections. The perceptions of animals, then, are not governed by the principles on which our reasonings are based; the closest an animal can come to reasoning is, as mentioned, engaging in empirical inference or induction, which is based not on principles of reasoning, but merely on the recognition and memory of regularities in previous experience. This confirms that reasoning is a type of appetition: using, or being able to use, principles of reasoning cannot just be a matter of perceiving the world more distinctly. In fact, these principles are not something that we acquire or derive from perceptions. Instead, at least the most basic ones are innate dispositions for making certain kinds of transitions.

In connection with reasoning, it is important to note that even though Leibniz sometimes uses the term ‘thought’ for perceptions generally, he makes it clear in some texts that it strictly speaking belongs exclusively to minds because it is “perception joined with reason” (Strickland p. 66; see also New Essays, p. 210). This means that the ability to think in this sense, just like reasoning, is also something that is exclusive to minds, that is, something that distinguishes minds from animal souls. Non-rational souls neither reason nor think, strictly speaking; they do however have perceptions.

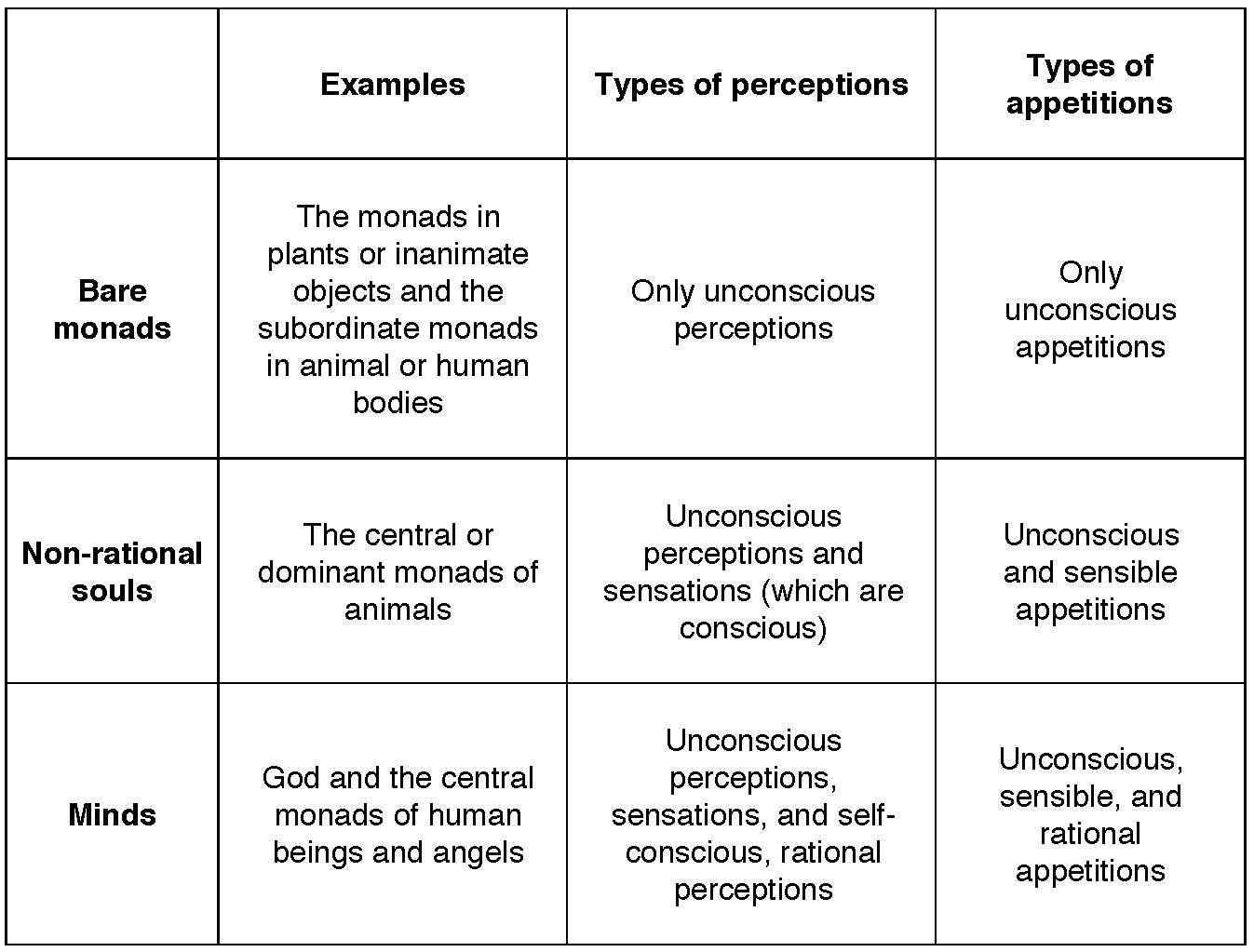

The distinctive cognitive and appetitive capacities of the three types of monads are summarized in the following table:

2. Freedom

One final capacity that sets human beings apart from non-rational animals is the capacity for acting freely. This is mainly because Leibniz closely connects free agency with rationality: acting freely requires acting in accordance with one’s rational assessment of which course of action is best. Hence, acting freely involves rational perceptions as well as rational appetitions. It requires both knowledge of, or rational judgments about, the good, as well as the tendency to act in accordance with these judgments. For Leibniz, the capacity for rational judgments is called ‘intellect,’ and the tendency to pursue what the intellect judges to be best is called ‘will.’ Non-human animals, because they do not possess intellects and wills, or the requisite type of perceptions and appetitions, lack freedom. This also means, however, that most human actions are not free, because we only sometimes reason about the best course of action and act voluntarily, on the basis of our rational judgments. Leibniz in fact stresses that in three quarters of their actions, human beings act just like animals, that is, without making use of their rationality (see Principles of Nature and Grace, section 5, in Ariew and Garber, 1989).

In addition to rationality, Leibniz claims, free actions must be self-determined and contingent (see e.g. Theodicy, section 288). An action is self-determined—or spontaneous, as Leibniz often calls it—when its source is in the agent, rather than in another agent or some other external entity. While all actions of monads are spontaneous in a general sense since, as we will see in section four, Leibniz denies all interaction among created substances, he may have a more demanding notion of spontaneity in mind when he calls it a requirement for freedom. After all, when an agent acts on the basis of her rational judgment, she is not even subject to the kind of apparent influence of her body or of other creatures that is present, for instance, when someone pinches her and she feels pain.

In order to be contingent, on the other hand, the action cannot be the result of compulsion or necessitation. This, again, is generally true for all actions of monads because Leibniz holds that all changes in the states of a creature are contingent. Yet, there may again be an especially demanding sense in which free actions are contingent for Leibniz. He often says that when a rational agent does something because she believes it to be best, the goodness she perceives, or her motives for acting, merely incline her towards action without necessitating action (see e.g. Huggard, p. 419; Fifth Letter to Clarke, sections 8-9; Ariew and Garber, p. 195; New Essays, p. 175). Hence, Leibniz may be attributing a particular kind of contingency to free actions.

Even though Leibniz holds that free actions must be contingent, that is, that they cannot be necessary, he grants that they can be determined. In fact, Leibniz vehemently rejects the notion that a world with free agents must contain genuine indeterminacy. Hence, Leibniz is what we today call a compatibilist about freedom and determinism (see Free Will). He believes that all actions, whether they are free or not, are determined by the nature and the prior states of the agent. What is special about free actions, then, is not that they are undetermined, but rather that they are determined, among other things, by rational perceptions of the good. We always do what we are most strongly inclined to do, for Leibniz, and if we are most strongly inclined by our judgment about the best course of action, we pursue that course of action freely. The ability to act contrary even to one’s best reasons or motives, Leibniz contends, is not required for freedom, nor would it be worth having. As Leibniz puts it in the New Essays, “the freedom to will contrary to all the impressions which may come from the understanding … would destroy true liberty, and reason with it, and would bring us down below the beasts” (p. 180). In fact, being determined by our rational understanding of the good, as we are in our free actions, makes us godlike, because according to Leibniz, God is similarly determined by what he judges to be best. Nothing could be more perfect and more desirable than acting in this way.

3. The Mill Argument

In several of his writings, Leibniz argues that purely material things such as brains or machines cannot possibly think or perceive. Hence, Leibniz contends that materialists like Thomas Hobbes are wrong to think that they can explain mentality in terms of the brain. This argument is without question among Leibniz’s most influential contributions to the philosophy of mind. It is relevant not only to the question whether human minds might be purely material, but also to the question whether artificial intelligence is possible. Because Leibniz’s argument against perception in material objects often employs a thought experiment involving a mill, interpreters refer to it as ‘the mill argument.’ There is considerable disagreement among recent scholars about the correct interpretation of this argument (see References and Further Reading). The present section sketches one plausible way of interpreting Leibniz’s mill argument.

The most famous version of Leibniz’s mill argument occurs in section 17 of the Monadology:

Moreover, we must confess that perception, and what depends on it, is inexplicable in terms of mechanical reasons, that is, through shapes and motions. If we imagine that there is a machine whose structure makes it think, sense, and have perceptions, we could conceive it enlarged, keeping the same proportions, so that we could enter into it, as one enters into a mill. Assuming that, when inspecting its interior, we will only find parts that push one another, and we will never find anything to explain a perception. And so, we should seek perception in the simple substance and not in the composite or in the machine.

To understand this argument, it is important to recall that Leibniz, like many of his contemporaries, views all material things as infinitely divisible. As already seen, he holds that there are no smallest or most fundamental material elements, and every material thing, no matter how small, has parts and is hence complex. Even if there were physical atoms—against which Leibniz thinks he has conclusive metaphysical arguments—they would still have to be extended, like all matter, and we would hence be able to distinguish between an atom’s left half and its right half. The only truly simple things that exist are monads, that is, unextended, immaterial, mind-like things. Based on this understanding of material objects, Leibniz argues in the mill passage that only immaterial entities are capable of perception because it is impossible to explain perception mechanically, or in terms of material parts pushing one another.

Unfortunately Leibniz does not say explicitly why exactly he thinks there cannot be a mechanical explanation of perception. Yet it becomes clear in other passages that for Leibniz perceiving has to take place in a simple thing. This assumption, in turn, straightforwardly implies that matter—which as seen is complex—is incapable of perception. This, most likely, is behind Leibniz’s mill argument. Why does Leibniz claim that perception can only take place in simple things? If he did not have good reasons for this claim, after all, it would not constitute a convincing starting point for his mill argument.

Leibniz’s reasoning appears to be the following. Material things, such as mirrors or paintings, can represent complexity. When I stand in front of a mirror, for instance, the mirror represents my body. This is an example of the representation of one complex material thing in another complex material thing. Yet, Leibniz argues, we do not call such a representation ‘perception’: the mirror does not “perceive” my body. The reason this representation falls short of perception, Leibniz contends, is that it lacks the unity that is characteristic of perceptions: the top part of the mirror represents the top part of my body, and so on. The representation of my body in the mirror is merely a collection of smaller representations, without any genuine unity. When another person perceives my body, on the other hand, her representation of my body is a unified whole. No physical thing can do better than the mirror in this respect: the only way material things can represent anything is through the arrangement or properties of their parts. As a result, any such representation will be spread out over multiple parts of the representing material object and hence lack genuine unity. It is arguably for this reason that Leibniz defines ‘perception’ as “the passing state which involves and represents a multitude in the unity or in the simple substance” (Monadology, section 14).

Leibniz’s mill argument, then, relies on a particular understanding of perception and of material objects. Because all material objects are complex and because perceptions require unity, material objects cannot possibly perceive. Any representation a machine, or a material object, could produce would lack the unity required for perception. The mill example is supposed to illustrate this: even an extremely small machine, if it is purely material, works only in virtue of the arrangement of its parts. Hence, it is always possible, at least in principle, to enlarge the machine. When we imagine the machine thus enlarged, that is, when we imagine being able to distinguish the machine’s parts as we can distinguish the parts of a mill, we will realize that the machine cannot possibly have genuine perceptions.

Yet the basic idea behind Leibniz’s mill argument can be appealing even to those of us who do not share Leibniz’s assumptions about perception and material objects. In fact, it appears to be a more general version of what is today called “the hard problem of consciousness,” that is, the problem of explaining how something physical could explain, or give rise to, consciousness. While Leibniz’s mill argument is about perception generally, rather than conscious perception in particular, the underlying structure of the argument appears to be similar: mental states have characteristics—such as their unity or their phenomenal properties—that, it seems, cannot even in principle be explained physically. There is an explanatory gap between the physical and the mental.

4. The Relation between Mind and Body

The mind-body problem is a central issue in the philosophy of mind. It is, roughly, the problem of explaining how mind and body can causally interact. That they interact seems exceedingly obvious: my mental states, such as for instance my desire for a cold drink, do seem capable of producing changes in my body, such as the bodily motions required for walking to the fridge and retrieving a bottle of water. Likewise, certain physical states seem capable of producing changes in my mind: when I stub my toe on my way to the fridge, for instance, this event in my body appears to cause me pain, which is a mental state. For Descartes and his followers, it is notoriously difficult to explain how mind and body causally interact. After all, Cartesians are substance dualists: they believe that mind and body are substances of a radically different type (see Descartes: Mind-Body Distinction). How could a mental state such as a desire cause a physical state such as a bodily motion, or vice versa, if mind and body have absolutely nothing in common? This is the version of the mind-body problem that Cartesians face.

For Leibniz, the mind-body problem does not arise in exactly the way it arises for Descartes and his followers, because Leibniz is not a substance dualist. We have already seen that, according to Leibniz, an animal or human being has a central monad, which constitutes its soul, as well as subordinate monads that are everywhere in its body. In fact, Leibniz appears to hold that the body just is the collection of these subordinate monads and their perceptions (see e.g. Principles of Nature and Grace section 3), or that bodies result from monads (Ariew and Garber, p. 179). After all, as already seen, he holds that purely material, extended things would not only be incapable of perception, but would also not be real because of their infinite divisibility. The only truly real things, for Leibniz, are monads, that is, immaterial and indivisible substances. This means that Leibniz, unlike Descartes, does not believe that there are two fundamentally different kinds of substances, namely physical and mental substances. Instead, for Leibniz, all substances are of the same general type. As a result, the mind-body problem may seem more tractable for Leibniz: if bodies have a semi-mental nature, there are fewer obvious obstacles to claiming that bodies and minds can interact with one another.

Yet, for complicated reasons that are beyond the scope of this article (but see Leibniz: Causation), Leibniz held that human minds and their bodies—as well as any created substances, in fact—cannot causally interact. In this, he agrees with occasionalists such as Nicolas Malebranche. Leibniz departs from occasionalists, however, in his positive account of the relation between mental and corresponding bodily events. Occasionalists hold that God needs to intervene in nature constantly to establish this correspondence. When I decide to move my foot, for instance, God intervenes and moves my foot accordingly, occasioned by my decision. Leibniz, however, thinks that such interventions would constitute perpetual miracles and be unworthy of a God who always acts in the most perfect manner. God arranged things so perfectly, Leibniz contends, that there is no need for these divine interventions. Even though he endorses the traditional theological doctrine that God continually conserves all creatures in existence and concurs with their actions (see Leibniz: Causation), Leibniz stresses that all natural events in the created world are caused and made intelligible by the natures of created things. In other words, Leibniz rejects the occasionalist doctrine that God is the only active, efficient cause, and that the laws of nature that govern natural events are merely God’s intentions to move his creatures around in a particular way. Instead for Leibniz these laws, or God’s decrees about the ways in which created things should behave, are written into the natures of these creatures. God not only decided how creatures should act, but also gave them natures and natural powers from which these actions follow. To understand the regularities and events in nature, we do not need to look beyond the natures of creatures. This, Leibniz claims, is much more worthy of a perfect God than the occasionalist world, in which natural events are not internally intelligible.

How, then, does Leibniz explain the correspondence between mental and bodily states if he denies that there is genuine causal interaction among finite things and also denies that God brings about the correspondence by constantly intervening? Consider again the example in which I decide to get a drink from the fridge and my body executes that decision. It may seem that unless there is a fairly direct link between my decision and the action—either a link supplied by God’s intervention, or by the power of my mind to cause bodily motion—it would be an enormous coincidence that my body carries out my decision. Yet, Leibniz thinks there is a third option, which he calls ‘pre-established harmony.’ On this view, God created my body and my mind in such a way that they naturally, but without any direct causal links, correspond to one another. God knew, before he created my body, that I would decide to get a cold drink, and hence made my body in such a way that it will, in virtue of its own nature, walk to the fridge and get a bottle of water right after my mind makes that decision.

In one text, Leibniz provides a helpful analogy for his doctrine of pre-established harmony. Imagine two pendulum clocks that are in perfect agreement for a long period of time. There are three ways to ensure this kind of correspondence between them: (a) establishing a causal link, such as a connection between the pendulums of these clocks, (b) asking a person constantly to synchronize the two clocks, and (c) designing and constructing these clocks so perfectly that they will remain perfectly synchronized without any causal links or adjustments (see Ariew and Garber, pp. 147-148). Option (c), Leibniz contends, is superior to the other two options, and it is in this way that God ensures that the states of my mind correspond to the states of my body, or in fact, that the perceptions of any created substance harmonize with the perceptions of any other. The world is arranged and designed so perfectly that events in one substance correspond to events in another substance even though they do not causally interact, and even though God does not intervene to adjust one to the other. Because of his infinite wisdom and foreknowledge, God was able to pre-establish this mutual correspondence or harmony when he created the world, analogously to the way a skilled clockmaker can construct two clocks that perfectly correspond to one another for a period of time.

5. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources in English Translation

- Ariew, Roger and Daniel Garber, eds. Philosophical Essays. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989.

- Contains translations of many of Leibniz’s most important shorter writings such as the Monadology, the Principles of Nature and Grace, the Discourse on Metaphysics, and excerpts from Leibniz’s correspondence, to name just a few.

- Ariew, Roger, ed. Correspondence [between Leibniz and Clarke]. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2000.

- A translation of Leibniz’s correspondence with Samuel Clarke, which touches on many important topics in metaphysics and philosophy of mind.

- Francks, Richard and Roger S. Woolhouse, eds. Leibniz’s ‘New System’ and Associated Contemporary Texts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Contains English translations of additional short texts.

- Francks, Richard and Roger S. Woolhouse, eds. Philosophical Texts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Contains English translations of additional short texts.

- Huggard, E. M., ed. Theodicy: Essays on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil. La Salle: Open Court, 1985.

- Translation of the only philosophical monograph Leibniz published in his lifetime, which contains many important discussions of free will.

- Lodge, Paul, ed. The Leibniz–De Volder Correspondence: With Selections from the Correspondence between Leibniz and Johann Bernoulli. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

- An edition, with English translations, of Leibniz’s correspondence with De Volder, which is a very important source of information about Leibniz’s mature metaphysics.

- Loemker, Leroy E., ed. Philosophical Papers and Letters. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1970.

- Contains English translations of additional short texts.

- Look, Brandon and Donald Rutherford, eds. The Leibniz–Des Bosses Correspondence. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- An edition, with English translations, of Leibniz’s correspondence with Des Bosses, which is another important source of information about Leibniz’s mature metaphysics.

- Parkinson, George Henry Radcliffe and Mary Morris, eds. Philosophical Writings. London: Everyman, 1973.

- Contains English translations of additional short texts.

- Remnant, Peter and Jonathan Francis Bennett, eds. New Essays on Human Understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Translation of Leibniz’s section-by-section response to Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, written in the form of a dialogue between the two fictional characters Philalethes and Theophilus, who represent Locke’s and Leibniz’s views, respectively.

- Rescher, Nicholas, ed. G.W. Leibniz’s Monadology: An Edition for Students. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991.

- An edition, with English translation, of the Monadology, with commentary and a useful collection of parallel passages from other Leibniz texts.

- Strickland, Lloyd H., ed. The Shorter Leibniz Texts: A Collection of New Translations. London: Continuum, 2006.

- Contains English translations of additional short texts.

b. Secondary Sources

- Adams, Robert Merrihew. Leibniz: Determinist, Theist, Idealist. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- One of the most influential and rigorous works on Leibniz’s metaphysics.

- Borst, Clive. “Leibniz and the Compatibilist Account of Free Will.” Studia Leibnitiana 24.1 (1992): 49-58.

- About Leibniz’s views on free will.

- Brandom, Robert. “Leibniz and Degrees of Perception.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 19 (1981): 447-79.

- About Leibniz’s views on perception and perceptual distinctness.

- Davidson, Jack. “Imitators of God: Leibniz on Human Freedom.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 36.3 (1998): 387-412.

- Another helpful article about Leibniz’s views on free will and on the ways in which human freedom resembles divine freedom.

- Davidson, Jack. “Leibniz on Free Will.” The Continuum Companion to Leibniz. Ed. Brandon Look. London: Continuum, 2011. 208-222.

- Accessible general introduction to Leibniz’s views on freedom of the will.

- Duncan, Stewart. “Leibniz’s Mill Argument Against Materialism.” Philosophical Quarterly 62.247 (2011): 250-72.

- Helpful discussion of Leibniz’s mill argument.

- Garber, Daniel. Leibniz: Body, Substance, Monad. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- A thorough study of the development of Leibniz’s metaphysical views.

- Gennaro, Rocco J. “Leibniz on Consciousness and Self-Consciousness.” New Essays on the Rationalists. Eds. Rocco J. Gennaro and C. Huenemann. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. 353-371.

- Discusses Leibniz’s views on consciousness and highlights the advantages of reading Leibniz as endorsing a higher-order thought theory of consciousness.

- Jolley, Nicholas. Leibniz. London; New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Good general introduction to Leibniz’s philosophy; includes chapters on the mind and freedom.

- Jorgensen, Larry M. “Leibniz on Memory and Consciousness.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 19.5 (2011a): 887-916.

- Elaborates on Jorgensen (2009) and discusses the role of memory in Leibniz’s theory of consciousness.

- Jorgensen, Larry M. “Mind the Gap: Reflection and Consciousness in Leibniz.” Studia Leibnitiana 43.2 (2011b): 179-95.

- About Leibniz’s account of reflection and reasoning.

- Jorgensen, Larry M. “The Principle of Continuity and Leibniz’s Theory of Consciousness.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 47.2 (2009): 223-48.

- Argues against ascribing a higher-order theory of consciousness to Leibniz.

- Kulstad, Mark. Leibniz on Apperception, Consciousness, and Reflection. Munich: Philosophia, 1991.

- Influential, meticulous study of Leibniz’s views on consciousness.

- Kulstad, Mark. “Leibniz, Animals, and Apperception.” Studia Leibnitiana 13 (1981): 25-60.

- A shorter discussion of some of the issues in Kulstad (1991).

- Lodge, Paul, and Marc E. Bobro. “Stepping Back Inside Leibniz’s Mill.” The Monist 81.4 (1998): 553-72.

- Discusses Leibniz’s mill argument.

- Lodge, Paul. “Leibniz’s Mill Argument Against Mechanical Materialism Revisited.” Ergo (2014).

- Further discussion of Leibniz’s mill argument.

- McRae, Robert. Leibniz: Perception, Apperception, and Thought. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976.

- An important and still helpful, even if somewhat dated, study of Leibniz’s philosophy of mind.

- Murray, Michael J. “Spontaneity and Freedom in Leibniz.” Leibniz: Nature and Freedom. Eds. Donald Rutherford and Jan A. Cover. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. 194-216.

- Discusses Leibniz’s views on free will and self-determination, or spontaneity.

- Phemister, Pauline. “Leibniz, Freedom of Will and Rationality.” Studia Leibnitiana 26.1 (1991): 25-39.

- Explores the connections between rationality and freedom in Leibniz.

- Rozemond, Marleen. “Leibniz on the Union of Body and Soul.” Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 79.2 (1997): 150-78.

- About the mind-body problem and pre-established harmony in Leibniz.

- Rozemond, Marleen. “Mills Can’t Think: Leibniz’s Approach to the Mind-Body Problem.” Res Philosophica 91.1 (2014): 1-28.

- Another helpful discussion of the mill argument.

- Savile, Anthony. Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Leibniz and the Monadology. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Very accessible introduction to Leibniz’s Monadology.

- Simmons, Alison. “Changing the Cartesian Mind: Leibniz on Sensation, Representation and Consciousness.” The Philosophical Review 110.1 (2001): 31-75.

- Insightful discussion of the ways in which Leibniz’s philosophy of mind differs from the Cartesian view; also argues that Leibnizian consciousness consists in higher-order perceptions.

- Sotnak, Eric. “The Range of Leibnizian Compatibilism.” New Essays on the Rationalists. Eds. Rocco J. Gennaro and C. Huenemann. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. 200-223.

- About Leibniz’s theory of freedom.

- Swoyer, Chris. “Leibnizian Expression.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 33 (1995): 65-99.

- About Leibnizian perception.

- Wilson, Margaret Dauler. “Confused Vs. Distinct Perception in Leibniz: Consciousness, Representation, and God’s Mind.” Ideas and Mechanism: Essays on Early Modern Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999. 336-352.

- About Leibnizian perception as well as perceptual distinctness.

Author Information

Julia Jorati

Email: jorati.1@osu.edu

The Ohio State University

U. S. A.