Thomas Aquinas (1224/6—1274)

St. Thomas Aquinas was a Dominican priest and Scriptural theologian. He took seriously the medieval maxim that “grace perfects and builds on nature; it does not set it aside or destroy it.” Therefore, insofar as Thomas thought about philosophy as the discipline that investigates what we can know naturally about God and human beings, he thought that good Scriptural theology, since it treats those same topics, presupposes good philosophical analysis and argumentation. Although Thomas authored some works of pure philosophy, most of his philosophizing is found in the context of his doing Scriptural theology. Indeed, one finds Thomas engaging in the work of philosophy even in his Biblical commentaries and sermons.

St. Thomas Aquinas was a Dominican priest and Scriptural theologian. He took seriously the medieval maxim that “grace perfects and builds on nature; it does not set it aside or destroy it.” Therefore, insofar as Thomas thought about philosophy as the discipline that investigates what we can know naturally about God and human beings, he thought that good Scriptural theology, since it treats those same topics, presupposes good philosophical analysis and argumentation. Although Thomas authored some works of pure philosophy, most of his philosophizing is found in the context of his doing Scriptural theology. Indeed, one finds Thomas engaging in the work of philosophy even in his Biblical commentaries and sermons.

Within his large body of work, Thomas treats most of the major sub-disciplines of philosophy, including logic, philosophy of nature, metaphysics, epistemology, philosophical psychology, philosophy of mind, philosophical theology, the philosophy of language, ethics, and political philosophy. As far as his philosophy is concerned, Thomas is perhaps most famous for his so-called five ways of attempting to demonstrate the existence of God. These five short arguments constitute only an introduction to a rigorous project in natural theology—theology that is properly philosophical and so does not make use of appeals to religious authority—that runs through thousands of tightly argued pages. Thomas also offers one of the earliest systematic discussions of the nature and kinds of law, including a famous treatment of natural law. Despite his interest in law, Thomas’ writings on ethical theory are actually virtue-centered and include extended discussions of the relevance of happiness, pleasure, the passions, habit, and the faculty of will for the moral life, as well as detailed treatments of each one of the theological, intellectual, and cardinal virtues. Arguably, Thomas’ most influential contribution to theology and philosophy, however, is his model for the correct relationship between these two disciplines, a model which has it that neither theology nor philosophy is reduced one to the other, where each of these two disciplines is allowed its own proper scope, and each discipline is allowed to perfect the other, if not in content, then at least by inspiring those who practice that discipline to reach ever new intellectual heights.

In his lifetime, Thomas’ expert opinion on theological and philosophical topics was sought by many, including at different times a king, a pope, and a countess. It is fair to say that, as a theologian, Thomas is one of the most important in the history of Western civilization, given the extent of his influence on the development of Roman Catholic theology since the 14th century. However, it also seems right to say—if only from the sheer influence of his work on countless philosophers and intellectuals in every century since the 13th, as well as on persons in countries as culturally diverse as Argentina, Canada, England, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Poland, Spain, and the United States—that, globally, Thomas is one of the 10 most influential philosophers in the Western philosophical tradition.

Table of Contents

- Life and Works

- Life

- Works

- Faith and Reason

- Philosophy of Language: Analogy

- Epistemology

- The Nature of Knowledge and Science

- The Extension of Science

- The Four Causes

- The Efficient Cause

- The Material Cause

- The Formal Cause

- The Final Cause

- The Sources of Knowledge: Thomas’ Philosophical Psychology

- Metaphysics

- On Metaphysics as a Science

- On What There Is: Metaphysics as the Science of Being qua Being

- Natural Theology

- Some Methodological Considerations

- The Way of Causation: On Demonstrating the Existence of God

- The Way of Negation: What God is Not

- God is Not Composed of Parts

- God is Not Changeable

- God is Not in Time

- The Way of Excellence: Naming God in and of Himself

- Philosophical Anthropology: The Nature of Human Beings

- Ethics

- The End or Goal of Human Life: Happiness

- Morally Virtuous Action as the Way to Happiness

- Morally Virtuous Action as Pleasurable

- Morally Virtuous Action as Perfectly Voluntary and the Result of Deliberate Choice

- Morally Virtuous Action as Morally Good Action

- Morally Virtuous Action as Arising from Moral Virtue

- Human Virtues as Perfections of Characteristically Human Powers

- Infused Virtues

- Human Virtues

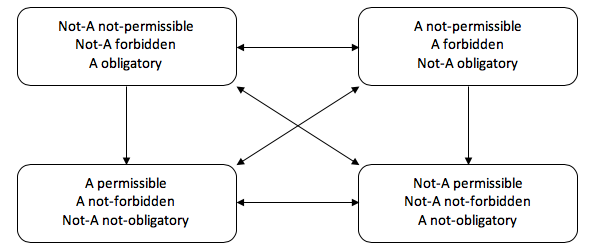

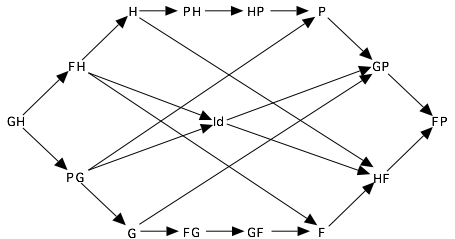

- The Logical Relations between the Human Virtues

- Moral Knowledge

- The Proximate and Ultimate Standards of Moral Truth

- Political Philosophy

- Law

- The Nature of Law

- The Different Kinds of Law

- The Eternal Law

- The Natural Law

- The Divine Law

- Human Law and its Relation to Natural Law

- Authority: Thomas’ Anti-Anarchism

- The Best Form of Government

- References and Further Reading

- Thomas’ Works

- Secondary Sources and Works Cited

- Bibliographies and Biographies

1. Life and Works

a. Life

St. Thomas Aquinas was born sometime between 1224 and 1226 in Roccasecca, Italy, near Naples. Thomas’ family was fairly well-to-do, owning a castle that had been in the Aquino family for over a century. One of nine children, Thomas was the youngest of four boys, and, given the customs of the time, his parents considered him destined for a religious vocation.

In his early years, from approximately 5 to 15 years of age, Thomas lived and served at the nearby Benedictine abbey of Monte Cassino, founded by St. Benedict of Nursia himself in the 6th century. It is here that Thomas received his early education. Thomas’ parents probably had great political plans for him, envisioning that one day he would become abbot of Monte Cassino, a position that, at the time, would have brought even greater political power to the Aquino family.

Thomas began his theological studies at the University of Naples in the fall of 1239. In the 13th century, training in theology at the medieval university started with additional study of the seven liberal arts, namely, the three subjects of the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and the four subjects of the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy), as well study in philosophy. As part of his philosophical studies at Naples, Thomas was reading in translation the newly discovered writings of Aristotle, perhaps introduced to him by Peter of Ireland. Although Aristotle’s Categories and On Interpretation (with Porphyry’s Isagoge, known as the ‘old logic’) constituted a part of early medieval education, and the remaining works in Aristotle’s Organon, namely, Prior Analytics, Posterior Analytics, Topics, and Sophismata (together known as the ‘new logic’) were known in Europe as early as the middle of the 12th century, most of Aristotle’s corpus had been lost to the Latin West for nearly a millennium. By contrast, Arab philosophers such as Ibn Sina or Avicenna (c. 980-1087) and Ibn Rushd or Averroes (1126-1198) not only had access to works such as Aristotle’s De Anima, Nicomachean Ethics, Physics, and Metaphyiscs, they produced sophisticated commentaries on those works. The Latin West’s increased contact with the Arabic world in the 12th and 13th centuries led to the gradual introduction of these lost Aristotelian works—as well as the writings of the Arabic commentaries mentioned above—into medieval European universities such as Naples. Philosophers such as Peter of Ireland had not seen anything like these Aristotelian works before; they were capacious and methodical but never strayed far from common sense. However, there was controversy too, since Aristotle seemed to teach things that contradicted the Christian faith, most notably that God was not provident over human affairs, that the universe had always existed, and that the human soul was mortal. Thomas would later try to show that such theses either represented misinterpretations of Aristotle’s works or else were founded on probabilistic rather than demonstrative arguments and so could be rejected in light of the surer teaching of the Catholic faith.

It was in the midst of his university studies at Naples that Thomas was stirred to join a new (and not altogether uncontroversial) religious order known as the Order of Preachers or the Dominicans, after their founder, St. Dominic de Guzman (c. 1170-1221), an order which placed an emphasis on preaching and teaching. Although Thomas received the Dominican habit in April of 1244, Thomas’ parents were none too pleased with his decision to join this new evangelical movement. In order to talk some sense into him, Thomas’ mother sent his brothers to bring him to the family castle sometime in late 1244 or early 1245. Back at the family compound, Thomas continued in his resolve to remain with the Dominicans. Having resisted his family’s wishes, he was placed under house arrest. A famous story has it that one day his family members sent a prostitute up to the room where Thomas was being held prisoner. Apparently, they were thinking that Thomas would, like any typical young man, satisfy the desires of his flesh and thereby “come back down to earth” and see to his familial duties. Instead, Thomas supposedly chased the prostitute out of the room with a hot poker, and as the door slammed shut behind her, traced a black cross on the door. Eventually, Thomas’ mother relented and he returned to the Dominicans in the fall of 1245. Despite these family troubles, Thomas remained dedicated to his family for the rest of his life, sometimes staying in family castles during his many travels and even acting late in his life as executor of his brother-in-law’s will.

Recognizing his talent early on, the Dominican authorities sent Thomas to study with St. Albert the Great at the University of Paris for three years, from 1245-1248. Thomas made such an impression on Albert that, having been transferred to the University of Cologne, Albert took Thomas along with him as his personal assistant.

From 1252-1256, Thomas was back at the University of Paris, teaching as a Bachelor of the Sentences. We might think of Thomas’ position at Paris at this time as roughly equivalent to an advanced graduate student teaching a class of his or her own. In addition to his teaching duties, Thomas was also required, in accord with university standards of the time, to work on a commentary on Peter the Lombard’s Sentences. We might think of Thomas’ commentary on the Sentences as roughly equivalent to his doctoral dissertation in theology.

At 32 years of age (1256), Thomas was teaching at the University of Paris as a Master of Theology, the medieval equivalent of a university professorship. After teaching at Paris for three years, the Dominicans moved Thomas back to Italy, where he taught in Naples (from 1259-1261), Orvietto (1261-1265), and Rome (1265-1268). It was during this period, perhaps in Rome, that Thomas began work on his magisterial Summa theologiae.

Thomas was ordered by his superiors to return to the University of Paris in 1268, perhaps to defend the mendicant way of life of the Dominicans and their presence at the university. (Like the Franciscans, the Dominicans depended upon the charity of others in order to continue their work and survive. This sometimes meant they had to beg for their food. In doing so, the members of the mendicant orders consciously saw themselves as living after the pattern of Jesus Christ, who, as the Gospels depict, also depended upon the charity of others for things to eat and places to rest during his public ministry.) Thomas ended up teaching at the University of Paris again as a regent Master from 1268-1272. While he was at the University of Paris, Thomas also famously disputed with philosophers who contended on Aristotelian grounds—wrongly in Thomas’ view—that all human beings shared one intellect, a doctrine that Thomas argued was incompatible with personal immortality and moral responsibility, not to mention our experience of ourselves as individual knowers.

In 1272, the Dominicans moved Thomas back to Naples, where he taught for a year. In the middle of composing his treatise on the sacraments for the Summa theologiae around December of 1273, Thomas had a particularly powerful religious experience. After the experience, despite constant urging from his confessor and assistant Reginald of Piperno, Thomas refused any longer to write. Called to be a theological consultant at the Second Council of Lyon, Thomas died in Fossanova, Italy, on March 7, 1274, while making his way to the council.

Canonized in 1323, Thomas was later proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by Pope St. Pius V in 1567. In 1879, Pope Leo XIII published the encyclical Aeterni Patris, which, among other things, holds up Thomas as the supreme model of the Christian philosopher. Through his voluminous, insightful, and tightly argued writings, Thomas continues to this day to attract numerous intellectual disciples, not only among Catholics, but among Protestants and non-Christians as well.

b. Works

Thomas is famous for being extremely productive as an author in his relatively short life. For example, he authored four encyclopedic theological works, commented on all of the major works of Aristotle, authored commentaries on all of St. Paul’s letters in the New Testament, and put together a verse by verse collection of exegetical comments by the Church Fathers on all four Gospels called the Catena aurea. Such examples constitute only the beginning of a comprehensive list of Thomas’ works. His literary output is as diverse as it is large. Thomas’ body of work can be usefully split up into nine different literary genera: (1) theological syntheses, for example, Summa theologiae and Summa contra gentiles; (2) commentaries on important philosophical works, for example, Commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Commentary on Pseudo-Dionysius’ De divinis nominibus; (3) Biblical commentaries, for example, Literal Commentary on Job and Commentary and Lectures on the Epistles of Paul the Apostle; (4) disputed questions, for example, On Evil and On Truth; (5) works of religious devotion, for example, the Liturgy of Corpus Christi and the hymn Adoro te devote; (6) academic sermons, for example, Beata gens, sermon for All Saints; (7) short philosophical treatises, for example, On Being and Essence and On the Principles of Nature; (8) polemical works, for example, On the Eternity of the World against Murmurers, and (9) letters in answer to requests for an expert opinion, for example, On Kingship. For present purposes, this article focuses on the first four of these literary genera. This should be enough to demonstrate the capaciousness of Thomas’ thought.

Thomas’ most famous works are his so-called theological syntheses. Thomas composed four of these during his lifetime: his commentary on Peter Lombard’s Sentences, Summa contra gentiles, Compendium theologiae, and Summa theologiae. Although each of these works was composed for different reasons, they are nonetheless similar insofar as each of them attempts to communicate clearly and defend the substance of the Catholic faith in a manner that can be understood by someone who has the requisite education, that is, training in the liberal arts and Aristotle’s philosophy of science. Although Thomas aims at both clarity and brevity in the works, because Thomas also aims to speak about all the issues integral to the teaching the Catholic faith, the works are quite long (for example, Summa theologiae, although unfinished, numbers 2,592 pages in the English translation of the Fathers of the English Dominican Province).

Thomas’ Summa contra gentiles (SCG), his second great theological synthesis, is split up into four books: book I treats God; book II treats creatures; book III treats divine providence; book IV treats matters pertaining to salvation. Whereas the last book treats subjects the truth of which cannot be demonstrated philosophically, the first three books are intended by Thomas as what we might call works of natural theology, that is, theology that from first to last does not defend its conclusions by citing religious authorities but rather contains only arguments that begin from premises that are or can be made evident to human reason apart from divine revelation and end by drawing logically valid conclusions from such premises. SCG is thus Thomas’ longest and most ambitious attempt at doing what he is probably most famous for—arguing philosophically for various theses concerning the existence of God, the nature of God, and the nature of creatures insofar as they are creatures of God. Although Thomas cites Scripture in these first three books in SCG, such citations always come on the heels of Thomas’ attempt to establish a point philosophically. In citing Scripture in the SCG, Thomas thus aims to demonstrate that faith and reason are not in conflict, that those conclusions reached by way of philosophy coincide with the teachings of Scripture.

Summa theologiae (ST) is Thomas’ most well-known work, and rightly so, for it displays all of Thomas’ intellectual virtues: the integration of a strong faith with great learning; acute organization of thought; judicious use of a wide range of sources, including pagan and other non-Christian sources; an awareness of the complexity of language; linguistic economy; and rigorous argumentation. However, ST is not a piece of scholarship as we often think of scholarship in the early 21st century, that is, a professor showing forth everything that she knows about a subject. Rather, it is the work of a gifted teacher, one intended by its author, as Thomas himself makes clear in the prologue, to aid the spiritual and intellectual formation of his students. It was once thought that Thomas meant ST to replace Lombard’s Sentences as a university textbook in theology, which, incidentally, did begin to happen as early as one hundred and fifty years after Thomas’ death. Recent scholarship has suggested that Thomas rather composed the work for Dominican students preparing for priestly ministry. This thesis is consistent with what Thomas actually does in ST, which may surprise people who have not examined the work as a whole.

What of the method and content of ST? Like Lombard’s Sentences, Thomas’ ST is organized according to the neo-Platonic schema of exit from and return to God. This is no accident. Thomas thinks it is fitting that divine science should imitate reality not only in content but in form. ST is split into three parts. Part one (often abbreviated “Ia.”) treats God and the nature of spiritual creatures, that is, angels and human beings. Part two treats the return of human beings to God by way of their exercising the virtues, knowing and acting in accord with law, and the reception of divine grace. Given the Fall of human beings, part three (often abbreviated “IIIa.”) treats the means by which human beings come to embody the virtues, know the law, and receive grace: (a) the Incarnation, life, passion, death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ, as well as (b) the manner in which Christ’s life and work is made efficacious for human beings, through the sacraments and life of the Church.

Of the three parts of ST, the second part on ethical matters is by far the longest, which is one reason recent scholarship has suggested that Thomas’ interest in composing ST is more practical than theoretical. We might think of ST as a work in Christian ethics, designed specifically to teach those Dominican priests whose primary duties were preaching and hearing confessions. In fact, part two of ST is so long that Thomas splits it into two parts, where the length of each one of these parts is approximately 600 pages in English translation. The first part of the second part is often abbreviated “IaIIae”; the second part of the second part is often abbreviated “IIaIIae.”

The fundamental unit of ST is known as the article. It is in the article that Thomas works through some particular theological or philosophical issue in considerable detail, although not in too much detail. (Recall Thomas is training priests for ministry, not scholars. For Thomas’ most detailed discussions of a topic, readers should turn to his treatment in his disputed questions, his commentary on the Sentences, SCG, and the Biblical commentaries.) Thomas treats a very specific “yes” or “no” question in each article in accord with the method of the medieval disputatio. That is to say, each article within the ST is, as it were, a mini-dialogue. Each article within ST has five parts. First, Thomas raises a very specific question, for example, “whether law needs to be promulgated.” Second, Thomas entertains some objections to the position that he himself defends on the specific question raised in the article. In other words, Thomas is here fielding objections to his own considered position. Third, Thomas cites some authority (in a section that begins, on the contrary) that gives the reader the strong impression that the position defended in the objections is, in fact, untenable. Oftentimes the authority Thomas cites is a passage from the Old or New Testament; otherwise, it is some authoritative interpreter of Scripture or science such as St. Augustine or Aristotle, respectively. It should be noted the authority cited is in no way, shape, or form Thomas’ final word on the subject at hand. Thomas is well aware that authorities need to be interpreted. Fourth, Thomas develops his own position on the specific topic addressed in the article. This part of the article is oftentimes referred to as the body or the respondeo, literally, I respond. Here, Thomas offers arguments in defense of his own considered position on the matter at issue. Sometimes Thomas examines various possible positions on the question at hand, showing why some are untenable whereas others are defensible. At other times, Thomas shows that much of the problem is terminological; if we appreciate the various senses of a term crucial to the science in question, we can show that authorities that seem to be in conflict are simply using an expression with different intended meanings and so do not disagree after all. Fifth, Thomas returns to the objections and answers each of them in light of the work he has done in the body of the article. It should be noted that Thomas often adds interesting details in these answers to the objections to the position he has defended in the body of the article.

In addition to his theological syntheses, Thomas composed numerous commentaries on the works of Aristotle and other neo-Platonic philosophers. For example, Thomas commented on all of Aristotle’s major works, including Metaphysics, Physics, De Anima, and Nichomachean Ethics. These are line-by-line commentaries, and contemporary Aristotle scholars have remarked on their insightfulness, despite the fact that Thomas himself did not know Greek (although he was working from Latin translations of Greek editions of Aristotle’s text). The focus in Thomas’ commentaries is certainly explaining the mind of Aristotle. That being said, given that Thomas sometimes corrects Aristotle in these works (see, for example, his commentary on Physics, book 8, chapter 1), it seems right to say that Thomas’ commentaries on Aristotle are usefully consulted to elucidate Thomas’ own views on philosophical topics as well.

Thomas is often spoken of as an Aristotelian. This is particularly so when speaking of Thomas’ philosophy of language, metaphysics of material objects, and philosophy of science. When it comes to Thomas’ metaphysics and moral philosophy, though, Thomas is equally influenced by the neo-Platonism of Church Fathers and other classical thinkers such as St. Augustine of Hippo, Pope St. Gregory the Great, Proclus, and the Pseudo-Dionysius. One way to see the importance of neo-Platonic thought for Thomas’ own thinking is by noting the fact that Thomas authored commentaries on a number of important neo-Platonic works. These include commentaries on Boethius’ On the Hebdomads, Boethius’ De trinitate, Pseudo-Dionysius’ On the Divine Names, and the anonymous Book of Causes. (The last work Thomas correctly identified as the work of an Arab philosopher who borrowed greatly from Proclus’ Elementatio Theologica and the work of Dionysius; previously it had been thought to be a work of Aristotle’s).

Although Thomas commented on a number of philosophical works, Thomas probably saw his commentaries on Scripture as his most important. (Thomas commented on Job, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Psalms 1-51 (this commentary was interrupted by his death), Matthew, John, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, and Hebrews. Thomas also composed a running gloss on the four gospels, the Catena aurea, which consists of a collection of what various Church Fathers have to say about each verse in each of the four gospels.) Thomas understood himself to be, first and foremost, a Catholic Christian theologian. Indeed, theology professors at the University of Paris in Thomas’ time were known as Masters of the Sacred Page. In addition, Thomas was a member of the Dominican order, and the Dominicans have a special regard for teaching the meaning of Scripture.

A reader might wonder why one would mention Thomas’ commentaries on Scripture in an article focused on his contributions to the discipline of philosophy. It is important to mention Thomas’ Scripture commentaries since Thomas often does his philosophizing in the midst of doing theology, and this is no less true in his commentaries on Scripture. To give just one example of the importance of Thomas’ Scripture commentaries for understanding a philosophical topic in his thought, he has interesting things to say about the communal nature of perfect happiness in his commentaries on St. Paul’s letters to the Corinthians and to the Ephesians. A reader who focused merely on Thomas’ treatment of perfect happiness in, for example, the Summa theologiae, would get an incomplete picture of his views on human happiness.

Where talk of Thomas’ philosophy is concerned, there is a final literary genus worth mentioning, the so-called disputed question. Like ST, the articles in Thomas’ disputed questions are organized according to the method of the medieval disputatio. However, whereas a typical article in ST fields three or four objections, it is not uncommon for an article in a disputed question to field 20 objections to the position the master wants to defend. Consider, for example, the question of whether there is power in God. Whereas the article in ST that treats this question fields four objections, the corresponding article in Thomas’ Disputed Questions on the Power of God fields 18 objections. Nonetheless, it would be a mistake to think that Thomas’ disputed questions necessarily represent his most mature discussions of a topic. Although the disputed questions can be regarded as Thomas’ most detailed treatments of a subject, he sometimes changed his mind about issues over the course of his writing career, and the disputed questions do not necessarily represent his last word on a given subject.

2. Faith and Reason

Thomas’ views on the relationship between faith and reason can be contrasted with a number of contemporary views. Consider first an influential position we can label evidentialism. For our purposes, the advocate of evidentialism believes that one should proportion the strength of one’s belief B to the amount of evidence one has for the truth of B, where evidence for a belief is construed either (a) as that belief’s correspondence with a proposition that is self-evident, indubitable, or immediately evident from sense experience, or (b) as that belief’s being supported by a good argument, where such an argument begins from premises that are self-evident, indubitable, or immediately evident from sense experience (see Plantinga [2000, pp. 67-79] and Rota [2012]). Evidentialism, so construed, is incompatible with a traditional religious view that Thomas holds about divine faith: if Susan has divine faith that p, then Susan has faith that p as a gift from God, and Susan reasonably believes that p with a strong conviction, not on the basis of Susan’s personally understanding why p is true, but on the basis of Susan’s reasonably believing that God has divinely revealed that p is true. In other words, divine faith is a kind of certain knowledge by way of testimony for Thomas.

Fideism is another position with which we can contrast Thomas’ views on faith and reason. For our purposes, consider fideism to be the view that states that faith is the only way to apprehend truths about God. Put negatively, the fideist thinks that human reason is incapable of demonstrating truths about God philosophically.

Finally, consider the position on faith and reason known as separatism. According to separatism, philosophy and natural science, on the one hand, and revealed theology, on the other, are incommensurate activities or habits. Any talk of conflict between faith and reason always involves some sort of confusion about the nature of faith, philosophy, or science.

In contrast to the views mentioned above, Thomas not only sees a significant role for both faith and reason in the best kind of human life (contra evidentialism), but he thinks reason apart from faith can discern some truths about God (contra fideism), as epitomized by the work of a pagan philosopher such as Aristotle (see, for example, SCG I, chapter 3). Thomas also recognizes that revealed theology and philosophy are concerned with some of the same topics (contra separatism). Although treating some of the same topics, Thomas thinks it is not possible in principle for there to be a real and significant conflict between the truths discovered by divine faith and theology on the one hand and the truths discerned by reason and philosophy on the other. In fact, Thomas thinks it is a special part of the theologian’s task to explain just why any perceived conflicts between faith and reason are merely apparent and not real and significant conflicts (see, for example, ST Ia. q. 1, a. 8). Indeed, showing that faith and reason are compatible is one of the things Thomas attempts to do in his own works of theology. A diverse group of subsequent religious thinkers have looked to Thomas’ modeling the marriage of faith and reason as one of his most important contributions.

One place where Thomas discusses the relationship between faith and reason is SCG, book I, chapters 3-9. Thomas notes there that there are two kinds of truths about God: those truths that can be apprehended by reason apart from divine revelation, for example, that God exists and that there is one God (in the Summa theologiae, Thomas calls such truths about God the preambles to the faith) and those truths about God the apprehension of which requires a gift of divine grace, for example, the doctrine of the Trinity (Thomas calls these the articles of faith). Although the truth of the preambles to the faith can be apprehended without faith, Thomas thinks human beings are not rationally required to do so. In fact, Thomas argues that three awkward consequences would follow if God required that all human beings need to apprehend the preambles to the faith by way of philosophical argumentation.

First, very few people would come to know truths about God and, since human flourishing requires certain knowledge of God, God wants to be known by as many people as possible. Not everyone has the native intelligence to do the kind of work in philosophy required to understand an argument for the existence of God. Among those who have the requisite intelligence for such work, many do not have the time it takes to apprehend such truths by philosophy, being engaged as they are in other important tasks such as taking care of children, manual labor, feeding the poor, and so forth. Finally, among those who have the natural intelligence and time required for serious philosophical work, many do not have the passion for philosophy that is also required to arrive at an understanding of the arguments for the existence of God.

Second, of the very few who could come to know truths about God philosophically, these would apprehend these truths with anything close to certainty only late in their life, and Thomas thinks that people need to apprehend truths such as the existence of God as soon as possible. (Compare here with a child learning that it is wrong to lie; parents wisely want their children to learn this truth as soon as possible.) In order to understand why Thomas thinks that the existence of God is a truth discernible by way of philosophy only late in life, we need to appreciate his view of philosophy, metaphysics, and natural theology. Philosophy is a discipline we rightly come to only after we have gained some confidence in other disciplines such as arithmetic, grammar, and logic. Among the philosophical disciplines, metaphysics is the most difficult and presupposes competence in other philosophical disciplines such as physics (as it is practiced, for example, in Aristotle’s Physics, that is, what we might call philosophical physics, that is, reflections on the nature of change, matter, motion, and time). Finally, demonstrating the existence of God is the hardest part of metaphysics. If we are to apprehend with confidence the existence of God by way of philosophy, this will happen only after years of intense study and certainly not during childhood, when we might think that Thomas believes it is important, if not necessary, for it to happen.

Third, let us suppose Susan has the native intelligence, time, passion, and experience requisite for apprehending the existence of God philosophically and that she does, in fact, come to know that God exists by way of a philosophical argument. Thomas maintains that such an apprehension is nonetheless going to be deficient for it will not allow Susan to be totally confident that God exists, since Susan is cognizant—being the philosopher she is—that there is a real possibility she has made a mistake in her philosophical reasoning. However, the good life, for example, living like a martyr, requires that we possess an unshakeable confidence that God exists. Since God wants as many people as possible to apprehend his existence, and to do so as soon as possible and with the kind of confidence enjoyed by the Apostles, saints, and martyrs, Thomas argues that it is fitting that God divinely reveals to human beings—even to theologians who can philosophically demonstrate the existence of God—the preambles to the faith, that is, those truths that can be apprehended by human reason apart from divine faith, so that people from all walks of life can, with great confidence, believe that God exists as early in life as possible.

However, does it make sense to believe things about God that exceed the natural capacity of human reason? Thomas thinks the answer is “yes,” and he defends this answer in a number of ways. Two are mentioned here. First, Thomas thinks it sensible of God to ask human beings to believe things about God that exceed their natural capacities since to do so reinforces in human beings an important truth about God, namely, that God is such that He cannot be completely understood by way of our natural capacities. If we say we completely understand God by way of our natural capacities, then we do not understand what “God” means. Talk about God, for Thomas, requires that we recognize our limitations with respect to such a project. God’s asking us to believe things about Him that we cannot apprehend philosophically makes sense for Thomas because it alerts human beings to the fact that we cannot know God in the same way we know the objects of other sciences.

Thomas also notes that believing things about God by faith perfects the soul in a manner that nothing else can. Here Thomas draws on the testimony of Aristotle, who thinks that even a little knowledge of the highest and most beautiful things perfects the soul more than a complete knowledge of earthly things. Although we cannot understand the things of God that we apprehend by faith in this life, even a slim knowledge of God greatly perfects the soul. Just as a bit of real knowledge of human beings is better for Susan’s soul than Susan’s knowing everything there is to know about carpenter ants, Susan’s possessing knowledge about God by faith is better for Susan’s soul than Susan’s knowing scientifically everything there is to know about the cosmos.

Still, we might wonder why Thomas thinks it is reasonable to accept the Catholic faith as opposed to some other faith tradition that, like the Catholic faith, asks us to believe things that exceed the capacity of natural reason. One thing Thomas says is that some non-Catholic religious traditions ask us to believe things that are contrary to what we can know by natural reason. Thomas accepts the medieval maxim that “grace does not destroy nature or set it aside; rather grace always perfects nature.” Although the Catholic faith takes us beyond what natural reason by itself can apprehend, according to Thomas, it never contradicts what we know by way of natural reason. Therefore, any real conflicts between faith and reason in non-Catholic religious traditions give us a reason to prefer the Catholic faith to non-Catholic faith traditions.

In addition, Thomas thinks there are good—although non-demonstrative—arguments for the truth of the Catholic faith. Thomas begins with the accounts of healings, the resurrection of the dead, and miraculous changes in the heavenly bodies, as contained in the Old and New Testaments. These accounts of miracles—which Thomas takes to be historically reliable—offer confirmation of the truthfulness of the teaching of those who perform such works by the grace of God. Even more significant, thinks Thomas, is the fact that simple fishermen were transformed overnight into apostles, that is, eloquent and wise men. Thomas takes this to be a miracle that provides confirmation of the truth of the Catholic faith the apostles preached. Most powerful of all, according to Thomas, the Catholic faith spread throughout the world in the midst of great persecutions. As Thomas notes, the Catholic faith was not initially embraced because it was economically advantageous to do so; nor did it spread—as other religious traditions have—by way of the sword; in fact, people flocked to the Catholic faith—as Thomas notes, both the simple and the learned—despite the fact that it teaches things that surpass the natural capacity of the intellect and demands that people curb their desires for the pleasures of the flesh. Given human nature, Thomas thinks that such conversions were miraculous and so testify to the truth of the faith that such people came to adopt.

3. Philosophy of Language: Analogy

Any discussion of Thomas’ views concerning what something is, for example, goodness or knowledge or form, requires some stage-setting. Much of contemporary analytic philosophy and modern science operates under the assumption that any discourse D that deserves the honor of being called scientific or disciplined requires that the terms employed within D not be used equivocally. Thomas agrees, but with a very important caveat. Thomas distinguishes two different kinds of equivocation: uncontrolled (or complete) equivocation and controlled equivocation (or analogous predication). While the former is incompatible with a discourse being scientific or disciplined, according to Thomas, the latter is not. Thomas therefore distinguishes three different ways words are used: univocally, equivocally (in a sense that is complete or uncontrolled), and analogously, that is, equivocally but in a manner that is controlled. When we use a word univocally, we predicate of two things (x and y) one and the same name n, where n has precisely the same meaning when predicated of x and y. For example, think of the locutions, “the cat is an animal” and “the dog is an animal.” Here, the same word “animal” is predicated of two different things, but the meaning of “animal” is precisely the same in both instances. By contrast, when we use a word equivocally, two things (x and y) are given one and the same name n, where n has one meaning when predicated of x and a different meaning when predicated of y. For example, we use the very same word “bank” to refer to a place where we save money and that part of the land that touches the edge of a river.

Importantly, Thomas notices that some instances of equivocation are controlled, or instances of analogous predication, whereas other instances of equivocal naming are complete or uncontrolled. In a case of complete or uncontrolled equivocation, we predicate of two things (x and y) one and the same name n, where n has one meaning when predicated of x and n has a completely different meaning when predicated of y. English usage of the word “bank” is a good example of complete or uncontrolled equivocation; here the use of the same name is totally an accident of language. It is a matter of linguistic chance that “bank” has these two totally different and unrelated meanings in English.

By contrast, in a case of controlled equivocation or analogous predication, we predicate of two things (x and y) one and the same name n, where n has one meaning when predicated of x, n has a different but not unrelated meaning when predicated of y, where one of these meanings is primary whereas the other meaning derives its meaning from the primary meaning. For example, consider the manner in which we use the word “good.” We sometimes speak of “good dogs,” and sometimes we say things such as “Doug is a good man.” The meanings of “good” in these two locutions obviously differ one from another since in the first sense no moral commendation is implied where there is moral commendation implied in the latter. However, it also seems right to say that “good” is not being used in completely different and unrelated ways in these locutions. Rather, our speaking of “good dogs” derives its meaning from the primary meaning of “good” as a way to offer moral commendation of human beings. We thus use the word “good” as an analogous expression in Thomas’ sense. To take an example Aristotle uses, “healthy” is used in the primary sense in a locution such as “Joe is healthy.” We might also say “Joe’s urine is healthy,” which uses “healthy” to pick out a sign of Joe’s health (in the primary sense of that term), or “exercise is healthy,” which uses “healthy” to pick out a cause of health (again, in the primary sense).

Thomas takes analogous predication or controlled equivocation to be sufficient for good science and philosophy, assuming, of course, that the other relevant conditions for good science or philosophy are met. Although the most famous use to which Thomas puts his theory of analogous naming is his attempt to make sense of a science of God, analogous naming is relevant where many other aspects of philosophy are concerned, Thomas thinks. For example, we also use words analogously when we talk about being, knowledge, causation, and even science itself. Thomas therefore sees a significant difference between complete equivocation and controlled equivocation or analogous naming. Whereas the scientist qua scientist must avoid the former, a discipline that uses words in the latter sense can properly be understood to be scientific or disciplined.

4. Epistemology

a. The Nature of Knowledge and Science

Thomas is aware of the fact that there are different forms of knowledge. One form of knowledge that is particularly important to a 13th-century professor such as Thomas is scientific knowledge (scientia). However, Thomas recognizes that scientific knowledge itself depends upon there being non-scientific kinds of knowledge, for example, sense knowledge and knowledge of self-evident propositions (about each of which, there is more below). We can begin to get a sense of what Thomas means by scientia by way of his discussion of faith, which is a form of knowledge he often contrasts with scientia (see, for example, ST IIaIIae. q. 1, aa. 4-5; q. 2, a. 1). According to Thomas, faith and scientia are alike in being subjectively certain. If I believe that p by faith, then I am confident that p is true. It is likewise with scientific knowledge. However, the reason for one’s being confident that p differs in the cases of faith and scientia. If I know that p by way of science, then I not only have compelling reasons that p, but I understand why those reasons compel me to believe that p. In contrast to scientia, the certainty of faith that p is grounded for Thomas in a rational belief that someone else has scientia or intellectual vision with respect to p. Thus, the certainty of faith is grounded in someone else’s testimony—in the case of divine faith, the testimony of God. For Thomas, faith can and, at least for those who have the time and talent, should be supported by reasons. However, if Susan believes p by faith, Susan may see that p is true, but she does not see why p is true. Susan’s belief that p is ultimately grounded in confidence concerning some other person, for example, Jane’s epistemic competence, where Jane’s competence involves seeing why p is true, either by way of Jane’s having scientia of p, because Jane knows that p is self-evidently true, or because Jane has sense knowledge that p.

We should note that, for Thomas, scientia itself is a term that we rightly use analogously. For example, in speaking of science, we could be talking about an act of inquiry whereby we draw certain conclusions, not previously known, from things we already know, that is, starting from first principles, where these principles are themselves known by way of (reflection upon our) sense experiences, we draw out the logical implications of such principles. We can contrast science as an act of inquiry with another kind of speculative activity that Thomas calls contemplation. Both science (in the sense of engaging in an act of inquiry) and contemplation are acts of speculative intellect according to Thomas, that is, they are uses of intellect that have truth as their immediate object. (In contrast, practical uses of intellect are acts of intellect that aim at the production of something other than what is thought about, for example, thinking at the service of doing the right thing, in the right way, at the right time, and so forth, or thinking at the service of bringing about a work of art.) Thomas thinks that, whereas an act of scientific inquiry aims at discovering a truth not already known, an act of contemplation aims at enjoying a truth already known.

We can speak of science not only as an act of inquiry, but also as a particularly strong sort of argument for the truth of a proposition that Thomas calls a scientific demonstration. If a person possesses a scientific demonstration of some proposition p, then he or she understands an argument that p such that the argument is logically valid and he or she knows with certainty that the premises of the argument are true.

In addition to the senses of science mentioned above, Thomas also recognizes the Aristotelian sense of scientia as a particular kind of intellectual habit or disposition or virtue, which habit is the fruit of scientia as scientific inquiry and requires the possession of scientific demonstrations. But science in the sense of a habit is more than the fruit of inquiry and the possession of arguments. Science as a habit is a person’s possession of an organized body of knowledge of and demonstrative argumentation about some subject matter S, where possessing an organized body of knowledge of and demonstrative argumentation about some subject matter is a function of knowing (a) the basic facts about S, that is, the characteristic properties or powers of things belonging to S, as well as (b) the principles, causes, or explanations of these properties or powers of S, and (c) the logical connections between (a) and (b). For example, according to this model of science, I have a scientific knowledge of living things qua living things only if I know the basic facts about all living things, for example, that living things grow and diminish in size over time, nourish themselves, and reproduce, and I know why living things have these characteristic powers and properties. According to Thomas, a science as habit is a kind of intellectual virtue, that is, a habit of knowledge about a subject matter, acquired from experience, hard work, and discipline, where the acquisition of that habit usually involves having a teacher or teachers. A person who possesses a science s knows the right kind of starting points for thinking about s, that is, the first principles or indemonstrable truths about s, and the scientist can draw correct conclusions from these first principles. In other words, if one has a science of s, one’s knowledge of s is systematic and controlled by experience, and so one can speak about s with ease, coherence, clarity, and profundity.

Thomas notes that the first principles of a science are sometimes naturally known by the scientist, for example in the cases of arithmetic and geometry (ST Ia. q. 1, a. 2). According to Thomas, the science of sacred theology does not fit this characterization of science since the first principles of sacred theology are articles of faith and so are not known by the natural light of reason but rather by the grace of God revealing the truth of such principles to human beings. Of course, contemporary philosophers of science would not find sacred theology’s inability to fit neatly into a well-defined univocal conception of science to be a problem for the scientific status of sacred theology. Think of the demarcation problem, that is, the problem of identifying necessary and sufficient conditions for some discourse counting as science. The demarcation problem suggests that science is a term we use analogously. This is what Thomas thinks. For example, Thomas recognizes that, even among those sciences whose first premises are known to some human beings by the natural light of reason, there are some sciences (call them “the xs”) such that scientists practicing the xs, at least where knowledge of some of the first principles of the xs is concerned, depend upon the testimony of scientists in disciplines other than their own. For example, optics makes use of principles treated in geometry, and music makes use of principles treated in mathematics. If, for example, all musicians had to be experts at mathematics, most musicians would never get to practice the science of music itself. Thus, musicians take the principles and findings of mathematics as a starting point for the practice of their own science. Like optics and music, therefore, sacred theology draws on principles known by those with a higher science, in this case, the science possessed by God and the blessed (see, for example, ST Ia. q. 1, a. 2, respondeo). Unlike optics, music, and other disciplines studied at the university, the principles of sacred theology are not known by the natural light of reason. However, sacred theology is nonetheless a science, since those who possess such a science can, for example, draw logical conclusions from the articles of faith, argue that one article of faith is logically consistent with the other articles of faith, and answer objections to the articles of faith, doing all of these things systematically, clearly, and with ease by drawing on the teachings of other sciences, including philosophy (ST Ia. q. 1, a. 8).

b. The Extension of Science

Given his notion of science (whether taken as activity, demonstrative argument or intellectual virtue), we might think that Thomas understands the extension of science to be wider than what most of our contemporaries would allow. There is a sense in which this is true. Although there is certainly disagreement among our contemporaries over the scientific status of some disciplines studied at modern universities, for example, psychology and sociology, all agree that disciplines such as physics, chemistry, and biology are to be counted among the sciences. The demarcation problem notwithstanding, we tend to think of science as natural science, where a natural science constitutes a discipline that studies the natural world by way of looking for spatio-temporal patterns in that world, where “the way of looking” tends to involve controlled experiments (Artigas 2000, p. 8). Thomas would have known something of science in this sense from his teacher St. Albert the Great (c. 1206-1280). However, for Thomas, (for whom science is understood as a discipline or intellectual virtue) disciplines such as mathematics, music, philosophy, and theology count as sciences too since those who practice such disciplines can talk about the subjects studied in those disciplines in a way that is systematic, orderly, capacious, and controlled by common human experience (and, in some cases, in the light of the findings of other sciences).

On the other hand, there is a sense in which Thomas’ understanding of science is more restrictive than the contemporary notion. Thomas follows Aristotle in thinking that we know something x scientifically only if our knowledge of x is certain. That is to say, we have demonstrative knowledge of x, that is, our knowledge begins from premises that we know with certainty by way of reflection upon sense experience, for example, all animals are mortal or there cannot be more in the effect than in its cause or causes, and ends by drawing logically valid conclusions from those premises. However, it seems to be a hallmark of the modern notion of science that the claims of science are, in fact, fallible, and so, by definition, uncertain.

c. The Four Causes

No account of Thomas’ philosophy of science would be complete without mentioning the doctrine of the four causes. Following Aristotle, Thomas thinks the most capacious scientific account of a physical object or event involves mentioning its four causes, that is, its efficient, material, formal, and final causes. Of course, some things (of which we could possibly have a science of some sort) do not have four causes for Thomas. For example, immaterial substances will not have a material cause. However, Thomas thinks that material objects—whether natural or artificial—do have four causes. For example, for any material object O, O has four causes, the material cause (what O is made of), the formal cause (what O is), the final cause (what the end, goal, purpose, or function of O is), and the efficient cause (what brings—or conserves—O in(to) being). One has a scientific knowledge of O (or O’s kind) only if one knows all four causes of O or the kind to which O belongs. Here follows a more detailed account of each of the four causes as Thomas understands them.

i. The Efficient Cause

An efficient cause of x is a being that acts to bring x into existence, preserve x in existence, perfect x in existence, or otherwise bring about some feature F in x. For example, Michelangelo was the efficient cause of the David. Thomas thinks that there are different kinds of efficient causes, which kinds of efficient causes may all be at work in one and the same object or event, albeit in different ways. For example, Thomas thinks that God is the primary efficient cause of any created being, at every moment in which that created being exists. That is, if it were not for God’s timelessly and efficiently causing a creature to exist at some time t, that creature would not exist at t. God’s act of creation and conservation with respect to some creature C does not rule out that C also simultaneously has creatures as secondary efficient causes of C. This is because God and creatures are efficient causes in different and yet analogous senses. God is the primary efficient cause as creator ex nihilo, timelessly conserving the very existence of any created efficient cause at every moment that it exists, whereas creatures are secondary efficient causes in the sense that they go to work on pre-existing matter such that matter that is merely potentially F actually becomes F. For example, we might say that a sperm cell and female gamete work on one another at fertilization and thereby function as secondary efficient causes of a human being H coming into existence. To continue with this example, Thomas thinks that God, too, is at work as the primary efficient cause of H’s coming into existence, since, for example, (a) God is the creating and conserving cause of (i) any sperm cell as long as it exists, (ii) any female gamete as long as it exists, and (iii) all aspects of the environment necessary for successful fertilization. In addition, Thomas thinks (b) God is the creating and conserving cause of the existence of H itself as long as H exists.

ii. The Material Cause

Thomas thinks that “material cause” (or simply “matter”) is an expression that has a number of different but related meanings. Perhaps the most obvious sense of “matter” is what “garden-variety” objects and their “garden-variety” parts are made of. In this sense of “matter,” the material cause of an axe is some iron and some wood.

There is one sense of “matter” that is very important for an analysis of change, thinks Thomas. Matter in this sense explains why x is capable of being transformed into something that x currently is not. The material cause in this sense is the subject of change—that which explains how something can lose the property not-F and gain the property F. For example, the material cause for an accidental change is some substance. Socrates himself is the material cause of the change that consists in Socrates’ losing the property of not-standing and gaining the property of standing. Such a change is accidental since the substance we name Socrates does not in this case go out of existence in virtue of losing the property of not-standing and gaining the property of standing.

The material cause for a substantial change is what medieval interpreters of Aristotle such as Thomas call prima materia (prime or first matter). Prime matter is that cause of x that is intrinsic to x (we might say, is a part of x) that explains why x is subject to substantial change. For Thomas, substances are unified objects of the highest order. Substances, for example, living things, are thus to be directly contrasted with heaps or collections of objects, for example, a pile of garbage or an army. Thomas thinks that if substantial changes had actual substances functioning as the ultimate subjects for those substantial changes, then it would be reasonable to call into question the substantial existence of those so-called substances that are (supposedly) composed of such substances. If Socrates were composed, say, of Democritean atoms that were substances in their own right, then Socrates, at best, would be nothing more than an arrangement of atoms. He would merely be an accidental being—an accidental relation between a number of substances—instead of a substance. At worst, Socrates would not exist at all (if we think the only substances are fundamental entities such as atoms, and Socrates is not an atom). Since Thomas thinks of Socrates as a paradigm case of a substance, he thus thinks that the matter of a substantial change must be something that is in and of itself not actually a substance but is merely the ultimate material cause of some substance. Thomas calls this ultimate material cause of a substance that can undergo substantial change prime matter. For example, consider that a bear eats a bug at t, so that the bug exists in space s, that is, the bear’s stomach, at t. Some prime matter therefore is configured by the substantial form of a bug in s at t such that there is a bug in s at t. At time t+1, when the bug dies in the bear’s stomach, the prime matter in s loses the substantial form of a bug and that prime matter comes to be configured by a myriad of substantial forms such that the bug no longer exists at t+1. What exists in s at t+1 is a collection of substances, for example, living cells arranged bug-wise, where the cells themselves will soon undergo substantial changes so that what will exist is a collection of non-living substances, for example, the kinds and numbers of atoms and molecules that compose the living cells of a living bug.

That being said, Thomas thinks prime matter never exists without being configured by some form. First of all, matter always exists under dimensions, and so this prime matter (rather than that prime matter) is configured by the accidental form of quantity, and more specifically, the accidental quantity of existing in three dimensions (see, for example, Commentary on Boethius’ De trinitate q. 4, a. 2, respondeo). In addition, it is never the case that some prime matter exists without being configured by some substantial form. For example, some quantity of prime matter m might be configured by the substantial form of an insect at t, be configured by the substantial forms of a collection of living cells at t+1 (for example, some moments after the insect has been eaten by a frog), be configured by the substantial forms of a collection of chemical compounds at t+2, and be incorporated into the body of a frog as an integral part of the frog such that it is configured by the frog’s substantial form at t+3. A portion of prime matter is always configured by a substantial form, though not necessarily this or that substantial form.

Note the theoretical significance of the view that material substances are composed of prime matter as a part. Prime matter is the material causal explanation of the fact that a material substance S’s generation and (potential) corruption are changes that are real (contra Parmenides of Elea), substantial (contra atomists such as Democritus), natural (contra those who might say that all substantial changes are miraculous), and intelligible (contra Heraclitus of Ephesus and Plato of Athens).

iii. The Formal Cause

Like the material cause of an object, the expression formal cause is said in many ways. There are at least three for Thomas. First, formal cause might mean “the nature or definition of a thing,” that is, what-it-is-to-be S. The formal cause of a primary substance x in this sense is the substance-sortal that picks out what x is most fundamentally or the definition of that substance-sortal. For example, for Socrates this would be human being, or, what-it-is-to-be-a-human being, and, given that human beings can be defined as rational animals, rational animal. Although Socrates certainly belongs to other substance-sortals, for example, animal, living thing, rational substance, and substance, such substance-sortals only count as genera to which Socrates belongs; they do not count as Socrates’ infima species, that is, the substance-sortal that picks out what Socrates is most fundamentally. Of course, Socrates can be classified in many other ways, too, for example, as a philosopher or someone who chose not to flee his Athenian prison. However, such classifications are not substantial for Thomas, but merely accidental, for Socrates need not be (or have been) a philosopher—for example, Socrates was not a philosopher when he was two years old, nor someone who chose not to flee his Athenian prison, for even Socrates might have failed to live up to his principles on a given day.

A second sense that formal cause can have for Thomas is that which is intrinsic to or inheres in x and explains that x is actually F. There are two kinds of formal cause in this sense for Thomas. First, there are accidental forms (or simply, accidents). Accidental forms inhere in a substance and explain that a substance x actually is F, where F is a feature that x can gain or lose without x’s ceasing to exist, for example, Socrates’ being tan, Socrates’ weighing 180 lbs, and so forth. Second, there are substantial forms. According to Thomas, substantial forms are particulars—each individual substance has its own individual substantial form—and the substantial form of a substance is the intrinsic formal cause of (a) that substance’s being and (b) that substance’s belonging to the species that it does. A substantial form is a form intrinsic to x that explains the fact that x is actually F, where F is a feature that x cannot gain or lose without ceasing to exist, for example, Socrates’ property being an animal.

A third sense of formal cause for Thomas is the pattern or definition of a thing insofar as it exists in the mind of the maker. Thomas calls this the exemplar formal cause. For example, the form of a house can exist insofar as it is instantiated in matter, for example, in a house. However, the form of (or plan for) a house can also exist in the mind of the architect, even before an actual house is built. This latter sense of formal cause is what we might call the exemplar formal cause. For Thomas, following St. Augustine, some of the ideas of God are exemplar formal causes in this sense, for example, God’s idea of the universe in general, God’s idea of what-it-is-to-be a human being, and so forth, function, as it were, as plans or archetypes in the mind of the Creator for created substances.

iv. The Final Cause

The final cause of an object O is the end, goal, purpose, or function of O. Some material objects have functions as their final causes, namely, that is, artifacts and the parts of organic wholes. For example, the function of a knife is to cut, and the purpose of the heart is to pump blood. Therefore, the final cause of the knife is to cut; the final cause of the heart is to pump blood. Thomas thinks that all substances have final causes. However, Thomas (like Aristotle) thinks of the final cause in a manner that is broader than what we typically mean by function. It is a mistake, therefore, to think that all substances for Thomas have functions in the sense that artifacts or the parts of organic wholes have functions as final causes (we might say that all functions are final causes, but not all final causes are functions). For example, Thomas does not think that clouds have functions in the sense that artifacts or the parts of organic wholes do, but clouds do have final causes. In the broadest sense, that is, in a sense that would apply to all final causes, the final cause of an object is an inclination or tendency to act in a certain way, where such a way of acting tends to bring about a certain range of effects. For example, a knife is something that tends to cut. A cloud is a substance that tends to interact with other substances in the atmosphere in certain ways, ways that are not identical to the ways that either oxygen per se or nitrogen per se tends to interact with other substances.

For Thomas, the final cause is “the cause of all causes” (On the Principles of Nature, ch. 4) and so the final, formal, efficient, and material causes go “hand in hand.” If an object has a tendency to act in a certain way, for example, frogs tend to jump and swim, that tendency—final causality—requires that the frog has a certain formal cause, that is, it is a thing of a certain kind. In addition, things that jump and swim must be composed of certain sorts of stuffs and certain sorts of organs. Frogs, since they are by nature things that flourish by way of jumping and swimming, are composed of bone, blood, and flesh, as well as limbs that are good for jumping and swimming. Finally, a frog’s jumping is something the frog does insofar as it is a frog, given the frog’s form and final cause. That is to say, it is clear that the frog acts as an efficient cause when it jumps, since a frog is the sort of thing that tends to jump (rather than fly or do summersaults). Contrast the frog that is unconscious and pushed such that it falls down a hill. In so falling, the frog is not acting as an efficient cause.

As we have seen, some final causes are functions, whereas it makes better sense to say that some final causes are not functions but rather ends or goals or purposes of the characteristic efficient causality of the substances that have such final causes. In closing this section, we can note that some final causes are intrinsic whereas others are extrinsic. According to Thomas, each and every substance tends to act in a certain way rather than other ways, given the sort of thing it is; such goal-directedness in a substance is its intrinsic final causality. However, sometimes an object O acts as an efficient cause of an effect E (partly) because of the final causality of an object extrinsic to O. Call such final causality extrinsic. For example, John finds Jane attractive, and thereby John decides to go over to Jane and talk to her. John’s own desire for happiness, happiness that John currently believes is linked to Jane, is part of the explanation for why John moves closer to Jane and is a good example of intrinsic formal causality, but Jane’s beauty is also a final cause of John’s action and is a good example of extrinsic final causality.

d. The Sources of Knowledge: Thomas’ Philosophical Psychology

Thomas thinks there are different kinds of knowledge, for example, sense knowledge, knowledge of individuals, scientia, and faith, each of which is interesting in its own right and deserving of extended treatment where its sources are concerned. For present purposes, we shall focus on what Thomas takes to be the sources of knowledge requisite for knowledge as scientia, and, since Thomas recognizes different senses of scientia, what Thomas takes to be the sources for knowledge as a scientific demonstration of a proposition in particular.

As we have seen, if a person possesses scientia with respect to some proposition p for Thomas, then he or she understands an argument that p such that the argument is logically valid and he or she knows the premises of the argument with certainty. Therefore, one of the sources of scientia for Thomas is the operation of the intellect that Thomas calls reasoning (ratiocinatio), that is, the act of drawing a logically valid conclusion from other propositions (see, for example, ST Ia. q. 79, a. 8). Reasoning is sometimes called by Thomists, the third act of the intellect.

How do we come to know the premises of a demonstration with certainty? Our coming to know with certainty the truth of a proposition, Thomas thinks, potentially involves a number of different powers and operations, each of which is rightly considered a source of scientia. Before we speak of the intellectual powers and operations (in addition to ratiocination) that are at play when we come to have scientia, we must first say something about the non-intellectual cognitive powers that are sources of scientia for Thomas.

Thomas agrees with Aristotle that the intellectual powers differ in kind from the sensitive powers such as the five senses and imagination. Nonetheless, Thomas also thinks that all human knowledge in this life begins with sensation. Even our knowledge of God begins, according to Thomas, with what we know of the material world. Since God, for Thomas, is immaterial, the claim that “knowledge… begins in sense” (Disputed Questions on Truth, q. 1, a. 11, respondeo) should not be thought to mean that knowledge of x requires that we can form an accurate image of x. Thomas’ claim rather means that knowledge of any object x presupposes some (perhaps prior) activity on the part of the senses. Indeed, Thomas thinks that sensation is so tightly connected with human knowing that we invariably imagine something when we are thinking about anything at all. Of course, if God exists, that means that what we imagine when we think about God bears little or no relation to the reality, since God is not something sensible. Given the importance of sense experience for knowledge for Thomas, we must mention certain sense powers that are preambles to any operation of the human intellect.

In addition to the five exterior senses (see, for example, ST Ia. q. 78, a. 3), Thomas argues that a capacious account of human cognition requires that we mention various interior senses as preambles to proper intellectual activity (see, for example, ST Ia. q. 78, a. 4). For in order for perfect animals (that is, animals that move themselves, such as horses, oxen, and human beings [see, for example, Commentary on Aristotle’s De Anima, n. 255]) to make practical use of what they cognize by way of the exterior senses, they must have a faculty that senses whether or not they are, in fact, sensing, for the faculties of sight, hearing, and so forth themselves do not confer this ability. In addition, none of the exterior senses enables their possessor to distinguish between the various objects of sense, for example, the sense of sight does not cognize taste, and so forth. Therefore, the animal must have a faculty in addition to the exterior senses by which the animal can identify different kinds of sensations, for example, of color, smell, and so forth with one particular object of experience. We might think that it is some sort of intellectual faculty that coordinates different sensations, but not all animals have reason. Therefore, animals must have an interior sense faculty whereby they sense that they are sensing, and that unifies the distinct sensations of the various sense faculties. Thomas calls this faculty, following Avicenna, the common sense (not to be confused, of course, with common sense as that which most ordinary people know and professors are often accused of not possessing). Since, for Thomas, human beings are animals too, they also possess the faculty of common sense.

In addition to the common sense, Thomas argues that we also need what philosophers have called phantasy or imagination to explain our experience of the cognitive life of animals (including human beings). For, clearly, perfect animals sometimes move themselves to a food source that is currently absent. Therefore, such animals need to be able to imagine things that are not currently present to the senses but have been cognized previously in order to explain their movement to a potential food source. On the assumption that, in corporeal things, to receive and retain are reduced to diverse principles, Thomas argues the faculty of imagination is thus distinct from the exterior senses and the common sense. He also notes that imagination in human beings is interestingly different from that of other animals insofar as human beings, but not other animals, are capable of imagining objects they have never cognized by way of the exterior senses, or objects that do not in fact exist, for example, a golden mountain.

In Thomas’ view, we cannot explain the behavior of perfect animals simply by speaking of the pleasures and pains that such creatures have experienced. Thus, we need to posit two additional powers in those animals. The estimative power is that power by which an animal perceives certain cognitions instinctively, for example, the sheep’s cognition that the wolf is an enemy or the bird’s cognition that straw is useful for building a nest (for neither the sheep nor the bird knows this simply by way of what it cognizes by way of the exterior senses). The memorative power is that power that retains cognitions produced by the estimative power. Since (a) the estimative sense and common sense are different kinds of powers, (b) the common sense and the imagination are different kinds of powers, and (c) the estimative power can be compared to the common sense whereas the memorative power can be compared to the imagination, it stands to reason that the estimative power and the memorative power are different powers.

Just as intellect in human beings makes a difference in the functioning of the faculty of imagination for Thomas, so also does the presence of intellect in human beings transform the nature of the estimative and memorative powers in human beings. As Thomas notes, this is why the estimative and memorative powers have been given special names by philosophers: the estimative power in human beings is called the cogitative power and the memorative power is called the reminiscitive power. The cogitative power in human beings is that power that enables human beings to make an individual thing, event, or phenomena, qua individual thing, event, or phenomena, an object of thought. For example, if Joe comes to believe “this man is wearing red,” he does so partly in virtue of an operation of the cogitative power, since Joe is thinking about this man and his properties (and not simply man in general and redness in general, both of which, for Thomas, are cognized by way of an intellectual and not a sensitive power; see below). Similarly, if I come to think, “I should not steal,” I do so partly by way of my cogitative power according to Thomas insofar as I am ascribing a property to an individual thing, in this case, myself. As for the reminiscitive power, it enables its possessor to remember cognitions produced by the cogitative power. In other words, it helps us to remember intellectual cognitions about individual objects. For example, say that I am trying to remember the name of a particular musician. I employ the reminiscitive power when I think about the names of other musicians who play on recordings with the musician whose name I cannot now remember but want to remember.