Intuitionism in Mathematics

In the philosophy of mathematics, intuitionism stems from the view originally developed by L. E. J. Brouwer that mathematics derives from intuition and is a creation of the mind. This view is prefigured most notably by Kant, Kronecker, Poincaré, Borel, and Lebesgue. Intuitionism maintains that a mathematical object exists only if it has been constructed and that a proposition is true only if a certain construction that realizes its truth has been carried out. Thus, intuitionism generally entails a form of anti-realism in ontology and truth-value, for mathematical objects exist and mathematical propositions have truth-values but never independently of our limited human cognitive faculties.

Intuitionism can also be understood as a reaction to Cantor’s set theory due to its attempt to tame the infinity in mathematics by accepting only potentially infinite objects, namely, actually finite objects which can always be extended into larger finite objects. In this respect, intuitionism preserves the spirit of ancient Greek mathematics, where actual infinity used to be avoided by techniques such as the method of exhaustion. In his systematic development of a new foundation of mathematics without actually infinite collections, Brouwer was famously led to abandon the law of excluded middle and to introduce a new finitary class of objects called “choice sequences” in order to reconstruct the theory of the continuum.

Intuitionism is one of the three major views that dominated debates in the foundations of mathematics during the first half of the 20th century, along with logicism and formalism. It maintains against logicism that logic is merely a part of mathematics and against formalism that mathematics has meaning and is unformalizable. Intuitionism is also the only school among the three that was in effect largely reinforced by Gödel’s incompleteness results. Although it is classical mathematics and not intuitionistic mathematics that remains widely practiced, intuitionism has born many fruits in philosophy, mathematics, and computer science. Moreover, in addition to the historical significance of intuitionism, topics in its mathematics, logic, and philosophy continue to be actively explored.

This article surveys intuitionism as a philosophy of mathematics, with emphasis on the philosophical views endorsed by Brouwer, Heyting, and Dummett. Some preliminary remarks are in order. The term “intuitionism” is not synonymous with “constructivism”, an umbrella term that roughly refers to any particular form of mathematics that adopts “we can construct” as the appropriate interpretation of the phrase “there exists”. However, intuitionism remains one of the most prominent varieties of constructive mathematics. The curious reader can see the related article constructive mathematics for background. For more on the intuitionistic rejection of actual infinities, see also the article on the infinite. Finally, because intuitionism advocates a revision of classical mathematics, a certain amount of mathematical knowledge is required to fully appreciate some parts of this article, most importantly in the section on intuitionistic analysis. Readers can check any introductory textbook on classical real analysis or topology if they are not familiar with the terminology. Some familiarity with basic set theory is also presupposed in the first section on Brouwer, in particular regarding transfinite ordinals and uncountable cardinalities. Since the focus is intuitionistic mathematics, intuitionistic logic is not presented in this article. But for reference the appendix includes a list of notable theorems and non-theorems of intuitionistic logic.

Table of Contents

1. Brouwer

The development of non-Euclidean geometry in the eighteen century put some serious pressure on the status of space as a pure form of intuition, for it is hard to determine which geometry best describes the space of our experience. Intuitionism represents Brouwer’s attempt to revise Kant’s philosophy of mathematics by renouncing the intuition of space altogether and developing a stronger commitment to the pure intuition of time. Simply put, Brouwer views all his intuitionistic mathematics as a product of temporal intuition. This means in particular that Brouwer is open to the use of the tools of analytic geometry to found geometry on real-number coordinates without appeal to spacial intuition.

The development of non-Euclidean geometry in the eighteen century put some serious pressure on the status of space as a pure form of intuition, for it is hard to determine which geometry best describes the space of our experience. Intuitionism represents Brouwer’s attempt to revise Kant’s philosophy of mathematics by renouncing the intuition of space altogether and developing a stronger commitment to the pure intuition of time. Simply put, Brouwer views all his intuitionistic mathematics as a product of temporal intuition. This means in particular that Brouwer is open to the use of the tools of analytic geometry to found geometry on real-number coordinates without appeal to spacial intuition.

According to Brouwer, mathematics is a human mental activity independent of language; mathematical objects exist only as mental constructions given in intuition; and there are no mathematical truths which are not graspable by intuition. This means that Brouwer is committed to a radical version of anti-realism better characterized as a form of mathematical idealism in ontology and truth-value: both the existence of mathematical objects and the truth-values of mathematical propositions depend on the mind.

Brouwer proposed various articulations of intuitionism throughout his career. The germ of his basic views on mathematical intuition, logic, and language can be traced back as far as his dissertation on the foundation of mathematics (Brouwer 1907). This section concentrates on the presentations found in Brouwer’s late writings. Their main distinctive feature is that the development of intuitionistic mathematics out of intuition is more methodically described by means of two acts (Brouwer 1952, 1954, 1981). These two acts are performed by an idealized mind known as the creating subject. The most comprehensive formulations of the background philosophy that he adopted to justify his two acts of intuitionism can be found in (Brouwer 1905, 1929, 1933, 1948b). The following sections examine each one of these acts in turn and discuss the role they play in Brouwer’s philosophical justification of his intuitionistic mathematics.

a. The First Act of Intuitionism

Intuitionistic mathematics is a creation of the mind and independent of language. Brouwer emphasizes this mental dimension of intuitionism with the first act, which at the same time separates mathematics from language and introduces the “intuition of twoity” as the foundation on which the whole edifice of intuitionistic mathematics rests:

[…] Intuitionistic mathematics is an essentially languageless activity of the mind having its origin in the perception of a move of time. This perception of a move of time may be described as the falling apart of a life moment into two distinct things, one of which gives way to the other, but is retained by memory. If the twoity thus born is divested of all quality, it passes into the empty form of the common substratum of all twoities. And it is this common substratum, this empty form, which is the basic intuition of mathematics (Brouwer 1981, pp. 4-5).

As this is a rather brief and difficult passage, the rest of this subsection takes a closer look at the mental construction of mathematical objects according to the intuition of twoity and explores the autonomy of intuitionistic mathematics from logic and language. This article draws from other works by Brouwer to clarify these aspects of the first act.

i. Mental Construction in Intuition

The empty twoity is the form “one thing and then another thing” shared by all twoities, where a twoity is a pair of a first sensation followed by a second one. We intuit a twoity by perceiving the succession of two experiences in time, which is understood not in the external sense of scientific time but in the internal sense of our time consciousness. For example, suppose that we listen to the sounds of two successive ticks of a clock. One tick is heard at the initial present stage of our awareness, then as the second tick is heard at a new stage, the first tick does not completely disappear from consciousness but is retained in our memory as just past. Finally, a twoity that pairs these sounds is experienced by thinking of both ticks together:

[…] The basic intuition of mathematics (and of every intellectual activity) as the substratum, divested of all quality, of any perception of change, a unity of continuity and discreteness, a possibility of thinking together several entities, connected by a ‘between’, which is never exhausted by the insertion of new entities. Since continuity and discreteness occur as inseparable complements, both having equal rights and being equally clear, it is impossible to avoid one of them as a primitive entity, trying to construe it from the other one, the latter being put forward as self-sufficient; in fact it is impossible to consider it as self-sufficient (Brouwer 1907, p. 8).

Some comments on the passage quoted above are needed. The same formulation of the intuition of twoity found in Brouwer’s statement of the first act is paraphrased in almost verbatim style multiple times in his later writings, but, as we can see above, he maintained the ideas already in his dissertation (Brouwer 1907, p. 9). The greatest difference is that in these early formulations he puts emphasis on a “between” that connects the two elements of our perception of two things in time and he insists that the discrete and continuum are both inseparable primitive complements of each other. From Brouwer’s introduction of the second act on, he almost never speaks of the irreducible continuum, but still stresses the creation of the between with a twoity (Brouwer 1981, p. 40). The postulation of choice sequences and species with the second act merely allows Brouwer to recognize the intuitive continuum as a “matrix of ‘point cores’” and study it mathematically.

Intuitionistically, the positive integers 1, 2, 3, … are represented in terms of finite ordinals. The intuition of twoity generates in the first instance the ordinal numbers two and one, as well as all other finite ordinal numbers by the indefinite repetition of the process. As the empty twoity is the form of two paired things, it can be viewed as a pair of units. One of its elements is defined as the number 1 and the empty twoity itself is the number2. The discrete fragment of intuitionistic mathematics arises from the basic operation of mentally constructing new twoities in intuition by pairing the empty twoity and its units:

This empty two-ity and the two unities of which it is composed, constitute the basic mathematical systems. And the basic operation of mathematical construction is the mental creation of the two-ity of two mathematical systems previously acquired, and the consideration of this two-ity as a new mathematical system (Brouwer 1954, p. 2).

We should stress that, as for Brouwer the empty twoity is intuited before its elements are, the number 2 is constructed before the number 1 in his mathematical universe. This is because 1 can only be constructed by projecting a unit out of the empty twoity. The intuitive nature of projection is often emphasized by van Atten (2004, §1.1; 2024, p.63). Brouwer thinks we could not have an empty unity as the starting point because the operation of adding another unit would already presuppose the intuition of twoity to form a pair of units:

The first act of construction has two discrete things thought together […] F. Meyer […] says that one thing is sufficient, because the circumstance that I think of it can be added as a second thing; this is false, for exactly this adding (i.e. setting it while the former is retained) presupposes the intuition of two-ity; only afterwards this simplest mathematical system is projected on the first thing and the ego which thinks the thing (Brouwer 1907, p. 179, fn. 1).

Indeed, the construction of all the positive integers proceeds as follows:

The inner experience (roughly sketched):

twoity;

twoity stored and preserved aseptically by memory;

twoity giving rise to the conception of invariable unity;

twoity and unity giving rise to the conception of unity plus unity;

threeity as twoity plus unity, and the sequence of natural numbers;

mathematical systems conceived in such a way that a unity is a mathematical system and that two mathematical systems, stored and aseptically preserved by memory, apart from each other, can be added; etc. (Brouwer 1981, p. 90).

It is important to note that Brouwer omits the construction of the number zero here. It is unclear whether this has to do with its lack of a direct representation in intuition, since it was common to exclude zero as a natural number during his time. In any event, Brouwer introduces zero into his mathematical ontology later as an integer. Kuiper (2004, ch. 2) proposes alternative ways to accommodate zero and describes constructions of the natural numbers and rationals from the intuition of twoity relying on the early notion of betweenness advocated in Brouwer’s dissertation. A recent interpretation of the construction of the positive integers based on Brouwer’s mature writings is developed by Bentzen (2023b, section 3.1) based on intuitive operations of pairing, projecting, and recollecting.

The intuition of twoity does not just yield the positive integers. Brouwer maintains that the first infinite ordinal number \(\omega\) and all subsequent countable ordinals can be obtained by the indefinite repetition of the creation of twoities in time (Brouwer 1907, pp. 144-145). The first act of intuitionism is therefore also able to produce the sequence of mathematical objects \(\omega,\omega+1,\omega+2,…,\omega + \omega, …,\omega \times \omega,\omega \times \omega + 1,…\), but it excludes uncountable ordinals. In fact, in his early writings, Brouwer can be found stressing that intuitionistic mathematics only recognizes the existence of countable sets (Brouwer 1913, p. 58). Recall that a set is countable if its elements can be put in a one-to-one correspondence with the elements of a subset of the set of natural numbers. Just as in classical mathematics, the continuum also remains uncountable intuitionistically. Of course, this does not mean that Brouwer is prepared to deny the existence of the continuum, but only that it cannot be reduced to a totality that is supposed to exist as a whole (Brouwer 1907, pp. 144-149). Intuitionistically, we can only make sense of an uncountable set as a “denumerably unfinished set”, namely, a set such that as soon as we think we have constructed more elements than those in a countable subset of it, we can immediately find new elements which should also belong to it. Notice that, after the introduction of the second act, this vague notion of set assumed in Brouwer’s early writings is abandoned in favor of his mature conception of species. In his later works the word “set” (Menge) is reserved for a spread, a particular kind of species of choice sequences. Choice sequences and spreads are examined in a later section.

ii. Logic and Language

Brouwer stresses that language can only play a non-mathematical auxiliary role in the construction of objects out of the intuition of twoity. For example, language can be used as a memory aid and to communicate some mathematical constructions to others, but what is written down can only be justified as an expression of our mental acts. This is why Brouwer maintains against Hilbert that freedom from contradiction can never guarantee existence. From the intuitionistic standpoint, to exist is to be constructed in intuition:

It is true that mathematics is quite independent of the material world, but to exist in mathematics means: to be constructed by intuition; and the question whether a corresponding language is consistent, is not only unimportant in itself, it is also not a test for mathematical existence (Brouwer 1907, p. 177).

In its purest form, intuitionistic mathematics consists of acts of construction in intuition. Logic and language only come into play later in its communication. This independence of mathematics from logic immediately leads to a repudiation of logicism, for, intuitionistically, mathematics is not part of logic. Rather, it is logic that is a part of mathematics:

While thus mathematics is independent of logic, logic does depend upon mathematics: in the first place intuitive logical reasoning is that special kind of mathematical reasoning which remains if, considering mathematical structures, one restricts oneself to relations of whole and part; the mathematical structures themselves are in no respect especially elementary, so they do not justify any priority of logical reasoning over ordinary mathematical reasoning (Brouwer 1907, p. 127).

Despite Brouwer’s general downplay of logic, he often stresses that if our mathematical constructions are put into words, the logical principles of the law of identity, the law of noncontradiction, and the Barbara syllogism can always be used to arrive at linguistic descriptions of new constructions (Brouwer 1908, pp. 155-156).. Nevertheless, he notes that in general this cannot be said of the law of excluded middle as well, namely, the principle that states that either a proposition or its negation holds, for any proposition. The law of excluded middle must be rejected in intuitionistic mathematics because it is taken to mean that every mathematical proposition can either be proved or refuted. The constant presence of open problems in mathematics indicates that this is not the case:

The question of the validity of the principium tertii exclusi is thus equivalent to the question concerning the possibility of unsolvable mathematical problems. For the already proclaimed conviction that unsolvable mathematical problems do not exist, no indication of a demonstration is present (Brouwer 1908, p. 156).

The rejection of the law of excluded middle is very subtle. To avoid confusion, notice that intuitionism simply does not accept that this law is generally valid for every proposition. It is not denied that the law might hold for certain propositions. Indeed, Brouwer insists that there will always be admissible uses of the law of excluded middle when dealing with properties about finite sets (Brouwer 1981, pp. 5-6). This is because an exhaustive verification running through the elements of the set one by one will always terminate. This leads to a proof or refutation of the finitary proposition in question. But we have to be careful when working with infinite sets because an exhaustive verification is not available to us. The repudiation of the law of the excluded middle for infinite domains is a direct product of Brouwer’s view of intuitionistic mathematics as an activity of the finite human mind.

When discussing logic in the first act of intuitionism, Brouwer often connects the rejection of the law of excluded middle to the existence of what he calls “fleeing” properties. Roughly, a fleeing property is a property of the natural numbers such that for every individual number it can be decided whether it holds or not, but we do not know a particular number for which it holds, nor that there is no number for which it holds. Now, Brouwer often refused to adopt logical symbolism in his writings perhaps due to his aversion to formalization, but we will not hesitate to employ formal notation in this entry for more precision. We say that a property \(A\) on the natural numbers is fleeing if the following three conditions are met:

- we know that \(\forall n (A(n) \lor \neg A(n))\);

- it is not known so far whether \(\exists n A(n)\);

- it is not known so far whether \(\neg

\exists n A(n)\).

Every fleeing property therefore provides an unsettled instance of the excluded middle. Some properties may cease to be fleeing the moment it is found an \(n\) such that \(A(n)\) or if there emerges a proof that no such number exists, in which case \(\exists n A(n) \lor \neg \exists n A(n)\) is decided. But there will always be other fleeing properties available to us. In fact, every open problem about the natural numbers naturally gives rise to a fleeing property, as shown in the following example. Suppose that \(A(n)\) holds iff \(n\) is a counterexample to Goldbach’s Conjecture, which states that every even natural number greater than \(2\) is a sum of two primes. Since as of this writing this proposition remains a conjecture, we cannot tell whether there exists a counterexample nor whether it is impossible that a counterexample might exist. Yet, given any particular number we can, at least in principle, ignoring practical limitations of time, verify whether it is a counterexample or not because, once again, we are dealing with a decidable property over the natural numbers. Put differently, there exists an effective method for checking whether the property holds or not for each number.

Intuitionistic arithmetic is not quite different from its classical counterpart. One reason for their similarity is that equality between natural numbers is decidable, so \(\forall n \forall m (n = m \lor \neg n = m)\) is an intuitionistically valid instance of the law of excluded middle. This is why Brouwer repeatedly insists that on the basis of the first act alone classical discrete mathematics “can be rebuilt in a slightly modified form” (Brouwer 1952, p. 142). Yet, there remains several theorems from classical number theory that cannot be proved intuitionistically. Perhaps the most notable case in point is the absence of the least number principle, which asserts that if a property on the natural numbers has a witness then it has a least one. To be exact, it can be expressed symbolically as \(\exists n A(n) \to \exists n (A(n) \land \forall i (i < n \to \neg A(i)))\). Its failure in intuitionistic arithmetic is due to the presence of fleeing properties. To see this, let \(B\) be a property such that \(B(n)\) holds for all \(n > 0\) but \(B(0)\) holds iff \(\exists n A(n)\), where \(A\) is the property considered above tracking counterexamples to Goldbach’s Conjecture. If this conjecture is settled one day we can just pick another open problem to replace \(A\). If the least number principle were to hold for \(B\), we would already know whether \(\exists n A(n)\) or not. ==Given that \(A\) is a fleeing property, this is currently undecided (Posy 2020, section 2.2.1). Clearly there are some properties for which the least number principle holds. It is just not valid for every property in the intuitionistic setting as it is in classical number theory.

b. The Second Act of Intuitionism

We have seen that the first act of intuitionism postulates the construction of the positive integers in intuition as finite ordinals and all countable infinite ordinals. We also saw that intuitionistic arithmetic already diverges to some extent from classical arithmetic. It is however in its distinctive treatment of the continuum that the greatest differences between classical and intuitionistic mathematics begin to show. To arrive at a satisfactory approach to real analysis from the intuitionistic standpoint, Brouwer thought more powerful tools than those introduced in the first act are required. The second act postulates the admission of species and choice sequences into the domain of intuitionistic mathematical objects:

Admitting two ways of creating new mathematical entities: firstly in the shape of more or less freely proceeding infinite sequences of mathematical entities previously acquired (so that, for example, infinite decimal fractions having neither exact values, nor any guarantee of ever getting exact values are admitted); secondly in the shape of mathematical species, i.e. properties supposable for mathematical entities previously acquired, satisfying the condition that if they hold for a certain mathematical entity, they also hold for all mathematical entities which have been defined to be ‘equal to it, definitions of equality having to satisfy the conditions of symmetry, reflexivity and transitivity (Brouwer 1981, p. 8).

Once again, this is not an entirely clear formulation. In particular, Brouwer tends to be rather briefly worded in his articulations of what precisely a choice sequence is. The first place where choice sequences are accepted is (Brouwer 1914). However, it is not until later that they begin to be put to use in the intuitionistic modeling of the continuum by means of spreads. Without spending much time discussing these novel ideas, Brouwer simply introduces choice sequences as the paths through a spread (Brouwer 1918, p. 3). The notion of spread is examined more carefully when looking at species in a later section, but for now it will suffice to think of a spread as an infinitely branching tree described according to a certain law, where of course infinity is understood only in the sense of potential infinity. So, a choice sequence is viewed as a path of nodes growing indefinitely with some degree of freedom. While Brouwer does not go far beyond this initial vague explanation, he later revisits this characterization of choice sequences adding that we can restrict their freedom of continuation by a law after each choice as we wish (Brouwer 1925, fn. 3). Multiple passing remarks intended to elaborate on law restrictions can be found in his writings. For a period, Brouwer even hesitated about accepting higher-order restrictions, which allow for a restriction imposed on restrictions of choice of elements, and so on. But the details are unimportant for our purposes in this entry, given that the idea, first introduced in Brouwer 1942), was ultimately abandoned a decade later (Brouwer 1952, p. 142 fn.*). We shall therefore focus on the ordinary conception of choice sequence with first-order restrictions here. Readers interested in higher-order restrictions can see (van Atten and van Dalen 2002, pp. 331-335).

The above articulation of the second act also leaves out the two special ingredients that Brouwer invokes in his intuitionistic approach to real analysis, namely, his principles of continuity and bar induction. It is unclear whether Brouwer omitted them from his formulation of the second act because he viewed them as mere consequences of it. In any case, he never attempted to offer a justification for these principles in his writings, though as we shall see in the remainder of this section, they are far from being obvious. Regardless, the principles of continuity and bar induction are so important to intuitionistic analysis that it cannot be done without them. They are the ingredients that lead to notable results such as the uniform continuity theorem that actually contradict classical analysis. In the literature results like this are referred to as “strong counterexamples” because they reveal that intuitionistic analysis is not a merely restriction of its classical counterpart, as in the case of intuitionistic and classical arithmetic, but rather an incomparable alternative to it.

i. Choice Sequences and Continuity

Choice sequences are potentially infinite sequences of mathematical objects. That is, at every stage in time only a finite initial segment of the sequence has been constructed, but the sequence can always be continued with the inclusion of a new element. For example, if so far the creating subject has only constructed some initial segment \(\langle 7, 5, 12, 8, 23 \rangle\), they can later pick another number of their choosing to extend the sequence with, say \(42\). It is not possible to make an actually infinite number of choice of elements. Due to the inherently finite nature of the human mind the construction process can never be finished.

What is special about choice sequences and distinguishes intuitionism from all other variants of constructive mathematics such as Bishop’s brand of constructivism is that it is explicitly admitted that their elements need not be given by some law. Simply put, a law is any procedure that our minds can express by means of an algorithm. The notion of choice sequence also admits in addition to elements determined algorithmically a unique method of free choice that arbitrarily selects a new element. We sometimes say that these elements are chosen by the free will of the creating subject. In all his career Brouwer saw free choice as a necessary ingredient to go beyond the computable reals, the real numbers which can be computed by an algorithm and are classically countable. Heyting (1975, p. 607) notes that this conviction was invalidated when Bishop showed that the set of computable reals remains uncountable constructively if all functions admitted are algorithmic. In any case, choice sequences remain significant for their philosophical and mathematical interest.

It is time to take a closer look at what choice sequences are. Although, as we saw earlier, Brouwer does not actually say much about them, it is common in the literature to think of a choice sequence as a generalization of an algorithmic sequence (Troelstra 1977, section 1.7), that is, a sequence whose elements are all determined by an algorithm. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, we shall follow the usual convention of denoting algorithmic sequences using the small Latin letters \(f, g, …\) and choice sequences using the small Greek letters \(\alpha, \beta, …\) Now, to see how this generalization works, note that, given any algorithmic sequence \(f\), an algorithm determines exactly one value \(f(n)\) for every positive integer \(n\). In contrast, given a choice sequence \(\alpha\), we still retain \(\alpha(n)\) as a value assigned for each \(n\), but we cannot require that this value be effectively calculable by an algorithm. In general, at every stage only an initial segment may be known. But recall that Brouwer (1925, 1942, 1952) does emphasize that law restrictions can be imposed at will to the freedom of continuation of the sequence after each step of its construction. To express this more precisely, we may demand that for any finite initial segment \(\langle \alpha(1), …, \alpha(n) \rangle\) for some positive integer \(n\), there is an algorithm determining a non-empty range of possible values for \(\alpha(n+1)\) onward. Simply put, instead of stipulating that an algorithm determines exactly one value, as in the case of algorithmic sequences, we just require that at each stage of the construction of a choice sequence its range of possible further values be determinable algorithmically. We can calculate the restrictions and even subject them to further restrictions at some later point in the ever-unfinished construction of the sequence. What need not be calculable ahead of time is the exact value of \(\alpha(n)\) for every \(n\). In sum, a choice sequence is given by an initial finite segment and a law that determines at every subsequence step of the sequence its range of possible future values. From this it immediately follows that, from the intuitionistic standpoint, an algorithmic sequence is nothing but a special case of a choice sequence in which its range of possible values always has exactly one element.

Now, let us look at some examples of choice sequences to illustrate the idea. The common practice in the literature is to distinguish between at least two different kinds of choice sequences depending on the information available to the creating subject:

- lawlike sequences are choice sequences that are algorithmic. The simplest example is the sequence of positive integers, whose elements are completely determined by the number one and an effective rule that repeatedly applies the successor operation. But any more complex sequence calculable by an algorithm will do.

- lawless sequences are choice sequences subject to no law restrictions. At each stage in their construction only a finite initial segment of them can be known. More precisely, after a fixed initial segment of the sequence is stipulated at the outset, there is no law limiting the range of possible future values. Perhaps the most well-known example is that of a sequence obtained by throwing a die with six faces \(\{1,2,3,4,5,6\}\). For example, if we let \(\alpha(1)=1\) be its initial segment, from this point on we cannot know in advance nothing more than that \(\alpha(i) \in \{1,2,3,4,5,6\}\) for all \(i > 1\). The terminology “lawless” was suggested by Gödel and introduced by (Kreisel 1968).

Some remarks are in order to avoid confusion. First, note that lawlike sequences are to be distinguished from general recursive sequences, for, as Heyting (1966) observes, the intuitionist does not accept Church’s thesis with respect to laws, which essentially states that every lawlike sequence can be computed by a Turing machine. Even if it might be compelling to identify “mechanically computable” with “calculable by a Turing machine”, there are still good reasons to abstain from Church’s thesis. Given that intuitionism is a product of the human mind, a law is understood as what is humanely computable, and that is to be distinguished from a mechanically computable process (Troelstra 1977, section 1.3). From the intuitionistic perspective, as the states of a mental calculation involve intentional aspects having to do with the basic mathematical intuition, for all we know, they might go beyond the artificial states of a Turing machine (Tieszen 1989, p. 81). In Brouwer’s work the notion of a law is accepted as primitive and left without a rigorous definition. His introduction of choice sequences predates the work of Church and Turing by nearly two decades, but even after that it appears that he never has commented on the status of Church’s thesis. For more on the acceptance of this thesis, see (McCarty 1987). Although most intuitionists tend to reject Church’s thesis, McCarty provides a systematic investigation of different ways in which it can be understood in intuitionistic mathematics. The alternative variety of constructivism that accepts this thesis is known as recursive constructivism.

Second, in the example given above of a lawless sequence, we have limited ahead of time the domain of the sequence to a proper subset of the positive integers. Put it differently, we have restricted all elements of the sequence to \(\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}\) from the very beginning, ruling out any other positive integers from the lawless sequence. However, how can this be possible if lawless sequences are supposed to be subject to no law restrictions? There is no contradiction, for our freedom to create a lawless sequence guarantees that the range of the sequence can be any range we want. We are always allowed to impose a “general a priori restriction” that all values belong to a certain domain (Troelstra 1977, section 2.2). It is conceivable, for instance, to have a lawless sequence of coin tosses that only has values in \(\{1, 2 \}\) depending on whether we get heads or tails. What we cannot do is to impose a law during the construction of a lawless sequence to further restrict that domain.

Finally, the distinction between lawlike and lawless sequences is not exhaustive. It is a very common mistake to assume that all non-lawlike sequences are lawless. We simply call a sequence non-lawlike if it is a choice sequence that is not lawlike. Of course, every lawless sequence is non-lawlike by definition, but the converse is false. The following example illustrates why. Given two lawless sequences \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), define a new choice sequence \(\gamma\) by \(\gamma(k)=\alpha(k)+\beta(k)\). Then \(\gamma\) is subject to a law restriction, but is not given algorithmically. Another example is the choice sequence \(\delta\) which oscillates between \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) on even and odds arguments, that is, \(\delta(2k)=\alpha(k)\) and \(\delta(2k+1)=\beta(k)\). In general, non-lawlike sequences enjoy an intermediate degree of freedom, involving both law restrictions and free choice. The best well-known example of a class of choice sequences that exhibit this intermediate nature is that of hesitant sequences (Troelstra and van Dalen 1988, section 4.6.2), namely, choice sequences that start out lawless but a law may or may not be adopted to determine future values. If a law is accepted from the very beginning or never accepted then the particular sequence is in fact lawlike or lawless respectively, but it remains neither if the antecedent is not the case.

Since choice sequences are permanently in a process of growth and can never be admitted as completed mathematical objects, how can we do mathematics with them? First of all, when dealing with choice sequences, we must carefully distinguish between intensional and extensional equality. As one might expect, two choice sequences \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are extensionally equal iff they have the same values for the same arguments: \[\alpha = \beta \leftrightarrow \forall n \alpha (n) = \beta (n).\]

Strictly speaking, however, we should also distinguish between the laws according to which the sequence might be given to us (Dummett 1977, section 3.1). Simply put, two sequences might be extensionally equal but still be intensionally different if they are given by different laws. We commonly write \(\alpha \equiv \beta\) to indicate that \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are intensionally equal. We are often especially interested in properties that respect extensionality in intuitionistic mathematics. We say that a property \(A\) of choice sequences is extensional iff the following holds: \[\forall \alpha \forall \beta (A(\alpha) \land \alpha = \beta \to A(\beta) ).\]

It is worth noting that a choice sequence might be extensionally equal to a lawlike sequence but not necessarily given as a lawlike one. It is not even generally possible to determine when a supposedly lawless sequence actually turns out to determine a lawlike sequence extensionally. To borrow Borel’s metaphor, if we give an infinite amount of time to a monkey hitting number keys at random in a typewriter, then in principle the monkey could end up reproducing the Fibonacci sequence, for instance. That is to say, the creating subject cannot be certain that they are not following an unknown law when constructing a choice sequence until the very end, and yet the construction will never end. Let me clarify that this does not mean that a lawless sequence can in fact be lawlike. We may say the sequence is intensionally lawless but extensionally lawlike in the sense above. In the remainder of this subsection, it is assumed that all properties are extensional. Now, to motivate Brouwer’s principle of continuity, it might be useful to start with some general remarks on the acceptance of the axiom of choice in intuitionism. The simplest version of the axiom states that if for every natural number \(n\) there is some \(m\) such that \(A(n,m)\), there exists a function \(f\) such that \(A(n,f(n))\) for every \(n\). In symbols: \[\forall n \exists m A(n,m) \to \exists f \forall n A(n,f(n)).\]

To avoid confusion, we stress that here \(f\) denotes a function and not a lawlike sequence. The above principle is in fact perfectly valid intuitionistically. It is a direct consequence of the meaning of the intuitionistic logical constants, for the antecedent has a form \(\forall x \exists y A(x,y)\) and its truth presupposes a procedure that ransforms every object \(x\) into a pair that contains a specific \(y\) and a proof that \(A(x,y)\). We will look more closely at this informal semantics when studying Heyting’s meaning explanations in 2.2. The point is that the constructive meaning of existence yields an “operation” that in this particular case serves as a choice function because intensional and extensional equality coincide. Therefore, controversies surrounding the axiom of choice arise in intuitionistic mathematics only when intensional and extensional equality diverge. The reader is referred to (McCarty et. al. 2023) for a comprehensive overview of the status of the axiom of choice in various intuitionistic and constructivist systems. In the general version of the axiom of choice, we drop the above restriction to the natural numbers and consider any set (or rather species). In this form, the axiom is false because intensional and extensional equality need not always agree. We have already seen that that is not the case for choice sequences in general.

What does this have to do with continuity? We can think of a continuity principle as a more assertive version of the axiom choice that tells us how to manipulate choice sequences. If instead of the natural number \(n\) we consider a choice sequence \(\alpha\) in the above formula, the resulting version of the axiom of choice \(\forall \alpha \exists m A(\alpha,m) \to \exists f

\forall \alpha A(\alpha,f(\alpha))\) is false. Even when \(A\) is an extensional property, the function \(f\) need not respect extensional equality. So, if \(\alpha = \beta\) then \(f(\alpha) = f(\beta)\) might not hold, unless \(\alpha \equiv \beta\) also holds (Dummett 1977, p. 57). It is possible that \(A(\alpha,f(\alpha))\) is true but not \(A(\beta,f(\beta))\) or vice-versa, contradicting the assumption that \(A\) is an extensional property. To overcome this obstacle, intuitionists need to impose an additional requirement to the admissible choice functions to guarantee the preservation of extensional propertiesand this is where continuity enters the picture. One solution is to restrict them to those belonging to a class of “neighborhood functions” \(\mathbf{K}\) that allow us to determine their value in a finitistic way. They are usually denoted by the letter “\(e\)” rather than “\(f\)” in the literature because of their special status. If \(e \in \mathbf{K}\), then \(e(\alpha)\) is calculable from a finite amount of information known about \(\alpha\), such as the finite initial segment of the sequence or the law restrictions imposed up until a certain stage. The value \(e(\alpha)\) never depends on all the elements of the sequence, but only from what we know about \(\alpha\) at some point. This means that such a function \(e\) is in effect only ever applied to initial segments.

So, as the domain of a neighborhood function actually consists of finite sequences, strictly speaking, the notation “\(e(\alpha)\)” makes a category mistake. However, we can treat \(e(\alpha)\) as an abbreviation for the value of \(e\) on the smallest sufficiently long initial segment of \(\alpha\). Put another way, if, intuitively, \(e(\overline{\alpha}(n))=0\) means that the initial segment \(\overline{\alpha}(n)\) is not sufficiently long enough to compute the value of \(e\) for \(\alpha\), then \[e(\alpha) \text{ is defined iff } \exists n (e(\overline{\alpha}(n)) > 0),\] \[e(\alpha)=k \text{ iff } \exists n (\overline{\alpha}(n) = k + 1) \land \forall m (m < n \to \overline{\alpha}(n) = 0).\]

Now, \(e(\alpha)=e(\beta)\) holds because \(e\) is continuous in a precise sense (Dummett 1977, p. 58). Although this is not to place to enter into detail, the basic idea is this. Suppose for the moment that we are dealing only with arbitrary, unrestricted choice sequences. Then the topological space in question can be studied as a Baire space, whose neighborhoods consist of all species of choice sequences sharing the same initial segment of some length. Readers need not worry if the concept of a Baire space is unfamilar to them, for it essentially describes the universal spread soon to be discussed in 1.2.2. Topologically, \(e\) serves as a continuous function from this Baire space to the natural numbers with the discrete topology, the space consisting of every subset of the natural numbers as a neighborhood. Continuity means that, given any choice sequence \(\alpha\), for every neighborhood \(N(e(\alpha))\), there exists a neighborhood \(M(\alpha)\) such that if \(\beta \in M(\alpha)\) then \(e(\beta) \in N(e(\alpha))\). The equality \(e(\alpha)=e(\beta)\) immediately follows because, under the discrete topology, the singleton \(\{ e(\alpha) \}\) is a neighborhood of its element. Notice that we only focused our attention on the universal spread in the example above for the sake of simplicity, but similar considerations also apply to neighborhood functions associated with choice sequences that admit restrictions.

Once again, it is not our interest to dive into topology in this survey. As far as intuitionism is concerned in the philosophy of mathematics, the important thing to keep in mind is that such a \(\forall\alpha\exists n\)-continuity principle results from the imposition of continuity to the otherwise problematic choice principle \(\forall \alpha \exists m A(\alpha,m) \to \exists f \forall \alpha A(\alpha,f(\alpha))\) mentioned above. The antecedent remains unchanged, but the consequent states that there exists a neighborhood function \(e\) such that for every \(\alpha\) for which \(e\) is defined, \(A(\alpha, e(\alpha)\) holds. If we write \(e(\alpha) > 0\) to mean that \(e\) is defined for \(\alpha\), then the resulting principle can be stated as follows:

\[\tag{C-N} \label{cn} \forall \alpha \exists n A(\alpha, n) \to \exists e \in \mathbf{K} \forall \alpha (e(\alpha) > 0 \to A(\alpha, e(\alpha))).\]

This is one of the formulations of Brouwer’s continuity principle. It is commonly described as the full version of continuity to distinguish it from a weaker formulation for the natural numbers that can be derived from it. Let the equality \(\overline{\alpha}(m) = \overline{\beta}(m)\) abbreviate the fact that the initial segments of length \(m\) of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) agree, which we can symbolically represent as \(\forall i < m (\alpha(i) = {\beta}(i))\). We can state the weak continuity principle as:

\[\tag{WC-N} \label{wcn} \forall \alpha \exists n A(\alpha, n) \to \forall \alpha \exists m \exists n \forall \beta (\overline{\beta}(m) = \overline{\alpha}(m) \to A(\beta, n)).\]

The only difference between these two principles is the consequent. Indeed, in (WCN) the requirement that there be a neighborhood function is dropped. Informally, the consequent says that given an \(\alpha\), we can find a fixed length \(m\) such that for some \(n\) and any \(\beta\) whose the initial segments of length \(m\) agrees with \(\alpha\), \(A(\beta,n)\) holds. As van Atten and van Dalen (2002) note, Brouwer used this continuity principle for the first time to show that the set of numerical choice sequences is not enumerable. They also investigate justifications for versions of the weak continuity principle (WC-N). As they point out, this principle is evident for lawless sequences because we never know more than a finite segment of them in advance. But for lawlike sequence it is less obvious since law restrictions might be taken into account.

These are not the only continuity principles considered in intuitionism. An even stronger form of continuity is usually discussed under the name of \(\forall\alpha\exists\beta\)-continuity. It can be regarded as a generalization of the full continuity principle (C-N) where the existential statement about numbers is instead about choice sequences. It is articulated by considering a partial higher-order function \(|\) that given a neighborhood function \(e\) and choice sequence \(\alpha\) returns a choice sequence \(e|\alpha\) if it satisfies some technical conditions (Dummett 1977, p. 60):

\[\tag{SC-N} \forall \alpha \exists \beta A(\alpha, \beta) \to \exists e \in \mathbf{K} \forall \alpha A(\alpha, e | \alpha).\]

The status of the \(\forall\alpha\exists\beta\)-continuity principle is more controversial. Dummett (1977, p. 222) sees this it as a dubious principle, as “it is far from plain that it is intuitionistically correct”. While it might initially be seen that \(\forall\alpha\exists\beta\)-continuity leads to contradictions in creating subject contexts, Posy (2020, pp. 73-74) explains that it is valid intuitionistically and that the clash only arises if one forgets about the restriction to extensional properties.

Continuity principles allow us to refute some classical theorems. It provides us with theorems that contradict results in classical mathematics. Iemhoff (2024) stresses that even the weak continuity principle implies the negation of a quantified version of the law of excluded middle \(\neg\forall \alpha (\forall n \alpha(n)=0 \lor \neg \forall n \alpha(n)=0)\). More precisely, unlike intuitionistic logic, which is not incompatible with classically valid principles, intuitionistic mathematics actually refutes classical logic (not just classical mathematics)! The full continuity principle can be used to prove that every total real function is continuous in intuitionistic analysis. The intuitionistic construction of the real numbers is discussed in the next sub-section. To be clear, however, it should be emphasized that discontinuous functions can be defined, but they are not total (Posy 2020, p. 35). For an overview of these and other consequences of the continuity principles, such as a derivation of weak continuity (WC-N) from full continuity (C-N), see (Dummett 1977, pp. 60-67). A more general mathematical account is given by (Veldman 2021, sections 12-13).

ii. Species, Spreads, and Bar Induction

Species are the closest analog in intuitionism to sets as used in classical mathematics. But at the same time they exhibit significant differences that should be emphasized. In a nutshell, a species is a property that previously constructed mathematical objects may possess. When a species \(S\) is defined by a certain property \(A\), we write \(S=\{x \mid A(x)\}\). If \(A(a)\) holds, we say that a formerly obtained object \(a\) is an element of \(S\) and we write \(a \in S\). Brouwer always highlights the following facts when introducing the notion of species in the second act:

1. a species can be an element of another species, but never an element of itself. That is to say that predicativity is a built-in feature of species. This is how the intuitionist is able to circumvent circularities like Russell’s paradox. In a sense, there is a clear resemblance with the theory of types (Heyting 1956b, section 3.2.3). The universe of species can be stratified into a hierarchy depending on their order: first-order species may only have elements which are not themselves given as species; second-order species may only have as elements objects given as first-order species and so on.

2. a species always has an equality relation defined among its elements. The equality associated with the definition of a species \(S\) must always be an equivalence relation \(R\) such that if \(a \in S\) and \(R(a,b)\) then \(b \in S\). We write \(a =_S b\) to denote \(R(a,b)\). This ternary equality relation is to be distinguished from the binary relations of intensional and extensional identity considered previously for choice sequences, for instance.

3. we can redefine the same species time and again. To understand why this is useful, recall that only for entities constructed prior to the definition of a species may we ask if they possess the corresponding property. When a species \(S\) is introduced no other mathematical object \(b\) constructed after this point in time can be a member of it, even if they turn out to satisfy the same property \(A\) that defined \(S\)! In order to accommodate this missing element, we can redefine the species \(S\) again after constructing \(b\). Thus, roughly speaking, a species can change their membership relation over time. We never lose its former elements but we might gain new ones after the redefinition.

Just as with the notion of a choice sequence, which necessarily grow over time, with species temporality is witnessed in the second act of intuitionism. This should not come as a surprise, for, as already seen earlier, intuitionistic mathematics is based on the intuition of time. Besides, like choice sequences, species are intrinsically intensional since two species are in fact one and the same only when given by the same property (van Atten 2004, pp. 6-7).

How are species used to construct the intuitionistic continuum? First, let us remark that the classical constructions of the set of integers \(\mathbb{Z}\) and rationals \(\mathbb{Q}\) are essentially acceptable intuitionistically, except that we are dealing with species instead. Moreover, it should be noted that they are not regarded as a finished totality. They can be defined with the usual equivalence relations by considering the equivalence classes as species. But due to the intensionality that species carry with them, we need to maintain some fine grained distinctions not present in classical set theory. For example, the subset of natural numbers in the integers \(\mathbb{N}_\mathbb{Z}\) and in the rationals \(\mathbb{N}_\mathbb{Q}\) are not identical species. The construction of the species \(\mathbb{R}\) is sometimes said to be analogous to the construction of the reals in terms of Cauchy sequences in classical mathematics. This is true in a sense, but the description downplays the role of choice sequences. In the intuitionistic approach to mathematics, the notion of choice sequence first comes into play in the definition of \(\mathbb{R}\) as the species of equivalence classes of convergent choice sequences of rationals (Heyting 1956b, section 3.1.1. Let \(\alpha=\langle r_i \rangle_i\) be a choice sequence of rational numbers. We say that \(\alpha\) is convergent iff its elements eventually get closer and closer to one another. More precisely, \[\forall k \exists n \forall m (|r_n – r_{n+m}| <_{\mathbb{Q}} 2^{-k}).\]

Two choice sequences \(\alpha=\langle r_i \rangle_i\) and \(\beta=\langle s_i \rangle_i\) coincide, in symbols, \(\alpha \simeq \beta\), when their own elements eventually get closer and closer to one another: \[\forall k \exists n \forall m (|r_{n+m} – s_{n+m}| <_{\mathbb{Q}} 2^{-k}).\]

We call a convergent choice sequence of rational numbers a real number generator. Now, let a real number be the equivalence class \(\{ \beta \mid \alpha \simeq \beta \}\) for some real number generator \(\alpha\). Finally, the species \(\mathbb{R}\) is simply defined as the species of all real numbers. For accessible accounts of the intuitionistic continuum, see (Dummett 1977, section 2.2) or (Posy 2020, section 2.2.2). It is worth emphasizing that, unlike in Bishop’s constructive mathematics, for example, intuitionistically the real numbers are not convergent sequences of rational numbers themselves. Real numbers remain treated as equivalence classes in intuitionism just as they are in classical mathematics. In this sense, intuitionism stays relatively closer to classical mathematics.

Spread

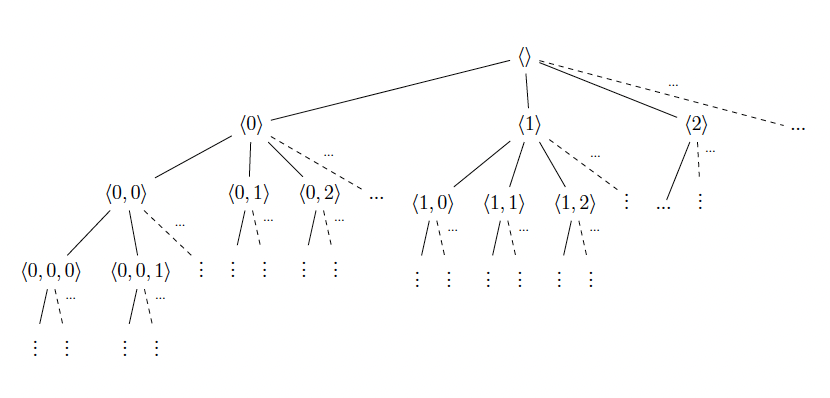

In fact, a species of choice sequences of rationals is what we call a spread. We can view a spread as a tree in which each node is a finite sequence but every path is infinite. As we mentioned earlier, a choice sequence can be identified with the paths of the tree. So spreads are essentially species of choice sequences sharing a law restriction. Although in the contemporary literature one often reduces the notion of spread to that of species, spreads were originally introduced by Brouwer as primitive mathematical objects. To be exact, a spread is defined by a spread law and a complementary law (Heyting 1956b, section 3.1.2). As shown below, the former serves to determine the admissible finite sequences of natural numbers, and the latter is used to map them to other mathematical objects.

The spread law classifies finite sequences into admissible and inadmissible. This law dictates the overall structure of the spread with an exhaustive account of all different admissible ways the finite sequences of natural numbers keep growing in time. Because it is exhaustive, it is possible to decide when a finite sequence is admissible or not, meaning that the excluded middle actually holds for finite sequences as far as the spread law is concerned. Moreover, the spread law always begins by including the empty sequence \(\langle\rangle\) as admissible and from then on proceeds by determining what its admissible extensions are. We say that the finite sequence \(\langle n_1, …, n_k, n \rangle\) is an extension of the finite sequence \(\langle n_1, …, n_k \rangle\). So, to sum up, every spread law has to satisfy the following four conditions:

1. the empty sequence is admissible;

2. either a finite sequence is admissible or not admissible;

3. at least one extension of an admissible sequence is admissible;

4. no extension of an inadmissible sequence is admissible.

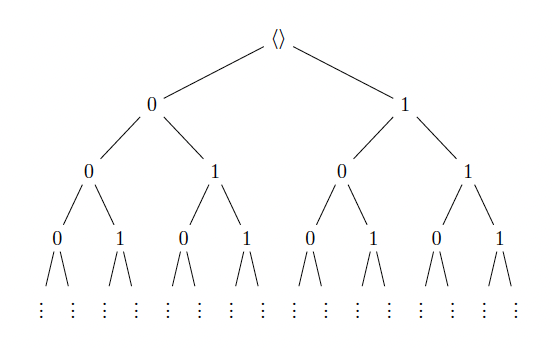

The complementary law assigns mathematical objects to the non-empty finite admissible sequences. In effect, it maps numeric choice sequences to choice sequences of elements of some species. For example, recall that in the construction of the continuum sketched above we work with choice sequences of rational numbers. Given that the species of real number generators is actually treated as a spread, as we already explained, in this case the complementary law assigns rational numbers to the non-empty finite sequences. Roughly, if the spread law provides an endoskeleton that supports the spread, the complementary law supplies the body tissue that reveals how it looks like. Spreads with only a spread law are called naked and those with a complementary law are called dressed. For example, the so-called “universal spread” is a naked spread of all finite sequences of natural numbers. It can be helpful to illustrate its tree structure diagrammatically. We start from the empty sequence as the root and then include its admissible extensions as its nodes: The species of real number generators mentioned above is an example of a dressed spread. But for a more concrete example, consider the spread of binary sequences (Posy 2020, p. 31). The spread law specifies that for every admissible sequence \(\langle b_1,…,b_k \rangle\), there are exactly two extensions \(\langle b_1,…,b_k,0\rangle\) and \(\langle b_1,…,b_k,1 \rangle\). The complementary law maps the sequence \(\langle b_1,…,b_k\rangle\) to its last binary digit \(b_k\). The spread can thus be visualized as follows:

The species of real number generators mentioned above is an example of a dressed spread. But for a more concrete example, consider the spread of binary sequences (Posy 2020, p. 31). The spread law specifies that for every admissible sequence \(\langle b_1,…,b_k \rangle\), there are exactly two extensions \(\langle b_1,…,b_k,0\rangle\) and \(\langle b_1,…,b_k,1 \rangle\). The complementary law maps the sequence \(\langle b_1,…,b_k\rangle\) to its last binary digit \(b_k\). The spread can thus be visualized as follows: Finally, what does it mean for a choice sequence \(\alpha\) to be an element of a spread \(M\)? We write \(\alpha \in M\) iff for every \(n\), the complementary law assigns \(\alpha(n)\) to an admissible sequence. In the simpler case of naked spreads, \(\alpha \in M\) iff for every \(n\), \(\overline{\alpha}(n)\) is admissible. It should be noted this treatment of membership is just a particular case of species membership.

Finally, what does it mean for a choice sequence \(\alpha\) to be an element of a spread \(M\)? We write \(\alpha \in M\) iff for every \(n\), the complementary law assigns \(\alpha(n)\) to an admissible sequence. In the simpler case of naked spreads, \(\alpha \in M\) iff for every \(n\), \(\overline{\alpha}(n)\) is admissible. It should be noted this treatment of membership is just a particular case of species membership.

Fan

Fans are finitary spreads. Informally speaking, the paths along the tree structure of a fan remain infinite, but the tree admits only finite branching. The spread of binary sequences illustrated above is an example of a fan. Note also that the binary fan has uncountably infinitely many infinite paths in the form of all sequences of zeros and ones. So despite the finite branching, fans need not even have a countable number of paths. We may characterize a fan as a spread that imposes an additional requirement that, for every admissible sequence, the spread law specifies that only a finite number of extensions is admissible.

One of the most important results in intuitionism is the so-called “fan theorem”. It can be understood as the intuitionistic counterpart of König’s lemma in classical graph theory, which states that if there is no finite upper bound to the paths of a finitely branching tree then the tree has at least one infinite path. Classically, its contrapositive thus states that if every path in a finitely branching tree is finite then there exists a longest finite path. That is precisely what the fan theorem says in intuitionistic mathematics, except that “there exists” must be interpreted constructively and the context is transposed to fans. One difficulty is that, strictly speaking, the intuitionist cannot have a finite path in a fan, since every path in a spread is identified with a choice sequence and is thus infinite. To make sense of the idea that a path terminates in another way, Brouwer introduced the concept of a bar. Simply put, a bar \(R\) is a species of “nodes” such that each path in a spread \(M\) is intersected. To be exact, \(R\) is a bar if every choice sequence in \(M\) has some initial segment of some length in \(R\): \[\forall \alpha \in M \exists n \overline{\alpha}(n) \in R.\]

Since the bar associates every choice sequence with a number, it in essence simulates some kind of oracle device telling us the lengths where the paths terminate. This captures the intuition that a finitely branching tree is finite. That is what a barred fan is. Now, in this intuitionistic terminology, we can express the idea that the fan has a finite path, namely, the consequent of König’s lemma, if we can determine a length such that every choice sequence in \(M\) has initial segment no longer than this length in \(R\): \[\exists m \forall \alpha \in M \exists n (n \leq m \land \overline{\alpha}(n) \in R).\]

We are now in a position to state the fan theorem:

Theorem 1 (Fan theorem). Let \(M\) be a fan and \(R\) be a species of finite sequences. If every \(\alpha \in M\) has an initial segment of length \(n\) in \(R\), then there exists a longest length \(m\) such that every \(\alpha \in M\) has an initial segment no longer than \(m\) in \(R\):

\[

\tag{FT}

(\forall \alpha \in M \; \exists n \; \overline{\alpha}(n) \in R)

\;\to\;

(\exists m \; \forall \alpha \in M \; \exists n \; (n \leq m \;\land\; \overline{\alpha}(n) \in R)).

\]

But how is the fan theorem proved? The classical proof of König’s lemma makes use of an intuitionistically invalid inductive argument to show the existence of \(m\) (Dummett 1977, p. 51). The intuitionist must therefore appeal to a different argument.

The proof of the fan theorem relies on an original argument known as the principle of bar induction. It can be stated without loss of generality for the universal spread \(M\). Let \(A\) be a subspecies of admissible sequences of \(M\). Call \(A\) *upward hereditary* if whenever every extension by one element of a finite sequence is in \(A\), then so is the finite sequence itself.

In the unrestricted form conceived by Brouwer, the principle of bar induction states that, if \(R\) is a bar, \(R\) is a subspecies of \(A\), and \(A\) is upward hereditary, then the empty sequence belongs to \(A\):

\[

\tag{BI}

\bigl(\forall \alpha \in M \; \exists n \; \overline{\alpha}(n) \in R \; \land\;\\

\forall u \,(u \in R \lor u \notin R) \;\land\; \forall u \,(u \in R \to u \in A) \; \land\;\\

\forall u \,(\forall n \,(u \cdot \langle n \rangle \in A) \to u \in A)\bigr) \;\to\; \langle \rangle \in A.

\]

Here \(u \cdot \langle n \rangle\) denotes the extension of a finite sequence \(u\) by one element \(n\). It helps to think of \(A\) as the species of those finite sequences for which we can find the length required by the consequent of the fan theorem. Indeed, the proof proceeds by instantiating \(A\) with such a species \(\{ u \mid \exists m \forall \alpha \in M \exists n (n < m \land \overline{\alpha}(n) \in R) \land \exists k \; u = \alpha(k) \}\).

Another key result in intuitionistic mathematics goes by the name of the “bar theorem”. The fan theorem can be easily confused with this theorem because it is also a result about bars. In fact, the bar theorem is simply the statement that bar induction holds. It should be noted that in bar induction the restriction that the spread must be finitary is dropped. So bar induction is maintained not just for fans but spreads in general. Brouwer originally derived the fan theorem using the principle of bar induction as a corollary of the bar theorem. The proof of the bar theorem is presented in three different articles (Brouwer 1924, 1927, 1954). His proofs have been extensively studied because they inaugurate a proof-theoretic method of analysis of the structure of canonical proofs. The bar theorem has even found applications in repairing Gentzen’s original proof of the consistency of arithmetic. But a careful study would be outside the scope of this introductory article. The reader is referred to Dummett (1977, section 3.4), Martino and Giaretta (1981), and Sundholm and van Atten (2008) for more on Brouwer’s proof and to Tait (2015) for connections with Gentzen’s original consistency proof.

It should be emphasized, however, that the principle (BI) originally formulated by Brouwer turns out to be false intuitionistically (Kleene and Vesley 1965, section 7.14). In this unrestricted form, bar induction implies a quantified version of the law of excluded middle and thus, as it can be inferred from 1.2.1.1, it must be inconsistent with the continuity principle. To fix this, Kleene proposes that we add an additional requirement that \(R\) is decidable:

\[

\tag{BI$_D$}

\bigl(\forall \alpha \in M \; \exists n \; \overline{\alpha}(n) \in R \; \land\; \\ \forall u \,(u \in R \lor u \notin R) \;\land\; \\ \forall u \,(u \in R \to u \in A) \;\land\;\\ \forall u \,(\forall n \,(u \cdot \langle n \rangle \in A) \to u \in A)\bigr)

\;\to\; \langle \rangle \in A.

\]

(Van Atten 2004, section 4.3) argues that the decidability condition is implicit in Brouwer’s earlier proofs from 1924 and 1927, though not in the 1954 proof. Another intuitionistically valid formulation introduces a requirement of monotonicity. \(R\) is monotonic if the fact that \(u \in R\) and \(v\) is an extension of \(u\), \(u \preceq v\), implies that \(v \in R\):

\[

\tag{BI$_M$}

\bigl(\forall \alpha \in M \; \exists n \overline{\alpha}(n) \in R \land\ \\

\forall u (u \in R \land u \preceq v \to v \in R) \land\ \\

\forall u (u \in R \to u \in A) \land\ \\

\forall u (\forall n (u \cdot \langle n \rangle \in A) \to u \in A)\bigr) \to \langle \rangle \in A.

\]

Brouwer’s “proof” of the bar theorem is not actually a proof. Surely, it must be erroneous since the unrestricted form of bar induction used does not hold intuitionistically. But even if we correctly derive the bar theorem from decidable or monotonic bar induction, these principles are no less in need of justification than the statement to be proved. Still, despite its mathematical shortcomings, Brouwer’s argument remains philosophically significant in that it serves to shed light on the intuitive content of the bar theorem. Before concluding this discussion of Brouwer’s views, it should be remarked that the fan and bar theorems were primarily motivated by him as tools to prove the uniform continuity theorem, which states that every total real function is uniformly continuous. This is an even stronger counterexample than the continuity result mentioned in 1.2.1. Finally, we note that the fan theorem is incompatible with Church’s thesis (Dummett 1977, p. 53).

c. The Creating Subject

Intuitionism is the product of the activity of the creating subject, an idealized mind carrying out constructions and experiencing truths at discrete stages of time. (Brouwer 1948a) starts introducing in print arguments relying on the creating subject to construct weak and strong counterexamples to classical principles based on the solvability of open problems. Such arguments are ultimately grounded in Brouwer’s conception of truth, according to which a proposition is true if it has been experienced by the creating subject:

[…] truth is only in reality i.e. in the present and past experiences of consciousness. Amongst these are things, qualities of things, emotions, rules (state rules, cooperation rules, game rules) and deeds (material deeds, deeds of thought, mathematical deeds). But expected experiences, and experiences attributed to others are true only as anticipations and hypotheses; in their contents there is no truth (Brouwer 1948b, p. 1243).

At this stage [of introspection of a mental construction] the question whether a meaningful mathematical assertion is correct or incorrect, is freed of any recourse to forces independent of the thinking subject (such as the external world, mutual understanding, or axioms which are not inner experience) and becomes exclusively a matter of individual consciousness of the subject. Correctness of an assertion then has no other meaning than that its content has in fact appeared in the consciousness of the subject (van Stigt 1990, p. 450).

[…] in mathematics no truths could be recognized which had not been experienced […] (Brouwer 1955, p. 114).

There has been much debate about the exact nature of the creating subject. Brouwer is frequently accused of psychologism, subjectivism, or even solipsism. Placek (1999, section 2.4.1) defends Brouwer against the charges of psychologism and subjectivism by maintaining that the creating subject is a transcendental subject in Kant’s sense. The transcendence is hinted at in passages such as the above, where Brouwer stresses that all our physical and psychological limitations as human subjects are abstracted away, such as our finite lifespan, imperfect memory, mental state, mathematical proficiency. Although Brouwer does argue against the plurality of minds (Brouwer 1948b, pp. 1239-1240), Placek notes that there is still some room left for intersubjectivity, which allows for the possibility of communication with other minds equally equipped with all the cognitive structure assumed by Brouwer.

There is also some dispute as to whether the transcendental status of Brouwer’s creating subject is better understood from Kant’s or Husserl’s perspective. Perhaps because of the way Brouwer himself explicitly acknowledges his debt to Kant, the received view is the Kantian interpretation assumed by (Placek 1999). Similarities between Brouwer and Kant in the context of their transcendental philosophies are most systematically drawn by Posy (1974, 1991, 1998). At the same time, however, there are other similarities between Brouwer and Husserl that are just as difficult to ignore. Drawing from the phenomenology of inner-time awareness, van Atten (2004, section 6.2) argues that Brouwer’s creating subject is best analyzed using Husserl’s phenomenology. Further connections between Brouwer’s intuitionism and Husserl’s phenomenology have been explored especially by Tieszen (1989, 1995, 2008) and van Atten (2006, 2017, 2024). 2.2 shows that this phenomenological interpretation of intuitionism is originated by the meaning explanations advanced by Heyting in terms of fulfillments of intentions.

Creating Subject Argument:

It is time to return to the creating subject arguments. Brouwer realized that the way the creating subject experiences truths about open problems could be used to define choice sequences and generate counterexamples to emphasize the elements of indeterminacy in intuitionistic analysis. To see how this can be done, it might be instructive to examine a simple argument used by Brouwer as a weak counterexample to \(\forall r \in \mathbb{R}(r \neq 0 \to r > 0 \lor r < 0)\) (Brouwer 1948a, p. 322). We say that a proposition \(A\) is testable if the instance of the weak law of excluded middle \(\neg A \lor \neg\neg A\) holds. Given a proposition \(A\) not known to be testable, Brouwer maintains that the creating subject can construct a choice sequence \(\alpha\) of rationals by making the following choices:

- if during the choice of \(\alpha(n)\) the creating subject has neither experienced the truth of \(A\) nor its absurdity then choose \(\alpha(n) = 0\);

- if as soon as between the choice of \(\alpha(k-1)\) and \(\alpha(k)\), the creating subject has

experienced the truth of \(A\) then choose \(\alpha(k+n) = 2^{-k}\) for every \(n\); - if as soon as between the choice of \(\alpha(k-1)\) and \(\alpha(k)\), the creating subject has

experienced the absurdity of \(A\) then choose \(\alpha(k+n) = -2^{-k}\) for every \(n\).

Let us introduce some notation to make this definition a bit more mathematically precise. Brouwer’s tenet that “there are no non-experienced truths” can be understood as saying that, if a proposition \(A\) is true, then it is not possible that there is no stage at which the creating subject is going to experience the truth of \(A\). In the presence of a special notation \(\Box_n A\) to express that “the creating subject has experienced the truth of \(A\) at stage \(n\)”, then this fundamental tenet can be put into symbolic notation as:

\[A \to \neg

\neg \exists n \Box_n A.\]

The above definition can then be more rigorously stated as:

\[

\alpha(n) =

\begin{cases}

0 & \text{if } \neg \Box_n (A \lor \neg A) \\[6pt]

2^{-k} & \text{for all } n \geq k \text{ if } \Box_k A \text{ and } \neg \Box_{k-1}(A \lor \neg A) \\[6pt]

-2^{-k} & \text{for all } n \geq k \text{ if } \Box_k \neg A \text{ and } \neg \Box_{k-1}(A \lor \neg A).

\end{cases}

\]

\(\alpha\) is convergent and thus a real-number generator. Yet, the real number \(r\) generated by \(\alpha\) cannot be \(0\) because that would lead to a contradiction. If that were the case, \(\alpha(n)=0\) for all \(n\), meaning that \(\forall n \neg \Box_n (A \lor \neg A)\). Intuitionistically, the De Morgan law \((\forall x \phi(x)) \to (\neg \exists x \neg \phi(x))\) and contraposition \((\phi \to \psi) \to (\neg \psi \to \neg\phi)\) are valid schemes. See the appendix for more information. The contradiction \(\neg A \land \neg\neg A\) follows from the contrapositive of Brouwer’s tenet, \(\neg \exists n \Box_n (A \lor \neg A) \to \neg (A \lor \neg A)\). This shows that \(r \neq 0\). Yet, if \(r > 0\), there is a \(k\) such that \(\alpha(n) = 2^{-k}\) and thus the truth of \(A\) has been experienced, contradicting our assumption that \(A\) is not known to be testable. Since the same can be said mutatis mutandis for \(r < 0\), we have established that \(r < 0 \lor r > 0\) does not hold. For an overview of this and other examples given by Brouwer, see (van Atten 2018).

Creating subject arguments tend to be seen as a controversial aspect of intuitionism because it is not clear how they qualify as mathematical arguments (Heyting 1956b section 8.12.1). In spite of the doubts surrounding them, they have been studied in the literature and different formalizations have been offered to make precise the assumptions underlying them. We conclude this section by presenting the two most influential proposals:

Kripke’s Schema:

\[\tag{KS} \label{wks}

\exists \alpha ((\neg A \leftrightarrow \forall n \alpha(n)=0)

\land (\exists n \alpha(n)\neq 0 \to A)).\]

This schema was proposed by Kripke in a letter to Kreisel around 1965 (Kripke 2019, fn. 8). This letter led Kreisel to formulate the theory of the creating subject to be seen soon. The schema is intended to describe the generation of a choice sequence \(\alpha\) out of the truth or absurdity of a proposition \(A\) experienced by the creative subject. Though Kripke originally formulated it in what is known as its weak form, there is a stronger and simpler form:

\[\tag{KS+} \label{sks} \exists \alpha (A \leftrightarrow \exists n \alpha(n)=1).\]

Van Atten (2018) stresses that both schemes are present in Brouwer’s published work.

The Theory of the Creating Subject:

\[

\begin{align*}

\tag{CS1} & \forall n (\Box_n A \lor \neg \Box_n A) \\

\tag{CS2} & \forall n (\Box_n A \to \Box_{n+m} A) \\

\tag{CS3} & \forall n (\Box_n A \to A) \\

\tag{CS4} & A \to \neg \neg \exists n \, \Box_n A.

\end{align*}

\]

The theory of the creating subject was originally proposed by Kreisel (1967, secton 3) and subsequently refined by Troelstra (1969, section 16). In their expositions they employ a turnstile notation to represent the creating subject and omit the universal quantifiers. The modal notation used here is introduced by Troelstra and van Dalen (1988, p. 236). The four axioms above emphasize that the creating subject continuously performs their mental activities one after another at stages of time. (CS1) states that \(\Box_n A\) is decidable at every stage \(n\), for the creating subject either experiences a truth or not. (CS2) expresses that truths experienced in past stages are never forgotten at subsequent stages. (CS3) encapsulates the plausible principle that experienced truths are indeed truths. At any stage \(n\), if the creating subject has experienced the truth of \(A\), then \(A\) is true. (CS4) expresses the already familiar tenet discussed before. Importantly, (KS) is derivable from these four axioms. It can be derived with the strengthening of (CS4) proposed by Troelstra (1969, pp. 95-96): \[\tag{CS4+} \label{cs4plus} A \leftrightarrow \exists n \Box_n A.\]

For additional readings the reader is referred to (Posy 2020, sections 2.2.3 and 3.2.4).

2. Heyting

Although Brouwer downplays the roles of logic and language in his intuitionism, the development of intuitionistic logic by his student Arend Heyting and others has ironically made intuitionism more accessible and generated a growing interest. Historically, intuitionistic logic came into being when the Dutch Mathematics Society held a contest involving the formalization of intuitionistic logic and mathematics, and developed the first full axiomatization of intuitionistic first-order logic by isolating the set of intuitionistically acceptable axioms of Principia Mathematica. Heyting begins the undertaking with the following remark that echoes Brouwer’s attitude about language: