The Definition of Art

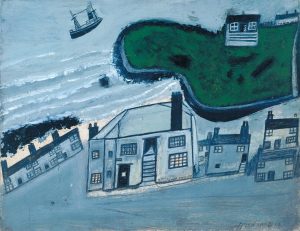

A definition of art attempts to spell out what the word “art” means. In everyday life, we sometimes debate whether something qualifies as art: Can video games be considered artworks? Should my 6-year-old painting belong to the same category as Wallis’ Hold House Port Mear Square Island (see picture)? Is the flamboyant Christmas tree at the mall fundamentally different from a Louvre sculpture? Is a banana taped to a wall really art? Definitions of art in analytic philosophy typically answer these questions by proposing necessary and sufficient conditions for an entity x to fall under the category of art.

Defining art is distinct from the ontological question of what kind of entities artworks are (for example, material objects, mental entities, abstractions, universals…). We do not, for example, need to know whether a novel and a sculpture have a distinct ontological status to decide whether they can be called “artworks.”

Definitions of art can be classified into six families. (1) classical views hold that all artworks share certain characteristics that are recognizable within the works themselves (that is, internal properties), such as imitating nature (mimesis), representing and arousing emotions (expressivism), or having a notable form (formalism). A modified version of this last option is enjoying a revival in 21st century philosophy, where art is said (2) to have been produced with the aim of instantiating aesthetic properties (functionalism). Classical definitions initially met with negative reactions, so much so that in the mid-twentieth century, some philosophers advocated (3) skepticism about the possibility of defining art while others critiqued the bias of the current definitions. Taking up the challenge laid out by theses critics, (4) a fourth family of approaches defines art in terms of the relations that artworks enjoy with certain institutions (institutionalism) or historical practices (historicism). (5) A fifth family of approaches proposes to analyze art by focusing on the specific art forms—music, cinema, painting, and so one—rather than on art in general (determinable-determinate definitions). (6) A last family claims that “art” requires to be defined by a disjunctive list of traits, with a few borrowed from classical and relational approaches (disjunctivism).

Table of Contents

- Some Constraints for a Definition of Art

- Classical Definitions of Art

- The Skeptical Reaction

- Relational Definitions

- Feminist Aesthetics, Black Aesthetics, and Anti-Discriminatory Approaches

- Functionalist Definitions

- Determinable-Determinate Definitions

- Disjunctive Definitions

- Conclusion

- References and Further Reading

1. Some Constraints for a Definition of Art

The concept expressed by the word “art” may have a relatively recent, and geographically specific, origin. According to some, the semantic distinction between “art” and “crafts” emerged in Europe in the 18th century with the notion of “fine arts,” which includes music, sculpture, painting, and poetry (Kivy 1997, Chapter 1). Indeed, terms such as ars in Latin and tekhnê in Ancient Greek bear some relation to today’s concept of art but they also referred to trades or techniques such as carpentry or blacksmithing. In the Middle Ages, “liberal arts” included things such as mathematics and astronomy, not only crafts. This old meaning of “art” survives in expressions such as “the art of…”—for example, the art of opening a bottle of beer. Similar remarks can be made for related non-Western notions, such as the Hindu notion of “kala” (कला), which involves sixty-four practices, not all of which we would call artistic (Ganguly 1962). “Art” nowadays is more likely understood to mean something more restricted than these traditional meanings.

These differences in terminology do not mean that past or non-Western cultures don’t make art. On the contrary, making art is arguably a typical human activity (Dutton 2006). Moreover, the fact that a culture does not have a word co-referent with “art” does not mean that it does not have the concept of art or, at least, a concept that largely overlaps with it—see Porter (2009) against the idea that the concept of art has emerged only with the notion of “fine arts.” The following definitions of art are thus intended to apply to the practices and productions from all cultures, whether or not they possess a specific term for the concept.

Defining art typically relies on conceptual analysis. Philosophers aim to provide criteria that capture what people mean in everyday life when they talk and think about art while, at the same time, avoiding conceptual inconsistencies. This methodology goes hand in hand with a certain number of criteria that any definition of art must respect.

a. Criteria

Despite the immense diversity of definitions of art, philosophers usually agree on a set of minimum criteria that a good definition must meet in order to respect both folk and specialist uses of the term (in art history, art criticism, aesthetics…) while avoiding mere trivialities (Lamarque 2010). Three classes of criteria can be distinguished: those specifying what a definition must include, those that specify what it must exclude, and those the cases that a good definition must take into account.

i. What a Definition of Art Should Include

[i] Art of a mediocre quality.

[ii] Art produced by people who do not possess the concept of art.

[iii] Avant-garde, future, or possible art (for example, extraterrestrial art).

Criterion [i] touches on what might be called the descriptive project of an art definition. As noted by Dickie (1969), we sometimes use the word “art” descriptively—“The archeologists found tools, clothes, and artworks”—and sometimes evaluatively—“Wow, mom, your couscous is a real artwork!” Dickie points out that, in the past, the descriptive and evaluative (or prescriptive) uses of the term have often been confused. Introducing mediocre art as a criterion excludes the prescriptive or evaluative use. One reason for this is the practice of folk and professional criticism: we may talk of “bad plays”, “insipid books”, or “kitsch songs”, without denying that they are artworks. Doing so also avoids confusing personal or cultural preferences with the essence of art.

Criterion [ii] avoids excluding art produced before the 18th century, non-Western art, as well as the art brut (or outsider art) produced by people whose education or cognitive conditions make it unlikely that they are familiar with the concept of art. A good definition, therefore, does not require the artist to possess the contemporary, Western notion of art to produce artworks.

Criterion [iii] implies that a good definition must do more than designate a set of entities; it must be able to play an explanatory role and make fruitful predictions (Gaut 2000; Lopes 2014). Considering the upheaval that traditional art has undergone in the twentieth century with the emergence of cinema, conceptual art, and so on, this criterion takes on particular importance: any definition that fails to be predictive is doomed to soon be outdated.

ii. What a Definition of Art Should Exclude

[iv] Purely natural objects

[v] What purports to be art but has failed completely

[vi] Non-artistic artifacts (including those with an aesthetic function)

One of the few consensuses in aesthetics is that an artwork is an artifact [iv]—an object intentionally created for a certain purpose. Although a tree or the feathers of a peacock possess undeniable aesthetic qualities, they are not called artworks in the descriptive sense. Note that the criterion [iv], as formulated, does not necessarily exclude productions by Artificial Intelligence even if one denies that AI models are genuine creators of artifacts (see Mikalonytė and Kneer 2022 for empirical explorations of who are considered as the creators of AI-generated art).

A “minimal achievement” is also required for an object to be an artwork [v]. Thus, if Sandrine attempts to play a violin sonata without ever having touched an instrument in her life, she risks failing to produce something identifiable as an artwork. It’s not that she will have played a “bad piece,” but rather that she will have failed to produce a piece of music at all.

Finally, [vi] a good definition of art must also exclude certain artifacts—and this, despite their aesthetic qualities. Even if the maker of a shoelace, a nail, or an alarm bell may have intentionally endowed them with aesthetic properties, this does not seem sufficient to qualify them as art. It is possible to create non-artistic aesthetic artifacts. It is also possible to create shoelaces that are artworks. However, this is—and should—not be the case for most of them.

iii. What a Definition of Art Should Account For

[vii] Borderline cases

A good definition must be able to reflect the fact [vii] that there are many borderline cases, cases where it is not clear whether the concept applies—such as children’s drawings, lullabies, paintings produced by animals, Christmas trees, rituals, jokes, YouTube playthroughs, drafts… A good definition might exclude or include these cases or even account for their tricky nature; in any case, it should not remain silent about them. After all, these are the cases that may most often raise the question “What is the meaning of “art?”

Most contemporary definitions respect these criteria or consider the difficulties posed by some of them. This is less the case for definitions dating from before the second half of the twentieth century.

2. Classical Definitions of Art

Although the focus here is on contemporary definitions of art within the analytic philosophy tradition, it is worth doing a quick tour of the definitions that have prevailed in the West before and what problems they face.

a. Mimesis

i. The Ancients

Although we will focus on contemporary definitions of art within the analytic philosophy tradition, it is worth doing a quick tour of the definitions that have prevailed in the West before and what problems they face.

Plato, Aristotle, and their contemporaries grouped most of what is called “art” today under the heading of “mimesis”. In the Republic or the Poetics (for example, 1447a14-15), the focus is on works that would undeniably be considered artworks today: the poems of Homer, the sculptures of Phidias, works of music, architecture, painting, and so on.

Mimesis is an imitation or representation of the natural, in the sense that artists depict, represent, or copy movements, forms, emotions, and concepts found in nature, human beings, and even gods. The aim is not to achieve hyper-realism (à la Duane Hanson) or naturalism (à la Emile Zola), but to represent possible situations or even universals.

Perhaps surprisingly, even purely instrumental music was considered to be imitative. Beyond the representation of birdsong or the human voice, Aristotle among others believed that music could resemble the movements of the soul, and thus imitate the emotions, moods, and even character traits (vices and virtues) of sentient beings (see, for example, Aristotle’s Politics, 1340a). From that point of view, there is no such thing as non-representational art.

ii. The Moderns

The idea of mimetic art was hegemonic for around two millennia. Witness Charles Batteux who, in Les Beaux-arts réduits à un même principe (1746), popularized the concept of “fine arts” (Beaux-arts) and defended that the essence of these is their ability to represent. In particular, he sees them as an assemblage of rules for imitating what is Beautiful in Nature.

It is interesting to note that when Batteux wrote these lines, he was faced with the unprecedented development of music whose aim was not to imitate anything, as the genres of concerto, ricercare, and sonata were emerging. Batteux is opposed to the idea of non-representational music or dance, which, in his view, “goes astray” (“s’égarer”) (Batteux 1746, 1, chap. 2, §§14-15). Rousseau’s remarks (for example, 1753) on music—and, more particularly, on sonatas—also reflect the conception of art as mimetic among 18th-century thinkers.

iii. The Limits of the Mimesis Theory

The first problem with this theory is that imitation (mimesis) is not a necessary condition for the definition of art. Today, it seems clear that abstract art—that is, works that are not representational—is possible. Just think about Yayoi Kusama’s infinity nets. Thus, mimesis theorists seem to be violating the criterion [iii]: a definition of art must be able to include avant-garde, future, or possible art. Besides, Batteux’s assertion that non-representational music is defective seems to be a case where the descriptive and the prescriptive views of art are conflated. In the same vein, the notion of fine arts has also been vigorously criticized by feminist philosophers as it tends to exclude many works from the realm of genuine arts, including art practices traditionally associated with women, such as embroideries or quilts.

Nevertheless, a more charitable reading of the mimesis theory would see its criterion as going beyond obviously figurative representations. For example, Philippe Schlenker (2017) and Roger Scruton (1999) argue that all music, however abstract, represents or is a metaphor for real-world events, such as spatial movements or emotional changes. This idea captures the fact that, when listening to purely instrumental music, it’s easy to imagine a whole host of shapes or situations, sometimes cheerful and lively, sometimes melancholic and dark, that correspond more or less to the music’s rhythms, melodies, and harmony. Animations illustrating instrumental music also come to mind, as in Walt Disney’s Fantasia or Oskar Fischinger’s Optical Poem. In this broad sense, all art, even if it is not intended to be representational, can be seen as mimetic.

This attempt to save the mimesis theory can be criticized—see, for example, Zangwill (2010) on Scruton. However, even if one dismisses these critics, there seems to be a fatal problem: mimesis is in any case not a sufficient condition. For example, it cannot exclude non-artistic artifacts (criterion [vi]), nor can it properly account for borderline cases (criterion [vii]). Indeed, objects such as passports, souvenir key rings, or any sentence endowed with meaning are mimetic without falling into the category of art. This theory is therefore unsatisfactory.

b. Expressivism

Expressivist theories of art have been championed by many Romantic and post-Romantic philosophers, including Leo Tolstoy, Robin Collingwood, Benedetto Croce, John Dewey, and Suzanne Langer. Let us start with the first, often cited as a paradigmatic representative.

i. Tolstoy

The hegemony of the mimesis theory was gradually replaced by expressivist theories during the (late) Romantic period. Tolstoy is a flamboyant example. In the 2023 edition of What is Art (1898), he defends the following thesis:

To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced, and having evoked it in oneself, then, by means of movements, lines, colors, sounds, or forms expressed in words, so to transmit that feeling that others may experience the same feeling—this is the activity of art (Tolstoy 1898 [2023], 52).

Tolstoy’s expressivist view is particularly strong in that it implies, on the one hand, that the artist experiences a feeling and, on the other, that this feeling is evoked in the audience. Other versions of the expressivist thesis require only one or the other of these conditions, but for Tolstoy, until the audience feels what the artist feels, there is no art. Note also that, in an expressivist approach, communicating both positive and negative emotions can lead to a successful work. Thus, Francis Bacon’s tortured works are expressivist masterpieces since they communicate the author’s near-suicidal state (see Freeland, 2002, Chap.6).

At first glance, expressivism is seductive: if we go to the movies, read a novel, or listen to a love song, is it not to undergo certain emotions? A second look, however, reveals an obvious problem: the existence of “cold” art. There seem to exist artworks whose purpose is not to communicate any affect. We can think of modern or contemporary cases, such as Malevich’s White on White or Warhol’s Empire—an 8-hour-long static shot of the Empire State Building. But we can also think of more traditional artworks, such as Albrecht Dürer’s Hare (see picture), a masterpiece of observation from nature that does not clearly meet Tolstoy’s expressivist criteria.

ii. Collingwood and Langer

A less demanding expressivist theory is advocated by Collingwood and refined by Langer. Unlike Tolstoy, Collingwood’s theory does not require the audience to feel anything: it’s enough that the artist has felt certain “emotions” and expresses them. Langer, for her part, argues that the artist does not need to feel an emotion, but she should be able to imagine it—and thus to have a certain knowledge of that emotion (see the IEP article on Susanne K. Langer).

According to one charitable interpretation, by “emotions” Collingwood means something similar to Susanne Langer’s notion of feelings:

The word ’feeling’ must be taken here in its broadest sense, meaning everything that can be felt, from physical sensation, pain and comfort, excitement and repose, to the most complex emotions, intellectual tensions, or the steady feeling-tones of a conscious human life (1957, p. 15).

So, a broad category of mental states can be qualified as feelings, including being struck by a contrast of colors or a combination of sounds (Wiltsher 2018).

By “expression”, Collingwood means an exercise in “transmuting” emotion (in the broad sense) into a medium that makes it shareable, which would require an exercise of the imagination (Wiltsher 2018, 771-8). Langer’s theory of art is similar, she emphasizes that expressing feelings requires the use of a symbolic form to transmit what the artist grasps about the value that an event has for them (Langer 1967). In that sense, it’s possible that Dürer could have expressed the elements that struck him in the hare he depicts.

iii. Limits of Expressivism

Although Collingwood and Langer’s theories are rich and sophisticated, they seem to run up against the same kind of objections as Tolstoy’s view, since it requires that the artist has actually experienced what is supposed to be expressed in the work. However, it’s doubtful that every artwork meets this criterion, and it is possible that many do not. An example is provided in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Philosophy of Composition (1846). He explains that he wrote The Raven purely procedurally, “with the precision and rigorous logic of a mathematical problem” (idem, 349), without reference to anything like feelings or emotions. Of course, Poe must have gone through certain mental states and feelings when writing this famous poem, but the point is that it is arguably not necessary that he had a feeling that he then expressed in order to create this artwork.

Even if one remains convinced that Poe and any other artist must in fact express feelings in the artworks they create, there is another problem with an expressivist theory which, as in the mimesis case, seems insurmountable: The expression of feelings is not a sufficient condition for art. Love letters, insults, emoticons, and a host of other human productions have an expressive purpose, sometimes brilliantly achieved, but this does not make them artworks. Expressivists, like mimesis theorists, seem unable to accommodate criteria [vi] and [vii]: excluding non-artistic artifacts and accounting for borderline cases (Lüdeking 1988, Chap.1).

c. Formalism

After the Romantic period and the apex of expressivism, a new, more objectivist trend emerged, closer to the spirit of its contemporary abstract artists. Instead of focusing on the artist’s feelings, formalism attempts to define art by concentrating on formal aesthetic properties—that is, aesthetic properties that are internal to the object and accessible by direct sensation, such as the aesthetic properties of colors, sounds, or movements (see the IEP article on Aesthetic Formalism). This (quasi-)objectivist approach is infused by Kant’s view on beauty (Freeland 2002, 15)—see Immanuel Kant: Aesthetics.

Note that formalism has affinities with aesthetic perceptualism, the view that any aesthetic property is a formal aesthetic property (Shelley 2003). However, moderate formalism does not imply aesthetic perceptualism (Zangwill 2000): A formalist may accept that artworks possess non-formal relevant properties—for example, originality, expressiveness, or aesthetic properties that depend on symbols (for example, in a poem). Nevertheless, for the formalist, these properties do not define art. This is developed in section 6.

i. Clive Bell

One of the leading figures of formalism is Clive Bell (1914)—and, later Harold Osborne (1952). According to formalism, the essence of visual art is to possess a “significant form,” which is a combination of lines and colors that are aesthetically moving. This is how he introduces this idea:

There must be some one quality without which a work of art cannot exist; possessing which, in the least degree, no work is altogether worthless. What is this quality? What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to Sta. Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl, Chinese carpets, Giotto’s frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cézanne? Only one answer seems possible–significant form (Bell 1914, 22).

A clear advantage of formalism over expressivism is that it allows us to account for what is herein defined as “cold art”. Malevich’s White on White, Warhol’s Empire, and Dürer’s Hare do not necessarily trigger strong emotions, but the arrangement of colors and lines in these works nevertheless possess notable aesthetic properties. Similarly, Edgar Allan Poe’s poem may not express the author’s feelings, but its formal properties are noteworthy. Another notable advantage of formalism—especially over the mimesis theory—is that it readily accounts for non-representational art, contemporary as well as ancient or non-Western. Indeed, Bell was particularly sensitive to the emergence of abstract art among his contemporaries.

ii. Limits of Formalism

The first problem for formalism is that there seem to be artworks that lack formal aesthetic properties—particularly among conceptual art. The prototypical example is Duchamp’s famous Fountain (Fontaine). While some might argue that the urinal used by Duchamp possesses certain formal aesthetic properties—its immaculate whiteness or its generous curves—these are irrelevant to identifying the artwork that is Fountain (Binkley 1977). Duchamp specifically chose an object which, in his opinion, was devoid of aesthetic qualities, and, in general, his ready-made can be composed of any everyday object selected by the author (a shovel, a bottle-holder…). Similarly, a performance like Joseph Beuys’ I Like America and America Likes Me seems devoid of any formal aesthetic properties—Beuys’ performance consisted mainly of being locked in a cage with a coyote for three days. Formalism thus is threatened by criterion [iii]: there are avant-garde or possible art forms that go beyond formalism. It should be noted, however, that Zangwill offers possible answers to these counterexamples, which are discussed in section 6.a..

A second problem for formalism is that the possession of formal aesthetic properties is not sufficient to be art. Again, the problem concerns criteria [vi] and [vii]: excluding non-artistic artifacts and accounting for borderline cases. As noted above (1.c.), there are a whole host of artifacts that are elegant, pretty, catchy, and so one. in virtue of their perceptual properties but that are not artworks. Formalism seems unable to answer this objection (we will see how neo-formalism tries to avoid it in section 6).

3. The Skeptical Reaction

From the 1950s onwards, a general tendency against attempts to define art emerged among analytic philosophers. The main classical theories were being challenged by avant-garde art which constantly pushed back the boundaries of the concept. At the same time, a general suspicion towards definitions employing necessary and sufficient conditions emerged under the influence of Wittgenstein. In response, philosophers such as Margaret MacDonald and Morris Weitz adopted a radical attitude: they argued that art simply cannot be defined.

a. Anti-Essentialist Approaches

Wittgenstein (1953, §§ 66-67) famously endorses a form of skepticism with regard to the definition of games in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions. He postulates that there are only non-systematic features shared only by some sub-categories of the super-category ’games’—for example, one can win at football and chess…—from which a general impression of similarity among all members emerges, which he calls “a family resemblance”.

Margaret MacDonald, a student of Wittgenstein, is historically the first to take up this argument for art (see Whiting 2022). In her pioneer work, she argues that artworks should be compared “to a family having different branches rather than to a class united by common properties which can be expressed in a simple and comprehensive definition.” (MacDonald 1952, 206–207) In other words: art has no essence and cannot be defined with sufficient and necessary conditions.

Several philosophers came to the same conclusion in the years following MacDonald’s publications. Among them, Morris Weitz’s (1956) argument is the most influential. It claims that the sub-categories of artworks (such as novel, sonata, sculpture…) are concepts that can be described as “open” in the sense that one can always modify their intensions, as their extensions grow due to artistic innovations. Since all art sub-categories are open, the general “art” category should be open too. For instance: is Finnegans Wake a novel (or something brand new)? Is Les Années a novel (or a memoir)? To include these works in the “novel” category, the definition of the term needs to be revised. The same applies to all the other sub-categories of artworks: they need to be revised as avant-garde art progresses. So, since the sub-categories of art cannot be closed, we cannot provide a “closed” definition of art with necessary and sufficient conditions. Weitz moreover thinks that art should not be defined since, in his view, this hinders artists’ creativity.

The view of art as family resemblances is neither a definition nor even a characterization of art—it’s essentially a negative theory. Indeed, the family-resemblance approach does not seem very promising as a positive theory of art. For instance, Duchamp’s In Advance of a Broken Arm looks more like a standard shovel than any other artwork. A naive family resemblance approach might lead to the unfortunate conclusion that either this work is not art or that all shovels are (Carroll 1999, 223). This is probably of little importance to a true skeptic who doesn’t think the category of artworks will ever be definitely set. However, more moderate approaches have attempted to bring a stronger epistemic power to the family resemblance approach.

b. The Cluster Approach

Berys Gaut (2000) agrees with MacDonald and Weitz that any attempt to define art in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions is doomed to fail. Nevertheless, he defends an approach that can guide us to minimally understand the term “art,” capture borderline cases (cf. criterion [vii]), and establish fruitful theories with other human domains (cf. criterion [iii]). This is the cluster approach, which takes the form of a disjunction of relevant properties, none of which is necessary, but which are jointly sufficient. The idea is that, for something to qualify as an artwork, it must meet a certain number of these criteria, though none of them need to be met by all artworks. Gaut provides the following list:

(1) Possessing positive aesthetic properties … (2) being expressive of emotion … (3) being intellectually challenging … (4) being formally complex and coherent … (5) having a capacity to convey complex meanings; (6) exhibiting an individual point of view; (7) being an exercise of creative imagination (being original); (8) being an artifact or performance which is the product of a high degree of skill; (9) belonging to an established artistic form (music, painting, film, and so forth); (10) being the product of an intention to make an artwork (2000, 28).

For the most part, these criteria correspond to definitions proposed by other approaches. Roughly speaking, criteria (1) and (4) correspond to formalism, (2) and (6) to expressivism, (9) and (10) correspond to relationalism, and criteria (7) and (8) correspond to Kantian art theory—see Immanuel Kant: Aesthetics.

Gaut points out that the list can incorporate other elements in such a way as to modify the content but not the global form of the account. The approach is therefore good at incorporating new types of art—criterion [iii].

c. Limits of Skepticism

Skeptic approaches, and in particular the cluster approach, have been vigorously criticized. Note, however, that it has also inspired a non-skeptical approach called “disjunctive definitions” that is discussed in section 8.

A first and obvious objection against the cluster approach concerns the question of which criteria can be added to the list. For instance, why is the criterion “costs a lot” not on the list, while statistically, many artworks cost a lot? (Meskin 2007) More profoundly, the cluster approach has no resource to reject any irrelevant criteria—such as “has been made on a Tuesday” which can be true of some artworks. It would be absurd to elongate the disjunction infinitely with such criteria. Hence, without an element to connect the properties on the list, we run the risk of arbitrary clusters such as “flamp,” which stands for “either a flower or a lamp” (Beardsley 2004, 57). Intuitively, the term “art” is not as arbitrary as “flamp.”

Another question one may ask regarding the cluster theory is how many criteria an item must meet to be art. Some philosophical papers possess properties (3-6) and yet are not artworks (Adajian 2003). Presumably, some criteria are weighted more heavily than others, but this again leads to problems of arbitrariness (Fokt 2014).

Regarding skepticism more generally, Adajian (2003) points out that it has little resources for demonstrating that art has no essence. For instance, Dickie (1969) notices a problem with the most influential argument (by Weitz): it does not follow from the fact that all the sub-concepts of a category are open that the super-category is itself open. One can conceive of a closed super-category, such as “insect,” and sub-categories open to new, as of yet unknown, types of individuals—for example, a new species of dragonfly. Conversely, Wittgenstein may be right to argue that the super-category “game” is open, but this does not mean that sub-categories such as “football,” “role-playing game,” or “chess” are open. It seems, then, that there is no necessary symmetrical relation between open or closed sub-categories and open or closed super-categories.

4. Relational Definitions

Another reaction to classical definitions emerged in the second part of the 20th century. Contrary to skepticism, it did not give up on the attempt to spell out the necessary and sufficient conditions of art. Instead, it claimed that these conditions should not be found in the internal properties of artworks, but in the relational properties that hold between artworks and other entities, namely art institutions—for institutionalism—and art history—for historicism.

a. Institutionalism

Arthur Danto, in his seminal paper “The artworld” (1964), describes Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes as what inspired his institutionalist definition. These boxes, exhibited in an art gallery, are visually indistinguishable from the Brillo boxes found in supermarkets. But, crucially, the latter are not artworks. Danto concluded that the identity of an artwork depends not only on its internal properties, but also (and crucially) on relational properties such as the context of its creation, its place of exhibition, or the profession of its author. This led him to propose that artworks are constituted by being interpreted (see Irvin 2005 for a discussion). So, Warhol’s Brillo boxes are distinct from commonplace objects because they are interpreted in a specific way. It means that when Warhol made his Brillo boxes, he had an intention to inscribe the work in an artistic tradition or to depart from it, to comment on other artists, to mock them, and so on. Warhol’s interpretation of Brillo boxes is of a specific kind, it is related to the artworld—that is, related to a set of institutions and institutional players made up of art galleries, art critics, museum curators, collection managers, artists, conservatories, art schools, art historians, and so on.

According to Danto, a child dipping a tie in blue paint could not, on his own, make an artwork, even if he intended to make it prettier. Picasso, on the other hand, could dip the same tie in the same pot and turn it into an artwork. He would achieve this by virtue of his knowledge of the artworld, which he intends to summon through such a gesture. As the example of the child and the tie shows, Danto’s position implies that the creator of art possesses explicit knowledge of the artworld. Danto is thus led to deny that Paleolithic paintings, such as those in the Lascaux caves, can be art—a consequence he seems happy to accept (Danto 1964, 195). This result is highly counter-intuitive given that almost everyone intuitively attributes artistic status to these frescoes. What’s more, Danto excludes the vast majority of non-Western art and art brut. These problems are discussed in more detail below (4.a.ii).

George Dickie’s (1969) institutionalist definition aims to avoid Danto’s counterintuitive results. Dickie distinguishes three meanings of the term “art”: a primary (classificatory) meaning, a secondary (derivative) meaning, and an evaluative (prescriptive) meaning. For Dickie, throughout the history of art up to, roughly, Duchamp, the three meanings were intertwined. The primary meaning of art is what Dickie seeks to define, it reflects the sense of the term which would unify all artworks. The secondary meaning refers to objects that resemble paradigmatic work—for example, a seashell may be metaphorically qualified as an “artwork” given its remarkable proportions that are also used in many artworks. Finally, the third meaning corresponds to the evaluative use of the term art, as in “Your cake is a real work of art!”. Duchamp’s great innovation was to have succeeded in separating the primary from the secondary meaning, by creating works that in no way resembled paradigmatic works of the past (secondary meaning), but which nevertheless managed to be classified as artworks (primary meaning).

Indeed, Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel and Camille Claudel’s La petite châtelaine are not linked by a relationship of perceptual resemblance but are nevertheless linked by the fact that both sculptures have been recognized by the guarantors of the artworld as possessing certain qualities. It is this institutional recognition that would allow us to classify these two very different sculptures as artworks.

Dickie’s original definition of art is the following:

A work of art in the descriptive sense is (1) an artifact (2) upon which [a] some society or some sub-group of a society [b] has conferred [c] the status of candidate for appreciation (Dickie 1969, 254).

Condition (1) is simply the criterion that artworks are produced by people. It is in condition (2) that one finds Dickie’s most significant contribution to the debate. Let’s consider its various features: the society or sub-group to whom [a] refers should be understood as the relevant actors from the artworld (1969, 254). It may be a single person, such as the artist who created the artifact, but more commonly involves various actors such as gallerists, museum curators, critics, other artists, and so on. Condition [b] refers to the symbolic act of conferring a special status. Dickie compares it to the act of declaring someone as a candidate for alderman (idem, 255)—in a way reminiscent of Austin’s (1962) performative speech acts. This comparison illustrates that the symbolic act of conferring cannot be performed by just anyone in any context. They need to have a special role that allows them to act on behalf of the artworld.

To return to the above example from Danto, a child dipping a tie in paint doesn’t have the institutional status necessary to turn the artifact into an artwork. On the other hand, his father, a museum curator, could take hold of the tie and confer on it the status of art brut by exhibiting it. To perform this act successfully, the father must, according to Dickie, confer to it [c] the status of candidate for appreciation. This doesn’t mean that anyone needs to actually appreciate the tie, but only that, thanks to the status the curator has conferred it, people apprehend the tie in ways that they usually apprehend other artworks so as to find the experience worthy or valuable (Dickie 1969, 255). Of course, it seems circular to define an artwork using the notion of the artworld. Dickie readily admits this. Nevertheless, he argues that this circularity is not vicious, as it is sufficiently informative: we can qualify the artworld through a whole host of notions that do not directly summon up the notion of art itself. Dickie describes the artworld through, for instance, historical, organizational, sociological descriptions that make the notion more substantial than by describing it uninformatively in terms of the “people who make art art.”

It should also be noted that Dickie reformulated and then substantially modified his original definition in the face of various criticisms (see the section Further Reading below).

i. Advantages of Institutionalism

A definite advantage of institutionalist definitions is that their extension corresponds much better to the standard use of the term “art” than the classical definitions discussed above. Thus, since Dickie’s improvement over Danto’s initial idea, institutionalism fulfills criteria [i] to [vi], at least partially.

Indeed, it allows for the inclusion of [i] mediocre art, [ii] art produced by people who do not possess the concept “art,” and [iii] and avant-garde, future, or possible art—insofar as the status of artwork is attributed by the institutions of the artworld to these works. We’ll see that this last condition is open to criticism, but in any case, it allows institutionalism to explain without any problem why Duchamps’ readymades are artworks, which is not obvious from classical or skeptic theories. Art brut, cult objects (for example, prehistoric), video games, chimpanzee paintings, music created by AIs, non-existent or extraterrestrial types of objects, but also natural objects (for example, a banana) can become art as soon as these entities are adequately recognized by the artworld. In this way, arguments such as “It’s not art, my 5-year-old could do the same” that one sometimes hears about contemporary art lose all their weight.

Institutionalism also makes it possible to exclude [iv] purely natural objects, [v] what purports to be art but has completely failed, [vi] and non-artistic artifacts, including those with an aesthetic function—as long as the status of artwork has not been conferred on these objects by the relevant institutions. Again, this last condition is debatable, but it does help to explain why Aunt Jeanne’s beautiful Christmas tree or Jeremy’s selfie on the beach are not considered artworks.

ii. Limits of Institutionalism

Levinson (1979) and Monseré (2012) argue that primitive or non-Western arts, as well as art brut, are not made with an intention related to the artworld. But they do not need to wait for pundits—a fortiori from the Western artworld—to be appropriately qualified as art. Think for instance of Aloïse Corbaz’s work before Dubuffet or Breton exhibited her, or Judith Scott’s (see picture) before her recognition in the art brut world. Through their exhibitions of art brut and non-Western art, Dubuffet and Breton did not transform non-artistic objects into artworks, they rather helped to reveal works that were already art. Turning to another example: in the culture of the Pirahãs, a small, isolated group of hunter-gatherers living in the forests of Amazonia, there is no such thing as the artworld (Everett, 2008). Yet this group produces songs whose complexity, aesthetic interest, and expressiveness clearly make them, in the eyes of many, artworks. Similar remarks can be made about prehistoric works, such as those in the Chauvet cave.

Levinson (1979) and Monseré (2012) argue that primitive or non-Western arts, as well as art brut, are not made with an intention related to the artworld. But they do not need to wait for pundits—a fortiori from the Western artworld—to be appropriately qualified as art. Think for instance of Aloïse Corbaz’s work before Dubuffet or Breton exhibited her, or Judith Scott’s (see picture) before her recognition in the art brut world. Through their exhibitions of art brut and non-Western art, Dubuffet and Breton did not transform non-artistic objects into artworks, they rather helped to reveal works that were already art. Turning to another example: in the culture of the Pirahãs, a small, isolated group of hunter-gatherers living in the forests of Amazonia, there is no such thing as the artworld (Everett, 2008). Yet this group produces songs whose complexity, aesthetic interest, and expressiveness clearly make them, in the eyes of many, artworks. Similar remarks can be made about prehistoric works, such as those in the Chauvet cave.

What underlies counterexamples such as art brut, non-Western, or prehistoric art is that there seem to be reasons independent of institutionalization itself that justify artworld participants institutionalizing certain artifacts and not others. In line with this idea, Wollheim (1980, 157-166) proposed a major challenge for any institutional theory: either artworld participants have reasons for conferring the status of art or they do not. If they have reasons, then these are sufficient to determine whether an artifact is art. If they do not, then institutionalization is arbitrary, and there’s no reason to take artworld participants seriously. An institutional definition is therefore either redundant or arbitrary and untrustworthy.

To revisit a previous example, the museum curator must somehow convince his peers in the artworld that his son’s tie dipped in paint is a legitimate candidate for appreciation. For this, it seems intuitive that he must be able to invoke aesthetic, expressive, conceptual, or other reasons to justify his desire to exhibit this object. But if these reasons are valid, then the institutional theory is putting the cart before the horse: it’s not because the artifact is institutionalized that it is art, but because there are good reasons to institutionalize it (see also Zangwill’s Appendix on Dickie, 2007). Conversely, if there are no good reasons to institutionalize the artifact, then the father simply had a whim. If institutionalism still allows the father to confer the status of artwork, then institutionalization is arbitrary, and there is an impossibility of error on the part of participants in the artworld.

The objections discussed have been partially answered by more recent versions of institutionalism, see notably Abell (2011) and Fokt (2017).

b. Historicism

Starting in 1979, Jerrold Levinson sought to develop a definition of art that, while inspired by the institutionalist theses of Danto and Dickie, also avoided certain of their undesirable consequences. Levinson’s theory retains the intuition that art must be defined by relational properties of the works. However, instead of basing his definition on the artworld, Levinson emphasizes a work’s relationship to art history. Noël Carroll (1993) is another well-known advocate of historicism while theories put forward by Stecker (1997) and Davies (2015) also contain a historicist element and are discussed in section 8 below. Here, the focus is on Levinson’s account, which is the oldest, most elaborate, and most influential.

Levinson summarizes his position as follows:

[A]n artwork is a thing (item, object, entity) that has been seriously intended for regard-as-a-work-of-art, i.e., regard in any way preexisting artworks are or were correctly regarded (Levinson 1989, 21).

Before delving into the details, let’s consider an example. We have seen that the institutional definitions of Danto or Dickie struggled to account for art produced by someone from a culture that lacked our concept of art (4.a.ii). Levinson (1979, 238) discusses the case of an entirely isolated individual—imagine, for instance, Mowgli from The Jungle Book. Mowgli could create something beautiful, let’s say a colored stone sculpture, with the intention, among other things, of eliciting admiration from Bagheera. Although Mowgli does not possess the concept of art, and although his sculpture has not been instituted by any representative of the artworld, his artifact is related to past works through the type of intention deployed by Mowgli.

Indeed, one can highlight at least three types of resemblance between the intention with which Mowgli created his sculpture and that of past artists (1979, 235). Firstly, Mowgli wanted to endow his sculpture with formal aesthetic properties—symmetry, vibrant colors, skillful assembly… Secondly, he aimed to evoke a particular kind of experience in his spectators—aesthetic pleasure, admiration, interest… Thirdly, he intended his spectators to adopt a specific attitude towards his sculpture—contemplate it, closely examine its skillfully assembled form, recognize the success of the color palette.

To produce art, according to Levinson, Mowgli does not need to have in mind works from the past, but his production must have been created with these types of intention—as long as it is with these types of intention that the art of the past was created.

The resemblance between an artist’s intentions and those of past artists may seem to lead Levinson to a form of circularity, but that is not the case; it leads him instead to a successive referral of past intentions to past intentions that themselves refer to older ones until arriving, at the end of the chain, at the first art productions the world has known. For Levinson, one does not need to know precisely what these first arts are. What matters is that, at some point in the prehistory of art, there are objects that can easily be called art—like the Chauvet caves (see picture) or the Venus of Willendorf.

This way of defining art can be compared to how biologists typically classify the living world. A biological genus is defined through its common origins, even though individuals of different species may have evolved divergently. The first arts are comparable to the common ancestors of species in the same genus. To know what this common ancestor looked like, one must trace the genetic lineages. But there is no need to know exactly what these ancestors looked like to know that the species belong to the same genus.

Notice that Carroll (1993) proposes a historicist definition of art that does not require an intentional connection like Levinson’s. For Carroll, there is no need for artists to have intentions comparable to those of previous artists; instead, their works must allow a connection to the past history that forms a coherent narrative. If an object can be given an intelligible place in the development of existing artistic practices, then it can also be considered art.

i. Advantages of Historicism

The first advantage of historicism over the theories reviewed so far is to explain the diversification of ways of making and appreciating art. From classical painting to horror movies, from ballet to readymades, the property of being considered-as-art gradually complexifies. Thus, the apparent impression of disparity or lack of unity in what is called “art” is attenuated. A whale, a bat, and a horse strike us as being very different, yet their common ancestor can be traced, explaining their common classification as mammals. It would be the same for a video game, a cathedral, and a performance by Joseph Beuys: although quite different, their common origin can be traced, thus explaining what binds them together. And their historical connection would be the only essential element shared by all these artworks.

Historicism also enjoys several advantages over institutionalism while being able to account for cases that institutionalism deals with successfully. The first advantage is that it sidesteps the issue concerning works not recognized by the artworld (criterion [ii]). A second advantage over institutionalism is what one may call “the primacy of artists over the public.” Danto’s or Dickie’s institutionalism implies that someone belonging to the artworld simply cannot be mistaken in their judgment that something is art. This is not the case with Levinson’s theory. Thus, an art historian who comes across an Inuit toy that was not created with artistic intentions and still catalogs it in a book as an “Inuit artwork” would be mistaken about the status of this artifact, even if, from their perspective, there are good reasons to classify it as such: according to Levinson, if this toy was not created with the right intentions, then it cannot become art just because an archaeologist or curator considers it as such (cf. Levinson’s discussion of ritual objects 1979, 237). By the same token, historicism has no problem explaining how an artifact can be an artwork before being recognized by institutions, for example, the early works of Aloïse Corbaz and Judith Scott. Before being institutionalized by art brut curators, these artists nonetheless created artifacts with the intention that they were regarded-as-works-of-art.

For other advantages of historicism, see the references in the section Further Reading below.

ii. Limits of Historicism

The first difficulty of historicism concerns the first arts. It can be introduced through the age-old problem of Euthyphro, in which Socrates shows Euthyphro that he is unable to say whether a person is pious because loved by the gods or loved by the gods because pious. Here, the question would be: Is something considered art because it fits into the history of art, or does something fit into the history of art because it is art? (Davies 1997)

Outside of first arts, Levinson’s answer is clear: something is considered art when it fits into the history of art through the intention-based relation described above. However, this answer is not possible for first arts because, by definition, they have no artistic predecessors. In his initial definition, Levinson simply stipulates that first arts are arts (Levinson 1979, 249). Consequently, he is forced to admit that first arts are art not because they fit into the history of art; hence the problem of Euthyphro.

Gregory Currie (1993) highlights a similar problem through the following thought experiment: imagine that there is a discovery on Mars of a civilization older than any that has ever existed on Earth. Long before the first arts appeared on our planet, Martians were creating objects that we would unquestionably call “art.” The reason for labeling these objects as “art” does not seem tied to the contingent history of human art but rather to ahistorical aspects.

A last problematic case that can be raised in connection with the criterion [vii] concerns the intentions governing activities seemingly more mundane than art. In particular, a five-year-old child drawing a picture to hang on the fridge has a similar intention to that of a painter who wants to present their work—the five-year-old wants to evoke admiration, create an object that is as beautiful as possible, and so on. Examples can be multiplied easily. Think of the careful preparation of a Christmas tree, the elegant furnishing of a living room, a spicy diary, or vacation photos on Instagram (see Carroll 1999, 247). In all these cases, the intentions clearly resemble those of paradigmatic works of the past but we don’t want to label all of them as artworks.

Levinson replied to some of these objections, but this goes beyond the scope of this article (see the section Further Reading below).

5. Feminist Aesthetics, Black Aesthetics, and Anti-Discriminatory Approaches

In addition to the skeptical approaches discussed in section 3, important criticisms against the project of defining art have been raised within feminist aesthetics, Black aesthetics, and anti-discriminatory approaches to art. In contrast with skepticism, these critiques constitute a constructive challenge for a definition of art—and especially for relational views (see section 4)—rather than an anti-essentialist position.

Two kinds of criticisms are distinguished: (a) those made by artists and (b) those made by philosophers and theorists of art. Art practiced by women, Black people, queer artists, or other groups underrepresented in the history of (Western) art can challenge traditional approaches to art notably by highlighting how the works and perspectives from members of these groups have been unfairly marginalized, ignored, discarded, or stripped of credibility and value. In parallel, one can find critiques from philosophers whose approach is guided by their sensitivity to discrimination, which leads them to detect problematic issues in the necessary and sufficient conditions of existing art definitions.

a. The Art as Critique

Let’s start by stating something quite obvious: not all art produced by a person who suffers from discrimination constitutes a critique of this discrimination. Similarly, not all feminist or anti-racist criticisms go in the same direction. For instance, Judy Chicago’s work The Dinner Party—a 1979 installation where plates shaped like vaginas and bearing the names of important women figures are arranged on a triangular table (see picture)—has been praised as a seminal feminist artwork but has also been criticized as naively essentialist (Freeland 2002, Chap. 5). It is thus difficult to make general statements that apply to all the relevant artworks.

That being said, much feminist art, which gained prominence during the 20th century and especially its second half, bears a certain continuity with Dadaism and conceptual art (Korsmeyer and Brand Weiser 2021). Works created by feminist artists have often radically challenged the most traditional conceptions of art (see section 2.a.)—think, for instance, of the protest art of the Guerrilla Girls or Marina Abramović’s performances.

Non-Western art and art made by marginalized communities, such as artworks by women, have also often been excluded or not considered central to the project of defining art. For this reason, some of these works can unsettle and destabilize the traditional Western conceptions of art discussed above. For instance, many cultures in Africa do not make a rigid distinction between the interpretation and creation of art, everyday practices of crafting, and “contemplation” of beauty (see Taylor 2016, 24). As Taylor notes, these diverse practices can serve as points of comparison with classical Western art for those who seek to elaborate a more general theory of art and so to respect the criteria [ii] and [iii].

It is noteworthy that philosophers have not always had this inclusive attitude towards art produced by marginalized artists. Batteaux’s or later Hegel’s notion of “fine art” (see section 2.a.ii) leads to the neglect of any type of art that does not fit into the “noble” categories of painting, sculpture, architecture, music, poetry, dance, or theater. These categories exclude art practices that have been associated with women or non-Western cultures, relegating these practices to a lesser status, such as craft. Think, for instance, about Otomi embroidery—a Mesoamerican art form—or about quilts, which have traditionally been made by women. These textile creations are not among the fine art categories. It was only in the latter part of the 20th century that some quilts started to be recognized as artworks, exhibited in art galleries and museums, thanks notably to the work of feminist artists such as Radka Donnell, who have used quilts as a means to subvert traditional, male-dominated perspectives on art. Donnell even considered quilts as a liberation issue for women (for example, Donnell 1990).

The emergence of expressivism and formalism, which also challenged the fine art categories, has perhaps helped philosophers and art theorists to adopt a more universalist and hence more inclusive approach to the diversity of the arts (Korsmeyer 2004, 111). Unfortunately, it is unclear whether this helped women and discriminated minorities to be recognized as artists since the art forms favored by formalism or expressivism have remained male- and white-dominated (see Freeland 2002, Chap.5 and Korsmeyer and Brand Weiser 2021, Sect. 4 for a discussion).

b. Philosophical Critiques

Korsmeyer and Brand Weisser (2021), two important feminist aestheticians, state that “There is no particular feminist ‘definition’ of art, but there are many uses to which feminists and postfeminists turn their creative efforts.” Similar remarks have been made for Black aesthetics (Taylor 2016, 23). As far as definitions of art are concerned, much effort in these traditions has concentrated on pointing to biases from prevalent proposals. A point of emphasis has been in explaining structures of power reflected in the concept of art, often from a Marxist perspective (Korsmeyer 2004, 109). Some philosophers working on minority viewpoints see typical attempts to provide necessary and sufficient conditions for art with suspicion and as being systematically guilty of biases regarding gender, race, or class (Brand Weiser 2000, 182).

A striking example of such criticisms is the work of Peg Brand Weiser (for example, 2000). In addition to pointing to the excluding nature of the fine art categories that were stressed above (section 5.a.), she highlights important objections to the relational definitions (section 4). Concerning institutionalism (section 4.a.), a way to reconstruct Brand Weiser’s argument is the following. According to this theory, institutional authorities have the power to make art. However, these authorities historically are (and still mostly are) white men who have acquired their institutional power by virtue of their male and white privilege (among other factors) and whose perspective on what should count as art is biased. Thus, the institutional definition is flawed because it inherits the biases of the authorities that decide what is art.

Note that this criticism holds even if institutions change and gradually become less patriarchal. According to institutionalism, indeed, quilts weren’t art until the 1970s—when art authorities started giving institutional accolades to this practice. However, it seems that some quilts always have been art, only of a neglected kind (cf. the counterexample of art brut in section 4.a.ii).

Brand Weiser also criticizes historicism and in particular Carroll’s version (see section 4.b.). What is art, according to this definition, depends on what has been considered to be well-established art practices in the past. However, since these practices have long been exclusive of arts practiced by marginalized and underrepresented groups, this makes the historicist definition decidedly suspect. Like the institutionalism of Danto or Dickie, this definition is flawed because it inherits historically prevalent biases.

In addition to these criticisms, Brand Weiser has also made positive proposals for a non-biased definition. She offers six recommendations that a definition of art should adopt; they can be summarized with these three points: (1) we must recognize that past art and aesthetic theories have been dominated by people with a particular taste and agenda that may suffer racist and sexist biases, (2) the definition of fine arts is flawed, (3) “gender and race are essential components of the context in which an artwork is created and thus cannot be excluded from consideration in procedural […] definitions of “art”” (Brand Weiser 2000, 194).

There are potential limitations to Brand Weiser’s critique. First, concerning institutionalism, while her criticisms apply to Danto and Dickie’s versions, it should be noted that more recent versions may be able to avoid them. For instance, Abel (2011) and Fokt (2017) propose characterizations of art institutions that can exist independently of the Western art world and its white-dominated authorities (see section 4.a.ii).

Concerning historicism, while Brand Weiser’s criticisms may apply to Carroll’s version, it is less evident that it applies to Levinson’s. This is because, according to the latter, new artworks must be connected to artworks from the past through the intentions of artists. Thus, for Levinson, what makes something an artwork today is not the art practices, art genres, art institutions, famous artworks, or even written art histories. These may well be biased while the relevant artistic intentions are not so biased. Think again about our Mowgli example (section 4.b.): his colored rock sculpture is art because his intention in creating it connected to past artistic intentions—let’s say intentions to overtly endow the sculpture with formal aesthetic properties. Arguably, these kinds of intentions need not be polluted with racism or sexism. If they are not, then Levinson’s historicism can avoid Brand Weiser’s criticism.

Regarding Brand Weiser’s positive suggestions, while (1) and (2) are important historical lessons that philosophers such as Dutton (2006), Abel (2011), Davies (2015), Fokt (2017), and Lopes (2018) have taken into account, (3) may seem too strong. Gender, social class, and sexual orientation are important sociological contextual factors, but one should resist importing them into (any) definition of art to avoid an infinite iteration of the import of contextual factors to which one would be led by parity of reasoning. For instance, Michael Baxandall (1985) shows that the intention to create, say, the Eiffel Tower could have emerged only thanks to a dozen contextual conditions such as the frequentations of the artist, views on aesthetics popular at the time, the trend for positivism regarding science, the state of technological advances, and Gustave Eiffel interests for the technic of puddling. These too are essential components of the context in which this artwork has been created (to use Brand Weiser’s formulation), but it doesn’t seem that all such variables, and more, should be included in a definition of art, however important they are to understand the relevant artworks.

It bears repeating that feminist and anti-racist approaches do not have an essential and particular definition of art. Nevertheless, their positive proposals show that such approaches can lead to new definitions of art, definitions that would pay particular attention to avoiding the negative biases and prejudicial attitudes towards minorities and marginalized groups, attitudes that have all-too-often polluted the (Western) history of art.

6. Functionalist Definitions

A lesson that may be drawn from the discussion of relational approaches is that it is difficult to define art without reference to the non-relational or internal properties of artifacts if one wants to avoid arbitrary definitions. The family of functionalist theories resurrects the idea shared by classical definitions that if x is art, it is in virtue of a non-relational property of x. Here, what x must possess is an aesthetic function.

a. Neo-Formalist Functionalism

A significant portion of functionalist approaches resembles and is inspired by classical formalism (see section 2.c.) since its main proponents acknowledge a close connection between the aesthetic function of artworks and formal aesthetic properties directly accessible by the senses. This sub-family, however, distinguishes itself from classical formalism since it is the aesthetic function in an artifact that makes it an artwork rather than the mere presence of aesthetic properties. Let’s call this sub-family neo-formalist functionalism (or just neo-formalism).

Monroe Beardsley (1961) and more recently Nick Zangwill are the major representatives of this line of thought. Zangwill is skeptical of attempts to include the most extreme cases of contemporary art in a definition of art (2007, 33). Instead, he focuses on the pleasure most of us experience in engaging in more traditional artistic activities and on the metaphysics of formal aesthetic properties.

Formal aesthetic properties supervene on properties that can be perceived through our five senses. For instance, the elegance of a statue supervenes in its curves—that is, there can be no difference in the elegance of the statue without a difference in its curves (see Supervenience and Determination). The elegance of a statue is a formal aesthetic property since its curves are non-aesthetic properties we can perceive through our eyes or hands. This metaphysical position leads Zangwill to believe that what fascinates us primarily when we create or contemplate an artwork are formal aesthetic properties: what strikes us when we listen to music is primarily the balance between instruments, and this balance supervenes on the sound properties of the instruments and tempo; what pleases us when we post a photo on Instagram is finding the appropriate filter to make our image enchanting. By choosing a filter, we do nothing more than decide to endow our photo with formal aesthetic properties based on non-aesthetic properties that can be perceived.

Zangwill’s neo-formalist definition reflects this idea: x is an artwork if and only if (a) x is an artifact endowed with aesthetic properties supervening on non-aesthetic properties, (b) the designer of x had the insight to provide x with aesthetic properties via non-aesthetic properties, and (c) this initial intention has been minimally successful (Zangwill 1995, 307).

Criterion (a) reflects Zangwill’s metaphysical position; (b) reflects the functionalist nature of this approach: to have an aesthetic function, something needs to have been conceived to possess aesthetic properties—which excludes natural objects (see criterion [iv]). Of course, the aesthetic function thus endowed is not necessarily the only one that artworks possess; religious artifacts can have both an aesthetic and a sacred function. More importantly, just like Kant, Zangwill argues that art cannot be created simply by applying aesthetic rules; one must have insight, a moment of “aesthetic understanding” (Zangwill 2007, 44), about how aesthetic properties will be instantiated by non-aesthetic properties. Finally, (c) ensures that an artist’s intention must be minimally successful. There can be dysfunctional artworks, but not so dysfunctional that they fail to have any aesthetic properties at all—this respects the criterion [v] to exclude what purports to be art but has failed completely.

As a “moderate” neo-formalist (as he calls himself), Zangwill does not deny that properties broader than formal aesthetic properties can make an artwork overall interesting—this is the case for relational properties such as originality, for example (2000, 490). However, genuine artworks (and, in fact, most artworks) must possess formal aesthetic functions.

This neo-formalist idea, though moderate, excludes conceptual artworks, since they have no formal aesthetic properties. If we consider Duchamp’s Fountain, we see only an ordinary urinal devoid of relevant formal aesthetic properties—in fact, we would not understand Duchamp’s attempt if we interpreted it as a work aiming to display the elegance of a urinal’s curves (Binkley 1977). But remember that this would be the point of neo-formalism because it reacts to institutionalism. To be more specific, Zangwill considers that these works indirectly involve aesthetic functions since they refer to, or are inspired by, traditional works of art, which are, in turn, endowed with aesthetic functions. Provocatively, Zangwill labels these cases as “second-order” and even “parasite” types of artworks (2002, 113). In doing so, Zangwill accounts for the primacy of formal aesthetic properties in defining art, while at the same time accounting for contemporary art.

i. Advantages of Neo-Formalist Functionalism

The main advantage of neo-formalism regards its efficiency in capturing an important aspect of our daily engagement with artworks: they are “evaluative artifacts” (Zangwill 2007, 28) in the sense that, from Minoan frescos to Taeuber-Arp’s non-representational paintings, these artifacts have been positively evaluated based on the formal beauty intended by their creator. Interestingly, as Korsmeyer (2004, 111) points out, formalism (and its heir) paves the way for appreciation of work created by non-Western cultures—just as we can appreciate beautiful creations of the past.

By contrast, art theorists and philosophers still have a hard time explaining to the person on the street why the most radical cases of conceptual works, such as Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan (a banana stuck on a wall by duct tape), should be considered art. It seems that “non-aesthetic” works—works that do not aim at instantiating aesthetic properties, such as hyper-realistic sculptures or conceptual art—are indeed not considered as paradigmatic examples of artworks by laypeople. Zangwill’s ambition, in opposition to institutionalism, consists precisely in focusing on paradigmatic cases (for example, The Fall of Icarus by Bruegel the Older, see picture)  and avoiding a definition of art based on exceptions. In the same vein, Roger Pouivet (2007, 29) adds that practicing a “theory for exception” as institutionalism does is even harmful. The risk would be to provide a definition that would be a purely scholastic exercise but would no longer be related to what is the main interest of art.

and avoiding a definition of art based on exceptions. In the same vein, Roger Pouivet (2007, 29) adds that practicing a “theory for exception” as institutionalism does is even harmful. The risk would be to provide a definition that would be a purely scholastic exercise but would no longer be related to what is the main interest of art.

Another advantage of neo-formalism is that the definition of art clearly aligns with its ontology within this theory. Zangwill’s definition is indeed based on an ontological analysis of artifacts and formal aesthetic properties. By contrast, the ontology underlying institutionalism is much less clear (Irvin and Dodd 2017).

ii. Limits of Neo-Formalist Functionalism

Limitations to the neo-formalist approach are numerous, given that its very ambition is not to capture all so-called “exceptions” of contemporary art. On paper, neo-formalism meets criterion [iii]: a new type of art can emerge as long as the artworks constituting it possess an aesthetic function. However, its rejection of many contemporary artworks is at odds with the ambition to offer a definition of art across the board. In such a case, it is good to apply the principle of reflective equilibrium, which attempts to determine a balance between the coherence of the theory and its ability to capture our intuitions.

A first notable worry concerns whether “non-aesthetic” works are considered as genuine artworks by Zangwill or as artworks “in name only.” According to his own definition, Fountain is not a genuine artwork, but Zangwill wants to account for it anyway. The status of “second-order” or “parasite” art should thus be clarified.

Another worry concerns artworks such as Tracey Emin’s My Bed – an unkempt bed littered with debris—or, to a lesser extent, Francis Bacon’s tortured works. Contrary to counterexamples such as conceptual arts, these cases were realized with an aesthetic insight, the one of providing them with negative formal aesthetic properties. Since neo-formalism focuses on positive aesthetic formal properties, it says almost nothing about these negative cases—see, by contrast, expressivism section 2.b. These cases are nevertheless quite complex since an artwork can possess an overall (or organic) positive value by possessing intended negative proper parts (Ingarden 1963, Osborne 1952). If one wishes to conserve the idea that art involves the insight to endow artifacts with positive aesthetic properties (which leads to positive appreciation), one must significantly complexify the neo-formalist approach. Indeed, the insight should focus on two layers of aesthetic properties–those concerning the aesthetic properties of the proper parts and those concerning the aesthetic property of the whole.

A broader objection challenges Zangwill’s metaphysical claim that formal aesthetic properties supervene on properties perceived by the five senses. Indeed, many internal aesthetic properties of literary works are central to this art form but are not directly accessible through the senses. Think for instance of the dramatic beauty of tragedy, the elegance with which a character’s psychology is depicted, or the exquisite comic of a remark in a dialogue. If this is true, this is a major objection to most metaphysical approaches to formal aesthetic properties via perceptual properties (Binkley 1977; Shelley 2003). Since a novel cannot be conceived with the intention that it possesses formal aesthetic properties supervening on perceptual properties, a novel cannot be art. Zangwill swallows this bitter pill: by extending “art” to objects that do not possess formal properties, we would commit the same mistake as naming “jade” both jadeite and nephrite (Zangwill 2002). Literature would be taken for art due to metaphorical resemblances with formal aesthetic artifacts. It is not a matter of rejecting the value of literature; it is simply denying that it has formal aesthetic properties, therefore being genuine art.

This response is highly problematic. Firstly, while it is true that narrative properties do not supervene on perceptual properties, we nevertheless enjoy them in the same way as we enjoy formal properties, namely through our sensibility (emotions, feelings, impressions…). Moreover, we attribute evaluative properties supervening on the internal properties of literary works with the same predicates used for formal properties: we speak of elegant narration, stunning style, the compelling rhythm of the plot, the sketchy psychology of a character… Why should these narrative properties be only metaphorically aesthetic since they share these two relevant features with formal aesthetic properties (Goffin 2018)? In a nutshell, narrative properties cannot be excluded from the domain of aesthetic properties just because it could consist of an exception in our ontological system—this is the “No true Scotsman” fallacy (but see Zangwill 2002, 116).

Finally, Zangwill’s definition is both too narrow and too broad. It is too narrow since it excludes literature from art although works such as Jane Eyre, The Book of Sand, or the Iliad seem to be paradigmatic examples of artworks. It is too broad since it includes any artifact created for aesthetic purposes from an insight—such as floral arrangements or even (some) cake decorations (Zangwill 1995). Such cases risk fatal consequences if we want to preserve criterion [vi] and exclude non-artistic artifacts (including those with an aesthetic function).

Patrick Grafton-Cardwell (2021) and, to a certain extent, Marcia Eaton (2000) suggest a definition of art able to keep the spirit of functionalism while bypassing the too-broad objection. They argue that the function of artworks consists in aesthetically engaging—that is, to direct our attention to aesthetic properties.

Cake decorations may indeed be designed with the insight to endow them with aesthetic properties, but not with the intention of making us contemplate or reflect on the aesthetic properties of these cakes. One can even argue, with Eaton, that in our culture, cake decorations do not deserve the relevant aesthetic attention—while letting the door open for another culture that would consider cake decoration as deserving it.

While the aesthetic engagement approach sidesteps a major objection of neo-formalist functionalism, it provides no resource (except our intuitions) to distinguish aesthetic engagement from other types of engagement—for example, epistemic engagement toward a philosophical question. It thus seems too uninformative and vague to have sufficient predictive power—cf. criterion [iii]. That being said, Eaton argues that aesthetic engagement concerns attention toward the internal features of an object that can produce delight. This is, however, still too vague (see Fudge 2003).

7. Determinable-Determinate Definitions

Up to this point, this article has given a general definition of art. To then define individual arts (for example, paintings), one would have to add further conditions to the general definition. One may consider this as a genus-species view of art: the super-category has a positive definition, involving necessary and sufficient conditions, that is independent of the sub-categories. In biology, the class of mammals is defined by attributes such as being vertebrate, having warm blood, nursing their young with maternal milk, and so on. The different species belonging to this class (bats, whales, ponies, humans…) share these properties and distinguish themselves by species-specific properties. In aesthetics, art would be a super-category that contains a set of sub-categories such as literature, music, sculpture… This idea is precisely what is attacked by skeptics.