Propositional Logic

Propositional logic, also known as sentential logic and statement logic, is the branch of logic that studies ways of joining and/or modifying entire propositions, statements or sentences to form more complicated propositions, statements or sentences, as well as the logical relationships and properties that are derived from these methods of combining or altering statements. In propositional logic, the simplest statements are considered as indivisible units, and hence, propositional logic does not study those logical properties and relations that depend upon parts of statements that are not themselves statements on their own, such as the subject and predicate of a statement. The most thoroughly researched branch of propositional logic is classical truth-functional propositional logic, which studies logical operators and connectives that are used to produce complex statements whose truth-value depends entirely on the truth-values of the simpler statements making them up, and in which it is assumed that every statement is either true or false and not both. However, there are other forms of propositional logic in which other truth-values are considered, or in which there is consideration of connectives that are used to produce statements whose truth-values depend not simply on the truth-values of the parts, but additional things such as their necessity, possibility or relatedness to one another.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- History

- The Language of Propositional Logic

- Syntax and Formation Rules of PL

- Truth Functions and Truth Tables

- Definability of the Operators and the Languages PL’ and PL”

- Tautologies, Logical Equivalence and Validity

- Deduction: Rules of Inference and Replacement

- Natural Deduction

- Rules of Inference

- Rules of Replacement

- Direct Deductions

- Conditional and Indirect Proofs

- Axiomatic Systems and the Propositional Calculus

- Meta-Theoretic Results for the Propositional Calculus

- Other Forms of Propositional Logic

- References and Further Reading

1. Introduction

A statement can be defined as a declarative sentence, or part of a sentence, that is capable of having a truth-value, such as being true or false. So, for example, the following are statements:

- George W. Bush is the 43rd President of the United States.

- Paris is the capital of France.

- Everyone born on Monday has purple hair.

Sometimes, a statement can contain one or more other statements as parts. Consider for example, the following statement:

- Either Ganymede is a moon of Jupiter or Ganymede is a moon of Saturn.

While the above compound sentence is itself a statement, because it is true, the two parts, “Ganymede is a moon of Jupiter” and “Ganymede is a moon of Saturn”, are themselves statements, because the first is true and the second is false.

The term proposition is sometimes used synonymously with statement. However, it is sometimes used to name something abstract that two different statements with the same meaning are both said to “express”. In this usage, the English sentence, “It is raining”, and the French sentence “Il pleut”, would be considered to express the same proposition; similarly, the two English sentences, “Callisto orbits Jupiter” and “Jupiter is orbited by Callisto” would also be considered to express the same proposition. However, the nature or existence of propositions as abstract meanings is still a matter of philosophical controversy, and for the purposes of this article, the phrases “statement” and “proposition” are used interchangeably.

Propositional logic, also known as sentential logic, is that branch of logic that studies ways of combining or altering statements or propositions to form more complicated statements or propositions. Joining two simpler propositions with the word “and” is one common way of combining statements. When two statements are joined together with “and”, the complex statement formed by them is true if and only if both the component statements are true. Because of this, an argument of the following form is logically valid:

Paris is the capital of France and Paris has a population of over two million.

Therefore, Paris has a population of over two million.

Propositional logic largely involves studying logical connectives such as the words “and” and “or” and the rules determining the truth-values of the propositions they are used to join, as well as what these rules mean for the validity of arguments, and such logical relationships between statements as being consistent or inconsistent with one another, as well as logical properties of propositions, such as being tautologically true, being contingent, and being self-contradictory. (These notions are defined below.)

Propositional logic also studies way of modifying statements, such as the addition of the word “not” that is used to change an affirmative statement into a negative statement. Here, the fundamental logical principle involved is that if a given affirmative statement is true, the negation of that statement is false, and if a given affirmative statement is false, the negation of that statement is true.

What is distinctive about propositional logic as opposed to other (typically more complicated) branches of logic is that propositional logic does not deal with logical relationships and properties that involve the parts of a statement smaller than the simple statements making it up. Therefore, propositional logic does not study those logical characteristics of the propositions below in virtue of which they constitute a valid argument:

- George W. Bush is a president of the United States.

- George W. Bush is a son of a president of the United States.

- Therefore, there is someone who is both a president of the United States and a son of a president of the United States.

The recognition that the above argument is valid requires one to recognize that the subject in the first premise is the same as the subject in the second premise. However, in propositional logic, simple statements are considered as indivisible wholes, and those logical relationships and properties that involve parts of statements such as their subjects and predicates are not taken into consideration.

Propositional logic can be thought of as primarily the study of logical operators. A logical operator is any word or phrase used either to modify one statement to make a different statement, or join multiple statements together to form a more complicated statement. In English, words such as “and”, “or”, “not”, “if … then…”, “because”, and “necessarily”, are all operators.

A logical operator is said to be truth-functional if the truth-values (the truth or falsity, etc.) of the statements it is used to construct always depend entirely on the truth or falsity of the statements from which they are constructed. The English words “and”, “or” and “not” are (at least arguably) truth-functional, because a compound statement joined together with the word “and” is true if both the statements so joined are true, and false if either or both are false, a compound statement joined together with the word “or” is true if at least one of the joined statements is true, and false if both joined statements are false, and the negation of a statement is true if and only if the statement negated is false.

Some logical operators are not truth-functional. One example of an operator in English that is not truth-functional is the word “necessarily”. Whether a statement formed using this operator is true or false does not depend entirely on the truth or falsity of the statement to which the operator is applied. For example, both of the following statements are true:

- 2 + 2 = 4.

- Someone is reading an article in a philosophy encyclopedia.

However, let us now consider the corresponding statements modified with the operator “necessarily”:

- Necessarily, 2 + 2 = 4.

- Necessarily, someone is reading an article in a philosophy encyclopedia.

Here, the first example is true but the second example is false. Hence, the truth or falsity of a statement using the operator “necessarily” does not depend entirely on the truth or falsity of the statement modified.

Truth-functional propositional logic is that branch of propositional logic that limits itself to the study of truth-functional operators. Classical (or “bivalent”) truth-functional propositional logic is that branch of truth-functional propositional logic that assumes that there are are only two possible truth-values a statement (whether simple or complex) can have: (1) truth, and (2) falsity, and that every statement is either true or false but not both.

Classical truth-functional propositional logic is by far the most widely studied branch of propositional logic, and for this reason, most of the remainder of this article focuses exclusively on this area of logic. In addition to classical truth-functional propositional logic, there are other branches of propositional logic that study logical operators, such as “necessarily”, that are not truth-functional. There are also “non-classical” propositional logics in which such possibilities as (i) a proposition’s having a truth-value other than truth or falsity, (ii) a proposition’s having an indeterminate truth-value or lacking a truth-value altogether, and sometimes even (iii) a proposition’s being both true and false, are considered. (For more information on these alternative forms of propositional logic, consult Section VIII below.)

2. History

The serious study of logic as an independent discipline began with the work of Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Generally, however, Aristotle’s sophisticated writings on logic dealt with the logic of categories and quantifiers such as “all”, and “some”, which are not treated in propositional logic. However, in his metaphysical writings, Aristotle espoused two principles of great importance in propositional logic, which have since come to be called the Law of Excluded Middle and the Law of Contradiction. Interpreted in propositional logic, the first is the principle that every statement is either true or false, the second is the principle that no statement is both true and false. These are, of course, cornerstones of classical propositional logic. There is some evidence that Aristotle, or at least his successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus (d. 287 BCE), did recognize a need for the development of a doctrine of “complex” or “hypothetical” propositions, that is, those involving conjunctions (statements joined by “and”), disjunctions (statements joined by “or”) and conditionals (statements joined by “if… then…”), but their investigations into this branch of logic seem to have been very minor.

More serious attempts to study statement operators such as “and”, “or” and “if… then…” were conducted by the Stoic philosophers in the late 3rd century BCE. Since most of their original works—if indeed, these writings were even produced—are lost, we cannot make many definite claims about exactly who first made investigations into what areas of propositional logic, but we do know from the writings of Sextus Empiricus that Diodorus Cronus and his pupil Philo had engaged in a protracted debate about whether the truth of a conditional statement depends entirely on it not being the case that its antecedent (if-clause) is true while its consequent (then-clause) is false, or whether it requires some sort of stronger connection between the antecedent and consequent—a debate that continues to have relevance for modern discussion of conditionals. The Stoic philosopher Chrysippus (roughly 280-205 BCE) perhaps did the most in advancing Stoic propositional logic, by marking out a number of different ways of forming complex premises for arguments, and for each, listing valid inference schemata. Chrysippus suggested that the following inference schemata are to be considered the most basic:

- If the first, then the second; but the first; therefore the second.

- If the first, then the second; but not the second; therefore, not the first.

- Not both the first and the second; but the first; therefore, not the second.

- Either the first or the second [and not both]; but the first; therefore, not the second.

- Either the first or the second; but not the second; therefore the first.

Inference rules such as the above correspond very closely to the basic principles in a contemporary system of natural deduction for propositional logic. For example, the first two rules correspond to the rules of modus ponens and modus tollens, respectively. These basic inference schemata were expanded upon by less basic inference schemata by Chrysippus himself and other Stoics, and are preserved in the work of Diogenes Laertius, Sextus Empiricus and later, in the work of Cicero.

Advances on the work of the Stoics were undertaken in small steps in the centuries that followed. This work was done by, for example, the second century logician Galen (roughly 129-210 CE), the sixth century philosopher Boethius (roughly 480-525 CE) and later by medieval thinkers such as Peter Abelard (1079-1142) and William of Ockham (1288-1347), and others. Much of their work involved producing better formalizations of the principles of Aristotle or Chrysippus, introducing improved terminology and furthering the discussion of the relationships between operators. Abelard, for example, seems to have been the first to clearly differentiate exclusive disjunction from inclusive disjunction (discussed below), and to suggest that inclusive disjunction is the more important notion for the development of a relatively simple logic of disjunctions.

The next major step forward in the development of propositional logic came only much later with the advent of symbolic logic in the work of logicians such as Augustus DeMorgan (1806-1871) and, especially, George Boole (1815-1864) in the mid-19th century. Boole was primarily interested in developing a mathematical-style “algebra” to replace Aristotelian syllogistic logic, primarily by employing the numeral “1” for the universal class, the numeral “0” for the empty class, the multiplication notation “xy” for the intersection of classes x and y, the addition notation “x + y” for the union of classes x and y, etc., so that statements of syllogistic logic could be treated in quasi-mathematical fashion as equations; for example, “No x is y” could be written as “xy = 0”. However, Boole noticed that if an equation such as “x = 1” is read as “x is true”, and “x = 0” is read as “x is false”, the rules given for his logic of classes can be transformed into a logic for propositions, with “x + y = 1” reinterpreted as saying that either x or y is true, and “xy = 1” reinterpreted as meaning that x and y are both true. Boole’s work sparked rapid interest in logic among mathematicians. Later, “Boolean algebras” were used to form the basis of the truth-functional propositional logics utilized in computer design and programming.

In the late 19th century, Gottlob Frege (1848-1925) presented logic as a branch of systematic inquiry more fundamental than mathematics or algebra, and presented the first modern axiomatic calculus for logic in his 1879 work Begriffsschrift. While it covered more than propositional logic, from Frege’s axiomatization it is possible to distill the first complete axiomatization of classical truth-functional propositional logic. Frege was also the first to systematically argue that all truth-functional connectives could be defined in terms of negation and the material conditional.

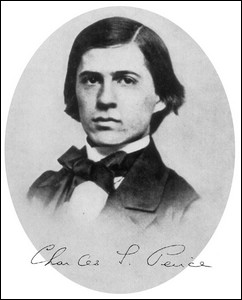

In the early 20th century, Bertrand Russell gave a different complete axiomatization of propositional logic, considered on its own, in his 1906 paper “The Theory of Implication”, and later, along with A. N. Whitehead, produced another axiomatization using disjunction and negation as primitives in the 1910 work Principia Mathematica. Proof of the possibility of defining all truth functional operators in virtue of a single binary operator was first published by American logician H. M. Sheffer in 1913, though American logician C. S. Peirce (1839-1914) seems to have discovered this decades earlier. In 1917, French logician Jean Nicod discovered that it was possible to axiomatize propositional logic using the Sheffer stroke and only a single axiom schema and single inference rule.

The notion of a “truth table” is often utilized in the discussion of truth-functional connectives (discussed below). It seems to have been at least implicit in the work of Peirce, W. S. Jevons (1835-1882), Lewis Carroll (1832-1898), John Venn (1834-1923), and Allan Marquand (1853-1924). Truth tables appear explicitly in writings by Eugen Müller as early as 1909. Their use gained rapid popularity in the early 1920s, perhaps due to the combined influence of the work of Emil Post, whose 1921 work makes liberal use of them, and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s 1921 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, in which truth tables and truth-functionality are prominently featured.

Systematic inquiry into axiomatic systems for propositional logic and related metatheory was conducted in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s by David Hilbert, Paul Bernays, Alfred Tarski, Jan Łukasiewicz, Kurt Gödel, Alonzo Church, and others. It is during this period, that most of the important metatheoretic results such as those discussed in Section VII were discovered.

Complete natural deduction systems for classical truth-functional propositional logic were developed and popularized in the work of Gerhard Gentzen in the mid-1930s, and subsequently introduced into influential textbooks such as that of F. B. Fitch (1952) and Irving Copi (1953).

Modal propositional logics are the most widely studied form of non-truth-functional propositional logic. While interest in modal logic dates back to Aristotle, by contemporary standards the first systematic inquiry into this modal propositional logic can be found in the work of C. I. Lewis in 1912 and 1913. Among other well-known forms of non-truth-functional propositional logic, deontic logic began with the work of Ernst Mally in 1926, and epistemic logic was first treated systematically by Jaakko Hintikka in the early 1960s. The modern study of three-valued propositional logic began in the work of Jan Łukasiewicz in 1917, and other forms of non-classical propositional logic soon followed suit. Relevance propositional logic is relatively more recent; dating from the mid-1970s in the work of A. R. Anderson and N. D. Belnap. Paraconsistent logic, while having its roots in the work of Łukasiewicz and others, has blossomed into an independent area of research only recently, mainly due to work undertaken by N. C. A. da Costa, Graham Priest and others in the 1970s and 1980s.

3. The Language of Propositional Logic

The basic rules and principles of classical truth-functional propositional logic are, among contemporary logicians, almost entirely agreed upon, and capable of being stated in a definitive way. This is most easily done if we utilize a simplified logical language that deals only with simple statements considered as indivisible units as well as complex statements joined together by means of truth-functional connectives. We first consider a language called PL for “Propositional Logic”. Later we shall consider two even simpler languages, PL’ and PL”.

a. Syntax and Formation Rules of PL

In any ordinary language, a statement would never consist of a single word, but would always at the very least consist of a noun or pronoun along with a verb. However, because propositional logic does not consider smaller parts of statements, and treats simple statements as indivisible wholes, the language PL uses uppercase letters ‘A‘, ‘B‘, ‘C‘, etc., in place of complete statements. The logical signs ‘\land‘, ‘\lor‘, ‘→’, ‘↔’, and ‘\neg‘ are used in place of the truth-functional operators, “and”, “or”, “if… then…”, “if and only if”, and “not”, respectively. So, consider again the following example argument, mentioned in Section I.

Paris is the capital of France and Paris has a population of over two million.

Therefore, Paris has a population of over two million.

If we use the letter ‘C‘ as our translation of the statement “Paris is the captial of France” in PL, and the letter ‘P‘ as our translation of the statement “Paris has a population of over two million”, and use a horizontal line to separate the premise(s) of an argument from the conclusion, the above argument could be symbolized in language PL as follows:

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} C \land P\\<br />

\hline P<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

In addition to statement letters like ‘C‘ and ‘P‘ and the operators, the only other signs that sometimes appear in the language PL are parentheses which are used in forming even more complex statements. Consider the English compound sentence, “Paris is the most important city in France if and only if Paris is the capital of France and Paris has a population of over two million.” If we use the letter ‘I‘ in language PL to mean that Paris is the most important city in France, this sentence would be translated into PL as follows:

I \leftrightarrow (C \land P)

The parentheses are used to group together the statements ‘C‘ and ‘P‘ and differentiate the above statement from the one that would be written as follows:

(I \leftrightarrow C) \land P

This latter statement asserts that Paris is the most important city in France if and only if it is the capital of France, and (separate from this), Paris has a population of over two million. The difference between the two is subtle, but important logically.

It is important to describe the syntax and make-up of statements in the language PL in a precise manner, and give some definitions that will be used later on. Before doing this, it is worthwhile to make a distinction between the language in which we will be discussing PL, namely, English, from PL itself. Whenever one language is used to discuss another, the language in which the discussion takes place is called the metalanguage, and language under discussion is called the object language. In this context, the object language is the language PL, and the metalanguage is English, or to be more precise, English supplemented with certain special devices that are used to talk about language PL. It is possible in English to talk about words and sentences in other languages, and when we do, we place the words or sentences we wish to talk about in quotation marks. Therefore, using ordinary English, I can say that “parler” is a French verb, and “I \land C” is a statement of PL. The following expression is part of PL, not English:

(I \leftrightarrow C) \land P

However, the following expression is a part of English; in particular, it is the English name of a PL sentence:

“(I \leftrightarrow C) \land P”

This point may seem rather trivial, but it is easy to become confused if one is not careful.

In our metalanguage, we shall also be using certain variables that are used to stand for arbitrary expressions built from the basic symbols of PL. In what follows, the Greek letters ‘\alpha‘, ‘\beta‘, and so on, are used for any object language (PL) expression of a certain designated form. For example, later on, we shall say that, if \alpha is a statement of PL, then so is \ulcorner \neg \alpha \urcorner. Notice that ‘\alpha‘ itself is not a symbol that appears in PL; it is a symbol used in English to speak about symbols of PL. We will also be making use of so-called “Quine corners”, written ‘\ulcorner‘ and ‘\urcorner‘, which are a special metalinguistic device used to speak about object language expressions constructed in a certain way. Suppose \alpha is the statement “(I \leftrightarrow C)” and \beta is the statement “(P \land C)“; then \ulcorner \alpha \lor \beta \urcorner is the complex statement “(I \leftrightarrow C) \lor (P \land C)“.

Let us now proceed to giving certain definitions used in the metalanguage when speaking of the language PL.

Definition: A statement letter of PL is defined as any uppercase letter written with or without a numerical subscript.

Note: According to this definition, ‘A‘, ‘B‘, ‘B_2‘, ‘C_3‘, and ‘P_{14}‘ are examples of statement letters. The numerical subscripts are used just in case we need to deal with more than 26 simple statements: in that case, we can use ‘P_1‘ to mean something different than ‘P_2‘, and so forth.

Definition: A connective or operator of PL is any of the signs ‘\neg‘, ‘\land‘, ‘\lor‘, ‘→’, and ‘↔’.

Definition: A well-formed formula (hereafter abbreviated as wff) of PL is defined recursively as follows:

- Any statement letter is a well-formed formula.

- If \alpha is a well-formed formula, then so is \ulcorner \neg \alpha \urcorner.

- If \alpha and \beta are well-formed formulas, then so is \ulcorner (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner.

- If \alpha and \beta are well-formed formulas, then so is \ulcorner (\alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner.

- If \alpha and \beta are well-formed formulas, then so is \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner.

- If \alpha and \beta are well-formed formulas, then so is \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner.

- Nothing that cannot be constructed by successive steps of (1)-(6) is a well-formed formula.

Note: According to part (1) of this definition, the statement letters ‘C‘, ‘P‘ and ‘M‘ are wffs. Because ‘C‘ and ‘P‘ are wffs, by part (3), “(C \land P)” is a wff. Because it is a wff, and ‘M‘ is also a wff, by part (6), “(M \leftrightarrow (C \land P))” is a wff. It is conventional to regard the outermost parentheses on a wff as optional, so that “M \leftrightarrow (C \land P)” is treated as an abbreviated form of “(M \leftrightarrow (C \land P))“. However, whenever a shorter wff is used in constructing a more complicated wff, the parentheses on the shorter wff are necessary.

The notion of a well-formed formula should be understood as corresponding to the notion of a grammatically correct or properly constructed statement of language PL. This definition tells us, for example, that “\neg (Q \lor \neg R)” is grammatical for PL because it is a well-formed formula, whereas the string of symbols, “\neg Q \neg \lor ( \leftrightarrow P \land“, while consisting entirely of symbols used in PL, is not grammatical because it is not well-formed.

b. Truth Functions and Truth Tables

So far we have in effect described the grammar of language PL. When setting up a language fully, however, it is necessary not only to establish rules of grammar, but also describe the meanings of the symbols used in the language. We have already suggested that uppercase letters are used as complete simple statements. Because truth-functional propositional logic does not analyze the parts of simple statements, and only considers those ways of combining them to form more complicated statements that make the truth or falsity of the whole dependent entirely on the truth or falsity of the parts, in effect, it does not matter what meaning we assign to the individual statement letters like ‘P‘, ‘Q‘ and ‘R‘, etc., provided that each is taken as either true or false (and not both).

However, more must be said about the meaning or semantics, of the logical operators ‘\land‘, ‘\lor‘, ‘→’, ‘↔’, and ‘\neg‘. As mentioned above, these are used in place of the English words, ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘if… then…’, ‘if and only if’, and ‘not’, respectively. However, the correspondence is really only rough, because the operators of PL are considered to be entirely truth-functional, whereas their English counterparts are not always used truth-functionally. Consider, for example, the following statements:

- If Bob Dole is president of the United States in 2004, then the president of the United States in 2004 is a member of the Republican party.

- If Al Gore is president of the United States in 2004, then the president of the United States in 2004 is a member of the Republican party.

For those familiar with American politics, it is tempting to regard the English sentence (1) as true, but to regard (2) as false, since Dole is a Republican but Gore is not. But notice that in both cases, the simple statement in the “if” part of the “if… then…” statement is false, and the simple statement in the “then” part of the statement is true. This shows that the English operator “if… then…” is not fully truth-functional. However, all the operators of language PL are entirely truth-functional, so the sign ‘→’, though similar in many ways to the English “if… then…” is not in all ways the same. More is said about this operator below.

Since our study is limited to the ways in which the truth-values of complex statements depend on the truth-values of the parts, for each operator, the only aspect of its meaning relevant in this context is its associated truth-function. The truth-function for an operator can be represented as a table, each line of which expresses a possible combination of truth-values for the simpler statements to which the operator applies, along with the resulting truth-value for the complex statement formed using the operator.

The signs ‘\land‘, ‘\lor‘, ‘→’, ‘↔’, and ‘\neg‘, correspond, respectively, to the truth-functions of conjunction, disjunction, material implication, material equivalence, and negation. We shall consider these individually.

Conjunction: The conjunction of two statements \alpha and \beta, written in PL as \ulcorner (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner, is true if both \alpha and \beta are true, and is false if either \alpha is false or \beta is false or both are false. In effect, the meaning of the operator ‘\land‘ can be displayed according to the following chart, which shows the truth-value of the conjunction depending on the four possibilities of the truth-values of the parts:

| \alpha |

\beta |

(\alpha \land \beta) |

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

F

F

F

|

Conjunction using the operator ‘\land‘ is language PL’s rough equivalent of joining statements together with ‘and’ in English. In a statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner, the two statements joined together, \alpha and \beta, are called the conjuncts, and the whole statement is called a conjunction.

Instead of the sign ‘\land‘, some other logical works use the signs ‘\&‘ or ‘\bullet‘ for conjunction.

Disjunction: The disjunction of two statements \alpha and \beta, written in PL as \ulcorner (\alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner, is true if either \alpha is true or \beta is true, or both \alpha and \beta are true, and is false only if both \alpha and \beta are false. A chart similar to that given above for conjunction, modified for to show the meaning of the disjunction sign ‘\lor‘ instead, would be drawn as follows:

| \alpha |

\beta |

(\alpha \lor \beta) |

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

T

T

F

|

This is language PL’s rough equivalent of joining statements together with the word ‘or’ in English. However, it should be noted that the sign ‘\lor‘ is used for disjunction in the inclusive sense. Sometimes when the word ‘or’ is used to join together two English statements, we only regard the whole as true if one side or the other is true, but not both, as when the statement “Either we can buy the toy robot, or we can buy the toy truck; you must choose!” is spoken by a parent to a child who wants both toys. This is called the exclusive sense of ‘or’. However, in PL, the sign ‘\lor‘ is used inclusively, and is more analogous to the English word ‘or’ as it appears in a statement such as (for example, said about someone who has just received a perfect score on the SAT), “either she studied hard, or she is extremely bright”, which does not mean to rule out the possibility that she both studied hard and is bright. In a statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner, the two statements joined together, \alpha and \beta, are called the disjuncts, and the whole statement is called a disjunction.

Material Implication: This truth-function is represented in language PL with the sign ‘→’. A statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner, is false if \alpha is true and \beta is false, and is true if either \alpha is false or \beta is true (or both). This truth-function generates the following chart:

| \alpha |

\beta |

(\alpha \rightarrow \beta) |

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

F

T

T

|

Because the truth of a statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner rules out the possibility of \alpha being true and \beta being false, there is some similarity between the operator ‘→’ and the English phrase, “if… then…”, which is also used to rule out the possibility of one statement being true and another false; however, ‘→’ is used entirely truth-functionally, and so, for reasons discussed earlier, it is not entirely analogous with “if… then…” in English. If \alpha is false, then \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner is regarded as true, whether or not there is any connection between the falsity of \alpha and the truth-value of \beta. In a statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner, we call \alpha the antecedent, and we call \beta the consequent, and the whole statement \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner is sometimes also called a (material) conditional.

The sign ‘\supset‘ is sometimes used instead of ‘→’ for material implication.

Material Equivalence: This truth-function is represented in language PL with the sign ‘↔’. A statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner is regarded as true if \alpha and \beta are either both true or both false, and is regarded as false if they have different truth-values. Hence, we have the following chart:

| \alpha |

\beta |

(\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) |

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

F

F

T

|

Since the truth of a statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner requires \alpha and \beta to have the same truth-value, this operator is often likened to the English phrase “…if and only if…”. Again, however, they are not in all ways alike, because ‘↔’ is used entirely truth-functionally. Regardless of what \alpha and \beta are, and what relation (if any) they have to one another, if both are false, \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner is considered to be true. However, we would not normally regard the statement “Al Gore is the President of the United States in 2004 if and only if Bob Dole is the President of the United States in 2004” as true simply because both simpler statements happen to be false. A statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner is also sometimes referred to as a (material) biconditional.

The sign ‘\equiv‘ is sometimes used instead of ‘↔’ for material equivalence.

Negation: The negation of statement \alpha, simply written \ulcorner \neg \alpha \urcorner in language PL, is regarded as true if \alpha is false, and false if \alpha is true. Unlike the other operators we have considered, negation is applied to a single statement. The corresponding chart can therefore be drawn more simply as follows:

| \alpha |

\neg \alpha |

T

F |

F

T |

The negation sign ‘\neg‘ bears obvious similarities to the word ‘not’ used in English, as well as similar phrases used to change a statement from affirmative to negative or vice-versa. In logical languages, the signs ‘\sim‘ or ‘-‘ are sometimes used in place of ‘\neg‘.

The five charts together provide the rules needed to determine the truth-value of a given wff in language PL when given the truth-values of the independent statement letters making it up. These rules are very easy to apply in the case of a very simple wff such as “(P \land Q)“. Suppose that ‘P‘ is true, and ‘Q‘ is false; according to the second row of the chart given for the operator, ‘\land‘, we can see that this statement is false.

However, the charts also provide the rules necessary for determining the truth-value of more complicated statements. We have just seen that “(P \land Q)” is false if ‘P‘ is true and ‘Q‘ is false. Consider a more complicated statement that contains this statement as a part, for example, “((P \land Q) \rightarrow \neg R)“, and suppose once again that ‘P‘ is true, and ‘Q‘ is false, and further suppose that ‘R‘ is also false. To determine the truth-value of this complicated statement, we begin by determining the truth-value of the internal parts. The statement “(P \land Q)“, as we have seen, is false. The other substatement, “\neg R“, is true, because ‘R‘ is false, and ‘\neg‘ reverses the truth-value of that to which it is applied. Now we can determine the truth-value of the whole wff, “((P \land Q) \rightarrow \neg R)“, by consulting the chart given above for ‘→’. Here, the wff “(P \land Q)” is our \alpha, and “\neg R” is our \beta, and since their truth-values are F and T, respectively, we consult the third row of the chart, and we see that the complex statement “((P \land Q) \rightarrow \neg R)” is true.

We have so far been considering the case in which ‘P‘ is true and ‘Q‘ and ‘R‘ are both false. There are, however, a number of other possibilities with regard to the possible truth-values of the statement letters, ‘P‘, ‘Q‘ and ‘R‘. There are eight possibilities altogether, as shown by the following list:

|

P

|

Q

|

R

|

|

T

T

T

T

F

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

T

F

T

F

|

Strictly speaking, each of the eight possibilities above represents a different truth-value assignment, which can be defined as a possible assignment of truth-values T or F to the different statement letters making up a wff or series of wffs. If a wff has n distinct statement letters making up, the number of possible truth-value assignments is 2n. With the wff, “((P \land Q) \rightarrow \neg R)“, there are three statement letters, ‘P‘, ‘Q‘ and ‘R‘, and so there are 8 truth-value assignments.

It then becomes possible to draw a chart showing how the truth-value of a given wff would be resolved for each possible truth-value assignment. We begin with a chart showing all the possible truth-value assignments for the wff, such as the one given above. Next, we write out the wff itself on the top right of our chart, with spaces between the signs. Then, for each, truth-value assignment, we repeat the appropriate truth-value, ‘T’, or ‘F’, underneath the statement letters as they appear in the wff. Then, as the truth-values of those wffs that are parts of the complete wff are determined, we write their truth-values underneath the logical sign that is used to form them. The final column filled in shows the truth-value of the entire statement for each truth-value assignment. Given the importance of this column, we highlight it in some way. Here, we highlight it in yellow.

|

P

|

Q

|

R

|

| |

((P

|

\land

|

Q)

|

→

|

\neg

|

R)

|

|

T

T

T

T

F

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

T

T

F

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

F

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

T

T

F

F

|

F

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

|

F

T

F

T

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

T

F

T

F

|

Charts such as the one given above are called truth tables. In classical truth-functional propositional logic, a truth table constructed for a given wff in effects reveals everything logically important about that wff. The above chart tells us that the wff “((P \land Q) \rightarrow \neg R)” can only be false if ‘P‘, ‘Q‘ and ‘R‘ are all true, and is true otherwise.

c. Definability of the Operators and the Languages PL’ and PL”

The language PL, as we have seen, contains operators that are roughly analogous to the English operators ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘if… then…’, ‘if and only if’, and ‘not’. Each of these, as we have also seen, can be thought of as representing a certain truth-function. It might be objected however, that there are other methods of combining statements together in which the truth-value of the statement depends wholly on the truth-values of the parts, or in other words, that there are truth-functions besides conjunction, (inclusive) disjunction, material implication, material equivalence and negation. For example, we noted earlier that the sign ‘\lor‘ is used analogously to ‘or’ in the inclusive sense, which means that language PL has no simple sign for ‘or’ in the exclusive sense. It might be thought, however, that the langauge PL is incomplete without the addition of an additional symbol, say ‘\veebar‘, such that \ulcorner (\alpha \veebar \beta) \urcorner would be regarded as true if \alpha is true and \beta is false, or \alpha is false and \beta is true, but would be regarded as false if either both \alpha and \beta are true or both \alpha and \beta are false.

However, a possible response to this objection would be to make note that while language PL does not include a simple sign for this exclusive sense of disjunction, it is possible, using the symbols that are included in PL, to construct a statement that is true in exactly the same circumstances. Consider, for example, a statement of the form \ulcorner \neg (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner. It is easily shown, using a truth table, that any wff of this form would have the same truth-value as a would-be statement using the operator ‘\veebar‘. See the following chart:

|

\alpha

|

\beta

|

| |

\neg

|

(\alpha

|

↔

|

\beta)

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

F

T

T

F

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

Here we see that a wff of the form \ulcorner \neg (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner is true if either \alpha or \beta is true but not both. This shows that PL is not lacking in any way by not containing a sign ‘\veebar‘. All the work that one would wish to do with this sign can be done using the signs ‘↔’ and ‘\neg‘. Indeed, one might claim that the sign ‘\veebar‘ can be defined in terms of the signs ‘↔’, and ‘\neg‘, and then use the form \ulcorner (\alpha \veebar \beta) \urcorner as an abbreviation of a wff of the form \ulcorner \neg (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner, without actually expanding the primitive vocabulary of language PL.

The signs ‘\land‘, ‘\lor‘, ‘→’, ‘↔’ and ‘\neg‘, were chosen as the operators to include in PL because they correspond (roughly) the sorts of truth-functional operators that are most often used in ordinary discourse and reasoning. However, given the preceding discussion, it is natural to ask whether or not some operators on this list can be defined in terms of the others. It turns out that they can. In fact, if for some reason we wished our logical language to have a more limited vocabulary, it is possible to get by using only the signs ‘\neg‘ and ‘→’, and define all other possible truth-functions in virtue of them. Consider, for example, the following truth table for statements of the form \ulcorner \neg (\alpha \rightarrow \neg \beta) \urcorner:

|

\alpha

|

\beta

|

| |

\neg

|

(\alpha

|

→

|

\neg

|

\beta)

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

|

F

T

T

T

|

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

We can see from the above that a wff of the form \ulcorner \neg (\alpha \rightarrow \neg \beta) \urcorner always has the same truth-value as the corresponding statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner. This shows that the sign ‘\land‘ can in effect be defined using the signs ‘\neg‘ and ‘→’.

Next, consider the truth table for statements of the form \ulcorner (\neg \alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner:

|

\alpha

|

\beta

|

| |

(\neg

|

\alpha

|

→

|

\beta)

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

F

F

T

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

T

T

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

Here we can see that a statement of the form \ulcorner (\neg \alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner always has the same truth-value as the corresponding statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner. Again, this shows that the sign ‘\lor‘ could in effect be defined using the signs ‘→’ and ‘\neg‘.

Lastly, consider the truth table for a statement of the form \ulcorner \neg (( \alpha \rightarrow \beta) \rightarrow \neg (\beta \rightarrow \alpha)) \urcorner:

|

\alpha

|

\beta

|

| |

\neg

|

((\alpha

|

→

|

\beta)

|

→

|

\neg

|

(\beta

|

→

|

\alpha))

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

F

F

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

T

T

F

|

F

F

T

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

T

F

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

From the above, we see that a statement of the form \ulcorner \neg (( \alpha \rightarrow \beta) \rightarrow \neg (\beta \rightarrow \alpha)) \urcorner always has the same truth-value as the corresponding statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner. In effect, therefore, we have shown that the remaining operators of PL can all be defined in virtue of ‘→’, and ‘\neg‘, and that, if we wished, we could do away with the operators, ‘\land‘, ‘\lor‘ and ‘↔’, and simply make do with those equivalent expressions built up entirely from ‘→’ and ‘\neg‘.

Let us call the language that results from this simplication PL’. While the definition of a statement letter remains the same for PL’ as for PL, the definition of a well-formed formula (wff) for PL’ can be greatly simplified. In effect, it can be stated as follows:

Definition: A well-formed formula (or wff) of PL’ is defined recursively as follows:

- Any statement letter is a well-formed formula.

- If \alpha is a well-formed formula, then so is \ulcorner \neg \alpha \urcorner.

- If \alpha and \beta are well-formed formulas, then so is \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner.

- Nothing that cannot be constructed by successive steps of (1)-(3) is a well-formed formula.

Strictly speaking, then, the langauge PL’ does not contain any statements using the operators ‘\lor‘, ‘\land‘, or ‘↔’. One could however, utilize conventions such that, in language PL’, an expression of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner is to be regarded as a mere abbreviation or short-hand for the corresponding statement of the form \ulcorner \neg (\alpha \rightarrow \neg \beta) \urcorner, and similarly that expressions of the forms \ulcorner (\alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner and \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner are to be regarded as abbreviations of expressions of the forms \ulcorner (\neg \alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner or \ulcorner \neg (( \alpha \rightarrow \beta) \rightarrow \neg (\beta \rightarrow \alpha)) \urcorner, respectively. In effect, this means that it is possible to translate any wff of language PL into an equivalent wff of language PL’.

In Section VII, it is proven that not only are the operators ‘\neg‘ and ‘→’ sufficient for defining every truth-functional operator included in language PL, but also that they are sufficient for defining any imaginable truth-functional operator in classical propositional logic.

Nevertheless, the choice of ‘\neg‘ and ‘→’ for the primitive signs used in language PL’ is to some extent arbitrary. It would also have been possible to define all other operators of PL (including ‘→’) using the signs ‘\neg‘ and ‘\lor‘. On this approach, \ulcorner (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner \neg (\neg \alpha \lor \neg \beta) \urcorner, \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner (\neg \alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner, and \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner \neg (\neg(\neg \alpha \lor \beta) \lor \neg (\neg \beta \lor \alpha)) \urcorner. Similarly, we could instead have begun with ‘\neg‘ and ‘\land‘ as our starting operators. On this way of proceeding, \ulcorner (\alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner \neg (\neg \alpha \land \neg \beta) \urcorner, \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner \neg (\alpha \land \neg \beta) \urcorner, and \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner (\neg (\alpha \land \neg \beta) \land \neg (\beta \land \neg \alpha) \urcorner.

There are, as we have seen, multiple different ways of reducing all truth-functional operators down to two primitives. There are also two ways of reducing all truth-functional operators down to a single primitive operator, but they require using an operator that is not included in language PL as primitive. On one approach, we utilize an operator written ‘|’, and explain the truth-function corresponding to this sign by means of the following chart:

| \alpha |

\beta |

(\alpha | \beta) |

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

T

T

T

|

Here we can see that a statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha | \beta) \urcorner is false if both \alpha and \beta are true, and true otherwise. For this reason one might read ‘|’ as akin to the English expression, “Not both … and …”. Indeed, it is possible to represent this truth-function in language PL using an expression of the form, \ulcorner \neg (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner. However, since it is our intention to show that all other truth-functional operators, including ‘\neg‘ and ‘\land‘ can be derived from ‘|’, it is better not to regard the meanings of ‘\neg‘ and ‘\land‘ as playing a part of the meaning of ‘|’, and instead attempt (however counterintuitive it may seem) to regard ‘|’ as conceptually prior to ‘\neg‘ and ‘\land‘.

The sign ‘|’ is called the Sheffer stroke, and is named after H. M. Sheffer, who first publicized the result that all truth-functional connectives could be defined in virtue of a single operator in 1913.

We can then see that the connective ‘\land‘ can be defined in virtue of ‘|’, because an expression of the form \ulcorner ((\alpha | \beta) | (\alpha | \beta)) \urcorner generates the following truth table, and hence is equivalent to the corresponding expression of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner:

|

\alpha

|

\beta

|

| |

((\alpha

|

|

|

\beta)

|

|

|

(\alpha

|

|

|

\beta))

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

F

T

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

|

F

T

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

Similarly, we can define the operator ‘\lor‘ using ‘|’ by noting that an expression of the form \ulcorner ((\alpha | \alpha) | (\beta | \beta)) \urcorner always has the same truth-value as the corresponding statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner:

|

\alpha

|

\beta

|

| |

((\alpha

|

|

|

\alpha)

|

|

|

(\beta

|

|

|

\beta))

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

F

F

T

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

T

T

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

The following truth table shows that a statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha | (\beta | \beta)) \urcorner always has the same truth table as a statement of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \rightarrow \beta) \urcorner:

|

\alpha

|

\beta

|

| |

(\alpha

|

|

|

(\beta

|

|

|

\beta))

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

Although far from intuitively obvious, the following table shows that an expression of the form \ulcorner (((\alpha | \alpha) | (\beta | \beta)) | (\alpha | \beta)) \urcorner always has the same truth-value as the corresponding wff of the form \ulcorner (\alpha \leftrightarrow \beta) \urcorner:

|

\alpha

|

\beta

|

| |

(((\alpha

|

|

|

\alpha)

|

|

|

(\beta

|

|

|

\beta))

|

|

|

(\alpha

|

|

|

\beta))

|

|

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

F

F

T

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

T

T

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

F

F

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

F

T

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

This leaves only the sign ‘\neg‘, which is perhaps the easiest to define using ‘|’, as clearly \ulcorner (\alpha | \alpha) \urcorner, or, roughly, “not both \alpha and \alpha“, has the opposite truth-value from \alpha itself:

|

\alpha

|

| |

(\alpha

|

|

|

\alpha)

|

|

|

|

T

F

|

F

T

|

T

F

|

If, therefore, we desire a language for use in studying propositional logic that has as small a vocabulary as possible, we might suggest using a language that employs the sign ‘|’ as its sole primitive operator, and defines all other truth-functional operators in virtue of it. Let us call such a language PL”. PL” differs from PL and PL’ only in that its definition of a well-formed formula can be simplified even further:

Definition: A well-formed formula (or wff) of PL” is defined recursively as follows:

- Any statement letter is a well-formed formula.

- If \alpha and \beta are well-formed formulas, then so is \ulcorner (\alpha | \beta) \urcorner.

- Nothing that cannot be constructed by successive steps of (1)-(2) is a well-formed formula.

In language PL”, strictly speaking, ‘|’ is the only operator. However, for reasons that should be clear from the above, any expression from language PL that involves any of the operators ‘\neg‘, ‘\land‘, ‘\lor‘, ‘→’, or ‘↔’ could be translated into language PL” without the loss of any of its important logical properties. In effect, statements using these signs could be regarded as abbreviations or shorthand expressions for wffs of PL” that only use the operator ‘|’.

Even here, the choice of ‘|’ as the sole primitive is to some extent arbitrary. It would also be possible to reduce all truth-functional operators down to a single primitive by making use of a sign ‘\downarrow‘, treating it as roughly equivalent to the English expression, “neither … nor …”, so that the corresponding chart would be drawn as follows:

| \alpha |

\beta |

(\alpha \downarrow \beta) |

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

F

F

T

|

If we were to use ‘\downarrow‘ as our sole operator, we could again define all the others. \ulcorner \neg \alpha \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner (\alpha \downarrow \alpha) \urcorner; \ulcorner (\alpha \lor \beta) \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner ((\alpha \downarrow \beta) \downarrow (\alpha \downarrow \beta)) \urcorner; \ulcorner (\alpha \land \beta) \urcorner would be defined as \ulcorner ((\alpha \downarrow \alpha) \downarrow (\beta \downarrow \beta)) \urcorner; and similarly for the other operators. The sign ‘\downarrow‘ is sometimes also referred to as the Sheffer stroke, and is also called the Peirce/Sheffer dagger.

Depending on one’s purposes in studying propositional logic, sometimes it makes sense to use a rich language like PL with more primitive operators, and sometimes it makes sense to use a relatively sparse language such as PL’ or PL” with fewer primitive operators. The advantage of the former approach is that it conforms better with our ordinary reasoning and thinking habits; the advantage of the latter is that it simplifies the logical language, which makes certain interesting results regarding the deductive systems making use of the language easier to prove.

For the remainder of this article, we shall primarily be concerned with the logical properties of statements formed in the richer language PL. However, we shall consider a system making use of language PL’ in some detail in Section VI, and shall also make brief mention of a system making use of language PL”.

4. Tautologies, Logical Equivalence and Validity

Truth-functional propositional logic concerns itself only with those ways of combining statements to form more complicated statements in which the truth-values of the complicated statements depend entirely on the truth-values of the parts. Owing to this, all those features of a complex statement that are studied in propositional logic derive from the way in which their truth-values are derived from those of their parts. These features are therefore always represented in the truth table for a given statement.

Some complex statements have the interesting feature that they would be true regardless of the truth-values of the simple statements making them up. A simple example would be the wff “P \lor \neg P“; that is, “P or not P“. It is fairly easy to see that this statement is true regardless of whether ‘P‘ is true or ‘P‘ is false. This is also shown by its truth table:

|

P

|

| |

P

|

\lor

|

\neg

|

P

|

|

|

|

T

F

|

T

T

|

F

T

|

T

F

|

There are, however, statements for which this is true but it is not so obvious. Consider the wff, “R \rightarrow ((P \rightarrow Q) \lor \neg (R \rightarrow Q))“. This wff also comes out as true regardless of the truth-values of ‘P‘, ‘Q‘ and ‘R‘.

|

P

|

Q

|

R

|

| |

R

|

→

|

((P

|

→

|

Q)

|

\lor

|

\neg

|

(R

|

→

|

Q))

|

|

T

T

T

T

F

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

F

T

F

T

F

T

F

|

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

T

|

T

T

T

T

F

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

T

T

T

T

|

T

T

F

F

T

T

F

F

|

T

T

T

F

T

T

T

T

|

F

F

T

F

F

F

T

F

|

T

F

T

F

T

F

T

F

|

T

T

F

T

T

T

F

T

|

T

T

F

F

T

T

F

F

|

Statements that have this interesting feature are called tautologies. Let us define this notion precisely.

Definition: a wff is a tautology if and only if it is true for all possible truth-value assignments to the statement letters making it up.

Tautologies are also sometimes called logical truths or truths of logic because tautologies can be recognized as true solely in virtue of the principles of propositional logic, and without recourse to any additional information.

On the other side of the spectrum from tautologies are statements that come out as false regardless of the truth-values of the simple statements making them up. A simple example of such a statement would be the wff “P \land \neg P“; clearly such a statement cannot be true, as it contradicts itself. This is revealed by its truth table:

|

P

|

| |

P

|

\land

|

\neg

|

P

|

|

|

|

T

F

|

F

F

|

F

T

|

T

F

|

To state this precisely:

Definition: a wff is a self-contradiction if and only if it is false for all possible truth-value assignments to the statement letters making it up.

Another, more interesting, example of a self-contradiction is the statement “\neg (P \rightarrow Q) \land \neg (Q \rightarrow P)“; this is not as obviously self-contradictory. However, we can see that it is when we consider its truth table:

|

P

|

Q

|

| |

\neg

|

(P

|

→

|

Q)

|

\land

|

\neg

|

(Q

|

→

|

P)

|

|

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

F

T

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

F

F

F

|

F

F

T

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

T

F

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

A statement that is neither self-contradictory nor tautological is called a contingent statement. A contingent statement is true for some truth-value assignments to its statement letters and false for others. The truth table for a contingent statement reveals which truth-value assignments make it come out as true, and which make it come out as false. Consider the truth table for the statement “(P \rightarrow Q) \land (P \rightarrow \neg Q)“:

|

P

|

Q

|

| |

(P

|

→

|

Q)

|

\land

|

(P

|

→

|

\neg

|

Q)

|

|

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

F

T

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

F

T

T

T

|

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

We can see that of the four possible truth-value assignments for this statement, two make it come as true, and two make it come out as false. Specifically, the statement is true when ‘P‘ is false and ‘Q‘ is true, and when ‘P‘ is false and ‘Q‘ is false, and the statement is false when ‘P‘ is true and ‘Q‘ is true and when ‘P‘ is true and ‘Q‘ is false.

Truth tables are also useful in studying logical relationships that hold between two or more statements. For example, two statements are said to be consistent when it is possible for both to be true, and are said to be inconsistent when it is not possible for both to be true. In propositional logic, we can make this more precise as follows.

Definition: two wffs are consistent if and only if there is at least one possible truth-value assignment to the statement letters making them up that makes both wffs true.

Definition: two wffs are inconsistent if and only if there is no truth-value assignment to the statement letters making them up that makes them both true.

Whether or not two statements are consistent can be determined by means of a combined truth table for the two statements. For example, the two statements, “P \lor Q” and “\neg (P \leftrightarrow \neg Q)” are consistent:

|

P

|

Q

|

| |

P

|

\lor

|

Q

|

|

\neg

|

(P

|

↔

|

\neg

|

Q)

|

|

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

T

T

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

F

F

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

F

T

T

F

|

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

Here, we see that there is one truth-value assignment, that in which both ‘P‘ and ‘Q‘ are true, that makes both “P \lor Q” and “\neg (P \leftrightarrow \neg Q)” true. However, the statements “(P \rightarrow Q) \land P” and “\neg (Q \lor \neg P)” are inconsistent, because there is no truth-value assignment in which both come out as true.

|

P

|

Q

|

| |

(P

|

→

|

Q)

|

\land

|

P

|

|

\neg

|

(Q

|

\lor

|

\neg

|

P))

|

|

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

F

F

F

|

T

T

F

F

|

|

F

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

F

T

T

|

F

F

T

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

Another relationship that can hold between two statements is that of having the same truth-value regardless of the truth-values of the simple statements making them up. Consider a combined truth table for the wffs “\neg P \rightarrow \neg Q” and “\neg (Q \land \neg P)“:

|

P

|

Q

|

| |

\neg

|

P

|

→

|

\neg

|

Q

|

|

\neg

|

(Q

|

\land

|

\neg

|

P))

|

|

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

F

F

T

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

T

F

T

|

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

F

F

T

F

|

F

F

T

T

|

T

T

F

F

|

Here we see that these two statements necessarily have the same truth-value.

Definition: two statements are said to be logically equivalent if and only if all possible truth-value assignments to the statement letters making them up result in the same resulting truth-values for the whole statements.

The above statements are logically equivalent. However, the truth table given above for the statements “P \lor Q” and “\neg (P \leftrightarrow \neg Q)” show that they, on the other hand, are not logically equivalent, because they differ in truth-value for three of the four possible truth-value assignments.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, truth tables can be utilized to determine whether or not an argument is logically valid. In general, an argument is said to be logically valid whenever it has a form that makes it impossible for the conclusion to be false if the premises are true. (See the encyclopedia article on “Validity and Soundness“.) In classical propositional logic, we can give this a more precise characterization.

Definition: a wff \beta is said to be a logical consequence of a set of wffs \alpha_1, \alpha_2, ..., \alpha_n, if and only if there is no truth-value assignment to the statement letters making up these wffs that makes all of \alpha_1, \alpha_2, ..., \alpha_n true but does not make \beta true.

An argument is logically valid if and only if its conclusion is a logical consequence of its premises. If an argument whose conclusion is \beta and whose only premise is \alpha is logically valid, then \alpha is said to logically imply \beta.

For example, consider the following argument:

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} P \rightarrow Q\\<br />

\neg Q \rightarrow P\\<br />

\hline Q<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

We can test the validity of this argument by constructing a combined truth table for all three statements.

|

P

|

Q

|

| |

P

|

→

|

Q

|

|

\neg

|

Q

|

→

|

P

|

|

Q

|

|

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

T

T

F

F

|

T

F

T

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

|

F

T

F

T

|

T

F

T

F

|

T

T

T

F

|

T

T

F

F

|

|

T

F

T

F

|

Here we see that both premises come out as true in the case in which both ‘P‘ and ‘Q‘ are true, and in which ‘P‘ is false but ‘Q‘ is true. However, in those cases, the conclusion is also true. It is possible for the conclusion to be false, but only if one of the premises is false as well. Hence, we can see that the inference represented by this argument is truth-preserving. Contrast this with the following example:

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} P \rightarrow Q\\<br />

\hline \neg Q \lor \neg P<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

Consider the truth-value assignment making both ‘P‘ and ‘Q‘ true. If we were to fill in that row of the truth-value for these statements, we would see that “P \rightarrow Q” comes out as true, but “\neg Q \lor \neg P” comes out as false. Even if ‘P‘ and ‘Q‘ are not actually both true, it is possible for them to both be true, and so this form of reasoning is not truth-preserving. In other words, the argument is not logically valid, and its premise does not logically imply its conclusion.

One of the most striking features of truth tables is that they provide an effective procedure for determining the logical truth, or tautologyhood of any single wff, and for determining the logical validity of any argument written in the language PL. The procedure for constructing such tables is purely rote, and while the size of the tables grows exponentially with the number of statement letters involved in the wff(s) under consideration, the number of rows is always finite and so it is in principle possible to finish the table and determine a definite answer. In sum, classical propositional logic is decidable.

5. Deduction: Rules of Inference and Replacement

a. Natural Deduction

Truth tables, as we have seen, can theoretically be used to solve any question in classical truth-functional propositional logic. However, this method has its drawbacks. The size of the tables grows exponentially with the number of distinct statement letters making up the statements involved. Moreover, truth tables are alien to our normal reasoning patterns. Another method for establishing the validity of an argument exists that does not have these drawbacks: the method of natural deduction. In natural deduction an attempt is made to reduce the reasoning behind a valid argument to a series of steps each of which is intuitively justified by the premises of the argument or previous steps in the series.

Consider the following argument stated in natural language:

Either cat fur or dog fur was found at the scene of the crime. If dog fur was found at the scene of the crime, officer Thompson had an allergy attack. If cat fur was found at the scene of the crime, then Macavity is responsible for the crime. But officer Thompson didn’t have an allergy attack, and so therefore Macavity must be responsible for the crime.

The validity of this argument can be made more obvious by representing the chain of reasoning leading from the premises to the conclusion:

- Either cat fur was found at the scene of the crime, or dog fur was found at the scene of the crime. (Premise)

- If dog fur was found at the scene of the crime, then officer Thompson had an allergy attack. (Premise)

- If cat fur was found at the scene of the crime, then Macavity is responsible for the crime. (Premise)

- Officer Thompson did not have an allergy attack. (Premise)

- Dog fur was not found at the scene of the crime. (Follows from 2 and 4.)

- Cat fur was found at the scene of the crime. (Follows from 1 and 5.)

- Macavity is responsible for the crime. (Conclusion. Follows from 3 and 6.)

Above, we do not jump directly from the premises to the conclusion, but show how intermediate inferences are used to ultimately justify the conclusion by a step-by-step chain. Each step in the chain represents a simple, obviously valid form of reasoning. In this example, the form of reasoning exemplified in line 5 is called modus tollens, which involves deducing the negation of the antecedent of a conditional from the conditional and the negation of its consequent. The form of reasoning exemplified in step 5 is called disjunctive syllogism, and involves deducing one disjunct of a disjunction on the basis of the disjunction and the negation of the other disjunct. Lastly, the form of reasoning found at line 7 is called modus ponens, which involves deducing the truth of the consequent of a conditional given truth of both the conditional and its antecedent. “Modus ponens” is Latin for affirming mode, and “modus tollens” is Latin for denying mode.

A system of natural deduction consists in the specification of a list of intuitively valid rules of inference for the construction of derivations or step-by-step deductions. Many equivalent systems of deduction have been given for classical truth-functional propositional logic. In what follows, we sketch one system, which is derived from the popular textbook by Irving Copi (1953). The system makes use of the language PL.

b. Rules of Inference

Here we give a list of intuitively valid rules of inference. The rules are stated in schematic form. Any inference in which any wff of language PL is substituted unformly for the schematic letters in the forms below constitutes an instance of the rule.

Modus ponens (MP):

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \alpha \rightarrow \beta, \alpha\\<br />

\hline \beta<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

(Modus ponens is sometimes also called “modus ponendo ponens”, “detachment” or a form of “→-elimination”.)

Modus tollens (MT):

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \alpha \rightarrow \beta, \neg \beta\\<br />

\hline \neg \alpha<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

(Modus tollens is sometimes also called “modus tollendo tollens” or a form of “→-elimination”.)

Disjunctive syllogism (DS): (two forms)

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \alpha \lor \beta, \neg \alpha\\<br />

\hline \beta<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \alpha \lor \beta, \neg \beta\\<br />

\hline \alpha<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

(Disjunctive syllogism is sometimes also called “modus tollendo ponens” or “\lor-elimination”.)

Addition (Add): (two forms)

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \alpha\\<br />

\hline \alpha \lor \beta<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \beta\\<br />

\hline \alpha \lor \beta<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

(Addition is sometimes also called “disjunction introduction” or “\lor–introduction”.)

Simplification (Simp): (two forms)

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \alpha \land \beta\\<br />

\hline \alpha<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \alpha \land \beta\\<br />

\hline \beta<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)

(Simplification is sometimes also called “conjunction elimination” or “\land-elimination”.)

Conjunction (Conj):

\(<br />

\begin{array}{l} \alpha, \beta\\<br />

\hline \alpha \land \beta<br />

\end{array}<br />

\)