Eternalism

Eternalism is a metaphysical view regarding the nature of time. It posits the equal existence of all times: the past, the present, and the future. Every event, from the big bang to the heat death of the universe, including our births and deaths, is equally real.

Under standard eternalism, temporal locations are somewhat akin to spatial locations. No place is exclusively real. When someone says that they stand ‘here’, it is clear that the term ‘here’ refers to their position. ‘Back’ and ‘front’ exist as well. Eternalists stress that ‘now’ is indexical in a similar way. It is equally real with ‘past’ and ‘future’. Events are classified as past, present, or future from some perspective.

Eternalism is contrasted with presentism, which maintains that only present things exist and with the growing block view (also known as possibilism or no-futurism), which holds that past and present things exist but not future ones. The moving spotlight view suggests that all times exist but that the present is the only actual time. This view can be termed eternalist, but it preserves a non-perspectival difference between past, present, and future by treating tense as absolute. Additionally, the moving spotlight view retains some characteristics of presentism by maintaining that the ‘now’ is unique and privileged.

Broadly speaking, presentism is a common-sensical view, and so aligns with our manifest image of time. This view is, however, at odds with the scientific image of time. The primary motivation for eternalism arises from orthodox interpretations of the theories of relativity. According to them, simultaneity is relative, not absolute. This implies that there is no universal ‘now’ stretched out across the entire universe. One observer’s present can be another’s past or future. Assuming the universe is four-dimensional spacetime, then all events exist unconditionally.

The classical argument for eternalism was devised in the 1960s by Rietdijk in 1966 and Putnam in 1967, with subsequent follow-ups by Maxwell in 1985, Penrose in 1989, and Peterson and Silberstein in 2010. This argument and its ramifications remain the subject of ongoing debate. They shall be further explored in this article, including their relation to other issues in the metaphysics of time and the philosophy of physics.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Classical Argument for Eternalism

- Eternalism in Relation to Other Metaphysical Issues

- Objections

- References and Further Reading

1. Introduction

a. Motivation

It is usually thought that presentism and perhaps the growing block view are a better match with our common-sensical idea of time than eternalism. It is obvious that the present is different from the past and the future. As you are presently reading these sentences, your reading is real. At least it is real in comparison to what you did a long time ago or will do a long time from now. There is, however, a problem. If the ‘now’ is exclusively real, that moment is entirely universal. The ‘now’— the moment your eyes skim through these lines— is the same ‘now’ as the ‘now’ in other regions of the universe. Independently of where we are, the ‘now’ is the same. If this is true, simultaneity is absolute. Both presentism and the growing block view assume the absoluteness of simultaneity. There is a knife-edge present moment stretched throughout the entire universe. That universal now is the boundary of all that exists. According to presentism, what was before that moment and what lies ahead that moment does not exist. According to no-futurism, what lies ahead that moment does not exist.

This common-sensical picture is in tension with the special theory of relativity. This theory is included in two central pillars of contemporary physics: the general theory of relativity and the quantum field theory. Whether we are dealing with gravitational effects or high-energy physics, time dilation is prevalent. This result is of central importance to eternalism, as the relativity of simultaneity is included in time dilation. Simultaneity differs across frames of reference. Provided that in some frame of reference the time difference between two events is zero, the events are simultaneous. In another frame, the time-difference between those same events is not zero, so the events are successive. They might be successive in a different order in a third frame.

The classical argument for eternalism hinges on this result. Before delving into this argument more explicitly in Section 2, let’s consider some intuitions that arise from relative simultaneity. Imagine three observers witnessing two events in a room with one door and a window. The first observer stands still and sees the window and the door open simultaneously. In their frame, the two events are simultaneous, that is, happening now. The second observer moves toward the window and away from the door. For them, the window opens now, and the opening of the door is in their future. The third observer moves toward the door and away from the window. For them, the door opens now, and the opening of the window is in their future. Thus, the three observers disagree on what happens now. Someone’s ‘now’ can be someone else’s future, and it can also be that someone’s ‘now’ is someone else’s past.

Another way to motivate eternalism is to imagine, for the sake of the argument, that there is an alien standing still in a faraway galaxy, around ten light-years from us. I am now practically motionless as I am typing these sentences. Let’s imagine we could draw a now-slice that marks the simultaneity of the alien standing and me sitting. Provided we do not move, we share the same moment ‘now’. Then the alien starts to move, not too fast, away from me. The alien’s now-slice is now tilted toward my past. With a great enough distance between us, even what could be considered a relatively slow motion, the alien would carve up spacetime so their now-slice would no longer match with mine. It would match with Napoleon’s invasion of the Russian Empire. If the alien turns in the opposite direction, their now-slice would be tilted toward my future. Their ‘now’ would be—well, that we do not know. Perhaps a war with sentient robots on Earth?

According to the general theory of relativity, gravitational time dilation causes time in one location to differ from time in another. Clocks closer to massive sources of gravity tick slower than those farther away. This phenomenon is evident even in simple scenarios, such as two clocks in a room – one high on the wall and the other lower on a table – showing different times. According to presentism, there are no different times. There is one and only one time, the present time. However, the potential number of clocks is indefinite, leading to countless different times. This is clearly in tension with presentism. There are many different times, not just one unique time.

At first sight, eternalism is backed up by empirical science. We are not dealing with a purely a priori argument. Time dilation is apparent in a plethora of experiments and applications that utilize relativity. These include, for example, the functioning of CERN’s Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland, the detection of muons at the ground of the earth, and GPS technology. The important point for motivating eternalism is that the empirical evidence for the existence of time dilation in nature is very extensive and well-corroborated. Metaphysicians with a naturalist bent have reasons to take the ramifications of relativity seriously.

b. Central Definitions and Positions

The different metaphysics of time can be clarified by introducing reality values. The assumption is that an event has either a reality value of 1 (to exist) or 0 (to not exist). An event does not hover between existing and non-existing (it is however possible to connect the truth values of future-tensed statements to probabilities as the future might be open and non-existent; more about this in Section 4.d).

|

Eternalism |

|||

| Temporal location | Past | Present | Future |

| Reality value | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Presentism | |||

| Temporal location | Past | Present | Future |

| Reality value | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Growing block, possibilism, no-futurism | |||

| Temporal location | Past | Present | Future |

| Reality value | 1 | 1 | 0 |

As the moving spotlight view differs in terms of actuality, it is appropriate to add an actuality value on its own row:

| Moving spotlight | |||

| Temporal location | Past | Present | Future |

| Reality value | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Actuality value | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Presentism, growing block view, and moving spotlight view all treat tenses as absolutes, whereas eternalism treats them as indexicals. The former take that the distinction between past, present, and future is absolute, whereas the latter takes that it is perspectival. The former are instances of the A-theory of time, whereas the latter is a B-theory or a C-theory of time, as shall be clarified in Section 3.a. This article focuses on eternalism, so not too much will be said about the other metaphysics of time. To that end, see Section 14.a “Presentism, the Growing-Past, Eternalism, and the Block-Universe” of this Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy on Time, as well as the section on A-theory and B-theory.

2. The Classical Argument for Eternalism

a. History of the Concept

It is far from clear who was the first one to use the concept of “eternalism”. It is not even clear where to look for in the first place. Frege’s late 19th-century theory of propositions has been interpreted in eternalist terms, as propositions have an eternal character (O’Sullivan 2023). Hinton published an essay “What is the Fourth Dimension?” in the 1880s. This was perhaps a precursor to eternalism, as the idea of the fourth dimension is co-extensive with the idea of the four-dimensional spacetime. It has been suggested that Spinoza in the 17th century (Waller 2012) and Anselm around 1100 argued for an eternalist ontology (Rogers 2007). Spinoza held that all temporal parts of bodies exist, thus anticipating a perdurantist account of persistence, a view that aligns well with the existence of all times. Anselm thought that God is a timeless, eternal being (a view also held by his predecessors like Augustine and Boethius) and that all times and places are under his immediate perception. Past, present, and future are not absolute distinctions but relative to a temporal perceiver. The history of the philosophy of time certainly stretches farther in time and place. It might very well be that eternalism, or a position close to it, was conceptualized by the ancient philosophers in the West and the East.

Considering the contemporary notion of eternalism and the debates within current metaphysics of time, the special theory of relativity includes the essential ingredients for eternalism. Although the theory has forerunners, it is typically thought to originate in Einstein’s 1905 article “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” and in Minkowski’s 1908 Cologne lecture “Space and Time.” We can assume that the earliest relevant publications concerning eternalism that draw on relativity came out in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

The classical argument for eternalism was formulated in the 1960s by Rietdijk and Putnam, independently of each other, but neither used the notion of eternalism explicitly. In the 1980s, Maxwell and Penrose argued along the lines of Rietdijk and Putnam without using the notion of eternalism. Rietdijk’s or Putnam’s predecessors like Williams (1951) and Smart (1949) did not invoke eternalism explicitly. Surprisingly, not even Russell, who is known for his tenseless theory of time, mentions eternalism in his 1925 exposition of relativity, The ABC of Relativity. The last chapter of that book is “Philosophical consequences,” in which one would expect something to be said about the ontology of time.

It is also worth mentioning one famous quote of Einstein, drawn from a letter to the widow of his long-time friend Michele Besso. This was written shortly after Besso’s demise (he died on March 15, 1955, and Einstein’s letter is dated on March 21, 1955). The letter reads, “Now he has departed from this strange world a little ahead of me. That signifies nothing. For those of us who believe in physics, the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” (Mar 2017: 469). It is not difficult to find Internet forums in which this part of the letter is characterized as eternalist. To dub this eternalism is, however, to read a personal, poetic letter out of its context. Moreover, the letter is cryptic. It is by no means an explicit endorsement of a philosophical position, as one would expect from a personal, moving letter.

There are quite a few 20th-century philosophers, physicists, and mathematicians, like Cassirer, Eddington, Einstein, Grünbaum, Gödel, Lewis, Minkowski, Quine, Smart, and Weyl, who have endorsed a view akin to eternalism (Thyssen 2023, 3). Yet the central argument and motivation for contemporary eternalism comes from the Rietdijk-Putnam-Maxwell-Penrose argument, which will be denoted the ‘classical argument’ below. The most recent extensive defense of this same idea comes from Peterson and Silberstein (2010).

b. The Argument

The two important notions required for the eternalist argument are reality value and reality relation. Reality values, or better for logic notation, r-values, represent the ontological status of any event. 1 denotes a real event, 0 an unreal event. An ideal spacetime diagram that represents everything from the beginning to the end would record all events with a reality value of 1, but none with a reality value of 0. This starting point omits some higher values like “possibly real” or “potentially real in the future,” which will become relevant in the discussion about the openness of the future in quantum physics (Section 4.d). The uniqueness criterion of reality means that an event has only one reality value. An event having two different reality values, 1 and 0, would be a contradiction. Reality relations, for their part, apply to events that share the same reality value. They can be translated into equally real relations: when two events are equally real, they are in a reality relation with each other (Peterson and Silberstein 2012, 212).

If events A, B, and C are equally real, then ArBrC. The properties of the reality relation are reflexivity, symmetricity, and transitivity. Reflexivity stipulates that ArA, since A has a unique reality value. Symmetricity stipulates that if ArB then BrA, since A and B have the same reality value. Transitivity stipulates that if ArB and if BrC, then ArC, since A, B, and C all have the same reality value. The transitivity condition is the most controversial (see Section 4.a).

As noted already in the introduction, the relativity of simultaneity is of the utmost importance for eternalism. So is the idea of four-dimensional spacetime, and concepts related to spacetime diagrams, something originally introduced by Minkowski in 1908.

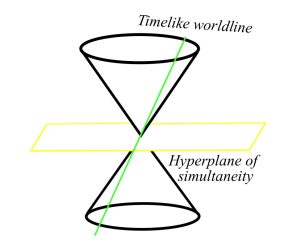

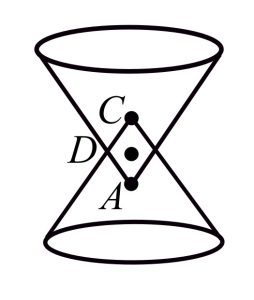

Figure 1. Minkowski light cones

Only events lying outside light cones, that is, spacelike separated events that are in each other’s absolute elsewhere, may be simultaneous. These events are not causally related, and no signals may traverse between them. If one can establish that two spatially separated events are connected with a hyperplane of simultaneity, they are simultaneous. Hyperplanes do not apply to lightlike (the edges of the cones) or timelike (the observer’s worldline) separated events. Events in the observer’s past or future light cones cannot be simultaneous. Different observers do not agree on the temporal order of spacelike separated events. Two or more events happen at the same time in different places, according to some observers, but not according to all.

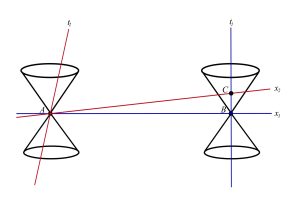

Figure 2. The classical argument illustrated with spacetime diagrams.

In Figure 2, we have three events, A, B, and C. There are two observers, that is, inertial frames of reference. 1 is marked with a blue axis, and 2 is marked with a red axis. A and B are spacelike separated from each other, as are A and C. B and C are timelike separated in relation to each other. Provided that one may establish a hyperplane of simultaneity among spacelike separated events, A is simultaneous with B in observer 1’s frame, and A is simultaneous with C in observer 2’s frame. To use the notion s to denote simultaneity, we may write: AsB for 1, and AsC for 2.

The classical argument assumes that events have unique r-values. Physical events exist independently of observers, they are located somewhere in spacetime. Whether a coordinate system is designated matters not to the existence of the event. Moreover, when dealing with separate, distinct events, these do not affect each other in any way. We may assume that distant events are equally real. If this assumption is correct, then simultaneous events are equally real. AsB should align with ArB, and AsC with ArC.

To spell out the eternalist argument:

Premise 1 AsB

Premise 2 AsC

Premise 3 AsB → ArB

Premise 4 AsC → ArC

Premise 5 ArB ∧ ArC

Conclusion ArB ∧ ArC → BrC

The presentist or growing blocker cannot accept the above conclusion, only two of the premises:

Premise 1 AsB

Premise 2 AsB → ArB

Premise 3 ¬BsC → ¬BrC

Conclusion ArB ∧ ¬BrC

The presentist and growing blocker both agree that the present is completely universal. In any place of the universe, what occurs in a moment is the exact same moment as in any other place. Every existing thing is simultaneous with any other existent thing. Everything that exists exists now. The now becomes redundant with such claims, as “happens now” means simply “happens”, as happening outside of the present has no reality value. All events are simultaneous. If B occurs now, C cannot occur, as it does not yet exist. From the eternalist viewpoint, B and C are equally real. If the classical argument for eternalism that draws on the relativity of simultaneity is valid, then presentism and the growing block view are committed to BrC ∧ ¬BrC. That would render these doctrines contradictory and absurd.

Penrose (1989) presents a similar eternalist argument (well-illustrated here). Imagine two observers, Bob and Alice. They pass each other at normal human walking speeds. Alice walks toward the Andromeda galaxy, Bob in the opposite direction. Andromeda is about 2×1019 kilometers from Earth. Stipulating that the Earth and Andromeda are at rest with respect to each other (which they are actually not, as is also the case in the Alien example discussed previously in Section 1.a), Alice’s and Bob’s planes of simultaneity intersect with Andromeda’s worldline for about five days. Imagine then that an Andromedan civilization initiates war against Earth. They decide to attack us in a time that sits between Alice’s and Bob’s planes of simultaneity. This means that the launch is in Alice’s past and in Bob’s future. The space fleet launching the attack is an unavoidable event. An event can be in some observer’s past (Alice), in some observer’s future (Bob), and in some observers’ present (at Andromedan’s home, at the time they take off, this event occurs now for them).

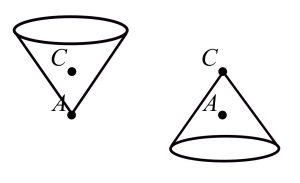

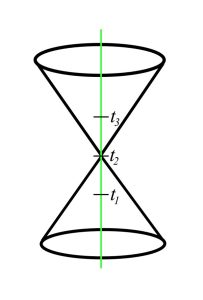

So far, we have focused on the reality values of events. The Minkowski coordinate system enables us to assess tenses: the present in the origin, and the past and the future in the light cones. How one argues for the direction of time is a huge topic of its own; it will not be dealt with here. Here it is assumed that future light cones point toward later times and past light cones toward earlier times. We may stick with the same events, A and C, as in the previous Figure 2. Let’s say there is some observer at event A. For them, event A occurs now, and event C is in their future. Another observer at event C: the event C occurs now for them, while A is in their past.

Figure 3. On the left: Future event C for an observer at A when A occurs now for them. On the right: Past event A for an observer at C when C occurs now for them.

Let’s say there is yet another event that we just previously did not mention: D. This event occurs now for an observer located at D. A is in their past, and C in their future.

Figure 4. For an observer at D, D occurs now,

Figure 4. For an observer at D, D occurs now,

A is in the past, and C in the future.

This brings us to the semantic argument for eternalism initiated by Putnam. He contrasts his position to Aristotle on future contingents. Putnam sees Aristotle as an indeterminist. Statements about potential future events do not have truth values in the present time. Putnam maintains Aristotle’s theory is obsolete, as it does not fit with relativity. The semantic argument can be clarified with the aid of Figure 4 above. When an observer at A utters a statement, “Event D will occur,” and an observer at C utters a statement, “Event D did occur,” one would expect both statements to have definite truth-values. Claims about future or past events are either true or false. Provided a physical event exists in some spacetime location, it does not matter in which spacetime location the observer who utters the existence claim is located. The occurrence of some physical events is not a subjective matter. From the four-dimensional perspective, D’s occurrence has a definite truth-value grounded in its definite reality value.

Putnam’s argument can be bolstered by truthmaker semantics. For something to be true about the world, there has to be something on the side of the world, perhaps a fact, state of affair, being, or process, that makes the statement, assertion, proposition, or theory about that aspect of the world true. In the case of physical events like D, that event itself would be the truthmaker for an existence claim like “Event D occurs at a given location in spacetime.” The truthmaker does not depend on the contingent spacetime location in which the existence claim is uttered. Even if past, present, and future are frame-relative, the physical event itself is not. Unlike tensed predicates (past, present, future), truthmakers (like an event) are not indexical. Armstrong (2004, chapter 11), for one, supports eternalism, or omnitemporalism, as he calls it, based on a truthmaker theory. Eternalism does not face some of the difficulties that presentism has about truthmaking, including postulating truthmakers in the present, finding them outside of time, or accepting non-existents as truthmakers.

3. Eternalism in Relation to Other Metaphysical Issues

a. Dynamic A-theory and Static B-theory

An exposition of the A-theory and the B-theory is provided in this Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy article. In short, A-theorists think time is structured into past, present, and future. B-theorists think time is structured according to earlier than, simultaneous with, and later than relations. There is also the C-theory of time, which maintains that time is structured according to temporal in-betweenness relations. The A-theory is typically called dynamic; the B/C-theory is static. Presentists, growing blockers and moving spotlighters are A-theorists. Eternalists are typically, but not always, B-theorists. A-theorists maintain that time passes, while B/C-theorists deny the passage of time.

Mellor (1998) is a B-theorist who denies that events could be absolutely past, present, or future. Under his theory, properties like being past, being present, and being future do not exist. When statements about pastness, presentness, or futureness of events are made, they can be reformulated in a way that uses the resources of the B-theory. An event that happened in the past means that e is earlier than t. An event happening now means that e is located at t. An event that will happen means that e is later than t. Tensed sentences are switched into tenseless sentences.

Eternalism and the B-theory are typically categorized as the static theory of time. In this view, there is no passage of time in the sense that the future approaches, turns into the present, and then drifts off into the past. The four-dimensional world is thought to be changeless. This is based on the following issue (Price 1996, 13). We are misled by imagining the universe as a three-dimensional static spatial block, with time treated as an external dimension. However, in the framework of four-dimensional spacetime, time is not extrinsic but intrinsic. Time is one dimension of spacetime. Each clock measures proper time, the segment of the clock’s own trajectory in spacetime. Along the observer’s timelike worldline, events are organized successively, perhaps according to earlier than and later than relations. Above this temporal order there is no temporal passage.

The proponents of eternalism typically do not admit temporal flux, an objective change in A-properties, to be part of reality. Grünbaum (1973) criticized vehemently the idea of passage of time. In his view, relativity does not permit postulating a transient now. The now denoting present time is an arbitrary zero, the origin of temporal coordinates at the tip of Minkowski light cones. Absolute future and absolute past are events that take place earlier than or later than the arbitrarily chosen origin, the present moment. Relativity allows events to exist and sustain earlier than t or later than t relations, not any kind of objective becoming. In his view, organisms are conscious of some events in spacetime. Organisms receive novel information about events; there is no coming into existence and then fading away.

b. Passage of Time

A great many philosophers (not only philosophers of physics like Grünbaum) are and have been against the idea of passage of time. Traditionally, logical a priori arguments have been laid against passage. These can be found from very early philosophical sources, like Parmenides’ fragments. There is an inconsistency involved in thinking about passage. If the future, which is nothing, becomes the now, which is something, then this existing now becomes the past, which is nothing. How can nothing become something and something become nothing? How can non-existing turn into existing, and existing disappear into non-existing?

At first sight, eternalism is inconsistent with passage. If all times, past, present, and future exist, then the future does not come to us, switch into the ‘now’, and then disappear into the past. No thing comes into existence; no thing comes out of existence. All entities simply be, tenselessly. How does eternalism deal with the passage of time? There are different strategies for answering this question. 1) Passage is an illusion. We might experience a passage, but this experience is mistaken. 2) We believe that we experience passage, but we are mistaken by that belief. 3) Although the orthodox relativistic eternalism points towards B-theory and perspectivity and indexicality of tense, the moving spotlighters disagree. They maintain that the passage is a genuine feature of reality. 4) There is a passage of time, but that passage is something different than change along the past–present–future. Deflationary theories treat passage as a succession of events. The two first options are anti-realist about passage, while the last two are realistic.

i. The Illusion Argument

According to Parmenides, reality lacks time and change in general. Parmenidian monism suggests that the one and only world, our world, is timeless. Our experience of things changing in time is an illusion. All-encompassing antirealism about time is not currently popular. Yet the classic article for contemporary debates, McTaggart’s “The Unreality of Time” from 1908, is antirealist. Somewhat like Parmenides, McTaggart maintained that describing the world with tensed concepts is illogical. Past, present, and future are incompatible notions. An event should be either past, present, or future. It would be contradictory to claim that they share more than one tensed location in time. But that is how it should be if time passes. Perhaps the distinction introduced by the A-series “is simply a constant illusion of our minds,” surmises McTaggart (1908, 458).

In addition to aprioristic reasoning, there are empirical cases to be made for the illusion argument. There are various motion illusions. The color phi phenomenon might be taken to lend support to the argument that passage of time is an illusion. In the case of color phi, we wrongly see a persistent colored blob moving back and forth. It appears to change its color. Our experience is not veridical. There is no one blob changing its color, but two blobs of different colors. There is no reciprocating motion to begin with. We somehow construct the dynamic scenario in our experience. Perhaps we also create the animation of the flow of time from the myriad of sensory inputs. Another motion illusion: Say someone spins rapidly multiple times. After they stop spinning, the environment seems to move around them. It does not; that is the illusion. This is caused by the inner ear’s fluid rotation. It could be that the flux of time is a similar kind of phenomenon.

ii. Error Theory

Temporal error theory is the following claim: Our belief in the experience of time passing from the future to the present and to the past is false. Temporal error theory can be challenged by considering the origin of our temporal beliefs. Where does our belief in the passage of time come from, if not from a genuine experience of passage, of a very real feeling of time passing by? Torrengo (2017, 175) puts it as follows: “It is part of the common-sense narrative about reality and our experience of it not only that time passes, but that we believe so because we feel that time passes.”

One common metaphor is the flowing river. It is not difficult to find inspirational quotes and bits of prose in which time is compared to the flowing of water (although it is difficult to authenticate such sources!):

“Time flows away like the water in the river.” – Confucius

“Everything flows and nothing abides; everything gives way and nothing stays fixed.” – Heraclitus

“Time is like a river made up of the events which happen, and a violent stream; for as soon as a thing has been seen, it is carried away, and another comes in its place, and this will be carried away too.” – Marcus Aurelius

“River is time in water; as it came, still so it flows, yet never is the same.” – Barten Holyday

“Time is a river without banks.” – Marc Chagall

“I wanted to change my fate, to force it down another road. I wanted to stand in the river of time and make it flow in a different direction, if just for a little while.” – April Genevieve Tucholke

Perhaps we assume metaphors of a flowing river from fiction and from our ways of using language more generally. Miller, Holcombe, and Latham (2020) speculate that all languages are at least to some degree passage-friendly. That is how we come to mis-describe our phenomenology of time. This approach does not imply that we tacitly conceptualize the world as containing passage, and then come to describe our experience as including time’s passing. Instead, ”we only come to tacitly conceptualize the world as containing passage—and hence to believe that it does—once we come to deploy passage-laden language,” Miller, Holcombe, and Latham (2020, 758) write. By this conceptualization, we not only believe time to be passing, but we also describe our temporal phenomenology in terms of time’s passing. From error theoretic point of view, this means that we mis-describe our temporal experience.

Note that the error theory should be separated from the illusionist thesis. In the case of illusions, we humans erroneously observe something to be what it is not. There are, for example, well-known optical illusions. Take the finger sausage illusion. Put two index fingers close to your eyes, and you see an individual “sausage” floating in the middle. There is no sausage floating in the air. The illusion is that you really see the floating sausage. We know the mechanism that is productive of the finger sausage illusion, how the gaze direction of the eyes is merged, and the brain corrects this by suppressing one end of the finger. According to the error theory, passage of time is not an illusion because we do not experience time flowing in the first place. We rather falsely believe and describe our temporal phenomenology by using passage-friendly and passage-laden language.

iii. Moving Spotlight

Broad originally expressed (1923, 59) the idea of a moving spotlight: “We imagine the characteristic of presentness as moving, somewhat like the spot of light from a policeman’s bull’s-eye traversing the fronts of the houses in a street.” The illuminated part is the present moment, what was just illuminated is the past, and what so far has not been illuminated is the future. Broad remained critical of this kind of theory. He thought originally in eternalist terms, but his metaphysics of time changed to resemble the growing block view of temporal existence (Thomas 2019).

The moving spotlight theory is a form of eternalism. The past, the present, and the future all exist, yet there is objective becoming. Only one time is absolutely present. That present “glows with a special metaphysical status” (Skow 2009, 666). Cameron (2015, 2) maintains both privileged present and temporary presentness. The former is a thesis according to which there is a unique and privileged present time. The latter is a thesis according to which this objectively special time changes. In other words, for the moving spotlighter, temporal passage is a fundamental feature of reality. The moving spotlight view therefore connects the A-theory with eternalism.

iv. Deflationary Passage

The deflationary theory agrees with traditional anti-realism about passage. There is no unique global passage and direction of time across the entire universe. There is no A-theoretic, tensed passage. There are however local passages of time along observers’ timelike worldlines. Fazekas argues that special relativity supports the idea of “multiple invariant temporal orderings,” that is, multiple B-series of timelike related events. She calls this “the multiple B-series view.” Timelike related events are the only events that genuinely occur successively. “So,” in the view of Fazekas (2016, 216), “time passes in each of the multiple B-series, but there is no passage of time spanning across all events.”

Slavov (2022) argues that the passage of time is a relational, not substantial, feature of reality (see the debate between substantivalism and relationism). Over and above the succession of events, there is no time that independently flows. This should fit with the four-dimensional block view. It, Slavov (2022, 119) argues,

contains dynamicity. Time path belongs to spacetime. The succession of events along observers’ timelike worldlines is objectively, although not uniquely, ordered. One thing comes after another. The totality of what exists remains the same, but there is change between local parts of spacetime regions between an earlier and a later time.

Passage requires that temporally ordered events exist and that there is change from an earlier time to a later time. This is how Mozersky describes his deflationist view in an interview: “such a minimal account captures everything we need the concept of temporal passage to capture: growth, decay, aging, evolution, motion, and so forth.” Growing, decaying, aging, evolving, and moving are all related to change.

c. Persistence and Dimensions of the World

How do things survive change across time? At later times, an object is, however slightly, different from what it used to be at an earlier time. Yet that object is the same object. How is this possible? There are two major views about persistence: endurantism and perdurantism (for a much more detailed and nuanced analysis of persistence, see this article). The former maintains that objects are wholly present at each time of their existence. The objects have spatial parts, but they are not divisible temporally. The eternalists typically side with the latter. Perdurantism is the view that objects are made of spatial and temporal parts, or more specifically, spatiotemporal parts. Most humans are composed of legs, belly, and head in the same way as most humans are composed of childhood, middle-age, and eld. Ordinary objects are so-called spacetime worms; they stretch out through time like earthworms stretch out through space (Hawley 2020).

Endurantism is a three-dimensional theory. An object endures in three-dimensional space. It just sits there, occupying a place in three-dimensional Cartesian space. Time is completely external and independent of the enduring object. Endurantism assumes that the three spatial dimensions are categorically different from the temporal dimension. Perdurantism, for its part, is a four-dimensional theory of persistence. Space and time cannot be completely separated. Bodies do not endure in time-independent space. Rather, objects are composed of spatiotemporal parts. Earlier and later parts exist, as they are parts of the same object. The perdurantist view aligns with eternalism and relativity (Hales and Johnson 2003; Balashov 2010).

Figure 5. Temporal parts of an object in spacetime.

The perdurantist explains change in terms of the qualitative difference among different parts. Change occurs in case an object has incompatible properties at different times. How are the temporal parts connected? What makes, for instance, a person the same person at different times? Lewis (1976a) mentions mental continuity and connectedness. The mental states of a person should have future successors. There should be a succession of continuing mental states. There is a bond of similarity and causal dependence between earlier and later states of the person.

Perdurantism fits nicely with eternalism. It predicates the existence of all temporal parts and times, and it is consistent with the universe having four dimensions. Considering humans, every event in our lives, from our births to our deaths, is real.

d. Free Will and Agency

In his article “A Rigorous Proof of Determinism Derived from the Special Theory of Relativity,” Rietdijk (1966) argues that special relativity theory indicates fatalism and negates the existence of free will. Consider Figure 2. An observer at event B should be able to influence their future. So, they should be able to influence how C will unfold. However, for another observer at event A, event C is simultaneous with A, suggesting that event C is fixed and unalterable. Yet, C lies in the absolute future of the observer at B. C is predetermined. It is an inevitable event, akin to the Andromedan space fleet in Penrose’s example. This notion poses a threat to at least some conception of free will. If the future must be open and indeterminate for agents to choose between alternative possibilities, a relativistic block universe does not allow for such openness.

There are reasons to think that eternalism does not contradict free will. Let’s assume that the future is fixed. It exists one way only. Statements about future events are true or false. Suppose, Miller explains,

It is true that there will be a war with sentient robots. In a sense, we cannot do anything about that; whatever we in fact do, the war with the robots will come to pass. But that does not mean that what you or I choose to do makes no difference to the way the world turns out or that somehow our choices are constrained in a deleterious manner. It is consistent with it being the case that there will be a war with sentient robots, that the reason there is such a war is because of what you and I do now. Indeed, one would expect that the reason there is such a war is in part because we build such robots. We make certain choices, and these choices have a causal impact on the way the world is. These choices, in effect, bring it about that there is a war with the robots in the future. Moreover, it is consistent with the fact that there will be such a war, that had we all made different choices, there would have been no war, and the facts about the future would have been different. The future would equally have been fixed, but the fixed facts would have been other than they are. From the fact that whatever choices we in fact make, these lead to a war with the robots, it does not follow that had we made different choices, there would nevertheless have been a war with the robots (Miller 2013, 357–8).

The future condition of later local regions of the universe depends on the state of their earlier local regions. We, as human agents, have some degree of influence over how things will unfold. For instance, as I compose this article in the 2020s, our actions regarding climate will partly shape the climate conditions in the 2050s. We are not omnipotent, and our understanding of consequences, especially those far into the future, is somewhat uncertain. However, even if it is a fact that the future exists in only one definite way, this does not inherently exclude free will or the causal relationship between actions and their consequences. Subscribing to eternalism does not resolve the debate over free will; one can be a fatalist or affirm the reality of free will within an eternalist framework.

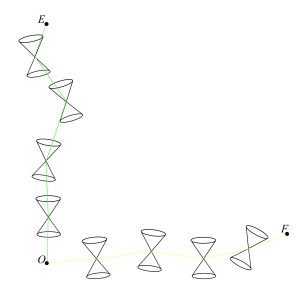

One weakness to note about Rietdijk and Penrose’s arguments, at least if they are used to deny freedom of the will, is their focus on spacelike separated events. These events exist beyond any conceivable causal influence. It is obvious that if a distant civilization, with which we have no communication or interaction, decides to attack us, we cannot influence that decision. Events occurring in regions of the universe beyond our reach remain indifferent to our capacity to make free choices. What truly pertains to freedom of choice are events lying within the future light cone of the observer, not those outside or within the past light cone. Norton provides an illustrative example with mini spacetimes:

Figure 6. Causal connectibility.

Drawing based on Norton (2015, 211).

An observer at the origin of their path in O may only influence events that will be in the multiplicity of the future light cones, along the line towards event E, as they are timelike separated from them. There is no way to affect anything toward the spatially separated event F. Only future timelike or lightlike separated events can be affected, as in that case the affection stays within the cosmic speed limit, the speed of the electromagnetic spectrum frequency. Action from O to S would require the observer to surpass the maximum speed limit.

An important asymmetry within the eternalist framework is between perception and action. We may never perceive the future or affect the past. When perceiving something, we always perceive the past. An event, distant from the observer, occurs, and then there is a time-lag during which the information gets transmitted to and processed by the observer. The event causing the perception occurs before its perception. Actions, for their part, are always directed toward the future. All of this can be translated into B-language (Mellor 1998, 105). We may affect what happens before a time t but not what happens after a time t. We may not perceive what happens before a time t but what happens after a time t. This characterization might be misleading. To clarify, imagine time t as the time when we have lunch. Our breakfast occurs before t, and our dinner happens after t. At breakfast, we can influence what we are going to have for lunch, but we cannot observe it yet. At dinner, we can observe what we had for lunch, but we can no longer influence it.

Traditionally, philosophies of time akin to eternalism employ an all-knowing being that can see all times. Around a thousand years ago, Anselm argued that God is timeless, and so the entire world is immediately present to Him. This indicates every place and every time is under his immediate perception. All times from the beginning to the end are real. This is a tenseless view of time, which treats past, present, and future as perspectives relative to a temporal perceiver (Rogers 2007, 3). A more modern, science fiction example could be a being who can intuit the four-dimensional spacetime. That kind of being could somehow see the past, the present, and the future equally. The movie Men in Black 3 portrays a being like this, an alien named Griffin. He sees a past baseball game and a future attack of the movie’s villain in the same way as the present.

There is, however, a notable difficulty when it comes to observing the future. Perceiving the future would require turning the temporal asymmetry of causation around. It is hard to understand how causation would function in perception if one could observe events occurring later in time. For example, observing something outdoors requires light originating from the Sun to be reflected towards the observer’s eyes. The photons that strike the retina are eventually transduced into electric charges, which then navigate their way through the brain, resulting in the creation of a visual experience. Reversing the temporal direction in this process would be extremely weird. It would imply that the charges in the brain are transformed into light particles, which are then emitted from the eyes towards the object on Earth, subsequently traveling back towards the Sun and initiating physical processes there.

e. The Possibility of Time Travel

At first sight, presentism cannot accommodate time travel because, according to presentism, there are no various times in which one could travel. There is only the present time, but no other times that we could, even in principle, access. Past objects and future objects do not exist, so we cannot go and meet them, just like we cannot meet fictional beings. Not everyone, however, thinks that presentism could not deal with time travel (see Monton 2003).

For its part, eternalism is, in principle, hospitable to the idea of time travel. If the entire universe exists unconditionally, all spacetime with its varying regions simply be. We could travel to different times because all times exist. Traveling to different spatial locations is made possible by the existence of all spatial locations and the path between them. Four-dimensionally, there is a timelike path between different spacetime locations.

Travel to the future is in some sense a trivial idea: we are going toward later times all the time. As writing this encyclopedia article takes x months of my time, it means I am x months farther from my birth and x months closer to my death from starting to finishing writing. Time dilation is consistent with future time travel in another way. An observer traveling close to the speed of light or situated close to a black hole will age more slowly than an observer staying on Earth. After such a space journey, when they get back home to Earth, the traveler would have traveled into the future.

The question about traveling into the past, like to regions of spacetime that precede our own births, is more controversial. If closed timelike curves are possible, then at least in principle time travel to times earlier than our births is possible. This raises interesting questions about what we could do in our pasts. Can we go on and kill our grandparents? Lewis published a famous article in the 1970s, in which he argued that travel to the past is possible, and there is nothing paradoxical about it.

4. Objections

Eternalism has faced numerous strands of criticism. Typical objections concern eternalism’s putative incapability of dealing with change and free will (Ingram 2024). The issue of changelessness was tackled in Section 3.a, and the issue of free will in Section 3.d. Below, five more objections are presented, including possible answers to them.

a. Conventionality of Simultaneity

The conventionality of simultaneity poses a challenge to the classical argument for eternalism (see Ben-Yami 2006; Dieks 2012; Rovelli 2019). The conventionality of simultaneity was something already noted by Poincaré in the late 1800s and by Einstein in the early 1900s. If we are dealing with two spatially separated places, or spacelike separated events, how can we know that these places share the same time and that these events happen at the same time? How do we know that clocks at different places show the same time? How do we know that the ’now’ here is the same ‘now’ in another place? How do we know that the present extends across space even within a designated inertial frame?

Here we have the problem of synchronization. Say we could construct two ideal clocks with the exact same constitution separated by a distance AB. According to Einstein’s proposal, we may send a ray of light from location A to B, which is then reflected from B to A. The time the signal leaves from A is tA, which is measured by an ideal clock at A. The time it gets to B and bounces back is tB, and that time is measured by an identical clock at B. The time of arrival at A is measured by the clock at A. The two clocks are in synchrony if tB – tA = tA’ – tB.

In his Philosophy of Space and Time (1958), Reichenbach went on to argue that simultaneity of two distant events is indeterminate. He adopted Einstein’s notation but added the synchronization parameter ε. The definition of synchrony becomes tB = tA + ε(tA’ – tA), 0 < ε < 1. If the speed of light is isotropic, that is the same velocity in all directions, ε = 1/2. However, because the constant one-way speed of light is a postulate based on a definition, not on any brute fact about nature, the choice of the synchronization parameter is conventional (Jammer 2006: 176–8). Provided that simultaneity is a matter of convention, different choices of the synchronization parameter ε yield different simultaneity relations. If hyperplanes are arbitrary constructions, arguments relying on ontological simultaneity and co-reality relations become questionable. Conventionality implies that spacelike separated events are not even in a definite temporal order. If this is correct, the classical eternalist argument does not even get off the ground.

The conventionality objection relates to the issue of transitivity. Some relations are clearly transitive. They form chains in which transitivity holds. If A is bigger than B and B bigger than C, then A is bigger than C. Yet if A is B’s friend and B is C’s friend, it does not necessarily follow that A is C’s friend. How about simultaneous events being equally real? Do the premises AsB → ArB and AsC → ArC hold in the first place? They should, if we are to truthfully infer that ArB ∧ ArC → BrC. If distant simultaneity is a matter of convention, there seems to be no room for implying that events happening at the same time share the same reality value. Moreover, per Reichenbach’s causal theory of time, only causally connectable events lying in the observer’s light cones are genuinely temporally related. Outside light cones, we are in the regions of superluminal signals. What lies outside light cones is in principle not temporally related; spacelike separated events are neither simultaneous (occurring now) nor past or future. There is no fact of the matter as to which order non-causally connectable events occur. This applies to a great many events in the universe. As the universe is expanding, there are regions that are not causally connected. The different regions have the Big Bang as their common cause, but they are not otherwise affecting each other. They are therefore not temporally related.

Although conventionalism can be laid against eternalism, it can also be taken to support eternalism. Presentism and the growing block view require that the present moment is universal. There should be a unique, completely universal present hyperplane that connects every physical event in the universe. In that case, it should be true that the present time for the observer on Earth is the same time as in any other part of the universe. This means that it also should be true that a time that is past for an observer on Earth is past for an observer at any other place in the universe. Likewise, a future time for an observer on Earth, which both the presentist and no-futurist think does not yet exist, does not exist for any observer anywhere. Presentism and the growing block view both should accept the following to be true: “The moment a nuclear reaction in Betelgeuse occurs, the year 2000 on Earth has either passed or not.” If we consider the relativity of simultaneity, in some frames the year 2000 has passed at the time the reaction occurs but in some other frames it has not. If we consider the conventionality of simultaneity, the statement in question is not factual to begin with. As for the non-eternalist the statement must be true; for the eternalist, it is false (based on relativity of simultaneity) or it is not truth-app (based on conventionality of simultaneity). In both cases, the statement in question is not true, as the passing of the year 2000 and the reaction occurring have no unique simultaneity relation.

b. Neo-Lorentzianism

Historically, Lorentz provided an ether-based account of special relativity. His theory retains absolute simultaneity and is, in some circumstances, empirically equivalent to Einstein-Minkowski four-dimensional theory. Lorentz’s theory is not part of currently established science. It was abandoned quite a long time ago, as it did not fit with emerging general relativity and quantum physics (Acuña 2014).

There has however been an emerging interest in so-called Neo-Lorentzianism about relativity in the 2000s. Craig (2001) and Zimmerman (2007) have both argued, although not exactly in similar ways, for the existence of absolute simultaneity. This interpretation of special relativity would, against the orthodox interpretation, back up presentism. Craig’s theological presentism leans on the existence of God. “For God in the “now” of metaphysical time,” Craig explains (2001, 173), would “know which events in the universe are now being created by Him and are therefore absolutely simultaneous with each other and with His “now.”” According to this interpretation, there is a privileged frame of reference, the God’s frame of reference. Zimmerman does not explicitly invoke Neo-Lorentzianism. In his view, there is nevertheless a privileged way to carve up spacetime into a present hyperplane:

My commitment to presentism stems from the difficulty I have in believing in the existence of such entities as Bucephalus (Alexander the Great’s horse) and the Peloponnesian War, my first grandchild, and the inauguration of the first female US president. It is past and future objects and events that stick in my craw. The four-dimensional manifold of space-time points, on the other hand, is a theoretical entity posited by a scientific theory; it is something we would not have believed in were it not for its role in this theory, and we should let the theory tell us what it needs to be like. As a presentist, I believe that only one slice of this manifold is filled with events and objects (Zimmerman 2007, 219).

These approaches maintain that the present moment is ontologically privileged, as there is a privileged frame of reference and a privileged foliation of spacetime. These views can be seen as revising science on theological and metaphysical grounds. Some, like Balashov and Jansen (2003), Wüthrich (2010, 2012), and Baron (2018), have criticized these strategies. Here we may also refer to Wilson’s (2020, 17) evidential asymmetry principle. To paint with a broad brush, physical theories are better corroborated than metaphysical theories. Physical theories, like special relativity, are supported by a vast, cross-cultural, and global consensus (not to mention the immense amount of empirical evidence and technology that requires the theory). Making our metaphysics match with science is less controversial than making our science match with intuitively appealing metaphysics. Many intuitions—only the present exists, time passes unidirectionally along past-present-future, a parent cannot be younger than their children—can be challenged based on modern physics.

Alternative interpretations of relativity usually invoke something like the undetermination thesis. There is more than just one theory, or versions of the same theory, that correspond to empirical data. Hence, the empirical data alone does not determine what we should believe in. This motivates the juxtaposition of the Einstein-Minkowski four-dimensional theory and the Lorentz ether theory. Even though there are historical cases of rival theories that at some point in history accounted for the data equally well, this does not mean that the two theories are equal contestants in contemporary science. The two theories might not be empirically equivalent based on current knowledge. Impetus/inertia, phlogiston/oxygen, and Lorentz/Einstein make interesting alternatives from a historical viewpoint. It would be a false balance to portray them as equally valid ways of understanding the natural world. Lorentz’s theory did not fit with the emerging general relativity and quantum field theories. These theories have made a lot of progress throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, and they are parts of established science, unlike the ether theory. Moreover, Einstein’s 1905 theory did not only pave the way for subsequent physics. It also corrected the preceding Maxwellian-Hertzian electrodynamics by showing that electric fields are relative quantities; they do not require an ether in which the energy of the field is contained. Maxwell’s electrodynamics is an important part of classical physics and electric engineering without the assumption of space-permeating ether.

c. General Relativity

Although special relativity, at least its orthodox interpretation, does not lend support to presentism or the growing block view, things might be different in case of general relativity. That theory includes the so-called Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric. This enables one to argue for cosmic simultaneity, the unique hypersurface of cosmic time. This idea requires a fundamental observer that could be construed as one who is stationary relative to the microwave background. In this sense, presentists or growing blockers may argue that although special relativity is at odds with their accounts of the nature of time, this is not so in the case of more advanced science. Swinburne (2008, 244), for one, claims “that there is absolute simultaneity in our homogeneous and isotropic universe of galaxies receding from each other with a metric described by the” FLRW solution. As pointed out by Callender (2017, 75–6) and Read and Qureshi-Hurst (2021), however, we are not fundamental observers, as we are in various relative states of motion. We move on our planet; our planet rotates around its axis; it orbits the Sun; it moves in relation to our galaxy, which in turn moves in relation to other galaxies (for a more astute description, see Pettini 2018, 2). This indicates that we do not have local access to cosmic time.

Black hole physics is also troublesome for presentism and the growing block view. It retains the frame-relativity of simultaneity, so not all observers agree with what is present (see Romero and Pérez 2014, section “Black holes and the present”). Baron and Le Bihan (2023) consider the idea of surface presentism based on general relativity. According to surface presentism, what exists is limited to a three-dimensional hypersurface. Although surface presentism allows there is no preferred frame of reference in physics, it maintains there is a preferred frame in the metaphysical sense. This anchors the one and only actual present moment. Consider the event horizon. Nothing, not even massless particles like photons, can escape from a black hole. The event horizon is the limit between what goes in the black hole and can never leave and the rest of the universe. The later times of the region, what is beyond the event horizon in the black hole, are ones in which nothing that enters it will never escape. What is relevant for the metaphysics of time is the ontological dependence of earlier and later times in black hole physics.

According to the argument of Baron and Le Bihan, there would be no event horizons if surface presentism were true. Surface presentism, as well as presentism in general and the growing block view, maintains there is no future or times later to the present time. Briefly put, the very existence of black holes as evidenced by general relativity is against presentism. As nothing can escape the interior of a black hole after entering it, there is an ontological reference to a later time. No matter how long it takes, nothing can escape. To paraphrase and interpret Curiel (2019, 29), the location of the event horizon in spacetime requires the entire structure of spacetime, from the beginning to the end (and all the way to infinity). All spacetime exists.

d. Quantum Physics

Whereas relativity is a classical, determinist theory and so well-fit with predicating a fixed future, quantum physics is many times interpreted in probabilistic terms. This may imply that the future is nonexistent and open. This would flat-out contradict eternalism. There are good reasons for this conclusion. Take the famous double-slit experiment.

In this experiment, a gun steadily fires electrons or photons individually towards two slits. Behind the slits, a photographic plate registers the hits. Each particle leaves a mark on the plate, one at a time. When these particles are shot one by one, they land individually on the detector screen. However, when a large number of particles are shot, an interference pattern begins to emerge on the screen, indicating wave-like behavior.

At first glance, this is highly peculiar because particles and waves are fundamentally different: particles are located in specific spatial regions, while waves spread out across space.

What is important for debates concerning the nature of time is the probabilistic character of the experimental outcome. Determinist theories, within the margin of error, enable the experimenter to precisely predict the location of the particle in advance of the experiment.

In the double-slit experiment, one cannot even in principle know, before carrying out the experiment, where the individual particle will eventually hit the screen. To put it a bit more precisely, the quantum particle is associated with a probability density. There is a proportionality that connects the wave and the particle nature of matter and light. The probability density is proportional to the square of the amplitude function of the electromagnetic wave. This means we can assign probabilities for detecting the particle at the screen. It is more likely that it will be observed at one location as opposed to another.

This can be taken to imply that the future location of the particle is a matter of open possibility. Before performing the experiment, it is a random tensed fact where the particle will be. Yet eternalism cannot allow such open possibilities, because it treats any event as tenselessly existing. To give a more commonsensical example, eternalism indicates that the winning lottery numbers of the next week’s lottery exist. We were ignorant of those numbers before the lottery because we were not at the spacetime location in which we could see the numbers. Yet the no-futurist, probabilistic interpretation of the situation suggests that the next week’s lottery numbers do not yet exist. The machine will eventually randomly pick out a bunch of numbers.

Putnam’s classical semantic argument for eternalism assumes that statements concerning events have definite truth values, independently of whether they are in the observer’s past or future. This is consistent with a determinist theory, but quantum theory might require future-tense statements that have probabilistic truth values. Hence future events would have probabilistic reality values. Statements concerning what will occur do not have bivalent truth values, but they instead range between 0 and 1 in the open interval [0, 1]. Sudbery (2017) has developed a logic of the future from a quantum perspective. Sudbery (2017, 4451–4452) argues “that the statements any one of us can make, from his or her own perspective in the universe,” when they concern the future, “are to be identified with probabilities.” This account seems to go well with quantum physics and no-futurist views like presentism or the growing block.

One way for the eternalist to answer this objection is to consider a determinist interpretation of quantum mechanics, like the many worlds interpretation, initiated by Everett in 1957. Greaves and Myrvold (2010, 264) encapsulate the underlying Everettian idea: “All outcomes with non-zero amplitude are actualized on different branches.” All quantum measurements correspond to multiple measurement results that genuinely occur in different branches of reality. Under Everettianism, one could think that there is no ‘now’ that is the same everywhere in all of physical reality, but different worlds/branches have their own times. Different worlds within the Everett multiverse or different branches within the single universe are causally isolated. This is not much different from relativistic spacelike separation: different locations in the universe are in each other’s absolute elsewhere, not connected by any privileged hyperplane of simultaneity. There is no unique present moment that cuts through everything that exists and defines all that exists at that instant.

A potential challenge to classical eternalist arguments that draw on the relativity of simultaneity comes from quantum entanglement. Based on the ideas of Bell, Aspect and his team were able in the 1980s to experimentally corroborate a non-local theory. Two particles, separated by distance, turn out instantly to have correlated properties. This could not be the case with only locally defined physical states of the particles. Maudlin (2011, 2) explains that they:

appear to remain “connected” or “in communication” no matter how distantly separated they may become. The outcome of experiments performed on one member of the pair appears to depend not just on that member’s own intrinsic physical state but also on the result of experiments carried out on its twin.

Non-locality might introduce a privileged frame of reference. (For a thorough discussion on non-locality and relativity, see Maudlin (2011).) If this is so, the classical argument that relies on chains of simultaneity relations and their transitivities would perhaps be challenged. A question still remains about time. Gödel (1949) argued that objective passage requires a completely universal hyperplane, a global ‘now’ that constantly recreates itself. It is not clear whether the instant correlation of distant particles in quantum entanglement introduces this kind of unique spacetime foliation required for exclusive global passage of time.

The research programs on quantum gravity aim to weave together relativistic and quantum physics, considering both gravitational and quantum effects. This could potentially yield the most fundamental physical theory. Some approaches to quantum gravity indicate that spacetime is not fundamental. When one reaches the Planck scale, 1.62 x 10-35 meters and 5.40 x 10-44 seconds (Crowther 2016, 14), there might not be space and time as we know them. At first glance, this might challenge eternalism, as the classical argument for it leans on four-dimensional spacetime. Le Bihan (2020) analyzes string theory and loop quantum gravity, arguing that both align with an eternalist metaphysics of time. If deep-down the world is in some sense timeless, the distinct parts of the natural world still exist unconditionally. This undermines presentism and no-futurism, since they rely on positing a global present by means of a unique, universal hyperplane and an absolute distinction between A-properties. Whether something is past, present, or future is not determined by fundamental physics.

e. Triviality

A case has been made that the presentist/eternalist debate lacks substance. Dorato (2006, 51), for one, claims that the whole issue is ill-founded from an ontological viewpoint. Presentism and eternalism reflect our different practical attitudes toward the past, present, and future. Dorato notes that Putnam’s assertion “any future event X is already real” (Putnam 1967, 243) is problematic. This assertion seems to implicitly assume presentism and eternalism. By saying that “the future is already,” we are saying something like “the future is now.” This is contradictory: the present and the future are different times. They cannot exist at the same time.

To be more precise, Dorato (2006, 65) distinguishes between the tensed and tenseless senses of the verb “exist.” In the tensed sense, an event exists in the sense that the event exists now. In the tenseless sense, an event exists in the sense that it existed, exists now, or will exist. These become trivial definitions: both presentists and eternalists accept them. The whole debate is verbal. Presentism maintains that past or future events do not exist now. What happens is that “presentism becomes a triviality” because “both presentists and eternalists must agree that whatever occurs” in the past or future “does not exist now!”. Instead of being an ontological debate, the presentism/eternalism dialogue is a matter of differing existential attitudes toward the past, present, and future.

One way to answer the worry of triviality—and the charge that the whole debate is merely verbal—is to add that presentism and eternalism disagree on what exists unconditionally (the Latin phrase is simpliciter). Consider the following statement S:

S: “Cleopatra exists unconditionally.”

The presentist thinks S is false. All that exists for the presentist are the presently existing entities. When I am composing or you are reading this article, Cleopatra does not exist anymore. The original claim is false, according to the presentist. The eternalist disagrees: S is true for the eternalist while I’m writing and you are reading. We are not in the same spacetime location as Cleopatra, but nevertheless there is a location that the living Cleopatra occupies (Curtis and Robson 2016, 94).

The sense in which presentism and eternalism ontologically agree/disagree can be clarified by specifying the domain of quantification. This clarification borrows from predicate logic. Presentism and eternalism both agree on restricted quantification. It is true, according to presentism and eternalism, that Cleopatra does not exist anymore while writing or reading this article. The two nevertheless respond differently to unrestricted quantification. When quantifying over the totality of what exists, the presentist maintains that the quantification is over the presently existing entities, while the eternalist maintains that the quantification is over the past, the present, and the future entities.

There are many other reasons to think that presentism and eternalism imply separate temporal ontologies. These aspects have already been discussed in this article: dimensionality of the world, indexicality, and persistence. Presentism maintains the existence of a three-dimensional spatial totality plus the universal present moment that cuts through the whole universe. Eternalism denies there is such a universal present moment and that existence is restricted to the present time. Instead, the entire block universe exists (Wüthrich 2010). Eternalism is very different from presentism because it predicates the existence of all events, irrespective of their contingent spacetime location. Presentists cannot accept the existence of all events from the beginning of the universe to its end but limit existence to the presently existing entities, which are thought to be the only existent entities. Presentists may well treat the spatial location ‘here’ as indexical but hold the present to be absolute. Eternalists (apart from the moving spotlight view) treat both spatial and temporal tensed locations as indexicals. Presentists typically assume a perdurantist account of persistence, the view that objects persist the same across time temporally indivisibly, whereas eternalists subscribe to temporal parts in spacetime.

5. References and Further Reading

- Acuña, P. (2014) “On the Empirical Equivalence between Special Relativity and Lorentz’s Ether Theory.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 46: 283-302.

- Armstrong, D. M. (2004) Truth and Truthmakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Balashov, Y. and M. Janssen (2003) ”Presentism and Relativity.” British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 54: 327-46.

- Balashov, Y. (2010) Persistence and Spacetime. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Baron, S. (2018). “Time, Physics, and Philosophy: It’s All Relative.” Philosophy Compass 13: 1-14.

- Baron, S. and B. Le Bihan (2023) “Composing Spacetime.” The Journal of Philosophy.

- Ben-Yami, H. (2006) “Causality and Temporal Order in Special Relativity.” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 57: 459-79.

- Broad, C. D. (1923) Scientific Thought. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Callender, C. (2017) What Makes Time Special? New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cameron, R. (2015) The Moving Spotlight. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Craig, W. L. (2001). Time and the Metaphysics of Relativity. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Crowther, K. (2016) Effective Spacetime. Understanding Emergence in Effective Field Theory and Quantum Gravity. Cham: Springer.

- Curiel, E. (2019) “The Many Definitions of a Black Hole.” Nature Astronomy 3: 27–34.

- Curtis L. and Robson J. (2016) A Critical Introduction to the Metaphysics of Time. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Dieks, D. (2012) “Time, Space, Spacetime.” Metascience 21: 617-9.

- Dorato, M. (2006) “Putnam on Time and Special Relativity: A Long Journey from Ontology to Ethics”. European Journal of Analytic Philosophy 4: 51-70.

- Dowden, B. (2024) “Time.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://iep.utm.edu/time/.

- Einstein, A. (1905/1923) “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies.” In Lorentz et al. (ed.) The Principle of Relativity, 35‒65. Trans. W. Perret and G.B. Jeffery. Dover Publications, Inc.

- Everett, H. I. (1957) “Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics.” Review of Modern Physics 29: 454-62.

- Fazekas, K. (2016) “Special Relativity, Multiple B-Series, and the Passage of Time.” American Philosophical Quarterly 53: 215-29.

- Greaves, H. and W. Myrvold (2010) “Everett and Evidence.” In Saunders, S., Barrett, J., Kent, A. and Wallace, D. (eds.), Many Worlds? Everett, Quantum Theory, & Reality, 264-306. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grünbaum, A. (1973) Philosophical Problems of Space and Time. Second, enlarged version. Dordrecht: Reidel.

- Gödel, K. (1949) “A Remark about the Relationship between Relativity Theory and the Idealistic Philosophy.” In Schilpp, P. A. (ed.), Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, 555-62. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court.

- Hales, S. and Johnson, T. (2003) “Endurantism, Perdurantism and Special Relativity.” Philosophical Quarterly 53: 524–539.

- Hawley, K. (2020) “Temporal Parts.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/temporal-parts/.

- Hinton, C. (1904) The Fourth Dimension. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd.

- Ingram, D. (2024) “Presentism and Eternalism.” In N. Emery (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Time. Routledge.

- Jammer, M. (2006) Concepts of Simultaneity: From Antiquity to Einstein and Beyond. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Maxwell, N. (1985) ”Are Probabilism and Special Relativity Incompatible?” Philosophy of Science 52: 23–43.

- Le Bihan, B. (2020) “String Theory, Loop Quantum Gravity, and Eternalism.” European Journal for Philosophy of Science 10: 1-22.

- Lewis, D. (1976a) “Survival and Identity.” In A. O. Rorty (ed.), The Identities of Persons. Berkeley: University of California Press, 17-40.

- Lewis, D. (1976b) “The Paradoxes of Time Travel.” American Philosophical Quarterly 13: 145-52.

- Mar, G. (2017) “Gödel’s Ontological Dreams.” In Wuppuluri, S. and Ghirardi, G. (eds.), Space, Time, and the Limits of Human Understanding, 461-78. Cham: Springer.

- Maudlin, T. (2011) Quantum Non-locality and Relativity. Third Edition. Wiley-Blackwell

- McTaggart, J. M. E. (1908) “The Unreality of Time.” Mind 17: 457-74.

- Mellor, H. (1998) Real Time II. London and New York: Routledge.

- Miller, K. (2013). “Presentism, Eternalism, and the Growing Block.” In H. Dyke & A. Bardon, eds., A Companion to the Philosophy of Time. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 345-64.

- Miller, K. et al. (2020) “Temporal Phenomenology: Phenomenological Illusion versus Cognitive Error.” Synthese 197: 751-71.

- Minkowski, H. (1923) “Space and Time.” In Lorentz et al. (eds.), The Principle of Relativity, 73-91. Translated by W. Perrett and G. B. Jeffery. Dover Publications.

- Monton, B. (2003) “Presentists Can Believe in Closed Timelike Curves.” Analysis 63: 199-202.

- Norton, J. (2015) “What Can We Learn about the Ontology of Space and Time from the Theory of Relativity.” In L. Sklar (ed.), Physical Theory: Method and Interpretation, Oxford University Press, 185-228.

- O’Sullivan, L. (2023) “Frege and the Logic of Historical Propositions.” Journal of the Philosophy of History 18: 1-26.

- Penrose, R. (1989) The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and Laws of Physics. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peterson, D. and M. D. Silberstein (2010) “Relativity of Simultaneity and Eternalism.” In Petkov (ed.), Space, Time, and Spacetime, 209-37. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Pettini, M. (2018) “Introduction to Cosmology – Lecture 1. Basic concepts.” Online lecture notes: https://people.ast.cam.ac.uk/~pettini/Intro%20Cosmology/Lecture01.pdf

- Price, H. (2011) “The flow of time.” In C. Callender, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Time. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 276-311.

- Putnam, H. (1967) “Time and Physical Geometry.” The Journal of Philosophy 64: 240-7.

- Read, J. and E. Qureshi-Hurst (2021) “Getting Tense about Relativity.” Synthese 198: 8103–8125.

- Reichenbach, H. (1958) The Philosophy of Space and Time. Translated by Maria Reichenbach and John Freund. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.