Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (1775—1854)

F. W. J. von Schelling is one of the great German philosophers of the late 18th and early 19th Century. Some historians and scholars of philosophy have classified him as a German Idealist, along with J. G. Fichte and G. W. F. Hegel. Such classifications obscure rather than illuminate the importance and singularity of Schelling’s place in the history of philosophy. This is because the dominant and most often limited understanding of Idealism as systematic metaphysics of the Subject is applicable more to Hegel’s philosophy than Schelling’s. While initiating the Post-Kantian Idealism of the Subject, Schelling went on to exhibit in his later works the limit and dissolution of such a systemic metaphysics of the Subject. Therefore, the convenient label of Schelling as one German Idealist amongst others ignores the singularity of Schelling’s philosophy and the complex relationship he had with the movement of German Idealism.

F. W. J. von Schelling is one of the great German philosophers of the late 18th and early 19th Century. Some historians and scholars of philosophy have classified him as a German Idealist, along with J. G. Fichte and G. W. F. Hegel. Such classifications obscure rather than illuminate the importance and singularity of Schelling’s place in the history of philosophy. This is because the dominant and most often limited understanding of Idealism as systematic metaphysics of the Subject is applicable more to Hegel’s philosophy than Schelling’s. While initiating the Post-Kantian Idealism of the Subject, Schelling went on to exhibit in his later works the limit and dissolution of such a systemic metaphysics of the Subject. Therefore, the convenient label of Schelling as one German Idealist amongst others ignores the singularity of Schelling’s philosophy and the complex relationship he had with the movement of German Idealism.

The real importance of Schelling’s later works lies in the exposure of the dominant systemic metaphysics of the Subject to its limit rather than in its confirmation. In this way, the later works of Schelling demand from the students and philosophers of German Idealism a re-assessment of the notion of German Idealism itself. In that sense, the importance and influence of Schelling’s philosophy has remained “untimely.” In the wake of Hegelian rational philosophy that was the official philosophy of that time, Schelling’s later works was not influential and fell onto deaf ears. Only in the twentieth century when the question of the legitimacy of the philosophical project of modernity had come to be the concern for philosophers and thinkers, did Schelling’s radical opening of philosophy to “post-metaphysical” thinking receive renewed attention.

This is because it is perceived that the task of philosophical thinking is no longer the foundational act of the systematic metaphysics of the Subject. In the wake of “end of philosophy,” the philosophical task is understood to be the inauguration of new thinking beyond metaphysics. In this context, Schelling has again come into prominence as someone who in the heyday of German Idealism has opened up the possibility of a philosophical thinking beyond the closure of the metaphysics of the Subject. The importance of Schelling for such post-metaphysical thinking is rightly emphasized by Martin Heidegger in his lecture on Schelling of 1936. In this manner Heidegger prepares the possibility of understanding Schelling’s works in an entirely different manner. Heidegger’s reading of Schelling in turn has immensely influenced the Post-Heideggerian French philosophical turn to the question of “the exit from metaphysics”. But this Post-Structuralist and deconstructive reading of Schelling is not the only reception of Schelling. Philosophers like Jürgen Habermas, whose doctorate work was on Schelling, would like to insist on the continuation of the philosophical project of modernity, and yet attempt to view reason beyond the instrumental functionality of reason at the service of domination and coercion. Schelling is seen from this perspective as a “post-metaphysical” thinker who has widened the concept of reason beyond its self-grounding projection. During the last half of the last century, Schelling’s works have tremendously influenced the post-Subject oriented philosophical discourses. During recent times, Schelling scholarship has remarkably increased both in the Anglo-American context and the Continental philosophical context.

Table of Contents

1. Life

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling was born on 27 January, 1775 in Leonberg, Germany. His father was Joseph Friedrich Schelling and mother was Gottliebin Maria Cless. In 1785 Schelling attended the Latin School in Nürtingen. A precocious child, his teachers soon found nothing more to teach him. In 1790, Schelling joined the Tübingenstift, a Protestant Seminary, in Tübingen where he befriended Hölderlin who was later to become a great German poet, and Hegel who was to become a great philosopher. In 1794 Schelling published Über die Möglichkeit einer Form der Philosophie Überhaupt, in the same year of the publication of Fichte’s Wissenshaftlehre. Fichte’s Wissenshaftlehre, along with Kant’s Critique of Judgment that was published four years before (1790), proved to be of decisive importance for Schelling’s early philosophical career. In 1798 at the age of just 23, Schelling was called to a professorship at the University of Jena where he came in contact with German Romantic poets and philosophers like the Schlegel brothers and Novalis. He also met August Wilhelm Schlegel’s wife Caroline Schlegel and there begun one of the most fascinating and scandalous romantic stories of that time, leading to Caroline’s divorce and her marriage to Schelling in 1803. In 1803 he left Jena for Würzburg where he was called to a professorship. In the Autumn of 1805 Würzburg fell to Austria. The following year Schelling left for Munich where he was to stay till 1841 apart from a break between 1820-1827 when he lived in Erlangen. In 1809 Schelling published his great treatise on human freedom, Philosophical Inquiries Concerning the Nature of Human Freedom. A few months later Caroline died.. Schelling was devastated. In 1812 Schelling married Pauline who was to remain his life long companion. In 1831 Hegel died. In 1840 Schelling was called upon to the now vacant chair in Berlin to replace Hegel where he sought to elaborate his Positivphilosophie which was attended by the likes of Søren Kierkegaard, Alexander Humboldt, Bakunin and Engels. In 1854 on 20 August Schelling died at the age of 79 in Bad Ragaz, Switzerland.

2. Philosophy

Encounter with the works of Schelling often baffles the scholars and historians of philosophy. Schelling’s works seem to exhibit the lack of consistent development or systematic completion which most of his contemporaries possess. As a result scholars and historians of philosophy complain of the absence of a “single” Schelling. Recent scholarship, however, while accepting the often disruptive and discontinuous movement with which Schelling’s thinking moves that defies and un-works the completion of a single definite philosophical system, finds issues that are singular to Schelling’s continuous attention and unceasing concern. Thus the absence of a systematic completion is what has become the source of fascination for recent Schelling scholarship. Schelling appears to be the mark that delineates the limit of the systematic task of philosophy, “the end of philosophy and the task of thinking” as Heidegger says. Prominent Schelling scholars like Manfred Frank and Andrew Bowie (1993) have, however, pointed out that Schelling had never abandoned the idea of ‘system’, although the idea of ‘system’ was no longer grounded on a restricted, narcissistic concept of reason as totalizing and self-grounding but as opening to that which cannot be thought in the concept.

For the sake of convenience we can roughly divide the philosophical career of Schelling into four stages:

a. Naturphilosophie and Transcendental Philosophy

b. Identity philosophy

c. The Middle period: Freedom essay and The Ages of the World

d. Positive Philosophy (Philosophy of Mythology and Philosophy of Revelation)

a. Naturphilosophie and Transcendental Philosophy

The significance of Schelling’s early philosophical works lies in its radically new understanding of nature that departs significantly from the then dominant philosophical and scientific understanding of nature. Perhaps the best the way to approach the Schelling of Naturphilosophie is to see him, on the one hand, in relation to the dominant mechanistic determination of nature at that time, that of the Newtonian mathematical determination of nature according to which nature follows certain determinable physical laws of motion and rest, and that can be grasped in the objective cognition that has universal and non-relative validity and on the other hand, as a development of post-Kantian philosophy that led to a radical revision of Kant himself. Schelling’s philosophy of nature thus arose out of the demand to respond to the mechanistic determination of nature that was dominant at that time on the one hand, and to respond to the problems that arose in Kant’s division of the phenomenal realm of nature and noumenal realm of freedom. This demanded a dynamic philosophical account of nature where nature is no longer seen as a totality of objects that are a mere inert, opaque mass, but nature that is subjected to universal laws of causality. Such a dynamic philosophy of nature must be able to resolve the abyss that is opened up in the wake of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. It is the abyss between the deterministic, causal, conditioned realm of understanding on the one hand, and the unconditioned realm of ethical self-determination on the other hand, between theoretical philosophy and practical philosophy. The task that the Post-Kantian philosophy has given to itself is to bridge this gap between the conceptual, constitutive realm of nature which can be grasped by causal laws that has universal validity, and the ethical spontaneity of the practical reason where the ethical subject is beyond the conditioned realm of determination and is thus a free Subject of self-determination. This Subject is the Subject of freedom that cannot be grounded in the constitutive principles of understanding but in the regulative Ideas of reason. J. G Fichte sought to unify the theoretical reason (that is “understanding”) and the practical reason by grounding them both in the dynamic activity of the self-consciousness that posits itself as pure, unconditioned act of self-positing ‘I’. The task of accounting for the process of emergence of the world of nature, which is thus a dynamic process, is addressed by Fichte thus: nature is an essential self-limitation of the ‘I’. The unconditioned, infinite self-positing ‘I’, in order to know itself as itself, divides itself into the finite ‘I’ and its counter-movement “Not-I”. In this manner, Fichte claimed to have resolved the problem that appeared to him and to the post-Kantian philosophers as that which is left unresolved by Kant himself. This is the question of how to account for the mysterious X, “the thing-in-itself” which, according to Kant, can never be grounded in the constitutive principle of understanding. As the condition of possibility of knowledge, “the thing-in-itself” can never be known. It is irreducible to the concepts of understanding. Fichte in his Science of Knowledge accounts for the genesis of this “thing-in-itself” in the pure self-positing act of the ‘I’. Since the ‘I’ cannot be an object of outer sense like any other objects of cognition ( Kant prohibits this), ‘I’ can only emerge in a pure, primordial act of inner-self. This self-emerging ‘I’ cannot therefore be an object of conceptual cognition, of an empirical intuition. It can only be grasped in the inner sense in ‘intellectual intuition’ which is none but ‘the fact of self-consciousness.’ According to Fichte, ‘the thing-in-itself’ is this self-emerging self-consciousness which is a ‘fact’ unlike any other ‘fact’. It is a fact that only ‘intellectual intuition’ grasps in the act of pure self-intuition. This is because only a being capable of intuiting itself as simultaneously representing and represented can account for the unity of representation and object. For such a being, that is ‘I’, there is no other predicate than itself. It is its own object. This object for it appears as nature which is the self-limitation of the self-positing Subject. Fichte’s idealism later came to be known as Subjective Idealism.

Schelling’s early works flourished under the influence of Fichte’s thinking. In 1797 Schelling published an essay called Treatise Explicatory of the Idealism in the “Science of Knowledge” in Philosophisches Journal edited by Immanuel Niethammer. This essay is crucial document for understanding the transition from Kantian critical philosophy to German Idealism. While attempting to elucidate what Kant would have intended if Kant’s philosophy is to prove internally cohesive, Schelling moves to the task of unifying theoretical and practical philosophy in a single principle in such a manner that he actually moves beyond both Kantian and Fichtean philosophy. What allows this unification of theoretical and practical philosophy is the Spirit’s infinite striving to represent the universe. The Spirit is not a static entity given, something mysterious X, but infinite becoming and infinite productivity. It is in this ceaseless production lies the organic nature of human Spirit that is moved by its immanent laws and that has its purposive-ness within itself. Schelling here introduces the notion of organism which unites in its immanence its goal and purpose, its form and matter, concept and intuition. As such each organism is a system which is “an arabesque delineation of the soul” or “eternal archetype” that finds expression in every plant. As immanent unity of form and matter that orients itself towards absolute purposive-ness through successive stages, this organism is not thus mere static, lifeless entity but is said to exhibit life. The Idealist notion of the system here takes this unified world of organism as model. Intuition is the unity of form and matter, representation and object which is distinguishable only in the concept that freely repeats the originary unity. With the help of the schematic power of the imagination, concept here produces the individual object of cognition. The succession of representation occurs alternately in a circle. To move beyond this circle of theoretical knowledge, this circle where the object always returns, it is necessary to introduce an act of free self-determination which cannot be further determined. This act is the absolute act of free will which is primordial and infinite. It is with this act the theoretical and practical philosophy is united.

In the same year Schelling published his Naturphilosophie that further elaborates the concept of organism through analysis of natural phenomena with the help of scientific studies of the day. This work responds to the dual tasks mentioned above. On the one hand it must give an account of a dynamic process of the emergence of nature as against the mechanistic, deterministic understanding of nature; and on the other hand, to resolve the problem left by Kant, that of bridging the realm of theoretical and practical philosophy by developing a dynamic philosophy of nature that takes into account Fichtean dialectical philosophy of consciousness. Like the Treatise of the same year, this new philosophy of nature is not grounded in the self-positing, unconditioned self-consciousness but by positing a “non-objective”, unconditioned in nature itself which Schelling calls “productivity”. It is this productivity that emerges through the logic of polar oppositions between subject and object that is shown to lead to a higher subject-object synthesis. For Schelling such a dialectical logic is deducted as a movement of potencies. The first potency is the movement of infinite to the finite. The second potency makes the reverse movement, while the third potency alone, which is higher than the other two, unities preceding potencies. In this manner Schelling explains magnetism as the first potency, electricity as the second and chemistry as the third potency that dialectically sublates the other two. Schelling’s philosophy of nature that attempts to develop the dynamic process of Idealism from the objective side can be seen as a parallel development to the Subjective Idealism that is elaborated by Fichte.

In the Treatise Explicatory of the Idealism in the “Science of Knowledge” of 1797 Schelling hints at the idea of “the history of self-consciousness”. The Spirit through its originary activity presents the infinite in the finite, a movement whose goal is self-consciousness that marks the unification of theoretical and practical philosophy, nature and history. Schelling perfects this model in his System of Transcendenatl Idealism. Schelling’s publication of The System of Transcendental Idealism in 1800 brought immediate fame to the young 25 year old philosopher. Schelling here draws from Fichte’s great insight that self-consciousness is not a mere “given entity”. It is not an unknown and inaccessible X, a mysterious transcendental “in-itself” as the formal ground of cognition, but a coming into presence of itself, a pure self-positing emergence through the dialectical process of self-positing and self-limitation. In that way a “history of self-consciousness” can be deduced from one principle that explains the coming into being of the theoretical cognition that at its limit passes into the practical realm of freedom, that is, the objective world of history . This is the task of Schelling’s System of Transcendental Idealism of 1800. Thus the axiomatic sense of Fichtean I=I is transformed into the dynamic deduction of the self-consciousness by one principle. This is emergence of the Idealist notion of System whose possibility, according to the Idealists, is already given in Kantian Critical philosophy; a possibility is denied by Kant himself.

“The history of self-consciousness” comes into being in three stages or epochs. While the first epoch manifests the coming into being of “productive intuition” from “original sensation” and the second epoch manifests the emergence of “reflection” from “productive intuition”, the third epoch recounts the emergence of “the absolute act of will” from “reflection”. At the end of the third epoch, “the history of self-consciousness” passes into the practical realm where the deduction of the concept of history is shown to be the realm of unity of freedom and necessity. This has led Schelling to ask at the end of System: how the Subject which is now a completed self-consciousness can become conscious of that moment of its origin which is now unconscious for it, a past that appears to have receded into an immemorial origin and is inaccessible? It now appears that the condition of possibility of consciousness as such remains irreducible to consciousness itself. This is the problem that has become decisive, not only for Schelling’s subsequent philosophical career, but for the fate of Idealism as such. It now appears as if our self-consciousness is driven or constituted by an unconscious ground, forever inaccessible to consciousness, which can never be grounded in consciousness itself.

For Schelling this shows the limit of philosophical cognition and at the same time the importance of works of art. By refusing the claim to say or represent the synthesis of unconscious and conscious, the work of art rather shows it. Therefore art can be said to be the “the eternal organ and document of philosophy” whose basic character is an “unconscious infinity” that arises in the work of art’s synthesis of nature and freedom. While the artist initiates a work of art with a manifest, conscious intention, she, in an unconscious and unintentional manner, depicts infinity without representing or saying it. Such an unintentional showing exceeds the representational acts of consciousness. It cannot be reduced to categorical statements. Therefore works of art cannot be understood on the basis of pre-given set of rules. Works of art are not exhausted in the normative or axiomatic definitions as to ‘what constitutes art as such’. What constitutes the ‘essence’ of art lies rather in its excess of showing over the said. In that sense works of art are more analogous with organisms by virtue of its existing as a link between unconsciousness and consciousness. Such a link can only be shown and therefore remains irreducible to the propositional character of judgment. Schelling develops such insights further in his lectures on The Philosophy of Art (1802), two years after The System of Transcendental Idealism . Unlike Hegel’s lectures on Aesthetics where Hegel argues that “the work of art is a thing of the past” in so far as it no longer has an essential relation to the Absolute even though works of art will continue to be produced, and thus pass into the sobriety of philosophy’s Absolute Knowledge, Schelling sees works of art and philosophy as manifesting the differential mode of the Absolute where art retains an essential, singular and irreducible role.

b. Identity Philosophy

In 1795, Friedrich Hölderlin published an article called On Judgment and Being that has proved to be of decisive importance for the later development of German Idealism. In this small article Hölderlin attempts to think of an Absolute identity, a prior and originary ground of consciousness that cannot be grasped or known within the immanence of self-consciousness. Hölderlin calls this originary identity “being”( Seyn) which he distinguishes from Judgment ( das Urteil). Hölderlin here attempts to think of an originary identity that grounds the reflective judgment. According to Hölderlin this reflective judgment which is the unity of a disjunction, separation or difference between the subject and the object, must already presuppose an originary identity before judgment. In so far as judgment presupposes the difference between the subject and the object of consciousness, it must already be grounded in an identity. This identity is being (Seyn) which, because of its ground character, remains irreducible to the reflective consciousness. In order for judgment to be possible, it must be grounded in a principle that exceeds judgment itself. This originary identity is being which is before or without consciousness.

In his Identity philosophy, Schelling too attempts to move beyond the immanence of self-consciousness and the circle of reflective judgment. With this move, Schelling decisively breaks away from the Fichtean subjective Idealism. The question of ‘I’ is no longer the point of departure, unlike that of Fichte’s absolute ‘I’ that is not an inert substance but arises purely in the act of self-positing. Rather, here it is the question of consciousness as a result of a process which is to be grasped not merely from the side of the Subject of self-consciousness but from the other side as well. This relation between subject and object thus can no longer be grounded within self-consciousness itself but in an absolute indifference that is prior to this distinction and hence, that can only be presupposed but is never accessible to reflective judgment or to the categories of understanding. Unlike that of reflective philosophy, the question is no longer that of making a correspondence between the subject and the object of consciousness. Such a representational philosophy of correspondence is here abandoned. The problem is rather that of explaining the manifestation of a finite world from a ground that is forever excluded from the infinite chain of conditioned, finite, particular entities. In order not to fall into dualism, which Jacobi alludes is the dualism between the unconditioned ground on the one hand and the infinite chain of conditioned, finite entities on the other, Schelling has to explain the manifestation of the finite world out of its unconditioned ground, from an absolute indifference, without falling into the logic of reflective thinking which Hegel later uses to develop in his Phenomenology of Spirit. This is the emergence of the finite world of entities that are connected to each other in an infinite chain of predicates from an originary indifference which is unconditioned. This emergence is not a smooth transition but a qualitative leap, a diversion, a falling away (Abfall) from its originary ground. Later in his critique of Hegel, Schelling argues that such a leap cannot be understood on the basis of Hegelian modality of dialectical negativity that arrives at absolute knowledge only on the basis of the self-cancellation of the finite.

Perhaps the most lucid and systematic exposition of Schelling Identity philosophy will be found in his posthumously published lecture called The System of Philosophy in General and of the Philosophy of Nature in Particular (1804). Schelling gave this lecture during his brief years of stay at Würzburg. Schelling here begins with the proposition which according to him is the first presupposition of all knowledge, that is: “the knower and that which is known are the same”. This proposition immediately puts into question the correspondence theory of truth and knowledge that was dominant at that time. The correspondence theory of knowledge posits two principles – the subject and the object of knowledge – which are then sought to be reconciled in a higher synthetic principle. According to Schelling, once this dualism is posited, the possibility of knowledge itself becomes inexplicable. Therefore Schelling begins with an absolute identity of the known and the knower, an identity that cannot be posited within subjectivity. With this notion of absolute identity beyond subjectivity, Schelling definitely breaks with Fichte’s Subjective Idealism and Kant’s reflective philosophy. Distinguishing his Identitätssystem from both Empiricism and merely subjective Idealism, Schelling here introduces the notion of the Absolute that has proved to be of crucial importance for German Idealism in general. The absolute identity is the unconditional identity of the subject and the object, idea and Being, Ideal and Real both at once, immediately posited and not discreetly. As immediate knowledge of the absolute, this system of identity is distinguished from what Schelling calls “common sense understanding”.

The common sense understanding distinguishes conditional knowledge, which is synthetic, real knowledge from unconditional knowledge, which is analytic and thus is no real knowledge. Here common sense understanding comes to an irresolvable aporia: either I have real, objective knowledge, but then I renounce the unconditional; or, I have the unconditional in which case it is merely subjective and thus is no real knowledge. According to Schelling, this irresolvable aporia is the aporia of Kantian philosophy which Kantian dogmatism can never resolve. This demands a move beyond Kant’s critical philosophy. This move which inaugurates German Idealism consists of going beyond the mediated knowledge of the Absolute to the immediate knowledge of the Absolute which is an immediate affirmation of this affirmation. As immediate knowledge of the absolute, Reason is Absolute Knowledge. From this idea Hegel’s notion of the Absolute is not far. Unlike Kant’s regulative idea of Reason, Reason here is the idea of God as an immediate, absolute, unconditional identity. The immediate awareness of the Spirit of its absolute will which can never be further grounded in concept, is what Schelling calls in this essay ‘intellectual intuition’. It is intuition because it is not yet mediated by concept, and it is intellectual because it goes beyond the empirical in that it has as its predicate its self-affirmation. As the unconditional ground of all knowledge, ‘intellectual intuition’ does not belong even to inner sense. Thus what Fichte calls ‘intellectual intuition’ is no longer seen here as belonging to the inner sense but to the unconditional absolute which is beyond the circle of self-consciousness. “The fact of consciousness” is not originary, for there must already be a priori identity before differences come to manifest in consciousness. The essence of Reason can be said to be ‘intellectual intuition’ whose object is exclusively the absolute which is monolithic, one and only substance. By virtue of this affirmation, Reason recognizes “the eternal impossibility of non-being”. Being is not a predicate of God as something lying outside or exterior, but God and being is immediately, unconditionally one without duration. This absolute identity is infinite by virtue of its idea. Therefore God can neither be thought as the end result of the self-negation of difference, nor being involved in a process of emanation. The indivisibility and univocity of God is neither a numerical concept nor a concept of totality as aggregate unity of finite particulars. This is because the indivisibility and univocity of God is the ground for infinite divisibility in form or in accidents. How can the existence of finite, particulars be explained within Identitätssystem?

In regard to the absolute identity, these finite, particulars are surely non-being, non-ens, non-essentials that can neither subtract nor add anything to the essence of the being who is the absolute substance. The existence of the finite, particulars can only be understood, not as modification of essence, but as modifications in form. They are non-being in respect to the universal which is absolute identity, but considered independently, they are not completely devoid of being. They are in part being and in part non-being. As such they are “real” or “concrete” things, irreducibly finite, particular, multiple, whose ground of existence does not lie within themselves but in that absolute identity of Being and essence. Schelling here deduces the finitude of particulars which ‘common sense understanding’ calls ‘actuality’, not as a process of emanation from the absolute identity, but as negativity that adheres in all finite things. Since these finite things cannot have positivity of being within themselves, they must therefore always relate themselves to other finite things, all sensuous cognition of them can only be non-cognition. Schelling here radically departs from Kant. For Kant all cognition is cognition of the sensible but not of the supersensible. By contrast Schelling argues that all of our sensory knowledge is only a privation of knowledge, or rather, “a negation of knowledge”. Hegel argues in a similar manner in Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) where he shows in a dialectical manner, the vanity of the supposed certitude of sensuous cognition.

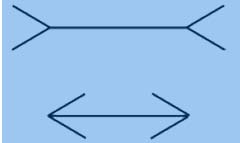

One can present the schema of Schelling’s Identitätssystem as follows. God as absolute identity is an essential, qualitative identity. Absolute indifference follows from this essential identity of the absolute. Therefore, absolute indifference is not in-itself essential but a quantitative identity. There is thus a difference between absolute identity and absolute indifference. The opposition between real and ideal, subject and object arises out of this indifference. This is the birth of the finite world. Schelling here introduces the theory of potencies in triplicates that are “the necessary modes of appearances of the real and ideal universes”. While the potencies in triplicates are “the necessary modes of appearances” of the finite universes, they are not applicable to the absolute identity. The absolute identity is thus without potency or devoid of power. The potencies are those modes of appearances that make manifest the non-essential. Therefore they all have equal dignity in relation to the absolute. No potency has priority over the others temporally, for they are not posited successively in a genetic sequence but simultaneously, with equal primordiality. As such, they constitute a circle where all the potencies are posited together but not in an equal manner. Each time the potencies are posited, a particular potency predominates, subjugating the others to their relative non-being. At another time another potency predominates in an alternate manner, always returning to the same and always going away, always being attracted and repulsed, always contracted and expanded in an alternate, circular manner. In this alternating, rotatory movement of potencies the Real principle comes first as the ground or condition of the Ideal Universe. The Ideal universe then overcomes the Real principle, its conditioning and grounding factor, by relegating it to its relative non-being. Only the higher synthetic principle can unify both the Real and Ideal universes by inhering in both and yet separating each from the other. Schelling presents the theory of potency in the following formula:

A3

—————–

A2 = (A=B)

Where:

A=B : The domination of the Real or affirmed. It is A1

A2 : The domination of the Ideal

A3 : Indifference between the other two

With the theory of potencies Schelling explains the existence of the finite universes which are originally one. Their existence is neither completely being nor nothing, but a relative being and relative non-being. As relative being and relative non-being, potencies exceed each time from the immanence of self-presence. They never arrive at the absolute equilibrium of forces without ceasing themselves to be potencies. The circle of the potencies never comes to standstill, or that they do not come out of the circle unless a will superior to this circle of the conditioned existence breaks in.

Three years after this lecture, Hegel published his magnum opus Phenomenology of Spirit. In his Phenomenology of Spirit published in 1807, Hegel apparently criticizes Schelling’s notion of the Absolute indifference as “the night where all cows are black”. In a letter to Hegel, Schelling asks Hegel to clarify in the Preface to the Phenomenology whether this criticism is applied to him or to others who misuse Schelling’s ideas. Hegel did not incorporate this clarification in the subsequent edition of Phenomenology that the criticism is applied, not to Schelling, but to others. This led to the break in the friendship between the two philosophers who shared the same room at Tübingenstift. While this friendship was profoundly important and fruitful for both of them, the bitterness proved to be equally decisive for the development of their singular modes of thinking, one leading to the task of systematic completion of the metaphysics of the Subject, the other leading to the attempt to inaugurate a new thinking beyond such a metaphysics of the Subject.

c. The Middle period

Published in 1809, Philosophical Inquiries into the Nature of Human Freedom is perhaps the most important book that Schelling published in his life time. Along with Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, Fichte’s Science of Knowledge, and Kant’s Critique of Judgment, this essay is one of the greatest philosophical achievements of the late 18th and 19th century Germany. Published immediately before the death of Caroline, it evokes “a deep, unappeasable melancholy” that adheres to all finite beings. Here Schelling does not pose the question concerning the essence of human freedom as the dialectical problem between nature and freedom. Freedom does not appear here as the free exercise of the rational Subject’s will to mastery over its sensuous nature, but as the capacity to do evil. The question thus posed is no longer one question amongst others but the metaphysical question concerning the possibility of a system of freedom. On the one hand, freedom appears to be that which cannot be included within a system at all; on the other hand, the demand of Idealism that there must be a system without which nothing is adequately comprehensible is not to be renounced. The essay attempts to reconcile these two incommensurable demands: the demand of the unconditionality of freedom that grounds being and the demand of the grounding act of the system. This attempt at the system of freedom arose in the wake of what came to be known as the “pantheism controversy”.

The pantheism controversy is centred on the supposedly atheistic figure of Spinoza. During the late 18th century, and early 19th century, the dominant understanding of Spinoza was that of a pantheist and consequently an atheist. It is understood that within the pantheistic system of Spinoza’s ethics wherein God is immediately identified with the world, there is no place for the affirmation of God as unconditional reality. If the world is only a totality of conditioned, finite beings, then the unconditioned existence of God cannot be understood to be immediately identifiable with the world, and consequently with any dogmatic, rational system. In the famous pantheism controversy, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi attempted to show that a system of rational knowledge never arrives at the unconditioned since, for such a system, the unconditioned can only arise as a result of a process where the one conditioned leads to other conditioned in an infinite chain of negativity. To be properly concerned with the unconditioned, one must begin with the unconditioned itself which no rational knowledge ever attains. For Jacobi it is only the leap of faith beyond the system of rational knowledge that enables us to open to the unconditionality of the absolute being. Therefore all system of rational knowledge for Jacobi is nihilism. Jacobi thereby becomes the first to use the word “nihilism” that arose in the context of the pantheism controversy.

Schelling here agrees with Jacobi about the limit of purely rational attainment of the unconditioned. Schelling, however, disagrees with Jacobi’s use of a limited and restricted notion of ‘system’ and ‘freedom’, along with Jacobi’s restricted use of the metaphysical and logical notion of judgment. In the Freedom essay Schelling attempts to re-interpret the logical and metaphysical notion of judgment in such a manner that it opens up to the unconditioned character of freedom without renouncing the demand of a system. Such a system must, on the one hand, be other than a purely formal, lifeless realism of Spinoza; and on the other hand, it must be otherwise than a conventional system of idealism that reduces the dynamic character of freedom and the world into pure rational necessity. Only a dynamic notion of the system that affirms the exuberance of life and the generosity of freedom can truly be system. The formal, rational notion of freedom as the intelligible principle that overcomes sensuous impulses must be opened to the ontological question of the beings in their becoming. The question of judgment is thus no longer merely a formal logical question but the question of the jointure, or bond of beings. This bond or jointure of beings is grounded in freedom which, understood in more originary manner, is not arbitrary free will but that belongs together with highest necessity. This jointure of beings – the infinite, creative being of God and the finite, created being called ‘man’ – must be essentially a free relation, a relation that is governed by freedom which in the highest sense is also necessity. If man is free in a certain manner, then this manner is also the manner of man’s individuation. This is to say that to the extent that man is individuated by freedom, man’s freedom is distinguishable from the absolute freedom of the infinite, eternal being called God. This peculiar essence of human freedom is the capacity to do evil.

According to Schelling, the human is distinguished from the eternal creative God by the specificity of his freedom which is essentially and inextricably a finite freedom. God is the being whose condition, though never completely immanent, can be actualized in its very existing. On the other hand, the finite being can never actualize itself completely because the ground of its existence remains inappropriable. This is the source of the fundamental melancholy of all finite beings. The distinction between the absolute freedom of the eternal being and the finite freedom of the mortal can be better understood with the help of Schelling’s distinction between the ground of existence and existence itself. This is not a formal distinction between sensuous nature and intelligible will, but a dynamic distinction of freedom. Eternal or finite, each being is a jointure of the ground of existence and existence itself. In the eternal, creative being, this jointure is indissoluble. In the mortal, however, there can occur dissolution of this jointure. It is the possibility of the dissolution of the principles that explains the finitude of the finite being, and the freedom of this finite being. The human is essentially finite being, and only such a finite being is capable of evil. Therefore evil is neither divine nor beastly but essentially belongs to the human freedom. Evil has this peculiar, specific relation to human finitude. Unlike the beasts in whom the jointure of the principles is governed by necessity, and unlike the divine in whom the jointure of the principles is indissoluble, human freedom partakes of the divine freedom and is yet separated by an abyss. According to Schelling, this abyss is the possibility of dissolution of the principles.

In the dynamic freedom there are two oppositional principles that never reach equilibrium. In the coming to existence of the finite being there adhere these oppositional principles. There is the dark principle which is the principle of ground, and there is the ideal principle of light. The dark principle that operates in the realm of history as the principle of particularity is the principle of evil. Man is the finite being that unites in himself both of these principles in an equal measure. Since the nexus (band) of these principles in him is free and not governed by necessity, man is free to bring permutation to this nexus. Therefore what ought to remain as mere condition of existence, as mere principle of particularity, man can seek to elevate to totality or to universal domination. Out of this self-affirmation of the finite being who in this self-affirmation seeks to abnegate its very finitude, there arises evil. Thus while the possibility of evil is given to man in the coming into existence of this being, to actualize this principle of possibility is the work of human freedom. As mere ground, this principle is the very source of creative joy and affirmation of life, but elevating it into the universality or totality results into the most terrible form of evil that seeks to negate any form of its life-affirmative character. Thus the source of life and the origin of evil is grounded in the same principle. This principle is the human freedom whose origin remains unfathomable for man. According to Schelling, this unfathomable, inappropriable, unconditional freedom ought to remain inappropriable and unconditional, for the human creates a conditioned world on the basis of the unconditioned freedom. This conditioned world is history. By beginning this new “covenant”, man partakes the creativity of the divine freedom. This is the source of creative joy for the human, for through this creative act of human, the world of nature is redeemed. But in his vain arrogance and in his self-affirmation that is pushed to the point of absolutization and totalization, the human seeks to negate the finite character of his freedom and thereby seeks to elevate the principle of particularity to the universal domination. Herein lays the evil when the non-being, which is for that matter is not completely devoid of being, seeks to attain the complete, absolute being. Evil is therefore neither being nor nothing, but non-being’s malicious hunger for being. Therefore power of evil cannot be said to be the power of being. It is rather the power of non-being that seeks to devour itself and is never satisfied at any point, because it never reaches being without a remainder of non-being. More it does not reach being, more self-consuming becomes its lust. According to Schelling such is the character of evil.

In The Ages of the World which was written between 1809-1827 and is found in various incomplete versions, Schelling develops a narrative method that seeks to recount the stages of the world’s becoming through the agonal movement of conflictual forces. This is the germ of Schelling’s theory of potencies. The world as it exists has its ground in a dark, unfathomable past which no work of human reason can ever elevate into thought. This non-reason is not irrationality that is opposed to reason nor is it the negation of the possibility of reason but the ground of reason. Human reason thus exists only as a “regulated madness”. On account of its immanent force alone the human reason cannot attain the unconditioned which is the realm of absolute freedom. The emergence of the world-order is not seen as an immanent order ruled by the necessary principles of reason but has its source in an absolute, unconditional freedom. This freedom can arrive to the finite, mortal being as a gift. Man can never master this gift, because it opens man to his historicity. The essence of history is freedom. “The ages of the world” thus arises out of the unconditional character of freedom. This principle of freedom manifests itself in the agonal movement of contradictory forces, one repulsive and the other attractive. It is this agonal movement of oppositional forces that makes possible the emergence of “the ages of the world” out of the unconditional. This unconditional is that which cannot be further grounded in thought or in self-consciousness, it is what Schelling in his Freedom essay calls “the indivisible remainder” that constantly solicits from finite human beings ‘awe’ or ‘respect’.

Here as elsewhere Schelling’s thought wrestles with the question of the unconditioned. If there is anything that is singular to Schelling’s whole of philosophy, and that unifies Schelling’s often discontinuous philosophical career, it is this question of the unconditioned. Schelling does not explain the existence of the world with the help of logical categories. For Schelling, a rational system constitutive of logical categories cannot explicate the facticity or actuality of the world. It is the unconditional character of freedom whose ground is groundless (Abgrund), this freedom alone opens the world. Therefore there is always something excessive about freedom. In many texts, especially in his 1797 treatise, Schelling evokes a freedom which is not only a promise for the human but also a danger (Gefahr). “The ages of the world” is grounded by a condition which is excessive and unthinkable. The human belongs to the “un-pre-thinkable” ( Unvordenkliche). This is a promise as well as danger. Schelling evokes this excess to explain the possibility of the world and finite existence. This unconditional excess makes the world and being-in-the world as essentially finite and irreducibly mortal. It is this aspect of Schelling’s work that has most profoundly influenced the twentieth century philosophers like Franz Rosenzweig and Martin Heidegger.

d. Positive Philosophy

On 14 November 1831 Hegel died in Berlin. In 1840 Schelling was called to the now vacant chair in Berlin to replace Hegel. The following year Schelling began his lectures on “positive philosophy” (Positivphilosophie) which was attended by Kierkegaard, Bakunin, Humboldt and Engels. These lectures were delivered in three phases: Grounding of Positive Philosophy that introduces and grounds Positive Philosophy vis-à-vis the history of Negative Philosophy from Descartes onwards, followed by Philosophy of Mythology (Philosophie der Mythologie) and Philosophy of Revelation ( Philosophie der Offenbarung).

Schelling’s grounding of Positive Philosophy begins with the distinction between the “what” of being and “that being”. “What” of being is being as essence and “that” being is the contingent being’s pure actuality of existence. This actuality is not an attribute of being but its existentiality, the very facticity of its coming into being. From here comes the distinction between a negative philosophy, that is, the rational philosophy that is essentially concerned with the essence of being (its ‘what’ character) and the positive philosophy that is concerned with the pure actuality of the existence of “that” being which comes into its being. Such a being (“that” being) is not a settled entity that is given, but that which comes into being . Schelling calls such a coming into being, existence. Since this coming into being is not a finished entity but yet becoming and always contingent, it cannot be grasped in the concept. Therefore existence and movement cannot be a logical category. There is a concept only if a being already exists, for by definition concept can only grasp the essence of being which in turn is possible if such a being already exists. Understood in this sense, negative philosophy is not concerned with the facticity of something that exists at all. Therefore it is not concerned with the question “why something exists at all?” The negative philosophy is rather concerned with the question: if and if something exists, what is its essence, what is the “being” character of this being irrespective of the problem whether such a being exists as “this” being at all.

For example, when Kant argues against the ontological proof of God, he argues neither for the existence of God nor for its non-existence. He only argues that the concept of God is not extendable to the existence of God because ‘existence’ cannot be predicated. In so far as ‘existence’ cannot be predicated, its actuality or facticity can only be for rational philosophy a presupposition. This presupposition is a point of beginning whose existence can only be deduced only if such an existence is already granted; only if such and such a being has already revealed itself. What then Kant’s philosophy shows, for Schelling, is the limit of negative philosophy, a limit that constitutes the possibility of negative philosophy. Schelling does not contest the possibility of negative philosophy, but precisely demands it however, on the condition that it recognizes this limit that is constitutive of it and does not pretend to be able to constitute itself as absolute system that includes the concept as well as existence of being. What Schelling finds problematic in Hegel is not that there should not be negative philosophy, but of Hegel’s claim to include existence in a system that is logical and purely negative system. For Schelling, Hegel’s extension of his negative notion of system to the Absolute totality without outside is without justification. For Schelling there always remains a remainder of such a system of negativity, which is the positivity of existence. Hegel’s system is founded upon purely negative relation of the finite being in relation to other finite beings where the unconditioned is supposed to be reached as a self-negation of negation. According to this conception, the unconditioned is the end result of a process of the self-cancellation of finite, conditioned entities. As early as 1804 in a lecture in Würzburg on The System of Philosophy in General Schelling contests this idea of the absolute as the end result of a process of the self-negation of finitude. According to Schelling, such a system is based upon a false premise and a presupposition. It presupposes to have reached the unity of being and thought, while it reaches such a unity merely in thought that means, only from negative side. It leaves out the pure actuality of existence whose unconditional character of its being cannot be merely the result of a dialectical process of the self-cancellation of finitude. Unlike Hegel’s claim, a purely negative philosophy cannot be presupposition-less. It presupposes what it cannot incorporate within its systemic edifice. This limitation of negative philosophy demands a positive philosophy that begins with the unconditionality of existence, with a prius whose existence can only be proved posteriori once there is a manifest world. Schelling called such a positive philosophy, “metaphysical Empiricism”. Hence the idea of a positive philosophy is where the ground is a presupposition. This presupposition is the unconditional existence of being whose pure actuality no rational knowledge based upon potentiality can ever attain. While the philosophical concept that is essentially concerned with essence can only elaborate the possibility of being, the actuality of being itself is beyond such categorical cognition, for the existence of this being exists as absolute freedom and not as a necessary consequence of a concept.

Here the limit of the Idealist notion of system is reached. Schelling in these lectures shows that the (Hegelian ) notion of the Subject presupposes as its condition that which cannot be further grounded in the Subject itself. One then has to begin from the pure actuality of existence, from a facticity, which is already always before self-consciousness and before thought’s ability to grasp it in the concept. This immemoriality of the origin is the “exuberance of being” that elicits from us awe or respect ( Achtung), because it exposes us to the Infinite that unconditionally and groundlessly exists. It thereby exposes us to our own finitude and mortality.

3. Influences

How deeply Schelling’s later philosophy has influenced Kierkegaard cannot be shown by quoting Kierkegaard or from Kierkegaard’s self-understanding. This can better be shown by understanding Kierkegaard’s anti-systematic notions of “existence”, “temporality” and “finitude” that he understands to be irreducible to the general order of the system. Like Schelling, Kierkegaard understands the question of existence as the highest question of philosophy. There is in existence something that cannot be grasped in the predicative. Likewise, in the realm of history there is a preponderant mass of contingencies that cannot be completely and exhaustively accounted by the speculative dialectical logic. The Post-Schellingian philosophies that are concerned with this problem have the source of their inspiration in Schelling’s later works. For Schelling neither history nor existence is a homogenous process leading straight, necessarily, to a telos of absolute knowledge by irresistible law which is auto-generative and anonymous. History is rather a field of polemos where agonal forces are at work. Kierkegaard’s The Concept of Anxiety begins with a Schellingian note. Kierkegaard here argues, in a manner that recalls Schelling’s critique of Hegel, that the notion of movement does not allow itself to be thought within the immanent speculative logic of Hegel, for the true movement presupposes transcendence which by definition a logical category cannot grasp. The task of Kierkegaard’s philosophy is to open towards an Archimedean point outside totality, or outside the general, normative order of validity. That point cannot be attained within the realm of the ethical, that is, within the homogenous order of universal norms, but in a “quantum leap” of faith. That leap of faith must pass through an existential experience of anxiety (Angst) which no phenomenology of spirit can thematize.

This anxiety has family resemblance with Schelling’s notion of anxiety of the mortal who constantly flees from the fire of the centre and takes shelter in the periphery. In Schelling as well as in Kierkegaard, especially in his Fear and Trembling, this anxiety manifests the irreducible finitude of the mortal being who is seized by the gaze of the wholly other, the divine, holding his hand, tearing him out of the totality of finite knowledge. In his Concluding Unscientific Postscript Kierkegaard attempts to open this universal order of the ethical to the notion of subjectivity, the subjectivity of that singular individual for whom transcendence of the wholly other is an existential interest. This existential interest, argues Kierkegaard, cannot be addressed within the immanent order of the system. One of the most prominent tendencies of the post-Schellingian philosophy is this question of existence from the religious point of view. For Schelling himself the question of religion remains irreducible to the rational-logical system of knowledge. The transcendence of the absolute cannot be reduced to a theodicy of history. As early as 1804, Schelling warned in his Philosophy and Religion against the danger of the acts of legitimacy by the earthly power in the name of the embodiment of the divine in the profane body. Religion for Schelling, as for Kierkegaard remains irreducible to the violence of a historical reason that constantly evokes a theological foundation for the justification of its domination. As against this theologico-political foundation, Kierkegaard evokes the whole other God. Thus religion cannot be used as the foundation of the profane in order to legitimize the power of earthly sovereignty, because religion essentially opens us to a non-foundation that eternally delegitimizes any earthly power, like the power of the State. In his 1804 lecture Philosophy and Religion and in his Stuttgart lectures of 1810, Schelling raises this important theologico-political question that has profound significance for our contemporary historical world. The recent upsurge of the question of political theology attempts to go back to Schelling to see how Schelling helps us to think of a critique of historical reason.

Such a question is pursued further by Franz Rosenzweig, a German Jewish philosopher who is contemporary of Martin Heidegger. Rosenzweig’s first scholarly work was his doctoral thesis on Hegel called Hegel and the State. In the wake of his horror of the First World War, Rosenzweig soon abandoned Hegelianism; his The Star of Redemption, which he wrote on post cards to his mother when he was in the Balkan Front, is an anti-Hegelian work. In this book, that evokes Schelling’s later works as one of the main sources of inspiration, Rosenzweig envisions the messianic notion of history and redemption beyond the closure of a historical-speculative reason. This remarkable book begins with the question of existence which he takes from Schelling’s later works. It is the notion of the individual, finite existence whose fear of death cannot be consoled by the concept of the universal history. This demands opening up the closure of the universal historical reason to the arrival of redemption that is always to come. This eternity which is always to come, that alone can redeem the violence of a historical reason, does not itself belong to the “Philosophy of the All”. Rosenzweig’s critique of “the philosophy of the All” begins with Schellingian critique of Hegel, that existence precedes thought and thus it cannot be enclosed within the All. It is what falls outside totality or system, and in this manner opens the world to the messianic event of pure future. The messianic arrival of eternity does not allow itself to be reduced to the theological foundation of the profane order, like the power of the State. Thus the State is no longer an expression of the Absolute. Like Schelling, Rosenzweig’s later works are deeply suspicious of the theodicy of history that legitimizes the political sovereignty of the State.

The question of existence is important for Martin Heidegger’s early philosophical works. What Heidegger calls in his early works “hermeneutics of facticity” has resonance with Schelling’s notion of actuality of “that”, the pre-predicative, pre-conceptual and pre-categorical disclosure. The existential analytic of Dasein that Heidegger elaborates in his Being and Time and his deconstruction of the metaphysical foundation of logic has inspiration in Schelling’s attempt to open the system of negative philosophy to the more originary revelation of being. Schelling’s positive philosophy seeks to release philosophy beyond its metaphysical foundation in the logic of the thinkable to a disclosure that can only be shown a posteriori . In this sense Schelling’s metaphysical empiricism is at once an exit from the metaphysics founded upon the notion of the predicative truth. What both Heidegger and Rosenzweig have sought to complete is this exit from metaphysics. Heidegger’s 1936 lecture on Schelling shows the real importance of Schelling’s thinking for him.

The exit from metaphysics is a fundamental problem even for Marx. Ernst Bloch, whom Jürgen Habermas calls “Schellingian Marxist”, combines a certain version of Marxism and messianism that envisions a utopian fulfilment oriented towards the “not yet”. His The Spirit of Utopia and his later work The Principle of Hope evoke a notion of history that is disruptive, opening to the “not yet”, a fundamental affirmation of future which Schelling always insisted as the very creative, free task of philosophy. While Schelling has attempted to open the radical notion of future in a certain eschatological-theological manner, Bloch’s messianism is essentially an atheistic eschatology.

Schelling’s influence is seen to be growing in our contemporary philosophical world. Thus Jean Louis Chrétien, the French philosopher, has drawn on Schelling from a certain phenomenological perspective. In his Unforgettable and the Unhoped for, Chrétien is concerned with the immemoriality of a promise that arrives from the extremity of time, from an eschatos of future always to come. Chrétien draws here on Schelling’s notion of the eternal past which has not come to pass but that is always a past, an immemorial past that, being the principle of foundation, always opens the world to its futurity. Schelling indeed develops such a notion of an immemorial past in his The Ages of the World. Like Schelling in his various texts, Chrétien too evokes Plato’s notion of Anamnesis as remembrance, not of what has passed, but what has immemorially opened us to truth. What has found us, the excess that opens us to the world, is immemorially lost. For both Schelling and Chrétien, this is not the occasion of despair but the occasion of a creative freedom and the possibility of future. In recent years the Anglophone philosophical world has been witnessing increased attention to Schelling’s works. This shows the continuing relevance of Schelling in our contemporary historical existence. Schelling’s philosophy has come to be interpreted and understood as a philosophy of affirmation and a philosophy of the exuberance of life as against petrified system of concepts. Jason Wirth’s recent work on Schelling rightly emphasizes the contemporaneity of Schelling for our concerns: our ethical concern with the primacy of Good over truth, the affirmation of life beyond the instrumental use of Reason, the affirmation of the more originary ecstatic temporality, and our deep ecological concerns. The ‘unconscious’ has psychoanalysis speaks of, evokes the notion of ‘unconscious’ in Schelling, the abyss that cannot be further grounded, and hence is unground. In Jacques Lacan’s term, it is the Real that never stops haunting, destabilizing and disturbing the symbolic order of the world. “The indivisible remainder” that Schelling speaks of in his 1809 Freedom essay is that element of eternal nature as ground that never ceases de-constituting the cultural-historical order of totality. The symbolic order of a restrictive Reason never reaches totality, but always opens to an eternal remnant outside. This question has profound importance of Schelling for our time.

4. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

- Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling’s Sämmtliche Werke, ed. K.F.A. Schelling, I Abtheilung Vols. 1-10, II Abtheilung Vols. 1-4, Stuttgart: Cotta, 1856-61.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling, Ausgewählte Schriften, 6 Vols., ed. Manfred Frank, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp 1985.

- Aus Schellings Leben. In Briefen (three volumes), Adamant Media Corporations, 2003.

- The Unconditional in Human Knowledge: Four early essays 1794-6 , trans. F. Marti, Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1980.

- Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature: as Introduction to the Study of this Science , trans. E.E. Harris and P. Heath with an introduction R. Stern, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1797/1988.

- System of Transcendental Idealism, trans. P. Heath with an introduction by M. Vater, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1800/1978.

- Bruno, or On the Natural and the Divine Principle of Things , trans. with an introduction by M. Vater, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1802/1984.

- The Philosophy of Art , Minnesota: Minnesota University Press, 1802-03/1989.

- On University Studies , trans. E.S. Morgan, ed. N. Guterman, Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1803/ 1966.

- Philosophical Inquiries into the Nature of Human Freedom, trans. With an introduction by J. Gutmann, Chicago: Open Court, 1809/1936.

- Clara : or On Nature’s Connection to the Spirit World, trans. Fiona Steinkamp, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1811/2002.

- The Ages of the World, trans. Jason M. Wirth, Albany: State University of New York, 1811-15/2000.

- The Ages of the World , trans. F. de W. Bolman, jr., New York: Columbia University Press, 1811-15/1967.

- ‘The Deities of Samothrace’ , trans. R.F. Brown, Missoula, Mont.: Scholars Press, 1815/1977.

- On the History of Modern Philosophy, trans. Andrew. Bowie, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1833-4/1994.

- Philosophie der Offenbarung . ed. M. Frank, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1841-2/1977.

- Historical-Critical Introduction to the Philosophy of Mythology, trans. Richey, M., Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2007.

- The Grounding of Positive Philosophy: the Berlin Lectures , trans. Bruce Matthews, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2008.

- Philosophy and Religion , Spring Publications, 2010.

- Idealism and the Endgame of Theory , trans. Thomas Pfau , Albany: State University of New York, 1994.

- Philosophy of German Idealism: Fichte, Jacobi and Schelling, ed. Ernst Behler , Contuum, 1987.

b. Secondary Sources

- Beach, Edward Allen, The Potencies of God(s): Schelling’s Philosophy of Mythology, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

- Behun, William A. The Historical Pivot: Philosophy of History in Hegel, Schelling and Hölderlin , Triad Press, 2006

- Beiser, Frederick C., German Idealism: Struggle Against Subjectivism , Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- Bowie, Andrew, Aesthetics and Subjectivity: from Kant to Nietzsche, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990.

- Bowie, Andrew, Schelling and Modern European Philosophy: An Introduction, London: Routledge, 1993

- Brown, Robert F., The Later Philosophy of Schelling: The Influence of Boehme in the Works of 1809-1815 , The Associated University Press, 1977

- Courtine, Jean-Francois , Extase de la raison. Essais sur Schelling, Paris, Galilée, 1990

- Distaso, Leonardo V., The Paradox of Existence : Philosophy and Aesthetics in the Young Schelling, Springer, 2010

- Esposito, Josephe L., Schelling’s Idealism and Philosophy of Nature, Associated University Press, 1977

- Fackenheim, Emil, The God Within: Kant, Schelling and Historicity , ed. John W. Burbridge, University of Toronto Press, 1996

- Frank, Manfred, Der Unendliche Mangel an Sein, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1975

- Frank, Manfred, Eine Einführung in Schellings Philosophie, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1985

- Frank, Manfred, Selbstbewußtsein und Selbsterkenntnis, Stuttgart: Reclam, 1991

- Frank, M. (ed). with Kurz, G., Materialien zu Schellings philosophischen Anfängen, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1975

- Freydberg, Bernard, Schelling’s Dialogical Freedom Essay: Provocative Philosophy Then and Now , State University of New York Press, 2009

- Geldhof, J, Revelation, Reason and Reality: Theological Encounters with Jaspers, Schelling and Baader, Peeters, 2007

- Goudeli, Kyriaki, Challenges to German Idealism: Schelling, Fichte and Kant, Palgrave Macmillan, 2003

- Grant, Ian Hamilton, Philosophies of Nature After Schelling, Continuum, 2008

- Hegel, G.W. F., The Difference between Fichte’s and Schelling’s System of Philosophy, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1977

- Heidegger, Martin, Schellings Abhandlung über das Wesen der menschlichen Freiheit, Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1971. Schelling’s Treatise on the Essence of Human Freedom, trans. Joan Stambaugh, Athens: Ohio University Press, 1985

- Heidegger, Martin, Die Metaphysik des Deutschen Idealismus (Schelling), Frankfurt: Klostermann, 1991

- Henrich, D. Selbstverhältnisse, Stuttgart: Reclam, 1982

- Horn, Friedemann , Schelling and Swedenborg: Mysticism and German Idealism, trans. George F. Dole , Swedenborg Foundation Publishers, 1997

- Jaspers, Karl, Schelling: Größe und Verhängnis, Munich: Piper, 1955

- Kierkegaard, Søren, The Concept of Irony/Schelling Lecture Notes : Kierkegaard’s Writings Vol 2, Princeton University Press, 1992

- Kosch, Michelle, Freedom and Reason in Kant, Schelling and Kierkegaard, Oxford University Press, 201

- Lauer, Christopher, Suspension of Reason in Hegel and Schelling, Continuum,201

- Limnatis, Nectarios G., German Idealism and the Problem of Knowledge: Kant, Fichte, Schelling and Hegel , Springer, 2010

- Marx, W. , The Philosophy of F.W.J. Schelling: History, System, Freedom, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984

- Norman, Judith and Alistair Welchman , ed. New Schelling , Continuum, 2004

- O’Meara, Thomas, Romantic Idealism and Roman Catholicism: Schelling and the Theologians, University of Notre Dame Press, 1982

- Shaw, Davin Jane , Freedom and Nature in Schelling’s Philosophy of Art , Continuum, 2011

- Snow, Dale E., Schelling and the End of Idealism, Albany: SUNY Press, 1996

- Tillich, Paul, Mysticism and Guilt Consciousness in Schelling’s Philosophical Development , Bucknell University Press, 197

- Tilliette, X. , Schelling une philosophie en devenir, Two Volumes, Paris: Vrin, 1970

- White, A., Absolute Knowledge: Hegel and the Problem of Metaphysics, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1983a

- White, A., Schelling: Introduction to the System of Freedom, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1983b

- Wirth, Jason, The Conspiracy of Life: Meditations on Schelling and His Times, New York: State University of New York Press, 2003

- Wirth , Jason, (ed.),Schelling Now: Contemporary Readings, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2004

- Zizek, Slavoj ,The Indivisible Remainder: An Essay on Schelling and Related Matters, London: Verso, 1996.

Author Information

Saitya Brata Das

Email: satyadx@yahoo.com

The University of Delhi

India

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, was a physiologist, medical doctor, psychologist and influential thinker of the early twentieth century. Working initially in close collaboration with Joseph Breuer, Freud elaborated the theory that the

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, was a physiologist, medical doctor, psychologist and influential thinker of the early twentieth century. Working initially in close collaboration with Joseph Breuer, Freud elaborated the theory that the

Jerry Fodor was one of the most important philosophers of mind of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In addition to exerting an enormous influence on virtually all parts of the literature in the philosophy of mind since 1960, Fodor’s work had a significant impact on the development of the cognitive sciences. In the 1960s, along with Hilary Putnam, Noam Chomsky, and others, Fodor presented influential criticisms of the

Jerry Fodor was one of the most important philosophers of mind of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In addition to exerting an enormous influence on virtually all parts of the literature in the philosophy of mind since 1960, Fodor’s work had a significant impact on the development of the cognitive sciences. In the 1960s, along with Hilary Putnam, Noam Chomsky, and others, Fodor presented influential criticisms of the

Organicism is the position that the universe is orderly and alive, much like an organism. According to

Organicism is the position that the universe is orderly and alive, much like an organism. According to