Locke: Ethics

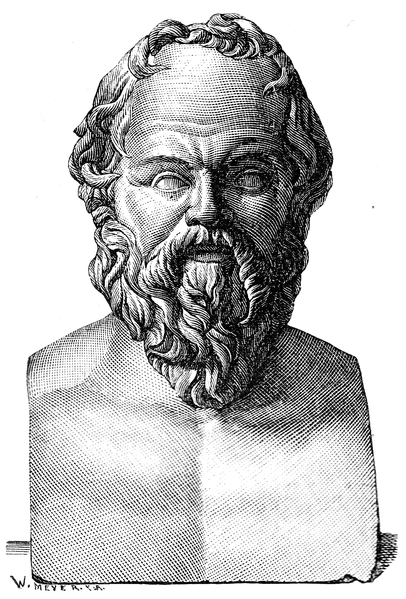

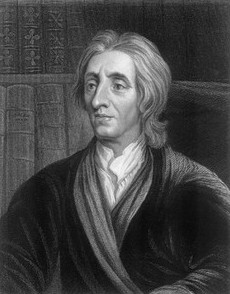

The major writings of John Locke (1632–1704) are among the most important texts for understanding some of the central currents in epistemology, metaphysics, politics, religion, and pedagogy in the late 17th and early 18th century in Western Europe. His magnum opus, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) is the undeniable starting point for the study of empiricism in the early modern period. Locke’s best-known political text, Two Treatises of Government (1693) criticizes the political system according to which kings rule by divine right (First Treatise) and lays the foundation for modern liberalism (Second Treatise). His Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) argues that much civil unrest is borne of the state trying to prevent the practice of different religions. In this text, Locke suggests that the proper domain of government does not include deciding which religious path the people ought to take for salvation—in short, it is an argument for the separation of church and state. Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) is a very influential text in early modern Europe that outlines the best way to rear children. It suggests that the virtue of a person is directly related to the habits of body and the habits of mind instilled in them by their educators.

The major writings of John Locke (1632–1704) are among the most important texts for understanding some of the central currents in epistemology, metaphysics, politics, religion, and pedagogy in the late 17th and early 18th century in Western Europe. His magnum opus, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) is the undeniable starting point for the study of empiricism in the early modern period. Locke’s best-known political text, Two Treatises of Government (1693) criticizes the political system according to which kings rule by divine right (First Treatise) and lays the foundation for modern liberalism (Second Treatise). His Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) argues that much civil unrest is borne of the state trying to prevent the practice of different religions. In this text, Locke suggests that the proper domain of government does not include deciding which religious path the people ought to take for salvation—in short, it is an argument for the separation of church and state. Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) is a very influential text in early modern Europe that outlines the best way to rear children. It suggests that the virtue of a person is directly related to the habits of body and the habits of mind instilled in them by their educators.

Although these texts enjoy a status of “must-reads,” Locke’s views on ethics or moral philosophy have nowhere near the same high status. The reason for this is, in large part, that Locke never wrote a text devoted to the topic. This omission is surprising given that several of his friends entreated him to set down his thoughts about ethics. They saw that the scattered remarks that Locke makes about morality here and there throughout his works were, at times, quite provocative and in need of further development and defense. But, for reasons unknown to us, Locke never indulged his friends with a more systematic moral philosophy. It is thus up to his readers to stitch together his fragmented remarks about happiness, moral laws, freedom, and virtue in order to see what kind of moral philosophy is woven through the texts and to determine whether it is a coherent position.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Good

- The Law of Nature

- Power, Freedom, and Suspending Desire

- Living the Moral Life

- References and Further Reading

1. Introduction

While Locke did not write a treatise devoted to a discussion of ethics, there are strands of discussion of morality that weave through many, if not most, of his works. One such strand is evident near the end of his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (hereafter: Essay) where he states that one of the most important aspects of improving our knowledge is to recognize the kinds of things that we can truly know. With this recognition, he says, we are able to finely-tune the focus of our enquiries for optimal results. And, he concludes, given the natural capacities of human beings, “Morality is the proper Science, and Business of Mankind in general” because human beings are both “concerned” and “fitted to search out their Summum Bonum [highest good]” (Essay, Book IV, chapter xii, section 11; hereafter: Essay, IV.xii.11). This claim indicates that Locke takes the investigation of morality to be of utmost importance and gives us good reason to think that Locke’s analysis of the workings of human understanding in general is intimately connected to discovering how the science proper to humankind is to be practiced. The content of the knowledge of ethics includes information about what we, as rational and voluntary agents, ought to do in order to obtain an end, in particular, the end of happiness. It is the science, Locke says, of using the powers that we have as human beings in order to act in such a way that we obtain things that are good and useful for us. As he says: ethics is “the seeking out those Rules, and Measures of humane Actions, which lead to Happiness, and the Means to practice them” (Essay, IV.xxi.3). So, there are several elements in the landscape of Locke’s ethics: happiness or the highest good as the end of human action; the rules that govern human action; the powers that command human action; and the ways and means by which the rules are practiced. While Locke lays out this conception of ethics in the Essay, not all aspects of his definition are explored in detail in that text. So, in order to get the full picture of how he understands each element of his description of ethics, we must often look to several different texts where they receive a fuller treatment. This means that Locke himself does not explain how these elements fit together leaving his overarching theory somewhat of a puzzle for future commentators to contemplate. But, by mining different texts in this way, we can piece together the details of an ethical theory that, while not always obviously coherent, presents a depth and complexity that, at minimum, confirms that this is a puzzle worth trying to solve.

2. The Good

a. Pleasure and Pain

The thread of moral discussion that weaves most consistently throughout the Essay is the subject of happiness. True happiness, on Locke’s account, is associated with the good, which in turn is associated with pleasure. Pleasure, in its turn, is taken by Locke to be the sole motive for human action. This means that the moral theory that is most directly endorsed in the Essay is hedonism.

On Locke’s view, ideas come to us by two means: sensation and reflection. This view is the cornerstone of his empiricism. According to this theory, there is no such thing as innate ideas or ideas that are inborn in the human mind. All ideas come to us by experience. Locke describes sensation as the “great source” of all our ideas and as wholly dependent on the contact between our sensory organs and the external world. The other source of ideas, reflection or “internal sense,” is dependent on the mind’s reflecting on its own operations, in particular the “satisfaction or uneasiness arising from any thought” (Essay, II.i.4). What’s more, Locke states that pleasure and pain are joined to almost all of our ideas both of sensation and of reflection (Essay, II.vii.2). This means that our mental content is organized, at least in one way, by ideas that are associated with pleasure and ideas that are associated with pain. That our ideas are associated with pains and pleasures seems compatible with our phenomenal experience: the contact between the sense organ of touch and a hot stove will result in an idea of the hot stove annexed by the idea of pain, or the act of remembering a romantic first kiss brings with it the idea of pleasure. And, Locke adds, it makes sense to join our ideas to the ideas of pleasure and pain because if our ideas were not joined with either pleasure of pain, we would have no reason to prefer the doing of one action over another, or the consideration of one idea over another. If this were our situation, we would have no reason to act—either physically or mentally (Essay, II.vii.3). That pleasure and pain are given this motivational role in action entails that Locke endorses hedonism: the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain are the sole motives for action.

Locke notes that among all the ideas that we receive by sensation and reflection, pleasure and pain are very important. And, he notes that the things that we describe as evil are no more than the things that are annexed to the idea of pain, and the things that we describe as good are no more than the things that are annexed to the idea of pleasure. In other words, the presence of good or evil is nothing other than the way a particular idea relates to us—either pleasurably or painfully. This means that on Locke’s view, good is just the category of things that tend to cause or increase pleasure or decrease pain in us, and evil is just the category of things that tend to cause or increase pain or decrease pleasure in us (Essay, II.xx.2). Now, we might think that, morally speaking, this way of defining good and evil gets Locke into trouble. Consider the following scenario. Smith enjoys breaking her promises. In other words, failing to honor her word brings her pleasure. According to the view just described, it seems that breaking promises, at least for Smith, is a good. For, if good and evil are defined as nothing more than pleasure and pain, it seems that if something gives Smith pleasure, it is impossible to deny that it is a good. This would be an unwelcome effect of Locke’s view, for it would indicate that his system leads directly to a kind of moral relativism. If promise breaking is pleasurable for Smith and promise keeping is pleasurable for her friend Jones and pleasure is the sign of the good, then it seems that the good is relative and there is no sense in which we can say that Jones is right about what is good and Smith is wrong. Locke blocks this kind of consequence for his view by introducing a distinction between “happiness” and “true happiness.” This indicates that while all things that bring us pleasure are linked to happiness, there is also a category of pleasure-bringing things that are linked to true happiness. It is the pursuit of the members of this special category of pleasurable things that is, for Locke, emblematic of the correct use of our intellectual powers.

b. Happiness

Locke is very clear—we all constantly desire happiness. All of our actions, on his view, are oriented towards securing happiness. Uneasiness, Locke’s technical term for being in a state of pain and desirous of some absent good, is the motive that moves us to act in the way that is expected to relieve the pain of desire and secure the state of happiness (Essay, II.xxi.36). But, while Locke equates pleasure with good, he is careful to distinguish the happiness that is acquired as a result of the satisfaction of any particular desire and the true happiness that is the result of the satisfaction of a particular kind of desire. Drawing this distinction allows Locke to hold that the pursuit of a certain sets of pleasures or goods is more worthy than the pursuit of others.

The pursuit of true happiness, according to Locke, is equated with “the highest perfection of intellectual nature” (Essay, II.xxi.51). And, indeed, Locke takes our pursuit of this true happiness to be the thing to which the vast majority of our efforts should be oriented. To do this, he says that we need to try to match our desires to “the true instrinsick good” that is really within things. Notice here that Locke is implying that there is distinction to be drawn between the “true intrinsic good” of a thing and, it seems, the good that we unreflectively take to be within a certain thing. The idea here is that attentively considering a particular thing will allow us to see its true value as opposed to the superficial value we assign to a thing based on our immediate reaction to it. We can think, for example, of a bitter tasting medicine. A face-value assessment of the medicine will lead us to evaluate that the thing is to be avoided. However, more information and contemplation of it will lead us to see that the true worth of the medicine is, in fact, high and so it should be evaluated as a good to be pursued. And, Locke states, if we contemplate a thing long enough, and see clearly the measure of its true worth; we can change our desire and uneasiness for it in proportion to that worth (Essay, II.xxi.53). But how are we to understand Locke’s suggestion that there is a true, intrinsic good in things? So far, all he has said about the good is that it is tracked by pleasure. We begin to get an answer to this question when Locke acknowledges the obvious fact that different people derive pleasure and pain from different things. While he reiterates that happiness is no more than the possession of those things that give the most pleasure and the absence of those things that cause the most pain, and that the objects in these two categories can vary widely among people, he adds the following provocative statement:

If therefore Men in this Life only have hope; if in this Life they can only enjoy, ’tis not strange, nor unreasonable, that they should seek their Happiness by avoiding all things, that disease them here, and by pursuing all that delight them; wherein it will be no wonder to find variety and difference. For if there be no Prospect beyond the Grave, the inference is certainly right, Let us eat and drink, let us enjoy what we delight in, for tomorrow we shall die [Isa, 22:13; I Cor. 15:32]. (Essay, II.xxi.55)

Here, Locke suggests that pursuing and avoiding the particular things that give us pleasure or pain would be a perfectly acceptable way to live were there “no prospect beyond the grave.” It seems that what Locke means is that if there were no judgment day, which is to say that if our actions were not ultimately judged by God, there would be no reason to do otherwise than to blindly follow our pleasures and flee our pains. Now, given this suggestion, the question, then, is how to distinguish between the things that are pleasurable but that will not help our case on judgment day, and those that will. Locke provides a clue for how to do such a thing when he says that the will is typically determined by those things that are judged to be good by the understanding. However, in many cases we use “wrong measures of good and evil” and end by judging unworthy things to be good. He who makes such a mistake errs because “[t]he eternal Law and Nature of things must not be alter’d to comply with his ill order’d choice” (Essay, II.xxi.56). In other words, there is an ordered way to choose which things to pursue—the things that are in accordance with the eternal law and nature of things—and an ill-ordered way, in accordance with our own palates. This indicates that Locke takes there to be a fixed law that determines which things are worthy of our pursuit, and which are not. This means that Locke takes there to be an important distinction between the good, understood as all objects that are connected to pleasure and the moral good, understood as objects connected to pleasure which are also in conformity with a law. Though the distinctions between good and moral good, and between evil and moral evil are not discussed in any great detail by Locke, he does states that moral good and evil is nothing other than the “Conformity or Disagreement of our voluntary Actions to some Law.” Locke states punishments and rewards are bestowed on us for our following or failure to follow this law by “the Will and Power of the Law-maker” (Essay, II.xxviii.5). So, Locke affirms that moral good and evil are closely tied to the observance or violation of some law, and that the lawmaker has the power to reward or punish those who adhere to or stray from the law.

3. The Law of Nature

a. Existence

In the Essay, the concepts of laws and lawmakers do not receive much treatment beyond Locke’s affirmation that God has decreed laws and that there are rewards and punishments associated with the respect or violation of these laws (Essay, I.iii.6; I.iii.12; II.xxi.70; II.xxviii.6). The two most important questions concerning the role of laws in a system of ethics remain unanswered in the Essay: (1) how do we determine the content of the law? This is the epistemological question. And (2) what kind of authority does the law have to obligate? This is the moral question. Locke spends much time considering these questions in a series of nine essays written some thirty years before the Essay, which are known under the collected title Essays on the Law of Nature (hereafter: Law).

The first essay in the series treats the question of whether there is a “rule of morals, or law of nature given to us.” The answer is unequivocally “yes” (Law, Essay I, page 109; hereafter: Law, I: 109). The reason for this positive answer, in short, is because God exists. Locke appeals to a kind of teleological argument to support the claim of God’s existence, saying that given the organization of the universe, including the organized way in which animal and vegetable bodies propagate, there must be a governing principle that is responsible for the patterns we see on earth. And, if we extend this principle to the existence of human life, Locke claims that it is reasonable to believe that there is a pattern or a law that governs behavior. This law is to be understood as moral good or virtue and, Locke states, it is the decree of God’s will and is discernable by “the light of nature.” Because the law tells us what is and is not in conformity with “rational nature,” it has the status of commanding or prohibiting certain behaviors (Law, I: 111; see also Essay, IV.xix.16). Because all human beings possess, by nature, the faculty of reason, all human beings, at least in principle, can discover the natural law.

Locke offers five reasons for thinking that such a natural law exists. He begins by noting that it is evident that there is some disagreement among people about the content of the law. However, far from thinking that such disagreement casts doubt on the existence of the law, he takes the presence of disagreement about the law as evidence that such a true and objective law exists. Disagreements about the content of the law confirm that everyone is in agreement about the fundamental character of the law—that there are things that are by their nature good or evil—but just disagree about how to interpret the law (Law, I: 115). The existence of the law is further reinforced by the fact that we often pass judgment on our own actions, by way of our conscience, leading to feelings of guilt or pride. Because it is not possible, according to Locke, to pronounce a judgment without the existence of a law, the act of conscience demonstrates that such a natural law exists. Third, again appealing to a kind of teleological argument, Locke states that we see that laws govern all manner of natural operations and that it makes sense that human beings would also be governed by laws that are in accordance with their nature (Law, I: 117). Fourth, Locke states that without the natural law, society would not be able to run the way that it does. He suggests that the force of civil law is grounded on the natural law. In other words, without the natural law, positive law would have no moral authority. Elsewhere, Locke underlines this point by saying that given that the law of nature is the eternal rule for all men, the rules made by legislators must conform to this law (The Two Treatises of Government, Treatise II, section 135, hereafter: Government, II.35). Finally, on Locke’s view, there would be no virtue or vice, no reward or punishment, no guilt, if there were no natural law (Law, I: 119). Without the natural law, there would be no bounds on human action. This means that we would be motivated only to do what seems pleasurable and there would be no sense in which anyone could be considered virtuous or vicious. The existence of the natural law, then, allows us to be sensitive to the fact that there are certain pleasures that are more in line with what is objectively right. Indeed, Locke also gestures towards, but does not elaborate on, this kind of thought in the Essay. He suggests that the studious man, who takes all his pleasures from reading and learning will eventually be unable to ignore his desires for food and drink. Likewise, the “Epicure,” whose only interest is in the sensory pleasures of food and drink, will eventually turn his attention to study when shame or the desire to “recommend himself to his Mistress” will raise his uneasiness for knowledge (Essay, II.xxi.43).

So, Locke has given us five reasons to accept the existence of the law of nature that grounds virtuous and vicious behavior. We turn now to how he thinks we come to know the content of the law.

b. Content

Locke suggests that there are two ways to determine the content of the law of nature: by the light of nature and by sense experience.

Locke is careful to note that by “light of nature” he does not mean something like an “inward light” that is “implanted in man” and like a compass constantly leads human beings towards virtue. Rather, this light is to be understood as a kind of metaphor that indicates that truth can be attained by each of us individually by nothing more than the exercise of reason and the intellectual faculties (Law, II: 123). Locke uses a comparison to precious metal mining to make this point clear. He acknowledges that some might say that his explanation of the discovery of the content of the law by the light of nature entails that everyone should always be in possession of the knowledge of this content. But, he notes, this is to take the light of nature as something that is stamped on the hearts on human beings, which is a mistake (see Law, III, 137-145). While the depths of the earth might contain veins of gold and silver, Locke says, this does not mean that everyone living on the stretch of land above those veins is rich (Law, II: 135). Work must be done to dig out the precious metals in order to benefit from their value. Similarly, proper use must be made of the faculties we have in order to benefit from the certainty provided by the light of nature. Locke notes that we can come to know the law of nature, in a way, by tradition, which is to say by the testimony and instruction of other people. But it is a mistake to follow the law for any reason other than that we recognize its universal binding force. This can only be done by our own intellectual investigation (Law, II: 129).

But what, exactly, is the light of nature? Locke acknowledges that it is difficult to answer this question—it is not something stamped on the heart or mind, nor is it something that is exclusively learned by tradition or testimony. The only option left for describing it, then, is that it is something acquired or experienced by sense experience or by reason. And, indeed, Locke suggests that when these two faculties, reason and sensation, work together, nothing can remain obscure to the mind. Sensation provides the mind with ideas and reason guides the faculty of sensation and arranges “together the images of things derived from sense-perception, thence forming others [ideas] and composing new ones” (Law, IV: 147). Locke emphasizes that reason ought to be taken to mean “the discursive faculty of the mind, which advances from things known to thinks unknown,” using as its foundation the data provided by sense experience (Law, IV: 149).

When directly addressing the question of how the combination of reason and sense experience allow us to know the content of the law of nature, Locke states that two important truths must be acknowledged because they are “presupposed in the knowledge of any and every law” (Law, IV: 151). First, we must understand that there is a lawmaker who decreed the law, and that the lawmaker is rightly obeyed as a superior power (a discussion of this point is also found in Government, I.81). Second, we must understand that the lawmaker wishes those to whom the law is decreed to follow the law. Let us take each of these in turn.

Sense experience allows us to know that a lawmaker exists. To demonstrate this, Locke appeals, once again, to a kind of teleological argument: by our senses we come to know the objects external world and, importantly, the regularities with which they move and change. We also see that we human beings are part of the movements and changes of the external world. Reason, then, contemplates these regularities and orders of change and motion and naturally comes to inquire about their origin. The conclusion of such an inquiry, states Locke, is that a powerful and wise creator exists. This conclusion follows from two observations: (1) that beasts and inanimate things cannot be the cause of the existence of human beings because they are clearly less perfect than human beings, and something less perfect cannot bring more perfect things into existence, and 2) that we ourselves cannot be the cause of our own existence because if we possessed the power to create ourselves, we would also have the power to give ourselves eternal life. Because it is obviously the case that we do not have eternal life, Locke concludes that we cannot be the origin of our own existence. So, Locke says, there must be a powerful agent, God, who is the origin of our existence (Law, IV: 153). The senses provide the data from the external world, and reason contemplates the data and concludes that a creator of the observed objects and phenomena must exist. Once the existence of a creator is determined, Locke thinks that we can also see that the creator has “a just and inevitable command over us and at His pleasure can raise us up or throw us down, and make us by the same commanding power happy or miserable” (Law, IV: 155). This commanding power, on Locke’s view, indicates that we are necessarily subject to the decrees of God’s will. (A similar line of discussion is found in Locke’s The Reasonableness of Christianity, 144–46.)

As for the second truth, that the lawmaker, God, wishes us to follow the laws decreed, Locke states that once we see that there is a creator of all things and that an order obtains among them, we see that the creator is both powerful and wise. It follows from these evident attributes that God would not create something without a purpose. Moreover, we notice that our minds and bodies seem well equipped for action, which suggests, “God intends man to do something.” And, the “something” that we are made to do, according to Locke, is the same purpose shared by all created things—the glorification of God (Law, IV: 157). In the case of rational beings, Locke states that given our nature, our function is to use sense experience and reason in order to discover, contemplate, and praise God’s creation; to create a society with other people and to work to maintain and preserve both oneself and the community. And this, in fact, is the content of the law of nature—to preserve one’s own being and to work to maintain and preserve the beings of the other people in our community. This injunction to preserve oneself and to preserve one’s neighbors is also endorsed and stressed throughout Locke’s discussions of political power and freedom (see Government, I.86, 88, 120; II.6, 25, 128).

c. Authority

Once we have knowledge of the content of the law of nature, we must determine from where it derives its authority. In other words, we must ask why we are bound to follow the law once we are aware of its content. Locke begins this discussion by reiterating that the law of nature “is the care and preservation of oneself.” Given this law, he states that virtue should not be understood as a duty but rather the “convenience” of human beings. In this sense, the good is nothing more than what is useful. Further, he adds, the observance of this law is not so much an obligation but rather “a privilege and an advantage, to which we are led by expediency” (Law, VI: 181). This indicates that Locke thinks that actions that are in conformity with the law are useful and practical. In other words, it is in our best interest to follow the law. While this characterization of why we in fact follow the law is compelling, there is nevertheless still an inquiry to be made into why we ought to follow the law.

Locke begins his treatment of this question by stating that no one can oblige us to do anything unless the one who obliges has some superior right and power over us. The obligation that is generated between such a superior power and those who are subject to it results in two kinds of duties: (1) the duty to pay obedience to the command of the superior power. Because our faculties are suited to discover the existence of the divine lawmaker, Locke takes it to be impossible to avoid this discovery, barring some damage or impediment to our faculties. This duty is ultimately grounded in God’s will as the force by which we were created (Law, VI: 183). (2) The duty to suffer punishment as a result of the failure to honor the first duty—obedience. Now, it might seem odd that it would be necessary to postulate that punishment results from the failure to respect a law the content of which is only that we must take care of ourselves. In other words, how could anyone express so little interest in taking care of himself or herself that the fear of punishment is needed to motivate the actions necessary for such care? It is worth quoting Locke’s answer in full:

[A] liability to punishment, which arises from a failure to pay dutiful obedience, so that those who refuse to be led by reason and to own that in the matter of morals and right conduct they are subject to a superior authority may recognize that they are constrained by force and punishment to be submissive to that authority and feel the strength of Him whose will they refuse to follow. And so the force of this obligation seems to be grounded in the authority of a lawmaker, so that power compels those who cannot be moved by warnings. (Law, VI: 183)

So, even though the existence, content, and authority of the law of nature are known in virtue of the faculties possessed by all rational creatures—sense experience and reason—Locke recognizes that there are people who “refuse to be led by reason.” Because these people do not see the binding force of the law by their faculties alone, they need some other impetus to motivate their behavior. But, Locke thinks very ill of those who are in need of this other impetus. He says the these features of the law of nature can be discovered by anyone who is diligent about directing their mind to them, and can be concealed from no one “unless he loves blindness and darkness and casts off nature in order that he may avoid his duty” (Law, VI: 189, see also Government, II.6).

d. Reconciling the Law with Happiness

The main lines of Locke’s natural law theory are as follows: there is a moral law that is (1) discoverable by the combined work of reason and sense experience, and (2) binding on human beings in virtue of being decreed by God. Now, in §1 above, we saw that Locke thinks that all human beings are naturally oriented to the pursuit of happiness. This is because we are motivated to pursue things if they promise pleasure and to avoid things if they promise pain. It has seemed to many commentators that these two discussions of moral principles are in tension with each other. On the view described in Law, Locke straightforwardly appeals to reason and our ability to understand the nature of God’s attributes to ground our obligation to follow the law of nature. In other words, what is lawful ought to be followed because God wills it and what is unlawful ought to be rejected because it is not willed by God. Because we can straightforwardly see that God is the law-giver and that we are by nature subordinate to Him, we ought to follow the law. By contrast, in the discussion of happiness and pleasure in the Essay, Locke explains that good and evil reduce to what is pleasurable and what is painful. While he does also indicate that the special categories of good and evil—moral good and moral evil—are no more than the conformity or disagreement between our actions and a law, he immediately adds that such conformity or disagreement is followed by rewards or punishments that flow from the lawmaker’s will. From this discussion, then, it is difficult to see whether Locke holds that it is the reward and punishment that binds human beings to act in accordance with the law, or if it is the fact that the law is willed by God.

One way to approach this problem is to suggest that Locke changed his mind. Because of the thirty-year gap between Law and the Essay, we might be tempted to think that the more rationalist picture, where the law and its authority are based on reason, was the young Locke’s view when he wrote Law. This view, the story would go, was replaced by Locke’s more considered and mature view, hedonism. But this approach must be resisted because both theories are present in early and late works. The role of pleasure and pain with respect to morality is present not only in the Essay, but is invoked in Law (passage quoted at the end of §2c), and many other various minor essays written in the years between Law and Essay (for example, ‘Morality’ (c.1677–78) in Political Essays, 267–69). Likewise, the role of the authority of God’s will is retained after Law, again evident in various minor essays (for example, ‘Virtue B’ (1681) in Political Essays, 287-88), Government II.6), Locke’s correspondence (for example, to James Tyrrell, 4 August 1690, Correspondence, Vol.4, letter n.1309) and even in the Essay itself (II.xxviii.8). An answer to how we might reconcile these two positions is suggested when we consider the texts where appeals to both theories are found side-by-side in certain passages.

In his essay Of Ethick in General (c. 1686–88) Locke affirms the hedonist view that happiness and misery consist only in pleasure and pain, and that we all naturally seek happiness. But in the very next paragraph, he states that there is an important difference between moral and natural good and evil—the pleasure and pain that are consequences of virtuous and vicious behavior are grounded in the divine will. Locke notes that drinking to excess leads to pain in the form of headache or nausea. This is an example of a natural evil. By contrast, transgressing a law would not have any painful consequences if the law were not decreed by a superior lawmaker. He adds that it is impossible to motivate the actions of rational agents without the promise of pain or pleasure (Of Ethick in General, §8). From these considerations, Locke suggests that the proper foundation of morality, a foundation that will entail an obligation to moral principles, needs two things. First, we need the proof of a law, which presupposes the existence of a lawmaker who is superior to those to whom the law is decreed. The lawmaker has the right to ordain the law and the power to reward and punish. Second, it must be shown that the content of the law is discoverable to humankind (Of Ethick in General, §12). In this text it seems that Locke suggests that both the force and authority of the divine decree and the promise of reward and punishment are necessary for the proper foundation of an obligating moral law.

A similar line of argument is found in the Essay. There, Locke asserts that in order to judge moral success or failure, we need a rule by which to measure and judge action. Further, each rule of this sort has an “enforcement of Good and Evil.” This is because, according to Locke, “where-ever we suppose a Law, suppose also some Reward or Punishment annexed to that Law” (Essay, II.xxviii.6). Locke states that some promise of pleasure or pain is necessary in order to determine the will to pursue or avoid certain actions. Indeed, he puts the point even more strongly, saying that it would be in vain for the intelligent being who decrees the rule of law to so decree without entailing reward or punishment for the obedient or the unfaithful (see also Government, II.7). It seems, then, that reason discovers the fact that a divine law exists and that it derives from the divine will and, as such, is binding. We might think, as Stephen Darwall suggests in The British Moralists and the Internal Ought, that if reason is that which discovers our obligation to the law, the role for reward and punishment is to motivate our obedience to the law. While this succeeds in making room for both the rationalist and hedonist strains in Locke’s view, some other texts seem to indicate that by reason alone we ought to be motivated to follow moral laws.

One striking instance of this kind of suggestion is found in the third book of the Essay where Locke boldly states that “Morality is capable of Demonstration” in the same way as mathematics (Essay, III.xi.16). He explains that once we understand the existence and nature of God as a supreme being who is infinite in power, goodness, and wisdom and on whom we depend, and our own nature “as understanding, rational Beings,” we should be able to see that these two things together provide the foundation of both our duty and the appropriate rules of action. On Locke’s view, with focused attention the measures of right and wrong will become as clear to us as the propositions of mathematics (Essay, IV.iii.18). He gives two examples of such certain moral principles to make the point: (1) “Where there is no Property, there is no Injustice” and (2) “No Government allows absolute Liberty.” He explains that property implies a right to something and injustice is the violation of a right to something. So, if we clearly see the intensional definition of each term, we see that (1) is necessarily true. Similarly, government indicates the establishment of a society based on certain rules, and absolute liberty is the freedom from any and all rules. Again, if we understand the definitions of the two terms in the proposition, it becomes obvious that (2) is necessarily true. And, Locke states, following this logic, 1 and 2 are as certain as the proposition that “a Triangle has three Angles equal to two right ones” (Essay, IV.iii.18). If moral principles have the same status as mathematical principles, it is difficult to see why we would need further inducement to use these principles to guide our behavior. While there is no clear answer to this question, Locke does provide a way to understand the role of reward and punishment in our obligation to moral principles despite the fact that it seems that they ought to obligate by reason alone.

Early in the Essay, over the course of giving arguments against the existence of innate ideas, Locke addresses the possibility of innate moral principles. He begins by saying that for any proposed moral rule human beings can, with good reason, demand justification. This precludes the possibility of innate moral principles because, if they were innate, they would be self-evident and thus would not be candidates for justification. Next, Locke notes that despite the fact that there are no innate moral principles, there are certain principles that are undeniable, for example, that “men should keep their Compacts.” However, when asked why people follow this rule, different answers are given. A “Hobbist” will say that it is because the public requires it, and the “Leviathan” will punish those who disobey the law. A “Heathen” philosopher will say that it is because following such a law is a virtue, which is the highest perfection for human beings. But a Christian philosopher, the category to which Locke belongs, will say that it is because “God, who has the Power of eternal Life and Death, requires it of us” (Essay, I.iii.5). Locke builds on this statement in the following section when he notes that while the existence of God and the truth of our obedience to Him is made manifest by the light of reason, it is possible that there are people who accept the truth of moral principles, and follow them, without knowing or accepting the “true ground of Morality; which can only be the Will and Law of God” (Essay, I.iii.6). Here Locke is suggesting that we can accept a true moral law as binding and follow it as such, but for the wrong reasons. This means that while the Hobbist, the Heathen, and the Christian might all take the same law of keeping one’s compacts to be obligating, only the Christian does it for the right reason—that God’s will requires our obedience to that law. Indeed, Locke states that if we receive truths by revelation they too must be subject to reason, for to follow truths based on revelation alone is insufficient (see Essay, IV.xviii).

Now, to determine the role of pain and pleasure in this story, we turn to Locke’s discussion of the role of pain and pleasure in general. He says that God has joined pains and pleasures to our interaction with many things in our environment in order to alert us to things that are harmful or helpful to the preservation of our bodies (Essay, II.vii.4). But, beyond this, Locke notes that there is another reason that God has joined pleasure and pain to almost all our thoughts and sensations: so that we experience imperfections and dissatisfactions. He states that the kinds of pleasures that we experience in connection to finite things are ephemeral and not representative of complete happiness. This dissatisfaction coupled with the natural drive to obtain happiness opens the possibility of our being led to seek our pleasure in God, where we anticipate a more stable and, perhaps, permanent happiness. Appreciating this reason why pleasure and pain are annexed to most of our ideas will, according to Locke, lead the way to the ultimate aim of the enquiry in human understanding—the knowledge and veneration of God (Essay, II.vii.5–6). So, Locke seems to be suggesting here that pain and pleasure prompt us to find out about God, in whom complete and eternal happiness is possible. This search, in turn, leads us to knowledge of God, which will include the knowledge that He ought to be obeyed in virtue of His decrees alone. Pleasure and pain, reward and punishment, on this interpretation, are the means by which we are led to know God’s nature, which, once known, motivates obedience to His laws. This mechanism supports Locke’s claim that real happiness is to be found in the perfection of our intellectual nature—in embarking on the search for knowledge of God, we embark on the intellectual journey that will lead to the kind of knowledge that brings permanent pleasure. This at least suggests that the knowledge of God has the happy double-effect of leading to both more stable happiness and the understanding that God is to be obeyed in virtue of His divine will alone.

But given that all human beings experience pain and pleasure, Locke needs to explain how it is that certain people are virtuous, having followed the experience of dissatisfaction to arrive at the knowledge of God, and other people are vicious, who seek pleasure and avoid pain for no reason other than their own hedonic sensations.

4. Power, Freedom, and Suspending Desire

a. Passive and Active Powers

In any discussion of ethics, it is important not only to determine what, exactly, counts as virtuous and vicious behavior, but also the extent to which we are in control of our actions. This is important because we want to be able to adequately connect behavior to agents in order to attribute praise or blame, reward or punishment to an agent, we need to be able to see the way in which she is the causal source of her own actions. Locke addresses this issue in one of the longest chapters of the Essay—“Of Power.” In this chapter, Locke describes how he understands the nature of power, the human will, freedom and its connection to happiness, and, finally, the reasons why many (or even most) people do not exercise their freedom in the right kind of way and are unhappy as a result. It is worth noting here that this chapter of the Essay underwent major revisions throughout the five editions of the Essay and in particular between the first and second edition. The present discussion is based on the fourth edition of the Essay (but see the “References and Further Reading” below for articles that discuss the relevance of the changes throughout all five editions).

Locke states that we come to have the idea of “power” by observing the fact that things change over time. Finite objects are changed as a result of interactions with other finite objects (for example fire melts gold) and we notice that our own ideas change either as a result of external stimulus (for example the noise of a jackhammer interrupts the contemplation of a logic problem) or as a result of our own desires (for example hunger interrupts the contemplation of a logic problem). The idea of power always includes some kind of relation to action or change. The passive side of power entails the ability to be changed and the active side of power entails the ability to make change. Our observation of almost all sensible things furnishes us with the idea of passive power. This is because sensible things appear to be in almost constant flux—they are changed by their interaction with other sensible things, with heat, cold, rain, and time. And, Locke adds, such observations give us no fewer instances of the idea of active power, for “whatever Change is observed, the Mind must collect a Power somewhere, able to make that Change” (Essay, II.xxi.4). However, when it comes to active powers, Locke states that the clearest and most distinct idea of active power comes to us from the observation of the operations of our own minds. He elaborates by stating that there are two kinds of activities with which we are familiar: thinking and motion. When we consider body in general, Locke states that it is obvious that we receive no idea of thinking, which only comes from a contemplation of the operations of our own minds. But neither does body provide the idea of the beginning of motion, only of the continuation or transfer of motion. The idea of the beginning of motion, which is the idea associated with the active power of motion, only comes to us when we reflect “on what passes in our selves, where we find by Experience, that barely by willing it, barely by a thought of the Mind, we can move the parts of our Bodies, which were before at rest” (Essay, II.xxi.4). So, it seems, the operation of our minds, in particular the connection between one kind of thought, willing, and a change in either the content of our minds or the orientation of our bodies, provides us with the idea of an active power.

b. The Will

The power to stop, start, or continue an action of the mind or of the body is what Locke calls the will. When the power of the will is exercised, a volition (or willing) occurs. Any action (or forbearance of action) that follows volition is considered voluntary. The power of the will is coupled with the power of the understanding. This latter power is defined as the power of perceiving ideas and their agreement or disagreement with one another. The understanding, then, provides ideas to the mind and the will, depending on the content of these ideas, prefers certain courses of action to others. Locke explains that the will directs action according to its preference—and here we must understand “preference” in the most general sense of inclination, partiality, or taste. In short, the will is attracted to actions that promise the procurement of pleasing things and/or the distancing from displeasing things. The technical term that Locke uses to describe that which determines the will is uneasiness. He elaborates, stating that the reason why any action is continued is “the present satisfaction in it” and the reason why any action is taken to move to a new state is dissatisfaction (Essay, II.xxi.29). Indeed, Locke affirms that uneasiness, at bottom, is really no more than desire, where the mind is disturbed by a “want of some absent good” (Essay, II.xxi.31). So, any pain or discomfort of the mind or body is a motive for the will to command a change of state so as to move from unease to ease. Locke notes that it is a common fact of life that we often experience multiple uneasinesses at one time, all pressing on us and demanding relief. But, he says, when we ask the question of what determines the will at any one moment, the answer is the most pressing uneasiness (Essay, II.xxi.31). Imagine a situation where you are simultaneously experiencing discomfort as a result of hunger and the anxiety of being under-prepared for tomorrow’s philosophy exam. On Locke’s view the most intense or the most pressing of these uneasinesses will determine your will to command the action that will relieve it. This means that no matter how much you want to stay at the library to study, if hunger comes to be the more pressing than the desire to pass the exam, hunger will determine the will to act, commanding the action that will result in the procurement of food.

While Locke states that the most pressing uneasiness determines the will, he adds that it does so “for the most part, but not always.” This is because he takes the mind to have the power to “suspend the execution and satisfaction of any of its desires” (Essay, II.xxi.47). While a desire is suspended, Locke says, our mind, being temporarily freed from the discomfort of the want for the thing desired, has the opportunity to consider the relative worth of that thing. The idea here is that with appropriate deliberation about the value of the desired thing we will come to see which things are really worth pursuing and which are better left alone. And, Locke states, the conclusion at which we arrive after this intellectual endeavor of consideration and examination will indicate what, exactly, we take to be part of our happiness. And, in turn, by a mechanism that Locke does not describe in any detail, our uneasiness and desire for that thing will change to reflect whether we concluded that the thing does, indeed, play a role in our happiness or not (Essay, II.xxi.56). The problem is that there is no clear explanation for how, exactly, the power to suspend works. Despite this, Locke nowhere indicates that suspension is an action of the mind that is determined by anything other than volition of the will. We know that Locke takes all acts of the will to be determined by uneasiness. So, suspending our desires must be the result of uneasiness for something. Investigating how Locke understands human freedom and judgment will allow us to see what, exactly, we are uneasy for when we are determined to suspend our desires.

c. Freedom

When the nature of the human will is under discussion, we often want to know the extent of this faculty’s freedom. The reason why this question is important is because we want to see how autonomously the will can act. Typically, the question takes the form of: is the will free? Locke unequivocally denies that the will is free, implying, in fact, that it is a category mistake to ask the question at all. This is because, on his view, both the will and freedom are powers of agents, and it is a mistake to think that one power (the will) can have as a property a second power (freedom) (Essay, II.xxi.20). Instead, Locke thinks that the right question to pose is whether the agent is free. He defines freedom in the following way:

[T]he Idea of Liberty, is the Idea of a Power in any Agent to do or forbear any particular Action, according to the determination or thought of the mind, whereby either of them is preferr’d to the other; where either of them is not in the Power of the Agent to be produced by him according to his Volition here he is not a Liberty, that Agent is under Necessity. (Essay, II.xxi.8)

So, Locke considers that an agent is free in acting when her action is connected to her volition in the right kind of way. That is, when her action (or forbearance of action) follows from her volition, she is free. And, her volition is determined by the “thought of the mind” that indicates which action is preferred.

Notice here that Locke takes an agent to be free in acting when she acts according to her preference—this means that her actions are determined by her preference. This plainly shows that Locke does not endorse a kind of freedom of indifference, according to which the will can choose to command an action other than the thing most preferred at a given moment. This is the kind of freedom most often associated with indeterminism. Freedom, then, for Locke, is no more than the ability to execute the action that is taken to result in the most pleasure at a given moment. The problem with this way of defining freedom is that it seems unable to account for the kinds of actions we typically take to be emblematic of virtuous or vicious behavior. This is because we tend to think that the power of freedom is a power that allows us to avoid vicious actions, perhaps especially those that are pleasurable, in order to pursue a righteous path instead. For instance, on the traditional Christian picture, when we wonder about why God would allow Adam to sin, the response given is that Adam was created as a free being. While God could have created beings that, like automata, unfailingly followed the good and the true, He saw that it was all things considered better to create beings that were free to choose their own actions. This decision was made despite the fact that God foresaw the sinful use to which this freedom would be put. This traditional view explains Adam’s sin in the following way: Adam knew that it was God’s commandment that he was not to eat of the tree of knowledge. Adam also knew that following God’s commandment was the right thing to do. So, in the moment where he was tempted to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge, he knew it was the wrong thing to do, but did it anyway. This is because, the story goes, and in that moment he was free to decide whether to follow the commandment or to give in to temptation. Of his own free choice, Adam decided to follow temptation. This means that in the moment of original sin, both following God’s commandment and eating the fruit were live options for Adam, and he chose the fruit of his own agency.

Now, on Locke’s system, a different explanation obtains. Given his definition of freedom, it is difficult, at least prima facie, to see how Adam could be blamed for choosing the fruit over the commandment. For, according to Locke, an agent acts freely when her actions are determined by her volitions. So, if Adam’s greatest uneasiness was for the fruit, and the act of eating the fruit was the result of his will commanding such action based on his preference, then he acted freely. But, on this understanding of freedom, it is difficult to see how, exactly, Adam can be morally blamed for eating the fruit. The question now becomes: is Adam to be blamed for anticipating more pleasure from the consumption of the fruit than from following God’s command? In other words, was it possible for Adam to alter the intensity of his desire for the fruit? It seems that on Locke’s view, the answer must be connected to one of the powers he takes human beings to possess—the power to suspend desires. And, in certain passages of the Essay, Locke implies that suspending desires and freedom are linked, suggesting that while agents are acting freely whenever their volitions and actions are linked in the right kind of way, there is, perhaps, a proper use of the power to act freely.

d. Judgment

Locke asserts that the “highest perfection of intellectual nature” is the “pursuit of true and solid happiness.” He adds that taking care not to mistake imaginary happiness for real happiness is “the necessary foundation of our liberty.” And, he writes that the more closely we are focused on the pursuit of true happiness, which is our greatest good, the less our wills are determined to command actions to pursue lesser goods that are not representative of the true good (Essay, II.xxi.51). In other words, the more we are determined by true happiness, the more we will to suspend our desires for lesser things. This suggests that Locke takes there to be a right way to use our power of freedom. Locke indicates that there are instances where it is impossible to resist a particular desire—when a violent passion strikes, for instance. He also states, however, that aside from these kinds of violent passions, we are always able to suspend our desire for any thing in order to give ourselves the time and the emotional distance from the thing desired in which to consider the worth of thing relative to our general goal: true happiness. True happiness, or real bliss, on Locke’s view, is to be found in the pursuit of things that are true intrinsic goods, which promise “exquisite and endless Happiness” in the next life (Essay, II.xxi.70). In other words, true good is something like the Beatific Vision.

Now, Locke admits that it is a common experience to be carried by our wills towards things that we know do not play a role in our overall and true happiness. However, while he allows that the pursuit of things that promise pleasure, even if only a temporary pleasure, represents the action of a free agent, he also says that it is possible for us to be “at Liberty in respect of willing” when we choose “a remote Good as an end to be pursued” (Essay, II.xxi.56). The central thing to note here is that Locke is drawing a distinction between immediate and remote goods. The difference between these two kinds of goods is temporal. For instance, acting to obtain the pleasure of intoxication is to pursue an immediate good while acting to obtain the pleasure of health is to pursue a remote good. So, we can suppose here that Locke is suggesting that forgoing immediate goods and privileging remote goods is characteristic of the right use of liberty (but see Rickless for an alternative interpretation). If this is so, it is certainly not a difficult suggestion to accept. Indeed, it is fairly straightforwardly clear that many immediate pleasures do not, in the end, contribute to overall and long-lasting happiness.

The question now, and it is a question that Locke himself poses, is “How Men come often to prefer the worse to the better; and to chase that, which, by their own Confession, has made them miserable” (Essay, II.xxi.56). Locke gives two answers. First, bad luck can account for people not pursuing their true happiness. For instance, someone who is afflicted with an illness, injury, or tragedy is consumed by her pain and is thus unable to adequately focus on remote pleasures. Quoting Locke’s second answer “Other uneasinesses arise from our desire of absent good; which desires always bear proportion to, and depend on the judgment we make, and the relish we have of any absent good; in both which we are apt to be variously misled, and that by our own fault” (Essay, II.xxi.57).

Here Locke states that our own faulty judgment is to blame for our preferring the worse to the better. This is because, on his view, the uneasiness we have for any given object is directly proportional to the judgments we make about the merit of the things to which we are attracted. So, if we are most uneasy for immediate pleasures, it is our own fault because we have judged these things to be best for us. In this way, Locke makes room in his system for praiseworthiness and blameworthiness with respect to our desires: absent illness, injury, or tragedy, we ourselves are responsible for endorsing, through judgment, our uneasinesses. He continues, stating that the major reason why we often misjudge the value of things for our true happiness is that our current state fools us into thinking that we are, in fact, truly happy. Because it is difficult for us to consider the state of true, eternal happiness, we tend to think that in those moments when we enjoy pleasure and feel no uneasiness, we are truly happy. But such thoughts are mistaken on his view. Indeed, as Locke says, the greatest reason why so few people are moved to pursue the greatest, remote good is that most people are convinced that they can be truly happy without it.

The cause of our mistaken judgments is the fact that it is very difficult for us to compare present and immediate pleasures and pains with future or remote pleasures and pains. In fact, Locke likens this difficulty to the trouble we typically experience in correctly estimating the size of distant objects. When objects are close to us, it is easy to determine their size. When they are far away, it is much more difficult. Likewise, he says, for pleasures and pains. He notes that if every sip of alcohol were accompanied by headache and nausea, no one would ever drink. But, “the fallacy of a little difference in time” provides the space for us to mistakenly judge that the alcohol contributes to our true happiness (Essay, II.xxi.63). We experience this difficulty of judging remote pleasures and pains due to the “weak and narrow Constitution of our Minds” (Essay, II.xxi.64). The condition of our minds makes it easy for us to think that there could be no greater good than the relief of being unburdened of a present pain. In order to correct this problem and convince a man to judge that his greatest good is to be found in a remote thing, Locke says that all we must do is convince him that “Virtue and Religion are necessary to his Happiness” (Essay, II.xxi.60). Locke explains that a “due consideration will do it in most cases; and practice, application, and custom in most” (Essay, II.xxi.69). The suggestion is that contemplation and deliberation alone may be sufficient to correct our problem of considering all immediate pleasures and pains to be greater than any future ones. And, if that does not work, practice and habit can also correct this problem. By practice and exposure, we can, according to Locke, change the agreeableness or disagreeableness of things. It seems, then, that the power to suspend desire must be the power to reject immediate pleasures in favor of the pursuit of remote or future pleasures. However, it seems that in order to suspend in this way, we must already have judged that these immediate pleasures are not representative of the true good. For, without this kind of prior judgment, it seems that we would not be in a position to suspend in the way that is required. This is because absent the prior judgment, there would be no reason for the uneasiness we felt for the perceived good to not determine the will. The question to resolve now is how to get ourselves into a position where we are uneasy for the remote, true good and can suspend our desires for immediate pleasures. In other words, we must determine how we can come to seriously judge immediate pleasures to not have a part in our true happiness.

5. Living the Moral Life

In order to behave in a way that will lead us to the greatest and truest happiness, we must come to judge the remote and future good, the “unspeakable,” “infinite,” and “eternal” joys of heaven to be our greatest and thus most pleasurable good (Essay, II.xxi.37–38). But, on Locke’s view, our actions are always determined by the thing we are most uneasy about at any given moment. So, it seems, we need to cultivate the uneasiness for the infinite joys of heaven. But if, as Locke suggests, the human condition is such that our minds, in their weak and narrow states, judge immediate pleasures to be representative of the greatest good, it is difficult to see how, exactly, we can circumvent this weakened state in order to suspend our more terrestrial desires and thus have the space to correctly judge which things will lead to our true happiness. While in the Essay Locke does not say as much as we might like on this topic, elsewhere in his writings we can get a sense for how he might respond to this question.

In 1684, Locke was asked by his friend Edward Clarke, for advice about raising and educating his children. In 1693, Locke’s musings on this topic were published as Some Thoughts Concerning Education (hereafter: Education). This text provides insight into the importance that Locke places on the connection between the pursuit of true happiness and early childhood education in general. Locke begins his discussion by noting that happiness is crucially dependent on the existence of both a sound mind and a sound body. He adds that it sometimes happens that by a great stroke of luck, someone is born whose constitution is so strong that they do not need help from others to direct their minds towards the things that will make them happy. But this is an extraordinarily rare occurrence. Indeed, Locke notes: “I think I may say, that, of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education” (Education, §1). It is the education we receive as young children, on Locke’s view, that determines how adept we are at targeting the right objects in order to secure our happiness. He observes that the minds of young children are easily distracted by all kinds of sensory stimuli and notes that the first step to developing a mind that is focused on the right kind of things is to ensure that the body is healthy. Indeed, the objective in physical health is to get the body in the perfect state to be able to obey and carry out the mind’s commands. The more difficult part of this equation is training the mind to “be disposed to consent to nothing, but what may be suitable to the dignity and excellency of a rational creature” (Education, §31). And Locke goes further still, stating that the foundation of all virtue is to be placed in the ability of a human being to “deny himself his own desires, cross his own inclinations, and purely follow what reason directs as best, though the appetite lean the other way” (Education, §33). The way to do this, he says, is to resist immediately present pleasures and pains and to wait to act until reason has determined the value of the desirable things in one’s environment.

Locke states that we must recognize the difference between “natural wants” and “wants of fancy.” The former are the kinds of desires that must be obeyed and that no amount of reasoning will allow us to give up. The latter, however, are created. Locke states that parents and teachers must ensure that children develop the habit of resisting any kind of created fancy, thus keeping the mind free from desires for things that do not lead to true happiness (Education, §107). If parents and teachers are successful in blocking the development of “wants of fancy,” Locke thinks that the children who benefit from this success will become adults who will be “allowed greater liberty” because they will be more closely connected to the dictates of reason and not the dictates of passion (Education, §108). So, in order to live the moral life and listen to reason over passions, it seems that we need to have had the benefit of conscientious care-givers in our infancy and youth (see also Government, II.63). This raises the difficulty of how to connect an individual’s moral successes or failures with the individual herself. For, if she had the bad moral luck of unthinking or careless parents and teachers, it seems difficult to see how she could be blamed for failing to follow a virtuous path.

One way of approaching this difficulty is to recall that Locke takes the content of law of nature, the moral law decreed by God, to be the preservation both of ourselves and of the other people in our communities in order to glorify God (Law, IV). The dictate to help to preserve the other people in our community shifts some of the moral burden from the individual onto the community. This means that it is every individual’s responsibility to do all they can, all things considered, to preserve themselves and to ensure, to the best of their ability, that the children in their communities are raised to avoid developing wants of fancy. In this way, children will develop the habit of suspending their desires for terrestrial pleasures and focusing their efforts on attaining the true happiness that results from acting to secure remote goods.

6. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

- An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Edited by Peter H. Nidditch. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975.

- This is the critical edition of Locke’s Essay. The body of the text is based on the fourth edition of the Essay and all the changes from the first edition through the fifth (1689, 1694, 1695, 1700, 1706) are indicated in the footnotes. The text also includes a comprehensive forward by Nidditch. Note that Locke’s orthography, grammar, and style are often quite different from the way that academic English is written today. In the citations from this text in particular, all emphases, capitalization, and odd spelling are original to Locke.

- Essays on the Laws of Nature. Edited and translated by W. von Leyden. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1954.

- This edition includes both the original Latin and the English translation of the essays. It also includes Locke’s valedictory speech as censor of moral philosophy at Christ Church and some other shorter pieces of writing. Von Leyden’s introduction provides a very detailed discussion of the sources of Locke’s arguments in these essays, the arguments themselves, and the relations these arguments bear to other of Locke’s writings. It is worth noting here that on von Leyden’s interpretation, it is not possible to render Locke’s discussion of natural law consistent with his endorsement of a hedonistic motivational system in later works.

- Political Essays. Edited by Mark Goldie. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- This collection includes major writings on politics and government, including Essays on the Laws of Nature, Of Ethick in General, and An Essay on Toleration, in addition to many other minor essays.

- The Correspondence of John Locke, in Eight Volumes. Edited by E.S. De Beer. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976–89.

- A complete database of Locke’s correspondence including notes about his correspondents, notes about events and proper names mentioned in letters, as well as signposts for what was going on in Locke’s life at the time he was writing. The first volume of the collection includes an exhaustive introduction to Locke’s life, work, and contacts in the academic and social world; an explanation of how Locke’s letters were preserved; a discussion of previous publications of Locke’s correspondence and how they relate to this collection; and information about transcription practices, including details about editorial grammar decision and dating of the letters.

- The Works of John Locke, in Nine Volumes, 12th edition. London: Rivington, 1824.

- This collection includes most of Locke’s longer texts, some shorter texts and a selection of letters. Among other things, the collection contains: Essay (vols.1 and 2), his correspondence with Stillingfleet (vol.3), Two Treatises of Government (vol.4), Letters on Toleration (vol.5), The Reasonableness of Christianity (vol.6), notes on St. Paul’s Epistles (vol.7), Some Thoughts Concerning Education and A Discourse of Miracles (vol.8), and a selection of letters (vol.9).

b. Secondary Sources: Books

- Aaron, Richard I. John Locke. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- This is a comprehensive study of Locke’s life and works and includes fifteen very nice pages on Locke’s moral philosophy. Importantly, Aaron concludes that Locke fails to provide his readers with a science of morals and, in fact, that Locke’s disparate comments about ethics and moral principles cannot be reconciled.

- Colman, John. John Locke’s Moral Philosophy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983.

- In this study, Colman addresses the major themes and problems of Locke’s moral theory including the connection between law and obligation, and the connection between moral principles and demonstrability.

- Darwall, Stephen. The British Moralists and the Internal ‘Ought’: 1640–1740. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- This is a deep and broad study of moral philosophy from the mid 17th to the mid 18th century. Locke is one among several central figures under discussion. The reader greatly benefits from Darwall’s careful discussions of the theoretical connections between Locke and his contemporaries and his influences on the topics of natural law, autonomy, motivation, duty, and freedom.

- Lolordo, Antonia. Locke’s Moral Man. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- In this study, Lolordo draws on different parts of the Essay in order to see Locke’s theory of agency. She argues in favor of the interpretation according to which there are two senses of freedom in Locke’s view, one of which is properly used to attain the goal proper to a moral agent. Of particular interest is her discussion that links Locke’s comments about personal identity to moral agency and her claim that, for Locke, metaphysics is unnecessary for ethics.

- Mabbot, J.D. John Locke. London: Macmillan Press, 1973.

- This is a study of Locke’s philosophical system that focuses on knowledge acquisition, logic and language, ethics and theology, and political theory. In his discussion of ethics and theology, Mabbot traces Locke’s discussions of moral principles, their demonstrability, and their binding force through The Two Treatises of Government, The Essays on the Laws of Nature, and An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

- Schouls, Peter A. Reasoned Freedom: John Locke and Enlightenment. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992.

- This is a defense of the view that Locke was a great influence on enlightenment thought, in particular in the domains of reason and freedom. Schouls also points out what he takes to be many inconsistencies across and sometimes within Locke’s texts.

- Yaffe, Gideon. Liberty Worth the Name: Locke on Free Agency. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- This is a book-length study of Locke’s view of human freedom. The content includes careful analysis of the chapter ‘Of Power’ of the Essay in addition to comments about how this chapter is connected to Locke’s discussion of personal identity. Yaffe defends an interpretation according to which Locke’s view contains two definitions of freedom, only one of which is “worth the name”—the kind of freedom that allows the pursuit of true good.

c. Secondary Sources: Articles

- Chappell, Vere. “Locke on the Intellectual Basis of Sin.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 32 (1994): 197–207.

- Chappell, Vere. “Locke on the Liberty of the Will.” In Locke’s Philosophy: Content and Context. Edited by G.A.J. Rogers, 101–21. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Chappell, Vere. “Power in Locke’s Essay.” In The Cambridge Companion to Locke’s “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.” Edited by Lex Newman, 130–56. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- In these articles, Chappell advances the interpretation that changes made in the fifth edition of the Essay indicate that Locke changed his view about human freedom.

- Darwall, Stephen. “The Foundations of Morality,” In The Cambridge Companion to Early Modern Philosophy. Edited by Donald Rutherford, 221–49.

- This paper canvasses the main themes explored by and influences on early modern moral theories, including Locke’s.

- Glauser, Richard. “Thinking and Willing in Locke’s Theory of Human Freedom,” Dialogue 42 (2003): 695–724.

- Glauser argues that Locke’s view remains consistent across the changes made in the various editions of the Essay.

- Magri, Tito. “Locke, Suspension of Desire, and the Remote Good,” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 8 (2000): 55–70.

- Magri argues that Locke’s view changes over the course of the different editions of the Essay, in particular that he moves from having an “internalist” view of motivation to having an “externalist” view of motivation. Magri casts doubt on the consistency of Locke’s position.

- Mathewson, Mark D. “John Locke and the Problems of Moral Knowledge,” Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 87 (2006): 509–26.

- Mathewson argues that Locke’s comments about the nature of moral ideas leads to moral subjectivity and relativism.

- Rickless, Samuel. “Locke on Active Power, Freedom, and Moral Agency,” Locke Studies 13 (2013): 31–51.

- Rickless, Samuel. “Locke on the Freedom to Will.” Locke Newsletter 31 (2000): 43–68.

- In these papers, Rickless argues that Locke holds one and only one definition of freedom: the ability to act according to our volitions. According to Rickless, Locke holds the same definition of freedom as Hobbes. The 2013 paper is a direct argument against the interpretation advanced by Lolordo in Locke’s Moral Man.

- Schneewind, J.B. “Locke’s Moral Philosophy,” The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Edited by Vere Chappell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Schneewind is one commentator who thinks that Locke’s moral philosophy ends up in a contradiction between the natural law view and hedonism.

- Walsh, Julie. “Locke and the Power to Suspend Desire,” Locke Studies, 14 (2014).

- Walsh argues that Locke’s view remains consistent and coherent across the various editions of the Essay and emphasizes the role played by suspension and judgment in attaining true happiness.

Author Information

Julie Walsh

Email: julie.walsh@wellesley.edu

Wellesley College

U. S. A.