Socialism

Socialism is both an economic system and an ideology (in the non-pejorative sense of that term). A socialist economy features social rather than private ownership of the means of production. It also typically organizes economic activity through planning rather than market forces, and gears production towards needs satisfaction rather than profit accumulation. Socialist ideology asserts the moral and economic superiority of an economy with these features, especially as compared with capitalism. More specifically, socialists typically argue that capitalism undermines democracy, facilitates exploitation, distributes opportunities and resources unfairly, and vitiates community, stunting self-realization and human development. Socialism, by democratizing, humanizing, and rationalizing economic relations, largely eliminates these problems.

Socialist ideology thus has both critical and constructive aspects. Critically, it provides an account of what’s wrong with capitalism; constructively, it provides a theory of how to transcend capitalism’s flaws, namely, by transcending capitalism itself, replacing capitalism’s central features (private property, markets, profits) with socialist alternatives (at a minimum social property, but typically planning and production for use as well).

How, precisely, socialist concepts like social ownership and planning should be realized in practice is a matter of dispute among socialists. One major split concerns the proper role of markets in a socialist economy. Some socialists argue that extensive reliance on markets is perfectly compatible with core socialist values. Others disagree, arguing that to be a socialist is (among other things) to reject the ‘anarchy of the market’ in favor of a planned economy. But what form of planning should socialists advocate? This is a second major area of dispute, with some socialists endorsing central planning and others proposing a radically decentralized, participatory alternative.

This article explores all of these themes. It starts with definitions, then presents normative arguments for preferring socialism to capitalism, and concludes by discussing three broad socialist institutional proposals: central planning, participatory planning, and market socialism.

Two limitations should be noted at the outset. The article focuses on moral and political-philosophical issues rather than purely economic ones, discussing the latter only briefly. Second, little is said here about socialism’s rich and complicated history. The article emphasizes the philosophical content of socialist ideas rather than their historical development or political instantiation.

Table of Contents

- Socialism and Capitalism: Basic Institutional Contrasts

- Socialism vs. Communism in Marxist Thought

- Why Socialism? Economic Considerations

- Why Socialism? Democracy

- Why Socialism? Exploitation

- Why Socialism? Freedom and Human Development

- Why Socialism? Community and Equality

- Institutional Models of Socialism for the 21st Century

- References and Further Reading

1. Socialism and Capitalism: Basic Institutional Contrasts

Considered as an economic system, socialism is best understood in contrast with capitalism.

Capitalism designates an economic system with all of the following features:

- The means of production are, for the most part, privately owned;

- People own their labor power, and are legally free to sell it to (or withhold it from) others;

- Production is generally oriented towards profit rather than use: firms produce not in the first instance to satisfy human needs, but rather to make money; and

- Markets play a major role in allocating inputs to commodity production and determining the amount and direction of investment.

An economic system is socialist only if it rejects feature 1, private ownership of the means of production in favor of public or social ownership. But must an economic system reject any of features 2-4 to count as socialist, or is rejection of private property sufficient as well as necessary? Here, socialists disagree. Some, often called “market socialists”, hold that socialism is compatible, in principle, with wage labor, profit-seeking firms, and extensive use of markets to organize and coordinate production and investment. Others, sometimes called “orthodox” or “classical” socialists, contend that an economic system with these features is scarcely distinguishable from capitalism; true socialism, on this view, requires not merely social ownership of the means of production but also planned production for use, as opposed to “anarchic”, market-driven production for profit.

This section explores the core socialist commitment to social ownership of the means of production. Other important aspects of socialism—for instance, its stance towards markets and planning—are discussed in later sections (especially section 8).

a. Ownership: Some Preliminaries

Consider a society’s instruments of production, its land, buildings, factories, tools, and machinery; consider also its raw materials, its oil and timber and minerals and so on. Together, these instruments and these materials comprise society’s means of production. To whom should these means of production belong: to society as a whole, or to private individuals or groups of individuals? This is the central question dividing capitalists and socialists, with capitalists advocating extensive rights of private ownership of the means of production and socialists advocating extensive social or public ownership of these means.

Notice that the capitalist/socialist dispute does not concern the desirability of private property in items unrelated to production. The issue between socialists and capitalists is not whether individuals should be able to own “personal property” (for example, toothbrushes, houses, clothing, and other articles of everyday use) but whether they should be able to own “productive property” (for example, stores, factories, raw materials, and other productive assets).

But what does it mean to own something? Standardly, to own something is to enjoy a bundle of legally enforceable rights and powers over that thing. These rights and powers typically include the right to use, to control, to transfer, to alter (at the limit, even to destroy), and to generate income from the thing owned, as well as the right to exclude non-owners from interacting with the owned thing in these ways. Because these rights admit of gradations, so too does ownership, which is scalar—a matter of degree—rather than dichotomous. In general, the wider one’s rights of use, control, and so on over an object, the fewer restrictions one faces in exercising these various rights, and the wider one’s ownership rights over that object. Ownership, notice, may be narrowed and restricted without ceasing to be ownership. Limited ownership is not an oxymoron.

Another important distinction here is that between legal and effective ownership. These can go together, as when a person owns her car both in law and in fact: she not only has the title, but also possesses actual powers of use, control, and so on over the vehicle. But so too can they come apart. “The means of production belong to all the people,” proclaimed the Soviet Union’s constitution, but these were just words, for in reality democratically unaccountable bureaucrats and party officials grasped all the important economic levers. Something similar could be said of the relationship between shareholders in large capitalist corporations, on the one hand, and management and executives on the other: the former have “paper” ownership, but it is the latter that really exercise control. In general, it is effective rather than merely legal or formal ownership that is of interest in the present context. Capitalists and socialists alike want to realize their preferred patterns of ownership not just on paper, but also in reality.

b. Private, State, and Social Ownership

To understand socialism, one must distinguish between three forms of ownership. Under private ownership, individuals or groups of individuals (for example, corporations) are the primary agents of ownership; it is they who enjoy the various rights of use, control, transfer, income generation, and so on discussed above. Under state ownership, the state retains for itself these rights, and is thus the primary agent of ownership. Both of these forms of ownership should be familiar to anyone who has frequented a business or driven on an interstate highway.

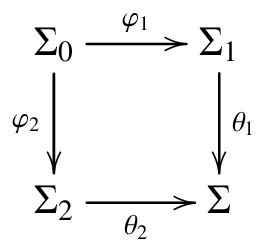

Much less familiar is the key socialist idea of social ownership. Social ownership of an asset means that “the people have control over the disposition of that asset and its product” (Roemer, A Future for Socialism 18). Social ownership of the means of production, then, obtains to the degree that the people themselves have control over these means: over their use and over the products that eventuate from that use. This is a conceptually simple idea, but it can be difficult to grasp its practical implications. How, in concrete terms, could social control over the means of production be realized?

Historically, socialists have struggled to answer this question, and for good reason: it is not at all obvious how meaningful control over something as massive and complex as a modern economy might be shared across tens or even hundreds of millions of people. Broadly speaking, socialists have identified two main strategies of socialization. The first seeks to socialize the economy by nationalizing it. The second seeks the same end by radically decentralizing and democratizing economic power. These strategies will be investigated in greater detail below (see section 8), but for now a few orienting remarks are in order.

First, regarding nationalization: state ownership functions as a vehicle for socialization only to the extent that the people are themselves in control of the state. Otherwise nationalization amounts to little more than statism, not socialism; it constitutes economic rule by state officials rather than by society as a whole. Any genuinely socialist program of nationalization, then, must adhere to a two-part recipe: nationalize the economy, but also democratize the state, thereby putting the people in control of the economy at one remove.

This second step has proven rather elusive in practice. It was not accomplished—indeed, it was not even really attempted—by the so-called “socialist” authoritarianisms of the 20th century such as the Soviet Union and China. And certainly considerable barriers to genuine democratization exist even in countries with longstanding liberal democratic traditions, such as the United States. These barriers include the awesome influence of special interests and concentrated wealth on the political process, corporate domination of political media, voter ignorance and apathy, and so on. Democracy—popular control over the state—is, in short, an ideal easier praised than implemented, even under favorable conditions. However, these considerable practical problems aside, there seems to be nothing incoherent in principle with the idea of a genuinely socialist—because genuinely democratic—program of nationalization.

Or is there? Many socialists argue that state ownership can never fully realize socialism’s promise, no matter how democratic the relationship between the people and the state. This is because real social ownership involves not only control-at-a-remove, so to speak, but also active involvement and participation. On this conception, it is not enough for democratically accountable politicians and bureaucrats to steer the economy in your name; rather, you must do (or at least have the real opportunity to do) some of the steering yourself. The core idea here is well expressed by Michael Harrington:

Socialization means the democratization of decision making in the everyday economy, of micro as well as macro choices. It looks primarily but not exclusively to the decentralized, face-to-face participation of the direct producers and their communities in determining the matters that shape their social lives (197).

In a socialist society, average, everyday people must be active rather than passive, empowered rather than subordinated, involved rather than excluded. But if this is what genuine socialization requires, then socialism is

not a formula or a specific legal mode of ownership, but a principle of empowering people at the base, which can animate a whole range of measures, some of which we do not yet even imagine (Harrington, 197).

The point is not that nationalization can never play a role in making socialism real, but that it cannot play the outsized role often assigned to it.

But if socialists should not rely exclusively on nationalization, to what else should they appeal instead? Different socialists will answer this question in different ways, as we will see in section 8. But most would recommend leavening democratically controlled state ownership with sizable helpings of workplace democracy (as found, for instance, in the Mondragon and La Lega cooperatives in Spain and Italy, respectively), social control over investment, and various other measures to economically empower local communities and individuals (for instance, the “participatory budgeting” process found in Porto Allegre, Brazil, through which citizens meet in popular assemblies to decide how the city’s resources should be spent). By knitting together nationalization of major industries with these and other programs and initiatives, socialists hope to bring to fruition the “truly audacious project of empowering people to take command of their everyday lives” (Harrington, 197).

c. Economic Systems as Hybrids

In principle, an economy could be wholly capitalist, statist, or socialist. An economy would be wholly capitalist just in case all its productive assets were privately controlled; wholly statist, provided all such assets were state-controlled; and wholly socialist, provided all such assets were socially-controlled. While these are coherent theoretical possibilities, they have not been implemented in practice. In reality, all economies are hybrids that blend together private, social, and state ownership. It is better, then, to think of capitalism, statism, and socialism “not simply as all-or-nothing ideal types of economic structures, but also as variables” (Wright, 124). According to this analysis, an economy can be more or less capitalist, socialist, or statist, depending on the particular balance it strikes between the three forms of ownership.

For example, even in the United States—widely seen as a bastion of capitalism—the state plays a considerable role in controlling economic activity and in distributing the proceeds thereof. Does this mean it is a statist or perhaps even a socialist economy? No. Economies should be individuated with reference to their dominant mode of ownership. Since capitalist ownership dominates the United States’ economy—most of its productive assets being privately owned—it should be thought of as capitalist, albeit with some non-capitalist aspects. Similarly, an economy within which most productive assets are socially controlled should count as socialist, even if (as would almost certainly be the case) it also included statist or capitalist elements.

2. Socialism vs. Communism in Marxist Thought

Although this article focuses on socialism rather than Marxism per se, there is an important distinction within Marxist thought that warrants mention here. This is the distinction between socialism and communism.

Both socialism and communism are forms of post-capitalism. Both feature social rather than private ownership of the means of production. Both, within Marxist orthodoxy, reject market production for profit in favor of planned production for use. But beyond these important similarities lie significant differences. In the Critique of the Gotha Progam, Marx’s fullest discussion of these matters, he divides post-capitalism into two parts, a “lower phase” (later called “socialism” by followers of Marx) and a “higher phase” (communism). The lower phase follows immediately on the heels of capitalism, and so resembles it in certain ways. As Marx memorably puts this point, socialism is “in every respect, economically, morally and intellectually still stamped with the birth marks of the old society from whose womb it emerges” (Critique of the Gotha Program 614). These capitalist “birth marks” include:

- Material scarcity. Like capitalism, socialism does not overcome scarcity. Under socialism, the social surplus increases, but it is not yet sufficiently large to cover all competing claims.

- The state. Socialism transforms the state but does not do away with it. What was a “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie” under capitalism becomes a “dictatorship of the proletariat” under socialism: a state controlled by and for the working class. (Since workers make up the vast majority, this is less authoritarian than it sounds.) Workers must seize the state and use it to implement, deepen, and secure the socialist transformation of society. Only after this transformation is complete can the state “wither away”, and the “government of people” be replaced by the “administration of things”.

- The division of labor. Socialism, like capitalism, will feature occupational specialization. Having developed under capitalist educational and cultural institutions, most people were socialized to fit narrow, undemanding productive roles. They are not, therefore, “all around individuals” capable of performing a wide variety of complex productive tasks. Accordingly, socialism must feature a broadly inegalitarian occupational structure. As under capitalism, there will be janitors and engineers, nurses’ aides and surgeons, factory workers and planners.

- Finally, under socialism (many) people will retain certain capitalist attitudes about production and distribution. For example, they expect compensation to vary with contribution. Since contributions will differ, so too will rewards, leading to unequal standards of living. Turning from distribution to production, many socialist producers will, like their capitalist predecessors, regard work as merely a “means to life” rather than “life’s prime want”. They work, in short, to get paid, rather than to develop and apply their capacities or to benefit their comrades.

So in all of these ways, the “lower phase” of post-capitalism resembles its capitalist predecessor. Over time, however, these capitalist “birth marks” fade, all traces of bourgeois attitudes and institutions vanish, and humanity finally achieves the “higher phase” of post-capitalist society, full communism.

What would “full communism” be like? Marx never answered this question in detail—and indeed, he disparaged as utopian those socialists who focused excessively on “drawing up recipes for the kitchens of the future”—but from his brief remarks about communist society certain broad outlines can be discerned. Perhaps his most famous description of communism comes in the following passage from the Critique of the Gotha Program:

In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and therewith also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished; after labor has become not only a means of life but also life’s prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-round development of the individual, and all the springs of cooperative wealth flow more abundantly—only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banner: from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs (615):

Unpacking this passage, we see that Marx makes all of the following claims about communism:

- It has done away with the division of labor, especially that between mental and physical labor;

- Attitudes towards work have changed (perhaps in part because work itself has changed). Communist producers regard work as both instrumentally and intrinsically valuable: they see work not merely as a means to life, but also as “life’s prime want”;

- Human beings themselves have changed under communism, becoming “all-around”, highly developed individuals (rather than the stunted, one-sided creatures that so many of them were under capitalism and perhaps even under socialism);

- Material scarcity has been eliminated or at least greatly attenuated, as “the productive forces have increased” and thus “all the springs of cooperative wealth flow more abundantly”;

- As a result of all these changes, communist society is able to conform to the famous principle: from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs—thus severing the link (found in communism’s “lower phase”) between contribution and reward.

Not only will communism (unlike socialism) do away with class, material scarcity, and occupational specialization, it will also do away with the state. As noted above, the state begins to wither away under socialism. But this process is not completed until the “higher phase” of full communism, for it is only in that phase that lingering class antagonisms are finally eradicated. With these antagonisms cleared away, the state has nothing to do—no class conflict to manage, no further function to perform—and so, like a vestigial limb, it gradually atrophies from disuse. Or, as Engels famously puts this point in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific,

State interference in social relations becomes, in one domain after another, superfluous, and then dies out of itself; the government of persons is replaced by the administration of things, and by the conduct of processes of production. The state is not “abolished”. It withers away (91).

In sum, within Marxist theory socialism and communism are very different indeed. Although both eradicate private property and profits, only the latter also eliminates the division of labor, the state, material scarcity, and perhaps even conflict itself. It is only under communism that mankind completes its ascendance from the “kingdom of necessity” into the “kingdom of freedom” (Engels 95).

3. Why Socialism? Economic Considerations

Is socialism worthy of allegiance, and if so, why?

The standard normative argument for socialism is comparative. Socialists typically single out certain moral and political values, argue that these values are poorly served under capitalism, and then support socialism by contending that these values would fare better—not necessarily perfectly, but better—under socialism. Values drawn upon by socialists vary, but usually include democracy, non-exploitation, freedom (both formal and effective), community, and equality. Sections 4–7 discuss these values and their alleged connections with socialism.

But before turning to these explicitly normative arguments, a word should be said about the purely economic case for socialism. (Since this article’s focus is normative rather than economic, this section will be brief.) Capitalism, many socialists hold, is wild and wasteful, prone to great booms and tremendously destructive busts. The argument goes like this: capitalist competition greatly augments society’s forces of production. Each firm, merely to stay in business, must innovate. As a result, productivity soars. Ever more output can be produced for ever fewer inputs, labor included. Abundance looms.

But this very abundance, paradoxically, is an economic problem. Gluts drive down prices as supply overwhelms demand. Profits decline. Firms, forced to cut costs, sack workers and slash wages. As unemployment and economic insecurity mount, demand plummets still further: people simply don’t have much money to spend. With reduced demand comes reduced opportunities for profits, hence, reduced production. What was a boom has turned into a bust, and society faces the absurd spectacle of idle farms next to hungry people; empty shoe factories beside shoeless workers; foreclosed houses alongside the homeless.

Capitalism, then, makes possible universal abundance. But its central features—market competition, the pursuit of profits, and private property—ensure that this possibility will never be realized. In Marxist language, there is a deep “contradiction” between capitalism’s “forces of production” and its “relations of production”, a contradiction that nothing short of socialist revolution can solve. Society must overthrow capitalist productive relations, replacing anarchic market production for profit with planned production for use. Only then will humanity eliminate the ridiculous concatenation of vast productive potential alongside vast unmet needs. Or so the socialist argument goes.

Socialists find further economic faults with capitalism. Capitalism misallocates resources towards producing what is profitable rather than what is needed. True, what is needed can sometime be profitable. But often the two categories come apart. Think, the socialist will say, of the vast resources spent producing luxuries for the rich, while the needy go without. Or consider the underproduction of critical, but unprofitable, antibiotics, even as “lifestyle drugs” (like Propecia, for baldness) roll off the production line.

Capitalism is also inefficient in its use of human labor power. Capitalism functions best when there exists a “reserve army of the unemployed,” in Marx’s phrase. The credible threat of unemployment reduces workers’ salary demands and increases their work effort. But unemployment means idle workers: able bodied people, willing to work, who cannot find an outlet for their productivity. This is a waste, and it would not exist under socialism (or so it is claimed.)

Further, capitalism allows an entire segment of the (able-bodied) population to live without working: namely, the independently wealthy, who can simply live off investment income. This, again, is wasteful; were these people recruited into the labor process, labor time for the rest could decline. Finally, capitalism misdirects the labor of many of those it does employ. Just think, the socialist will say, of the legions of lawyers, advertisers, marketers, and financial workers. Such workers (and others beside) perform no real productive function. Their jobs are necessary only within the framework of capitalism itself. In a socialist economy, there is no need for marketing, financial speculation, or lawyers specializing in mergers and acquisitions. Socialism would free people currently doing these tasks to apply their talents in a more useful way. Marketers could become teachers; financiers, farmers. And we would all be the better for it.

In sum, socialists seek to upend the common sense view of capitalism. Most people take it for granted that whatever its normative flaws, at the very least capitalism ‘delivers the goods,’ so to speak. Not so, replies the socialist. Because it is prone to economic crises, and is wasteful and inefficient in its use of the means of production (including human labor), capitalism’s economic bona fides must be questioned.

4. Why Socialism? Democracy

The article turns now to the normative case against capitalism and in favor of socialism, starting with democracy.

Democracy means rule by the people, as opposed to rule by the rich, or rule by the excellent, or, more generally, rule by any part of the people over the rest. Systems plausibly claiming to be democratic can vary along at least three dimensions. They can bring a broader or a narrower range of issues under democratic jurisdiction; their members can be more or less directly involved in the exercise of political power; and they can insist upon greater or lesser equality of influence (or perhaps opportunity for influence) over political processes. Call these the scope, involvement, and influence dimensions, respectively.

Other things being equal, as involvement, scope, and equality of influence increase, so too does democracy. Thus it can make sense to say that one democratic system is “more democratic” than another. So too, it is possible to compare different democratic ideals in terms of their “democratic-ness”. A principle or ideal that insists upon maximal equality of influence, for instance, is (other things equal) more democratic than a principle or ideal that does not.

Socialists are radical democrats. They do not merely profess rule by the people; they also interpret that ideal in a highly democratic way, opting for maximalist or near-maximalist positions along all three of the just-mentioned dimensions. They want democracy to have very broad scope; they want citizens to be highly involved in democratic processes; and they want citizens to have roughly equal opportunities to influence these processes. And they typically argue, further, that the democratic ideal, understood in this rich and demanding way, militates against capitalism and in favor of socialism. This article will focus on the scope and influence dimensions.

a. Scope

To see this argument, consider first the scope dimension of democracy, which concerns the question: where should the boundary between public and private, between politics and civil society, be drawn? Which issues should be subject to democratic choice? Many socialists endorse something like the following principle:

All Affected Principle: People affected by a decision should enjoy a say over that decision, proportional to the degree to which they are affected.

However, it is a rather short step—or so say socialists—from this intuitively plausible principle to the radical conclusion that economics should be subordinated to democracy, that large swathes of economic life should be politicized and brought under popular control. All that is required to make that leap is the seemingly incontrovertible premise that many economic issues affect the public. When a local business fires 20% of its workers, this affects the public. When financiers withdraw support for a new shopping center, this affects the public. When society’s productive assets are deployed to make yachts for millionaires rather than affordable housing, this affects the public. When corporations pull up roots and relocate production to greener pastures, this affects the public.

In all of these cases (and many others besides), people’s lives are affected—indeed, often profoundly affected—by economic decisions. Do they get a say in these decisions, as required by the All Affected Principle? Not under capitalism, which grants extensive control over such matters to holders of private property rights. Where private property reigns, owners rather than affected parties decide, for example, whether to hire or fire, to invest, to relocate, and so on. From the socialist point of view, this is a serious offense against democracy. Capitalism, socialists claim, depoliticizes what should remain political; it cedes far too much control over common affairs to private parties. It is, in this way, insufficiently democratic.

But if the root cause of this democratic deficit is private control over productive assets, then the solution, or so socialists argue, must be social control over the same. Social property brings into the democratic domain what private property improperly removes. What touches all must be decided by all; economic matters touch all; therefore economic matters must be decided by all. This is the simple but powerful democratic syllogism at the heart of one major argument for socialism, for social rather than private control of the economy. What might social control over the economy look like in practice? Section 8 explores competing answers to this question.

b. Influence

Socialists find further grounds for rejecting capitalism in democracy’s influence dimension. Standardly, democracy is held to require not merely that all citizens have a say, but that they have an equal say. But what does this really mean? To clarify, suppose that A and B have equal voting rights, but A, being rich, educated, and leisured, has a greater chance to influence the political process than B, who is poor, uneducated, and short on free time (he must work long hours to make ends meet). Do A and B have an “equal say”, in the sense required by democracy?

Nearly all socialists, and indeed, many non-socialists, would say “no”; they would detect a democratic deficit in this scenario, for they typically see democracy as requiring not merely formal equality of opportunity for political influence but also substantive or fair equality of opportunity for political influence. On this view, it is not enough for A and B to enjoy identical legal protections to vote, to run for office, to engage in political speech, and so on. Instead, genuine democracy requires (over and above this merely legal equality) that equally talented and motivated citizens have roughly equal prospects for winning office and/or influencing policy, regardless of their economic and social circumstances—or something along these lines.

Now, capitalism clearly can implement formal political equality. Many capitalist societies grant their citizens equal rights to vote, to run for office, and so on. But can capitalism implement substantive political equality?

Many socialists think not. Capitalism, they point out, generates steep economic inequalities, dividing society into rich and poor. But in a variety of ways, the rich can translate their economic advantages into political ones. This translation can occur relatively directly, as when the rich buy political influence through campaign contributions, or when they hire lobbyists to steer legislative priorities (sometimes going so far as to draft laws themselves). Or it can occur relatively indirectly, as when the wealthy use their ownership of media to shape public opinion (and thus the political process), or when capitalists threaten to take their money out of the country in response to disliked (usually leftist) policies, thereby limiting what government can do.

But whether moneyed interests affect politics directly or indirectly, the net result is the same: capitalism amplifies the voices of the rich, enabling their concerns to dominate the political process. Indeed, some socialists, pressing this objection to its logical conclusion, contend that “democracy” under capitalism is really little more than oligarchy—rule by the rich—covered by a democratic fig leaf. Or, as Vladimir Lenin put this point: “Democracy for an insignificant minority, democracy for the rich—that is the democracy of capitalist society” (79).

Sophisticated defenders of capitalism respond by arguing that capitalism’s democratic deficits can be repaired within a fundamentally capitalist framework. Campaign finance reform, regulation of lobbying, restrictions on corporate domination of media, even limitations on the movement of capital across borders would, together, do much to restore or preserve political equality amidst capitalist economic inequality, and yet none of them are incompatible with capitalism per se. It follows (capitalists argue) that there is no need to throw out the baby of capitalism with the bathwater of political inequality. Sufficiently reformed, capitalism can indeed realize not just formal political equality but also substantive political equality.

The question, socialists would reply, is whether these reforms would ever be chosen by political elites under capitalism. Will capitalist oligarchs willingly undercut the very basis of their rule by socializing control over mass media, installing real campaign finance reform, limiting capital flows, and so on?

Would socialism perform any better than capitalism on this “influence” dimension of democracy? Would it enable equally talented and motivated citizens to have roughly equal prospects for influencing politics? Socialists argue that it would. Because it eliminates class, socialism eliminates the major threat to substantive political equality. (Of course, other forms of exclusion, such as racism and sexism, must also be overcome.) Wealthy property owners will not dominate the political process at the expense of the poor and unpropertied because the latter will be an empty set. Everyone will be a wealthy property owner, in the sense that everyone will share control over the means of production and will have access to a dignified standard of living. Everyone will therefore have roughly equal economic resources to bring to bear on the political process.

Put differently, whereas capitalism attempts to secure political equality despite massive economic inequalities, socialism attempts to secure political equality in large part by eliminating these inequalities.

5. Why Socialism? Exploitation

According to many socialists, one of capitalism’s central moral failings is that it is exploitative. Socialism, by contrast, would not be exploitative—or so these socialists allege—and this is one of the main reasons for preferring it to capitalism.

But what is exploitation? Is capitalism truly exploitative? And would socialism really eliminate exploitation? This subsection explores socialist answers to these questions.

a. Exploitation as Forced, Unpaid Labor

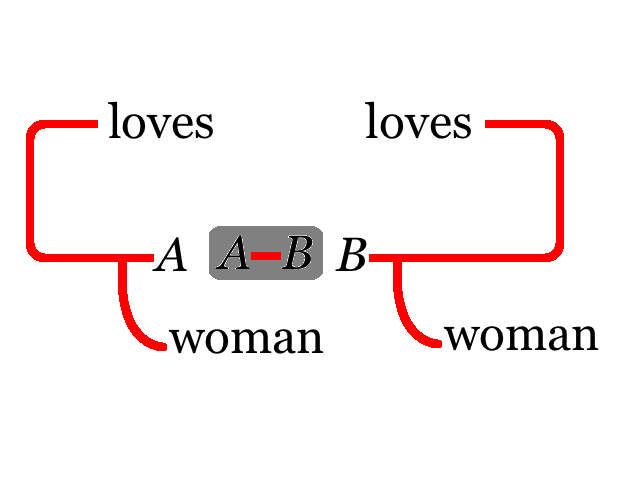

Although there is no universally accepted account of exploitation, Jeffrey Reiman’s Marx-inspired suggestion that exploitation is “a kind of coercive prying loose of unpaid labor” provides a good framework for discussion (3). On this account, a person is exploited if and only if she is forced to work for free. Feudal serfs, for example, were exploited because they were legally and physically compelled, at sword-point if necessary, to spend part of their working time toiling in the lord’s fields for nothing in return. This was forced, unpaid labor of the most obvious sort, and it constituted a serious form of exploitation.

But are capitalist employees exploited? At first glance, it would appear not. Workers get paid wages, so it doesn’t seem as if they are working for free. Nor does it appear that workers are forced to work. Capitalism, being a system of “free labor”, grants workers ownership over their labor power and entitles them to sell it—or not—as they please. So where is the force supposedly inherent in the capital/worker relationship?

Take the issue of force first. In general, a person is forced to do something X whenever she has no reasonable alternative to doing X. Workers, then, are forced to sell their labor power to capitalists just in case they have no reasonable alternative to doing so. But of course they don’t have a reasonable alternative, or so some socialists contend. Their argument is simple. Everyone must make a living. There are, under capitalist property relations, only two main ways to do this: one can live off of investment or property income, or one can live off of wages. By definition, workers cannot pick this first option; they don’t own means of production, so they can’t live off of income generated by such ownership. This leaves wage labor as the only acceptable option. True, workers are formally free to decline capitalist employment, but this does not represent a reasonable option since its consequences are so dire: starvation or, in more enlightened circumstances, life on the dole. Workers therefore have no minimally reasonable choice but to sell their labor power to owners of means of production.

It follows that workers are forced to work for capitalists, even if they are not so forced by capitalists (or indeed, by anyone else). The forcing in question is structural rather than agential; as Reiman explains, it is “an indirect force built into the very fact that capitalists own the means of production and laborers do not.” Or, as Marx puts this point, it is the “the dull compulsion of economic relations” rather than “direct force” that “completes the subjection of the laborer to the capitalist” (Capital Vol. I, 737).

Not all socialists accept this argument. G.A. Cohen, for example, suggests that individual workers do have a reasonable alternative to selling their labor power: they can become capitalists themselves (“The Structure of Proletarian Unfreedom”). Not overnight, perhaps, but with enough scrimping and saving, is it not possible for an individual worker to start a business of her own? Cohen concludes that individual workers are not forced to sell their labor power. (He also argues that workers are “collectively unfree”—unfree as a class—since not all, or even many, workers can escape their class at the same time; the economy can absorb only so many small business owners at any given moment. But this alleged collective unfreedom of workers, though interesting and important, is peripheral to our present topic and so must be set aside.)

In response, some socialists question whether opening a small business really represents a reasonable option for most workers. For one thing, many workers simply can’t save enough to open such a business: their wages are just too small relative to the cost of living. For another, even if a worker is able, through years of thrift, to open his own business, most businesses fail, often leaving the owner much worse off financially than she would have been had she simply remained a wage laborer. Pulling together these ideas, one critic of Cohen concludes that “escaping into the petty bourgeoisie…is a reasonable alternative only for a tiny minority of workers. Thus the vast majority of working-class individuals are forced to sell their labor power to earn a living” (Peffer, 152).

But even if Cohen is wrong, and individual workers are forced to sell their labor power, notice that it does not yet follow that workers are exploited. For forced labor alone does not exploitation make. Exploitation, as described above, involves forced, unpaid labor. Let us turn, then, to the issue of compensation, and in particular, to the question of whether workers toil (at least in part) for free.

Again, surface appearances cut against the socialist position. Wage laborers standardly receive an hourly wage. If they work, say, eight hours, they get eight hours’ pay. It certainly seems, then, that workers receive full compensation for their toil. Perhaps this compensation is unfairly low, but that is a different issue: the exploitation charge, standardly construed, is that workers are forced to work for no pay, not that they are forced to work for low pay.

But probe more deeply, some socialists contend, and the unpaid nature of much work under capitalism becomes clear. To see their argument, it helps to start with an easier case: feudal production. Under feudalism, serfs spent part of their working time working in their own fields and the rest working in their lord’s fields. They kept whatever they could grow on their own plots, and surrendered whatever they grew on the lord’s. Put differently, serfs received compensation for part of their working time, but no compensation at all for the rest of it. A great deal of their work, then, was wholly unpaid: a fact that was very obvious to all involved, given the physical separation between paid work (on the serf’s fields) and unpaid work (on the lord’s).

Marxists argue that precisely the same division between paid and unpaid work exists under capitalism. Workers spend the first part of their working day working, in effect, for themselves. This is the part of the day during which they produce the equivalent of their wages. Marx calls this “necessary labor time”. But the working day does not stop there. Indeed, it cannot stop there, for if it did, there would be no “surplus product” for the capitalist to appropriate, and thus no reason for the capitalist to hire the worker in the first place. So the capitalist requires the worker to perform “surplus labor”, which is just labor beyond “necessary labor”: labor beyond what is required to produce value equivalent to the worker’s wage. The value produced during surplus labor time, Marx calls “surplus value”. Crucially, this surplus value belongs to the capitalist rather than the worker, and is the source of all profits.

To illustrate, consider a worker who produces 1 widget per hour over the course of an eight-hour shift, thus yielding eight widgets in total. Her boss takes these widgets, sells them, and then returns part of the proceeds to the worker in the form of a wage. But this wage must be less than what the capitalist reaped by selling the widgets. Otherwise the capitalist would have nothing left over as profit. To fix ideas, suppose that the worker’s daily wage is equivalent to the value of 2 widgets. To produce this value, she had to toil for 2 hours (at 1 widget per hour). Yet her shift lasts 8 hours. It follows that she spent 2 hours working for herself, and 6 hours working for her boss: which is to say, 6 hours working for free.

We can now appreciate Marx’s remark that “the secret of the self-expansion of capital [that is, the secret of profit] resolves itself into having the disposal of a definite quantity of other people’s unpaid labor” (Capital Vol. I, 534). Profits, on Marxist analysis, are possible only through the extraction of unpaid surplus labor from workers. Wage workers toil gratis no less than serfs. That the division between paid and unpaid labor under capitalism is temporal rather than physical or spatial (as under serfdom) makes this division harder to see, but it does not in any way diminish its reality—or so the socialist argument goes.

b. Eliminating Exploitation

How exactly is socialism supposed to eliminate exploitation? Notice that it would not eliminate work itself, as Marx writes, “Just as the savage must wrestle with Nature to satisfy his wants, to maintain and reproduce life, so must civilized man, and he must do so under all social formations and under all modes of production” (Capital Vol. III, Ch. 48). So even under socialism, work must be done.

However, it does not follow that people must be forced to do it. Society could eliminate the compulsion to labor by partly decoupling income (or access to basic resources more broadly) from work. Philippe van Parijs’s “unconditional basic income” represents one way to achieve this decoupling. On his proposal, which has attracted significant support from socialist quarters, each citizen, no matter how rich or how poor, would be paid a monthly income, set as high as possible, and in any case sufficient to live with dignity. This income would come without any strings attached. In particular, it would not be conditional on working, seeking work, or training for future work. It would go to all members of the political community: leisured surfers off of Malibu no less than industrious steelworkers in Pittsburgh.

Perhaps the economic feasibility of such a proposal may be questioned. But for present purposes, the important thing to appreciate is the way in which a UBI (as it is known) gives each person the “real freedom” to drop out of the paid labor force, thereby eliminating both the compulsion to work and (therefore) exploitation.

From a socialist perspective, there are at least two potential problems with this way of eliminating exploitation.

First, a UBI enables people to live off the hard work of others—no reciprocation required. Again, surfers get the check no less than people with paid employment. But socialists complain when capitalists live off the work of others; shouldn’t they complain when surfers (and so forth) behave similarly?

Second, there is nothing uniquely socialist about a UBI. Capitalist no less than socialist societies can implement a UBI, thereby enabling everyone to live decently without working. A defender of capitalism might therefore insist that when it comes to exploitation, capitalism and socialism are on all fours: both are equally susceptible to exploitation and equally able to enact the policies needed to eliminate it.

In response, socialists might point to the second necessary feature of exploitation, non-compensation. Notice that compensation takes many forms. Acquiring exclusive control over a sum of money, or over a bundle of resources, is one of them. But so too is acquiring a share of control over resources. Say that you and I work to build a tree house which we then jointly control. Neither of us has exclusive say over the tree house. And yet it would be wrong to conclude that our labors have gone uncompensated. We have been compensated; it’s just that our compensation comes in the form of common rather than private property.

This is precisely the sense in which all labor is compensated under socialism. Workers own the means of production together; they (therefore) own the surplus generated by these means. True, they do not own this surplus privately. They share control over its disposition and use. But shared control can be a form of compensation no less than private control.

Under capitalism, workers have private ownership over their wages (and the things these wages buy) but no ownership at all over most of what they produce. This is the sense in which most of their laboring activity goes uncompensated. Workers produce a surplus, hand it over to capitalists, and are then cut out of the picture; their bosses are free to do with the surplus whatever they like: consume it, invest it, burn it, and so forth. Under socialism, by contrast, workers have private ownership over their wages (or, in a money-less economy, over resources for personal use) and collective ownership over the social surplus they produce. They both make the surplus and share control over how to use this surplus. At no point, then, are socialist producers toiling ‘for free’, since their labors go towards building an economy that is shared and controlled by all. It’s as if everyone made a gigantic tree house that everyone is then free to use and to help govern.

So, contrary to the capitalist objection raised 4 paragraphs back, it seems that socialism is uniquely well positioned to eliminate exploitation. Both socialism and capitalism could, in principle, eliminate forced labor by attenuating the link between income and work. But only socialism can ensure that all work is compensated through common ownership of the social surplus. Thus socialism expunges exploitation from economic life even absent something like a UBI, whereas the same cannot be said of capitalism.

Against this argument, critics might reply that the kind of ‘compensation’ for surplus labor promised by socialism is wholly inadequate. Under capitalism, the worker’s surplus is appropriated by the capitalist; under socialism, the worker’s surplus is appropriated by society. From the worker’s point of view, this may seem a distinction without a difference. Both appropriations rob the worker of effective control over the fruits of her labor. True, under socialism the worker is a member of the group doing the appropriating, but, as merely one of millions of such members, her individual influence over that group is infinitesimal. Is it plausible to regard her tiny sliver of decision-making power over the surplus as ‘compensation’ for her surplus labor? Arguably not, in which case socialism does not actually eliminate exploitation.

6. Why Socialism? Freedom and Human Development

Many socialists point to considerations of freedom, broadly understood, to support socialism over capitalism.

Freedom comes in many varieties. This article will discuss two. Formal freedom involves the absence of interference. Effective freedom involves the presence of capability. A person who is unable to walk has the formal freedom to ascend a steep flight of steps—assuming that no one will interfere with her attempt—but lacks the effective freedom to do so.

a. Formal Freedom

It is sometimes suggested that socialism fares poorly with respect to formal freedom. There are two main grounds for this contention, one historical, the other conceptual.

Historically, many countries claiming to be socialist trampled basic liberties such as freedom of expression and religion. They imprisoned and killed political dissidents and other ‘enemies of the people’. Far from being free societies, they were deeply oppressive ones.

Some critics of socialism suggest that this historical correlation between socialism and oppression was no accident. Rather, it reflects a deep flaw in socialism’s design. Socialism concentrates economic and political power in the hands of the state. Abuse is inevitable under such conditions. Milton Friedman, building off of this insight, famously posited a necessary connection between capitalism (which, unlike socialism, disperses economic power rather than concentrating it) and freedom: not all capitalist societies are free, but all durably free societies must be capitalist.

Socialists concede the heart of Friedman’s point, but argue that it does not undermine their position. Friedman, they say, was right to warn against excessive centralization of power. But he was wrong to suggest that socialism necessarily requires said centralization. The contemporary socialist ideal is profoundly democratic and decentralized; it seeks to disperse economic power, not concentrate it. It aspires to an economy and a society controlled from the broad bottom, not the narrow top. So the kind of socialism that contemporary socialists embrace is simply different than the kind of ‘socialism’ targeted by Friedman’s critique. Put differently, Friedman’s worry attacks a view held by very few socialists today—or so it might be argued.

Turning to a different objection, it is sometimes suggested that on purely conceptual grounds socialism is a more restrictive society than capitalism. The argument for this claim is simple. Capitalism permits private ownership of productive assets; socialism does not. Socialism therefore provides less formal freedom than capitalism. It interferes with various economic activities that capitalism allows. Thus, if what you value is formal freedom, then you should prefer capitalism to socialism.

The trouble with this argument, as pointed out by G.A. Cohen, is that it “see[s] the freedom which is intrinsic to capitalism [but not] the unfreedom which necessarily accompanies capitalist freedom” (“Capitalism, Freedom, and the Proletariat” 150). Capitalism does indeed allow some things that socialism forbids: for example, opening a business. But the converse is also true. To use Cohen’s example: I am free to pitch a tent on common land. I am not free to pitch a tent on land that you own privately. Should I try, the state will interfere, thereby reducing my formal freedom. Private property’s effects on formal freedom, then, are not uniformly positive, but mixed. Private property extends formal freedom to owners even as it withdraws it from non-owners. As Cohen writes, “To think of capitalism as a realm of freedom is to overlook half its nature” (“Capitalism, Freedom, and the Proletariat” 152)

Of course, precisely the same can and indeed must be said of socialism. All systems of property, whether capitalist or socialist, exert complex effects on formal freedom; all such systems necessarily distribute both freedom and unfreedom. But in light of this complexity, our guiding question here—which system, capitalism or socialism, provides more formal freedom?—is probably unanswerable. All we can say with confidence is that these systems provide differently shaped zones of formal freedom; each extends formal freedom in some ways while restricting it in others. However, it seems extremely difficult, perhaps impossible, to determine which of these zones is ‘larger’ overall. At the very least, defenders of capitalism must say a great deal more to establish that capitalism is, a priori, a freer society than socialism.

Socialists score this particular fight a draw.

b. Effective Freedom

Whereas socialists tend to play defense regarding formal freedom, they go on offense when discussing effective freedom.

Effective freedom, again, involves the capacity to accomplish one’s ends. This implies but goes beyond formal freedom. Say that my goal is to complete a marathon. One way I can fail to accomplish this goal is by meeting with agential interference. If you physically restrain me from participating in the race, you undermine my effective freedom by undermining my formal freedom. However, effective freedom usually requires much more than the mere absence of interference. I can actually complete a marathon, for example, only if a host of further conditions are in place. Some are broadly social: I must live in a society in which marathons occur. Others are broadly economic: I must be able to afford all the costs associated with training for the race, traveling to the race, entering the race, and so forth. And there are physical or “internal” factors as well. I can’t finish the marathon unless I have sufficient mobility and endurance. All of which is to say that effective freedom depends upon a wide range of factors, many of which have nothing to do with human interference per se.

Now, in a good and just society, which effective freedoms—which “capabilities,” as they are sometimes called—would people have? The typical socialist response runs as follows. At a minimum, everyone must have the effective freedom to meet their basic needs for food, shelter, health care, and so on. With these capabilities in place, people are able to survive. This is a crucial accomplishment, and one demanded by minimal standards of justice and decency. However, a truly good society must set its sights higher; it must enable people not merely to survive, but also to flourish.

And what is human flourishing? Socialists standardly accept a broadly Marxist/Aristotelian account according to which the good life centrally involves not just the passive pleasures of consumption (watching TV, eating tasty food, and so on) but also the more active and enduring satisfactions of “self-realization”, which can be defined as the “development and application of a person’s talents in a way that gives meaning to his or her life” (Roemer, A Future for Socialism 3). Mastering an instrument, playing a sport, solving a physics problem, writing an article, building a shed: these are all examples of potentially self-realizing activities.

Such activities typically have a steep “learning curve” that makes them frustrating at first, but deeply gratifying over the long haul. In this, they contrast sharply with consumption activities, which have the opposite hedonic profile: watching TV is immediately gratifying, but its charms wane with repetition. This contrast is one reason why self-realization is (according to many socialists) more important to human flourishing than consumption. A life replete with consumption but lacking in self-realization becomes stale, cramped, unsatisfying. Indeed, at the limit, it veers towards meaninglessness. It is only through the development and exercise of one’s higher powers and talents that one leads a truly human existence—or so the socialist view has it.

So a genuinely good and just society, then, is one in which “the free development of each is the condition of the free development of all,” as Marx and Engels declare in the Communist Manifesto: it is one in which each person has real access to the material, social, and political preconditions for human development and self-realization. But how, precisely, does any of this amount to an argument for socialism? The answer is that socialists typically see capitalism as a serious barrier to self-realization, a barrier that nothing short of socialism can remove. As Jon Elster puts it, capitalism “offers [the opportunity for self-realization] to a few but denies it to the vast majority” (Introduction to Karl Marx 43). Socialism, by contrast, would democratize self-realization, putting it within reach of average, everyday people for the first time in human history—or so it is claimed.

To fill in these claims, consider the material and social preconditions for self-realization. To develop and apply one’s talents in a way that gives meaning to life, one must, at a minimum, have one’s basic needs met. People who are sick, hungry, or homeless are simply not in a good position to develop and exercise their higher talents. However, since capitalism reliably leads to poverty via frequent busts, structural unemployment, downward pressure on wages, and so on—or so socialists will claim—it therefore reliably depresses access to self-realization for a significant portion of the population. Socialism, by contrast, would eliminate poverty and thus would eliminate this potent material barrier to self-realization.

Suppose, however, that basic needs are met: what else is required for self-realization? Time. Now, under capitalism, most people are forced, through lack of private property, to perform wage-labor for a living (see section 5.a). Their days are thus divided into two parts: working time and leisure time. But time spent in a capitalist workplace is, for the vast majority of people, hardly time for self-realization. Capitalist jobs are oriented around the demands of profit, not self-realization. And quite often, the most profitable way to organize work is to “deskill” it: to make it simple, routine, even stultifying (Braverman).

Granted, there are exceptions. Some workers, such as doctors, engineers, college professors, carpenters, have challenging, complex, autonomous, engaging jobs that help bring self-realization and meaning to their lives. But these are the lucky few. More typical is the experience of, say, assemblers, fast food workers, cashiers, poultry-plant operators, secretaries, human resource clerks, and so on and so forth. Saddled with “alienating” jobs like these, workers work merely to live; as Marx writes, they “feel themselves at home only when they are not working, and when they are working they do not feel at home” (Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts). This is not to demean the people occupying these roles, nor is it necessarily to deny the social importance of these jobs. Rather, it is only to point out that these jobs offer little opportunity to develop and exercise complex talents in a way that brings meaning to life. If capitalism’s armies of cashiers, clerks, and so on are to experience self-realization, then, it will have to be off the clock, during their free time.

Yet here we hit upon a further capitalist barrier to self-realization: its unwillingness to expand what Marx called the “realm of freedom,” leisure, by shrinking the “realm of necessity,” work. Despite ever-rising productivity—more output per unit of labor input—working time rarely declines under capitalism. This is, on its face, rather puzzling. After all, there are, in principle, two ways an enterprise could respond to an increase in productivity. It could keep working hours constant while increasing output, or it could keep output constant while cutting working time. Yet capitalist firms consistently choose the first option over the second; they choose to produce more stuff rather than reduce the working day.

What explains this “output bias”? Profits (Cohen, Karl Marx’s Theory of History Ch. XI). Firms do not make more money by reducing working time; they make more money by increasing output. And so we get, under capitalism, a society chronically short on leisure but drowning in consumer goods; we get the familiar harried rat race, albeit with iPhones.

Now, this mountain of stuff must be sold. This requires spending enormous resources on the “sales effort”—marketing, advertising, and so on—so as to stimulate demand. The result is a highly consumerist society in which many people identify the good life with the life of consumption rather than self-realization. This widespread consumerism may be further promoted by a “sour grapes effect”. Denied self-realization by the alienating nature of work and insufficient free time, the capitalist worker decides self-realization isn’t worth having to begin with. Like the fox in Aesop’s fable, he rejects the tasty fruit he cannot have (self-realization) for the blander fruit within reach (consumption).

In sum, for a variety of interconnected reasons, having to do with its tendency to produce poverty, deskill work, provide inadequate free time, and promote a consumerist orientation, capitalism undermines self-realization and therefore human flourishing. Not, admittedly, for all. But for the vast majority, capitalism renders a rich and meaningful life difficult if not impossible to achieve. Or so the socialist argument goes.

How would things differ in a socialist economy? We have already seen that socialism, by (allegedly) eliminating poverty, would eliminate that particular material barrier to self-realization. Regarding work and leisure, socialists argue that because their system places human beings rather than anarchic market forces in control of the economy, it empowers us to prioritize self-realization and expanded leisure in the design and organization of work. Since we control production, we can tailor it to suit our preferences. If we want better, non-alienating work and more free time, we can get it. Admittedly, this would probably result in lower output. With reduced hours and more engaging labor processes, less stuff would be produced. But from the socialist point of view, this is no great tragedy. Past a certain point, more stuff contributes very little to human flourishing. Once a decent standard of living has been secured, self-realization hinges mainly on access to meaningful work and adequate free time. If the price of securing these things is less stuff, so be it. Fewer iPhones in exchange for more meaningful jobs and no rat race: this is a tradeoff that socialists heartily recommend.

7. Why Socialism? Community and Equality

Capitalism is competitive and cut-throat; socialism is cooperative and harmonious. Capitalism divides; socialism unites, or so many socialists have argued. The crucial value in play in these arguments is “community”.

The concept of “community” admits of at least two different interpretations. The first concerns producers’ motivations: what drives people to wake up each day and go to work? Is it fear and greed, or a desire to serve one’s fellows? The latter is the motivation consistent with community, yet it is relentlessly undermined by capitalism (or so socialists claim). The second sense of community concerns limitations on material inequality. When inequalities in living conditions grow too steep, mutual incomprehension results. People dwell in different worlds. This undermines community (in this second sense), or so it may be argued. These two senses of community, and their fates under capitalism and socialism, will be explored more deeply in what follows.

a. Why Produce? Communal vs. Market Reciprocity

As Adam Smith observed, under capitalism “it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest” (Book 1, Ch 2). The baker hands over a loaf only because you pay him. Remove the payment, and he removes the bread. So it goes in a market society, for as G.A. Cohen argues, in such a society productive activity is motivated “not on the basis of commitment to one’s fellow human beings and a desire to serve them while being served by them, but on the basis of cash reward” (Why Not Socialism? 39). Market participants operate on the maxim “serve-to-be-served”; they serve only in order to receive service in return. They strive to give as little as possible while getting as much as they can—“buy low and sell high,” as the saying goes. Indeed, the best-case scenario (by market logic’s lights) is to give nothing and get everything.

Market logic thus locks us into deeply anti-social relations. The marketeer, looking at humanity, sees not comrades or brothers and sisters, but customers and competitors. Predator-like, he sees mere “sources of enrichment” and “threats to success”. The former are to be fleeced, the latter crushed. Yet these are horrible ways to relate to other people. Market society may deliver the goods, but it does so only by bringing out some of the worst aspects of human nature. Or so some socialists argue.

But is there an alternative? Cohen asks us to consider how people behave on a camping trip. If A needs help setting up her tent, does B use her need strategically as a means to self-enrichment? Does he ‘drive a hard bargain’, making his support contingent on receiving something in return? No; that’s not how decent people behave in such a context. Rather, in the standard case, B helps A simply because A needs help. Service in response to need: this is what motivates productive activity on a camping trip.

Now, this is not to say that B’s assistance comes entirely without strings attached. B needn’t be a sucker, so to speak; he needn’t continue to help A if A consistently fails to return the favor. On a camping trip, one reasonably expects some degree of reciprocity. Campers thus occupy a sweet spot between anti-social market predation on the one hand and self-denying altruism on the other. Cohen labels this sweet spot “communal reciprocity,” and describes its content as “serve-and-be-served”. Campers acting on this motivation value both sides of the conjunction. They regard it as intrinsically desirable to serve each other, yet they also do expect some degree of reciprocation. As Cohen explains, “the relationship between us under communal reciprocity is not the market-instrumental one in which I give because I get, but the non-instrumental one in which I give because you need, or want, and in which I expect a comparable generosity from you” (Why Not Socialism? 43).Cohen recognizes an important caveat here: the responsibility to reciprocate is conditional upon ability. Thus, there’s no problem with disabled people receiving support without making a contribution in return.

Such behavior is entirely normal and functional on a camping trip. Communal reciprocity clearly “works” in such a context. But can it work on a massive, society-wide scale? Can millions or billions of strangers serve each other, with tolerable economic results, out of fraternity and benevolence rather than greed and fear?

Skeptics cite two main grounds for doubt. The first is human nature: surely people are simply too selfish, greedy and tribal for communal reciprocity to work on a massive scale. Treating your actual brothers as brothers is one thing; treating total strangers as brothers is quite another.

Socialists reply that human nature is complex. We are indeed greedy and competitive, but so too are we generous and cooperative. Economic context powerfully influences which of these traits predominate. Edward Bellamy, an influential 19th century American socialist novelist and thinker, compares human nature to a rosebush (Ch. 26). Put a rosebush in a swamp, and it will appear sickly and ugly. One might conclude that rosebushes are, by ‘nature’, noxious little shrubs. But this would be a mistake. We know that rosebushes are capable of great beauty, given the right developmental conditions. Yet surely, argues Bellamy, the same goes for human beings. Shaped by capitalism, people appear greedy, cramped, and fearful. But this is only because we’re mired in a metaphorical swamp. Put us in the more hospitable soil of socialism and we, like the rosebush, would blossom; we would display all the fellow-feeling, generosity, and cooperative instincts socialism requires.

Human nature, in short, poses no serious obstacle to socialism. ‘Socialist man’ dwells within all of us, waiting only for the right social conditions to emerge.

But these social conditions simply cannot emerge, for they are infeasible: this is the second skeptical objection. Without markets, economies simply do not function tolerably well—witness the failure of Soviet-style planning. In response, Cohen argues that this is just one data point. It would be overly hasty to write off all non-market alternatives simply on the basis of one failed experiment. He admits that socialists face a “design” problem. They do not now know how to power an economy on generosity and fraternity rather than greed or fear. But design problems often turn out to be solvable with enough ingenuity and attention. Non-market socialists do not currently have the answers. But in the fullness of time, they might—or so Cohen argues.

Before turning to a different community-based critique of capitalism, a powerful challenge to Cohen’s argument should be noted. Jason Brennan points out that socialism cannot lay claim to communal reciprocity by definitional fiat. Socialism is just communal ownership of the means of production. Whether this particular way of structuring property fosters communal reciprocity, leading to a generosity and a “serve-and-be-served” mentality on a wide scale, is an entirely empirical question that cannot be answered from the ‘philosopher’s armchair,’ as it were. Yet when we turn to the empirical record, we find little support for Cohen’s position.

If Cohen were right, then we should expect to see an inverse relationship between markets and various pro-social attitudes and behaviors. We should expect to see greater levels of greed, mistrust, and so on as markets expand and deepen. The most marketized societies should also be the most anti-social. But this is not at all what we find. In fact, we find precisely the opposite. Studies cited by Brennan suggest that market exchange promotes various pro-social attitudes such as trust, fairness, and reciprocity. Brennan concludes that Cohen has it backwards: if we wish to spread camping trip values across society, we should embrace markets, not reject them.

Notice that Brennan’s critique (if sound) damages only non-market varieties of socialism. It does not undermine (and indeed actually provides some support for) market versions of the same. (Market socialism is discussed further in 8.c.)

b. Justice, Inequality, Community

This article has not said very much about equality as a socialist ideal. This may surprise some readers. Isn’t equality of condition one of socialism’s central aims? Indeed, socialism’s allegedly uncompromising egalitarianism is sometimes used as the basis for a reductio ad absurdum of the socialist position. The reductio runs like this: according to socialism everyone must be equal; one way to do this is to ‘level down’ the better off; but this is morally repugnant; so socialism must be rejected. One thinks here of Kurt Vonnegut’s famous anti-egalitarian tale “Harrison Bergeron”, in which an equality-obsessed government knocks the noggins of the more intelligent, bringing them into alignment with their IQ-disadvantaged peers.

The reductio fails because socialists do not advocate equality of condition, at least not in any straightforward sense. Much light has been shed on this issue by the now-voluminous philosophical literature on egalitarianism. Of particular import is the work by philosophers like Richard Arneson and G.A. Cohen on the question: “equality of what”? Insofar as leftists seek equality, what is it that they wish to equalize? Standard options include 1) resources, 2) welfare, 3) opportunities for resources, and 4) opportunities for welfare.

Most philosophers agree that the first two options are non-starters. Equalizing outcomes (as 1 and 2 would do) improperly ignores personal choice and responsibility. The point is nicely illustrated by Aesop’s fable of the grasshopper and the ant. Stipulate that both bugs know that winter is coming, and that both have the capability, that is, the effective freedom, to build a house and to gather adequate supplies. That is to say, both have equal opportunity to provision themselves. Yet only industrious ant chooses to use this opportunity; carefree grasshopper decides to dance and play instead. Fast forward to winter: there sits ant in his house, warm and well-fed, while grasshopper shivers hungrily outside. Now, no matter which metric we use—resources or welfare—ant is clearly much better off than grasshopper. Between the two bugs, a very significant inequality of condition obtains. But does this inequality constitute an injustice?

Interestingly, many socialists would answer ‘no’ to this question. These socialists hold a “responsibility-sensitive” form of egalitarianism sometimes called “luck egalitarianism”. On this view, outcome inequalities (whether measured in resources, welfare, or some other metric) are just if and only if they “reflect the genuine choices of parties who are initially equally placed and who may therefore reasonably be held responsible for the consequences of those choices” (Cohen, Why Not Socialism? 26). By luck egalitarian lights, then, the grasshopper/ant inequality is perfectly just since it reflects divergent choices rather than differences in unchosen circumstances. (Circumstantially, the bugs were identically placed. Both could have prepared for winter. But only ant chose to do so.)

Notice that the luck egalitarian would reach a different verdict if grasshopper and ant were unequal because (say) grasshopper was born without legs, and thus couldn’t provision himself. Then it would be unjust for him to go without food or shelter. For that outcome would reflect factors beyond his control, namely, his unchosen disability, in violation of the luck egalitarian standard.

In sum, contemporary socialist “luck egalitarians” have a nuanced view on equality and justice. Opportunities (for resources, welfare, or whatever) must be equal. But outcomes may be unequal provided that these inequalities are due to choices rather than circumstances. In a socialist society, then, grasshopper’s shivering does not necessarily signal injustice.

It might, however, signal a different moral defect: namely, a breech of community or compassion. Socialists aspire to a social world within which people care about and (when necessary) care for one another. Dramatically different living conditions put this regime of mutual comprehension, concern, and caring in jeopardy. Condemned to the wintry cold, grasshopper would face trials beyond ant’s understanding. The two bugs would come to dwell in different worlds. Whatever fellow-feeling or mutual concern previously marked their relations would vanish, leaving only a gulf of indifference and estrangement. This is no way for socialist comrades to live: not because it would be unjust (by hypothesis, it would not) but because it would be insufficiently fraternal and compassionate. Cohen concludes that “certain inequalities that cannot be forbidden in the name of [justice] should nevertheless be forbidden, in the name of community” (Why Not Socialism? 37). On this line, it would be just, but not justified, for ant to bar his door.

Are we back to the Harrison Bergeron reductio, then? Does socialism implausibly require absolute equality of condition after all? No, for two reasons.