The Aesthetics of Classical Music

Musical aesthetics as a whole seeks to understand the perceived properties of music, in particular those properties that lead to experiences of musical value for the listener. It may also be understood more broadly as essentially synonymous with the philosophy of music, thus including issues of musical ontology, epistemology, ethics, and sociology. A specific area of focus within musical aesthetics is the aesthetics of classical music; it addresses questions relating to the aesthetic properties and aesthetic value of music in the Western classical tradition.

Musical aesthetics as a whole seeks to understand the perceived properties of music, in particular those properties that lead to experiences of musical value for the listener. It may also be understood more broadly as essentially synonymous with the philosophy of music, thus including issues of musical ontology, epistemology, ethics, and sociology. A specific area of focus within musical aesthetics is the aesthetics of classical music; it addresses questions relating to the aesthetic properties and aesthetic value of music in the Western classical tradition.

What aesthetic content does classical music have to offer? Does it consist simply in pleasing patterns, which have no meaning outside of the musical structures themselves? Can it express emotion, feeling, or other kinds of inner states? Does classical music offer insights into life not available through other art forms? Can it possess identifiable meanings, or significant conceptual, historical, or symbolic content? If so, how could this be achieved, given that its materials appear to be non-signifying in nature? These are some of the principal questions that concern the aesthetics of classical music.

After discussion of several important issues relating to classical music as an art form and an overview of influential discussions of the topic prior to the 20th century, this article addresses these principal questions through a discussion of four major topic areas in the aesthetics of classical music: musical understanding, musical form, emotion and expressiveness, and some further types of aesthetic content in classical music.

Table of Contents

- Classical Music as an Art Form

- Historical Discussions

- Understanding

- Form

- Emotion

- Human Experience and Values

- References and Further Reading

1. Classical Music as an Art Form

In the case of music, as in other arts, the term ‘classical’ indicates the presence of an established or long-standing tradition. While the roots of classical music extend back to Gregorian chant, three developments occurring in the 11th century are often regarded as marking the beginning of the classical tradition in western music. These are the developments of polyphony, the principles of order, and the establishment of musical pieces as compositions. The classical tradition is centrally defined by European art music composed during the Common Practice period, which encompasses Baroque, Classical, and Romantic music (roughly 1650-1900). It also includes Medieval, Ars Nova, and Renaissance art music, as well as non-European, 20th century, and contemporary art music that incorporates compositional practices that are recognized as being well-established in western art music. While the vast majority of compositions in Western art music unambiguously fall under the category of ‘classical music’, one can argue that, though there will be no decisive line, certain highly experimental or innovative pieces cannot be apart of an established tradition of composition and thus should not be considered ‘classical’.

In contrast to the aesthetics of popular music, the aesthetics of classical music has traditionally focused on aesthetic content that is strictly musical in nature, excluding any additional content conveyed through words, actions, visual displays, or any other non-musical elements. It has typically limited itself to inquiry into the aesthetic content in musical works that is available from music alone, considered apart from any non-musical elements. Although there are clearly topics of significant interest in the additional aesthetic qualities of classical works that include non-musical elements (whether these be semantic, poetic, dramatic, or dance-related), most philosophers writing about classical music have been unwilling to venture into this territory. The focus on music as such in the aesthetics of classical music is due to the compelling philosophical questions generated by pure or ‘absolute’ music, the complexity involved in considering music in combination with non-musical elements, and a desire to understand the art of music apart from any aesthetic content contributed from other sources. In keeping with the historical focus of the aesthetics of classical music on music as such, this article restricts itself to discussion of aesthetic content that is purely musical in nature and it does not address topics involving the combination of music with other aesthetic elements.

Several features of classical music as an art form play a central role in defining the areas of aesthetic inquiry that pertain to it. Three features in particular deserve attention. These are the unique impact classical music has on our inner experience, its temporal nature, and the central role played by the tradition of tonal harmony, even after its “collapse” at the beginning of the 20th century.

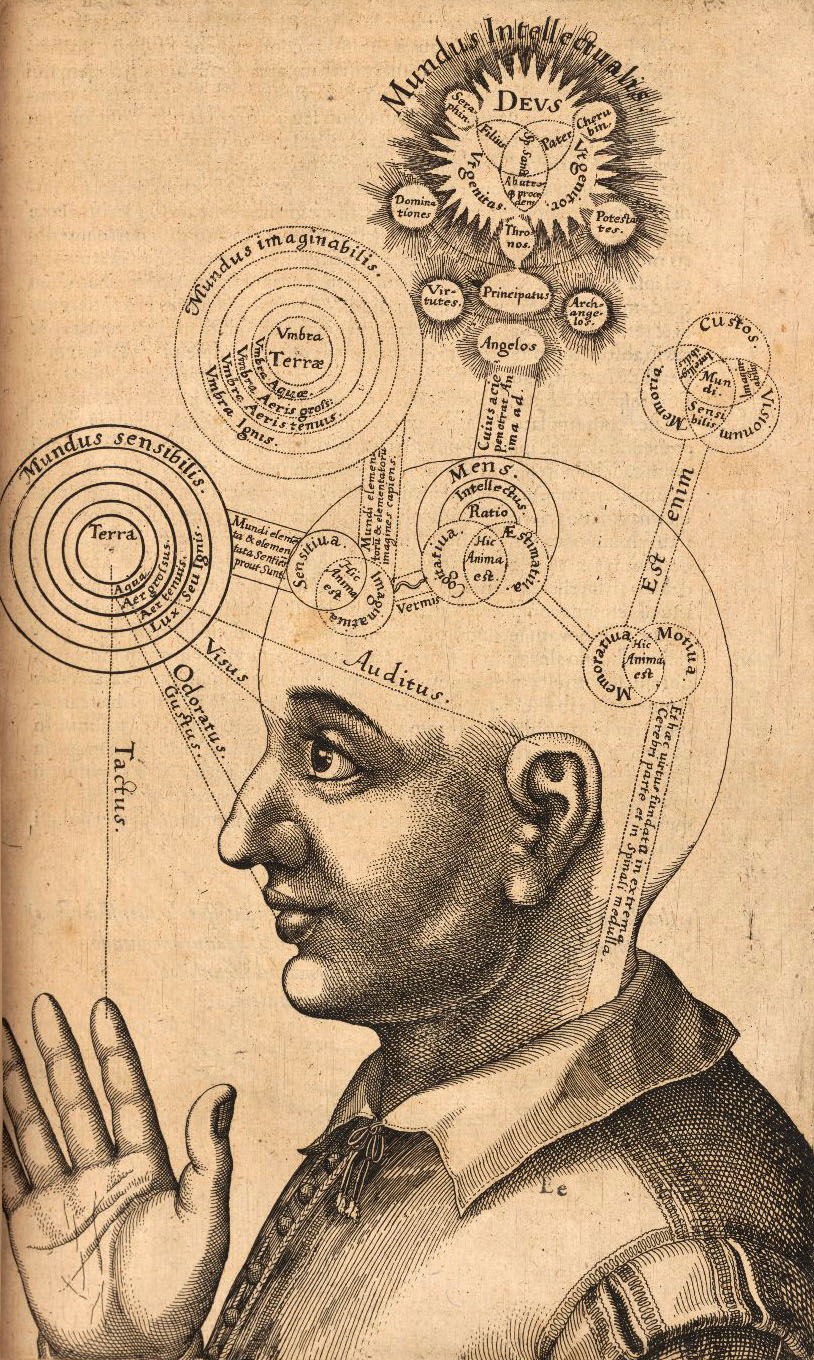

a. Music and Inner Experience

Classical music’s ability to engage and enliven our inner experience is a primary reason why it holds so much philosophical interest. What is it about classical music as an art form that enables it to connect so strongly with our inner life? Part of the answer would seem to lie in the fact that it is an auditory art. The perception of aesthetic content through hearing differs in fundamental ways from the perception of aesthetic content through vision, especially in the case of visual arts that make use of representation. One of the greatest differences between the two modes of artistic perception is that unless we are given rather clear guidelines, we do not interpret musical sounds as representations of objects. The preexisting ability to interpret and assign meanings to visual images does not automatically come into play when we hear musical sounds. It appears that music has the capacity to engage our aesthetic sensibility without also engaging the cognition of objects. This sensibility is linked in complex ways to inner experience, feelings, moods, and emotions.

In Western philosophy, discussion of the special power of music to shape our inner life predates Plato, as evidenced by the lively debates of the pre-Socratics on this topic. Plato himself devotes substantial attention to it in both the Republic and Laws, conceiving of music as an art that can bypass reason and penetrate into our innermost self, impacting the constitution of our character. To use Plato’s terms, music acts as a “charm” on our inner life, shaping this life to its pattern. Classical music in particular stands out among musical cultures for its ability to evoke compelling inner experiences in the listener. Curiously, the power of classical works to evoke such experiences appears to be heightened in many purely instrumental works despite the fact that such pieces possess no readily identifiable meaning.

b. The Temporal Aspect of Music

In addition to its distinctive characteristics as an art form perceived through hearing, music is, of course, always temporal. Many writers, Roger Scruton among them, suggest that music leaves our minds no choice but to move with it when we listen attentively. This activity of the mind is not merely the recognition of new sounds as they occur. The mind moves sympathetically with the motion it perceives in the music. Thus, another important aspect of classical music is that frequently our mental perception of the movement in the music is so strong that we can feel it almost like we feel physical motion.

Our minds also respond to the temporal nature of music in another way. It is the automatic response of the mind to follow the progress of what it hears and assimilate this content into its conception of the piece as a whole. Music’s temporal nature entails that we do not experience the whole work at once or in an order of our choosing, and that consequently the order of presentation is fundamental to our experience of the musical content. In most classical music, and perhaps all art music of the Common Practice period, we perceive purposive and goal-directed movement along with structures and relationships that develop over time, though the scope and complexity of such content varies greatly from piece to piece. As listeners we recognize that an effort has been made to produce an aesthetic value-content, whether formal, expressive, or otherwise, worthy of appreciation or understanding. Due to this recognition, the assumption of an aesthetic attitude is a common practice in listening to classical music and thought to be an important means of enhancing our experience of the music as it unfolds.

c. Classical Music as an Historical Tradition

As an historical tradition, classical music gradually expands its artistic resources, from the practices of medieval polyphony, through the incorporation of new elements in the Renaissance, to the achievement of a conception of music and musical composition that is shared across Europe by the middle of the Baroque. The subsequent development of classical music during the Common Practice period is unique in the way that it preserves a strong continuity in compositional techniques while at the same time evolving continually as an art form. The late works from this period make use of the same basic musical materials (scales and chords) as the early ones: the diatonic scales, triadic functional harmony, primary organization around the dominant-tonic relationship, integration of vertical and horizontal dimensions, and so on. Early works differ from later ones in countless ways, but the fundamental musical materials and relationships do not change until the extended chromaticism of late romantic music begins to dissolve a sense of the tonic altogether. Later works differ from earlier ones primarily through creative innovations that are compatible with existing tonal system made by particular composers and through a gradual exploration and expansion of resources already implied in the tonal system itself. This gradual expansion within the context of a continuous tradition has significant implications for the expressive possibilities classical music possesses as an art form, allowing for the emergence of a repertoire of expressive compositional techniques that grows in effectiveness and scope as it progressively develops the potential that is inherent in tonal harmony.

The diverse compositional approaches developed in classical music in the early part of the 20th century introduce new questions for musical aesthetics. Many aesthetic theories based on analysis of music of the Common Practice period do not apply to compositions based on approaches divergent from those used by tonal harmony. This difference in aesthetic content applies to theories of meaning, form, and expressiveness. Most influential and contemporary philosophers of classical musical aesthetics focus almost exclusively on tonal classical music (including music that achieves a tonal center by means other than tonal harmony, as found in the music of Stravinsky, Debussy, and Bartok). Given that many of these theoretical perspectives do not apply to non-tonal music, the aesthetics of non-tonal classical music is an area that is in need of further development by the discipline.

d. Musical Works and Musical Performances

There are many philosophical questions surrounding the nature and definition of music and the ontological status of works of music. However, because these questions do not apply to classical music in particular, and because the discussion of these topics benefits greatly by comparisons between different musical genres and traditions, they are more appropriately addressed under the philosophy of music or musical aesthetics in general. As a result this entry offers just a brief summary of issues concerning the definition of music, musical ontology, and authentic performance of musical works.

General definitions of music most often focus a demarcation between music and the non-musical (largely due to the musical experimentalism prominent in western art music from the 20th century onward), and on ensuring that the diversity found in the world’s musical traditions is taken into account. These definitional questions are not pertinent to the aesthetics of classical music seeing as they focus on issues involving music outside of the classical tradition.

A similar situation exists with regard to musical ontology, though primary focus is given to works of classical music in some instances. One ontological issue pertaining centrally to classical music concerns the metaphysical nature of a work of music. Do musical works exist? If so, in what sense? With regard to musical ontology a Platonist would hold that a work of classical music is an abstract object, while a nominalist would hold that it must be understood solely in terms of particular objects that relate to it, such as the musical score. In contrast to all of these, anti-realists deny that musical works have any kind of real existence at all, though stopping short of discounting the question altogether, some anti-realists grant musical works a fictional status.

A second issue has to do with what constitutes an authentic performance of a piece. Is it sufficient to perform the right pitches and rhythms in the right order, or is more required to produce an instance of a given work? How essential to authenticity is the use of appropriate period instruments? Is a piano reduction of an orchestral score still an instance of the same work? Debate over these questions centers around which elements must be present in order for a performance to constitute an instance of the work in question. Even if a performance meets the criteria required for authenticity, there is a further question about its reception by the audience. Considering that the sensibilities of listeners continue to change, what is the significance of the fact that contemporary audiences cannot experience works as their original counterparts did?

Influential discussions of musical ontology and authentic performance as they pertain to classical music include Jerrold Levinson’s Music, Art, and Metaphysics, Lydia Goehr’s The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works, and Stephen Davies’ Musical Works and Performances.

2. Historical Discussions

Although discussion of topics relevant to Western musical aesthetics date back to the pre-Socratics, it is not until the 18th century that musical aesthetics takes shape as an inquiry focused on the understanding of perceived properties and capacities of the art of music. Starting with early theorists such as Mattheson and progressing through to thinkers such as Kant and Schopenhauer to later writers such as Gurney, historical discussions of musical aesthetics in Western philosophy are in fact discussions of the aesthetics of classical music. This is for the simple reason that they take music of the classical tradition as their subject matter.

Many of the early discussions of classical musical aesthetics revolve around the question of what music itself is capable of presenting to the listener, with much of the debate centering on the question of how and to what extent music can convey emotional content. German and English discussions of the topic, such as those of Mattheson and Hutcheson, are typically characterized by the view that music either stimulates psychological states directly or arouses them through imitation of ways that emotion is expressed, principally by the human voice. By contrast French theorists during this early period, such as Boyé and Chabanon, oppose the idea that music is capable of expressing emotion on the grounds that it lacks the tools required for successful imitation or representation. These early writers prefigure the debates between expressionist and formalist viewpoints in later discussions of the role of emotion in the experience of classical music (see Lippman for selected excerpts from these authors and further detail on early musical aesthetics).

a. Kant

Following early explorations of the topic the first major contributor to the aesthetics of classical music is Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Judgment. In applying his aesthetic theory to music Kant’s primary concern is with the question of whether, or to what degree, music belongs to the beautiful or to the pleasing arts. Kant maintains that aesthetic judgments consist in feeling disinterested pleasure in perceiving the form of purposiveness in an object, apart from charm, emotion, or any definite concept of what the object ought to be. He further claims that the perception of the form of purposiveness puts the imagination and understanding into harmony such that they are able to freely play with one another. This state of free play, so far as it can be felt in sensation, is the basis of the pleasure that we feel in response to beauty.

Kant considers the possibility that the imagination can apprehend a form in the musical composition which, when compared by reflective judgment to the faculty of referring intuitions to concepts, places the imagination in harmony with the understanding. In music this form, apprehended independently of any conception of an object, is purely a pattern of melodic and harmonic intervals. Harmonious agreement between the imagination and the understanding in the perception of the form of the composition would, provided that this is possible, result in the music being perceived as purposive for reflective judgment. It would also mean that music deserves to be classified among the beautiful arts.

Initially Kant identifies music as an object of pure aesthetic judgments, classifying “all music without words” as a type of free, rather than dependent, beauty. In his more detailed discussion of music in sections 51-54 of his Critique of Judgment, however, Kant seems to vacillate between the possibility that music belongs to the beautiful arts and the possibility that it falls short of providing a formal content suitable for aesthetic judgments and thus is merely a pleasant art. This ultimately leaves the question of which category music belongs to undecided. If music can qualify as beautiful, the composition as a form alone must constitute the object of aesthetic judgment. Factors such as the instruments used to play the composition and the quality of their tone may add charm to the piece and they may even enhance our experience of its beauty, but by themselves such factors do not constitute objects of aesthetic judgment.

While Kant explores the possibility that the composition as an abstract pattern of relationships may present purposive form and thus qualify as beautiful, he appears to conclude that the apprehension of purposive form in music is difficult at best. In the absence of the apprehension of such form, music is limited to the pleasant rather than the beautiful, consisting primarily in a changing play of auditory sensations. In this case, music can produce enjoyment and emotion, but is not a subject for pure judgments of taste. Apart from his enormous influence on the field of aesthetics as a whole, Kant’s writing on music has been influential for its emphasis on purely formal properties and its concomitant rejection of the value of emotion and sensuous qualities to the listening experience. As such, it clearly lays the groundwork for more explicitly formalist approaches in the 19th century.

b. Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer in The World as Will and Representation interpretes ‘will’ as the underlying metaphysical reality, as the thing-in-itself, and grants music the privileged status of presenting it. Departing from Plato and Kant, Schopenhauer denies that the underlying metaphysical reality is rational in nature. Instead, will is a blind urge whose continuous striving has no guiding purpose. Unlike the other arts, whose significance lies in the ability to capture “the permanent essential forms of the world,” thus limiting their reach to interpretations of the phenomenal realm, music expresses the will itself, directly and immediately, speaking the “universal imageless language of the heart.” While in music we experience a direct presentation of the will, nevertheless as thing-in-itself, the musical presentation of will, like will itself, is indescribable.

Despite his allegiance to Kant’s transcendental idealism, Schopenhauer’s aesthetics represents an important departure from Kant. Whereas Kant viewed the aesthetic value of music in purely formal terms as a play of patterns, Schopenhauer advocates that music is valuable for its direct expression of the continuous striving of the will. Thus, the contrasting views of Kant and Schopenhauer prefigure later debates between formalists and expressivists concerning the aesthetic properties of music.

c. Hanslick

In his influential treatise On the Musically Beautiful Eduard Hanslick argues for a strong version of aesthetic formalism that limits aesthetically valuable content to the audible analogue of a moving arabesque or kaleidoscope, differing from these only in that music “manifests itself on an incomparably higher level of ideality” and “presents itself as the direct emanation of an artistically creative spirit.” Hanslick rejects the view that music is capable of expressing emotions, holding instead that music consists purely in tonal forms that develop in time. In doing so he presents an early cognitivist account of emotions, holding that emotions are primarily defined by concepts. He claims that music is incapable of conveying the conceptual content needed to differentiate between specific emotional states. As a result, the aesthetic content of music is limited to a specifically musical kind of beauty that “consists simply and solely of tones and their artistic combination.” His conclusion is that the “representation of a specific feeling or emotional state is not at all among the characteristic powers of music.”

The production of an experience of motion is the aspect of music that is shared with emotion. Through dynamics, tempo, shape, and timbre, music can present auditory instances of qualities that accompany emotions, but no actual emotional content is present, since this would require music to convey concepts: “Music can, in fact, whisper, rage, and rustle. But love and anger occur only within our hearts.” As one might expect given his allegiance to a purely formal conception of musical value, Hanslick also rejects the idea that music as such is suitable for the representation of extramusical content.

d. Gurney

In the latter part of the 19th century Edmund Gurney developed an approach to musical expression based on Darwinian evolutionary theory. Gurney, preceded by Herbert Spencer, postulated a biological origin of music in the impulse to attract and court a mate. According to Gurney, music originates from the capacity that evolved in our ancestors to use sounds to arouse responses from potential mates and rivals. Given that it evolved in this way, music is directly connected to the arousal of our passions. This original connection to the passions and to sexual excitement is fundamental to music in all of its forms. Emotion in classical music is a sublimation of this original sexual excitement. Its origins do not, however, constitute a link between music and extra-musical values or interests. Gurney argues that music offers a profound and entirely self-contained pleasure, whose origins grant it a special connection to our inner experience. Gurney’s work addresses many other fundamental questions in musical aesthetics, including the nature of musical motion, the basic components of musical understanding (which Gurney believed to be melodic forms), musical beauty, and musical value. It is also the inspiration for a recent work by Jerrold Levinson on the nature of musical understanding entitled Music in the Moment.

3. Understanding

Following Gurney’s claims for the role of melodic structures in musical understanding, scholars have generally agreed that an account of the nature of musical understanding must accompany any comprehensive treatment of the aesthetic properties of classical music. Musical understanding in this sense refers to how specific musical structures combine to convey an intelligible sense to the listener. As a result, this establishes a basis upon which to make further claims about the formal or expressive content of music.

a. The Listening Experience

In contemporary discussions there is general consensus that when we experience classical music, we hear the pattern of sounds as an intentional object. That is, we hear the musical work in the form of an unfolding audible musical structure. The term ‘intentional’ in this context signifies that music exists for us in virtue of its being an object of our conscious focus. Hearing patterns of sounds as music is something we contribute as listeners, since it is perfectly possible for someone not familiar with a particular kind of music to fail to grasp its aesthetic qualities. In appreciating music we hear the sounds as musical elements relating to one another within an aesthetic framework as components of a work of art. This audible musical structure together with any additional attendant qualities such as timbre, dynamics and vibrato, is the object of appreciation that produces experiences of aesthetic value. In Values of Art Malcolm Budd attempts a narrower definition that limits the aesthetic content of music to the work’s audible musical structure alone, leaving out of consideration timbral and performance-related aspects. More recently, multiple authors have presented arguments that these attendant qualities are significant aspects of the experience of aesthetic value. Regardless of these particular issues, there is a broad consensus that the experience of aesthetic value in classical music should not be considered separable from the listener’s experience of the audible musical structure of a work. It is this structure, perceived through active listening, that both contains the aesthetic content and produces the experiences of aesthetic value.

In perceiving the audible musical structure, our minds follow the succession of events and we grasp them aesthetically in relation to one another when we listen attentively. This activity of the mind is not merely the recognition of new sounds as they occur, but involves a sense of motion in the music. Given that the unfolding audible structures of classical music do not involve motion in a literal sense, the perception of motion presents a problem for the theorist.

In his pioneering treatise Sound and Symbol, Victor Zuckerkandl identifies our perception of motion as resulting from the directional tendencies present in tonal music. This includes the leading tone seeking to find resolution in or “move to” the tonic. Roger Scruton finds that while this observation is accurate, it does not capture the essence of musical motion. Scruton argues that motion must be understood as part of a system of indispensable metaphors involved in perceiving the music, and further that we perceive musical motion in spatial terms. Malcolm Budd argues that Scruton’s insistence on a spatial conception of musical movement is unnecessary and that a better approach would be to characterize music in terms of a purely temporal Gestalt, limiting music to movement in time and eliminating the need for metaphor. Scruton’s reply is that the concept of merely temporal movement is itself metaphorical in nature and that foundational metaphors such as spatial movement are also indispensable because they connect music to human experience. This allows, he claims, for the development of a complete account of music’s meaning and value.

Another topic of debate concerns the extent to which the perception of larger scale structures plays a role in musical understanding and appreciation. In agreement with the emphasis placed on the value of larger scale formal structures by Heinrich Schenker and Leonard Meyer, Peter Kivy emphasizes the architectonic aspects of the listening experience. He argues that large scale structural patterns and relationships constitute an important aspect of the expressiveness and aesthetic value experienced by the educated listener. In The Aesthetics of Music Roger Scruton also advocates for the importance of these aspects. He finds the comparison between the methods of music composition and architecture to be an apt one, though he rejects the Schenkerian claim that the surface structure of a piece is generated by its underlying large scale plan. In Scruton’s view musical understanding consists in perception of the composer’s development of the fundamental linear and vertical relationships present in tonal music, which he describes as an “order of polyphonic elaboration” that is inherent in the practices of triadic harmony. Inspired by Gurney, Jerrold Levinson disagrees, arguing instead for ‘concatenationism’, the view that basic musical understanding, together with the greater part of music’s aesthetic value, does not require perception of large scale formal relationships and that “the core experience of a piece of music is a matter of how it seems at each point.”

Related to the question of the value of perceiving larger scale formal patterns in classical music is the question of whether formal training or a certain level of education is required for the appreciation of classical music. Though scholars agree that a certain amount of acculturation is required for its understanding and appreciation, there is debate concerning the extent to which education and musical training can enhance the listener’s ability to perceive the aesthetic content of the music. Those such as Kivy who locate the primary aesthetic content of classical music in the musical form and the purely musical relationships that exist within it tend to argue that a higher level of education or acculturation is needed. On the other hand, others such as Levinson locate the primary aesthetic content in expressive qualities and in the way the music unfolds from moment to moment. They vary in their assessment of the aptitude required of the listener depending on their conception of what musical expression consists in and how it occurs.

b. Theories of Musical Meaning

Recognizing that we identify a pattern of sounds as an intentional object aids in understanding how we come to perceive the sounds produced as a form of art. However, this does not address the question of how an unfolding musical structure produces meaningful aesthetic content. An account of musical understanding requires an explanation of how the patterns and relationships present in the musical structure produce meaning for the listener.

In The Language of Music, Deryck Cooke seeks to show that certain recurrent patterns present in the music of the Common Practice period have specific emotional meanings, making it possible to construct a basic emotional vocabulary of classical music that is composed according to the principles of Common Practice tonality. Cooke further extends his analytical approach to defining emotional content contextually. If correct, his insights would establish a basis for understanding the emotional content of most classical music. Malcolm Budd and Roger Scruton have objected to Cooke’s theory on multiple grounds. They argue that it is inappropriate to construe music as a language because music lacks both a syntactic and a semantic structure, and that even if the claim to be a language is taken in a metaphorical sense, the reappearance of similar musical patterns in similar expressive contexts is not a matter of meaning, but of conventionally tested appropriateness to the context in question. Another important objection focuses on Cooke’s claim that composers use music’s vocabulary of emotions to convey the emotions that they felt when composing the work, sometimes labelled the ‘expression-transmission theory’ or simply the ‘expression theory’ of musical expression. Budd points out that by locating the value of the experience in reception of the composer’s emotions, the expression-transmission theory removes the aesthetic value from the work itself, conceiving of music as a tool for arousing the emotions of the composer in the listener. In reality, he argues, we experience aesthetic value primarily in the experience of listening to the music itself. It would misrepresent our motivation for listening to say that experiencing the emotions that the composer experienced could be a substitute for the experience of the specific aesthetic qualities found in a musical piece.

Following Cooke, a comprehensive and detailed attempt to understand how tones and rhythms produce an experience of meaningful content was made by Leonard Meyer in Emotion and Meaning in Music. Meyer, whose basic approach was further developed by Eugene Narmour, makes use of information theory in developing the thesis that a great deal of what we appreciate in classical music is the result of a sense of expectation produced by antecedent-consequent relationships. According to Meyer, a sequence of tones has musical meaning if it points to or sets up the expectation of other tones that will follow. Meyer calls this type of meaning ‘embodied meaning’, as distinguished from ‘designative meaning’ which consists in a culturally established references to some extramusical content. Largely due to his reliance on information theory, Meyer defines embodied meaning purely in terms of expectation. It is generated by directionality inherent in the diatonic scale (leading tone-tonic relationships in melodies and harmonies) as well as by expectation that is built on the listener’s familiarity with traditional forms. One of the most important instances of expectation is the perception of an incomplete pattern, leading to a desire for its fulfillment on the part of the listener.

Finding Meyer’s concept of embodied meaning to be too one dimensional and seeking to restrict musical meaning to the audible musical structure itself (that is, to the exclusion of what Meyer described as designative meanings), Budd offers the concept of ‘intramusical meaning’. This concept, Budd suggests, consists in the ensemble of musical features and relations present in an audible structure as perceived by an educated listener. In developing the concept of intramusical meaning, Budd is seeking to emphasize the abstractness of music as an art form. He wishes to establish that perceiving the audible structure of a work and the relationships that this structure contains, its intramusical meaning, is a necessary precondition for any further interpretation of a musical work. As Budd conceives of it, intramusical meaning is the most basic and fundamental characteristic of a musical piece. Budd points out that Meyer’s concept of embodied meaning is clearly does not account for the diversity of feelings generated in our experience of music of the Common Practice period. Intramusical meaning encompasses all significant relationships perceived by the listener, so it does not restrict musical meaning to a specific process, such as that of antecedent-consequent relationships. At the same time, Budd acknowledges that Meyer’s concept of embodied meaning does account for the production of responses such as anticipation, frustration, confusion, surprise, and satisfaction, with varying degrees of intensity. A potential criticism of Budd’s concept of intramusical meaning is that it places all musical meaning under a single all-encompassing category and gives no account of how specific types of structures or relationships lead to specific musical meanings.

c. Theories of Musical Symbolism

Inspired by Ernst Cassirer’s Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, in Philosophy in a New Key Suzanne Langer interprets musical understanding to consist in grasping a symbolic content rather than in the perception of discrete intramusical meanings. Langer offers a theory of musical works as “unconsummated presentational symbols.” As such, each piece of music symbolizes the form, but not the content, of a feeling. Unlike words, presentational symbols are understood only through seeking to grasp the whole, the elements of which must be interpreted in relation to each other. Pictures are presentational symbols, as are works of music. The main function of musical compositions is to symbolize feelings. Music is an unconsummated presentational symbol because it only reflects the morphology of feeling, not the content of specific feelings. If true, Langer’s theory entails that we can understand a given work as a formal abstraction of an emotional experience. In evaluating Langer’s views, Roger Scruton argues that because Langer’s unconsummated symbols do not have a specific meaning, reflecting instead only the morphology of feelings, her theory reduces to the claim that musical processes have a formal resemblance to emotional processes.

Another significant attempt to speak of music in symbolic terms was made by Nelson Goodman and given further musical focus by Monroe Beardsley. Arguing that works of art symbolize through predication rather than denotation, Goodman develops the concept of ‘exemplification’ to explain artistic expression. An instance of exemplification is one in which a predicate attaches to something which also refers to the predicate, as in a swatch of cloth from a tailor, which “exemplifies only those properties that it both has and refers to.” The difference between everyday instances of exemplification and exemplification in art is that in art the referential component is metaphorical rather than literal in nature. In applying Goodman’s concept of exemplification to music, Beardsley offers the example of a sonata whose first movement has a diffident, indecisive character. Given that it is displayed by the sonata and also plays a significant role in the piece as a whole, diffidence is an instance of musical exemplification.

d. Theories of Musical Syntax and the Influence of the Cognitive Sciences

Several notable authors sought to offer an account of musical meanings by analyzing music in terms of a musical syntax. Influenced by the structuralism of Ferdinand de Saussure, Nicholas Ruwet and Jean-Jacques Nattiez who argue that music does possess a syntax and therefore can be interpreted and understood similarly to any other system of signs. A prominent criticism of this approach argues that such an attempt will necessarily be unsuccessful because unlike the case of natural language, it does not appear to be possible to define musical structures in terms of a generative grammar. Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff seek to address precisely this issue in A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. A key issue here is whether it is possible to establish a relationship between deep structure and surface structure in music by providing transformation rules for the generation of surface structures from deep structures. In seeking to establish that music possesses a generative syntax Lerdahl and Jackendoff put forward the ‘reduction hypothesis,’ which they draw from cognitive science. This hypothesis states that we as listeners seek to organize all musical events within a piece into a “single coherent structure, such that they are heard in a hierarchy of relative importance.” Though the attempt to identify syntactic structures in music has been influential, most contemporary theorists would deny that music possesses a syntax in any robust sense.

The emphasis placed by Lerdahl and Jackendoff on how music is organized by our brains while listening shifts the focus from meaning in the music to the cognitive processes by which we understand it (though of course the two are related and both need to be accounted for). This shift makes salient the importance of supplementing philosophical investigations of musical understanding and experience with scientific approaches. Although this entry does not consider specific scientific investigations into musical cognition, it is important to acknowledge the work in areas related to understanding and experiencing music that is being done in the cognitive sciences of psychology and neuroscience. Seeing as musical understanding and experience necessarily relate to cognitive structures and processes, approaches undertaken within various subdisciplines of psychology and neuroscience offer increasingly illuminating investigations into the topics of musical meaning and musical understanding.

In assessing the potential contribution of these fields, Tom Cochrane argues that studies in psychology and neuroscience can provide additional support for one theory of our experience of music over another, as well as in some cases allow us to reframe and synthesize traditionally distinct positions. He also acknowledges the limitations of many scientific studies, which, he suggests, points to the value of an interdisciplinary collaboration between philosophy and cognitive sciences including psychology and neuroscience. A further consideration in support of scientific investigations of musical experience is the fact that philosophical authors commonly make reference to their own personal experience of music as a partial justification for their views. Scientific research into musical cognition also potentially has value for this reason. It may be a way of providing additional support for an otherwise highly subjective component of philosophical theories.

4. Form

Accounts of understanding classical music address the question of how patterns of sound generate meaning for the listener. As such, they have to do with the unfolding of these patterns in time during the listening experience and with the listener’s perception of relationships between musical ideas in the piece. Insofar as they focus on the process of understanding, they only partially address the more general question of what kind or kinds of aesthetic content a musical structure is capable of conveying. Is the aesthetic content of classical music limited to appreciation of patterns and relationships present in the formal structure, or does the musical form relate in some significant way to our experience outside of music? Is the aesthetic experience of this music primarily or wholly intellectual in nature as the cognitivist would claim, or does the listener experience the content in emotional terms through the music’s expressive qualities? The fact that music unaided by words is generally agreed to possess meaning of some sort, but does not appear to possess adequate tools for either representation or signification makes answering these questions especially challenging.

The question of whether music means or expresses anything beyond itself is present in musical aesthetics from the time of the earliest discussions of the topic in the first half of the 18th century. Kant makes the formalist idea of limiting content to form prominent by virtue of his conception of aesthetic beauty as purposiveness without a purpose, or as the form of purposiveness. Hanslick further develops this train of thought in claiming that the aesthetic content of classical music is best understood through the analogy of a moving arabesque. Meyer emphasizes the fundamental importance of formal structures, though he acknowledges extramusical content as a legitimate aspect of some music. Influential contemporary accounts of the aesthetic value and content of the formal structure as such have been offered by Malcolm Budd, Peter Kivy, and Nick Zangwill. Underlying each of these accounts is the formalist intuition that the aesthetically significant qualities of music as an art form result from appreciation of aspects of the musical structure itself as a structure and that music, as such, has no meaning beyond the patterns and relationships present in it. While Budd ultimately appears to reserve judgment about the possibility that music could possess emotionally expressive or extramusical content in addition to the purely musical content that he advocates for. Kivy and Zangwill take a stronger stance, arguing that aesthetically significant content in music is strictly musical in nature.

a. Music as an Abstract Art

In Values of Art, Malcolm Budd characterizes music as the “art of uninterpreted sounds,” arguing that music is essentially an abstract art and that the essence of music is the audible musical structure perceived by the listener. Budd does not deny that music can contain other elements and serve other purposes. For example, when a musical instrument, passage or motif is used to signify something extramusical, or when a musical work in some fashion represents extramusical things or events, or when music is combined with other art forms. His claim is that such elements in music are not proper to the art; that they are not part of music as such. For Budd, the musical content in music is present in an abstract audible structure whose meaning is not determined by meanings in or references to the external world. In this way, music represents nothing, makes no reference to anything, and is not about anything other than itself. Budd restricts what is essential to understanding music to the perception of the audible structural patterns present in a piece and their musically significant relations with one another. All other content is excluded.

Budd calls this form the ‘musical structure’ of the piece. For Budd, music is abstract in the sense that it does not depend for its success as an art form upon a referential relation to other areas of our experience or knowledge, whether this reference be by means of representation, imitation, signification, or by some other technique that referentially links musical sounds to things in the outside world or our experience. It is important to note that in keeping with the majority of those writing in this area by placing emphasis purely on musical content, referential meanings are not given serious consideration as aesthetically significant to music as an art form. Music may possess a variety of referential meanings, from the imitation of extramusical sounds, to culturally established meanings attached either to specific types of sounds or melodies, to imitations of content supplied by a program or accompanying words. Most writers would argue, however, that such referential meanings are not proper to the aesthetic content of classical music, given that they rely for their specification on extramusical elements such as words and cultural conventions. For Budd, the musical structure alone constitutes all of the musically significant content of the music. Other elements may be added for artistic enhancement. Examples of structural elements as Budd conceives of them would include melody, rhythm, and harmony, as well as other aspects of the music judged by the listener to be musically significant, such as clearly identifiable formal patterns, relations between parts (including contrapuntal motion, imitation, etc.), harmonic texture (polyphonic, homophonic, heterophonic, etc.), variations in the number of parts and in performing forces, and the like. Audible aspects of the music including the type and quality of instrument, the quality of the performer’s technique, and the artistic choices that the performer makes are secondary to what is contained in the music apart from these factors.

In defining music as the art of uninterpreted sounds, Budd locates the strictly musical content of music first and foremost in the listener’s perception of relationships between musical structures. Hearing the music in a work consists in perceiving the relatedness of structural features. Music is an unfolding of patterns and relationships in time. Hearing music as such is primarily a dynamic experience. That is, an experience of the flow of energies generated by the temporal unfolding of pitch relationships and rhythmic patterns.

b. Musical Formalism

The claim that music is fundamentally an abstract art may be taken to mean that music contains nothing other than sounds and their relations to one another. In other words, it may be taken to mean that music possesses only formal content such that any content other than this formal content is of secondary importance and an optional addition on the part of the hearer, and hence, not part of music itself. An account of this sort would allow that musical forms can possess emotional content as an expressive property grasped through intellectual perception and that musical forms can produce an affective state in the listener in response to aesthetically significant qualities such as beauty or impressiveness (as with Gurney). However, it would deny that music expresses emotions in any normal sense of the term. Musical formalism holds instead that all aesthetic content in music is purely musical in nature. For this reason, it also denies that music is capable of conveying human experience or values, as well as any kind of broader conceptual content relating to human life.

Peter Kivy, a prominent advocate of this approach, argues that in essence music is “a quasi-syntactical structure” that is understandable solely in musical terms having “no semantic or representational content, no meaning, making reference to nothing beyond itself.” He offers a sustained argument for this viewpoint in Music Alone and develops his discussion further in New Essays on Musical Understanding. It should be noted that in advocating what he describes as ‘musical purism’, Kivy does acknowledge that music can possess some expressive features, provided that these features are non-representational, non-referential, and possess no meaning other than a purely musical one. Kivy suggests that while music neither expresses emotions nor arouses them in us, it can possess expressive properties through resemblance, much in the same way, to use Kivy’s example, we recognize sadness in the face of a St. Bernard.

A centerpiece of Kivy’s argument is his ‘contour theory’ of musical expressiveness, first articulated in The Corded Shell. Kivy argues that the experience of expressive content in music consists, not in the emotional experience of such content, but instead in the recognition of emotional qualities through a similarity between musical shape and the characteristic shape of utterances or bodily gestures. We make this association, according to Kivy, because we are psychologically determined to animate what we perceive and interpret it in human terms. The perception of emotion in music is thus public and objective in the same way it is in people.

Kivy identifies some instances of expressive content that cannot be explained by his contour model, such as our experience of the respective qualities of the major and minor modes. He argues that these instances, whatever their origin, are established by convention and hence have the same objective character as those resembling human behavioral expressions of emotion. While acknowledging the strength of Kivy’s perspective, Mark DeBellis suggests that an appeal to resemblance via contour lacks explanatory power, since to say that we perceive both music and speech or gestures as having the same expressive quality is merely to restate the problem of expressive character. DeBellis also points to the possibility of music resembling human actions that cause emotion rather resembling the expression of the emotion itself, as in satisfaction resulting from the perception of struggle followed by resolution. He questions whether Kivy’s claims about the conventional nature of the major and minor modes can be verified. More recently Kivy has modified his position to one of “enhanced formalism,” holding that pure instrumental music is a “black box” regarding the question of how it comes to possess expressive properties and suggesting that the important question is instead that of understanding the role that these properties play in the formal structure.

Following a similar conception of music’s aesthetic content to that of Kivy, and in agreement with Scruton concerning the metaphorical nature of our descriptions of musical qualities, Nick Zangwill argues for the ‘aesthetic metaphor thesis’. This thesis holds that, except in exceptional cases, emotion descriptions of music are metaphorical descriptions of music’s aesthetic properties. Thus, just as we say without controversy that a passage is delicate, in the same metaphorical manner we can also describe a musical passage as serene. Zangwill acknowledges that we do have intensely valuable aesthetic responses to some works of music, but denies that these responses are emotional in nature. The mistake, according to Zangwill, is to take our metaphorical descriptions literally and confuse the feelings involved in experiencing music with emotions. In agreement with Kivy, Zangwill holds that absolute music cannot evoke ‘garden variety’ emotions and argues instead that in listening to music, we experience specifically aesthetic feelings which share some, but not all of the features found in actual emotional experiences.

c. Beauty, the Sublime, and Sensuous Pleasure

Regardless of the stance taken on whether or not music is capable of expressing emotions or other types of extramusical content, there is universal agreement among theorists that classical music offers unique and highly valuable experiences of musical beauty. Historically, the predominant tendency has been to limit musical beauty to the perception of relationships existing in the formal structure of the work, excluding its sensuous qualities. The most common type of musical beauty attributed to classical music is found in melody. The great majority of individually identifiable melodies that we describe as beautiful possess certain characteristics that are easily recognizable. These include a predominantly conjunct motion, graceful contours, elegance of design, a duration such that the whole can be grasped in the listener’s immediate awareness, a sense of arrival or return toward the end of the melody, a moderate to slow tempo, and a song-like quality in the production of the sound and phrasing (such as bel canto style, for example). The details of style evolve over time, but these general characteristics hold for beautiful melodies throughout the Common Practice period and beyond, as well as for instances of melodic beauty that predate Common Practice tonality. Musical beauty in the sense of patterns pleasing to the intellect and imagination may also be found in the perception of larger scale musical forms. Assessment of the significance of these vary depending on the weight granted to architectonic features in the musical experience. At the very least, certain readily perceivable formal structures such as those present in canons and harmonic ostinatos can be included uncontroversially in standard aspects of musical beauty in classical music. Well-crafted ‘counterpoint’ is a third commonly identified type of musical beauty. At slower tempos and especially in lower registers counterpoint is also acknowledged by many theorists to contribute to perceptions of musical profundity.

Closely related to musical profundity is experience of the sublime. In classical musical aesthetics, as with other arts, the sublime is usually taken to refer to evocation of that which is beyond human comprehension. In keeping with Edmund Burke’s influential analysis, the experience of sublimity in classical music is most often associated with feelings such as awe, astonishment, obscurity, and terror. Musical passages have been considered to evoke the sublime through qualities. These qualities include complexity, whether of overall design or of interaction between musical elements, emotional expression and mood, which may involve intense conflict or turbulence, but could also be present as transcendence or otherworldliness, and creative power either from an impression of the composer’s creative power in the scope or impressiveness of the work or through qualities evoking creativity in the work itself (as in a fantasia).

In contrast to the traditional focus on formal qualities, classical musicians themselves, as well as contemporary listeners to classical music, would almost universally include sensuous qualities as important contributors to musical beauty and sublimity. Indeed, a primary goal for the classical musician is to develop beauty of tone. Additionally timbres and coloristic effects play an increasingly important role in classical compositions starting in the latter part of the 19th century, as seen in musical impressionism and minimalism, as well as in the expanded palette available through the use of greater and more varied performing forces from the Romantic period onward. For these reasons it seems difficult to deny that tone quality and the listener’s experience of both successive and simultaneous combinations of timbres should be possible objects of musical beauty and contributors to the experience of musical sublimity. In the case of sublimity, dynamics and texture would also seem to have an important role, as would, in some instances, articulation and attack. A further question would be the extent to which virtuosic elements and displays of musical virtuosity by soloists constitute or enhance beauty or sublimity in music. A common analogy notes that such displays are the auditory equivalent of fireworks.

5. Emotion

Can music possess expressive content in a more substantial way than in the intellectual recognition of resemblances to human expressive behavior in purely structural qualities, as the cognitivist would suggest? Theories addressing this question can be classed into several categories, as follows. Transmission-expression theories such as Deryck Cooke’s claim that the emotions experienced in the music are those experienced by the composer. Arousal theories claim that the music’s expressiveness consists in its ability to move the listener to have an affective response. Resemblance theories claim that musical expressiveness lies in perception of a similarity between the way the music sounds and the way emotions feel. Mirroring response theories claim that expressiveness lies in the music itself rather than originating in the composer or being located in the listener. Nevertheless, these theories claim that listeners often mirror the emotional qualities that the music expresses, though their doing so is not required for the music to be considered expressive. Imaginative response theories claim that we experience music as expressive by imagining that the emotions we perceive in it belong to an indeterminate persona (since the music itself cannot be the possessor of emotions). Accordingly, to hear emotion in music is to hear it as the expression of feelings by an imagined individual. A related approach emphasizes the metaphorical nature of expression without attributing it to an imagined persona. Sympathy theories emphasize our sympathetic engagement in the music and corresponding enhanced recognition of its qualities.

Although the literature is less extensive, theorists have also examined the presence and role of moods in classical music. ‘Mood’ here refers to the feeling of a state or states that persist over a significant period of time and have the capacity to color our attitude toward all of the musical content that we hear while they are being felt. It is generally assumed that moods differ from emotions not only in that they apply globally, but also in their lack of an intentional object. Although it is difficult to claim that moods contain much expressive content themselves, they may set the stage for the experience of more specific kinds of expressive content. Thus, a joyous mood might set the stage for feelings of triumphant arrival, a somber one for mourning and loss. Noel Carroll proposes that moods in music can offer a solution to the debate between formalists and arousalists, conceding to the formalist that music lacks the tools to represent the kinds of objects emotions require while granting to the arousalist the point that music can arouse “affective states that are objectless, global, [and] diffuse.” Peter Kivy disagrees, claiming that while there are certainly experiential differences between moods and emotions, they are identical in regard to how music can be expressive of them.

a. Association and Arousal Theories

Leonard Meyer combines his account of musical meaning with a theory of affective arousal. Building on the theory of emotions developed by John Dewey (whose aesthetics offers illuminating applications to classical music even though it does not consider classical music specifically), Meyer claims that emotion is evoked “when a tendency to respond is inhibited.” This situation occurs in classical music in innumerable instances when composers establish expectations, then delay the satisfaction of these expectations, as in delayed arrival on the tonic, or failure to complete a pattern that has been initiated. These examples, and countless others like them found throughout the fabric of classical compositions, trigger an affective response by establishing an expectation of fulfillment, then inhibiting that expectation. Meyer claims that this affective response can be either undifferentiated, in which case only a “feeling tone” is present (perhaps akin to purely musical feelings), or differentiated into a specific emotion by the listener in a process of imaginative association. Meyer’s theory is thus an arousal theory in its conception of affective response and an association theory in its account of the experience of specific emotions by the listener. However, as Malcolm Budd and numerous others have observed, in order to be aesthetically significant expressive content must be a product of properties perceived in the music itself. Consequently, expressive content cannot be the product of an association between the music and some extramusical content that defines or shapes our experience of it.

More recently Jenefer Robinson has advanced another version of the arousal theory, arguing that music has the ability to excite physiological arousal directly in the listener. According to Robinson, the listener attaches an emotional label to the state of arousal after this arousal takes place. Making a claim similar to that of Meyer in his theory of emotional differentiation, this label is governed by the context that the listener brings to the listening experience. Following the contributions of Robinson, many theorists now accept that arousal plays a role in the experience of classical music, even if it is only part of a more complete account. Peter Kivy figures as an exception by taking a formalist point of view, suggesting that to interpret our inner state as an emotional one after the fact is optional at best, and furthermore, is not the type of listening that appreciates what music as an art form has to offer.

b. Resemblance Theories

In his Music and the Emotions, Malcolm Budd reviews and rejects many of the prominent theories of musical expressiveness. In his Values of Art, Budd offers an argument for a “basic and minimal concept” of what the expression of emotion in music consists in. According to Budd, the expression of emotion in music amounts to hearing the music as sounding the way an emotion feels. Thus, the core element in the emotional expressiveness of music is the listener’s perception of a likeness between what is in the music and the experience of a particular emotion. In Budd’s view, this basic “cross-categorical likeness perception” must underlie any account of the expression of emotion in music. However music is expressive of emotion, the expression of emotion must always rely at bottom upon the perception of the music as sounding like the way emotions feel. Budd goes on to identify three likely “accretions” to this “basic and minimal account,” but does not commit himself to any one view. First, the music may induce the feeling whose likeness is perceived. Second, the perception of a likeness to emotional experience may be accompanied by listeners imagining an occurrence of the perceived feeling in themselves. Third, instead of imagining experiencing the feelings that are perceived in the music, the listener may imagine that the music is an instance of these feelings rather than the feelings of any specific individual.

In The Aesthetics of Music Roger Scruton classifies Budd’s idea of a cross-categorical likeness perception, Langer’s conception of music as an unconsummated presentational symbol, and Kivy’s contour theory as versions of what he calls ‘the resemblance theory’. Scruton argues that all versions of the resemblance theory will be unsatisfactory for two reasons. First, resemblance theories confuse expression with the means by which it is achieved (as with other arts such as poetry, music does not resemble what it expresses). Second, if resemblance involves recognizing expression without requiring that we experience something of value as a result of it (as Kivy would have it), then successful expression may occur in an aesthetically uninteresting piece of music and it is unclear why the musical presentation of expression would have any special value.

Approaching the problem of expressiveness from another angle, Stephen Davies endorses a contour model similar to Kivy’s, but also emphasizes the centrality of the listener’s response to the perceived expressive properties. Thus, experiencing expressive content involves a ‘mirroring response’ in which the listener experiences an emotion similar to that perceived in the musical structure, though the music itself is not thought to arouse this emotion directly or in a mechanical way.

In his recent Critique of Pure Music James Young advances versions of both arousal and resemblance theories as components of his anti-formalist position, Arguing in a manner similar to Budd, but in greater detail, he claims that that music arouses emotions through the resemblance the listener perceives between the experience of music and the experience of human behavior expressive of emotions. Identifying this process as the result of a ‘cross-domain mapping,’ Young follows an approach similar to that recommended by Tom Cochrane in drawing on empirical studies of listener responses as well as theories of brain function.

c. The Role Imagination and Metaphor

Jerrold Levinson focuses on the imaginative contribution of the listener in offering an account of hearing music as drama. Heard as drama, music consists in the interplay of forces within a piece, energies or impetuses within the piece whose interaction involves qualities such as tension, suspense, assertion, struggle, and conflict. Levinson suggests that when we hear music as drama, we imagine the dramatic actions and motivations to belong to indeterminate personae or person-like agents. He acknowledges that this way of listening adds an optional layer of content not strictly derivable from the music itself.

Aaron Ridley takes an approach similar to Levinson in regards to the imagination of indeterminate personae, but places special emphasis on the melismatic gesture in classical music as a primary vehicle of emotional expressiveness. Ridley argues that the melismatic gesture “resembles items in the expressive repertoire of extramusical human behavior, either physical or vocal,” thus allowing the music to present states of feeling which the listener experiences through a sympathetic response to the music. Following the contributions of Levinson and Ridley several theorists, Scruton among them, have suggested that the introduction of an imagined persona is unnecessary and that the musical entities themselves qualify as dramatic agents interacting with one another.

Much of western classical music from the Common Practice period can easily be characterized as inherently dramatic in nature, involving development, struggle, and resolution, due to its fundamental reliance on the tonic-dominant relationship. This relationship allows for multiple large and small scale instances of motivic development, of tension and resolution, departure and return, and movement and rest to occur within the context of a single piece. The tension found in the dominant seventh, as well as in other chords that function similarly, places the listener in a state of suspense and instills a desire for resolution. Tonal harmony exploits the dynamic qualities of chords within a given harmonic context to create tension, suspense, expectation, and surprise. It is worth noting that conceiving of music as a dramatic art would seem to shift the emphasis away from the value of a particular content in the music itself and toward the experience of dramatic qualities by the listener. Provided that we give ourselves over to it fully, a highly dramatic work may allow us to experience a form of catharsis and perhaps a state of exhausted repletion following the experiences of tension, suspense, and fulfillment.

Roger Scruton focuses on the listener’s sympathetic participation in the music in his account of musical expressiveness. He begins by suggesting that, because music cannot express exact states of mind, transitive notions of expressiveness give way to an intransitive conception of it. As a result, the import of expression in music lies in the listener’s response. Scruton claims that the listener’s response to expressive music is essentially a sympathetic one, a response to “human life, imagined in the sounds we hear.” For Scruton, the sympathetic response includes not only feelings, but actions and gestures as well. In order to hear music with understanding, we must move with it internally. Ultimately, for Scruton, our sympathetic response, our ‘moving with’ the music, is defined by the fact that music avoids explicit statement, while still inviting the listener to ‘enter into’ its expressive content. The experience of musical expressiveness consists in hearing it as “metaphorical movements in a metaphorical space.” The sounds are heard as figurative life, so that “you are the music while the music lasts.” In addition, though he does not believe it expresses any kind of cognitive content, Scruton suggests that the expressive qualities of a significant musical work can allow us to rehearse emotions that are otherwise very hard to feel.

Like Scruton Christopher Peacocke gives a central place to metaphor in the experience of musical expressiveness. In a recent influential paper, Peacocke suggests that when music is heard as expressing a particular property, some feature of it is heard “metaphorically-as” that property. Offering a non-linguistic account of metaphor informed by current accounts in cognitive science, Peacocke argues that in listening to music metaphor “is exploited in the perception, rather than being represented.” Thus when a piece of music succeeds in expressing a particular property, some of its features are perceived metaphorically-as possessing some of the characteristics of this property. This may occur at a single moment, or through the development of the music over time.

In a reply to Peacocke, Malcolm Budd contrasts his characteristically minimalist account of metaphorical content as the listener capturing some character of the music as he perceives it, with Peacocke’s account of the perceived property as a constituent of the intentional content of the listener’s perception. Budd questions what information a metaphorical-as constituent of a perception carries. He suggests that if it is no information, then the claim of metaphorical-as perception to cognitive status lapses. Kivy also raises questions about Peacocke’s account, asking the normative question of what metaphorical readings are permissible in Peacocke’s sense of metaphorically-as. He worries that it is unclear whether the account places limits on what can be heard metaphorically-as, leaving open the possibility that anything is permissible.

d. The Expression of Negative Emotions

The traditional question of the value of negative emotions in aesthetic experience applies to classical music as it does to the other arts. However, the question involves additional challenges in the case of pure music if one considers such music to be both abstract and highly expressive. In arguing for a specifically musical emotion that is both pleasurable to experience and universal to all aesthetically significant works of music, Gurney sidesteps the issue altogether. Nelson Goodman addresses the question by suggesting that in aesthetic experience “emotions function cognitively,” meaning that we use emotions to understand the aesthetic content of the work. In an influential essay entitled “Music and Negative Emotion” Jerrold Levinson accepts the suggestion made by Goodman and argues that Aristotle’s original claim of catharsis also has substantial merit in the case of classical music. Beyond these he identifies six additional “rewards” that may be associated with listening to music expressive of negative emotions, most having to do with benefits associated with experiencing and understanding emotions, either ours or another’s. Stephen Davies, by contrast, suggests in Musical Meaning and Expression that there is no real difference between our willingness to expose ourselves to negative emotions in music and our willingness to do so in other areas of life, so the question is more about our response to the human condition than it is about listening to music. A related possibility is that negative emotions in music offer a truthful reflection of our experience outside of music, and that we value such music in part because it affirms a reality we experience in our lives.

6. Human Experience and Values

Beyond the claim for emotionally expressive content in music, some writers have suggested that classical music possesses content that reflects aspects of human experience and values that surpass the expression of emotion, mood, and feeling, or the interplay of imagined personae. Wilhelm Dilthey and Jean-Paul Sartre both make such claims for music, and kindred claims can also be found in the writings of a number of contemporary aestheticians. However, while claims for a more significant human content in music resonate with many people, they have found only limited support among theorists because it has proven difficult to sustain an argument for the presence of this kind of content in music alone without tying the aesthetic claims to a larger philosophical framework that itself makes claims about human experience and values.

a. Dilthey and Music as the Expression of Lived Experience

Wilhelm Dilthey offers one of the most suggestive approaches to the expression of content holding a larger human significance in his late hermeneutical writings, especially in his discussion of musical understanding in “The Understanding of Other Persons and Their Manifestations of Life.” Dilthey’s argument for the expression of human experience in music depends upon a specific conception of what artistic expression consists in. Like Hegel, Dilthey holds that the psyche must obtain self-knowledge by objectifying itself. Unlike the literary, dramatic, and visual arts, however, music alone cannot make use of things or images from the shared external world, nor can it make use of the ability of words and images to refer to the inner world of emotions, perceptions, thoughts, and ideas. Instead, Dilthey argues, music transforms lived experience into a form of expression all on its own in a way that that opens up areas of human experience not accessible to the other arts.

The composer does not translate feelings that arose outside of music into musical terms. Rather the composer develops a capacity for specifically musical feelings through immersion in a musical tradition, in this case the tradition of Common Practice tonality together with all of the expressive techniques developed within this framework by individual composers. This capacity allows the composer to transform non-musical experiences into musical ones. Unlike most other expressive arts, music does not achieve its meanings through signification or representation. Instead, the capacity for musical feelings, as developed in relation to a musical tradition, takes the place of the capacity for signification found in language or that of representation found in the visual arts. Every art requires some vehicle or means through which to pursue the goal of appropriating the human world. In the case of music, Dilthey suggests, this vehicle is a capacity for musical feelings developed within a specific cultural tradition.

Expressions of lived experience in music, then, are expressions, not just of the uniquely individual experience of the composer, but of individuality perceived against a particular cultural-historical background. Expressions of lived experience express not only the individuality of the composer’s experience, but also the composer’s experience as it is determined by cultural and historical factors. As Edward Lippman points out, a primary reason why Dilthey is able to develop his argument as he does is that he interprets the arts as a whole in relation to a conception of interconnected cultural systems that are themselves part of the “overall nexus of life.” It is only because classical music consists in a tradition that is interwoven into this nexus that it can transform lived experience into an object of artistic expression.

b. Sartre, Adorno, and Music as a Social Force

Offering a major revision of the theory of music that he presents in The Psychology of the Imagination, Jean-Paul Sartre argues in “The Artist and His Conscience” that rather than consisting in an object of ideal beauty, music instead expresses cultural-historical values. Sartre explores the musical work as a historical and cultural totality, which simultaneously reflects and transcends its time. He identifies music as a “non-signifying art,” one that does not refer beyond itself, but nevertheless possesses a meaning. This meaning cannot be adequately expressed by any system of signs, but instead “is always a matter of a totality, a totality of a person, a milieu, time, or human condition.” Sartre’s focus in this essay is upon the possibility of music as a committed art form, by which he understands an art form that furthers human freedom. As George Bauer points out, for Sartre the goal of the musician is to find a means of “revealing the liberty of the human condition within his compositions–even to the untutored.”