The Evidential Problem of Evil

The evidential problem of evil is the problem of determining whether and, if so, to what extent the existence of evil (or certain instances, kinds, quantities, or distributions of evil) constitutes evidence against the existence of God, that is to say, a being perfect in power, knowledge and goodness. Evidential arguments from evil attempt to show that, once we put aside any evidence there might be in support of the existence of God, it becomes unlikely, if not highly unlikely, that the world was created and is governed by an omnipotent, omniscient, and wholly good being. Such arguments are not to be confused with logical arguments from evil, which have the more ambitious aim of showing that, in a world in which there is evil, it is logically impossible—and not just unlikely—that God exists.

This entry begins by clarifying some important concepts and distinctions associated with the problem of evil, before providing an outline of one of the more forceful and influential evidential arguments developed in contemporary times, namely, the evidential argument advanced by William Rowe. Rowe’s argument has occasioned a range of responses from theists, including the so-called “skeptical theist” critique (according to which God’s ways are too mysterious for us to comprehend) and the construction of various theodicies, that is, explanations as to why God permits evil. These and other responses to the evidential problem of evil are here surveyed and assessed.

Table of Contents

- Background to the Problem of Evil

- William Rowe’s Evidential Argument from Evil

- The Skeptical Theist Response

- Building a Theodicy, or Casting Light on the Ways of God

- Further Responses to the Evidential Problem of Evil

- Conclusion

- References and Further Reading

1. Background to the Problem of Evil

Before delving into the deep and often murky waters of the problem of evil, it will be helpful to provide some philosophical background to this venerable subject. The first and perhaps most important step of this stage-setting process will be to identify and clarify the conception of God that is normally presupposed in contemporary debates (at least within the Anglo-American analytic tradition) on the problem of evil. The next step will involve providing an outline of some important concepts and distinctions, in particular the age-old distinction between “good” and “evil,” and the more recent distinction between the logical problem of evil and the evidential problem of evil.

a. Orthodox Theism

The predominant conception of God within the western world, and hence the kind of deity that is normally the subject of debate in discussions on the problem of evil in most western philosophical circles, is the God of “orthodox theism.” According to orthodox theism, there exists just one God, this God being a person or person-like. The operative notion, however, behind this form of theism is that God is perfect, where to be perfect is to be the greatest being possible or, to borrow Anselm’s well-known phrase, the being than which none greater can be conceived. (Such a conception of God forms the starting-point in what has come to be known as “perfect being theology”; see Morris 1987, 1991, and Rogers 2000). On this view, God, as an absolutely perfect being, must possess the following perfections or great-making qualities:

- omnipotence: This refers to God’s ability to bring about any state of affairs that is logically possible in itself as well as logically consistent with his other essential attributes.

- omniscience: God is omniscient in that he knows all truths or knows all that is logically possible to know.

- perfect goodness: God is the source of moral norms (as in divine command ethics) or always acts in complete accordance with moral norms.

- aseity: God has aseity (literally, being from oneself, a se esse) – that is to say, he is self-existent or ontologically independent, for he does not depend either for his existence or for his characteristics on anything outside himself.

- incorporeality: God has no body; he is a non-physical spirit but is capable of affecting physical things.

- eternity: Traditionally, God is thought to be eternal in an atemporal sense—that is, God is timeless or exists outside of time (a view upheld by Augustine, Boethius, and Aquinas). On an alternative view, God’s eternality is held to be temporal in nature, so that God is everlasting or exists in time, having infinite temporal duration in both of the two temporal directions.

- omnipresence: God is wholly present in all space and time. This is often interpreted metaphorically to mean that God can bring about an event immediately at any place and time, and knows what is happening at every place and time in the same immediate manner.

- perfectly free: God is absolutely free either in the sense that nothing outside him can determine him to perform a particular action, or in the sense that it is always within his power not to do what he does.

- alone worthy of worship and unconditional commitment: God, being the greatest being possible, is the only being fit to be worshipped and the only being to whom one may commit one’s life without reservation.

The God of traditional theism is also typically accorded a further attribute, one that he is thought to possess only contingently:

- creator and sustainer of the world: God brought the (physical and non-physical) world into existence, and also keeps the world and every object within it in existence. Thus, no created thing could exist at a given moment unless it were at that moment held in existence by God. Further, no created thing could have the causal powers and liabilities it has at a given moment unless it were at that moment supplied with those powers and liabilities by God.

According to orthodox theism, God was free not to create a world. In other words, there is at least one possible world in which God creates nothing at all. But then God is a creator only contingently, not necessarily. (For a more comprehensive account of the properties of the God of orthodox theism, see Swinburne 1977, Quinn & Taliaferro 1997: 223-319, and Hoffman & Rosenkrantz 2002.)

b. Good and Evil

Clarifying the underlying conception of God is but the first step in clarifying the nature of the problem of evil. To arrive at a more complete understanding of this vexing problem, it is necessary to unpack further some of its philosophical baggage. I turn, therefore, to some important concepts and distinctions associated with the problem of evil, beginning with the ideas of “good” and “evil.”

The terms “good” and “evil” are, if nothing else, notoriously difficult to define. Some account, however, can be given of these terms as they are employed in discussions of the problem of evil. Beginning with the notion of evil, this is normally given a very wide extension so as to cover everything that is negative and destructive in life. The ambit of evil will therefore include such categories as the bad, the unjust, the immoral, and the painful. An analysis of evil in this broad sense may proceed as follows:

An event may be categorized as evil if it involves any of the following:

- some harm (whether it be minor or great) being done to the physical and/or psychological well-being of a sentient creature;

- the unjust treatment of some sentient creature;

- loss of opportunity resulting from premature death;

- anything that prevents an individual from leading a fulfilling and virtuous life;

- a person doing that which is morally wrong;

- the “privation of good.”

Condition (a) captures what normally falls under the rubric of pain as a physical state (for example, the sensation you feel when you have a toothache or broken jaw) and suffering as a mental state in which we wish that our situation were otherwise (for example, the experience of anxiety or despair). Condition (b) introduces the notion of injustice, so that the prosperity of the wicked, the demise of the virtuous, and the denial of voting rights or employment opportunities to women and blacks would count as evils. The third condition is intended to cover cases of untimely death, that is to say, death not brought about by the ageing process alone. Death of this kind may result in loss of opportunity either in the sense that one is unable to fulfill one’s potential, dreams or goals, or merely in the sense that one is prevented from living out the full term of their natural life. This is partly why we consider it a great evil if an infant were killed after impacting with a train at full speed, even if the infant experienced no pain or suffering in the process. Condition (d) classifies as evil anything that inhibits one from leading a life that is both fulfilling and virtuous – poverty and prostitution would be cases in point. Condition (e) relates evil to immoral choices or acts. And the final condition expresses the idea, prominent in Augustine and Aquinas, that evil is not a substance or entity in its own right, but a privatio boni: the absence or lack of some good power or quality which a thing by its nature ought to possess.

Paralleling the above analysis of evil, the following account of “good” may be offered:

An event may be categorized as good if it involves any of the following:

- some improvement (whether it be minor or great) in the physical and/or psychological well-being of a sentient creature;

- the just treatment of some sentient creature;

- anything that advances the degree of fulfillment and virtue in an individual’s life;

- a person doing that which is morally right;

- the optimal functioning of some person or thing, so that it does not lack the full measure of being and goodness that ought to belong to it.

Turning to the many varieties of evil, the following have become standard in the literature:

Moral evil. This is evil that results from the misuse of free will on the part of some moral agent in such a way that the agent thereby becomes morally blameworthy for the resultant evil. Moral evil therefore includes specific acts of intentional wrongdoing such as lying and murdering, as well as defects in character such as dishonesty and greed.

Natural evil. In contrast to moral evil, natural evil is evil that results from the operation of natural processes, in which case no human being can be held morally accountable for the resultant evil. Classic examples of natural evil are natural disasters such as cyclones and earthquakes that result in enormous suffering and loss of life, illnesses such as leukemia and Alzheimer’s, and disabilities such as blindness and deafness.

An important qualification, however, must be made at this point. A great deal of what normally passes as natural evil is brought about by human wrongdoing or negligence. For example, lung cancer may be caused by heavy smoking; the loss of life occasioned by some earthquakes may be largely due to irresponsible city planners locating their creations on faults that will ultimately heave and split; and some droughts and floods may have been prevented if not for the careless way we have treated our planet. As it is the misuse of free will that has caused these evils or contributed to their occurrence, it seems best to regard them as moral evils and not natural evils. In the present work, therefore, a natural evil will be defined as an evil resulting solely or chiefly from the operation of the laws of nature. Alternatively, and perhaps more precisely, an evil will be deemed a natural evil only if no non-divine agent can be held morally responsible for its occurrence. Thus, a flood caused by human pollution of the environment will be categorized a natural evil as long as the agents involved could not be held morally responsible for the resultant evil, which would be the case if, for instance, they could not reasonably be expected to have foreseen the consequences of their behavior.

A further category of evil that has recently played an important role in discussions on the problem of evil is horrendous evil. This may be defined, following Marilyn Adams (1999: 26), as evil “the participation in which (that is, the doing or suffering of which) constitutes prima facie reason to doubt whether the participant’s life could (given their inclusion in it) be a great good to him/her on the whole.” As examples of such evil, Adams lists “the rape of a woman and axing off of her arms, psycho-physical torture whose ultimate goal is the disintegration of personality, betrayal of one’s deepest loyalties, child abuse of the sort described by Ivan Karamazov, child pornography, parental incest, slow death by starvation, the explosion of nuclear bombs over populated areas” (p.26).

A horrendous evil, it may be noted, may be either a moral evil (for example, the Holocaust of 1939-45) or a natural evil (for example, the Lisbon earthquake of 1755). It is also important to note that it is the notion of a “horrendous moral evil” that comports with the current, everyday use of “evil” by English speakers. When we ordinarily employ the word “evil” today we do not intend to pick out something that is merely bad or very wrong (for example, a burglary), nor do we intend to refer to the death and destruction brought about by purely natural processes (we do not, for example, think of the 2004 Asian tsunami disaster as something that was “evil”). Instead, the word “evil” is reserved in common usage for events and people that have an especially horrific moral quality or character.

Clearly, the problem of evil is at its most difficult when stated in terms of horrendous evil (whether of the moral or natural variety), and as will be seen in Section II below, this is precisely how William Rowe’s statement of the evidential problem of evil is formulated.

Finally, these notions of good and evil indicate that the problem of evil is intimately tied to ethics. One’s underlying ethical theory may have a bearing on one’s approach to the problem of evil in at least two ways.

Firstly, one who accepts either a divine command theory of ethics or non-realism in ethics is in no position to raise the problem of evil, that is, to offer the existence of evil as at least a prima facie good reason for rejecting theism. This is because a divine command theory, in taking morality to be dependent upon the will of God, already assumes the truth of that which is in dispute, namely, the existence of God (see Brown 1967). On the other hand, non-realist ethical theories, such as moral subjectivism and error-theories of ethics, hold that there are no objectively true moral judgments. But then a non-theist who also happens to be a non-realist in ethics cannot help herself to some of the central premises found in evidential arguments from evil (such as “If there were a perfectly good God, he would want a world with no horrific evil in it”), as these purport to be objectively true moral judgments (see Nelson 1991). This is not to say, however, that atheologians such as David Hume, Bertrand Russell and J.L. Mackie, each of whom supported non-realism in ethics, were contradicting their own meta-ethics when raising arguments from evil – at least if their aim was only to show up a contradiction in the theist’s set of beliefs.

Secondly, the particular normative ethical theory one adopts (for example, consequentialism, deontology, virtue ethics) may influence the way in which one formulates or responds to an argument from evil. Indeed, some have gone so far as to claim that evidential arguments from evil usually presuppose the truth of consequentialism (see, for example, Reitan 2000). Even if this is not so, it seems that the adoption of a particular theory in normative ethics may render the problem of evil easier or harder, or at least delimit the range of solutions available. (For an excellent account of the difficulties faced by theists in relation to the problem of evil when the ethical framework is restricted to deontology, see McNaughton 1994.)

c. Versions of the Problem of Evil

The problem of evil may be described as the problem of reconciling belief in God with the existence of evil. But the problem of evil, like evil itself, has many faces. It may, for example, be expressed either as an experiential problem or as a theoretical problem. In the former case, the problem is the difficulty of adopting or maintaining an attitude of love and trust toward God when confronted by evil that is deeply perplexing and disturbing. Alvin Plantinga (1977: 63-64) provides an eloquent account of this problem:

The theist may find a religious problem in evil; in the presence of his own suffering or that of someone near to him he may find it difficult to maintain what he takes to be the proper attitude towards God. Faced with great personal suffering or misfortune, he may be tempted to rebel against God, to shake his fist in God’s face, or even to give up belief in God altogether… Such a problem calls, not for philosophical enlightenment, but for pastoral care. (emphasis in the original)

By contrast, the theoretical problem of evil is the purely “intellectual” matter of determining what impact, if any, the existence of evil has on the truth-value or the epistemic status of theistic belief. To be sure, these two problems are interconnected – theoretical considerations, for example, may color one’s actual experience of evil, as happens when suffering that is better comprehended becomes easier to bear. In this article, however, the focus will be exclusively on the theoretical dimension. This aspect of the problem of evil comes in two broad varieties: the logical problem and the evidential problem.

The logical version of the problem of evil (also known as the a priori version and the deductive version) is the problem of removing an alleged logical inconsistency between certain claims about God and certain claims about evil. J.L. Mackie (1955: 200) provides a succinct statement of this problem:

In its simplest form the problem is this: God is omnipotent; God is wholly good; and yet evil exists. There seems to be some contradiction between these three propositions, so that if any two of them were true the third would be false. But at the same time all three are essential parts of most theological positions: the theologian, it seems, at once must adhere and cannot consistently adhere to all three. (emphases in the original)

In a similar vein, H.J. McCloskey (1960: 97) frames the problem of evil as follows:

Evil is a problem for the theist in that a contradiction is involved in the fact of evil, on the one hand, and the belief in the omnipotence and perfection of God on the other. (emphasis mine)

Atheologians like Mackie and McCloskey, in maintaining that the logical problem of evil provides conclusive evidence against theism, are claiming that theists are committed to an internally inconsistent set of beliefs and hence that theism is necessarily false. More precisely, it is claimed that theists commonly accept the following propositions:

- God exists

- God is omnipotent

- God is omniscient

- God is perfectly good

- Evil exists.

Propositions (11)-(14) form an essential part of the orthodox conception of God, as this has been explicated in Section 1 above. But theists typically believe that the world contains evil. The charge, then, is that this commitment to (15) is somehow incompatible with the theist’s commitment to (11)-(14). Of course, (15) can be specified in a number of ways – for example, (15) may refer to the existence of any evil at all, or a certain amount of evil, or particular kinds of evil, or some perplexing distributions of evil. In each case, a different version of the logical problem of evil, and hence a distinct charge of logical incompatibility, will be generated.

The alleged incompatibility, however, is not obvious or explicit. Rather, the claim is that propositions (11)-(15) are implicitly contradictory, where a set S of propositions is implicitly contradictory if there is a necessary proposition p such that the conjunction of p with S constitutes a formally contradictory set. Those who advance logical arguments from evil must therefore add one or more necessary truths to the above set of five propositions in order to generate the fatal contradiction. By way of illustration, consider the following additional propositions that may be offered:

- A perfectly good being would want to prevent all evils.

- An omniscient being knows every way in which evils can come into existence.

- An omnipotent being who knows every way in which an evil can come into existence has the power to prevent that evil from coming into existence.

- A being who knows every way in which an evil can come into existence, who is able to prevent that evil from coming into existence, and who wants to do so, would prevent the existence of that evil.

From this set of auxiliary propositions, it clearly follows that

- If there exists an omnipotent, omniscient, and perfectly good being, then no evil exists.

It is not difficult to see how the addition of (16)-(20) to (11)-(15) will yield an explicit contradiction, namely,

- Evil exists and evil does not exist.

If such an argument is sound, theism will not so much lack evidential support, but would rather be, as Mackie (1955: 200) puts it, “positively irrational.” For more discussion, see the article The Logical Problem of Evil.

The subject of this article, however, is the evidential version of the problem of evil (also called the a posteriori version and the inductive version), which seeks to show that the existence evil, although logically consistent with the existence of God, counts against the truth of theism. As with the logical problem, evidential formulations may be based on the sheer existence of evil, or certain instances, types, amounts, or distributions of evil. Evidential arguments from evil may also be classified according to whether they employ (i) a direct inductive approach, which aims at showing that evil counts against theism, but without comparing theism to some alternative hypothesis; or (ii) an indirect inductive approach, which attempts to show that some significant set of facts about evil counts against theism, and it does this by identifying an alternative hypothesis that explains these facts far more adequately than the theistic hypothesis. The former strategy, as will be seen in Section II, is employed by William Rowe, while the latter strategy is exemplified best in Paul Draper’s 1989 paper, “Pain and Pleasure: An Evidential Problem for Theists”. (A useful taxonomy of evidential arguments from evil can be found in Russell 1996: 194 and Peterson 1998: 23-27, 69-72.)

Evidential arguments purport to show that evil counts against theism in the sense that the existence of evil lowers the probability that God exists. The strategy here is to begin by putting aside any positive evidence we might think there is in support of theism (for example, the fine-tuning argument) as well as any negative evidence we might think there is against theism (that is, any negative evidence other than the evidence of evil). We therefore begin with a “level playing field” by setting the probability of God’s existing at 0.5 and the probability of God’s not existing at 0.5 (compare Rowe 1996: 265-66; it is worth noting, however, that this “level playing field” assumption is not entirely uncontroversial: see, for example, the objections raised by Jordan 2001 and Otte 2002: 167-68). The aim is to then determine what happens to the probability value of “God exists” once we consider the evidence generated by our observations of the various evils in our world. The central question, therefore, is: Grounds for belief in God aside, does evil render the truth of atheism more likely than the truth of theism? (A recent debate on the evidential problem of evil was couched in such terms: see Rowe 2001a: 124-25.) Proponents of evidential arguments are therefore not claiming that, even if we take into account any positive reasons there are in support of theism, the evidence of evil still manages to lower the probability of God’s existence. They are only making the weaker claim that, if we temporarily set aside such positive reasons, then it can be shown that the evils that occur in our world push the probability of God’s existence significantly downward.

But if evil counts against theism by driving down the probability value of “God exists” then evil constitutes evidence against the existence of God. Evidential arguments, therefore, claim that there are certain facts about evil that cannot be adequately explained on a theistic account of the world. Theism is thus treated as a large-scale hypothesis or explanatory theory which aims to make sense of some pertinent facts, and to the extent that it fails to do so it is disconfirmed.

In evidential arguments, however, the evidence only probabilifies its conclusion, rather than conclusively verifying it. The probabilistic nature of such arguments manifests itself in the form of a premise to the effect that “It is probably the case that some instance (or type, or amount, or pattern) of evil E is gratuitous.” This probability judgment usually rests on the claim that, even after careful reflection, we can see no good reason for God’s permission of E. The inference from this claim to the judgment that there exists gratuitous evil is inductive in nature, and it is this inductive step that sets the evidential argument apart from the logical argument.

2. William Rowe’s Evidential Argument from Evil

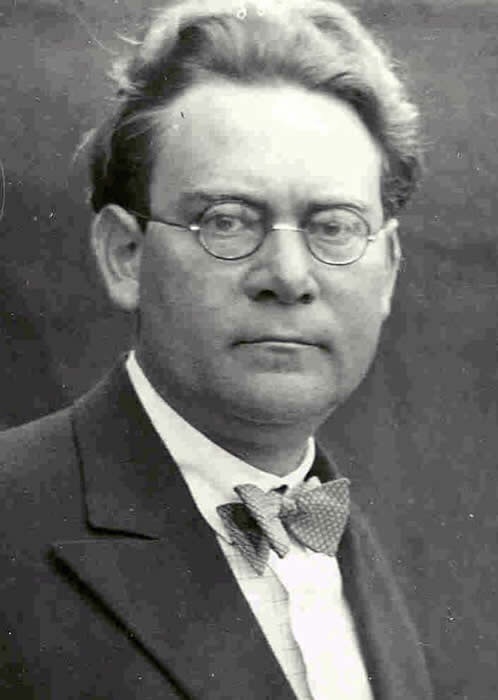

Evidential arguments from evil seek to show that the presence of evil in the world inductively supports or makes likely the claim that God (or, more precisely, the God of orthodox theism) does not exist. A variety of evidential arguments have been formulated in recent years, but here I will concentrate on one very influential formulation, namely, that provided by William Rowe. Rowe’s version of the evidential argument has received much attention since its formal inception in 1978, for it is often considered to be the most cogent presentation of the evidential problem of evil. James Sennett (1993: 220), for example, views Rowe’s argument as “the clearest, most easily understood, and most intuitively appealing of those available.” Terry Christlieb (1992: 47), likewise, thinks of Rowe’s argument as “the strongest sort of evidential argument, the sort that has the best chance of success.” It is important to note, however, that Rowe’s thinking on the evidential problem of evil has developed in significant ways since his earliest writings on the subject, and two (if not three) distinct evidential arguments can be identified in his work. Here I will only discuss that version of Rowe’s argument that received its first full-length formulation in Rowe (1978) and, most famously, in Rowe (1979), and was successively refined in the light of criticisms in Rowe (1986), (1988), (1991), and (1995), before being abandoned in favour of a quite different evidential argument in Rowe (1996).

a. An Outline of Rowe’s Argument

In presenting his evidential argument from evil in his justly celebrated 1979 paper, “The Problem of Evil and Some Varieties of Atheism”, Rowe thinks it best to focus on a particular kind of evil that is found in our world in abundance. He therefore selects “intense human and animal suffering” as this occurs on a daily basis, is in great plenitude in our world, and is a clear case of evil. More precisely, it is a case of intrinsic evil: it is bad in and of itself, even though it sometimes is part of, or leads to, some good state of affairs (Rowe 1979: 335). Rowe then proceeds to state his argument for atheism as follows:

- There exist instances of intense suffering which an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

- An omniscient, wholly good being would prevent the occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

- (Therefore) There does not exist an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good being. (Rowe 1979: 336)

This argument, as Rowe points out, is clearly valid, and so if there are rational grounds for accepting its premises, to that extent there are rational grounds for accepting the conclusion, that is to say, atheism.

b. The Theological Premise

The second premise is sometimes called “the theological premise” as it expresses a belief about what God as a perfectly good being would do under certain circumstances. In particular, this premise states that if such a being knew of some intense suffering that was about to take place and was in a position to prevent its occurrence, then it would prevent it unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. Put otherwise, an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good God would not permit any gratuitous evil, evil that is (roughly speaking) avoidable, pointless, or unnecessary with respect to the fulfillment of God’s purposes.

Rowe takes the theological premise to be the least controversial aspect of his argument. And the consensus seems to be that Rowe is right – the theological premise, or a version thereof that is immune from some minor infelicities in the original formulation, is usually thought to be indisputable, self-evident, necessarily true, or something of that ilk. The intuition here, as the Howard-Snyders (1999: 115) explain, is that “on the face of it, the idea that God may well permit gratuitous evil is absurd. After all, if God can get what He wants without permitting some particular horror (or anything comparably bad), why on earth would He permit it?”

An increasing number of theists, however, are beginning to question Rowe’s theological premise. This way of responding to the evidential problem of evil has been described by Rowe as “radical, if not revolutionary” (1991: 79), but it is viewed by many theists as the only way to remain faithful to the common human experience of evil, according to which utterly gratuitous evil not only exists but is abundant. In particular, some members of the currently popular movement known as open theism have rallied behind the idea that the theistic worldview is not only compatible with, but requires or demands, the possibility that there is gratuitous evil (for the movement’s “manifesto,” see Pinnock et al. 1994; see also Sanders 1998, Boyd 2000, and Hasker 2004).

Although open theists accept the orthodox conception of God, as delineated in Section 1.a above, they offer a distinct account of some of the properties that are constitutive of the orthodox God. Most importantly, open theists interpret God’s omniscience in such a way that it does not include either foreknowledge (or, more specifically, knowledge of what free agents other than God will do) or middle knowledge (that is, knowledge of what every possible free creature would freely choose to do in any possible situation in which that creature might find itself). This view is usually contrasted with two other forms of orthodox theism: Molinism (named after the sixteenth-century Jesuit theologian Luis de Molina, who developed the theory of middle knowledge), according to which divine omniscience encompasses both foreknowledge and middle knowledge; and Calvinism or theological determinism, according to which God determines or predestines all that happens, thus leaving us with either no morally relevant free will at all (hard determinism) or free will of the compatibilist sort only (soft determinism).

It is often thought that the Molinist and Calvinist grant God greater providential control over the world than does the open theist. For according to the latter but not the former, the future is to some degree open-ended in that not even God can know exactly how it will turn out, given that he has created a world in which there are agents with libertarian free will and, perhaps, indeterminate natural processes. God therefore runs the risk that his creation will come to be infested with gratuitous evils, that is to say, evils he has not intended, decreed, planned for, or even permitted for the sake of some greater good. Open theists, however, argue that this risk is kept in check by God’s adoption of various general strategies by which he governs the world. God may, for example, set out to create a world in which there are creatures who have the opportunity to freely choose their destiny, but he would then ensure that adequate recompense is offered (perhaps in an afterlife) to those whose lives are ruined (through no fault of their own) by the misuse of others’ freedom (for example, a child that is raped and murdered). Nevertheless, in creating creatures with (libertarian) free will and by infusing the natural order with a degree of indeterminacy, God relinquishes exhaustive knowledge and complete control of all history. The open theist therefore encourages the rejection of what has been called “meticulous providence” (Peterson 1982: chs 4 & 5) or “the blueprint worldview” (Boyd 2003: ch.2), the view that the world was created according to a detailed divine blueprint which assigns a specific divine reason for every occurrence in history. In place of this view, the open theist presents us with a God who is a risk-taker, a God who gives up meticulous control of everything that happens, thus opening himself up to the genuine possibility of failure and disappointment – that is to say, to the possibility of gratuitous evil.

Open theism has sparked much heated debate and has been attacked from many quarters. Considered, however, as a response to Rowe’s theological premise, open theism’s prospects seem dim. The problem here, as critics have frequently pointed out, is that the open view of God tends to diminish one’s confidence in God’s ability to ensure that his purposes for an individual’s life, or for world history, will be accomplished (see, for example, Ware 2000, Ascol 2001: 176-80). The worry is that if, as open theists claim, God does not exercise sovereign control over the world and the direction of human history is open-ended, then it seems that the world is left to the mercy of Tyche or Fortuna, and we are therefore left with no assurance that God’s plan for the world and for us will succeed. Consider, for example, Eleonore Stump’s rhetorical questions, put in response to the idea of a “God of chance” advocated in van Inwagen (1988): “Could one trust such a God with one’s child, one’s life? Could one say, as the Psalmist does, “I will both lay me down in peace and sleep, for thou, Lord, only makest me dwell in safety’?” (1997: 466, quoting from Psalm 4:8). The answer may in large part depend on the degree to which the world is thought to be imbued with indeterminacy or chance.

If, for example, the open theist view introduces a high level of chance into God’s creation, this would raise the suspicion that the open view reflects an excessively deistic conception of God’s relation to the world. Deism is popularly thought of as the view that a supreme being created the world but then, like an absentee landlord, left it to run on its own accord. Deists, therefore, are often accused of postulating a remote and indifferent God, one who does not exercise providential care over his creation. Such a deity, it might be objected, resembles the open theist’s God of chance. The objection, in other words, is that open theists postulate a dark and risky universe subject to the forces of blind chance, and that it is difficult to imagine a personal God—that is, a God who seeks to be personally related to us and hence wants us to develop attitudes of love and trust towards him—providing us with such a habitat. To paraphrase Einstein, God does not play dice with our lives.

This, however, need not mean that God does not play dice at all. It is not impossible, in other words, to accommodate chance within a theistic world-view. To see this, consider a particular instance of moral evil: the rape and murder of a little girl. It seems plausible that no explanation is available as to why God would permit this specific evil (or, more precisely, why God would permit this girl to suffer then and there and in that way), since any such explanation that is offered will inevitably recapitulate the explanation offered for at least one of the major evil-kinds that subsumes the particular evil in question (for example, the class of moral evils). It is therefore unreasonable to request a reason (even a possible reason) for God’s permission of a particular event that is specific to this event and that goes beyond some general policy or plan God might have for permitting events of that kind. If this correct, then there is room for theists to accept the view that at least some evils are chancy or gratuitous in the sense that there is no specific reason as to why these evils are permitted by God. However, this kind of commitment to gratuitous evil is entirely innocuous for proponents of Rowe’s theological premise. For one can simply modify this premise so that it ranges either over particular instances of evil or (to accommodate cases where particular evils admit of no divine justification) over broadly defined evils or evil-kinds under which the relevant particular evils can be subsumed. And so a world created by God may be replete with gratuitous evil, as open theists imagine, but that need not present a problem for Rowe.

(For a different line of argument in support of the compatibility of theism and gratuitous evil, see Hasker (2004: chs 4 & 5), who argues that the consequences for morality would be disastrous if we took Rowe’s theological premise to be true. For criticisms of this view, see Rowe (1991: 79-86), Chrzan (1994), O’Connor (1998: 53-70), and Daniel and Frances Howard-Snyder (1999: 119-27).)

c. The Factual Premise

Criticisms of Rowe’s argument tend to focus on its first premise, sometimes dubbed “the factual premise,” as it purports to state a fact about the world. Briefly put, the fact in question is that there exist instances of intense suffering which are gratuitous or pointless. As indicated above, an instance of suffering is gratuitous, according to Rowe, if an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented it without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. A gratuitous evil, in this sense, is a state of affairs that is not (logically) necessary to the attainment of a greater good or to the prevention of an evil at least as bad.

i Rowe’s Case in Support of the Factual Premise

Rowe builds his case in support of the factual premise by appealing to particular instances of human and animal suffering, such as the following:

E1: the case of Bambi

“In some distant forest lightning strikes a dead tree, resulting in a forest fire. In the fire a fawn is trapped, horribly burned, and lies in terrible agony for several days before death relieves its suffering” (Rowe 1979: 337).

Although this is presented as a hypothetical event, Rowe takes it to be “a familiar sort of tragedy, played not infrequently on the stage of nature” (1988: 119).

E2: the case of Sue

This is an actual event in which a five-year-old girl in Flint, Michigan was severely beaten, raped and then strangled to death early on New Year’s Day in 1986. The case was introduced by Bruce Russell (1989: 123), whose account of it, drawn from a report in the Detroit Free Press of January 3 1986, runs as follows:

The girl’s mother was living with her boyfriend, another man who was unemployed, her two children, and her 9-month old infant fathered by the boyfriend. On New Year’s Eve all three adults were drinking at a bar near the woman’s home. The boyfriend had been taking drugs and drinking heavily. He was asked to leave the bar at 8:00 p.m. After several reappearances he finally stayed away for good at about 9:30 p.m. The woman and the unemployed man remained at the bar until 2:00 a.m. at which time the woman went home and the man to a party at a neighbor’s home. Perhaps out of jealousy, the boyfriend attacked the woman when she walked into the house. Her brother was there and broke up the fight by hitting the boyfriend who was passed out and slumped over a table when the brother left. Later the boyfriend attacked the woman again, and this time she knocked him unconscious. After checking the children, she went to bed. Later the woman’s 5-year old girl went downstairs to go to the bathroom. The unemployed man returned from the party at 3:45 a.m. and found the 5-year old dead. She had been raped, severely beaten over most of her body and strangled to death by the boyfriend.

Following Rowe (1988: 120), the case of the fawn will be referred to as “E1”, and the case of the little girl as “E2”. Further, following William Alston’s (1991: 32) practice, the fawn will be named “Bambi” and the little girl “Sue”.

Rowe (1996: 264) states that, in choosing to focus on E1 and E2, he is “trying to pose a serious difficulty for the theist by picking a difficult case of natural evil, E1 (Bambi), and a difficult case of moral evil, E2 (Sue).” Rowe, then, is attempting to state the evidential argument in the strongest possible terms. As one commentator has put it, “if these cases of evil [E1 and E2] are not evidence against theism, then none are” (Christlieb 1992: 47). However, Rowe’s almost exclusive preoccupation with these two instances of suffering must be placed within the context of his belief (as expressed in, for example, 1979: 337-38) that even if we discovered that God could not have eliminated E1 and E2 without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse, it would still be unreasonable to believe this of all cases of horrendous evil occurring daily in our world. E1 and E2 are thus best viewed as representative of a particular class of evil which poses a specific problem for theistic belief. This problem is expressed by Rowe in the following way:

(P) No good state of affairs we know of is such that an omnipotent, omniscient being’s obtaining it would morally justify that being’s permitting E1 or E2. Therefore,

(Q) It is likely that no good state of affairs is such that an omnipotent, omniscient being’s obtaining it would morally justify that being in permitting E1 or E2.

P states that no good we know of justifies God in permitting E1 and E2. From this it is inferred that Q is likely to be true, or that probably there are no goods which justify God in permitting E1 and E2. Q, of course, corresponds to the factual premise of Rowe’s argument. Thus, Rowe attempts to establish the truth of the factual premise by appealing to P.

ii. The Inference from P to Q

At least one question to be addressed when considering this inference is: What exactly do P and Q assert? Beginning with P, the central notion here is “a good state of affairs we know of.” But what is it to know of a good state of affairs? According to Rowe (1988: 123), to know of a good state of affairs is to (a) conceive of that state of affairs, and (b) recognize that it is intrinsically good (examples of states that are intrinsically good include pleasure, happiness, love, and the exercise of virtue). Rowe (1996: 264) therefore instructs us to not limit the set of goods we know of to goods that we know have occurred in the past or to goods that we know will occur in the future. The set of goods we know of must also include goods that we have some grasp of, even if we do not know whether they have occurred or ever will occur. For example, such a good, in the case of Sue, may consist of the experience of eternal bliss in the hereafter. Even though we lack a clear grasp of what this good involves, and even though we cannot be sure that such a good will ever obtain, we do well to include this good amongst the goods we know of. A good that we know of, however, cannot justify God in permitting E1 or E2 unless that good is actualized at some time.

On what grounds does Rowe think that P is true? Rowe (1988: 120) states that “we have good reason to believe that no good state of affairs we know of would justify an omnipotent, omniscient being in permitting either E1 or E2” (emphasis his). The good reason in question consists of the fact that the good states of affairs we know of, when reflecting on them, meet one or both of the following conditions: either an omnipotent being could obtain them without having to permit E1 or E2, or obtaining them would not morally justify that being in permitting E1 or E2 (Rowe 1988: 121, 123; 1991: 72).

This brings us, finally, to Rowe’s inference from P to Q. This is, of course, an inductive inference. Rowe does not claim to know or be able to prove that cases of intense suffering such as the fawn’s are indeed pointless. For as he acknowledges, it is quite possible that there is some familiar good outweighing the fawn’s suffering and which is connected to that suffering in a way unbeknown to us. Or there may be goods we are not aware of, to which the fawn’s suffering is intimately connected. But although we do not know or cannot establish the truth of Q, we do possess rational grounds for accepting Q, and these grounds consist of the considerations adumbrated in P. Thus, the truth of P is taken to provide strong evidence for the truth of Q (Rowe 1979: 337).

3. The Skeptical Theist Response

Theism, particularly as expressed within the Judeo-Christian and Islamic religions, has always emphasized the inscrutability of the ways of God. In Romans 11:33-34, for example, the apostle Paul exclaims: “Oh, the depth of the riches of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable his judgments, and his paths beyond tracing out! Who has known the mind of the Lord?” (NIV). This emphasis on mystery and the epistemic distance between God and human persons is a characteristic tenet of traditional forms of theism. It is in the context of this tradition that Stephen Wykstra developed his well-known CORNEA critique of Rowe’s evidential argument. The heart of Wykstra’s critique is that, given our cognitive limitations, we are in no position to judge as improbable the statement that there are goods beyond our ken secured by God’s permission of many of the evils we find in the world. This position – sometimes labelled “skeptical theism” or “defensive skepticism” – has generated a great deal of discussion, leading some to conclude that “the inductive argument from evil is in no better shape than its late lamented deductive cousin” (Alston 1991: 61). In this Section, I will review the challenge posed by this theistic form of skepticism, beginning with the critique advanced by Wykstra.

a. Wykstra’s CORNEA Critique

In an influential paper entitled, “The Humean Obstacle to Evidential Arguments from Evil,” Stephen Wykstra raised a formidable objection to Rowe’s inference from P to Q. Wykstra’s first step was to draw attention to the following epistemic principle, which he dubbed “CORNEA” (short for “Condition Of ReasoNable Epistemic Access”):

(C) On the basis of cognized situation s, human H is entitled to claim “It appears that p” only if it is reasonable for H to believe that, given her cognitive faculties and the use she has made of them, if p were not the case, s would likely be different than it is in some way discernible by her. (Wykstra 1984: 85)

The point behind CORNEA may be easier to grasp if (C) is simplified along the following lines:

(C*) H is entitled to infer “There is no x“ from “So far as I can tell, there is no x” only if:

It is reasonable for H to believe that if there were an x, it is likely that she would perceive (or find, grasp, comprehend, conceive) it.

Adopting terminology introduced by Wykstra (1996), the inference from “So far as I can tell, there is no x” to “There is no x” may be called a “noseeum inference”: we no see ’um, so they ain’t there! Further, the italicized portion in (C*) may be called “the noseeum assumption,” as anyone who employs a noseeum inference and is justified in doing so would be committed to this assumption.

C*, or at least something quite like it, appears unobjectionable. If, for instance, I am looking through the window of my twentieth-floor office to the garden below and I fail to see any caterpillars on the flowers, that would hardly entitle me to infer that there are in fact no caterpillars there. Likewise, if a beginner were watching Kasparov play Deep Blue, it would be unreasonable for her to infer “I can’t see any way for Deep Blue to get out of check; so, there is none.” Both inferences are illegitimate for the same reason: the person making the inference does not have what it takes to discern the sorts of things in question. It is this point that C* intends to capture by insisting that a noseeum inference is permissible only if it is likely that one would detect or discern the item in question if it existed.

But how does the foregoing relate to Rowe’s evidential argument? Notice, to begin with, that Rowe’s inference from P to Q is a noseeum inference. Rowe claims in P that, so far as we can see, no goods justify God’s permission of E1 and E2, and from this he infers that no goods whatever justify God’s permission of these evils. According to Wykstra, however, Rowe is entitled to make this noseeum inference only if he is entitled to make the following noseeum assumption:

If there are goods justifying God’s permission of horrendous evil, it is likely that we would discern or be cognizant of such goods.

Call this Rowe’s Noseeum Assumption, or RNA for short. The key issue, then, is whether we should accept RNA. Many theists, led by Stephen Wykstra, have claimed that RNA is false (or that we ought to suspend judgement about its truth). They argue that the great gulf between our limited cognitive abilities and the infinite wisdom of God prevents us (at least in many cases) from discerning God’s reasons for permitting evil. On this view, even if there are goods secured by God’s permission of evil, it is likely that these goods would be beyond our ken. Alvin Plantinga (1974: 10) sums up this position well with his rhetorical question: “Why suppose that if God does have a reason for permitting evil, the theist would be the first to know?” (emphasis his). Since theists such as Wykstra and Plantinga challenge Rowe’s argument (and evidential arguments in general) by focusing on the limits of human knowledge, they have become known as skeptical theists.

I will now turn to some considerations that have been offered by skeptical theists against RNA.

b. Wykstra’s Parent Analogy

Skeptical theists have drawn various analogies in an attempt to highlight the implausibility of RNA. The most common analogy, and the one favoured by Wykstra, involves a comparison between the vision and wisdom of an omniscient being such as God and the cognitive capacities of members of the human species. Clearly, the gap between God’s intellect and ours is immense, and Wykstra (1984: 87-91) compares it to the gap between the cognitive abilities of a parent and her one-month-old infant. But if this is the case, then even if there were outweighing goods connected in the requisite way to the instances of suffering appealed to by Rowe, that we should discern most of these goods is just as likely as that a one-month-old infant should discern most of her parents’ purposes for those pains they allow her to suffer – that is to say, it is not likely at all. Assuming that CORNEA is correct, Rowe would not then be entitled to claim, for any given instance of apparently pointless suffering, that it is indeed pointless. For as the above comparison between God’s intellect and the human mind indicates, even if there were outweighing goods served by certain instances of suffering, such goods would be beyond our ken. What Rowe has failed to see, according to Wykstra, is that “if we think carefully about the sort of being theism proposes for our belief, it is entirely expectable – given what we know of our cognitive limits – that the goods by virtue of which this Being allows known suffering should very often be beyond our ken” (1984: 91).

c. Alston’s Analogies

Rowe, like many others, has responded to Wykstra’s Parent Analogy by identifying a number of relevant disanalogies between a one-month-old infant and our predicament as adult human beings (see Rowe 1996: 275). There are, however, various other analogies that skeptical theists have employed in order to cast doubt on RNA. Here I will briefly consider a series of analogies that were first formulated by Alston (1996).

Like Wykstra, Alston (1996: 317) aims to highlight “the absurdity of the claim” that the fact that we cannot see what justifying reason an omniscient, omnipotent being might have for doing something provides strong support for the supposition that no such reason is available to that being. Alston, however, chooses to steer clear of the parent-child analogy employed by Wykstra, for he concedes that this contains loopholes that can be exploited in the ways suggested by Rowe.

Alston’s analogies fall into two groups, the first of which attempt to show that the insights attainable by finite, fallible human beings are not an adequate indication of what is available by way of reasons to an omniscient, omnipotent being. Suppose I am a first-year university physics student and I am faced with a theory of quantum phenomena, but I struggle to see why the author of the theory draws the conclusions she draws. Does that entitle me to suppose that she has no sufficient reason for her conclusions? Clearly not, for my inability to discern her reasons is only to be expected given my lack of expertise in the subject. Similarly, given my lack of training in painting, I fail to see why Picasso arranged the figures in Guernica as he did. But that does not entitle me to infer that he had no sufficient reason for doing so. Again, being a beginner in chess, I fail to see any reason why Kasparov made the move he did, but I would be foolish to conclude that he had no good reason to do so.

Alston applies the foregoing to the noseeum inference from “We cannot see any sufficient reason for God to permit E1 and E2” to “God has no sufficient reason to do so.” In this case, as in the above examples, we are in no position to draw such a conclusion for we lack any reason to suppose that we have a sufficient grasp of the range of possible reasons open to the other party. Our grasp of the reasons God might have for his actions is thus comparable to the grasp of the neophyte in the other cases. Indeed, Alston holds that “the extent to which God can envisage reasons for permitting a given state of affairs exceeds our ability to do so by at least as much as Einstein’s ability to discern the reason for a physical theory exceeds the ability of one ignorant of physics” (1996: 318, emphasis his).

Alston’s second group of analogies seek to show that, in looking for the reasons God might have for certain acts or omissions, we are in effect trying to determine whether there is a so-and-so in a territory the extent and composition of which is largely unknown to us (or, at least, it is a territory such that we have no way of knowing the extent to which its constituents are unknown to us). Alston thus states that Rowe’s noseeum inference

…is like going from “We haven’t found any signs of life elsewhere in the universe” to “There isn’t life elsewhere in the universe.” It is like someone who is culturally and geographically isolated going from “As far as I have been able to tell, there is nothing on earth beyond this forest” to “There is nothing on earth beyond this forest.” Or, to get a bit more sophisticated, it is like someone who reasons “We are unable to discern anything beyond the temporal bounds of our universe,” where those bounds are the big bang and the final collapse, to “There is nothing beyond the temporal bounds of our universe.” (1996: 318)

Just as we lack a map of the relevant “territory” in these cases, we also lack a reliable internal map of the diversity of considerations that are available to an omniscient being in permitting instances of suffering. But given our ignorance of the extent, variety, or constitution of the terra incognita, it is surely the better part of wisdom to refrain from drawing any hasty conclusions regarding the nature of this territory.

Although such analogies may not be open to the same criticisms levelled against the analogies put forward by Wykstra, they are in the end no more successful than Wykstra’s analogies. Beginning with Alston’s first group of analogies, where a noseeum inference is unwarranted due to a lack of expertise, there is typically no expectation on the part of the neophyte that the reasons held by the other party (for example, the physicist’s reasons for drawing conclusion x, Kasparov’s reasons for making move x in a chess game) would be discernible to her. If you have just begun to study physics, you would not expect to understand Einstein’s reasons for advancing the special theory of relativity. However, if your five-year-old daughter suffered the fate of Sue as depicted in E2, would you not expect a perfectly loving being to reveal his reasons to you for allowing this to happen, or at least to comfort you by providing you with special assurances that that there is a reason why this terrible evil could not have been prevented? Rowe makes this point quite well:

Being finite beings we can’t expect to know all the goods God would know, any more than an amateur at chess should expect to know all the reasons for a particular move that Kasparov makes in a game. But, unlike Kasparov who in a chess match has a good reason not to tell us how a particular move fits into his plan to win the game, God, if he exists, isn’t playing chess with our lives. In fact, since understanding the goods for the sake of which he permits terrible evils to befall us would itself enable us to better bear our suffering, God has a strong reason to help us understand those goods and how they require his permission of the terrible evils that befall us. (2001b: 157)

There appears, then, to be an obligation on the part of a perfect being to not keep his intentions entirely hidden from us. Such an obligation, however, does not attach to a gifted chess player or physicist – Kasparov cannot be expected to reveal his game plan, while a physics professor cannot be expected to make her mathematical demonstration in support of quantum theory comprehensible to a high school physics student.

Similarly with Alston’s second set of analogies, where our inability to map the territory within which to look for x is taken to preclude us from inferring from our inability to find x that there is no x. This may be applicable to cases like the isolated tribesman’s search for life outside his forest or our search for extraterrestrial life, for in such scenarios there is no prior expectation that the objects of our search are of such a nature that, if they exist, they would make themselves manifest to us. However, in our search for God’s reasons we are toiling in a unique territory, one inhabited by a perfectly loving being who, as such, would be expected to make at least his presence, if not also his reasons for permitting evil, (more) transparent to us. This difference in prior expectations uncovers an important disanalogy between the cases Alston considers and cases involving our attempt to discern God’s intentions. Alston’s analogies, therefore, not only fail to advance the case against RNA but also suggest a line of thought in support of RNA. (For further discussion on RNA and divine hiddenness, see Trakakis (2003); see also Howard-Snyder & Moser (2002).)

4. Building a Theodicy, or Casting Light on the Ways of God

Most critics of Rowe’s evidential argument have thought that the problem with the argument lies with its factual premise. But what, exactly, is wrong with this premise? According to one popular line of thought, the factual premise can be shown to be false by identifying goods that we know of that would justify God in permitting evil. To do this is to develop a theodicy.

a. What Is a Theodicy?

The primary aim of the project of theodicy may be characterized in John Milton’s celebrated words as the attempt to “justify the ways of God to men.” That is to say, a theodicy aims to vindicate the justice or goodness of God in the face of the evil found in the world, and this it attempts to do by offering a reasonable explanation as to why God allows evil to abound in his creation.

A theodicy may be thought of as a story told by the theist explaining why God permits evil. Such a story, however, must be plausible or reasonable in the sense that it conforms to all of the following:

- commonsensical views about the world (for example, that there exist other people, that there exists a mind-independent world, that much evil exists);

- widely accepted scientific and historical views (for example, evolutionary theory), and

- intuitively plausible moral principles (for example, generally, punishment should not be significantly disproportional to the offence committed).

Judged by these criteria, the story of the Fall (understood in a literalist fashion) could not be offered as a theodicy. For given the doubtful historicity of Adam and Eve, and given the problem of harmonizing the Fall with evolutionary theory, such an account of the origin of evil cannot reasonably held to be plausible. A similar point could be made about stories that attempt to explain evil as the work of Satan and his cohorts.

b. Distinguishing a “Theodicy” from a “Defence”

An important distinction is often made between a defence and a theodicy. A theodicy is intended to be a plausible or reasonable explanation as to why God permits evil. A defence, by contrast, is only intended as a possible explanation as to why God permits evil. A theodicy, moreover, is offered as a solution to the evidential problem of evil, whereas a defence is offered as a solution to the logical problem of evil. Here is an example of a defence, which may clarify this distinction:

It will be recalled that, according to Mackie, it is logically impossible for the following two propositions to be jointly true:

- God is omnipotent, omniscient, and perfectly good,

- Evil exists.

Now, consider the following proposition:

- Every person goes wrong in every possible world.

In other words, every free person created by God would misuse their free will on at least one occasion, no matter which world (or what circumstances) they were placed in. This may be highly implausible, or even downright false – but it is, at least, logically possible. And if (3) is possible, then so is the following proposition:

- It was not within God’s power to create a world containing moral good but no moral evil.

In other words, it is possible that any world created by God that contains some moral good will also contain some moral evil. Therefore, it is possible for both (1) and (2) to be jointly true, at least when (2) is said to refer to “moral evil.” But what about “natural evil”? Well, consider the following proposition:

- All so-called “natural evil” is brought about by the devious activities of Satan and his cohorts.

In other words, what we call “natural evil” is actually “moral evil” since it results from the misuse of someone’s free will (in this case, the free will of some evil demon). Again, this may be highly implausible, or even downright false – but it is, at least, possibly true.

In sum, Mackie was wrong to think that it is logically impossible for both (1) and (2) to be true. For if you conjoin (4) and (5) to (1) and (2), it becomes clear that it is possible that any world created by God would have some evil in it. (This, of course, is the famous free will defence put forward in Plantinga 1974: ch.9). Notice that the central claims of this defence – namely, (3), (4), and (5) – are only held to be possibly true. That’s what makes this a defence. One could not get away with this in a theodicy, for a theodicy must be more than merely possibly true.

c. Sketch of a Theodicy

What kind of theodicy, then, can be developed in response to Rowe’s evidential argument? Are there any goods we know of that would justify God in permitting evils like E1 and E2? Here I will outline a proposal consisting of three themes that have figured prominently in the recent literature on the project of theodicy.

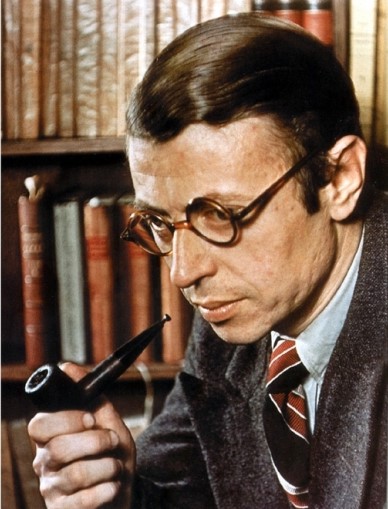

(1) Soul-making. Inspired by the thought of the early Church Father, Irenaeus of Lyon (c.130-c.202 CE), John Hick has put forward in a number of writings, but above all in his 1966 classic Evil and the God of Love, a theodicy that appeals to the good of soul-making (see also Hick 1968, 1977, 1981, 1990). According to Hick, the divine intention in relation to humankind is to bring forth perfect finite personal beings by means of a “vale of soul-making” in which humans may transcend their natural self-centredness by freely developing the most desirable qualities of moral character and entering into a personal relationship with their Maker. Any world, however, that makes possible such personal growth cannot be a hedonistic paradise whose inhabitants experience a maximum of pleasure and a minimum of pain. Rather, an environment that is able to produce the finest characteristics of human personality – particularly the capacity to love – must be one in which “there are obstacles to be overcome, tasks to be performed, goals to be achieved, setbacks to be endured, problems to be solved, dangers to be met” (Hick 1966: 362). A soul-making environment must, in other words, share a good deal in common with our world, for only a world containing great dangers and risks, as well as the genuine possibility of failure and tragedy, can provide opportunities for the development of virtue and character. A necessary condition, however, for this developmental process to take place is that humanity be situated at an “epistemic distance” from God. On Hick’s view, in other words, if we were initially created in the direct presence of God we could not freely come to love and worship God. So as to preserve our freedom in relation to God, the world must be created religiously ambiguous or must appear, to some extent at least, as if there were no God. And evil, of course, plays an important role in creating the desired epistemic distance.

(2) Free will. The appeal to human freedom, in one guise or another, constitutes an enduring theme in the history of theodicy. Typically, the kind of freedom that is invoked by the theodicist is the libertarian sort, according to which I am free with respect to a particular action at time t only if the action is not determined by all that happened or obtained before t and all the causal laws there are in such a way that the conjunction of the two (the past and the laws) logically entails that I perform the action in question. My mowing the lawn, for instance, constitutes a voluntary action only if, the state of the universe (including my beliefs and desires) and laws of nature being just as they were immediately preceding my decision to mow the lawn, I could have chosen or acted otherwise than I in fact did. In this sense, the acts I perform freely are genuinely “up to me” – they are not determined by anything external to my will, whether these be causal laws or even God. And so it is not open to God to cause or determine just what actions I will perform, for if he does so those actions could not be free. Freedom and determinism are incompatible.

The theodicist, however, is not so much interested in libertarian freedom as in libertarian freedom of the morally relevant kind, where this consists of the freedom to choose between good and evil courses of action. The theodicist’s freedom, moreover, is intended to be morally significant, not only providing one with the capacity to bring about good and evil, but also making possible a range of actions that vary enormously in moral worth, from great and noble deeds to horrific evils.

Armed therefore with such a conception of freedom, the free will theodicist proceeds to explain the existence of moral evil as a consequence of the misuse of our freedom. This, however, means that responsibility for the existence of moral evil lies with us, not with God. Of course, God is responsible for creating the conditions under which moral evil could come into existence. But it was not inevitable that human beings, if placed in those conditions, would go wrong. It was not necessary, in other words, that humans would misuse their free will, although this always was a possibility and hence a risk inherent in God’s creation of free creatures. The free will theodicist adds, however, that the value of free will (and the goods it makes possible) is so great as to outweigh the risk that it may be misused in various ways.

(3) Heavenly bliss. Theodicists sometimes draw on the notion of a heavenly afterlife to show that evil, particularly horrendous evil, only finds its ultimate justification or redemption in the life to come. Accounts of heaven, even within the Christian tradition, vary widely. But one common feature in these accounts that is relevant to the theodicist’s task is the experience of complete felicity for eternity brought about by intimate and loving communion with God. This good, as we saw, plays an important role in Hick’s theodicy, and it also finds a central place in Marilyn Adams’ account of horrendous evil.

Adams (1986: 262-63, 1999: 162-63) notes that, on the Christian world-view, the direct experience of “face-to-face” intimacy with God is not only the highest good we can aspire to enjoy, but is also an incommensurable good – more precisely, it is incommensurable with respect to any merely temporal evils or goods. As the apostle Paul put it, “our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us” (Rom 8:18, NIV; compare 2 Cor 4:17). This glorification to be experienced in heaven, according to Adams, vindicates God’s justice and love toward his creatures. For the experience of the beatific vision outweighs any evil, even evil of the horrendous variety, that someone may suffer, thus ensuring a balance of good over evil in the sufferer’s life that is overwhelmingly favourable. But as Adams points out, “strictly speaking, there will be no balance to be struck” (1986: 263, emphasis hers), since the good of the vision of God is incommensurable with respect to one’s participation in any temporal or created evils. And so an everlasting, post-mortem beatific vision of God would provide anyone who experienced it with good reason for considering their life – in spite of any horrors it may have contained – as a great good, thus removing any grounds of complaint against God.

Bringing these three themes together, a theodicy can be developed with the aim of explaining and justifying God’s permission of evil, even evil of the horrendous variety. To illustrate how this may be done, I will concentrate on Rowe’s E2 and the Holocaust, two clear instances of horrendous moral evil.

Notice that these two evils clearly involve a serious misuse of free will on behalf of the perpetrators. We could, therefore, begin by postulating God’s endowment of humans with morally significant free will as the first good that is served by these evils. That is to say, God could not prevent the terrible suffering and death endured by Sue and the millions of Holocaust victims while at the same time creating us without morally significant freedom – the freedom to do both great evil and great good. In addition, these evils may provide an opportunity for soul-making – in many cases, however, the potential for soul-making would not extend to the victim but only to those who cause or witness the suffering. The phenomenon of “jailhouse conversions,” for example, testifies to the fact that even horrendous evil may occasion the moral transformation of the perpetrator. Finally, to adequately compensate the victims of these evils we may introduce the doctrine of heaven. Postmortem, the victims are ushered into a relation of beatific intimacy with God, an incommensurable good that “redeems” their past participation in horrors. For the beatific vision in the afterlife not only restores value and meaning to the victim’s life, but also provides them with the opportunity to endorse their life (taken as a whole) as worthwhile.

Does this theodicy succeed in exonerating God? Various objections could, of course, be raised against such a theodicy. One could, for example, question the intelligibility or empirical adequacy of the underlying libertarian notion of free will (see, for example, Pereboom 2001: 38-88). Or one might follow Tooley (1980:373-75) and Rowe (1996: 279-81, 2001a: 135-36) in thinking that, just as we have a duty to curtail another person’s exercise of free will when we know that they will use their free will to inflict considerable suffering on an innocent (or undeserving) person, so too does God have a duty of this sort. On this view, a perfectly good God would have intervened to prevent us from misusing our freedom to the extent that moral evil, particularly moral evil of the horrific kind, would either not occur at all or occur on a much more infrequent basis. Finally, how can the above theodicy be extended to account for natural evil? Various proposals have been offered here, the most prominent of which are: Hick’s view that natural evil plays an essential part in the “soul-making” process; Swinburne’s “free will theodicy for natural evil” – the idea, roughly put, is that free will cannot be had without the knowledge of how to bring about evil (or prevent its occurrence), and since this knowledge of how to cause evil can only be had through prior experience with natural evil, it follows that the existence of natural evil is a logically necessary condition for the exercise of free will (see Swinburne 1978, 1987: 149-67, 1991: 202-214, 1998: 176-92); and “natural law theodicies,” such as that developed by Reichenbach (1976, 1982: 101-118), according to which the natural evils that befall humans and animals are the unavoidable by-products of the outworking of the natural laws governing God’s creation.

5. Further Responses to the Evidential Problem of Evil

Let’s suppose that Rowe’s evidential argument from evil succeeds in providing strong evidence in support of the claim that there does not exist an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good being. What follows from this? In particular, would a theist who finds its impossible to fault Rowe’s argument be obliged to give up her theism? Not necessarily, for at least two further options would be available to such a theist.

Firstly, the theist may agree that Rowe’s argument provides some evidence against theism, but she may go on to argue that there is independent evidence in support of theism which outweighs the evidence against theism. In fact, if the theist thinks that the evidence in support of theism is quite strong, she may employ what Rowe (1979: 339) calls “the G.E. Moore shift” (compare Moore 1953: ch.6). This involves turning the opponent’s argument on its head, so that one begins by denying the very conclusion of the opponent’s argument. The theist’s counter-argument would then proceed as follows:

(not-3) There exists an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good being. (2) An omniscient, wholly good being would prevent the occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. (not-1) (Therefore) It is not the case that there exist instances of horrendous evil which an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

Although this strategy has been welcomed by many theists as an appropriate way of responding to evidential arguments from evil (for example, Mavrodes 1970: 95-97, Evans 1982: 138-39, Davis 1987: 86-87, Basinger 1996: 100-103) – indeed, it is considered by Rowe to be “the theist’s best response” (1979: 339) – it is deeply problematic in a way that is often overlooked. The G.E. Moore shift, when employed by the theist, will be effective only if the grounds for accepting not-(3) [the existence of the theistic God] are more compelling than the grounds for accepting not-(1) [the existence of gratuitous evil]. The problem here is that the kind of evidence that is typically invoked by theists in order to substantiate the existence of God – for example, the cosmological and design arguments, appeals to religious experience – does not even aim to establish the existence of a perfectly good being, or else, if it does have such an aim, it faces formidable difficulties in fulfilling it. But if this is so, then the theist may well be unable to offer any evidence at all in support of not-(3), or at least any evidence of a sufficiently strong or cogent nature in support of not-(3). The G.E. Moore shift, therefore, is not as straightforward a strategy as it initially seems.

Secondly, the theist who accepts Rowe’s argument may claim that Rowe has only shown that one particular version of theism – rather than every version of theism – needs to be rejected. A process theist, for example, may agree with Rowe that there is no omnipotent being, but would add that God, properly understood, is not omnipotent, or that God’s power is not as unlimited as is usually thought (see, for example, Griffin 1976, 1991). An even more radical approach would be to posit a “dark side” in God and thus deny that God is perfectly good. Theists who adopt this approach (for example, Blumenthal 1993, Roth 2001) would also have no qualms with the conclusion of Rowe’s argument.