Kant: Philosophy of Mind

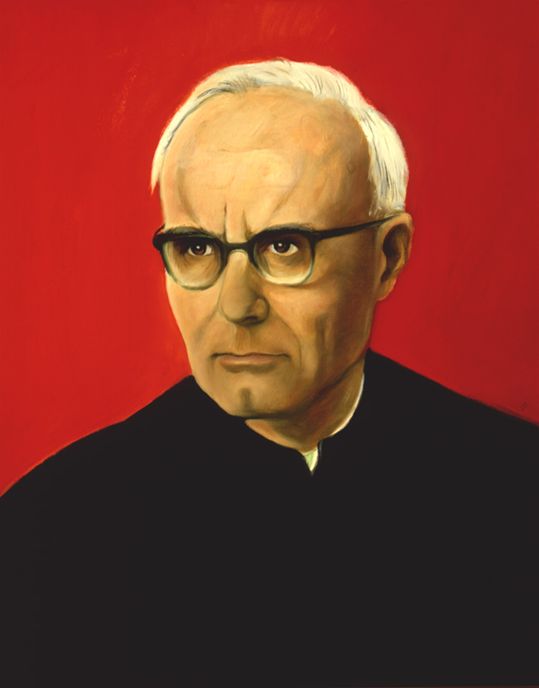

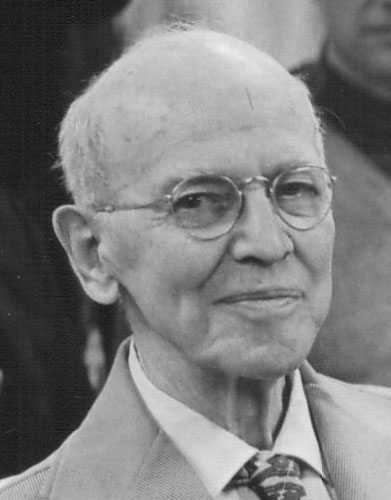

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was one of the most important philosophers of the Enlightenment Period (c. 1650-1800) in Western European history. This encyclopedia article focuses on Kant’s views in the philosophy of mind, which undergird much of his epistemology and metaphysics. In particular, it focuses on metaphysical and epistemological doctrines forming the core of Kant’s mature philosophy, as presented in the Critique of Pure Reason (CPR) of 1781/87 and elsewhere.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was one of the most important philosophers of the Enlightenment Period (c. 1650-1800) in Western European history. This encyclopedia article focuses on Kant’s views in the philosophy of mind, which undergird much of his epistemology and metaphysics. In particular, it focuses on metaphysical and epistemological doctrines forming the core of Kant’s mature philosophy, as presented in the Critique of Pure Reason (CPR) of 1781/87 and elsewhere.

There are certain aspects of Kant’s project in the CPR that should be very familiar to anyone versed in the debates of seventeenth century European philosophy. For example, Kant argues, like Locke and Hume before him, that the boundaries of substantive human knowledge stop at experience, and thus that we must be extraordinarily circumspect concerning any claim made about what reality is like independent of all possible human experience. But, like Descartes and Leibniz, Kant thinks that central parts of human knowledge nevertheless exhibit characteristics of necessity and universality, and that, contrary to Hume’s skeptical arguments, there is good reason to think so.

Kant carries out a ‘critique’ of pure reason in order to show its nature and limits, thereby curbing the pretensions of various metaphysical systems articulated on the basis that reason alone allows us to scrutinize the depths of reality. But Kant also argues that the legitimate domain of reason is more extensive and more substantive than previous empiricist critiques had allowed. In this way Kant salvages (or attempts to) much of the prevailing Enlightenment conception of reason as an organ for knowledge of the world.

This article discusses Kant’s theory of cognition, including his views of the various mental faculties that make cognition possible. It distinguishes between different conceptions of consciousness at the basis of this theory of cognition and explains and discusses Kant’s criticisms of the prevailing rationalist conception of mind, popular in Germany at the time.

Table of Contents

- Kant’s Theory of Cognition

- Consciousness

- Concepts and Perception

- Rational Psychology and Self-Knowledge

- Summary

- References and Further Reading

1. Kant’s Theory of Cognition

Kant is primarily interested in investigating the mind for epistemological reasons. One of the goals of his mature “critical” philosophy is articulating the conditions under which our scientific knowledge, including mathematics and natural science, is possible. Achieving this goal requires, in Kant’s estimation, a critique of the manner in which rational beings like ourselves gain such knowledge, so that we might distinguish those forms of inquiry that are legitimate, such as natural science, from those that are illegitimate, such as rationalist metaphysics. This critique proceeds via an examination of those features of the mind relevant to the acquisition of knowledge. This examination amounts to a survey of the conditions for “cognition” [Erkenntnis], or the mind’s relation to an object. Although there is some controversy about the best way to understand Kant’s use of this term, this article will understand it as involving relation to a possible object of experience, and as being a necessary condition for positive substantive knowledge (Wissen). Thus to understand Kant’s critical philosophy, we need to understand his conception of the mind.

a. Mental Faculties and Mental Representation

Kant characterizes the mind along two fundamental axes – first by the various kinds of powers which it possesses and second by the results of exercising those powers.

At the most basic explanatory level, Kant conceives of the mind as constituted by two fundamental capacities [Fähigkeiten], or powers, which he labels “receptivity” [Receptivität] and “spontaneity” [Spontaneität]. Receptivity, as the name suggests, constitutes the mind’s capacity to be affected by something, whether itself or something else. In other words, the mind’s receptive power essentially requires some external prompt to engage in producing “representations” [Vorstellungen], which are best thought of as discrete mental events or states, of which the mind is aware, or in virtue of which the mind is aware of something else (it is controversial whether representations are objects of ultimate awareness or are merely a vehicle for such awareness). In contrast, the power of spontaneity needs no such prompt. It is able to initiate its activity from itself, without any external trigger.

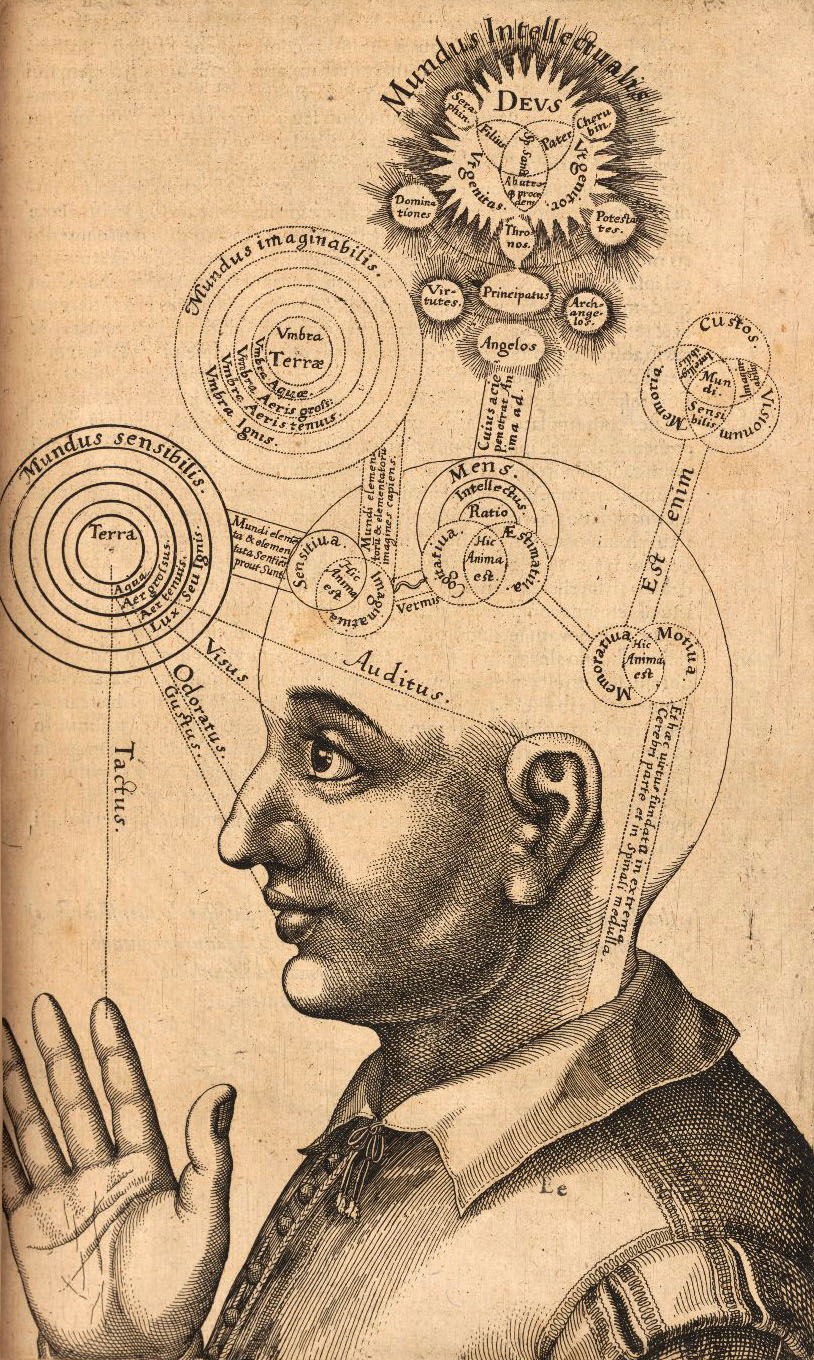

These two capacities of the mind are the basis for all (human) mental behavior. Kant thus construes all mental activity either in terms of its resulting from affection (receptivity) or from the mind’s self-prompted activity (spontaneity). From these two very general aspects of the mind Kant then derives three further basic faculties or “powers” [Vermögen], termed by Kant “sensibility” [Sinnlichkeit], “understanding” [Verstand], and “reason” [Vernunft]. These faculties characterize specific cognitive powers. These powers cannot be reduced to any of the others, and each is assigned a particular, cognitive task.

i. Sensibility, Understanding, and Reason

Kant distinguishes the three fundamental mental faculties from one another in two ways. First, he construes sensibility as the specific manner in which human beings, as well as other animals, are receptive. This is in contrast with the faculties of understanding and reason, which are forms of human, or all rational beings, spontaneity. Second, Kant distinguishes the faculties by their output. All of the mental faculties produce representations. We can see these distinctions at work in what is generally called the “stepladder” [Stufenleiter] passage from the Transcendental Dialectic of Kant’s major work, the Critique of Pure Reason (1781/7). This is one of the few places in the entire Kantian corpus where Kant explicitly discusses the meanings of and relations between his technical terms, and defines and classifies varieties of representation.

The genus is representation (representatio) in general. Under it stand representations with consciousness (perceptio). A perception [Wahrnehmung], that relates solely to a subject as a modification of its state, is sensation (sensatio). An objective perception is cognition (cognitio). This is either intuition or concept (intuitus vel conceptus). The first relates immediately to the object and is singular; the second is mediate, conveyed by a mark, which can be common to many things. A concept is either an empirical or a pure concept, and the pure concept, insofar as it has its origin solely in the understanding (not in a pure image of sensibility), is called notio. A concept made up of notions, which goes beyond the possibility of experience, is an idea or a concept of reason. (A320/B376–7).

As Kant’s discussion here indicates, the category of representation contains sensations [Empfindungen], intuitions [Anschauungen], and concepts [Begriffe]. Sensibility is the faculty that provides sensory representations. Sensibility generates representations based on being affected either by entities distinct from the subject or by the subject herself. This is in contrast to the faculty of understanding, which generates conceptual representations spontaneously – i.e. without advertence to affection. Reason is that spontaneous faculty by which special sorts of concepts, which Kant calls ‘ideas’ or ‘notions’, may be generated, and whose objects could never be met with in “experience,” which Kant defines as perceptions connected by fundamental concepts. Some of reason’s ideas include those concerning God and the soul.

Kant claims that all the representations generated via sensibility are structured by two “forms” of intuition—space and time—and that all sensory aspects of our experience are their “matter” (A20/B34). The simplest way of understanding what Kant means by “form” here is that anything one might experience will have either have spatial features, such as extension, shape, and location, or temporal features, such as being successive or simultaneous. So the formal element of an empirical intuition, or sense perception, will always be either spatial or temporal. Meanwhile, the material element is always sensory (in the sense of determining the phenomenal or “what it is like” character of experience) and tied either to one or more of the five senses or the feelings of pleasure and displeasure.

Kant ties the two forms of intuition to two distinct spheres or domains, the “inner” and the “outer.” The domain of outer intuition concerns the spatial world of material objects while the domain of inner intuition concerns temporally ordered states of mind. Space is thus the form of “outer sense” while time is the form of “inner sense” (A22/B37; cf. An 7:154). In the Transcendental Aesthetic, Kant is primarily concerned with “pure” [rein] intuition, or intuition absent any sensation, and often only speaks in passing of the sense perception of physical bodies (for example A20–1/B35). However, Kant more clearly links the five senses with intuition in his 1798 work Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, in the section entitled “On the Five Senses.”

Sensibility in the cognitive faculty (the faculty of intuitive representations) contains two parts: sense and the imagination…But the senses, on the other hand, are divided into outer and inner sense (sensus internus); the first is where the human body is affected by physical things, the second is where the human body is affected by the mind (An 7:153).

Kant characterizes intuition generally in terms of two characteristics—namely immediacy [Unmittelbarkeit] and particularity [Einzelheit] (cf. A19/B33, A68/B93; JL 9:91). This is in contrast to the mediacy and generality [Allgemeinheit] characteristic of conceptual representation (A68/B93; JL 9:91).

Kant contrasts the particularity of intuition with the generality of concepts in the “stepladder” passage. Specifically, Kant says a concept is related to its object via “a mark, which can be common to many things” (A320/B377). This suggests that intuition, in contrast to concepts, puts a subject in cognitive contact with features of an object that are unique to particular objects and are not had by other objects. Some debate whether the immediacy of intuition is compatible with an intuition’s relating to an object by means of marks, or whether relation by means of marks entails mediacy and, thus, that only concepts relate to objects by means of marks. See Smit (2000) for discussion. Spatio-temporal properties seem like excellent candidates for such features, as no two objects of experience can have the very same spatio-temporal location (B327-8). But perhaps any non-repeatable, non-universal feature of a perceived object will do. For relevant discussion see Smith (2000); Grüne (2009), 50, 66-70.

Though Kant’s discussion of intuition suggests that it is a form of perceptual experience, this might seem to clash with his distinction between “experience” [Erfahrung] and “intuition” [Anschauung]. In part, this is a terminological issue. Kant’s notion of an “experience” is typically quite a bit narrower than our contemporary English usage of the term. Kant actually equates, at several points, “experience” with “empirical cognition” (B166, A176/B218, A189/B234), which is incompatible with experience being falsidical in any way. He also gives indications that experience, in his sense, is not something had by a single subject. See, for example, his claim that there is only one experience (A230/B282-3).

Kant also distinguishes intuition from “perception” [Wahrnehmung], which he characterizes as the conscious apprehension of the content of an intuition (Pr 4:300; cf. A99, A119-20, B162, and B202-3). “Experience,” in Kant’s sense, is then construed as a set of perceptions that are connected via fundamental concepts that Kant entitles the “categories.” As he puts it, “Experience is cognition through connected perceptions [durch verknüpfte Wahrnehmungen]” (B161; cf. B218; Pr 4:300).

Empirical intuition, perception, and experience, in Kant’s usage of these terms, all denote kinds of “experience” as we use the term in contemporary English. At its most primitive level, empirical intuition presents some feature of the world to the mind in a sensory manner. Empirical intuition does so in such a way that the intuition’s subject is in a position to distinguish that feature from others. A perception, in Kant’s sense, requires awareness of the basis by which the feature is different from other things. Kant uses the term in a variety of ways, however—JL 9:64-5, for instance—so there is some controversy surrounding the proper understanding of this term. One has a perception, in Kant’s sense, when one can not only discriminate one thing from another, or between the parts of a single thing, based on a sensory apprehension of it, but also can articulate exactly which features of the object or objects that distinguish it from others. For instance, one can say it is green rather than red, or that it occupies this spatial location rather than that one. Intuition thus allows for the discrimination of distinct objects via an awareness of their features, while perception allows for an awareness of what specifically distinguishes an object from others. “Experience,” in Kant’s sense, is even further up the cognitive ladder (see JL 9:64-5), insofar as it indicates an awareness of features, such as the substantiality of a thing, its causal relations with other beings, and its mereological features, that is part-whole dependence relations.

Kant thus believes that the capacity to cognitively ascend from mere discriminatory awareness of one’s environment (intuition), to an awareness of those features by means of which one discriminates (perception), and finally to an awareness of the objects which ground these features (experience), depends on the kinds of mental processes of which the subject is capable.

Before turning to the issue of mental processing, which figures centrally in Kant’s overall critical project, there are two further faculties of the mind that are worth discussion— the faculties of judgment imagination. These faculties are not obviously as fundamental as the faculties of sensibility, understanding, and reason, but they nevertheless play a central role in Kant’s thinking about the structure of the mind and its contributions to our experience of the world.

ii. Imagination and Judgment

Kant links the faculty of imagination closely to sensibility. For example, in his Anthropology he says,

Sensibility in the cognitive faculty (the faculty of intuitive representations) contains two parts: sense and the power of imagination. The first is the faculty of intuition in the presence of an object, the second is intuition even without the presence of an object. (An 7:153; cf. 7:167; B151; LM 29:881; LM 28:449, 673)

The contrast Kant makes here is not entirely obvious, but includes at least the difference between cases of occurrent sensory experience of a perceived object—seeing the brown table before you—and cases of sensory recollection of a previously perceived object—visually imagining the brown table that was once in front of you. Kant makes this clearer in the process of further distinguishing between different kinds of imagination.

The power of imagination (facultas imaginandi), as a faculty of intuition without the presence of the object, is either productive, that is, a faculty of the original presentation [Darstellung] of the object (exhibitio originaria), which thus precedes experience; or reproductive, a faculty of the derivative presentation of the object (exhibitio derivativa), which brings back to mind an empirical intuition that it had previously (An 7:167).

So, in the operation of productive imagination, one brings to mind a sensory experience that is not itself based on any object previously so experienced. This is not to say the productive imagination is totally creative. Kant explicitly denies (An 7:167) that the productive imagination has the power to generate wholly novel sensory experience. It could not, in a person born blind, produce the phenomenal quality associated with the experience of seeing a red object, for example. If the productive imagination is instrumental in producing sensory fictions, the reproductive imagination is instrumental in producing sensory experiences of previously perceived objects.

Imagination thus plays a central role in empirical cognition by serving as the basis for both memory and the creative arts. In addition it also plays a kind of mediating role between the faculties of sensibility and understanding. Kant calls this mediating role a “transcendental function” of the imagination (A124). It mediates and transcends by being tied in its functioning to both faculties. On one hand, it produces sensible representations, and is thus connected to sensibility. On the other hand, it is not a purely passive faculty but rather engages in the activity of bringing together various representations, as does memory, for example, .Kant explicitly connects understanding with this kind of active mental processing.

Kant also goes so far as to claim that the activity of imagination is a necessary part of what makes perception, in his technical sense of a string of connected, conscious sensory experiences, possible (A120, note). Though Kant’s view concerning the exact role of imagination in sensory experience is contested, two points emerge as central. First, Kant belives imagination plays a crucial role in the generation of complex sensory representations of an object (see Sellars (1978) for an influential example of this interpretation). It is imagination that makes it possible to have a sensory experience of a complex, three-dimensional, and geometric figure whose identity remains constant even as it is subject to translations and rotations in space. Second, Kant regards imagination’s mediating role between sensibility and understanding as crucial for at least some kinds of concept application (see Guyer (1987) and Pendlebury (1995) for further discussion). This mediating role involves what Kant calls the “schematization” of a concept and an additional mental faculty, that of judgment.

Kant defines the faculty of judgment as “the capacity to subsume under rules, that is, to distinguish whether something falls under a given rule” (A132/B171). However, he spends comparatively little time discussing this faculty in the first Critique. There, it seems to be discussed as an extension of the understanding in that it applies concepts to empirical objects. It is not until the third Critique—Kant’s 1790 Critique of Judgment—that Kant distinguishes judgment as an independent faculty with a special role. There Kant specifies two different ways it might function (CJ 5:179; cf. CJ (First Introduction) 20:211)

In one, judgment subsumes given objects under concepts, which are themselves already given. This role appears identical to the role he assigns judgment in the Critique of Pure Reason. The basic idea is that judgment functions to assign an intuited object—a dog—to the correct concept—such as domestic animals. This concept is presumed to be one already possessed by the subject. In this activity, the faculty overlaps with the role Kant singles out for imagination in the section of the first Critique entitled ‘On the Schematism of the Pure Concepts of the Understanding.’ Both are conceived of here in terms of the ultimate functioning of understanding, since it is understanding that generates concepts.

The second role for the faculty of judgment, and what seems to make it a distinctive faculty in its own right, is that of finding a concept under which to “subsume” experienced objects. This is called judgment’s “reflecting” role (CJ 5:179). Here, the subject exercises judgment in generating an appropriate concept for what is given by intuition (CJ (First Introduction) 20:211-13; JL 9:94–95; for discussion see Longuenesse (1998), 163–166 and 195–197; Ginsborg (2006).

In addition to the generation of empirical concepts, Kant also describes reflective judgment as responsible for scientific inquiry. It must sort and classify objects in nature into a hierarchical taxonomy of genus/species relationships. Kant also utilizes the notion of reflective judgment to unify the otherwise seemingly unrelated topics of the Critique of Judgment—aesthetic judgments and teleological judgments concerning the order of nature.

Thus far, the discussion of Kant’s view of the mind has focused primarily on the various mental faculties and their corresponding representational output. Both the faculty of imagination and that of judgment operate on representations given from sensibility and understanding. In general, Kant conceives of the mind’s activity in terms of different methods of “processing” representations.

b. Mental Processing

Kant’s term for mental processing is “combination” [Verbindung], and the form of combination with which he is primarily concerned is what he calls “synthesis.” Kant characterizes synthesis as that activity by which understanding “runs through” and “gathers together” representations given to it by sensibility in order to form concepts, judgments, and ultimately, for any cognition to take place at all (A77-8/B102-3). Synthesis is not something people are typically aware of doing. As Kant says, it is a “a blind though indispensable function of the soul…of which we are only seldom even conscious (A78/B103)”.

Synthesis is carried out by the unitary subject of representation upon representations either given to the subject by sensibility or produced by the subject through thought. Intellectual synthesis occurs when synthesis is used on representations and forms the content of a concept or judgment. When carried out by the imagination on material provided by sensibility, it is called “figurative” synthesis (B150-1). In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant is primarily concerned with synthesis performed on representations provided by sensibility, and he discusses three central kinds of synthesis—apprehension, reproduction (or imagination), and recognition (or conceptualization) (A98-110/B159-61). Though Kant discusses these forms of synthesis as if they were discrete types of mental acts, it seems that the first two forms must occur together, while the third only may occur as well (compare Brook (1997); Allais (2009).

One of the central topics of debate in the interpretation of Kant’s views on synthesis is whether Kant endorses conceptualism. Roughly, conceptualism claims the capacity for conscious sensory experience of the objective world depends, at least in part, on the repertoire of concepts possessed by the experiencing subject, insofar as those concepts are exercised in acts of synthesis by understanding.

Kant typically contrasts synthesis with other ways in which representations might be related, most importantly, by association (for example B139-40). Association is primarily a passive process by which the mind comes to connect representations due to repeated exposure of the subject to certain kinds of regularities. One might, for example, associate thoughts of chicken soup with thoughts of being ill, if one only had chicken soup when one was ill. In contrast, synthesis is a fundamentally active process that depends upon the mind’s spontaneity and is the means by which genuine judgment is possible.

Consider, for example, the difference between the merely associative transition between holding a stone and feeling its weight compared to the judgment that the stone is heavy (B142). The association of holding the stone and feeling its weight is not yet a judgment about the stone, but a kind of involuntary connection between two states of oneself. In contrast, thinking the stone is heavy moves beyond associating two feelings to a thought about how things are objectively, independent of one’s own mental states (Pereboom (1995), Pereboom (2006)). One of Kant’s most important points concerning mental processing is that association cannot explain the possibility of objective judgment. What is required, he says, is a theory of mental processing by an active subject capable of acts of synthesis.

Several of the important differences between synthesis and association can be summarized as follows (Pereboom (1995), 4-7):

- The source of synthesis is to be found in a subject, and the subject is distinct from its states.

- Synthesis can employ a priori concepts, concepts independent of experience, as modes of processing representations, whereas association never does.

- Synthesis is the product of a causally active subject. It is produced by a cause that is realized in the subject’s faculty, either the imagination or the understanding.

Kant’s conception of synthesis and judgment is tied to his conception of “consciousness” [Bewußtsein] and “self-consciousness” [Selbstbewußtsein]. However, both notions require some significant unpacking.

2. Consciousness

The notion of consciousness [Bewußtsein] plays an important role in Kant’s philosophy. There are, however, several different senses of “consciousness” in play in Kant’s work, not all of which line up with contemporary philosophical usage. Below, several of Kant’s most central notions and their differences from and relations to contemporary usage are explained.

a. Phenomenal Consciousness

Philosophical discussions of consciousness typically focus on phenomenal consciousness, or “what it is like” to have a conscious experience of a particular kind, such as seeing the color red or smelling a rose. Such qualitative features of consciousness have been of major concern to philosophers of the late 20th Century. However, the metaphysical issue of phenomenal consciousness is almost entirely ignored by Kant, perhaps because he is unconcerned with problems stemming from commitments to naturalism or physicalism. He seems to attribute all qualitative characteristics of consciousness to sensation and what he calls “feeling” [Gefühl] (CJ 5:206). Kant distinguishes between sensation and feeling in terms of an objective/subjective distinction. Sensations indicate or present features of objects, distinct from the subject. Feelings, by contrast, present only states of the subject to consciousness. Kant’s typical examples of such feelings include pain and pleasure (B66-7; CJ 5:189, 203-6).

Kant clearly assigns a cognitive role to sensation and allows that it is “through sensation” that we cognitively relate to objects given in sensibility (A20/B34). Despite that, he does not focus in any substantive or systematic way on the phenomenal aspects of sensory consciousness, nor does he focus on how exactly they aid in cognition of the empirical world.

b. Discrimination and Differentiation

The central notion of “consciousness” with which Kant is concerned is that of discrimination or differentiation. This is the same conception of consciousness mostly used in Kant’s time, particularly by his major predecessors Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) and Christian Wolff (1679-1754), and Kant gives little indication that he departs from their general practice.

According to Kant, any time a subject can discriminate one thing from another, the subject is, or can be, conscious of that one thing. (An 7:136-8). Representations which allow for discrimination and differentiation are “clear” [klar]. Representations which allow not only for the differentiation of one thing from others (such as differentiating one person’s face from another’s), but also the differentiation of parts of the thing so discriminated (such as differentiating the different parts of a person’s face) are called “distinct” [deutlich].

Kant does seem to deny the Leibniz-Wolff tradition that clarity can simply be equated with consciousness (B414-15, note). Primarily, he seems motivated to allow that one’s discriminatory capacities may outrun one’s capacity for memory or even the explicit articulation of that which is discriminated. In such cases, one does not have a fully clear representation.

Kant’s conception of “obscure” [dunkel] representation is that it allows the subject to discriminate differentially between aspects of her environment without any explicit awareness of how she does so. This connects him with the Leibniz-Wolff tradition of recognizing the existence of unconscious representations (An 7:135-7). Kant says the majority of representations that people appeal to in order to explain the complex, discriminatory behaviors of living organisms are “obscure” in a technical sense. Likening the mind to a map Kant goes so far as to say,

The field of sensuous intuitions and sensations of which we are not conscious, even though we can undoubtedly conclude that we have them; that is, obscure representations in the human being (and thus also in animals), is immense. Clear representations, on the other hand, contain only infinitely few points of this field which lie open to consciousness; so that as it were only a few places on the vast map of our mind are illuminated. (An 7:135)

Thus, obscure representations, have no direct or non-inferential awareness but must be posited to explain our fine-grained, differential, and discriminatory capacities. They constitute the majority of the mental representations with which the mind busies itself.

Though Kant does not make it explicit in his discussion of discrimination and consciousness, it is clear that he takes the capacity to discriminate between objects and parts of objects to be ultimately based on sensory representation of those objects. His views on consciousness as differential discrimination intersect with his views on phenomenal consciousness. Because humans are receptive through their sensibility, the ultimate basis on which we differentially discriminate between objects must be sensory. Thus, though Kant seems to take for granted the fact that conscious beings are in states with a particular phenomenal character, it must be the clarity and distinctness of this character that allows a conscious subject to differentially discriminate between the various elements of her environment (see Kant’s discussion of aesthetic perfection in the 1801 Jäsche Logic, 9:33-9 for relevant discussion).

c. Self-Consciousness

As the discussion of unconscious representation indicates, Kant believes we are not directly aware of most of our representations. They are nevertheless, to some degree, conscious, because they allow differential discrimination of elements from the subject’s environment. Kant thinks the process of making a representation clear, or fully conscious, requires a higher-order representation of the relevant representation. In other words, it requires that someone can have representations based on representations. As Kant says, “consciousness is really the representation that another representation is in me” (JL 9:33). Because this higher-order representation is one of another representation in the subject, Kant’s position here suggests that consciousness requires at least the capacity for self-consciousness. This position is reinforced by Kant’s famous claim in the Transcendental Deduction of the Critique of Pure Reason:

The I think must be able to accompany all my representations; for otherwise something would be represented in me that could not be thought at all, which is as much as to say that the representation would either be impossible or else at least would be nothing for me. (B131-2; emphasis in the original)

Kant might give the impression here of saying that for representation to be possible for a subject, the subject must possess the capacity for self-ascribing her representations. If so, then representation, and thus the capacity for conscious representation would depend on the capacity for self-consciousness. Because Kant ties the capacity for self-consciousness to spontaneity (B132, 137, 423) and restricts spontaneity to the class of rational beings, the demand for self-ascription would seem to deny that any non-rational animal (for example, dogs, cats, and birds), could have phenomenal or discriminatory consciousness.

However, there is little evidence to show that Kant endorses the self-ascription condition. Instead, he distinguishes between two distinct modes in which one is aware of oneself and one’s representations—inner sense and apperception (See Ameriks (2000) for extensive discussion). Only the latter form of awareness seems to demand a capacity for self-ascription.

i. Inner Sense

Inner sense is, according to Kant, the means by which we are aware of alterations in our own state. Hence all moods, feelings, and sensations, including such basic alterations as pleasure and pain, are the proper subject matter of inner sense. Ultimately, Kant argues that all sensations, feelings, and those representations attributable to a subject must ultimately occur in inner sense and conform to its form—time (A22-3/B37; A34/B51).

Thus, to be aware of something in inner sense is to be minimally, phenomenally conscious, at least in the case of awareness of sensations and feelings. To say a subject is aware of her own states via inner sense is to say that she has a temporally ordered series of mental states, and is phenomenally conscious of each, though she may not be conscious of the series as a whole. This could still count as a kind of self-awareness, as when an animal is aware of being in pain. But it is not an awareness of subject as a self. Kant himself indicates such a position in a letter to his friend and former student Marcus Herz in 1789.

[Representations] could still (I consider myself as an animal) carry on their play in an orderly fashion, as connected according to empirical laws of association, and thus they could even have influence on my feeling and desire, without my being aware of my own existence [meines Daseins unbewußt] (assuming that I am even conscious of each individual representation, but not of their relation to the unity of representation of their object, by means of the synthetic unity of their apperception). This might be so without my cognizing the slightest thing thereby, not even what my own condition is (C 11:52, May 26, 1789).

Hence, according to Kant, one may be aware of one’s representations via inner sense, but one is not and cannot, through inner sense alone, be aware of oneself as the subject of those representations. That requires what Kant, following Leibniz (1996), calls “apperception”.

ii. Apperception

Kant uses the term “apperception” to denote the capacity for the awareness of some state or modification of one’s self as a state. For one capable of apperception, there is a difference between feeling pain, and thus having an inner sense of it, and apperceiving that one is in pain, and thus ascribing, or being able to ascribe, a certain property or state of mind to one’s self. For example, while a non-apperceptive animal is aware of its own pain and its awareness is partially explanatory of its behavior, like avoidance, Kant construes the animal as incapable of making any self-attribution of its pain. Kant thinks of such a mind as incapable of construing itself as a subject of states, and it is thus unable to construe itself as persisting through changes of those states. This is not necessarily to say an animal incapable of apperception lacks any subject or self. But, at the very least, such an animal would be incapable of conceiving or representing itself in this way (See Naragon (1990); McLear (2011).

Kant considers the capacity for apperception as importantly tied to the capacity to represent objects as complexes of properties attributable to a single underlying entity (for example, an apple as a subject of the complex of the properties red and round). Kant’s argument for this connection is notorious both for its complexity and for its obscurity. The next sub-section will give an overview, though not an exhaustive discussion, of some of Kant’s most important points concerning these matters, as they relate to the issue of apperception.

d. Unity of Consciousness and the Categories

In order to better understand Kant’s views on apperception and unity of consciousness, one must step back and look at the wider context of the argument in which he situates these views. One of the core projects of Kant’s most famous work, the Critique of Pure Reason, is to provide an argument for the legitimacy of a priori knowledge of the natural world. Though Kant’s conception of the a priori is complex, Kant shares one central aspect of his view with his German rationalist predecessors (for example Leibniz (1996), preface), that we have knowledge of universal and necessary truths concerning aspects of the empirical world (B4-5). Those truths include one saying every event in the empirical world has a cause (B231). This tradition tended to explain the possession of knowledge of such universal and necessary truths by appeal to innate concepts which could be analyzed to yield the relevant truths. Kant importantly departs from the rationalist tradition, arguing that not all knowledge of universal and necessary truths is acquired via the analysis of concepts (B14-18). Instead, he says there are some “synthetic” a priori truths that are known on the basis of something other than conceptual analysis. Thus, according to Kant, the activity of pure reason achieves relatively little on its own. All of our ampliative knowledge (knowledge that can’t be directly deduced) that is also necessary and universal consists in what Kant calls “synthetic a priori” judgments or propositions. He then pursues the central question: how is knowledge of such synthetic a priori propositions possible?

Kant’s basic answer to the question of synthetic a priori knowledge involves what he calls the “Copernican Turn.” According to the “Copernican Turn,” the objects of human knowledge must “conform” to the basic faculties of human knowledge—the forms of intuition (space and time) and the forms of thought (the categories).

Kant thus engages in a two-part strategy for explaining the possibility of such synthetic a priori knowledge. The first part consists of arguing that the pure forms of intuition provide the basis for our synthetic a priori knowledge of mathematical truths. Mathematical knowledge is synthetic because it goes beyond mere conceptual analysis to deal with the structure of, or our representation of, space itself. It is a priori because the structure of space is accessible to us as it is merely the form of our intuition and not a real mind-independent thing.

In addition to the representation of space and time, Kant also thinks that possession of a particular, privileged set of a priori concepts is necessary for knowledge of the empirical world. But this raises a problem. How can an a priori concept, which is not itself derived from any particular experience, be nevertheless legitimately applicable to objects of experience? Even more difficult, it is not the mere possibility applying a priori concepts to objects of experience that worries Kant, for this could just be a matter of pure luck. Kant wants more than mere possibility; he wants to show that a privileged set of a priori concepts apply necessarily and universally to all objects of experience and do so in a way that people can know independently of experience.

This brings us to the second part of Kant’s argument, which is directly relevant for understanding Kant’s views on the importance of apperception. Not only must objects of knowledge conform to the forms of intuition, they also must conform to the most basic concepts (or categories) governing our capacity for thought. Kant’s strategy shows how a priori concepts legitimately apply to their objects by being partly constitutive of the objects of representation. This contrasts with the traditional view, according to which the objects of representation were the source or explanatory ground of our concepts (B, xvii-xix). Now, exactly what this means is deeply contested, in part because it is rather unclear what Kant intends by his doctrine of Transcendental Idealism. Does Kant intend that the objects of representation are themselves nothing other than representations? This would be a form of phenomenalism similar to that offered by Berkeley. Kant, however, seems to want to deny that his view is similar to Berkeley’s, asserting instead that the objects of representation exist independently of the mind, and that it is only the way that they are represented that is mind-dependent (A92/B125; compare Pr 4:288-94).

Kant’s strategy attempts to validate the legitimacy of the a priori categories proceeds by way of a “transcendental argument.” It takes the conditions necessary for consciousness of the identity of oneself as the subject of different self-attributed mental states and ties them together with those necessary for grounding the possibility of representing an object distinct from oneself. From those conditions, various properties may be predicated. In this sense, Kant argues that the intellectual representation of subject and object stands and falls together. Kant thus denies the possibility of a self-conscious subject, who could conceptualize and self-ascribe her representations, but whose representations could not represent law-governed objects in space, and thus the material world or ‘nature’ as the subject conceives of it.

Though Kant’s views regarding the unity of the subject are contested, there are several points which can be made fairly clearly. First, Kant conceives of all specific, intellectual activity, including the most basic instances of discursive thought, as requiring what he calls the “original unity of apperception” (B132). This unity, as original, is not itself brought about by some mental act of combining representations, but, as Kant says, is “what makes the concept of combination possible” (B131). It is itself the ground of the “possibility of the understanding” (B131).

Second, the original unity of apperception requires whatever form of self-consciousness characteristically relates to the “I think.” As Kant famously says, “the I think must be able to accompany all my representations” (B131). Moreover, the “I think” essentially involves activity on the part of the subject—it is an expression of the subject’s free activity or “spontaneity” (B132). This means that, according to Kant, only beings capable of spontaneous activity—self-initiated activity that is ultimately traced to causes outside the reach of natural causal laws—are going to be capable of thought in the sense with which Kant is concerned.

Third, and related to the previous point, Kant seems to deny that a subject could attain the kind of representational unity characteristic of thought if her only resources were aggregative methods. Kant makes this point later in the Critique when he says, “representations that are distributed among different beings (for instance, the individual words of a verse) never constitute a whole thought (a verse)” (A 352). William James provides a vivid articulation of the idea: “Take a sentence of a dozen words, and take twelve men and tell to each one word. Then stand the men in a row or jam them in a bunch, and let each think of his word as intently as he will; nowhere will there be a consciousness of the whole sentence” (James (1890), 160). Kant construes consciousness as the “holding-together” of the various components of a thought. He does so in a manner that seems radically opposed to any conception of unitary thought which tries to explain it in terms of some train or succession of its components (Pr 4:304; see Kitcher (2010); Engstrom (2013) for contrasting treatments of this issue).

The exact content of Kant’s argument for the connection between subject and object in the Transcendental Deduction is highly disputed, and it is likely no single reconstruction of the argument can capture all the points Kant supports in the Deduction. At least one strand of Kant’s argument in the first half of the Deduction focuses on Kant’s denial that the unity of the subject and its powers of representational combination could be accounted for by a merely associationist (or Humean) conception of mental combination, sometimes termed his “argument from above” (see A119; Carl (1989); Pereboom (1995)). Kant’s argues (see Pereboom (2009)):

- I am conscious of the identity of myself as the subject of different self-attributions of mental states.

- I am not directly conscious of the identity of this subject of different self-attributions of mental states.

- If (1) and (2) are true, then this consciousness of identity is accounted for indirectly by my consciousness of a particular kind of unity of my mental states.

- Therefore, this consciousness of identity is accounted for indirectly by my consciousness of a particular kind of unity of my mental states. (1, 2, 3)

- If (4) is true, then my mental states indeed have this particular kind of unity.

- This particular kind of unity of my mental states cannot be accounted for by association. (5)

- If (6) is true, then this particular kind of unity of my mental states is accounted for by synthesis by a priori

- Therefore, this particular kind of unity of my mental states is accounted for by synthesis by a priori concepts. (6, 7)

Premise (1) says that I am aware of herself as the subject of different states (or at least able to be so aware). For example, right now I might be hungry as well as sleepy. Previously, I was sleepy and slightly bored. Premise (2) claims I have no immediate or direct awareness of the being which has all of these states. In Kant’s terms, I lack any intuition of the subject of such self-ascribed states, instead having intuition only of the states themselves. Nevertheless, I am aware of all these states as related to a subject (it is I who am bored, hungry, sleepy), and it is in virtue of these connections that I can call one and all of these states mine. Hence, as premise (3) argues, there must be some unity to my mental states which accounts for my (indirect) awareness of their unity. My representations must have some basis for which they go together, and it is the basis for their ‘togetherness’ that explains how I can consider them, one and all, to be mine. Premises (4) and (5) unpack this point, and premise (6) argues that association could not account for such unity (the theory of association was articulated in a particularly influential form by David Hume (1888, Hume (2007)) and the reader should look to that article for relevant background discussion).

Kant’s point, in premise (6) of the above argument, is that forces of association acting on mental representations, whether impressions or ideas, cannot account for either the experience of a train of representations as mine or for the “togetherness” of those representations, both as a single thought or as a series of inferences. Hume argues we have no impression and thus no ensuing idea of an empirical self (Hume (1888), I.iv.6). Kant also accepts this point when he says, “the empirical consciousness that accompanies different representations is by itself dispersed and without relation to the identity of the subject” (B133). By this, Kant means that when we introspect in inner sense, all we ever get are particular mental states, such as boredom, happiness, particular thoughts. We lack any intuition of a subject of those mental states. Hume concludes that the idea of a persisting self which grounds all of these mental states as its subject must be fictitious. Kant disagrees. His contrasting view takes the mineness and togetherness of one’s introspectible mental states as data needing explanation.Because an associative, psychological theory like that of Hume’s cannot explain these features of first-person consciousness (see Hume (1888), III. Appendix), we need to find another theory, such as Kant’s theory of mental synthesis.

Recall that, prior to the argument of the Transcendental Deduction, Kant links the operations of synthesis to possession of a set of a priori concepts, or categories, not derived from experience. Hence, in arguing that synthesis is required to explain the mineness and togetherness of one’s mental states, and by linking synthesis to the application of the categories, Kant argues we could not have the experience of the mineness and togetherness of our mental states without applying the categories.

While this argument is only half of Kant’s argument in the first part of the Deduction, it shows how tightly Kant took the connection to be between the capacities for spontaneity, synthesis and apperception, and the legitimacy of the categories. The other half, by the way, consists of an “argument from below,” and discerns the conditions necessary for the representation of unitary objects, see Pereboom (1995), (2009)According to Kant, there is only one possible explanation of one’s apperceptive awareness of one’s psychological states as one’s own and of all states being related to one another. As the subject of such states, one possesses a spontaneous power for synthesizing one’s representations according to general principles or rules, the content of which is given by pure a priori concepts—the categories. The fact that the categories play such a fundamental role in the generation of self-conscious psychological states is thus a powerful argument demonstrating their legitimacy.

Given that Kant leverages certain aspects of our capacity for self-knowledge in his argument for the legitimacy of the categories, the extent to which he argues for radical limits on our capacity for self-knowledge may be surprising. In the final section, Kant’s arguments concerning our capacity for a priori knowledge of the self and its fundamental features will be made clear. However, the next section will look at one of the central debates in Kant’s interpretation of the role of concepts in perceptual experience.

3. Concepts and Perception

During the discussion of synthesis above, conceptualism was characterized as claiming there is a dependent relation between a subject having conscious sensory experience of an objective world and the repertoire of concepts possessed by the subject and exercised by her faculty of understanding.

As a first pass at sharpening this formulation, understand conceptualism as a thesis consisting of two claims: (i) sense experience has correctness conditions determined by the ‘content’ of the experience, and (ii) the content of an experience is a structured entity whose components are concepts.

a. Content and Correctness

An important background assumption governing the conceptualism debate construes mental states as related to the world cognitively, as opposed to merely causally, if and only if they possess correctness conditions. That which determines the correctness condition for a state is that state’s content (see Siegel (2010), (2011); Schellenberg (2011)).

Suppose, for example, that an experience E has the following content C:

C: That cup is white.

This content determines a correctness condition V:

V: S’s experience E is correct if and only if the cup visually presented to the subject as the content of the demonstrative is white and the content C corresponds to how things seem to the subject to be visually presented.

Here, the content of the experiential state functions much like the content of a belief state to determine whether the experience, like the belief, is or is not correct.

A state’s possession of content thus determines a correctness condition, through which the state can be construed as mapping, mirroring, or otherwise tracking aspects of the subject’s environment.

There are reasons for questioning whether Kant endorses the content assumption articulated above. Kant seems to deny several claims integral to it. First, in various places he explicitly denies that intuition, or the deliverances of the senses more generally, are the kind of thing which could be correct or incorrect (A293–4/B350; An §11 7:146; compare LL 24:83ff, 103, 720ff, 825ff). Second, Kant’s conception of representational content requires an act of mental unification (Pr 4:304; compare JL §17 9:101; LL 24:928), something which Kant explicitly denies is present in an intuition (B129-30; compare B176-7). This is not to deny that Kant uses a notion of “content,” in some other sense, but rather only that he fails to use it in the sense required by interpretations endorsing the content assumption (see Tolley (2014), (2013)). Finally, Kant’s “modal” condition of cognition, that it provides a demonstration of what is really actual rather than merely logically possible, seems to preclude an endorsement of the content assumption (B, xxvii, note; compare Chignell (2014)). However, for the purposes of understanding the conceptualism debate, assume Kant does endorse the content assumption. The question then is how to understand the nature of the content so understood.

b. Conceptual Content

In addition to the content assumption, conceptualism is defined as committed to a conception of intuition’s content being completely composed of concepts. Against this, Clinton Tolley (Tolley (2013), Tolley (2014)) has argued that the immediacy/mediacy distinction between intuition and concept entails a difference in the content of intuition and concept.

If we understand by ‘content’…a representation’s particular relation to an object…then it is clear that we should conclude that Kant accepts non-conceptual content. This is because Kant accepts that intuitions put us in a representational relation to objects that is distinct in kind from the relation that pertains to concepts. I argued, furthermore, that this is the meaning that Kant himself assigns to the term ‘content’. (Tolley (2013), 128)

Insofar as Kant often speaks of the ‘content’ [Inhalt] of a representation as consisting of a particular kind of relation to an object (Tolley (2013), 112; compare B83, B87), Tolley’s proposal thus gives ground for a simple and straightforward argument for a non-conceptualist reading of Kant. However, it does not necessarily prove that the content of what Kant calls an intuition is not something that would be construed by others as conceptual, in a wider sense of that term. For example, both pure—that, this—and complex demonstrative expressions—that color, this person—have conceptual form, and have been proposed as appropriate for capturing the content of experience (McDowell (1996), ch. 3; for discussion see Heck (2000)). Demonstratives are not, in Kant’s terms, ‘conceptual’ since they do not exhibit the requisite generality which, according to Kant, all conceptual representation must.

c. Conceptualism and Synthesis

If it isn’t textually plausible to understand the content of an intuition in conceptual terms, at least as Kant understands the notion of a concept, then what would it mean to say that Kant endorses conceptualism with regard to experience? The most plausible interpretation, endorsed by a wide variety of interpreters, reads Kant as arguing that the generation of an intuition, whether pure or sensory, depends at least in part on the activity of the understanding. On this way of carving things, conceptualism does not consist in the narrow claim that intuitions have concepts as contents or components. Instead, it consists in the broader claim that the occurrence of an intuition depends at least in part on the discursive activity of understanding. The specific activity of understanding is that which Kant calls ‘synthesis,’ the “running through, and gathering together” of representations (A99).

The conceptualist further argues that taking intuitions as generated via acts of synthesis, which are directed by or otherwise dependent upon conceptual capacities, provides some basis for the claim that whatever correctness conditions might be had by intuition must accord with the conceptual synthesis which generated them. This arguably fits well with Kant’s much quoted claim,

The same function that gives unity to the different representations in a judgment also gives unity to the mere synthesis of different representations in an intuition, which, expressed generally, is called the pure concept of understanding. (A79/B104-5)

The link between intuition, synthesis in accordance with concepts, and relation to an object is made even clearer by Kant’s claim in §17 of the B-edition Transcendental Deduction:

Understanding is, generally speaking, the faculty of cognitions. These consist in the determinate relation of given representations to an object. An object, however, is that in the concept of which the manifold of a given intuition is united. (B137; emphasis in the original)

However else we are to understand this passage, Kant here indicates that the unity of an intuition necessary for it to stand as a cognition of an object requires a synthesis by the concept ”object.” In other words, cognition of an object requires that intuition be unified by an act or acts of the understanding.

According to the conceptualist interpretation, one must understand the notion of a representation’s content as a relation to an object, which in turn depends on a conceptually guided synthesis. So we can revise our initial definition of conceptualism to read it as claiming (i) the content of an intuition is a kind of relation to an object, (ii) the relation to an object depends on a synthesis directed in accordance with concepts, and (iii) synthesis in accordance with concepts sets correctness conditions for the intuition’s representation of a mind-independent object.

d. Objections to Conceptualism

At the heart of non-conceptualist readings of Kant stands denial that mental acts of synthesis carried out by understanding are necessary for the occurrence of cognitive mental states of the type which Kant designates by the term “intuition” [Anschauung]. Though it is controversial as to what might be considered the “natural” or “default” reading of Kant’s mature critical philosophy, there are at least four considerations which lend strong support to a non-conceptualist interpretation of Kant’s mature work.

First, Kant repeatedly and forcefully states that in cognition there is a strict division of cognitive labor—objects are given by sensibility and thought via understanding:

Objects are given to us by means of sensibility, and it alone yields us intuitions; they are thought through the understanding, and from the understanding arise concepts (A19/B33; compare A50/B74, A51/B75–6, A271/B327).

As Robert Hanna has argued, when Kant discusses the dependence of intuition on conceptual judgment in the Analytic of Concepts, he specifically talks about cognition rather than what others would consider to be perceptual experience (Hanna (2005), 265-7).

Second, Kant characterizes the representational capacities characteristic of sensibility as more primitive than those characteristic of understanding, or reason, and he characterizes those capacities as a plausible part of what humans share with the rest of the animal kingdom (Kant connects the possession of a faculty of sensibility to animal nature in various places, for example A546/B574, A802/B830; An 7:196). For example, Kant’s distinction between the faculties of sensibility and understanding seems intended to capture the difference between the “sub-rational” powers of the mind that is shared with non-human animals and the “rational or higher-level cognitive powers” that are special to human beings. (Hanna (2005), 249; compare Allais (2009); McLear (2011))

If one were to deny that, according to Kant, sensibility alone is capable of producing mental states cognitive in character, then, it would seem that any animal which lacks a faculty of understanding would thereby lack any capacity for genuinely perceptual experience. The mental lives of non-rational animals would thus, at best, consist of non-cognitive sensory states causally correlated with changes in the animal’s environment. Aside from an unappealing and implausible characterization of the animals’ cognitive capacities, this reading also faces textual hurdles (for relevant discussion of some of the issues in contemporary cognitive ethology see Bermúdez (2003); Lurz (2009); Andrews (2014), as well as the papers in Lurz (2011)). Kant is on record in various places as saying that animals have sensory representations of their environment (CPJ 5:464; LM 28:449; compare An 7:212), that they have intuitions (LL 24:702), and that they are acquainted with objects though they do not cognize them (JL 9:64–5) (see Naragon (1990); Allais (2009); McLear (2011)).

Hence, if Kant’s position is that synthetic acts carried out by the understanding are necessary for the cognitive standing of a mental state, then Kant is contradicting fundamental elements of his own position in crediting intuitions or their possibility to non-rational animals.

Third, any position which regards perceptual experience as dependent upon acts of synthesis carried out by the understanding would presumably also construe the ‘pure’ intuitions of space and time as dependent upon acts of synthesis (see Longuenesse (1998), ch. 9; Griffith (2012)). However, Kant’s discussion of space, and, analogously, time, in the third and fourth arguments (fourth and fifth in the case of time) of the Metaphysical Exposition of Space in the Transcendental Aesthetic seems incompatible with such a proposed relation of dependence.

Kant’s point in the third and fourth arguments of the Metaphysical Exposition of space and time is that no finite intellect could grasp the extent and nature of space as an infinite whole via a synthetic process involving movement from representation of a part to representation of the whole. If the unity of the forms of intuition were itself something dependent upon intellectual activity, then this unity would necessarily involve the discursive, though not necessarily conceptual, running through and gathering together of a given multiplicity (presumably of different locations or moments) into a combined whole. Kant believes this is characteristic of synthesis generally (A99).

But Kant’s arguments in the Metaphysical Expositions require the fundamental basis of the representation of space and time does not proceed from a grasp of the multiplicative features of an intuited particular to the whole with those features. Instead, the form of pure intuition constitutes a representational whole that is prior to that of its component parts (compare CJ 5:407-8, 409).

Hence, Kant’s position is that the pure intuitions of space and time possess a unity wholly different from that given by the discursive unity of understanding (whether in conceptual judgment or the intellectual with imaginative synthesis of intuited objects). The unity of aesthetic representation—characterized by forms of space and time—has a structure in which the representational parts depend upon the whole. The unity of discursive representation—representation where the activity of understanding is involved—has a structure in which the representational whole depends upon its parts (see McLear (2015)).

Finally, there has been extensive discussion on the non-conceptuality of intuition in the secondary literature on Kant’s philosophy of mathematics. For example, Michael Friedman has argued that the expressive limitations of prevailing logic in Kant’s time required the postulation of intuition as a form of singular, non-conceptual representation (Friedman (1992), ch. 2; Anderson (2005); Sutherland (2008)). In contrast to Friedman’s view, Charles Parsons and Emily Carson argued that the immediacy of intuition, both pure and empirical, should be construed in a ‘phenomenological’ manner. Space in particular is understood on their interpretation as an original, non-conceptual representation, which Kant takes to be necessary for the demonstration of the real possibility of constructed, mathematical objects as required for geometric knowledge (Parsons (1964); Parsons (1992); Carson (1997); Carson (1999); compare Hanna (2002). For a general overview of related issues in Kant’s philosophy of mathematics, see Shabel (2006) and the works cited therein at p. 107, note 29.)

Ultimately, however, there are difficulties assessing whether Kant’s philosophy of mathematics can have relevance for the conceptualism debate. It is not obvious whether intuition must be non-conceptual in accounting for mathematical knowledge is incompatible with claiming that intuitions themselves are dependent upon a conceptually-guided synthesis.

The non-conceptualist reading clearly commits to allowing that sensibility alone provides, perhaps in a very primitive manner, objective representation of the empirical world. Sensibility is construed as an independent cognitive faculty, which humans share with other non-rational animals, and which is the jumping-off point for more sophisticated, conceptual representation of empirical reality.

The next and final section looks at Kant’s views regarding the nature and limits of self-knowledge and the ramifications of this for traditional rationalist views of the self.

4. Rational Psychology and Self-Knowledge

Kant discusses the nature and limits of our self-knowledge most extensively in the first Critique, in a section of the Transcendental Dialectic called the “Paralogisms of Pure Reason.” Here, Kant is concerned to criticize the claims of what he calls “rational psychology.” Specifically, he is concerned about the claim that we can have substantive, metaphysical knowledge of the nature of the subject, based purely on an analysis of the concept of the thinking self. As Kant typically puts it:

I think is thus the sole text of rational psychology, from which it is to develop its entire wisdom…because the least empirical predicate would corrupt the rational purity and independence of the science from all experience. (A343/B401)

There are four “Paralogisms.” Each argument is presented as a syllogism, consisting of two premises and a conclusion. According to Kant, each argument is guilty of an equivocation on a term common to the premises, such that the argument is invalid. Kant’s aim, in his discussion of each Paralogism, is to diagnose the equivocation, and explain why the rational psychologist’s argument ultimately fails. In so doing, Kant provides a great deal of information about his own views concerning the mind (See Ameriks (2000) for extensive discussion). The argument of the first Paralogism concerns knowledge of the self as substance; the second, the simplicity of the self; the third, the numerical identity of the self; and the fourth, knowledge of the self versus knowledge of things in space.

a. Substantiality (A348-51/B410-11)

Kant presents the rationalist’s argument in the First Paralogism as follows:

- What cannot be thought otherwise than as subject does not exist otherwise than as subject, and is therefore substance.

- Now a thinking being, considered merely as such, cannot be thought of as other than a subject.

- Therefore, a thinking being also exists only as such a thing, i.e., as substance.

Kant’s presentation of the argument is rather compressed. In more explicit form we can put it as follows (see Proops (2010)):

- All entities that cannot be thought of as other than a subjects are entities that cannot exist otherwise than as subjects, and therefore are substances. (All M are P)

- All entities that are thinking beings are entities that cannot be thought otherwise than as subjects. (All S are M)

- Therefore, all entities that are thinking beings are entities that cannot exist otherwise than as subjects, and therefore are substances (All S are P)

The relevant equivocation is in the term that occupies the ‘M’ place in the argument— “entities that cannot be thought otherwise than as subjects”. Kant specifically locates the ambiguity in the use of the term “thought” [Das Denken], which he claims concerns an object in general in the first premise. Thus, “thought” could be given in a possible intuition. In the second premise, the use of “thought” is supposed to apply only to a feature of thought and, thus, not to an object of a possible intuition (B411-12).

While it isn’t obvious what Kant means by this claim, it could be that. Kant takes the first premise to make a claim about the objects of thought. They exist as an independent subject or bearer of properties and cannot be conceived of as anything else. This is thus a metaphysical claim about what kinds of objects could really exist, which explains Kant’s reference to an “object in general” that could be given in intuition.

In contrast, premise (2) makes a merely logical claim concerning the role of the representation <I> in a possible judgment. Kant says one cannot use representation <I> in any place other than upon the subject. For example, while I can make the claim “I am tall,” I would make no sense to claim “the tall is I.”

Against the rational psychologist, Kant argues that one cannot make any legitimate inference from the conditions under which representation <I> may be thought, or employed in a judgment, to the status of the ‘I’ as a metaphysical subject of properties. Kant makes this point explicit when he says,

The first syllogism of transcendental psychology imposes on us an only allegedly new insight when it passes off the constant logical subject of thinking as the cognition of a real subject of inherence, with which we do not and cannot have the least acquaintance, because consciousness is the one single thing that makes all representations into thoughts, and in which, therefore, as in the transcendental subject, our perceptions must be encountered; and apart from this logical significance of the I, we have no acquaintance with the subject in itself that grounds this I as a substratum, just as it grounds all thoughts. (A350)

Kant thus argues that one should differentiate between different conceptions of “substance” and the role they play in thoughts concerning the world.

Substance0:

x is a substance0 if and only if the representation of x cannot be used as a predicate in a categorical judgment

Substance1:

x is a substance1 if and only if its existence is such that it can never inhere, or exist, in anything else (B288, 407)

The first conception of substance is merely logical or grammatical. The second conception is explicitly metaphysical. Finally, there is an even more metaphysically demanding usage of “substance” that Kant employs.

(Empirical) Substance2:

x is a substance2 if and only if it is a substance1 that persists at every moment (A144/B183, A182)

According to Kant, the rational psychologist attempts to move from claims about substance0 to the more robustly metaphysical claims characteristic of conceptions and uses of substance1 and substance2. However, without further substantive assumptions, which go beyond anything given in an analysis of the concept <I>, no legitimate inference can be made from our notion of a substance0 to either of the other conceptions of substance.

Because, Kant denies that humans have any intuition, empirical or otherwise, of themselves as subjects, they cannot come to have any knowledge concerning what we are in terms of beings either substance1 or substance2. At least they cannot do so by reflecting on the conditions of thinking of themselves using first-person concepts. No amount of introspection or reflection on the content of the first-person concept <I> will yield such knowledge.

b. Simplicity (A351-61/B407-8)

Kant’s discussion of the proposed metaphysical simplicity of the subject largely depends on points he made in the previous Paralogism concerning its proposed substantiality. Kant articulates the Second Paralogism as follows:

- The subject, whose action can never be regarded as the concurrence of many acting things, is simple. (All A is B)

- The self is such a subject. (C is A)

- Therefore, the self is simple. (C is B)

Here, the equivocation concerns the notion of a “subject.” Kant’s point, as with the previous Paralogism, is that, from the fact that one’s first-person representation of the self is always a grammatical or logical subject, nothing follows concerning the metaphysical status of that representation’s referent.

Of perhaps greater interest in this discussion of the Paralogism of simplicity is Kant’s analysis of what he calls the “Achilles of all dialectical inferences” (A351). According to the Achilles argument, the soul or mind is known to be a simple, unitary substance, because only such a substance could think unitary thoughts. Called the “unity claim” (see Brook (1997)), it says:

(UC):

If a multiplicity of representations are to form a single representation, they must be contained in the absolute unity of the thinking substance. (A352)

Against UC, Kant argues that there is no reason to think the structure of a thought, as a complex of representations, isn’t mirrored in the complex structure of an entity that thinks thoughts. UC is not analytic, which is to say that there is no contradiction entailed by its negation. UC also fails to be a synthetic a priori claim, in that it follows neither from the nature of intuition’s forms, nor from categories. Hence, UC could only be shown to be true empirically, and because people have no empirical intuition of the self, people have no basis for thinking that UC must be true (A353).

Kant here makes a point similar to contemporary, functionalist accounts of the mind (see Meerbote (1991); Brook (1997)). Mental functions, including the unity of conscious thought, are consistent with a variety of different media in which functions are realized. Kant’s says there is no contradiction in thinking that a plurality of substances might succeed in generating a single, unified thought. Hence, we cannot know that the mind is such that it must be simple in nature.

c. Numerical Identity (A361-66/B408)

Kant articulates the Third Paralogism as follows:

- What is conscious of the numerical identity of its Self in different times, is, to that extent, a person. (All C is P)

- Now, the soul is conscious of the numerical identity of its Self in different times. (S is C)

- Therefore, the soul is a person. (S is P)

Rational psychologists’ interest in establishing the personality of the soul or mind stems from the importance of proving that not only would the mind persist after the destruction of its body, but also that this mind would be the same person as before, not just some sort of bare consciousness or worse (for example, existing only as a “bare monad”).

Kant here makes two main points. First, the rational psychologist cannot infer from the sameness of the first-person representation (the “I think”) or across applications of it in judgment to any conclusion concerning the sameness of the metaphysical subject referred to by that representation. Kant thus again makes a functionalist point. The medium in which a series of representational states inheres may change over time, and there is no contradiction in conceiving of a series of representations as being transferred from one substance to another (A363-4, note).

Second, Kant argues that we can be confident of the soul’s possession of personality by virtue of apperception’s persistence. The relevant notion of “personality” here distinguishes between a rational being and an animal. While the persistence of apperception (the persistence of the “I think” as being able to attach to all of one’s representations) does not provide an apperceiving subject with any insight into the true metaphysical nature of the mind, it does provide evidence of the soul’s possession of an understanding. Animals, by contrast, do not possess an understanding but, at best, according to Kant, only an analogue thereof. As Kant says in the Anthropology,@

That man can have the I among his representations elevates him infinitely above all other living beings on earth. He is thereby a person […] that is, by rank and worth a completely distinct being from things that are the same as reason-less animals with which one can do as one pleases. (An 7:127, §1)

Hence, so long as a soul possesses the capacity for apperception, it will signal the possession of an understanding, and thus serves to distinguish the human soul from that of an animal (see Dyck (2010), 120).

d. Relation to Objects in Space (A366-80/B409)

Finally, the Fourth Paralogism concerns the relation between awareness of one’s own mind and one’s awareness of other objects distinct from oneself. Thus, it also deals with one’s mind and awareness of space. Kant describes the Fourth Paralogism as follows:

- What can be only causally inferred is never certain. (All I is not C)

- The existence of outer objects can only be causally inferred, not immediately perceived by us. (O is I)

- Therefore, we can never be certain of the existence of outer objects. (O is not C)

Kant locates the damaging ambiguity in the conception of “outer” objects. This is puzzling because it doesn’t play the relevant role as middle term in the syllogism. But Kant is quite clear that this is where the ambiguity lies and distinguishes between two distinct senses of the “outer” or “external”:

Trancendentally Outer/External:

A seperate existence, in and of itself.

Empirically Outer/External:

An existence in space.

Kant’s point here is that all appearances in space are empirically external to the subject who perceives or thinks about them, while nevertheless being transcendentally internal. Such spatial appearances do not have an entirely independent metaphysical nature, because their spatial features depend at least in part on our forms of intuition.

Kant then uses this distinction not only to argue against the assumption of the rational psychologist that the mind is better known than any object in space (famously argued by Descartes), but also against those forms of external world skepticism championed by Descartes and Berkeley. Kant identifies Berkeley with what he calls “dogmatic idealism” and Descartes with what he calls “problematic idealism” (A377). He defines them thus:

Problematic Idealism:

We cannot be certain of the existence of any material body.

Dogmatic Idealism: