Property

Concepts of property are used to describe the legal and ethical entitlements that particular people or groups have to use to manage particular resources. Beyond that most general definition of ‘property’ however, philosophical controversy reigns.

Political and legal philosophers disagree on what types of entitlements are essential elements of property, and on the shape and nature of the resultant property entitlements. Indeed, philosophers even disagree on whether it makes sense to talk, in abstraction from a specific legal context, of concepts of property at all. These theoretical controversies are mirrored in practice and law. Cases are determined and conflicts are resolved – or fomented, as the case may be – by the different ideas of property that claimants, judges, legislators and ordinary people recognise and deploy. These controversies are compounded when property concepts are used in application not only to the obvious cases of land and chattels (that is, movable items of property like chairs and cars), but to airspace, airwaves, inventions, information, corporate stock, reputations, fishing rights, brand names, labour, works of art and literature, and more.

Over the last century of political and legal thought, there have been two major – and very different –property-concepts: Bundle Theory and Full Liberal Ownership. Bundle Theory holds that property is a disparate ‘bundle’ of legal entitlements, or ‘sticks’ as they are metaphorically termed. What property a person holds in any given case is determined by the specific entitlements granted by the law to that person. According to Bundle Theory there is no prior idea of property that the law reflects, or that guides the adjudication of cases. The central reason supporting Bundle Theory is the dizzying diversity of property entitlements in law: applying to myriad sorts of resources, regulated in innumerable ways, subject to different sorts of taxation and differing across jurisdictions.

Other theorists, however, have argued that despite the complexity of certain cases of property in law, the idea of property carries genuine content across many contexts and jurisdictions – especially in application to land and chattels. Far from having no substance, the idea of Full Liberal Ownership gave property a detailed and comprehensive meaning: property includes the full gamut of rights to: (a) use the owned resource, (b) exclude others from entering it, and, (c)alienate it (that is, to sell it to someone else).

Yet if Bundle Theory can be faulted as being too nebulous to be correct, some property theorists have argued that Full Liberal Ownership falls into the opposite error, and is too simple and stringent to explain the lived detail of property entitlements. Rejecting both these theories, these theorists have developed diverging accounts of property, arguing that one feature or other – exclusion, use, power, immunity or remedy – is the essential hallmark of property.

This article surveys the major types of contemporary property theories, and the philosophical arguments offered in support of them. The nature of such property concepts carries consequences for the ethical justifications of various property regimes. Several of the more important consequences will be noted in this article, but not pursued in any detail.

Table of Contents

- Preliminaries

- Bundle Theory

- Full Liberal Ownership

- The General Idea of Private Property: The Integrated Theory

- Exclusion: Trespass-Based Theories

- Use: Harm-Based Theories

- Power-Based Theories: The Question of Alienation

- Immunity-Based Theories

- Remedy-Based Theories

- Examples of Cross-Cutting Theories

- Socialist and Egalitarian Property

- References and Further Reading

1. Preliminaries

With his characteristic shrewdness, Nietzsche once observed that it is hard to define concepts that have a history. Whatever else may be said of it, property has a history; forms of private property in land date back at least ten millennia, and private property in chattels (movable objects of property like tools and clothes) was present in the Stone Age. With Nietzsche’s point in mind, then, three general remarks on property’s conceptual ambiguities are worth making.

First, the term ‘property’ may refer to the proprietorial entitlements of an owner (Bob has property in that car) or it may refer to the thing that is owned itself (That car is Bob’s property). Lawyers and philosophers tend to be wary of the latter use, primarily because it can distract attention from the significance of the entitlements involved. That is, if we speak about Bob’s car as being his property, then we might be inclined to think that property is all about Bob’s relation to his car, rather than being about the duties everyone owes Bob with respect to his car. If we say that Bob has property in his car, then it is a little clearer that property is about legal and ethical entitlements, and not merely about a physical thing. That said however, using ‘property’ to refer only to entitlements and not to things carries the danger of forgetting that ordinary people and sometimes even lawmakers may be using the term in its second application (Wenar 1997). With this in mind, this article will use the term in both its meanings; context should at any point make clear which is intended.

Second, property comes in at least three different basic forms: private, collective and common. Private property grants entitlements to a resource to particular individuals, collective property vests them in the state, and common property enfranchises all members of a community. Most contemporary debate on the nature of property surrounds the concept of private property, and this will be the focus of the article. Reflecting this, the term ‘property’ typically will stand for private property, except in the specific sections dealing with common property and collective property (§ 6.1 and §11). Reference to one of these three types of property is often used to characterise types of economic and political regimes. For instance, liberalism may be characterised by private property, socialism by collective property, and certain forms of anarchism and communitarianism by the use of common property. However, it is important to be aware that such characterisations are made on the basis of the predominant form of property in the regime, as no regime relies exclusively on just one form of property. Certain resources seem to be more amenable to one type of property entitlement than another: air as common property, toothbrushes as private property, and artillery as collective property, for example.

Third, actual property entitlements – in law and custom alike – tend to be highly complex, so caution is advisable when philosophical (armchair) theories of property are used to characterise actual property entitlements. The effort to categorize and clarify can distort important features of property that lie within its complexities.

2. Bundle Theory

Bundle Theory is not so much a property-concept as it is the idea that ‘property’ is not really a proper concept at all. Bundle Theory states that there is no pre-existing, well-defined and integrated concept of property that guides – or should guide – our understanding of property-entitlements, or the creation or interpretation of property-entitlements in law. Instead, the law grants specific entitlements of people to things. The property that a person holds in any given instance is simply the sum total of the particular entitlements the law grants to her in that situation. These particular entitlements are metaphorically termed ‘sticks’, and the property that a person holds is thus the particular bundle of sticks the law grants to them in the given instance. Changes to law can alter property entitlements by adding or removing particular sticks from the bundle. Also, several people may have property-entitlements in one resource, as the sticks are spread amongst them, each person with his own bundle. In such cases, Bundle Theory says, it is meaningless to try to determine who the real owner is; each person simply has the entitlements the law grants to them.

There are three main arguments for Bundle Theory. The first argument is conceptual and dates back to Wesley Hohfeld’s path-breaking analysis of rights. Hohfeld (1913) argued that entitlements in law could be broken down into their constituent parts – the basic building-blocks of which more complex legal entitlements are constructed. He termed these basic entitlements ‘jural relations’. In all, Hohfeld described eight jural relations, four of which are important for our purposes here:

Liberty/Privilege: Person A has a liberty to do X with respect to another person B when A has no duty to B not to do X. For example, in an ordinary case Annie will have a liberty (with respect to some other beach-goer Bob) to swim at a public beach if she is not under any duty to Bob not to swim at the beach.

Claim-right: Person A has a claim on another person B to do X when B is under a duty owed to A to perform X. For instance, Annie has a claim-right that Bob not hit her – a claim that correlates with Bob’s duty to refrain from hitting Annie.

Power: Person A has a power over person B with respect to X when A can alter B’s liberties and claim-rights with respect to X. For instance, when Annie alters Bob’s liberties by waiving her claim-right that he not kiss her, she exercises her power to dissolve Bob’s prior duty and so to grant him a liberty. Promising, waiving and selling are all examples of using powers because they all involve the agent in question altering in some way the duties of other people.

Immunity: Person A has an immunity against a person B with respect to X if B cannot alter A’s claims or liberties with respect to X. For instance, if Annie has an immunity against Bob with respect to her freedom of association, then Bob cannot impose new duties on her to refrain from associating (with Charles, say).

Powers and immunities are sometimes called ‘second-order’ jural relations, because they modify or protect first-order jural relations like liberties and claims-rights. For example, when Annie waives (that is, gives up or relinquishes) Bob’s duties not to kiss her, she uses a second-order jural relation (a power) to create in Bob a first-order jural relation (a liberty). As Hohfeld argued, any given right may be broken down into these common denominators – these liberties, claims, immunities and powers. In particular, upon analysis, property may be so divided. Property usually contains some liberties (e.g. to use and possess), some claim-rights (e.g. that others not trespass), some immunities (e.g. that others cannot simply dissolve their duties not to trespass) and some powers (e.g. to sell the owned object). Hohfeld’s analysis demonstrated that property was not as simple an idea as it might first appear. Contrary to popular opinion, property was not a relationship with a thing, but a myriad of jural relations with an indefinite number of other people with respect to a thing. It was not itself a simple entitlement, but rather a consolidated entitlement made up of more simple constituents.

Hohfeld’s analysis did not require adopting the Bundle Theory thesis that there was no integrity or determinate content to the concept of property. One could, as many have since done, hold that property was a specific group of certain sorts of Hohfeldian jural relations. However, Hohfeld’s system laid the conceptual groundwork for Bundle Theory’s stance. Once property could be conceptually dissected into its constituent parts, the door was open for the disintegration of the concept itself. The positive reason for performing such disintegration was supplied by the second argument for Bundle Theory: the complexity of actual proprietorial entitlements in law.

At least by the arrival of the twentieth century, if not much earlier, property entitlements had become enormously complex. Property entitlements were applied to myriad different entities: to airspace, airwaves, inventions, information, fugacious resources (flowing resources like water and oil), riparian land (land bordering rivers), fisheries, wild animals, broadcast rights, mining rights, brand names, labour, works of art and literature, corporate stock, options, reputations, and so on and on. It was difficult to believe that the same cluster of Hohfeldian jural relations were enjoyed by holders of property over all these diverse resources. Furthermore, all of these sorts of property were subject to a wide variety of regulation and taxation measures, all of which might change from country to country, if not state to state. Worse still, many types of property had multiple persons with separate proprietorial entitlements in them; trusts, easements, and common property entitlements all allowed many people to have property in the one resource. While there may have been sense in using a determinate, integrated idea of property in the eighteenth century, it was argued, such a simplistic notion was outmoded (Grey 1980). Faced with the breathtaking variety of existing proprietorial entitlements, the sensible response was to abandon talk of ‘property’ altogether and refer directly to the specific Hohfeldian jural relations – the particular bundle of sticks – held by a given person in a given instance.

The third argument for Bundle Theory’s proposed disintegration of property is an explicitly normative one: that is, it derives from political and ethical theory. Those advocating an integrated idea of property tended to be drawn toward a very strong notion of property: Full Liberal Ownership (see §3 below). This concept of property appeared to leave precious little space for taxation or rates, and so seemed to present a potentially powerful obstacle to the usual schemes for funding basic state institutions, developing public goods, or alleviating poverty. Similarly, Full Liberal Ownership conflicted with state regulation of property, and so opposed environmental limitations on the use of land. With such concerns in mind, some property theorists concluded that any defensible proprietorial entitlements must be fashioned in accord with social justice and environmental commitments, rather than determined by a prior declaration of the essential nature of property (Singer 2000; Freyfogle 2003). Property entitlements are a product of policy and legislation, it was argued, not a conceptual or normative force guiding it. If this is right, then Bundle Theory is a more accurate depiction of the proper nature of property.

For conceptual, descriptive and normative reasons, then, Bundle Theory aimed to disintegrate the concept of property. In its thinking, the state should decide which entitlements to confer on an individual in any given case; that bundle of sticks thereafter constitutes the property that individual holds. There is no prior concept of property determining its bounds.

3. Full Liberal Ownership

If Bundle Theorists had expected the idea of property to fall into disuse however, they were mistaken; the idea of property continued to be invoked in lay, legal and theoretical discourse. Indeed, ordinary people seemed to be able to use their rough-and-ready ideas of property to workably navigate their way through the complex legal world around them. With such considerations as these in mind, philosophers and legal commentators increasingly began to question Bundle Theory’s disintegration of the concept. While the complexity and flexibility of property in some exotic applications could not be questioned, in other more familiar applications it appeared to have an adequate consistency. This was particularly true with respect to chattels like umbrellas, toothbrushes and cars. Far from having no content, it was observed, property entitlements to such objects displayed a profound homogeneity across jurisdictions and political regimes.

Emerging out of this literature, but with countless historical forebears, was a comprehensive concept of property: Full Liberal Ownership. The ringing tones of legal theorist William Blackstone in his 1776 Commentaries on the Laws of England are often used to encapsulate Full Liberal Ownership. In the opening lines of the second book Blackstone declares property to be:

that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the right of any other individual in the universe.

Less poetically, but rather more informatively, in 1961 the legal scholar A. M. Honoré set down what he viewed as the eleven ‘standard incidents’ of ownership:

- The right to possess: to have exclusive physical control of a thing;

- The right to use: to have an exclusive and open-ended capacity to personally use the thing;

- The right to manage: to be able to decide who is allowed to use the thing and how they may do so;

- The right to the income: to the fruits, rents and profits arising from one’s possession, use and management of the thing;

- The right to the capital: to consume, waste or destroy the thing, or parts of it;

- The right to security: to have immunity from others being able to take ownership of (expropriating) the thing;

- The incident of transmissibility: to transfer the entitlements of ownership to another person (that is, to alienate or sell the thing);

- The incident of absence of term: to be entitled to the endurance of the entitlement over time;

- The prohibition on harmful use: requiring that the thing may not be used in ways that cause harm to others;

- Liability to execution: allowing that the ownership of the thing may be dissolved or transferred in case of debt or insolvency; and,

- Residuary character: ensuring that after everyone else’s entitlements to the thing finish (when a lease runs out, for example), the ownership returns to vest in the owner.

With one modification, this list conveys the now popular idea of Full Liberal Ownership. The modification is the rejection by later property theorists of Incident Nine, the prohibition on harmful use. While it is of course agreed that an owner may not use her property in ways that harm others, most theorists see this constraint as a reflection of a prior and ongoing duty all people have not to harm others, and so as not a feature of property per se.

Honoré’s comprehensive listing of these incidents does not in itself confute Bundle Theory. Indeed, as it turned out, Honoré’s list proved a helpful resource for Bundle Theorists; it usefully described the types of sticks that may or may not be present in a proprietor’s bundle. A proprietor may have the incident of income, but not the incident of management, for example, or vice versa. Yet two points can be made about Honoré’s list that do challenge Bundle Theory.

The first point is conceptual: while modifications in many cases may occur, Honoré’s list showed it was possible for there to be a ‘standard case’ of property. His list of incidents was not asserted to be a strict definition of property, demarcating its necessary-and-sufficient conditions. Rather, it outlined the basic features of the concept of property in a manner evocative of Wittgenstein’s idea of ‘family resemblance’. Even if Bundle Theory was right that there was no strict essence of property, the concept nevertheless displayed an array of central characteristics by which it could be recognized and utilized. Furthermore, with this standard set down, other more esoteric types of property could be modeled upon it by analogy.

The second point is the actual existence, in law and custom, of the full complement of Honoré’s property-incidents, in chattels at least, in many places across the globe. As Honoré argued with respect to umbrellas; and others did similarly with respect to automobiles and other moveables, property in such items very often amounts to Full Liberal Ownership. In application to chattels at least, there is – contrary to the claims of Bundle Theory – a striking consistency in the meaning of property.

Even with these two points acknowledged, however, Full Liberal Ownership has seemed to many theorists an overly comprehensive account of private property. While it may be difficult to deny the consistency in proprietorial entitlements over chattels, the problem cases put forward by Bundle Theory remain. Indeed, recent work on common property rights (such as the shared right to hunt a local wood, or fish a local stream) has expanded the array of property cases that struggle to fit the individualist Full Liberal Ownership mould. Likewise, the tension between the requirements of Full Liberal Ownership and political commitments to social justice and environmental sustainability are as relevant as ever. Indeed, the oft-cited declaration of Blackstone above – when set in the context of his famous Commentaries themselves – draws our attention to both the intuitive appeal of Full Liberal Ownership and its surprisingly limited application in the real world in the face of environmental problems and issues of social justice. For as any reader of the Commentaries quickly discovers, Blackstone’s book on property teems with all manner of exotic and overlapping proprietorial rights – in fishing, hunting, travel, foraging, pasturing, recreation and digging for turf or peat. Full Liberal Ownership hardly makes an appearance in the Commentaries even as an ideal type. In the last analysis, then, Full Liberal Ownership seems to be honored more in the breach than in the observance.

Much of the recent work in property theory can be seen as an attempt to navigate between the two poles of Full Liberal Ownership and Bundle Theory, aiming to provide an account that preserves the conceptual integrity of the former while allowing some of the descriptive and normative flexibility of the latter.

There are a variety of theoretical options open to the property theorist attempting such navigation. They may adopt a broader concept of property and then envisage Full Liberal Ownership as one conceptualization (that is, specification) of that larger idea (Waldron 1985). They may adopt a continuum concept of property, where ownership sits as the limit case at the very top of a spectrum of property entitlements, with lesser entitlements located further down the spectrum (Harris 1996). Or they may advance additional concepts of property that sit alongside ownership and aim to cover the cases it is perceived to miss (Breakey 2011). Perhaps the commonest response, however, is simply to relax a strict necessary-and-sufficient-conditions reading of Honoré’s incidents, and consider the usual elements located within the general idea of property.

4. The General Idea of Private Property: The Integrated Theory

Taking a broader perspective than Honoré, many contemporary property theorists accept a three-part approach to property. The general idea of private property, it is held, consists of the following three elements:

Exclusion: others may not enter or use the resource;

Use: the owner is free to use and consume the resource;

Management and Alienation: the owner is free to manage, sell, gift, bequeath or abandon the resource.

On this account, property owners are expected to have some level of each of these three types of entitlements. Full Liberal Ownership will emerge as the limit case of private property, arising when a property-holder has the maximum possible entitlement on the three dimensions of exclusion, use and alienation. Lesser types of property are still possible, provided they contain some threshold amount of these three elements.

This view is thus less absolutist and less comprehensive than Full Liberal Ownership; private property may be regulated or taxed, yet it still displays the signature properties of exclusion, use and alienability—it remains property. Equally though, this concept of property – Integrated Theory, as some have called it – departs from Bundle Theory by viewing property as a consolidated concept (Mossoff 2003). Whether we express property’s entitlements under the three categories of exclusion, use and alienation, or through Hohfeld’s jural relations or Honoré’s incidents, the thought is that its components integrate together to create a united sum that is larger than its parts. Contrary to the claims of Bundle Theory, it is argued, property is a larger, organic whole; the elements of property are not easily detached one from another, and a legal regime cannot simply pick and choose from them at will. Use, exclusion and alienation fit together like three pieces of a puzzle.

In what ways does Integrated Theory hold the elements of property to be conceptually linked? Expressing these conceptual links in terms of Honoré’s incidents, it seems reasonable to think that use includes and requires possession, and that management includes both of these. After all, one cannot manage a property without being able to use it, and one cannot use it without being able to enter it or hold it. Furthermore, income in the form of fruits, rents and profits seems to be a natural result of a property-holder gaining the benefits of possession, use and management respectively (Attas 2007). Likewise, immunities from expropriation are linked to all these incidents. One can’t manage or gain income from a resource if others can simply dissolve all one’s entitlements to it and use it for free.

As such, it is no easy matter for a property bundle on the one hand to include management and on the other to exclude income or immunity. The point may be argued similarly with respect to Hohfeld’s jural relations. While it is, strictly speaking, conceptually possible to distinguish between claim-rights against other’s trespass, liberties of use, and powers of management, it seems fair to say that such relations nevertheless sit very naturally alongside one another. It is difficult to understand what the point would be of having just one of these entitlements without having one or both of the others (Merrill 1998). (This inter-linkage explains, after all, why Hohfeld’s analysis was so groundbreaking, and why law students often struggle to grasp it: ordinary language naturally bunches together the elements that Hohfeld carefully distinguished.) As such, the disintegrated notion of property conjured up by Bundle Theory appears misleading. Analogizing to physics, while it might be true that atoms are made up of protons, neutrons and electrons, this does not mean that it is advisable to try splitting them into these component parts, or that it is possible to reconfigure them in any given alternative arrangement.

Even if it is accepted that there are deep conceptual and practical ties between the elements of property, however, the question may still arise: Which, if any, of the three elements above is the quintessential mark – the essential feature – of property? As the next several sections explain, many property theorists have departed from the Integrated Theory in holding that the essence of property is one or other of the three elements of exclusion, use and alienability – and some property theorists have looked even further afield. The question is not merely a theoretical one. The law often needs to determine whether a given regulation is or is not a violation of the property right – whether it is, for instance, a taking in respect of the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution. For such purposes, the question of the essence of property is pivotal. Is it found within exclusion, use, powers of alienation, or some further element?

5. Exclusion: Trespass-Based Theories

As Blackstone’s talk of ‘total exclusion’ suggests, perhaps the most intuitive answer to the question of property’s essence is the right to exclude.

Without question, the notion of exclusion captures an important aspect of most property entitlements: namely, the privileged relationship that one person has (or sometimes a group of people have) to a resource, as compared to other non-property-holders. It is not only the case that the property-holder can prohibit others from engaging with the owned resource, but also that the property-holder is themselves entitled to engage with that resource without requiring the say-so of any other person. The idea of one person excluding others helpfully captures this one-rule-for-me/one-rule-for-everyone-else feature of property entitlements.

Even so, it is important to clarify what is meant by the ‘right to exclude’. In the context of property theory, ‘exclude’ is ambiguous. In the literature it is possible to find the idea of exclusion being applied willy-nilly to very different entities—to resources, activities, values, interests and even to the property right itself (Merrill 1998). Predictably, the term shifts somewhat in meaning in each of these different applications, at times meaning little more than ‘prohibit’, while at others meaning protection from harm, or protection from interference, or protection from trespass or loss in value. These are all distinct notions, and many of them are applicable not only to property rights, but also to many ordinary rights that are not usually spoken of in either proprietorial or exclusionary terms. (Many rights protect a person from harm, for example, but that does not make them property rights.) In shifting from one use of ‘exclude’ to another, it is possible to create a misleading impression that property-entitlements are more consistent across contexts than in fact they are.

The plainest meaning of a ‘right to exclude’, and the one adopted by most Exclusion Theorists, refers to the physical crossing by a person of a physical boundary – it refers, that is, to the idea of trespass. On this footing, it is the essence of property to have a right to exclude others from entering one’s land or possessing one’s chattels – or, to put the point more precisely and technically, it is the essence of property to have a Hohfeldian claim-right constituted by others’ duties to exclude themselves from the resource (Penner 1997). Put more simply, property implies that there is a boundary around the border of the owned entity that non-owners may not cross without the consent of the property-holder.

This does not mean non-owners cannot use or impact upon the resource if they are able to do so without actually entering or possessing it. For instance, the duty to exclude oneself from a garden does not mean that one cannot enjoy looking upon it on one’s way to work. Nor does it mean that one cannot pick up some tips for one’s own gardening endeavours from appreciation of its arrangement. In this respect Exclusion Theory’s focus on physical border-crossing parallels closely the way property-cases are often decided in law. As Lord Camden put it in the eighteenth century, ‘the eye cannot by the laws of England be guilty of a trespass’; that is, one can trespass with one’s feet or with one’s hands, but not merely by looking and listening. Equally however, the focus on border-crossing allows the possibility that a person can impact negatively on another’s property provided one does not enter onto it. For instance, Annie’s pumping out the groundwater on her property may cause Bob’s land to collapse, but Annie has not breached any duty to exclude herself from physically entering Bob’s property. The law on such questions tends to be more equivocal—in some jurisdictions it will determine that Annie’s action violated Bob’s property-right, but in other jurisdictions it will not. Even still, it is unquestionably true that harms which involve physical trespass are treated in law very differently, and usually more harshly, than harms which do not. As such, Exclusion Theory rightly directs attention to property’s allocation of specific resources to specific individuals, and the usefulness of physical encroachment as a trigger for legal action.

Several critiques may be made of Exclusion Theory. On a theoretical and normative level, some have argued that the focus on exclusion deflects attention from the way exclusion integrates with the more fundamental idea of use (Mossoff 2003). In a sense, Exclusion Theory can be thought of as a theory of non-ownership: it focuses on what property means for those who do not have it, rather than for those who do (Katz 2008). Equally though, a defender of the theory may argue that Exclusion Theory rightly places attention on the element of property that most cries out for justification—its imposition of constraining duties on everyone but the property-holder. In this respect, it is arguable that Exclusion Theory helpfully expresses a widespread and important moral norm of inviolability – the idea that some things are off-limits to people (Balgandesh 2008).

On a descriptive level, the question may be raised whether the right to exclude accurately captures the idea of property at work in applications outside the simple cases of land and chattels. This is particularly true with respect to property over intangibles, including intellectual property rights like copyright and patent, which grant entitlements over created artistic works and inventions. In such cases, Exclusion Theory’s usual reliance on the natural boundaries of the thing (the physical borders of the chattel or the land) and the notion of physical crossing apply less straightforwardly, and much controversy surrounds whether the theory manages to account for these sorts of intellectual properties. Even in application to real property, however, there are entitlements that Exclusion Theory can struggle to explain. For instance, exclusion does not seem to be a primary element of property in cases where multiple persons have overlapping properties in the one resource. Plainly, none of them can exclude each other, yet they all seem to have property.

6. Use: Harm-Based Theories

Rather than focusing on exclusion, attention may be directed at property’s capacity to protect particular uses of, and activities performed upon, a given resource. On this perspective – which might be termed Harm Theory – the essence of a property-right in some resource is not to prohibit others from trespassing across the resource’s boundaries, but instead to prohibit others from harming certain of the property-holder’s uses of the resource. These protected uses may in some cases be very specific, as occurs with fishing rights or mining rights. Or the protected uses may include a wide cluster of activities—for instance as may be gathered under the idea of protecting an owner’s quiet enjoyment of his land. The ancient property law of sic utere tuo (use your own so as to do no harm to others) may be invoked here: rather than Annie simply respecting the boundaries of Bob’s land by not crossing them, she is required to ensure that her use of her property does not harm Bob’s use of his (Freyfogle 2003). Rather than trespass, the focus shifts to notions of harm, nuisance, interference and worsening. To be sure, these concepts will often overlap with trespass, but they are not identical. There are many cases where protection of an activity from harm or interference will not require – or will require more than – rules against crossing a physical boundary.

In this respect, Harm Theory differs on practical matters from Exclusion Theory in two sets of cases. First, it will not consider boundary-crossing to be a necessary violation of the property right. The question, rather, will be whether the boundary crossing was in some sense harmful to the property-holder, given the use or set of uses to which that property holder is putting the property. If the boundary-crossing was not detrimental to the property-holder’s project, then there is ‘no-harm, no-foul’. In this first case, the duties imposed by Harm Theory are less extensive than Exclusion Theory, as some cases of boundary-crossing will not be violations of the right. Second, however, the Harm Approach will protect the earmarked uses even from the harmful actions of others who do not cross the property-boundary. As such, Annie pumping out groundwater that causes Bob’s property to collapse, or Annie building structures that block sunlight from Bob’s solar array, or Annie blocking access-ways to Bob’s property, or Annie flooding Bob’s property by damming the creek on Annie’s property, may all be violations of Bob’s property rights. In this second set of cases, the duties imposed by Harm Theory are more extensive than those created by Exclusion Theory, as they reach out to affect others operating outside the property’s borders.

Descriptively, Harm Theory can account for the many cases of apparent trespass – boundary-crossing even against the explicit will of the property-holder – that are not held to be legal violations of the property right because they were not deemed to be harmful to the property-holder’s activities (Katz 2008). In response however, the Exclusion Theorist can marshal example cases in law where trespass was prioritized over harm, and it is not easy to perceive a clear victor in this debate. However, the Harm Theorist does have one, perhaps not-so-minor, area where their account is clearly descriptively superior; this is in respect of overlapping property rights.

a. Overlapping Property: Common and Resource Property Rights

Rights to a common resource – where everyone in a given community can use the resource – come in a variety of different forms. Two are worth considering here. First, there are open access regimes, where all persons can access the resource and either: a) there are no constraints on what they may do on or with that resource, or, b) there are constraints, but these constraints allow space for people to worsen the resource in respect of the uses they and others put the resource to. Fisheries are often examples of open access regimes; everyone in the community may have the right to access and to fish in the local lake, but their unrestrained fishing ultimately impacts detrimentally on the capacity of the lake to provide fish. As Garret Hardin famously showed in The Tragedy of the Commons, in such a situation rational agents may be expected to exploit the resource to the detriment of everyone (Hardin 1968).

In at least some cases, however, communities are able to develop constraints on each person’s uses of the resource so as to ensure the resource sustains its capacity for the specified uses over long periods of time (Ostrom 1990). Sometimes these systems may be quite simple, such as the rules that determine how parks, beaches and wildlife-reserves operate, allowing all citizens access and enjoyment without destroying the resource for others. When a common resource factors in production, however, a heavier toll is taken on the resource, and more sophisticated systems are usually required to ensure its sustainability. For instance, a community may adopt a ‘wintering rule’ with respect to pasturing their cows on a commons, such that no member can pasture more cows during the summer than they can feed off their own supplies through the winter. By capping herd-numbers in this way, the commons can be protected from over-exploitation. These sort of constraints may be thought of as protecting certain uses from the harmful acts of others, and so as a species of harm-based property entitlements. One recent account of such entitlements understands common property as ‘property-protected activities’ occurring on specific tethered resources. Such property-protection includes four types of property incidents: (i) the entitlement of the property-holder to access the resource, (ii) the entitlement to use the resource for the specific activity in question (e.g. fishing, foraging), (iii) the ownership of the fruits or profits of that activity, and (iv) the claim-rights over other users that they do not worsen (harm) the resource in respect of the specific property-protected activity (Breakey 2011).

Such harm-based accounts also aim to explain the many cases of multiple property entitlements in a single resource where such overlapping entitlements are not spread across the entire community. For example, one family in a community may have foraging rights for fruit in a local common, several families may have hunting rights, and everyone in the community may have the right to gather firewood. So long as there are effective constraints on each activity ensuring that it does not harm the others, the regime is not one of open-access, but a species of property. Again, Harm Theory can make sense of these properties by focusing not on trespass over physical boundaries (as Exclusion Theory does) but rather on the ongoing protection of certain specific uses of the tethered resource.

Normatively, one of the advantages of Harm Theory is that it tightly links the concept of property to some of the more popular ethical justifications for property rights. For instance, if property is intended to be justified because it allows people to do things—to perform ongoing productive or preserving projects over time, and to more generally reap the consequences of their actions, then one might think that the primary focus should be on protecting those projects from harm. As such, protecting people’s labour (with John Locke) or their expectations about the fruits of their labour (with Jeremy Bentham) brings harm, and not exclusion, to the foreground.

Inevitably however, Harm Theory invites its own particular critiques. First, the legal protection of some uses and not others makes Harm Theories of property explicitly political in a way that Exclusion Theory for the most part avoids. On the Harm Theory, property is not neutral among the different acts property-holders might want to perform, but necessarily selects amongst them. Exclusion Theory, on the other hand, merely sets up boundaries and lets owners decide what to do within them. Second, this privileging of use threatens to derail the idea (and enormous practical utility, in terms of information costs) of property as an integrated concept consistent across contexts; a ‘bundle of uses’ may be little improvement on a ‘bundle of entitlements’ (Merrill and Smith 2001). Third, and perhaps most seriously, the fixed and specific uses (or sets of uses) that property-holders are entitled to engage in seems to depart from a very basic and intuitive thought about private property, which is that it is for the owner to decide what will happen on their property, and that their choices on this matter are to some extent genuinely open-ended. Harm Theory delimits which acts will be property-protected, and so constrains – in some cases very considerably – a property-holder’s capacity to determine what will happen on the property. As such, it may be that Harm Theory can only augment, but cannot hope to replace, rival theories of property like Exclusion Theory.

Ultimately it may be that property should be best understood as a mix of the Exclusion and Harm Theories, whereby both trespass and harm should be factored into our larger concept of property. One obvious reason for adopting this sort of mixed theory is that protecting against trespass often will be the most effective way of protecting against harm; it is far easier to detect trespassers than harmers (Ellickson 1993). This mixed view is also reflected in much legal case-law, where notions of trespass and boundary (from Exclusion Theory) interweave amongst notions of nuisance, quiet enjoyment and do-no-harm (from Harm Theory). If this combination of the two theories is correct, however, this would be an important conceptual result, because it introduces a tension into the very heart of property (Singer 2000; Freyfogle 2003). It means that in at least some cases we cannot know a priori (that is, simply from application of the concept of property) whether a property-holder or a non-property holder is entitled to perform a particular act until we settle the question of what uses are being protected from harm, what happens when two protected uses clash, and whether harm will trump trespass in this particular case.

7. Power-Based Theories: The Question of Alienation

The two theories just covered – Exclusion and Harm – share a common focus on what are called ‘first-order Hohfeldian jural relations’ (see §2 above). In particular, their dispute surrounds which types of claim-rights are held by property-owners, where the choice is between claim-rights prohibiting others from trespassing, or claim-rights prohibiting others from harming. But it is arguable that this dispute misplaces altogether the unique nature of property in terms of its second-order Hohfeldian jural relations, especially ‘powers’ (the capacity to alter others’ claim-rights with respect to the owned resource).

It has long been held by political philosophers of very different stripes that it is the quintessential mark of property that it can be traded in a marketplace. Courts of law have made similar judgments, recognizing an entitlement as property once it is established that the entitlement is tradable. Such rights of trade – as well as associated powers of waiver, management and abandonment – are second-order Hohfeldian powers, allowing an owner to alter the normative standing of others with respect to the resource. On the Power Theory, as it might be termed, to know whether a particular right is property, the decisive question to ask is whether it can be traded for money; Annie’s property essentially involves Annie having the power to altogether transfer (alienate) her rights over the resource to Bob, so that Bob becomes the property-holder, and Annie loses her property-rights with respect to that resource. Moreover, Annie can perform this alienation on condition of a like alienation by Bob, such that they trade property, or exchange property for money. On this view, an item of property is necessarily tradable, and so necessarily a commodity. As such, if a society has property rights then it necessarily has to some extent a market economy (at least with respect to those objects over which property is held).

While many theorists and laypeople view the relationship between property and commodity as simply intuitive, others mount arguments aiming to tie the two together theoretically. For instance, it may be argued that accounts of property need to pay heed to the fact that Bob’s duties with respect to Annie’s property are owed to Annie and not to society at large, and that allowing Annie to alienate those duties as she sees fit is a necessary implication of the fact that the duties are owed to her (Dorfman 2010). This line of thought on property rights may be bolstered by appeal to the ‘will/choice theory of rights,’ which holds that it is of the essence of rights more generally to be waivable and transferable (Steiner 1994). If the power to make choices over the duties others owe to us is an essential feature of rights in general, then it is plausible to think that it will also be a feature of property rights more particularly.

Against this proposed assimilation of property with commodity, however, many property theorists have argued that the essence of property need not include full powers of alienation and that there are attractive, integrated concepts of property without this element. Examples of property concepts explicitly avoiding alienation include the idea of personal property—familiar from both socialist theory and practice. Personal property may be characterized as property that cannot be sold, but which can be licensed out (Radin 1982). Other subtle variations are possible, allowing some forms of alienation and waiver, but not others. For instance, it has been argued that the concept of property necessarily allows for bequeathal and gift but does not necessarily include the power of sale. On this view, a property-holder can always give away her property or leave it to her children; to sell the property, however, requires the additional concept of contract (Penner 1997). Another variation holds that the concept of property includes the capacity for certain types of trade, but not the entitlement to receive income from managing the property (Christman 1991). A further variation again – one common in both law and custom – is the ‘classic usufruct’, where the property is held until the death of the property-holder, but cannot be transferred during their lifetime (Ellickson 1993).

One challenge arising for such accounts is that it is hard to draw a conceptual line in the sand between the types of Hohfeldian powers a property-holder does and does not have. Almost everyone will agree, for instance, that property-rights include the power of waiver – that is, that Annie is able to consent to Bob entering her land by waiving Bob’s duties of non-trespass. But it can be difficult to see how Annie can have a power of waiver without thereby having the power to manage; the capacity to consent to another person’s entry onto the property under stipulated conditions effectively allows the property-holder to manage what happens on the property. But from there, it is difficult to see how Annie can have the power of management without also having rights to income, as she can make one of the stipulated conditions for Bob’s entry onto the property that she receives some of what Bob produces. Similarly, it can be difficult to draw a strong distinction between Annie being able to give away her property at her discretion, and her being able to transfer it for money.

To be sure, this difficulty in specifying exactly which Hohfeldian powers of transfer are essential incidents of property is not impossible to overcome—and certainly neither law nor custom has any problem allowing some powers of transfer and prohibiting others (Ellickson 1993). But the existence of the difficulty does suggest that all these powers sit on a continuum, and that when crafting an integrated, coherent property-concept, the absence of a clear distinction between these powers at any given point has led different theorists to draw the line in quite different – and sometimes enormously subtle – places. Perhaps all this difficulty implies is that when seeking integrated property concepts, the conceptual linkages between Honoré’s incidents and between Hohfeld’s jural relations mean that such categories should not be relied upon to provide the desired boundaries. With this in mind, §10 below describes two theories of property that cut across the dimensions described by Honoré’s and Hohfeld’s systems. Alternatively, another response is to make property’s powers a continuum concept. An example of this idea is J. W. Harris’ theory of property (Harris 1996). For Harris, property has two necessary elements: trespassory rules (familiar from the Exclusion Theory described above in §5) and the ownership spectrum. The ownership spectrum is a continuum ranging from personal use-privileges to control-powers allowing management and – at the very top of the spectrum – full alienation. Harris is then able to specify distinct types of property – half property, mere-property, and full-blooded ownership – as residing at distinct points on this ownership spectrum.

8. Immunity-Based Theories

An additional type of second-order Hohfelidan jural relation is implicated in property. Rather than focusing concern on how Annie can alter others’ duties with respect to the property (the question of powers), attention may be turned to the manner in which Annie is protected from having her standing with respect to the property altered by others (the question of immunity).

Some degree of immunity is an essential element of property. If Annie has an entitlement to a resource that can be dissolved merely by Bob’s say-so, then it seems fair to say that Annie does not have property in that resource, but only some lesser entitlement. More specifically, if Annie holds property over Blackacre, then her neighbor Bob cannot, without Annie’s consent, transfer the ownership of Blackacre to himself; Bob cannot expropriate Blackacre. As such, some degree of immunity from the non-consensual dissolution of a property-holder’s entitlements over her owned resource appears to be a necessary condition of property.

Interestingly, the seventeenth century political philosopher John Locke took seriously the possibility that an immunity from expropriation was a sufficient condition for property. He thought that any entitlement that could not be removed by others counted as property, defining property as ‘that without a man’s own consent it cannot be taken from him.’ Such a position accounts for the very wide concept of property that Locke used at various points throughout his famous Two Treatises on Government. Since many ordinary rights (such as to free speech and bodily security) are immunized from others’ dissolution, advancing such an immunity as a sufficient condition of property means that property encompasses all natural or human rights. This perhaps seems to a modern eye to explode rather than inform the concept of property.

Even making an immunity from expropriation only a necessary condition of property is controversial however, as it seems to imply that much (perhaps all) takings or taxation by the government necessarily impinges on property. Clearly, there are significant consequences at stake here for distributive justice, as taxation in market economies is the primary source of funds for state welfare, education and healthcare. For this reason, various attempts have been made to define integrated property concepts so as to leave space for taxation. For instance, one approach grants immunity against expropriation so long as the property-holder is engaging purely with their own property, but weakens that immunity when the property-holder starts to derive market income through management or sale of the property (Christman 1991). Such an approach ties the question of immunity to the question of transfer and alienation discussed in the previous section (§7). Against such attempts, it has been argued that all concepts of property allowing the possibility of non-consensual expropriation necessarily have a strained sense about them, as they artificially try to make the concept of property compatible with its own extinction (Attas 2007). On this view, while various regulations of property may be consistent with the idea of property, expropriation itself cannot be a part of the concept. If we are committed to taxation, it is argued, property’s essential tie to immunity from expropriation means we must entirely forgo property as an organizing idea for our economic and political systems.

9. Remedy-Based Theories

Previous sections have located the essence of property in first-order Hohfeldian claim-rights (claim-rights prohibiting exclusion and harm) and second-order Hohfeldian jural relations (powers of transfer and immunity from expropriation). But there is one further dimension on which property may be characterized: remedies—the question of what is done when the rules of property are broken.

An influential theory developed by legal scholars Calabresi and Melamed distinguishes property-rules from liability-rules and inalienability-rules (Calabresi and Melamed 1972). Property-rules are those entitlements that may only be removed with the consent of the rights-holder; the rights-holder gets to name the conditions under which they consent to extinguish the entitlements that would otherwise apply. Liability-rules, on the other hand, allow entitlements to be removed by a party so long as that party pays a specific cost. This cost is objectively determined by the state, and not by the subjective choice of the entitlement-holder. Inalienability-rules prevent entitlements being removed or transferred at all; if an entitlement is inalienable then even the right-holder herself cannot waive or alienate the entitlement. Different rules can apply to the same resource in different contexts. For instance, a person’s home is usually protected by property-rules with respect to other citizens (who, if they want to buy, must meet the owner’s asking price) but is only protected by liability-rules with respect to the state (as the state can use its powers of eminent domain to remove the entitlements in return for an objectively determined payment to the homeowner). Calabresi and Melamed’s distinction has relevance to the issues of immunities and powers discussed in the last two sections (§7-8). With respect to powers it implies that entitlements protected by inalienability-rules are not property, and thus that property implies alienability; and that entitlements protected only by a liability-rule are not property. With respect to immunities, the use of property-rules rather than liability-rules implies that property includes an immunity from forced transfer (by ordinary citizens, at least) through payment of an objectively determined sum.

Additionally though, Calabresi and Melamed’s analysis applies to remedies: the question of what happens when the initial rules (whatever they are) are broken. Imagine Bob illicitly breaches Annie’s property rights in X by taking X. However, upon being caught Bob gets to keep X, and only has to pay Annie a (non-punitive) objectively determined estimation of the cost of X. While the letter of the law may say that Bob has a duty to exclude himself from taking Annie’s property, in reality Bob can take what he wants from Annie and then simply pay the cost for that item as determined by the state. In such a case it may be doubted whether Annie really has a property right at all. Similarly, if Bob is found to be engaged in an ongoing breach of Annie’s property rights, it may seem obvious that a court will order Bob to stop his ongoing violation (this is called ordering an injunction or injunctive relief), rather than merely imposing an objectively-determined cost of damages upon Bob and letting him continue the violation. But appearances can be deceiving. If Bob accidentally built his house on some of Annie’s land, the court may award damages to Annie but not force Bob to remove his transgressing building—and there are other cases where property-violations are not automatically granted injunctive relief (Balgandesh 2008). Ultimately, then, while there is clearly some conceptual relationship between property rights and the types of remedies that are to be applied if and when those rights are violated, precisely what that relationship amounts to is controversial. Perhaps the most that can be said with confidence is that property remedies, reflective of the fact that property’s duties are owed to the property-holder, must be a part of private law as well as public law, and so must in principle allow owners to seek damages over violations of their property rights, as well as allowing the state to perform criminal sanctions on the person who violated those rights (Dorfman 2010).

10. Examples of Cross-Cutting Theories

The foregoing five sections have described theories focusing in turn on one particular dimension of property: claim-rights, powers, immunities or remedies. It may be, however, that the best theory of property will be one that cuts across these dimensions and carries implications for all of them. Two examples of such cross-cutting theories follow.

a. Radin and Property for Personhood

In her influential 1982 article Property and Personhood Margaret Radin does not aim to provide a general theory of property, but seeks instead to explore one specific type of property relationship: the personality theory of property. This theory describes the specific cases where property comes to be, in a deep philosophical sense, a part of the person who owns it. Arising through the significance of things in constituting our memories, our actions, our individuality and our continuing plans and expectations, this type of deep attachment between person and thing (consider wedding rings and other items with sentimental value) gives rise to a theory of property-for-personhood with implications for each of the dimensions listed above.

In terms of claim-rights, the inviolability and sanctity of property-for-personhood implies the centrality of rights of exclusion from the object itself. It is important that nameless others do not access and use the personal object, rather than merely prohibiting their harming it in some fashion. Turning to powers, as part of the owner’s person, personal property is not a commodity; it is precisely the definition of personal property that it is not freely exchangeable for functional equivalents or for its market price. While this does not automatically mean alienation should be legally prohibited for such items (an object can shift over time from one category to another, so implementing such a rule would be difficult), it is at least clear that powers of alienation are not an essential part of the entitlements of property-for-personhood. In terms of immunities and remedies, property-for-personhood warrants the stronger protection of Calabresi and Melamed’s property-rule rather than the lesser protection afforded by a mere liability-rule. Other citizens – and perhaps even the state – should not be able to expropriate parts of a property-holder’s very person. Reflective of this, courts would be expected to utilize injunctive relief (that is, they would order the defendant cease the violating behaviour) as remedies in the case of a continuing violation of property-for-personhood, rather than merely awarding damages. In this way, the implications of a specific concept of property can be traced as they cut across the several dimensions described above.

b. Katz and Ownership as Agenda-Setting

Recently, Larissa Katz has advanced an agenda-setting theory of property in land, whereby the property-owner has the supreme power to set the agenda for the property (Katz 2008). This theory can be viewed as a sophisticated combination of a Harm Theory and a Power Theory. The theory says that a property owner can exclusively choose what particular type of act they will perform on the property – for instance, they may adopt residential, agricultural, or various sorts of industrial uses of their land. This is no mere liberty of action however—with the performance of these different activities, the owner sets the agenda for the property, shaping the duties of others with respect to that property. Non-owners have different clusters of duties imposed upon them depending upon the activity that has been undertaken by the owner; they must accord their behaviour, vis-à-vis the resource, with the agenda that has been set. As such, the agenda-setting capacity is a Hohfeldian power that alters the duties of non-owners with respect to the resource. Once the agenda is set through the owner’s chosen activities, the ensuing entitlements are thereafter modeled by the Harm Theory; others may be allowed to cross the boundaries of the property in a variety of contexts, but in doing so they must ensure their actions do not impact upon the specific activity that the owner is performing. The agenda, but not the thing, shapes the duties of others, and harm, but not exclusion, is prioritized.

11. Socialist and Egalitarian Property

Much of the foregoing has considered different theories of private property—with the exception being the universal endowments of common property discussed in §6.1. But it may be enquired what sort of property concepts arise from socialist theory and practice. Naturally, there are many different answers to this question, particularly if its scope is expanded to include, say, contemporary theories of market socialism (which aim to assimilate socialist theories of justice with elements of market-based economies), the types of property relationships that were expected to emerge during the transition from capitalism to socialism, and the various types of property existing in law and de facto in particular socialist regimes throughout recent history. In the main, however, two answers predominate.

At least since the beginning of the twentieth century, socialism has been identified with the public ownership of the means of production. This directly implies the collective ownership of those assets playing a role in production. Equally though, it leaves room for each person to hold property – even private property – in particular resources, provided these entitlements do not allow for private production to occur. With this restriction in mind, concepts of private property available for use in socialist regimes will exclude market transfers, with the intention of facilitating the elements of property that allow personal use, and prohibiting those that allow control over other persons. Individual citizens thus will be entitled to personal property (§7) and to property-for-personhood as Radin defined that term (§10.1), and they may also have common property in certain public amenities.

As well as the non-productive property entitlements of individual persons, the defining feature of a socialist economy is that productive resources are collectively owned. There are three features of such ownership. First, the group as a whole, or some subset understood to be representative of that whole, determines the use to which a resource will be put and manages the resource. Second, decisions on how the resource will be used are made through reference to the collective interest; the property is to be managed in order to produce what the collective requires. Third, the property’s management must also instantiate the proper empowerment of those citizens who labour upon it; workers must not be alienated from their labour even for the sake of public benefit elsewhere.

Naturally, this general characterization may be filled out in very different ways, depending upon who represents the collective, how centralized their decision-making is, how the collective’s interests are defined, what counts as proper empowerment, how the relationship between collective and personal property is managed, and so on (Kulikov 1988). Cooperative property and to an extent some of the property systems of communes may be understood as collective property writ on a smaller scale—being held by small communities and working groups rather than entire nation-states. More decentralized socialist regimes have made extensive use of this form of productive arrangement.

There is one further property-concept worth noting here: joint ownership. A resource is jointly-owned when each member of a community has a veto-right over what may be done or produced on the resource; no production is allowed without the prior agreement of every member. This concept of property is rarely found in law or custom. Its most common use is as a theoretical device for modeling an initial normative relation between people and land (Cohen 1995). In this way joint ownership sets down an imagined initial situation where no productive action can occur without the agreement of every joint owner. This standpoint then serves as a conceptual point of departure from which further contracting can occur. There are good reasons for thinking that the property-entitlements arising from such contracting will be highly egalitarian, as the veto-power joint ownership gives each member of the society will allow them to bargain for a share of whatever is produced.

12. References and Further Reading

Bundle Theory and the Disintegration of Property

- Hohfeld, W. “Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning.” Yale Law Journal 23 (1913): 16-59; (Contined in YLJ 26, 1917: 710-69.)

- Landmark pair of articles analysing rights (including property rights) into constituent parts.

- Cohen, Felix. “Transcendental Nonsense and the Functional Approach.” Columbia Law Review 35.6 (1935): 809-49.

- Advocates a scientific and functional approach to law; argues the concept of property (among others) to be an unwanted supernatural entity.

- Grey, Thomas. “The Disintegration of Property.” Property: Nomos XXII. Eds. Pennock, J. Roland and J. W. Chapman. New York: New York University Press, 1980. 69-86.

- Influential argument against integrated concepts of property.

- Merrill, Thomas, and Henry Smith. “What Happened to Property in Law and Economics?” Yale Law Journal 111 (2001): 357-98.

- Illustrates why Coase-inspired property theorists gravitated toward the Bundle (and also use/harm) approach; argues this approach obscures crucial features of property.

Full Liberal Ownership

- Honoré, A. “Ownership.” Oxford Essays in Jurisprudence. Ed. Guest, A. London: Oxford University Press, 1961. 107-47.

- Seminal article listing eleven incidents of Full Liberal Ownership (often used as a comprehensive list of the potential sticks in property’s bundle).

- Epstein, Richard. Takings: Private Property and the Power of Eminent Domain. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Influential libertarian reading of the US Takings Clause through the Hohfeldian lens; argues the dissolution of any incident of property is a taking of property.

Integrated Theory

- Mossoff, Adam. “What Is Property?” Arizona Law Review 45 (2003): 371-443.

- Sustained argument for Integrated Theory, including its historical pedigree from the early modern period in Grotius and Locke.

Exclusion Theories

- Balgandesh, Shyamkrishna. “Demystifying the Right to Exclude: Of Property, Inviolability and Automatic Injunctions.” Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 31 (2008): 593-661.

- Argues that property is based on a principle of inviolability, and so constituted by claim-rights that others exclude themselves. Argues against remedy-based property theories like Calabresi and Melamed’s.

- Merrill, Thomas. “Property and the Right to Exclude.” Nebraska Law Review 77 (1998): 730-55.

- Argues the essence of property is the right to exclude, from which the other aspects of property can be derived.

- Penner, J. The Idea of Property in Law. Oxford: Clarendon, 1997.

- Classic statement of exclusion theory; property includes powers of abandonment and gift, but not alienation, which requires the addition of the concept of contract in law.

Harm-Based Theories, including Common Property

- Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Influential study of common property, describing its diversity, nature, history and variable capacity to resist tragedy.

- Breakey, Hugh. “Two Concepts of Property: Ownership of Things and Property in Activities.” The Philosophical Forum 42.3 (2011): 239-65.

- Argues that a (Harm-based) concept of property-protected activities solves problem cases (common property, resource property, property in labour, etc.) encountered by Exclusion Theory.

- Hardin, Garrett. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science 162 (1968): 1243-48.

- Landmark article describing how rational actors degrade common (read open-access) resources.

Environmental and Community-Based Conceptions of Property

- Freyfogle, Eric. The Land We Share. London: Shearwater Books, 2003.

- Describes the fluidty and diversity of property-entitlements through US history, and their responsiveness to community and ecological needs; emphasizes internal tensions within property entitlements.

- Singer, Joseph. Entitlement. London: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Argues control over a property should be delineated by individuals’ protected interests in that property, rather than by abstract notions of ownership; marshals an array of tensions within ownership.

Power-Based Theory

- Dorfman, Avihay. “Private Ownership.” Legal Theory 16 (2010): 1-35.

- Identifies property with the capacity to alter others’ normative standing with respect to the resource. Links this feature with property’s status in private law.

- Christman, John. “Self-Ownership, Equality, and the Structure of Property Rights.” Political Theory 19.1 (1991): 28-46.

- Distinguishes property’s ‘use’ rights (including alienation) from its ‘control’ rights (especially income), and argues for the ethical priority of the former.

- Steiner, Hillel. An Essay on Rights. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994.

- Links Will/Choice theory of rights to property entitlements in developing a left-libertarian position.

Immunity-Based Theory

- Attas, Daniel. “Fragmenting Property.” Law and Philosophy 25.1 (2007): 119-49.

- Describes structural relations between Honore’s property-incidents; argues immunity from expropriation is a necessary incident of property.

Remedy-Based Theory

- Calabresi, G., and D. Melamed. “Property Rule, Liability Rules and Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral.” Harvard Law Review 85 (1972): 1089-1128.

- Focusing on remedies and immunities, distinguishes property-rules, inalienability-rules and liability-rules.

Cross-Cutting Theories

- Katz, Larissa. “Exclusion and Exclusivity in Property Law.” University of Toronto Law Journal 58.3 (2008): 275-315.

- ‘Agenda-setting’ theory of property: property’s duties are not set by exclusion from the resource, but rather shaped to conform with the agenda the owner has set for the resource.

- Radin, Margaret. “Property and Personhood.” Stanford Law Review 34 (1982): 957-1015.

- Definitive account of the personhood theory of property; investigates the special case where property forms part of the person of the property-holder.

Socialist Property

- Kulikov, V. V. “The Structure and Forms of Socialist Property.” Problems of Economics 31.1 (1988): 14-29.

- Details the two major forms of property applicable to socialist regimes (collective and personal property) and their inter-relation. Considers the use of personal private production in Soviet socialism.

- Cohen, Gerald. Self-Ownership, Freedom and Equality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Searching investigation of normative implications of different property regimes. Chapter 4 describes ‘Joint Ownership’.

General Literature

- Ellickson, Robert. “Property in Land.” Yale Law Journal 102 (1993): 1315-400.

- Detailed analysis of the complexities of property in land, combining historical cases and rational-actor theory, and considering private, common, and communal property-arrangements.

- Wenar, Leif. “The Concept of Property and the Takings Clause.” Columbia Law Review 97 (1997): 1923-46.

- Argues, with special reference to the US takings clause, that property should be viewed as the thing that is the object of (Hohfeldian) property rights.

- Harris, James. Property and Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Property based on twin notions of trespassory rules and the ‘ownership spectrum’, a continuum ranging from mere use-privileges through to control-powers and alienation.

- Waldron, Jeremy. “What Is Private Property?” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 5 (1985): 313-49.

- Sustained argument against property skepticism; private property is a broad concept (that resources are allocated to particular individuals, who determine their use) of which particular conceptions are possible. Considers common and collective property.

- Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. New York: Hafner, 1947 (1689).

- Perhaps the most influential treatise on property ever penned, though subject to divergent interpretations. As well as the famous Chapter Five of the Second Treatise, see First Treatise sections 39-41, 86-92 and Second Treatise sections 135-40, 159, 172-74.

- Macpherson, C. B., ed. Property: Mainstream and Critical Positions. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1978.

- Useful anthology of major property theorists throughout history, and more recent critical arguments.

Author Information

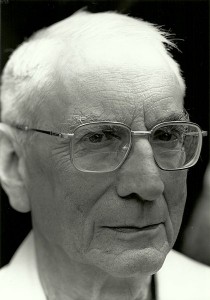

Hugh Breakey

Email: h.breakey@griffith.edu.au

Griffith University

Australia

Donald Davidson (1917-2003) was one of the most influential analytic philosophers of language during the second half of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first century. An attraction of Davidson’s philosophy of language is the set of conceptual connections he draws between traditional questions about language and issues that arise in other fields of philosophy, including especially the philosophy of mind, action theory, epistemology, and metaphysics. This article addresses only his work on the

Donald Davidson (1917-2003) was one of the most influential analytic philosophers of language during the second half of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first century. An attraction of Davidson’s philosophy of language is the set of conceptual connections he draws between traditional questions about language and issues that arise in other fields of philosophy, including especially the philosophy of mind, action theory, epistemology, and metaphysics. This article addresses only his work on the