Constructivism in Metaethics

It is difficult to provide an uncontroversial statement of constructivism in metaethics, since the terms of this doctrine are themselves the focus of philosophical debate. However, this view is now perhaps most commonly understood as a metaphysical thesis concerning how we are to understand the nature of normative facts–that is, facts about what we ought to do. Most broadly, it is the view that the correctness of our judgments about what we ought to do is determined by facts about what we believe, or desire, or choose and not, as realism would have it, by facts about a prior and independent normative reality.

Defenders of constructivism have claimed that it represents a new, free-standing alternative to familiar approaches in metaethics. If they are correct, traditional discussions in metaethics have overlooked an important position, one that is supposed to adequately explain the nature of our ethical thinking and practice while avoiding the kinds of objections that traditional views struggle with. However, in order for this to be the case, constructivism must be characterized more narrowly—as the broad characterization above would appear to be true of a number of well-established positions in metaethics (including response-dependence theories and other forms of subjectivism). What form this narrower characterization should take and whether constructivists can make good on this more ambitious claim remains controversial.

This article starts out in section 1 with a brief account of the origins of contemporary discussions of constructivism. Sections 2 and 3 canvass the main motivations and arguments for constructivism along with the various ways in which the view has been interpreted. Section 4 introduces a serious challenge to the ambitious claim that constructivism represents a new, free-standing approach in metaethics. Section 5 entertains a proposal developed in the 21st century that this challenge might overlook.

Table of Contents

- Origins of the View

- The Scope and Ambition of Metaethical Constructivism

- Motivation and General Argumentative Strategy

- Is Constructivism “Free-Standing”?

- A Challenge to Traditional Metaethics

- References and Further Reading

1. Origins of the View

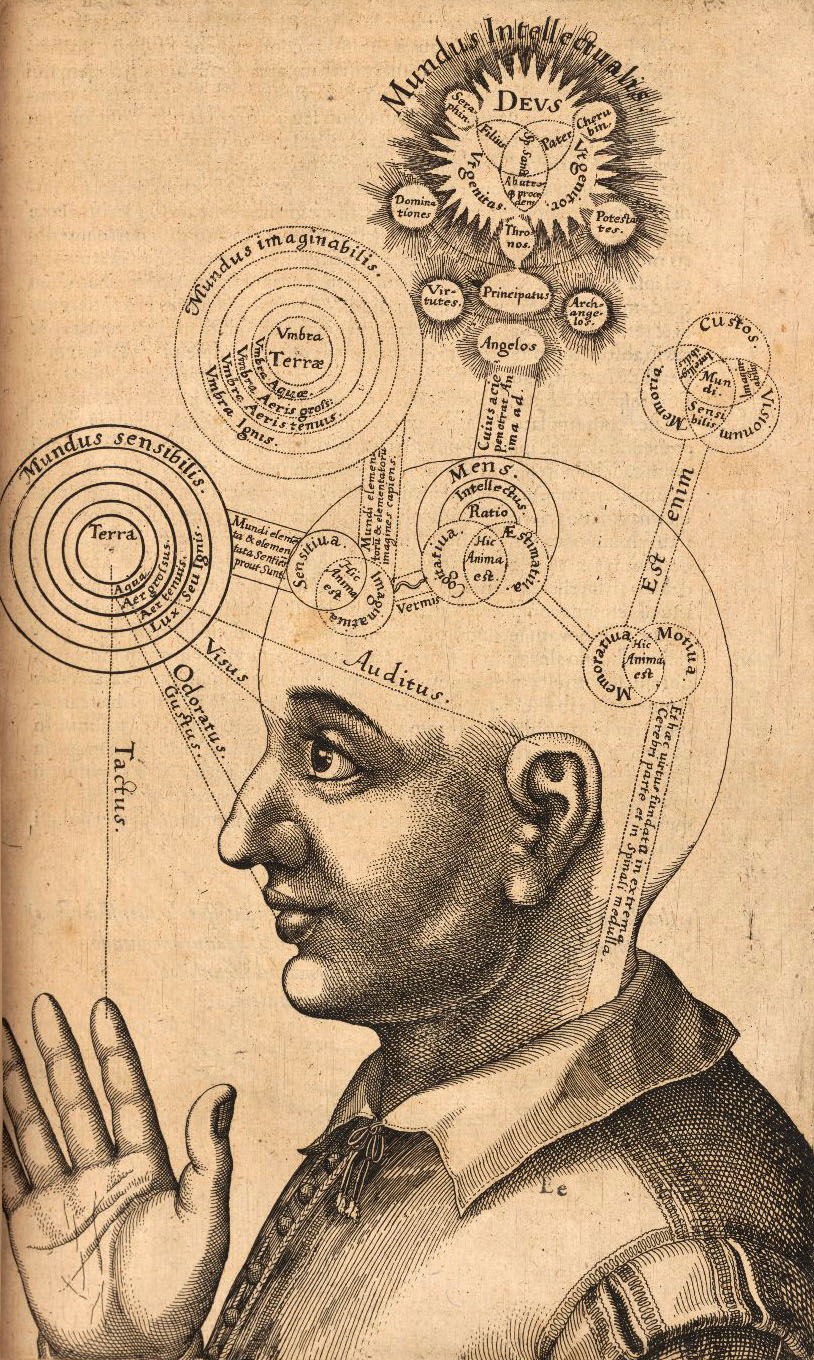

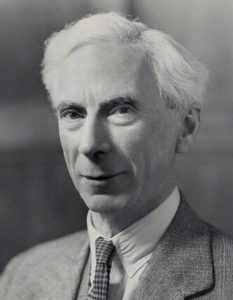

Contemporary discussion of constructivism in ethics largely originates in the work of John Rawls. Along the way to developing a normative foundation for just political institutions that could be divorced from deep and irreconcilable metaphysical disagreements, Rawls entertained a view that he called Kantian constructivism.

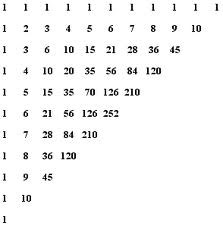

Kantian constructivism holds that moral objectivity is to be understood in terms of a suitably constructed social point of view that all can accept. Apart from the procedure of constructing the principles of justice, there are no moral facts. Whether certain facts are to be recognized as reasons of right and justice, or how much they are to count, can be ascertained only from within the constructivist procedure, that is, from the undertakings of rational agents of construction when suitably represented as free and equal moral persons. (1980: 519)

The parties in the original position do not agree on what the moral facts are, as if there already were such facts. It is not that, being situated impartially, they have a clear and undistorted view of a prior and independent moral order. Rather (for constructivism), there is no such order, and therefore no such facts apart from the procedure of construction as a whole; the facts are identified by the principles that result. (1980: 568)

According to the view Rawls presents here, it is not the case that the moral facts merely coincide with such agreements or that the choice procedure may be used to discover what the relevant standards are. Rather, according to constructivism, moral truths (for example, truths about “right and justice”) are determined by procedures in the sense that the moral standards that fix the relevant class of moral facts are constituted by their emergence from special procedures. It is these facts that make our moral assertions true or false. This is what Rawls means when he says that there are no moral facts apart from the procedure.

Rawls discusses Kantian constructivism across a number of different works. However, his most thorough treatment of the view can be found in the above-quoted Dewey Lectures, collectively titled “Kantian Constructivism in Moral Theory”. Here, like in many of his other works, Rawls is primarily concerned with describing and defending an interpretation of justice as fairness–“the idea that the principles of justice are agreed to in an initial situation that is fair” (1971/1999: 11). Rawls famously argues that facts about justice are fixed by principles that would be agreed to in the original position, a procedure in which free and equal citizens agree to terms of social cooperation under the condition that they do not know facts about who they are or what they deeply care about (what Rawls refers to as “the veil of ignorance”).

Some scholars, including Rawls, see a historical precedent for metaethical constructivism in the work of Immanuel Kant. This is why Rawls and some other metaethical constructivists have described their views as Kantian. However, as a point of historical interpretation this is controversial. More recently, philosophers have developed versions of constructivism that are supposed to find their inspiration in the work of other historical figures. For example, along with the Kantian varieties, one can now find Aristotelian (Lebar 2008), Humean (Street 2008, 2010; Lenman 2010), and Nietzschean (Silk 2014) versions of constructivism represented in the philosophical literature.

Although Rawls is generally credited with introducing constructivism into contemporary metaethical debates, the details of his own presentation have tended to obscure the underlying view. In particular, his focus on the facts of justice, as opposed to moral or normative facts more generally, has led many to interpret him as merely presenting a restricted form of constructivism, one that is compatible with a number of metaethical interpretations (including realism). Moreover, Rawls is clear in later works that political constructivism (the name for his mature interpretation of justice as fairness) is intended as a practical doctrine, not a metaphysical one; it should be interpreted as neutral with respect to deeper philosophical commitments that could potentially be the source of reasonable political disagreements. This has led those interested in the view to look elsewhere for a full-fledged metaethical account of constructivism.

2. The Scope and Ambition of Metaethical Constructivism

As the preceding discussion of Rawls already suggests, there are different ways of interpreting constructivism depending on how one characterizes the scope of the view. And how one characterizes the scope depends in turn on how metaethically ambitious one intends one’s constructivism to be. The following subsection will present Plato’s famous Euthyphro Question as a way of introducing what is perhaps the broadest way of capturing constructivism. Although this broad characterization captures something that is recognizably metaethical, it also ends up capturing too much and, consequently, fails to describe constructivism in a way that would make it a novel and interesting alternative to familiar metaethical positions. The three remaining subsections present narrower conceptions of the view and discuss some of the challenges that defenders of these forms of constructivism face.

As we will see, these narrower versions of constructivism can be distinguished along one of three separate axes. The first axis concerns whether constructivism counts as a first-order account of some particular domain of ethical thinking or a second-order (that is, metaethical) account of the nature of ethical thinking as such. The second axis concerns whether we should expect constructivism to yield convergence on a single class of correct ethical judgments. The third axis concerns whether a constructivist account of the nature of ethical thinking as such counts as a novel, free-standing metaethical interpretation or, rather, as a version of one or another familiar alternatives. Each of these axes will be explored in turn.

a. The Euthyphro Question

Ethical practice includes certain characteristic activities: we value things; we take actions to be wrong, or right, or permissible; we also take some things to count as reasons for acting. One question that metaethics considers is the relation between these activities and the kinds of properties and facts we most generally refer to when using evaluative, moral, and normative language (if indeed we use it to express a state of mind that refers to anything at all).

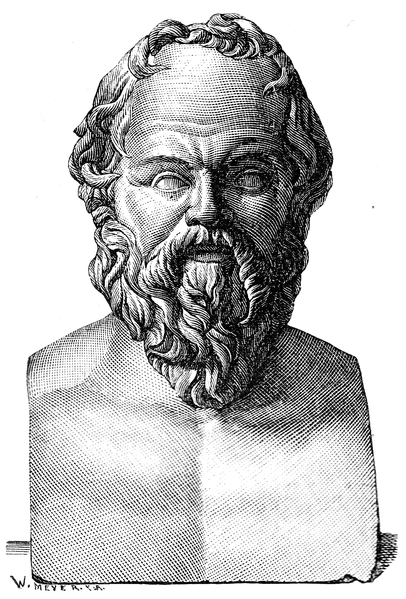

Although contemporary philosophy has generated a flurry of literature on this topic, the underlying question is a very old one. It is arguably a version of the one that Plato entertains in his presentation of a dialogue between Socrates and his eponymous interlocutor, Euthyphro. There the topic is piety. Specifically, is something pious because the gods love it? Or do the gods love it because it is pious? Plato’s brief arguments in the dialogue have been interpreted in different ways and done little to quiet interest in these questions. In order to broaden the terms of the discussion, we may recast Euthyphro’s question “in rough secular paraphrase” (Street 2010: 370).

- Do we value things because they are valuable? Or do things have value because we value them?

- Do we take certain actions to be wrong (or right or permissible) because they are wrong (or right or permissible)? Or are these actions wrong (or right or permissible) because we take them to be so?

- Do we take certain features of the world to count as reasons for action because they are reasons? Or do these features count as reasons for action because we take them to be so?

These are metaphysical questions. How we answer them will say something about the kinds of facts or properties that exist and what they are like–for example, whether an account of these facts and properties must make essential reference to these activities or the standpoints that characterize them. Constructivists–about (i) value, or (ii) morality, or (iii) reasons–answer “no” to the first of each of these pairs of questions and “yes” to the second. Realists–about (i) value, or (ii) morality, or (iii) reasons–answer “yes” to the first of each of these pairs of question and “no” to the second. In order to simplify things, this article will use “ethical” to refer to the broadest category of practical thinking, one encompassing all three of the categories above. In other words, then, the distinction the Euthyphro question prompts us to consider is one between constructivism and realism in metaethics.

Things are actually more complicated here. Neither constructivism nor realism may be alone in taking these particular positions, depending on how one defines each view. On the one hand, one might object that the distinction is not merely between constructivists and realists but between constructivists and realists or quasi-realists. Defenders of quasi-realism, such as Simon Blackburn, explicitly claim that they side with realists on this issue but, nevertheless, reject the realist’s view about what it is to make an ethical judgment–that is, they reject the realist’s account of the semantics of ethical terms and expressions and its accompanying metaphysical commitments. On the other hand, one may object that a defender of a response-dependence theory or subjectivism, more generally, would respond to these questions in the same way that the constructivist does. Although the Euthyphro question is a helpful point of entry for understanding what is generally at issue in debates between constructivists and realists, the distinction it introduces captures broader families of views under which constructivism and realism fall. Hence, if we are to understand what is special and interesting about constructivism and the challenge it poses to realism, we must introduce a further set of distinctions.

b. Local versus Global

One such further distinction concerns whether we ought to understand constructivism as restricted to a local domain of ethical discourse or whether we ought to take constructivism to provide a global account of the nature of ethics (Enoch 2009). For reasons that will become clear in the course of the discussion, this distinction is also sometimes described in terms of “restricted” versus “thoroughgoing” accounts of constructivism (see Street 2008 for coinage of these terms). According to the former understanding, one could opt to provide a constructivist account of a species of ethical facts–for example, facts about justice–but remain silent as to whether other species of ethical facts–for example, facts about morality or reasons for action–are constructed. According to the latter understanding, constructivism provides the correct account of all ethical facts (including facts about justice, morality, value, and reasons). This distinction matters for two reasons.

First, many early and influential presentations of constructivism in ethics appear to be restricted to local domains of ethical discourse. For example, let us consider Rawls’s justice as fairness and T.M. Scanlon’s (1998) constructivist view of morality, or what we owe to each other. According to the former, the facts of justice are determined by principles agreed to by free and equal citizens who are faced with the task of establishing fair terms of social co-operation. According the latter, the facts about which acts are morally wrong are determined by whether these acts “…would be disallowed by any set of principles for the general regulation of behaviour that no one could reasonably reject as a basis for informed, unforced, general agreement” (Scanlon 1998: 153). These two views count as forms of constructivism insofar as each characterizes a particular class of ethical facts (facts about justice, facts about morality) as a function of our volitional attitudes–that is, facts about what we would will, or choose, or agree to, or reject.

As we have already seen, Rawls would appear to restrict his constructivist treatment to facts about justice. In fact, his mature statement of political constructivism would appear to require this. Rawls argues that a constructivist account of all of morality (or value or reasons for action) would be subject to reasonable disagreement and could not serve as a stable basis for an enduring consensus about what justice requires. Similarly, Scanlon restricts his constructivist account of morality to facts about what is right, wrong, and permissible; it does not extend to all facts about what our reasons for action are.

Second, such local forms of constructivism would appear to be compatible with different metaethical interpretations (including realism) and, hence, would not count as competitors to standard alternatives in metaethics. In order to illustrate this point, let us assume (as many philosophers now do) that the concept of a reason is the basic normative concept which unifies different areas of ethical thinking and practice–that is, different areas of ethical discourse are ultimately concerned with particular classes of practical reasons. Working under such an assumption, one might say that Rawls’s political constructivism grounds reasons of justice in a further set of reasons: namely, those had by free and equal citizens who are faced with the task of establishing fair terms of social co-operation. Similarly, one might say that Scanlon’s moral constructivism grounds moral reasons in further reasons: namely, a reason to live together with others on terms that they could not reasonably reject together with reasons for rejecting proposed sets of moral principles. But importantly, neither Rawls nor Scanlon provides an account of the nature of these grounding reasons. Rawls’s political constructivism does not attempt to explain what it is for free and equal citizens in this situation to have such reasons; Scanlon’s moral constructivism does not explain what it is to have a reason to live together with others on terms that they could not reasonably reject or what it is to have reason to reject a proposed set of moral principles. In principle, one might explain these grounding reasons in non-constructivist terms–for example, in terms of expressivism or even realism. Indeed, Scanlon himself appears to favor a kind of non-naturalist realist interpretation of these more basic reasons. Yet another option would be to explain these grounding reasons themselves in constructivist terms.

A global form of constructivism is one that attempts to explain the nature of reasons as such in constructivist terms. Again, we will follow defenders of this view and assume here that the concept of a reason is the basic normative concept. It follows then, on this view, that all normative facts are constructed. In order for this to be the case, however, constructivism cannot privilege any one class of substantive reasons as the grounds for all the others. For again this would leave open the possibility of explaining these grounding reasons in terms of some other metaethical interpretation. Rather, a global constructivism must be thoroughgoing and apply to all practical reasons; it must avoid making any substantive commitments about the content of our practical reasons.

In other words, constructivism must be characterized formally (Street 2010: 369). This means that what it is to have a reason is not characterized in terms of other kinds of reasons but, rather, in terms of certain formal conditions (for example, consistency and coherence) that one’s attitudes must satisfy. On this view, one has a reason to perform some act just in case the idealized set of attitudes one would have, were these formal conditions to be satisfied, would (in some sense) support performing this act. By characterizing what it is to have a reason in such terms, global (or thoroughgoing) constructivism would at least appear to be incompatible with the kind of objectivity involved in a robust understanding of ethical realism (see section 3a for discussion). However, whether this characterization suffices to distinguish global constructivism from other familiar non-realist alternatives in metaethics is less clear. Before discussing this, one should note two further distinctions that have been made within the class of global constructivist views.

c. Humean versus Kantian

Sharon Street (2010) has observed that global, formally-characterized versions of constructivism may be further divided into those views that guarantee convergence on a single class of substantive reasons for action and those that do not guarantee such convergence. In other words, global constructivists may disagree about whether the formal constraints on one’s attitudes are sufficient for generating a single set of normative truths or whether these constraints may yield different, conflicting sets of normative truths depending on the attitudes one starts out with. The former she calls Kantian constructivism (note that, unlike Rawls, Street restricts the use of this term to forms of global constructivism); the latter Humean constructivism.

According to Humean constructivists–which importantly includes Street (2008, 2010)–formal construction conditions constrain what one’s reasons are but they do not fully determine the content of the reasons that one has; rather, the content of one’s reasons depends to a significant extent on the content of the attitudes that one starts out with. So, for example, two people with radically divergent attitudes (beliefs, desires) to start with are likely going to have divergent sets of reasons for action. In other words, Humean constructivists are open to the possibility of a kind of relativism about practical reasons. This means that, on their view, it might turn out that when the constructivist’s formal conditions are applied to most people’s attitudes, they yield a set of practical reasons that support common-sense views about morality, like the view that we have reason not to torture others for fun. However, on their view, it might also turn out that an ideally-coherent Caligula–that is, someone who values torturing others for fun above all else and whose attitudes satisfy all of the formal constructivist conditions–has absolutely no reason not to torture other people for fun (Street 2009, 2010). Of course, such a view fails to conform extensionally to many people’s considered judgments about the substance of practical reasons. This is considered by some to be a serious theoretical cost to accepting this form of constructivism.

According to Kantian constructivists like Christine Korsgaard (1996), the formal conditions of construction will always generate a single class of normative outcomes, regardless of the attitudes one starts out with–that is, even if one starts out with the non-idealized attitudes of a Caligula (generally considered a sadistic and insane tyrant). In other words, Kantian constructivists think that they can preserve a strong, anti-relativist sense of objectivity for practical reasons without the controversial metaphysical commitments of realism. Moreover, Kantian constructivists argue that the single class of practical reasons generated by constructivism is also the very same class of reasons traditionally supported by “common sense”–that is, one including moral reasons to keep one’s promises, to aid, and to forebear from harming others. However, some philosophers argue that the constructivist cannot guarantee such convergence without smuggling in realist metaphysical commitments; others argue that such a view confuses the theoretical aims of metaethics with those of a first-order theory of practical reason.

d. Familiar versus Novel

Regardless of where one stands on the issue of convergence, there is the further question of whether “global constructivism” is supposed to capture a familiar class of metaethical views or whether it is supposed to refer to a novel and as-of-yet unexplored alternative to these. Some philosophers employ the term “constructivism” to capture a broad family of views, one characterized by their shared response to the Euthyphro question. While this understanding of constructivism might draw our attention to commonalities among these views that normally go unnoticed, this understanding does not offer a novel position. This arguably limits our interest in constructivism. Other philosophers employ the term “constructivism” more narrowly to capture a much more ambitious view, namely, one that counts as a free-standing alternative to existing metaethical alternatives. If they are correct, then traditional discussions in metaethics have overlooked an important position (compare Sayre McCord 1988, Railton 1996), one that is supposed to adequately explain the nature of our ethical thinking and practice while avoiding the kinds of objections that traditional views struggle with.

3. Motivation and General Argumentative Strategy

Since constructivism is often framed in opposition to the realist response to the Euthyphro question it should not be surprising that one standard way of motivating constructivism is to present it as a response to the putative failings of realism in metaethics. But how we are to understand realism or anti-realism in metaethics is itself contested. This of course complicates things. If constructivism is presented as a response to realism but the commitments of realism are themselves contested, it would appear that in beginning with realism we are not beginning with the clearest framework for understanding constructivism. Despite this complication, however, this framework can still be useful. The situation just requires that we be explicit about how we are to understand the term “realism” in this context.

a. Constructivism versus Realism

It is fairly uncontroversial to take realism in metaethics to include at least the following two conditions:

(1) Atomic ethical statements are the kind of things that may be literally true or false.

(2) At least some of them, literally construed, are true.

These conditions look promising insofar as they serve to contrast realism with two commonly recognized non-realist competitors. The first condition contrasts the view with non-cognitivism. Defenders of these views deny that ethical statements are straightforwardly or literally fact-stating; they rather claim that we use ethical language to perform some non-descriptive function or to express some non-representational state of mind. The second condition contrasts the view with an error theory. Defenders of an error theoretic account of morality accept that we use ethical language to report beliefs but claim that all of these beliefs are systematically false because ethical terms and expressions fail to refer to anything. Again, both types of views are framed in opposition to realism. Insofar as (1) and (2) achieve this contrast, they provide a helpful way of understanding realism’s commitments.

These two conditions also appear sufficient to distinguish realism from some statements of constructivism. For example, Christine Korsgaard (2003) has described constructivism in ways that look incompatible with (1). On her account, ethical concepts do not refer to facts that we may come to know and apply in deliberation; rather, they refer to practical problems that agents must solve. The details of this proposal are not completely clear, but some have argued that Korsgaard’s view does not construe moral truth literally. If this were indeed the case, the first two conditions alone would suffice for distinguishing realism from constructivism.

Even if some statements of constructivism might be ruled out by these conditions, however, others are not. In fact, part of what many take to be attractive about constructivism is that it does satisfy these two conditions. By taking on board some of the features of realism and rejecting others, constructivists claim to capture all that is attractive about realism while avoiding standard objections against it. If constructivism failed to satisfy (1) or (2), a defender of the view could not claim any such advantage; for without them there is nothing of realism to speak of. This means that we need to add some other condition(s) to our account of realism, one or another that captures the distinction that these other constructivists have in mind.

Russ Shafer-Landau has proposed the following candidate:

(3) There are moral truths that obtain independently of any preferred perspective, in the sense that the moral standards that fix the moral facts are not made true by virtue of their ratification from within any actual or hypothetical perspective. (2003: 15)

This condition is used to describe what is sometimes referred to as the stance-independence of ethical facts and properties (for coinage of this expression, see Milo 1995). This is because it makes at least some instances of moral truth independent of “any preferred perspective”, actual or hypothetical. A perspective, or standpoint, is a complex system of intentional psychological states–or stances–such as beliefs, desires, commitments, reactive attitudes, and so forth.

According to (3), even if some ethical standards come into existence because they figure as the objects of our desires, or choices, or beliefs, and so forth, there are some that exist independently of our intentional stances. Importantly, this characterization of realism still allows that some of the reasons we have may be the result of choices and agreements we have made. For instance, it seems plausible to think that one can come to have special reasons to do things in virtue of the promises one makes and the specific intentions that this promise-making involves, reasons that one would fail to have in the absence of such promise-making. The realist can allow for this. However, she will insist that not all of the reasons one has are like this; importantly, there are also some we have independently of any of the desires, choices, or beliefs we have or the choices or agreements we have made. For example, she may insist that our reason to uphold the practice of promise-keeping in general is just such a stance-independent reason. In other words, while our reason to make good on a particular promise may depend on our having made this promise in the first place and the specific intentions that this involves, our reason to keep promises more generally would not depend on our having promised to do anything; rather, it is a reason we have that is independent of our attitudes or any perspective or standpoint which they might combine to form. We will soon have occasion to say more about what a perspective or standpoint is. For now, however, it is just important to note how this third condition serves to contrast realism with constructivism.

Unlike the first two conditions, this one does appear to get at the distinction many constructivists have in mind. Specifically, it would appear to give some substance to the intuitive sense of dependence implicit in the Euthyphro questions stated earlier. These questions suggest that constructivism differs from realism insofar as it makes ethical facts and properties depend on our ethical practice in some essential way.

If we accept that realism offers a stance-independent view of ethical facts and properties, constructivism ought to be understood by contrast as a species of a stance-dependent view. On this account, there are no moral, or ethical, truths that obtain entirely independently of any actual or hypothetical perspective. The standards that fix the relevant class of ethical facts are always made true by virtue of their ratification from within some actual or hypothetical perspective. Constructivists offer various characterizations of the relevant status-conferring perspective or standpoint as well as of the kind of ratification that is required. Some of these differences are discussed above in section 2.

Many constructivists accept (1) and (2), but argue that realists go too far in positing (3). This condition constitutes, in large part, the realist notion of ethical objectivity . For this reason, we might take constructivists to be rejecting the idea that ethical facts and properties are objective in the realist’s sense–while leaving open the possibility that they might count as objective in some other sense. Constructivists argue that by incorporating (3) realists fail to accommodate deeply held philosophical and ethical commitments. These failings fall under two broad categories.

b. Metaphysical and Epistemological Objections to Realism

The first supposed failing is that realism cannot accommodate our broader metaphysical and epistemological commitments. Here the concern is generally that realism about value, or morality, or reasons is incompatible with philosophical naturalism. Very roughly, this is the ontological thesis that the only kinds of facts and properties that exist are natural ones—that is, those facts and properties that (could) figure as the objects of investigation of our best scientific practices. The alleged problem is that ethical facts and properties could only satisfy condition (3) if naturalism were false.

There are two (related) versions of this argument in the literature. For example, according to one popular version of the objection made famous by J.L. Mackie (1977), ethical facts and properties exhibit certain necessary connections with our motivational capacities. This view is sometimes referred to as motivational internalism. If these motivational connections are understood naturalistically (for example, as connections between ethical judgments and an agent’s desires or dispositions to choose), it is hard to see how ethical facts and properties could enjoy the independence described in condition (3). They would have to be stance-independent by nature yet necessarily connected with certain motivational stances. The worry is that this would suggest, in the words of Mackie, that ethical facts and properties were “utterly different from anything else in the universe” (1977: 38). The conclusion here is that realism commits one to a kind of metaphysical queerness.

Mackie’s allegation of metaphysical queerness gives rise to a related concern about epistemological queerness. If ethical facts and properties are metaphysically different from anything else in the universe, why should we think that we could discover them in the same way we come to know natural facts and properties (that is, via observation and empirical theorizing)? Here the particular worry is that we could only come to know them via some mysterious faculty of intuition. Hence a queer metaphysics would require a queer epistemology.

While Mackie was the first to present these objections, there are also more recent versions of this kind of naturalistic argument–ones that respond to Mackie’s worries about queerness with a constructivist solution. For example, Street (2006) claims that realism is incompatible with our best evolutionary account of how we came to make the ethical judgments we do. According to this argument, if realism were true we would have no good explanation of how our ethical judgments have succeeded in matching (or “tracking”) stance-independent ethical truths; rather, the truth of these judgments would have to be entirely a matter of unlikely coincidence.

Constructivism, by contrast, is supposed to avoid these problems. By grounding ethical truths in features of intentional states, constructivists claim that their view makes use of only naturalistic materials, ones that can be accounted for by empirical psychology. These are features that may be appealed to in order to explain the apparent connection between ethical judgments and motivation. They might also help the constructivist avoid Street’s skeptical scenario. This is because the constructivist will argue that there is no serious gap between ethical judgment and truth that the skeptic may exploit.

Of course, these types of naturalistic concern alone do little to distinguish the constructivist challenge from others, such as the challenge error-theorists and expressivists mount against realism. In fact, it would appear as if every major challenge to realism incorporates some version of this worry. But this is not the only motivation to which constructivists appeal. This first type of concern is usually coupled with a second type.

c. Objections to Realism from within Ethical Theory

The second type of objection concerns realism’s failure to accommodate purportedly deep features of our first-order ethical thinking. These include many people’s commitment to the idea that there is a necessary connection between moral or evaluative judgments and reasons for action as well as the idea that autonomy is an essential and ineliminable aspect of our practical thinking. Unlike the first type of objection, which appeals to one’s broader philosophical commitments in metaphysics and epistemology, this objection comes from within ethical theory itself.

Many moral philosophers maintain, or are at least attracted to, a view called moral rationalism. According to this view an action’s rightness necessarily provides some reason to perform it; alternatively, an object’s or state-of-affair’s goodness necessarily provides some reason to pursue or promote it. These kinds of considerations arguably come from within first-order ethical theory, since the relata (rightness or goodness, on the one hand; reasons for action, on the other) are the proper objects of first-order ethical investigation.

Although rationalism per se is not incompatible with ethical realism–indeed defenders of a robust form of non-naturalist ethical realism also accept something like this view, it does pose problems for realism when it is combined with a non-realist account of practical reason. That is, in order to secure a non-realist conclusion, constructivists must combine an appeal to rationalism with a rejection of realism about practical reason. On this view, moral facts about rightness or evaluative facts about goodness necessarily entail certain reasons for action, but these reasons are not to be understood as objective, stance-independent facts that we come to know through ethical inquiry; rather, these reasons are determined (that is, “constructed”) by agents engaged in the activity of practical reasoning. For an example of this kind of view see Korsgaard (1996).

This rejection of realism about practical reasons together with a commitment to rationalism puts pressure on one to accept a stance-dependent account of morality and value, as well. For it is difficult to see why there should be a necessary connection between such different types of things (compare Shafer-Landau 2003: 48-49). Why should one think that the realist’s objective, stance-independent moral or evaluative facts necessarily correlate with the results of the stance-dependent outcomes of practical reasoning?

The constructivist rejection of realism about practical reason in turn either rests on an appeal to broader metaphysical or epistemological commitments, like naturalism (which the aforementioned realists reject), or other deeply entrenched first-order ethical convictions, like the importance of autonomy for rational agency (which arguably a realist should also be concerned to preserve).

As with the argument from rationalism, the argument from autonomy again appeals to a commonly-held commitment within ethical theory. The claim in this case is that autonomy is an essential and ineliminable feature of practical agency and that such autonomy requires a kind of control that is at odds with a realist account of practical reason (Korsgaard 1996). According to this argument, autonomous practical agency involves self-legislation–in the sense that practical agents are both the authors of the content of practical laws and the authors of their own obligation to uphold these laws. Constructivism in metaethics is supposed to be fully compatible with such a view of autonomous practical agency. But if a robust, stance-independent realism were true, we could not be said to legislate the content of practical laws or our own obligation to uphold these laws. Therefore, autonomy favors thinking that constructivism in metaethics is correct and that realism is mistaken. For criticism of this argument, see Shafer-Landau (2003) and Robert Stern (2012).

Defenders of constructivism disagree about which of these considerations (naturalism or rationalism or autonomy) poses the strongest challenge to realism. However, as these brief remarks here already illustrate, the arguments they advance conform to a general strategy: first, there is an appeal to one or another of these considerations; second, realism is presented as failing to adequately account for this particular consideration; finally, constructivism is presented as possessing of superior resources for explaining it. In short, the constructivist claims a series of explanatory advantages over realism. Although one might reject one or another of the constructivist’s arguments, the constructivist contends that her view wins out on holistic grounds. Even if realism can accommodate some of these considerations to some extent, the constructivist argues that her view does a better job on the whole. In other words, the constructivist claims to get you everything the realist wants (and more) without any of the problems that realism supposedly introduces.

4. Is Constructivism “Free-Standing”?

Regardless of whether constructivism succeeds in the above arguments, one might still worry that “constructivism” is merely a new label for another well-established view, one whose virtues and defects have already received much attention. Here we return to one of the issues about scope that we encountered earlier. One traditional worry is that much of what has been said thus far about constructivism appears as if it applies to a family of views that are sometimes referred to as response-dependence theories. Subsequently, both constructivists and non-constructivists alike have questioned constructivism’s cognitivist credentials and pressed for details as to how such a view might contrast with expressivism. Furthermore, one might worry that constructivists only succeed at distinguishing their view from expressivism or response-dependence theories to the extent that they construe it as a form of simple subjectivism, a naturalistically reductive view that makes ethical facts or properties a function of an agent’s desires. How is ethical constructivism different from such views? Is constructivism a distinct alternative to response-dependence theories, expressivism, and simple subjectivism? Or does it perhaps represent a species of one of them? Alternatively, might we take constructivism to be the family or genus under which these other views fall?

If constructivism merely turned out to be a version of one of these other views (either species or genus), this would arguably detract from its importance. Part of what is supposed to make the constructivist challenge to realism an interesting one is that it has not received the attention it deserves. This would arguably not be true if it turned out to be a version of a response-dependence theory, or expressivism, or simple subjectivism. Although questions remain as to how we are best to understand the commitments of these other views, they have each commanded a lot of discussion already. In light of this, the strengths and vulnerabilities of each type of view are fairly well established. Moreover, it is difficult to see how constructivism might serve as an improvement on any of these familiar positions–since some of the most compelling objections to each, respectively, are general enough that they would appear to extend to any of their species, constructivist or otherwise. The Frege-Geach problem for expressivism and extensional worries about response-dependence theories (each discussed below) are arguably examples of this. For this reason, it is important to sketch out a sense in which constructivism might count as a free-standing metaethical alternative to these views–that is, a sense in which constructivism counts as a genuinely novel metaethical position and not just another way of describing a more familiar view.

a. The Proceduralist Characterization

Perhaps due to the influence of Rawls, constructivism has typically been understood as the view that ethical truth is determined by the outcomes of procedures. The proceduralist characterization of constructivism has been accepted both by advocates like Milo (1995), Korsgaard (1996) and Street (2008) and by critics like Darwall et al. (1992), Enoch (2009), Ridge (2012) and Copp (2013).

This has led many to doubt whether constructivism represents a free-standing metaethical position. A proceduralist characterization of constructivism easily lends itself to formulation in terms of a familiar family of stance-dependent views in metaethics: response-dependence theories. As such, constructivism would appear to represent a species of such views and, consequently, be subject to the same objections.

Response-dependent views have been described in different ways. Some have defended a response-dependence view of ethical properties. We might take such views to provide the following schematic account of the essence of ethical properties (compare Johnston 1989):

x is C iff (and because) x is such as to produce R in Ss under conditions K

Here C stands in for some ethical property (for example, the property of goodness, wrongness, being a reason), S the subject, K the relevant conditions, and R the response. In order for this equation to pick out a response-dependent property, there are other conditions that must also obtain. For example, the biconditional cannot obtain trivially in virtue of S, K, and R specifying a “whatever it takes” condition. But, side stepping the controversies involved in specifying such conditions, it is already apparent why one might take constructivism to represent a species of such views. The proceduralist characterization lends itself to formulation in terms of subjects, responses, and conditions. For example, Rawls’s statement of a constructivist view of justice might be made to fit the response-dependence schema in the following way.

A policy/institution, x, is just iff (and because) x conforms to principles that would be agreed to by free and equal citizens under the conditions represented in the original position.

Here, C is the property of justness. R is the disposition to produce agreement, a volitional response. S is a free and equal citizen of a society. K is the conditions described in the original position. There may be renderings of Kantian constructivism about justice that better capture Rawls’s view. The point here is just to illustrate how a view that focuses on procedures lends itself to an interpretation in response-dependence terms. In fact Rawls’s statement of constructivism is not unique. The constructivist proposals of T.M. Scanlon and Christine Korsgaard would also appear amenable to a response-dependence formulation.

But if ethical constructivism is best understood as a response-dependence view, as these examples suggest, it would not represent a free-standing metaethical view. Furthermore, it would appear to be subject to the same objections that have been levelled against these views. Different philosophers have recognized a dilemma for response-dependence theories (Blackburn 1993; Darwall et al. 1992), as follows.

We may understand a response-dependence account as providing either a non-reductive or a reductive account of some class of ethical properties. If it is non-reductive (that is, it includes some ethical terms on the right-hand side of the equation), the account will leave traditional metaethical questions unresolved. Specifically, it will not tell us how we are to understand the ethical terms employed in the account, leaving open the possibility that they may take a realist, or expressivist, or error-theoretic, and so forth, interpretation. If it is reductive (that is, it includes no ethical terms on the right-hand side), the account runs the risk of being extensionally inadequate. In other words, the account cannot guarantee that the outcomes will match our considered ethical convictions. In the case of constructivism, this might be expressed as the worry that the subjects of the relevant procedures, actual or hypothetical, might get things wrong. A second related worry concerns the intensional adequacy of such views. Here the objection is that reductive accounts would make the ethical facts “hostage to the outcome of irrelevant causal processes” (Street 2010: 374), irrelevant because our ethical judgments themselves might not appear to be about such agents and their judgments.

A defender of the proceduralist characterization might argue that constructivism provides some new way of navigating around this dilemma. But it difficult to see how it could. The features of a response-dependence view that make it vulnerable to the dilemma are general and appear, as such, to apply equally to a proceduralist interpretation of constructivism.

A more promising response, perhaps, would be for the constructivist to accept one of the horns but argue that the associated objection is not as bad as one might think. But this type of response is also available to defenders of response-dependence views more generally. It still would not provide us with any reason for thinking that constructivism was a free-standing metaethical view; rather, it would appear as if constructivism and response-dependence theories (in general) stand or fall together. If constructivism is to represent a free-standing view it cannot be construed in terms of procedures. This has led defenders of the view to reject the proceduralist characterization and emphasize the ways in which constructivism differs from response-dependence theories.

b. The Standpoint Characterization

Sharon Street (2010) has argued that constructivism is best understood as a distinct and superior alternative to response-dependence views in metaethics. She describes metaethical constructivism as the view that

…the truth of a normative claim consists in that claim’s being entailed from within the practical point of view, where the practical point of view is given a formal characterization. (2010: 369)

Street’s account explicitly avoids any characterization of constructivism in terms of procedures. Again, if constructivism specifies a procedure, this leaves the view open to the dilemma just sketched. From this one might infer that the solution is to avoid talk of procedures (compare also James 2007). So the constructivist retreats from talk of procedural outcomes to what is alleged to be the less problematic, talk of points of view, or standpoints.

Street illustrates the difference by appeal to an example about baseball and how response-dependence and constructivist views would differ in their response to the question What is it for Jeter to be safe? Whereas the former would state the conditions for Jeter’s being safe (a normative fact in baseball) in terms of the responses of an umpire (a good umpire would judge him to be safe), the latter states the conditions in terms of what would be entailed by the rules of baseball in combination with the non-normative facts. Street argues that this formally-construed constructivist alternative is immune to the standard objections that befall reductive response-dependence accounts. On the one hand, it yields the right results; it is extensionally adequate. Unlike the response-dependence view it leaves no room for errors of judgment. On the other, it would appear to capture the sense of what it is for Jeter to be safe. That is to say, it is also, on Street’s view, intensionally adequate.

But what is a standpoint? Although many philosophers appeal to standpoints (especially those working in the Kantian tradition), there is very little detailed discussion of what they are. For example, Street describes the practical point of view as

…the point of view occupied by any creature who takes at least some things in the world to be good or bad, better or worse, required or optional, worthy or worthless, and so on–the standpoint of a being who judges, whether at a reflective or unreflective level that some things call for, demand, or provide reasons for others. (2010: 366)

This description presupposes that we already start out with some sense of what such a standpoint is. Other descriptions of standpoints appeal to metaphor or invoke a distinction between the practical and the theoretical, each of which is supposed to represent a distinct and familiar way of experiencing the world (Wallace 2008).

Let us assume that a standpoint is constituted by a complex system of stances (that is, psychological states that we bear towards things and that, in virtue of being directed towards these things, have a kind of content) such as beliefs, desires, commitments, reactive attitudes, and so forth. In other words, it is a set of individual stances that hang together in a certain way. This much would appear safe if we are correct in understanding the distinction between realism and constructivism in terms of stance-dependence. But if we are to avoid the response-dependence dilemma, it is important that these stances not be described as issuing from any particular type of subject under specific conditions. One alternative would be to focus on the kinds of activities associated with various practical standpoints. Here the idea is that we first look to those familiar activities of, for example, valuing, taking something to be wrong, taking something to be a reason for acting, in order to identify the relevant practical standpoint and then ask what it is to engage in these activities as such.

Korsgaard (2003), James (2007) and Street (2010) describe the constructivist project as one of working out the “constitutive commitments” of various practical standpoints. This involves, amongst other things, the task of specifying the various ways in which particular types of stances must hang together so that one may count as genuinely engaging in a particular practical activity as such.

For example, stances can presumably either support or conflict with one another. Conflicting stances are ones that are in some sense inconsistent with each other. Although Katie may consistently take herself to have both some reason to attend the concert and some reason not to, she may not consistently take herself to have both an all-things-considered reason to attend and an all-things-considered reason not to. Someone who simultaneously maintains these stances arguably fails to meet the basic requirements for taking something to be an all-things-considered reason for acting. This kind of conflict illustrates perhaps the most straightforward sense in which practical stances may count as inconsistent. But there are other ways, too.

Consider someone who takes herself to have an all-things-considered reason to save her life, believes that in order to do so it is necessary that she see a doctor immediately, but takes herself to have no reason whatsoever to see a doctor (compare Street 2008: 227-228). These stances are also in some sense inconsistent with one another. As in the earlier example, someone who simultaneously maintains these stances arguably fails to meet the basic requirements for taking something to be an all-things-considered reason for acting.

A standpoint constructivist might claim that this is because the activity of taking-something-to-be-a-reason-for-acting as such is in part constituted by a norm of instrumental consistency, one that requires that one take oneself to have at least some reason to take the necessary means to one’s ends. As both Street and Korsgaard point out, someone who fails in these ways is not making a mistake about what her reasons are; rather, she does not genuinely count as taking herself to have an all-things-considered reason at all. But consistency is not the only kind of relation that one might take to matter.

Those stances that do not conflict may stand in various degrees of support to each other. Among a set of mutually consistent stances, some will be more central to a particular standpoint, others more peripheral. The extent to which stances on balance exhibit support of one another is a measure of their coherence. By comparison with consistency, it is more difficult to say how coherence might figure as a constitutive requirement for a particular standpoint. Presumably, one either does or does not count as occupying a standpoint; it is an all or nothing affair. But coherence comes in degrees. Surely one may count as genuinely engaging various practical standpoints even if the relations amongst one’s set of stances falls short of maximal coherence. But what if they fell short of minimal coherence?

Coherence might figure as a threshold requirement. Consider someone who is deliberating about whether to attend a party. She considers who will be there, whether there will be dancing, how she will feel the next morning, how this might affect her work schedule, and so forth. After much reflection she concludes “I have an all-things-considered reason to book a flight to Tokyo!” Although there is nothing apparently inconsistent with her taking up this stance, it does not mesh in any way (let us assume) with the considerations she has been entertaining. It fails to cohere with them in any obvious way. Someone who takes up this stance in the present situation arguably fails to count as taking herself to have an all-things-considered reason. Here we might say that the relation this stance bears to the background of the agent’s other stances exhibits a degree of coherence that falls below the threshold that is constitutively required to be counted as engaging in the activity as such.

Coherence might not be the only relation that matters in this way. There may turn out to be different constitutive norms whose satisfaction contributes to a standpoint’s overall coherence. Part of the constructivist project will involve describing what other types of norms or relations are constitutive of various practical standpoints. For example, James (2007) has claimed that the standpoint of practical reason is constituted by certain general norms which determine, among other things, which facts one should attend to in deliberation (a “norm of attention direction”), which to disregard (a “norm of disregard”), which to count as favoring a particular response (a “norm of favoring”), and which to assign more or less importance (a “norm of balancing”). Like the norm of coherence, but unlike the norm of instrumental consistency, these norms would also appear to allow satisfaction to various degrees.

Once the constructivist has an account of these various constitutive commitments in hand, she can then appeal to them to explain the truth or falsity of a particular ethical judgment. According to the standpoint characterization of constructivism, the truth of an ethical judgment is a function of what follows from within a particular practical standpoint. In other words, the truth of a particular ethical judgment is always to be understood as relative to the various relations and norms that constitute a particular practical standpoint. Given a particular collection of stances and the norms governing a particular standpoint, certain stances will follow, others will be ruled out, and still others will enjoy some degree of support but fall short of being “entailed” from within a particular ethical standpoint. This brief sketch leaves many questions unanswered. But it should already allow us to see how constructivists, like Street, might appeal to a standpoint characterization to distinguish their views from the family of response-dependence theories.

Importantly, our judgments about a particular practical standpoint are not about how some subject–actual or hypothetical–would respond; nor are they about how such agents ought to respond. The dilemma for response-dependence views is a result of the way in which these views describe ethical truths indirectly. On these views, the truth of an ethical judgment is described in terms of how some “suitably represented” agent would respond. This allows for a gap between our intuitive ethical judgments and our judgments about how such agents would respond. On the one hand, the agent could get things wrong; on the other, our ethical judgments themselves (the direct ones) might not appear to be about such agents and their judgments. The move to standpoints is supposed to close this gap.

According to the standpoint characterization of constructivism, an ethical judgment is not about what some suitably represented agent would judge or choose. Rather, it is about what follows from within a particular ethical standpoint. In contrast with response-dependence views, the standpoint does not represent an agent. Hence, there is no one who could get things wrong. Moreover, such a standpoint does not reduce ethical judgments to anything else; this is supposed to make it immune to “open question” worries about the account’s intensional adequacy.

One might worry that the extent to which the standpoint characterization succeeds in distinguishing constructivism from response-dependence views is also the extent to which the view starts to look like other existing metaethical alternatives: realism, expressivism, or a simple subjectivism. Suppose that what distinguishes constructivism from response-dependence views is that on the former view ethical judgments are about what follows from within a particular standpoint and not how a certain type of subject would respond under suitable conditions. If this is the case, it is clear how constructivism might count as a version of cognitivism. Ethical judgments are a species of belief, ones that report facts about what follows from within a particular ethical standpoint. But how are we to understand the nature of the “primitive” stances that make up these standpoints? So far, all that we have been told is that they are not about a suitably represented subject’s responses.

c. Ridge’s Argument by Elimination

Michael Ridge (2012) presents a serious challenge to recent efforts to find a plausible, novel, and free-standing version of constructivism in metaethics–one that is especially troublesome for defenders of the standpoint characterization. His argument is one that proceeds by elimination. Ridge exhaustively lists the various ways in which we might understand an agent’s primitive ethical stances and then argues that the forms of constructivism each generates fail to constitute a novel or free-standing alternative to familiar metaethical positions. Ridge counts five options. Due to restrictions of space, however, the following presentation takes a more schematic approach.

According to the standpoint view, ethical judgments are two-tiered. At the second tier, ethical judgments express beliefs about what follows from within a particular ethical standpoint. But how are we to understand the “primitive” first tier judgments or stances–the ones that make up a standpoint? What are they? Do they have their own representational content or are they non-representational states of mind? These questions are crucial for determining whether constructivism represents a free-standing view. Yet it is not clear that the standpoint constructivist can answer them in a way that succeeds in distinguishing her view from familiar alternatives.

Suppose that the first-tier stances are a species of belief. That is, they have representational content. What do these first-tier stances purportedly represent? There would only appear to be two options. Either they represent features of the world that are independent of these beliefs, or they represent one’s other first-tier beliefs. But neither of these options is a promising way of establishing constructivism as a free-standing metaethical position.

On the one hand, if the first-tier beliefs represent features of the world that obtain independently of our stances (that is, stance-independent ethical facts), the view just turns out to be a version of realism. For, in this case, there are at least some ethical judgments whose truth does not ultimately depend on the relations they bear to other stances within a particular ethical standpoint; rather, some will ultimately depend on the relation they bear to the world. On the other hand, if they represent one or another of the other first-tier beliefs that constitute the standpoint, the view may avoid realism. But, in this case, the worry is that this makes the view either vacuous or objectionably circular.

So far, we have been supposing that the first-tier stances are something like beliefs. But, what if they have some kind of non-representational content, how do we understand the states of mind that these basic ethical stances embody?

Suppose that the first-tier stances embody some non-representational state of mind. Considering some of the motivations to which constructivists appeal, one might assume that these basic stances embody a form of pro-attitude, like desires. But if one is able to work out the constitutive relations amongst this class of non-representational pro-attitudes, one will have arguably succeeded in one of the projects central to expressivism.

One of the big challenges for expressivists, the so-called “Frege-Geach problem”, is to explain how ethical discourse exhibits standard logical inference patterns despite the fact that ethical language is not fact-stating, on their view. Standard logical inference is truth preserving. But expressivists do not think that ethical language is used to express truth-evaluable content. So expressivists must come up with an alternative “practical logic” which shows that it is nonetheless legitimate to use ethical language in these ways. Expressivists have offered different proposals, but they remain extremely controversial.

Constructivism is usually understood as a version of cognitivism. This is because it makes ethical judgment, at some level, a species of belief. In particular, the standpoint constructivist understands the second-tier ethical stances this way. They are beliefs about what follows from within the various practical standpoints. They have truth-evaluable content and, as such, should figure unproblematically in contexts which require such content (belief reports, truth-preserving inferences, and so forth). This might create the impression that constructivism will be immune to the kinds of objections that expressivists face. But if the stances that constitute these standpoints are themselves non-representational, it would appear that constructivism is saddled with the same project as expressivism, at least at the level of the first-tier ethical stances.

If certain non-representational stances are supposed to follow from within a particular standpoint constituted by other non-representational stances, we must suppose that the relations amongst these stances constitute a structure with its own non-truth-preserving “practical logic” (compare Gibbard 1997). It is only once this logic is worked out that a constructivist will be able to say whether a particular second-order stance–in this case a belief–is true or not. If this is indeed the way to understand the standpoint constructivist’s apparatus, one might object that the view does no better, or even perhaps worse than expressivism. In fact, an expressivist might argue that the constructivist ought to avoid the complication of an additional tier of judgments and simply abandon cognitivism altogether; instead, she should take ethical statements to directly express the non-representational states of mind that constitute the various ethical standpoints. This would in effect make the view a species of expressivism.

This is a line that become increasing popular in the early 21st century. Several defenders of expressivism have argued that constructivism is best understood as a species of, or supplement to, their view–see Gibbard (1997), Lenman (2010), Ridge (2012). It has even been encouraged by some constructivists–including Korsgaard (2003) and, to a lesser extent, Street (2008, 2010).

But if constructivism is indeed best understood this way it arguably loses in importance as a challenger to realism. The expressivist challenge to realism is both familiar and fairly well understood. Moreover, a constructivist-expressivism would arguably present a weaker challenge than the existing “quasi-realist” versions advanced by expressivists like Blackburn. Not only would a defender of constructivist-expressivism be giving up on cognitivism, she would also be giving up on even the appearance that ethical discourse is stance-independent. Quasi-realist expressivists are at least concerned to accommodate realist ways of talking and thinking about objectivity in ethics. Recall that one of the motivations for constructivism is that the view is purportedly able to secure everything the realist wants without the problems that realism allegedly introduces. But someone who defends this kind of constructivism arguably fails to secure anything the realist wants. Although such a view might represent an interesting internal challenge for expressivists, it would not appear to present a novel or especially plausible challenge to realism. But the only apparent way around this objection risks making constructivism into a version of another well-known metaethical position.

Any version of constructivism that characterizes ethical standpoints in terms of non-representational stances will have a problem distinguishing itself as a free-standing view. In order to see why, let us suppose that the constructivist denies that an ethical standpoint involves a level of structure that would require a practical logic. This would position the view closer to a simple form of subjectivism– for example, a view that takes moral judgments to express beliefs about which acts would maximally satisfy an agent’s actual desires. In this case, one might also describe this form of subjectivism as providing a two-tiered account of ethical judgments. At the first-tier there are desires, a kind of non-representational stance; at the second-tier there are beliefs about these desires. Furthermore, one might argue that such a view, like a standpoint constructivism, is distinct from the family of response-dependence theories.

According to simple subjectivism, ethical judgment is not about how certain subjects would respond; rather, it is about whether an action satisfies one’s actual desires, and how many or, alternatively, how strong these are. Importantly, however, the subjectivist does not take the second-tier judgments to be about what follows amongst an agent’s desires; rather, they express beliefs about how many desires on balance would be satisfied, or frustrated, by a particular course of action. Such a view arguably does not require any logic. Although an agent’s set of desires may exhibit some structure–for example, with some desires taking other desires as their objects, or some desires being more general and others specifications of them–it does not involve a level of sophistication that would support “entailment” claims. Consequently, the challenges associated with expressivism do not arise.

Simple subjectivism provides a model for how a constructivist might avoid the kind of difficulties associated with the expressivist’s project. Of course, the problem with this approach is that it requires that the constructivist explain how her view represents a novel and interesting advance on common versions of simple subjectivism. One might have thought that the extent to which constructivism represents an improvement on such theories is the extent to which the view incorporates structure at the level of first-tier ethical stances (compare Street 2008: 230-1).

There would appear to be a dilemma for a constructivist who insists that first-tier stances are non-representational. Either these stances combine to create a structure within which some stances may be said to follow from others, in which case the view involves the same difficulties that expressivism does. Or a standpoint is to be understood as a mere collection of stances without any sophisticated structure, in which case the view starts to look like a version of simple subjectivism, with all the virtues and vices that such views carry.

The prospect of a freestanding metaethical constructivism is looking dim. The standard proceduralist characterizations give the appearance that constructivism is best understood as a version of a response-dependence theory. This might make the standpoint characterization appear more promising. But if an ethical standpoint is constituted by beliefs, constructivism either folds into realism or turns out to be vacuous. If it is constituted by non-representational stances, it is best interpreted as a species of, or supplement to, expressivism or a version of a simple subjectivism. Unless constructivism can be shown to represent an advance on one of these alternatives, the view would appear to lack in motivation. Nothing that has been said thus far rules out this possibility. But even if constructivism represented an improvement on response-dependence theories or expressivism or simple subjectivism, it may still fail to represent any new or interesting challenge to realism. One would have to show that constructivism improves on these other views in ways that also make for a more formidable challenge to realism. Perhaps the more promising option would be to give up on the claim that constructivism represents a free-standing metaethical view and argue that the challenge presented by constructivism is of a different sort.

5. A Challenge to Traditional Metaethics

One such recent proposal locates what is novel and important about the constructivist challenge in the Kantian distinction between practical and theoretical reason. Defenders of this interpretation of constructivism in metaethics include Christine Korsgaard (2003), Stephen Engstrom (2013), and Carla Bagnoli (2013). They argue that traditional approaches in metaethics understand practical reasoning as a kind of “applied” theoretical reasoning but that this fails to appreciate the distinctively practical nature of deliberation and choice.

Traditional debates in metaethics typically recognize a number of platitudes about the nature of moral discourse and experience. Two of the most prominent of these include the common ideas (i) that there are correct answers to normative questions and that these correct answers are made correct by objective normative facts and (ii) that our judgments about the correct answers to normative questions are themselves sufficient to motivate us to act under normal circumstances (Smith 1994: 6-7).

However, traditional approaches in metaethics have struggled to adequately account for both of these features in a non-mysterious way. This, again, is the problem of “queerness” that Mackie identified and that we have discussed above in section 3b. As a result, we find some traditional views in metaethics that emphasize the objectivity of ethics but sacrifice or downplay the connection between normative judgment and motivation; others emphasize the motivational connection but sacrifice or downplay the objectivity of ethics.

The proposed constructivist response to this dilemma involves rejecting the underlying understanding of practical reasoning as a kind of “applied” theoretical reasoning, together with its “ontological” conception of objectivity in ethics. Theoretical reasoning attempts to acquire knowledge of facts that exist prior to and independent of its activity. It is the independent existence of these facts that makes theoretical reasoning objective. Bagnoli describes this as an ontological conception of objectivity because objectivity here depends on the existence of a special class of facts. But she and other constructivist critics argue that the same feature which constitutes the objectivity of theoretical reasoning also makes this kind of objectivity unsuitable for practical reasoning. For practical reasoning is ultimately concerned with deliberation and action; its verdicts carry a special authority that has the force, under normal conditions, to move us to act.

According to the constructivist critique, traditional approaches in metaethics conceive of practical reasoning as an attempt to gain theoretical knowledge of prior and independent normative facts and then apply this knowledge in deliberation. But it is precisely this theoretical conception of objectivity as “external” that would appear to be at odds with the “internal” authority and motivational power of practical judgments. It is difficult to see why an ontology of prior and independent normative facts should generate reasons that are authoritative and efficacious from within the practical standpoint of someone deciding what to do. As Korsgaard (1996, 2003) argues, one can always ask why one has reason to do what the prior and independent normative facts indicate that one should do. If this is the case, one might think that the underlying account of practical reason has failed to do its job.

In contrast to the ontological conception of objectivity, Korsgaard, Engstrom, and Bagnoli each argue in their own way for a “practical” conception of objectivity in ethics. They agree that a successful account of practical reason will be one that explains the normative authority and motivational force of practical judgments in terms of the special objectivity that is constitutive of the activity of practical reasoning itself. These constructivists follow Kant in characterizing ethical objectivity in terms of the constitutive conditions of rational agency and the specific form of practical reasoning that this involves. According to the kind of Kantian constructivism they advance, practical reasoning is an activity with its own internal constraints. In particular, it is an autonomous form of activity. This means that it is both an activity that must be objective and one whose objectivity cannot come from an external source (compare Kant 1998).

This is where the constructivist interpretation of autonomy as a form of self-legislation comes into play. On this view, one is subject only to those laws that one has legislated oneself. As laws the results of self-legislation must take a special universal form that constitutes their objectivity. As self-legislated these laws are not external to one’s own practical reasoning and hence are able to provide a source of practical authority. In deciding what to do, one is at once aware of oneself as both the author and the subject of the normative demands on which one acts.

Some claim that this conception of practical objectivity succeeds where the ontological conception fails: namely, that it is able to ground the normative authority and motivational efficacy of practical judgments. The idea is that in order to be a rational agent one must act on certain kinds of universal principles or reasons. Strictly speaking, failure to act on these principles or reasons does not mean that one acts badly; rather, it means that one fails to be a rational agent or act at all. Hence, insofar as one is to count as a rational agent or act all, one must necessarily take these principles or reasons as decisive.

Does this account of practical objectivity also succeed in establishing constructivism as a genuinely novel and free-standing alternative to traditional approaches in metaethics? It is not clear. Although this form of Kantian constructivism does appear to establish an important distinction between constructivist and traditional understandings of practical reason, one might argue that these claims about the relation between objectivity and practical authority nonetheless belong to a first-order inquiry into the demands of practical reason (Hussain and Shah 2006). If this is the case, both realists and expressivists may plausibly argue that they are able to help themselves to the same resources that constructivists have developed. Moreover, by shifting the focus of metaethical debates away from traditional semantic and metaphysical concerns, one might object that these constructivists have merely changed the subject.

6. References and Further Reading

a. Classical Statements of Constructivism

- Darwall, Stephen and Gibbard, Allan and Railton, Peter. 1992. “Toward a Fin de siecle Ethics: Some Trends.” Philosophical Review 101: 115-189.